The Rise of The New Yorker

From Hell’s Kitchen to Midtown

That piece is worth coming back to work for. It will turn out to be a memorable one, or I am a fish.

—Harold Ross

The New Yorker and the Algonquin Round Table go together like gin and tonic. Without the Vicious Circle, the magazine wouldn’t exist today. Its early success came because founding editor Harold Ross, a virtual unknown when he landed in New York in 1919, had personal relationships with the Round Table members. Described as a “genius in disguise,” Ross was a master manipulator and wildly successful at turning personal relationships into material for his magazine.

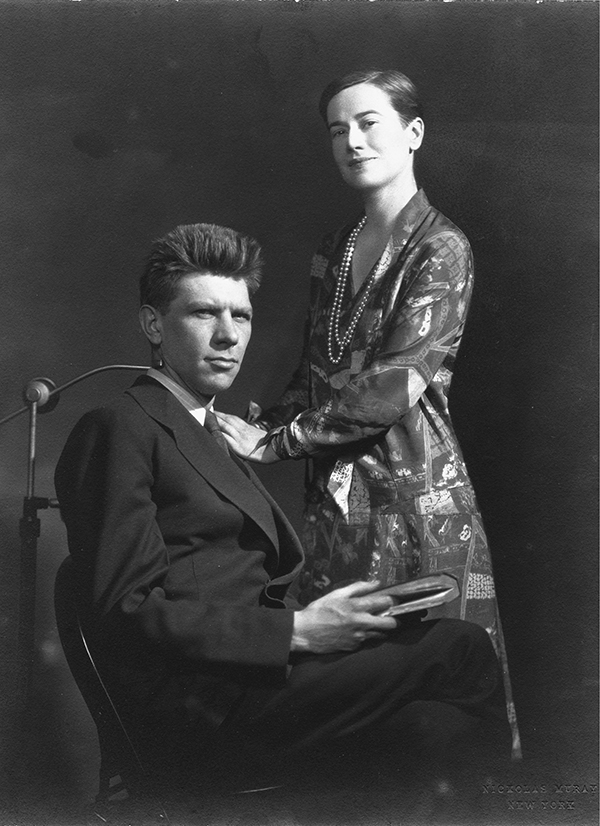

At age twenty-five, Ross joined the army in San Francisco, and he might have returned there after the war. But after befriending New Yorkers in Paris, such as Franklin P. Adams and Alexander Woollcott, the idea of continuing his career in Manhattan appealed to him. The real draw, though, was Jane Grant, with whom Ross had fallen deeply in love in Paris. He followed her back to New York, and they married two years after the war. When he returned to civilian life, Ross abandoned newspapers and took up magazine editing, which paid the bills while he planned bigger things. Grant pushed, energized, and encouraged Ross to pursue their dream of publishing a magazine. As she said after his death, “Ross had not yet been bitten by ambition.”

The New Yorker was dreamed up in Hell’s Kitchen and launched in office space within spitting distance of the Algonquin Hotel. For nine decades its impact on the city and the nation has been profound. These are the locations of The New Yorker.

1. Home of Harold Ross, Jane Grant, Alexander Woollcott

No place is more important to the launch of The New Yorker than 412 West 47th Street, where Jane Grant and Harold Ross cooked up the magazine in their second-floor bedroom in 1924. The couple married in early 1920 but didn’t immediately move in together. Strapped for funds, Heywood Broun and Ruth Hale took the newlyweds in for a summer, and the odd couple briefly took a suite at the Algonquin. Their first apartment was a walk-up they rented for two years at 231 West 58th Street, near Central Park. It lay above an auto parts shop, which probably explains why Grant pushed Ross to buy something elsewhere. Grant wanted an apartment; Ross a house. They compromised, settling on a duplex in Hell’s Kitchen.

At the time, the neighborhood was still a little rough, and the house stood just west of the Ninth Avenue El. Grant didn’t want to move there: “Hell’s Kitchen was, in fact, an Irish-bordered-by-Negro slum,” she said. But the price was right: $5,000 down, and an $11,000 mortgage. She got over her prejudices. The couple undertook a massive renovation of the twin houses and drew up plans to start a cooperative, with the intention to sell shares to friends. The first taker was Alexander Woollcott; three other acquaintances became renters.

Woollcott tried to make the house his fiefdom, to no avail. ◆ ◆ ◆

At the housewarming party in 1922, the neighbors on West 47th Street got a taste of what to expect from the new tenants. Grant lined up a private bootlegger to supply the spirits. Just about every member of the Round Table along with two hundred guests attended. Charles MacArthur and Dorothy Parker helped to fund a street carrousel for the neighborhood kids, and in the living room Grant set up a roulette wheel and a table for chemin de fer.

In the coming months and years, “412” became a special house for the group. The twenty-five-foot-square community room hosted marathon poker parties and long discussions that would eventually launch The New Yorker. A communal kitchen often fed close to fifty on weekends, requiring Grant, Ross, and Woollcott to employ a staff of cooks and servants. Iron steps led to the back garden, where the group installed a fountain and patio. Chinese lanterns lit the backyard for parties.

In 1924 Ross quit the American Legion magazine he was editing. While living in the Hell’s Kitchen house, he lined up the resources to launch what became The New Yorker. While Grant worked as a reporter on the Times and sold pieces to the Saturday Evening Post, the couple salted his salary away to finance their new venture. In its early days, Ross met with editors at all hours in the house, even while he was shaving. E. B. White talked to Ross over dinner at “412,” and editorial plans were drawn up there.

Stacked in the apartment were manuscripts to read, cartoons to review, and dummies for upcoming issues. The house intertwined with the life of The New Yorker, as well as Grant and Ross. Just two years after the magazine launched in 1925, the marriage collapsed. On August 6, 1928, they permanently separated. The couple went their separate ways, and the house was sold.

In the Sixties, Grant believed “412” was haunted: “The ghost—a male figure—is said to appear mostly on the second floor back, Aleck’s old room, and later Ross’s bedroom. I hope he has as much fun there now as we did during those five years.”

2. First Office, 1925–1935

The sixteen-story building opened around 1910 and has 145,000 square feet of office space. Starrett & Van Vleck designed it. Goldwin Starrett, a founder of the firm, had designed the Algonquin Hotel. The developers were James T. Lee, grandfather of Jacqueline Kennedy, and his partner, Charles R. Fleischmann.

In 1924 Jane Grant and Harold Ross started to build the company that would create The New Yorker. Grant and Ross showed their mock-up of the first issue to potential advertisers, investors, writers, and subscribers. Ross fibbed that he had lined up “advisory editors” such as Connelly, Kaufman, Parker, and Woollcott. They landed their biggest investor, Raoul H. Fleischmann, whom Grant had met while playing bridge. Raoul Fleischmann was the scion of a wealthy family that controlled the General Baking Company, one of the country’s largest bread manufacturers. A benefit of Fleischmann’s cash was that he had access to free office space one block from the Algonquin. One of his older brothers was an owner of 25 West 45th Street, the Century Building.

Both Edna Ferber and F.P.A. contributed stories to The New Yorker in its debut year. ◆ ◆ ◆

The magazine debuted on Thursday, February 19, 1925, and was dated the following Saturday. The cover price was 15 cents, and the first printing was 15,000 copies. By late spring, circulation had dropped to 8,000, then dipped to a low of 2,700. The future looked rocky. James Thurber called it “the outstanding flop of 1925.” Ross and Grant burned through all their money, so Fleischmann had to pour more in. He nearly pulled the plug and let the magazine fold. However, at the May 1925 wedding of F.P.A. and Esther Sayles Root, Fleischmann told Ross that they would continue. The magazine would turn a profit three years later.

For the ten years that the magazine was edited in this building, scores of legends walked its halls. E. B. White joined in 1926, and James Thurber a year later. In 1928 John O’Hara started a forty-year association with the magazine. Adams kicked in for issue number 1 with a satirical piece on writing fiction, contributing to the magazine until 1949. Benchley, one of the highest-paid humorists in the country, wrote drama reviews and press criticism. When he went to Hollywood, Parker filled in for him. Connelly passed along humorous sketches and “Talk of the Town” contributions from 1926 to 1954. Kaufman wrote thirteen pieces, between 1935 and 1960.

Ferber gave Ross a two-page profile of journalist William Allen White in issue 15 in May 1925, when only a few thousand people were reading it. Heywood Broun’s first article for the magazine was a hilarious 1927 profile of himself, written in the third person. Margaret Leech helped make “Profiles” a unique new form of journalism, and wrote early ones in 1927–28 about female newsmakers such as Anne Morgan, who organized World War I relief efforts. Herman Mankiewicz attended the birth of the magazine and wrote drama reviews and marketing sales copy.

Parker anonymously wrote the debut issue’s theater page. (“Say what you will—and who has a better right?—about the present theatrical season, it has been a great little year for sex.”) Parker was a mainstay of the magazine until 1963, writing poems, short stories, drama reviews, book reviews, and casuals. In 1927 she was handed the reins of the “Recent Books” column, and assumed the alias “Constant Reader.” Parker’s most famous review was of The House at Pooh Corner by A. A. Milne. The Englishman got under her skin, and spying “hummy” on the page pushed her over the edge: “It is that word ‘hummy,’ my darlings, that marks the first place in The House at Pooh Corner at which Tonstant Weader fwowed up.”

Murdock Pemberton gave Ross a poem for the third issue. He wrote for the magazine until 1961. Without any formal fine art education, he was The New Yorker’s first art critic. Sherwood, editor of Life, profiled director Cecil B. DeMille in 1925. The next year he wrote about silent-movie star Harold Lloyd. Frank Sullivan had the longest association of any member of the Vicious Circle. He wrote humor pieces from March 1925 until December 1974.

Deems Taylor wrote a 1929 profile of conductor Walter Damrosch, and Peggy Wood, an actress turned writer, contributed to “Talk of the Town.” Woollcott wrote almost 250 pieces for the magazine, from 1925 to 1939. He created the “Shouts & Murmurs” department in 1929 and wrote it almost weekly for five years. Woollcott was legendary among the staff when it came to how difficult it was to edit and fact-check his copy. He and Ross had an acrimonious split, and Woollcott quit.

Other greats who came to the first location of the magazine in this era were Ogden Nash and S. J. Perelman in 1930, illustrator Charles Addams in 1933, and critic Edmund Wilson in 1934. In 1935 the staff outgrew the space and moved one block away. Since The New Yorker moved out, the building has housed many interesting tenants over the decades, including William F. Buckley’s Conservative Party, and the Samuel French Company.

Pomona in all her glory; Scott & Zelda Fitzgerald jumped into the fountain after their wedding. ◆ ◆ ◆

3. Second Office, 1935–1991

At the nadir of the Great Depression, The New Yorker was doing so well that it outgrew its office space. The magazine moved from West 45th to West 44th Street in 1935. The official name of the location is the National Association Building. The twenty-story tower was designed by Starrett & Van Vleck, and opened in 1920. The magazine eventually occupied seven floors in the building, with editors on floors eighteen through twenty.

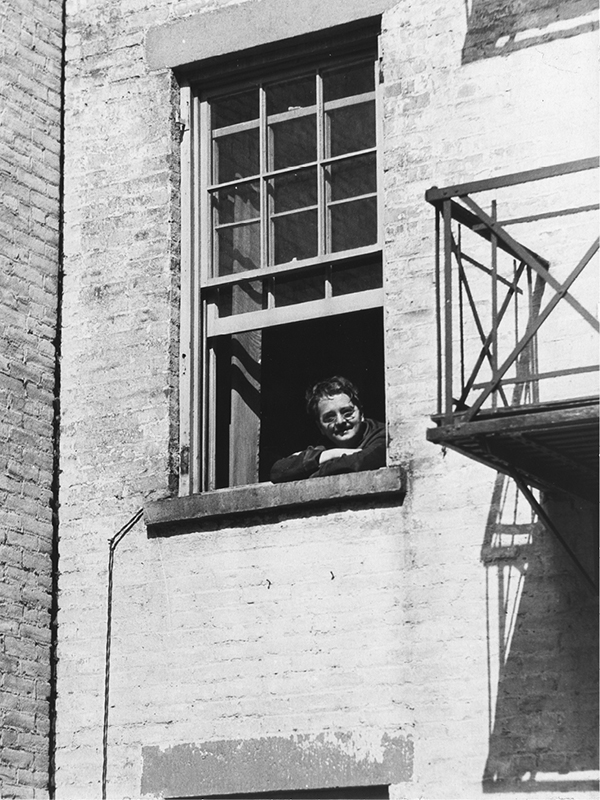

For almost sixty years The New Yorker was edited from this building that confusingly opens onto both 43rd and 44th Streets. From the elevators of 25 West 43rd Street, it takes five minutes to reach the lobby of the Algonquin Hotel. In this era, the magazine rose to international prominence. Ross was editor until his death in 1951, when his trusted lieutenant, William Shawn, took command for the next thirty-five years.

During these glory years the magazine cemented its reputation, and those elevators played a part in the magazine’s legend. Ross forbade staff from talking to him on the ride up or down the twenty floors, his theory being that he didn’t want to tip off other passengers that they were riding with the editor of The New Yorker. The magazine’s lease quirkily required that a manually operated elevator and operator had to be on duty.

Contributors drew scores of cartoons on the walls of the art department. James Thurber also drew cartoons on office walls, but one of the most memorable was in a hallway: a man breezily walking along, while around a corner a woman waited with a club in hand to whack him.

In 1991, six years after being sold to Advance Publications, the staff vacated the offices and moved sixty feet south, to 20 West 43rd Street. They lasted there for about ten years. In 2000, the magazine moved to the twentieth and twenty-first floors of 4 Times Square, on the corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue. This forty-eight-story building (nickname: The Death Star) is also home to GQ, Vanity Fair, and Vogue. In 2015 The New Yorker is scheduled to relocate downtown to One World Trade Center, at 285 Fulton Street, with the rest of Condé Nast.

4. Alexander Woollcott Apartment, Wit’s End

Alexander Woollcott wrecked a fantastic living situation with friends Jane Grant and Harold Ross, who should have received medals for putting up with the most difficult roommate of all time. Woollcott complained about everything at 412 West 47th Street, from the food to the party guests. Matters came to a head in the summer of 1927, not long before Grant and Ross separated. Grant asked Woollcott to leave because Ross despised personal conflicts.

The Campanile, 450 East 52nd Street. The breakfasts that Aleck Woollcott held here were legendary. ◆ ◆ ◆

The rotund critic decamped twenty blocks uptown, taking the tableware and household help with him. He moved into the Hotel des Artistes, 1 West 67th Street, a 1918 landmark that faces Central Park. He lived there for about three years; during this time his newspaper days ended, and his radio broadcasting career began. With his fat paychecks from CBS, Woollcott set up shop in the Campanile, 450 East 52nd Street, one of the most famous apartment buildings on the East River.

Franklin P. Adams suggested that Woollcott name his place “Ocowoica,” a made-up Native American word meaning The-Little-Apartment-on-the-East-River-That-It-Is-Difficult-to-Find-a-Taxi-Cab-Near. But Dorothy Parker came up with the name that stuck: Wit’s End. Woollcott’s third-floor apartment had a commanding view of the East River and overlooked a small garden below (lost when FDR Drive was constructed in 1938).

Wit’s End became Woollcott’s most famous address. Sunday breakfasts were the highlight, with Woollcott hosting in his pajamas and bathrobe, brunch filling up most of the day. He served his favorite dishes: eggs, sausage, French toast with maple syrup, pancakes, and jelly donuts. Anything that would clog your arteries, Woollcott served. Among the visitors here were Charlie Chaplin and Thornton Wilder. Although he lived alone—one of the rare occasions in his life—his friends weren’t far away. Peggy Leech and Ralph Pulitzer also lived in the building, and Alice Duer Miller lived across the hall. When his parties overflowed his space, he would walk over, open her door (unannounced), and the guests would spill over into her apartment. Frank Sullivan lived around the corner, and Parker took an apartment next door to Wit’s End at 444 East 52nd Street.

Designed by Van Wart & Wein, the Campanile opened in 1930. When it opened, the building sat on the river’s edge, and the Montauk Yacht Club moored its boats to the Campanile’s private dock. The exclusive fourteen-story co-op has fewer than twenty apartments and sits at the end of the block. Woollcott lived at the Campanile through the Thirties. But as his fame and wealth increased, he moved to 10 Gracie Square on the Upper East Side.

The New Yorker has devoted more attention to Grand Central Terminal than any other place in New York City. Since 1925, more than five hundred items and cartoons have made mention of the landmark destination. Since the magazine’s inception, the train station has been a ten-minute walk away and a constant source of inspiration for writers and cartoonists. Key staff members and contributors were commuters: F.P.A., Benchley, Ross, Thurber, and White, among them. Passing through the place ten times a week, they were bound to collect material.

In the magazine’s first year, Grand Central starred in “Talk of the Town” pieces and a cartoon by Joseph Fannell of flappers and men in boaters in the main concourse:

Watch-watching, harried, breathless, snatchy talkers.

They pass—commute, inglorious New Yorkers.

Cartoonists adore the four-faced clock above the information booth. A 1934 Helen E. Hokinson drawing shows a well-dressed woman pointing angrily to it, asking a porter, “Is that clock right?” The next year Charles Addams drew the same booth, without a caption, with a fortune-teller inside it.

In 1932, Thurber went inside the Grand Central office of John W. Campbell, who had a luxurious space tucked into a hidden corner of the station. “It’s sixty feet long, thirty feet wide; the ceiling is twenty-five feet above you. At a huge carved desk at the far end of the room sits Mr. Campbell, looking tiny.” Today, that space is the Campbell Apartment, a cocktail lounge and bar.

Grand Central Terminal sees almost 100 million visitors annually. ◆ ◆ ◆

The writer with the earliest affection for the station was E. B. White. Grand Central served as a constant source of inspiration for him. He wrote about train schedules, overheard conversations, station signs, and little annoyances. (He once called the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad “unimaginative” for failing to post the 5:10 to Stamford clearly.)

In 1949, White landed Ross in every newspaper in town. The dispute was broadcast ads and public address announcements in the station, which left White aghast and bemoaning “the racket in the Terminal.” Ross, who commuted between New York and Connecticut, must have agreed. He was asked to testify before the New York State Public Service Commission because the magazine had begun a letter-writing campaign against the station’s music and announcements. Ultimately he won, and that silence continues today.