Wit’s End

Gone But Not Forgotten

Death-bed promises should be broken as lightly as they are seriously made. The dead have no right to lay their clammy fingers upon the living.

—Edna Ferber

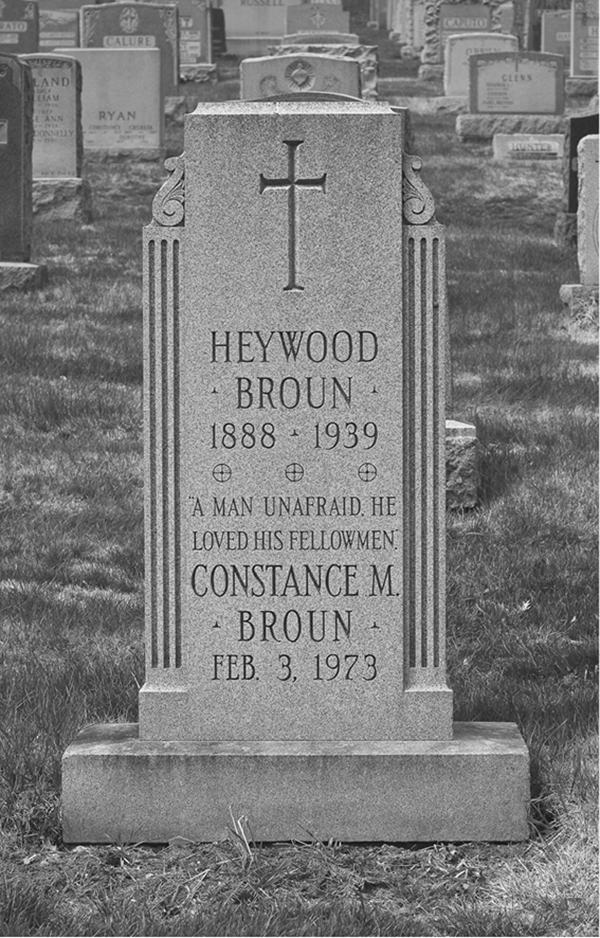

Heywood Broun is buried in Hawthorne, New York, one hour north of the city. ◆ ◆ ◆

Members of the Algonquin Round Table either rushed up to fame, grabbed it by the lapels, and shook it, or they retreated to secluded towns or villages and hid out for the remainder of their careers. There was rarely any middle ground with the Vicious Circle. When fame came, they ran with it. But it scared the hell out of some of them.

When the Thirties began, the daily meeting of the Round Table ceased. Some of the members clung to their friendships; others moved along. Their fame grew exponentially. The group made a name for itself immediately after World War I, but some of its number didn’t live to see the next one. The Round Table started dying off in the Thirties, lost more in the Forties, and was gone for the most part before Eisenhower took office. John V. A. Weaver went first, in 1938, and Margalo Gillmore closed the book in 1986. The New York Times noted the passing of many on the front page, including F.P.A., Benchley, Broun, Connelly, Ferber, Harpo, George S. Kaufman, Parker, Brock Pemberton, Ross, Sherwood, and Woollcott.

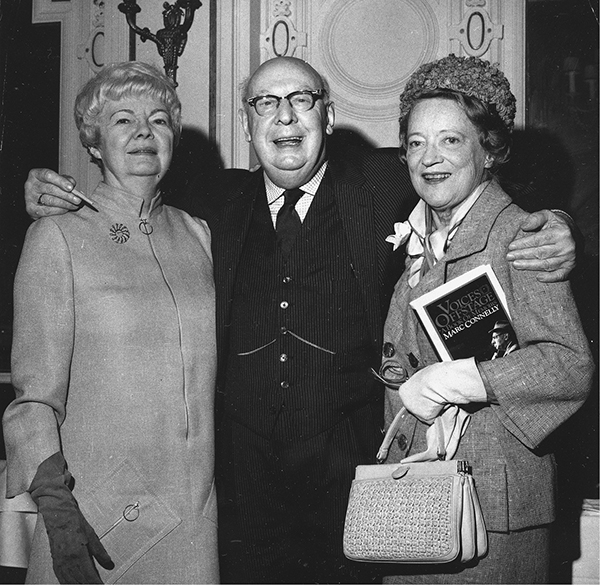

Margalo Gillmore, Marc Connelly, and Peggy Wood at the Algonquin in 1968. ◆ ◆ ◆

A few last, straggling meetings of the Vicious Circle took place over the years. First was the night in January 1943 that several went to the Algonquin after Woollcott’s memorial service. It was a sad, brief gathering made gloomier for the old friends by snow and darkness.

Nearly two decades passed before another gathering occurred, and that one was not even at the Algonquin, but at the Edison Hotel, 228 West 47th Street. In February 1961 the American National Theatre and Academy hosted a gala to salute its president, Peggy Wood, on the occasion of her fiftieth anniversary in the theater. Celebrating with Wood were Connelly, Grant, Gillmore, Taylor, and Frank Case’s daughter, Margaret. “There must be a gang such as ours somewhere today,” Grant said at the party. “But, of course, times have changed. For one thing, the writers nowadays all marry cuties. In our day, writers were sometimes drawn to more intellectual girls.”

The last true gathering of three founding members at the Algonquin took place in the Rose Room, in front of cameras, on the occasion of the publication of Connelly’s memoirs in 1968. Gillmore and Wood stood beside him four decades after the legendary group had broken apart. This is how the other members of the group wrapped up their lives:

The twilight of Franklin P. Adams’s life and career proved painfully sad. In a matter of a few years, he lost his newspaper job, radio show, and marriage. To make matters worse, F.P.A. probably suffered from undiagnosed dementia. Ross put his old army buddy on a lifetime stipend, which was honored after the editor’s death. Adams’s once-sharp memory failed him, and his personality, once just gruff, became harder to handle. When Esther Adams divorced him, she also sold the family house in Connecticut. F.P.A. had nowhere else to go, so he took a room at the Players Club. He was sixty-nine years old when he moved in, and his condition was deteriorating.

In 1951, his old friends hosted a wonderful tribute for him at the Players Club on the occasion of his seventieth birthday. Among the Round Tablers at the “pipe night” was Deems Taylor, whom F.P.A. had included in “The Conning Tower” almost forty-five years earlier. Another former contributor, Newman Levy, put together a special issue of Adams’s column for the occasion, with material provided by Edna Ferber, Morrie Ryskind, Frank Sullivan, and E. B. White. F.P.A’s oldest son, Anthony, attended and helped his father open the many gifts. A few years later, the old columnist’s condition deteriorated to the degree where he couldn’t live alone in the club any longer. In 1955 he was transferred to the Lynwood Nursing Home at 306 West 102nd Street. He lived on the second floor of the brownstone building for the last five years of his life. Aside from his ex-wife and children, he received almost no visitors.

He died on March 23, 1960, at the age of seventy-eight. His funeral took place at Frank E. Campbell’s, 1076 Madison Avenue. Among the two hundred mourners who attended were Connelly, Ferber, Peggy Leech, Ogden Nash, John O’Hara, and Taylor. Connelly gave the eulogy, which read in part: “Rejoicing in the truth, he used mockery in a civilized, therapeutic way. His wit was never mean. He hated only the ugly. He stimulated more young writers in the Twenties and Thirties than any other person. He was a constant, brilliant light.” Franklin P. Adams was cremated and interred in Westchester County.

Hardworking Robert Benchley stayed active until the end. In 1933, he began his first radio show, broadcast on CBS. He also appeared in forty-six movie shorts between 1928 and 1945. Columnist Sidney Carroll wrote in 1942, “The movies get a comedian and the literary muse seems destined to lose her most prodigal son for good. Literature lost out because so many people in Hollywood think Robert Benchley looks much funnier than he writes. And they keep him busy looking at the cameras instead of writing for them.” At the time, Benchley was on the Paramount lot making two forgettable films: Out of the Frying Pan and Take a Letter, Darling.

In his later years, near Grant’s Tomb in Riverside Park, Benchley partook in an early-morning ritual at a small fence around a lonely grave with the inscription:

Erected to the memory

of an amiable child

St. Claire Pollock

Died 15 July 1797

in the fifth year of his age

This monument, a hidden city secret, commemorates a boy who died nearby in 1797. Years later, when the city took over the land, planners respected the site and built the roadway around it. Benchley paid visits to it. ◆ ◆ ◆

near West 123rd Street and Riverside Drive. Bringing a friend with him to pay his respects, he got teary-eyed as he lamented his own wasted life, cowardice, weakness, and failure. Benchley, to the surprise of his companion, lamented that next to the Amiable Child, his own life had been squandered. Diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver and high blood pressure, Benchley suffered from health problems exacerbated by his heavy drinking.

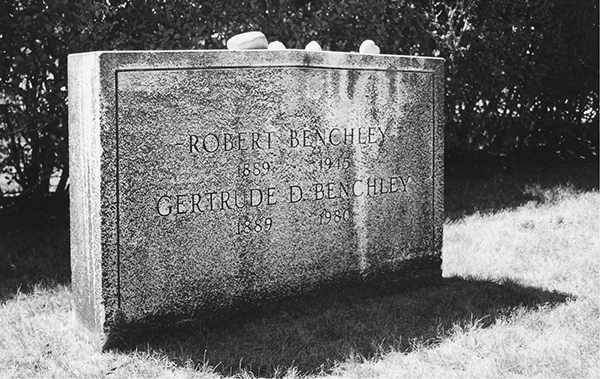

Throughout World War II Benchley kept up an extremely busy pace in Hollywood. He lived in a bungalow in the Garden of Allah and worked steadily in movies and radio. In late 1945, he returned to New York for a break, but his health slid downhill. He collapsed in his room in the Royalton Hotel at 44 West 44th Street. He died in the Harkness Pavilion at the Columbia University Medical Center at 180 Fort Washington Avenue on September 21, 1945. He was fifty-six years old. Following a private service, his body was cremated and the ashes given to his family. At the cemetery in Nantucket, however, the family discovered that the urn was empty. When the correct one was located, his remains were interred properly. His headstone, chosen by his son, Nat, was carved with his New Yorker byline. His wife is buried next to him.

Benchley is interred next to his wife on Nantucket Island. ◆ ◆ ◆

Another Round Tabler who worked until the day he died (relatively) young was Heywood Broun. As one of the top columnists in the country, Broun helped to found the Newspaper Guild—the highly controversial first union for newspaper reporters and editors—in 1933, and served as its first president. He traveled the country to attend strikes, rallies, and press conferences, running his health into the ground with constant travel, work, and drinking. He spent a lot of his nights in the Manhattan speakeasies and saloons favored by newspaper reporters.

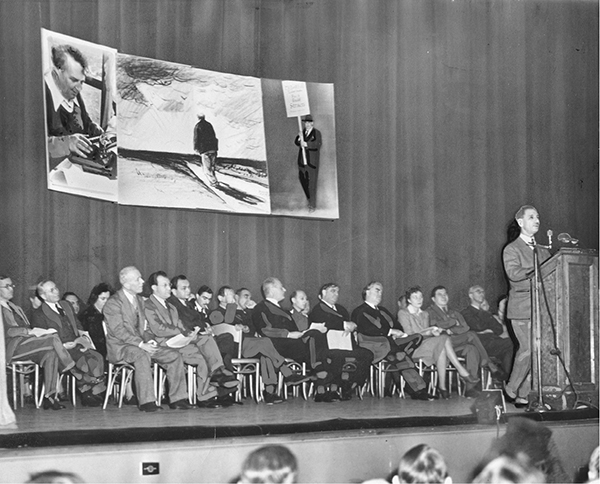

In February 1940, 12,000 people attended a memorial for Broun at the Manhattan Center. Among the speakers were F.P.A, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Edna Ferber, and John L. Lewis. ◆ ◆ ◆

At home in Connecticut, he and Ruth Hale had an open marriage and lived separate lives, but her death in 1934 still crushed him. Broun had been seeing a chorus girl named Connie Madison, a young widow from Yonkers. Following Hale’s death, he married Madison in January 1935 in the Municipal Building, with a ceremony later at St. Malachy’s, also known as the Actors’ Chapel, at 239 West 49th Street. The couple moved into Sabine Farm and renovated the house into such good shape that Eleanor Roosevelt came to a summertime picnic there in 1937. When Broun turned fifty, he wrote one of his best columns:

At 50 I have more faith than I had before. People are better than I thought they were going to be—myself included. In mere physical exertion there may be some let-up. Instead of the daily constitutional of a hundred yards it will be 25 from now on. But at 50 I’m a better fighter than at 21. I’m more radical, and things which once were just sort of sentimental solace are now realities.

The former sportswriter never won a Pulitzer Prize, but he did achieve something better. On Christmas Eve, 1938, President Roosevelt, in his annual holiday radio address to the nation, read aloud one of Broun’s columns to millions of listeners. It was a New Testament story, given an even more spiritual twist. Less than a year before he died, Broun began taking instruction from Monsignor Fulton Sheen and was baptized a Roman Catholic. “I have a strong premonition of death,” Broun said to the priest.

In the fall of 1939 Broun came down with pneumonia and was taken to the Harkness Pavilion. He died on December 18 at age fifty-one. More than three thousand mourners packed the Cathedral of St. Patrick to attend his funeral mass. Monsignor Sheen delivered the eulogy. Most of the Round Table attended, as well as Mayor La Guardia and Newspaper Guild members. Broun was buried in Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York, not far from where Babe Ruth was later laid to rest.

The Green Pastures earned Marc Connelly a Pulitzer Prize, a gorgeous movie-star wife, and fifty years of dining-out stories. The wife didn’t work out—he never mentions Madeline Hurlock Connelly, later Mrs. Robert E. Sherwood, in his 1968 autobiography—but the Pulitzer opened doors and set dinner tables for him. Connelly coasted on his 1930 fame for the rest of his life, and never accomplished much afterward. His collaborations with George S. Kaufman peaked during the Prohibition era before the partnership fizzled. In 1934, after the publication of a newly discovered novel that Charles Dickens had written for his children, Kaufman made a famous jab at his old writing partner: “Charles Dickens, dead, writes more than Marc Connelly alive.” Connelly became a perennial Manhattan dinner party guest and Hamptons weekend houseguest.

In November 1980, Connelly celebrated his ninetieth birthday at City Hall at a party hosted by Mayor Ed Koch. Helen Hayes and Governor Hugh Carey paid tribute to his achievements. “I’m so old that I can withstand unearned compliments,” Connelly said. “I’m grateful for being alive and for being a citizen of New York, which I think is the loveliest city in the world.” Connelly died six weeks later, on December 21, 1980, while addressing Christmas cards in St. Luke’s Hospital at Amsterdam Avenue and 114th Street. The turnout at the memorial service at Frank E. Campbell’s was amazing. John Guare, Ruth Gordon, David Mamet, and Stephen Sondheim attended, representing the theater world, old and new. Benchley’s son, Nathaniel, delivered the eulogy. Connelly is interred in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, in an unmarked grave.

It took two autobiographies for her to get her life story out, and when Edna Ferber was done, her life read like one of her bestsellers. “Life can’t ever really defeat a writer who is in love with writing,” she said, “for life itself is a writer’s lover until death.” When the final tally came in, she had written twelve novels, more than a hundred short stories, and collaborated on six plays. Most of her novels were bestsellers, her short stories sold for the highest fees going, and half of her shows succeeded at the box office. With the royalties from Show Boat and the James Dean epic Giant, Ferber lived her last years in style. Her last apartment was at 730 Park Avenue. She died of cancer there on April 16, 1968. She was cremated, and her funeral was held, like so many others’ of the group, at Frank E. Campbell’s. Connelly and Richard Rodgers mourned along with a hundred others from the world of publishing and Broadway. Ferber once said that she hoped to be remembered as “a receptive and perceptive human being who has loved life and enjoyed living, and to whom the world owes exactly nothing.”

The last surviving member of the Vicious Circle was Margalo Gillmore, who lived to see the space shuttle flights and a fellow actor in the White House. Gillmore stayed remarkably busy throughout her career, which spanned early Eugene O’Neill plays—with direction from the playwright himself—silent films, starring roles on Broadway, major Hollywood hits, and, finally, television. When she was sixty-seven, Houghton Mifflin published her autobiography, Four Flights Up, about growing up in Manhattan and breaking into acting. In it she wrote, “Chance plays a large part in an actor’s life. Opportunity, even destiny, may hang on its light and gossamer thread.” Gillmore died in her Upper East Side apartment on June 30, 1986, at the age of eighty-nine. She’s interred next to her parents and husband in Kensico Cemetery.

Father and daughter buried together in Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York. The symbol of Actors’ Equity Association adorns their gravestone; both were early members. ◆ ◆ ◆

F. Scott Fitzgerald attended parties at Jane Grant’s home in Hell’s Kitchen, but when he wrote “there are no second acts in American lives,” he certainly didn’t have his old friend in mind. After Grant and Ross split, the divorce spurred her to rethink her life. She went to China, Russia, and Germany in the years leading up to World War II, and filed stories for the Times. In 1939 she married a Fortune editor, William Harris, and split her time between a city apartment on Park Avenue and the couple’s White Flower Farm in Litchfield, Connecticut. In 1950 she restarted the Lucy Stone League, a throwback to the first feminist movement of the Twenties. “Mrs. doesn’t mean married,” she told a reporter. “It means mistress of one’s own affairs. The last definition of it given in Mr. Webster’s dictionary gives it as the appellation for a wife.”

In 1968, Reynal published her memoir, Ross, The New Yorker and Me, a warm look at the Round Table, her role in the birth of the magazine, and the bittersweet memories of watching her ex-husband succeed from afar. But Grant’s real success came on the farm. She and Harris turned the little retail seed business into one of the most popular garden-supply firms in the Northeast. After her death, her husband sold the farm in northwest Connecticut. It still operates today and is wildly popular. One of the loveliest items the farm sells is the red and pink Jane Grant Rhododendron.

Grant died of cancer in her farmhouse on March 16, 1972. The Times callously buried her obituary on page 44, an ignoble tribute to a pioneer it called “the city room’s first woman reporter.”

None of the Vicious Circle had a gloomier end than Ruth Hale. At one time, she had a lively presence on the metropolitan scene, wrote for the best newspapers and magazines around, and hosted brilliant house parties on the Upper West Side with raconteur husband Heywood Broun. But as the Twenties drew to a close, she withdrew from life and spent her days alone at Sabine Farm in Stamford, Connecticut, living in a rural shack with almost no amenities, cutting herself off from old friends, and alienating Broun and their teenage son, Woodie.

By late 1933 she had been a recluse for almost five years. She went to Nogales, Mexico, and obtained a quiet divorce on the grounds that she and Broun had lived apart for more than five years. The news didn’t come out in the papers until three months later. By then she was saying to friends, “ ‘Ruth Hale, spinster,’ I like it quite well. I can go back to my friends as Ruth Hale. At least I won’t have that god-awful tag, ‘Mrs. Heywood Broun.’ ” But the divorce did little to calm her soul. She was forty-seven years old and not well. “After forty a woman is through,” she told a friend. “I’m going to will myself to die.” Her health deteriorated rapidly. She lost the use of her legs, became weak, stopped eating, and refused medical care. On September 18, 1934, she lapsed into unconsciousness at Sabine Farm. Broun rushed her to Doctors Hospital at 170 East End Avenue, but it was too late.

The farm where Ruth Hale retired to live, and eventually end her days. ◆ ◆ ◆

Her son said later, “At her own wish she was cremated, and because she had not wanted one, there was no sort of memorial service. One day she was there and the next day she was gone.” Hale’s mother took her ashes home to Tennessee—without telling Broun or their son—and secretly buried her daughter’s remains in the family plot in the Old Rogersville Presbyterian Cemetery under a headstone that sadly ignores all of her daughter’s accomplishments. It omits her lifetime passion for independence and feminism:

Ruth Hale

Daughter of Annie Riley and J. Richards Hale

And For 17 Years the Wife of Heywood Broun

Beatrice Kaufman was the opposite of Ruth Hale in every way but one: Each tolerated her husband’s numerous affairs. While the Kaufmans lived at various posh addresses around the city, George always held on to a rented apartment somewhere on West 73rd Street where he conducted his liaisons. Bea had her own young paramours to squire her around the city. For the last dozen years of her life, Bea worked in publishing as a reader and editor, and for Samuel Goldwyn as a script reader. But her real job was as Mrs. George S. Kaufman, supporting and encouraging him unconditionally. In the fall of 1945 she became sick, and after a brief illness she died on October 6, 1945, in their apartment at 410 Park Avenue. She was fifty years old.

Friends made a condolence call to the apartment after her death. Ross wrote to Frank Sullivan, “After twenty words of monosyllables and three-word sentences widely spaced, George cut loose that Sunday and talked his head off. It was a very unusual thing.” Kaufman wasn’t a religious man, but he devoted himself to her memory. Each year on the anniversary of Bea’s death, George honored her by lighting a yahrzeit candle, which burned for twenty-four hours in his bedroom.

Following his wife’s death, George S. Kaufman went into a deep depression. Only after he met beautiful blonde British actress Leueen MacGrath in 1948 did he find life worth living again. She was thirty-four years old and had been married twice. He was fifty-nine, and after his second marriage, to her—held at his Barley Sheaf Farm the next year—Kaufman got back to work.

He played the curmudgeon as a panelist on CBS’s This Is Show Business in 1949 and got into hot water for his wisecracks. He had one more stage hit, The Solid Gold Cadillac, which ran for 526 performances at the Belasco and Music Box theaters from 1953 to 1955. His collaborator was Howard Teichmann, a young playwright who worshipped Kaufman. Teichmann wrote the definitive biography of the man, which he admitted proved difficult: “I saw Kaufman almost daily for the last ten years of his life. . . . I thought I knew George S. Kaufman reasonably well. That was a mistake. I hardly knew him at all.”

Not long after Kaufman’s final success, he started showing signs of dementia, sitting in the lobby of his Park Avenue apartment in his bathrobe, for example. He had to quit playing card games because he couldn’t remember what cards he had played.

His health deteriorated rapidly by 1960, and he cut his ties with his old friends and insulted others, such as Edna Ferber. Living alone at 1035 Park Avenue, he suffered a series of strokes. He died on June 2, 1961, of heart failure. A memorial service was held at Frank Campbell’s, which would be the location for many Round Table funerals. The Times said in a tribute the next day, “As writer, play doctor and director, he had a hand in the making of a joyous series of Broadway successes.”

Of all the group, Margaret Leech may have had the greatest inner strength and drive to succeed in the face of hardship. Her first child died in infancy. A widow at age forty-five, she raised her daughter by herself, and outlived her. With her late husband’s money she could have lived a life of leisure on the Upper East Side, but instead she worked as a biographical researcher and earned two Pulitzer prizes. She toiled alone in her apartment at 120 East End Avenue, surrounded by her books and research materials. But in her seventies, she took particular delight in her grandchildren and in hosting cocktail parties. “I am sure about one thing,” she said. “It’s that I won’t give a big all-purpose cocktail party. Living way over here on the East Side, I feel that if people make the effort to visit me, they should be fed.”

Buried with her family and next to father-in-law, Joseph Pulitzer, Margaret Leech is interred in Woodlawn Cemetery. The stone carver originally misspelled her surname. ◆ ◆ ◆

In the Fifties, she devoted her time to In the Days of William McKinley, published in 1959. The New York Times Book Review called it a “first-rate study of a second-rate president.” In the Sixties, she doted on her grandchildren by taking them to Broadway shows.

In the last years of her life, she moved to the fourth floor of 812 Fifth Avenue, a nineteen-story cooperative, and worked even harder on her final book, about President Garfield. An accidental apartment fire in September 1972 caused second- and third-degree burns on her hands and feet. Two years later, she suffered a stroke and died in her apartment on February 24, 1974. She was eighty years old. Leech is interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, next to her husband and children in the beautiful Pulitzer family plot.

For a woman who marched in suffragette parades, rode circus elephants, and chased fire engines, Neysa McMein’s last years were dull and painful. Her glamorous career as a magazine cover illustrator came to a screeching halt when editors switched to photography. She never recovered from losing her $30,000-per-year McCall’s contract in 1938. Some of her wealthy friends took pity and asked her to paint their portraits, but her heart really wasn’t in it. McMein spent her final years visiting with Woollcott at their Vermont lake house and seeing friends.

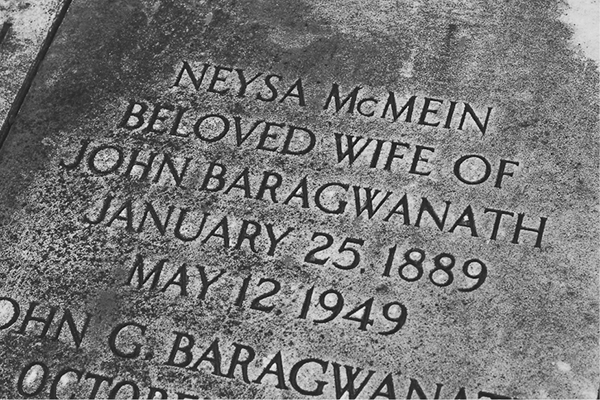

The last apartment McMein lived in was 131 East 66th Street. In April 1942, while sleepwalking, the fifty-four-year-old fell down the stairs. She broke her back and spent months recovering at home. In the Forties, with no painting work, she turned to her other love, writing. She collaborated with Jane Grant on a movie script about a beautiful artist in her twenties, the most popular woman in town. They never completed it, nor was it ever produced. By the end of the decade McMein was so weak that moving around was difficult; unbeknownst to her, because her husband kept it from her, McMein had cancer. On May 12, 1949, she died at St. Luke’s Hospital at age sixty-one. Her funeral took place at Holy Trinity Episcopal Church. McMein is interred in Rhinebeck Cemetery in Dutchess County, New York, next to her husband, John Baragwanath.

Neysa McMein is interred next to her husband in Rhinebeck, New York. ◆ ◆ ◆

When Herman J. Mankiewicz won his Oscar for writing Citizen Kane, he learned about the award on the radio. He was so convinced that he’d lose that he hadn’t bothered to attend the ceremony. The 1941 award marked the high point of his career, and he slid downward thereafter. Throughout the Forties and early Fifties, he suffered from deep depression. He stayed in his bedroom on Tower Road in the Bel Air section of Los Angeles, secluded and in his bathrobe. When he did venture out, he got drunk and into car crashes. Eventually he had to give up gambling and drinking when his money ran out. At the end of his life he had so many debts that he had to sell his beloved library, among the best book collections in all of Los Angeles.

In 1943 Herman Mankiewicz got into an auto accident in front of William Randolph Hearst’s house in Los Angeles. Hearst played up the drunk-driving case in his newspaper chain. ◆ ◆ ◆

Mankiewicz suffered from liver and circulation problems, and in early 1953 was taken to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital and put into an oxygen tent. To his wife, Sara, he spoke his last words before slipping into a coma: “Well, that finishes everything I’ve to take care of before I go to meet my maker. Or in my case, should I say co-maker?” Mankiewicz died on March 6, 1953, at age fifty-five. He requested a nonreligious funeral without flowers. His remains were cremated, his ashes scattered.

Harpo Marx made the journey from an Upper East Side tenement to a California mansion with a swimming pool, but his personality essentially remained the same throughout his life. From the moment he and his brothers became overnight sensations in 1924, and for the next forty years of his life, Marx made headlines and became a little more famous than he had been the day before.

After the Round Table split up, Harpo, Groucho, and Chico stayed busy making movies with Kaufman and Mankiewicz. Harpo visited Woollcott’s home in Vermont and bought shares in it as a full partner. Harpo even made a solo trip to Russia in the Thirties (possibly as a spy for the US ambassador). As his fame grew, so did his circle of friends. He visited the French Riviera, and he socialized with Somerset Maugham, George Bernard Shaw, and Jack Benny. The Marx Brothers made their last film, Love Happy, in 1949. Groucho went into radio and then television, while Harpo and Chico played nightclubs. In the Fifties, Harpo performed one-man shows of his comedy routines and harp solos, but he spent most of his days in California with his four adopted children.

In 1959, Harpo announced that he was retiring from public life. Five years later, on September 28, 1964, he died in Mount Sinai Hospital in Hollywood following heart surgery. He was seventy years old. The final resting place of his remains is still something of a mystery. His body was cremated and supposedly interred at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles, but popular legend has it that someone sprinkled him into a sand trap on the seventh hole of a golf course in Rancho Mirage, California.

In the Thirties, William B. Murray became a pioneer in the advertising business by packaging radio stars with advertisers to sell broadcast sponsorships. From his years in journalism he had developed incredible connections with Broadway stars and musicians. He joined the William Morris Agency just as radio was coming into its own, and he was there when television started. As head of the Radio and Television Department, he got rich representing Jimmy Durante, Al Jolson, and Fanny Brice. His personal life, however, was a shambles. Married three times, Murray moved to 333 East 57th Street. His second wife, actress Ilka Chase, divorced him in 1946. Almost immediately he married a young interior decorator, Florence Smolen, who bore him twin boys.

Two years later, he died at Harkness Pavilion on March 10, 1949, at age fifty-nine. His son by his first marriage, William Jr., grew up to become a notable New Yorker staff writer and editor. In 2000, not long before his own death, William Murray fils wrote about growing up with a distant father, bisexual mother, and her lover, Janet Flanner.

After early triumphs, Dorothy Parker coasted on her fame in Hollywood with a modicum of success in the Thirties and Forties. She earned two Academy Award nominations, but she held screenwriting in such low regard that they meant little to her. She spent the Fifties in and out of love with her second and third husband, Alan Campbell, and shuttling between New York and Los Angeles. She settled into a routine of writing the occasional short story for The New Yorker, gratefully accepted and published by editor William Shawn. She wrote the odd book review for Esquire, which gave her a steady paycheck in addition to book royalties from the Viking Press. Her final major project was collaborating with Arnaud d’Usseau on The Ladies of the Corridor, a coruscating look at female loneliness that briefly ran at the Longacre Theatre in the fall of 1953.

In 1935 Parker visited W. C. Fields on the set of David Copperfield. ◆ ◆ ◆

She spent the rest of the Fifties living on the fringes of cultural attention, occasionally popping up to give an interview or to accept an award. Unlike many of the group, she never wrote about herself late in life. Parker told friend Quentin Reynolds, “Rather than write my life story I would cut my throat with a dull knife.” Occasionally the FBI sent agents to her door to check on the old radical, but she waved them off. She was called before an investigative committee, but nothing came of it. Alan Campbell killed himself in their West Hollywood house in June 1963, which sent Parker packing back to New York.

Parker’s cremains were interred in Baltimore outside the NAACP headquarters, twenty-one years after her death. ◆ ◆ ◆

She settled into her apartment at the Volney Hotel at 23 East 74th Street, which she liked because there seemed to be as many small dogs as people in the building. During her last years, she battled an onslaught of illnesses and falls, but her mind remained as sharp as ever. Her heart gave out on June 7, 1967, when she was seventy-three years old.

Parker surprisingly left her estate to Martin Luther King Jr., a man she knew only through the media. Lillian Hellman, her longtime frenemy, was appointed to take care of Parker’s affairs, but she made a miserable mess of it. Hellman pitched the contents of Parker’s apartment, tossing all her papers and letters into the garbage. After a brief funeral service at Frank E. Campbell’s, Parker’s cremains went unclaimed for nearly twenty years, sitting in a filing cabinet at the law office of her deceased attorney. In 1988, her remains were brought to Baltimore and interred in a small garden outside the headquarters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

When Brock Pemberton died on March 11, 1950, his old newspaper, the Times, said in his front-page obituary, “His success was in the traditional pattern of the small-town boy making good in the big city.” His Kansas roots may have captured the paper’s imagination, but once in New York, Pemberton carved out a career from low-paid drama critic to one of the most successful Broadway producers between the two world wars. His last success was also the biggest of his thirty-year stage career. He bankrolled and produced Harvey, which ran for 1,775 shows, from 1944 to 1949, and won the Pulitzer Prize. His marriage to Margaret McCoy Pemberton lasted for thirty-five years, although some believe he had an affair with actress-director Antoinette Perry, his longtime collaborator and friend.

In his sixties, Pemberton suffered from heart problems, but his success with Harvey invigorated him so much that he went on road company productions and even got into the cast. In the last week of his life he saw the show in Phoenix, then took a train back to his native state to see it in Topeka. He returned home to 455 East 51st Street and died of a heart attack there. He was sixty-four years old. Pemberton’s funeral took place at the Methodist Christ Church. The next year, the American Theatre Wing, which he had helped found, presented him with the first posthumous Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Theatre, the Tony.

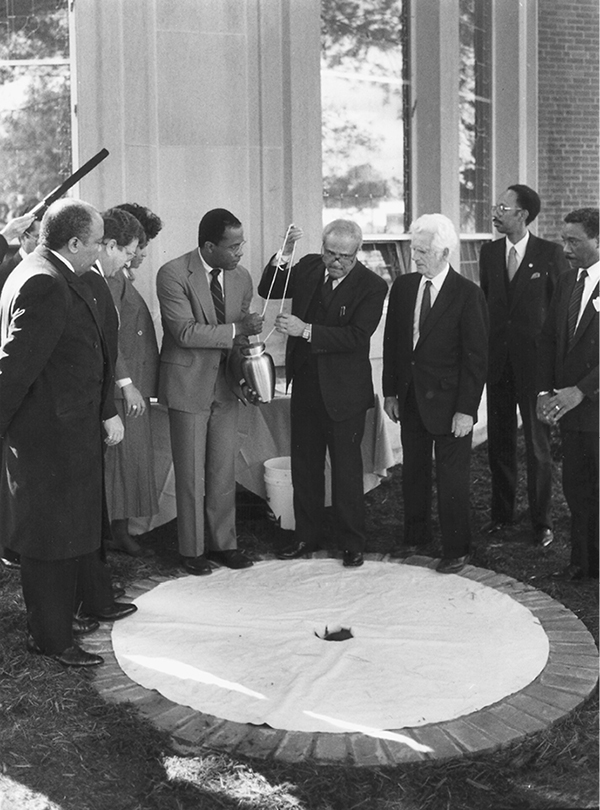

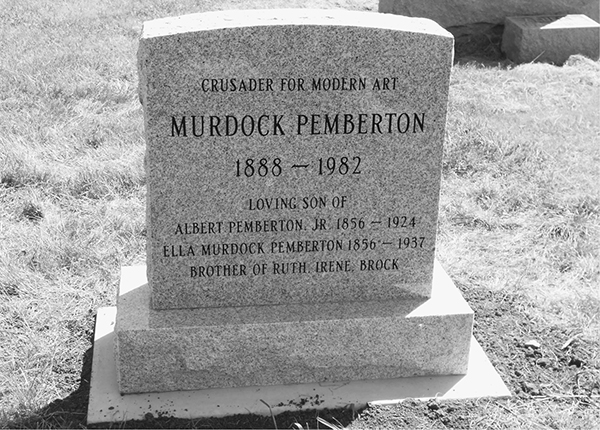

Murdock Pemberton got the Vicious Circle going by inviting John Peter Toohey and Alexander Woollcott to visit the Algonquin Hotel together, which sums up the most important event in his life. Pemberton didn’t have the grand success of his older brother, although he lived thirty years longer. His last two decades were rough. With no freelance writing work, he went back to The New Yorker, where he’d served as the first art critic, and took a job in the mailroom. His second wife, Frances, answered phones there for fourteen years. When she died in 1969, the Times flubbed the notice and printed that Murdock Pemberton had predeceased her. In 1974 Pemberton and Connelly went back to the Algonquin for the book launch party for a biography of Kaufman. Pemberton, age eighty-six at the time, said he took almost as much pride in founding the Round Table as he did in his children and grandchildren.

On August 18, 1982, he died in his sleep at his Catskills home in Valatie, New York. He was ninety-four years old. William Shawn remembered him as “knowledgeable, intelligent, astute and idiomatic in his writing. As a man he was of some formality and dignity, and charm.” Thirty years after his death, granddaughter Sally Pemberton wrote a meticulously researched book about his career and dedicated a beautiful cenotaph to him at Maplewood Memorial Lawn in his birthplace, Emporia, Kansas.

Cenotaph to Murdock Pemberton in Emporia, Kansas. ◆ ◆ ◆

The last twenty years of Harold Ross’s life weren’t easy. He had chain-smoked since his teens, and the stresses of running The New Yorker gave him health problems that required him to take a series of absences from the office to recover from operations. His personal life had never gone smoothly, either: He had three failed marriages, but also a young daughter whom he adored. Ross did live long enough to mark an important milestone, the 1950 party to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the magazine he had launched with Jane Grant. (She skipped it.) “We’ll go on as before—with luck,” he told a reporter. Ross’s luck ran out when he developed lung cancer. “I’m up here to end this thing, and it may end me, too,” he said to his old friend Kaufman before surgery. “But that’s better than going on this way. God bless you. I’m half under the anesthetic now.”

Ross died on the operating table at New England Baptist Hospital in Boston on December 6, 1951. He was fifty-nine years old. Frank Campbell’s hosted the memorial service, but whoever planned it wasn’t expecting a crowd and booked a small chapel. Staff members, friends, and strangers packed the chapel and the entranceway. Another hundred souls spilled onto the sidewalk. As an usher passed Margaret Case, whom Ross had hired in the Thirties, she heard him say, “Goddammit! We got to get some chairs in here!” Ross’s remains were cremated and given to his daughter. The old editor asked that his ashes be taken to the Rocky Mountains, where he was born, and sprinkled there.

By late 1937, Arthur Samuels was finished at Harper’s Bazaar and had signed with radio network WOR to read scripts and produce programs. Like Woollcott, he turned from magazines to broadcasting. He and his wife lived at 50 East 72nd Street. However, his radio career lasted only six months. On March 20, 1938, he died in Doctors Hospital after a brief illness at age forty-nine. His funeral was held at the former location of Frank E. Campbell’s on Broadway and West 66th Street. He was cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery.

During World War II, Robert E. Sherwood became more politically active than in any other time of his life. In June 1940, he paid $20,000 for a full-page newspaper ad that read stop hitler now. Isolationists attacked his next play, There Shall Be No Night, about the Russian invasion of Finland, but it won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1941. When the United States declared war on Japan and Germany, he went to work in Washington. Sherwood became President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, and went to Europe as director of the Office of War Information. His book Roosevelt and Hopkins won him his fourth Pulitzer in 1949. In 1950, he became a member of the National Academy of Arts and Letters.

Sherwood maintained a hectic work schedule in the Fifties. He moved to 25 Sutton Place South, where he worked on his last play, Small War in Manhattan. He suffered from circulation problems, partly due to his height, and also from the gas attack he had suffered in World War I. On November 14, 1955, Sherwood died of heart failure at New York Hospital. He was fifty-nine years old. Most of the surviving members of the Vicious Circle attended his funeral at St. George’s Episcopal Church at 209 East 16th Street. More than five hundred mourners heard a eulogy written by Maxwell Anderson and delivered by Alfred Lunt, which said, in part: “A man’s writings can contain only a part of him. Probably it’s always true that the man is bigger than the work he can leave behind. Let us try to remember what we can of Bob and keep it vivid and clear. While we have him in our minds he still moves among us and has an influence on our lives.”

Laurence Stallings was given a military burial and is interred in San Diego. ◆ ◆ ◆

Laurence Stallings had a tumultuous time in the Thirties. He couldn’t choose between literature and motion pictures. He and Benchley could be spotted at “21” together, both men struggling with the same issues of working for art or commerce. In 1934, Stallings became an editor of Fox Movietone News, offices at 460 West 54th Street, and lived at 50 East 77th Street. Anticipating the next world war, Fox sent him to Ethiopia in 1935 for what turned into a two-year assignment. His four cameramen recorded 50,000 feet of film as they waited for Mussolini to invade, which he did that year. Stallings filed stories for the New York Times on the conflict and then returned home to America. He abandoned his first wife and two small daughters and remarried in 1937.

After America entered World War II, Stallings went back on active duty with the Marines in 1942. He served as an intelligence officer in the Pentagon and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. Afterward, he returned to California to write screenplays, magazine articles, and books in Pacific Palisades. His health deteriorated, and doctors had to remove his other leg in 1963, the same year that Harper & Row published The Doughboys, his stirring account of World War I. Stallings died on February 28, 1968, at his home. He received a military burial with a US Marine Corps honor guard in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery outside San Diego.

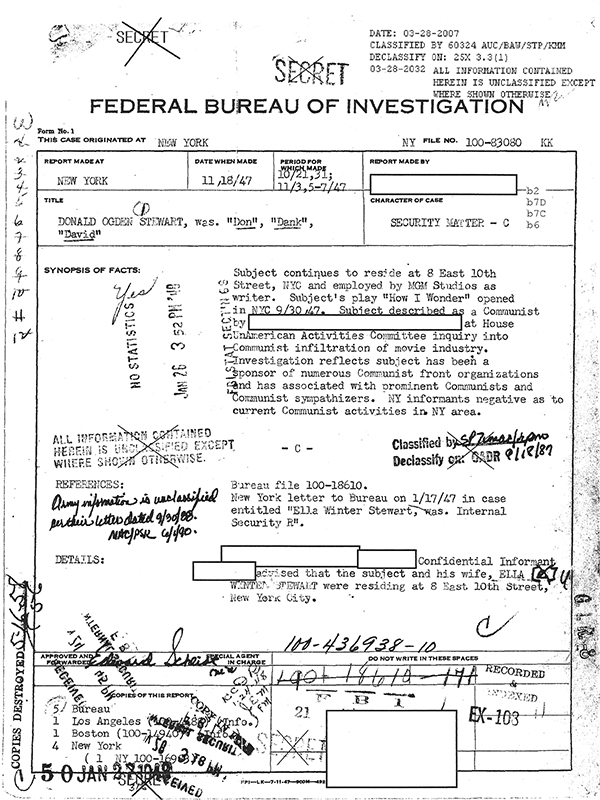

In 1951 Donald Ogden Stewart didn’t know that he would become the Algonquin Round Table’s own Philip Nolan. He and his second wife, noted communist Ella Winter, sailed from New York to London to produce a play. There, on a whim, they rented a house and decided to stay awhile. Unbeknownst to Stewart, the FBI had compiled a dossier of more than two thousand pages on him, tracking his left-wing activities. Agents had even followed him around New York and California. To date, some of his file still remains classified. While in England, his passport expired, and at the US Embassy he found that he was on a blacklist of “Red” Americans. The agency had an unwritten policy that the secretary of state could choose who could receive a passport, based on political beliefs. In this same way, singer Paul Robeson was denied a passport for more than seven years.

But Stewart fought it. In 1957 he sued in US federal court from London to reverse the ruling. Stewart won on the grounds that he didn’t have to say whether he had had any communist connections for the previous fifteen years. The US Court of Appeals upheld the ruling.

However, the four-year dispute came as a Pyrrhic victory. Stewart never used the passport to return to America, and never saw New York again. He and Winter lived a quiet life in Hampstead. He did little work, but old friends such as Ingrid Bergman, Charlie Chaplin, Katharine Hepburn, and James Thurber visited. On August 2, 1980, Stewart died of heart failure at his home at age eighty-five. His wife died of a stroke two days later. In his autobiography, published five years earlier, Stewart concluded: “My life has been for me a successful one, and in many ways a happy one. Can one ask more?” His remains were cremated.

After the demise of the New York World in 1931, Frank Sullivan moved home to Saratoga Springs and became the ultimate freelancer. In a small clapboard house shared with his sister at 135 Lincoln Avenue, he turned out marvelous humor pieces for the rest of his career. “Once I visited New York for twenty years, but I wouldn’t live there if you gave me Philadelphia,” he wrote. “A small town is the place to live. I live in a small town 180 miles from New York, and while I would not say it has New York beat by a mile, I would put the distance at six furlongs.”

Over the years, New Yorkers like Ross and Connelly visited Sullivan, who took them to the track, two blocks from his house, where he was treated like royalty. He picked up the nickname “The Sage of Saratoga,” and worked until his early eighties. He wrote for The New Yorker for fifty years as well as the Times sports section, the Saturday Evening Post, and Town & Country, his work collected in half a dozen books. Sullivan suffered a series of falls in his home, and his health deteriorated. He died in Saratoga Hospital on February 19, 1976, at age eighty-three. He is buried in the family plot in St. Peter’s Cemetery, in Saratoga Springs.

Frank Sullivan’s returned to Saratoga Springs. He is interred in the local Roman Catholic cemetery with his family. ◆ ◆ ◆

One of the more complex members of the group, Deems Taylor was the first successful American opera composer, and ranked among the first radio stars because of his authority and knowledge about classical music. He drew a national audience as a broadcaster, but he wanted to be known as a composer—despite the classical genre shrinking drastically year after year. Taylor received a measure of fame from narrating the Walt Disney classic Fantasia, but it wasn’t enough professionally.

Deems Taylor and his third wife, Lucille Watson-Little, whom he married in 1945. ◆ ◆ ◆

The multitalented composer had a messy personal life. He married and divorced three times. His third wife was nineteen years old when Taylor, then fifty-nine, met her. The marriage lasted for eight years. When he was older, his second wife, Mary Kennedy, came back into his life to help manage his affairs with their daughter, Joan.

In his sixties he turned to other pursuits. He served as president of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) from 1942 to 1948. He even helped judge the Miss America pageant. In the last dozen years of his life, Taylor grew increasing feeble. He moved in with his daughter’s family in 1963. He collapsed in May 1966 and was taken to the Medical Arts Center Hospital at 57 West 57th Street, built on the same spot where Neysa McMein’s famous studio-salon and Dorothy Parker’s apartment had been forty years before.

Taylor lingered in a coma until his death on July 3, 1966. He was eighty years old. At his funeral at Frank E. Campbell’s, Marc Connelly and John O’Hara served as two of the pallbearers. Taylor’s remains were taken to the Kensico Cemetery, twenty-five miles north of the city, in Valhalla. He is buried next to his nephew, William O. Davis.

Taylor is buried in Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York. ◆ ◆ ◆

In June 1919, publicity man John Peter Toohey uttered the sentence—“Why don’t we do this every day?”—that bonded the group. A fun-loving soul, he played the straight man for the many gags and practical jokes at the table. From 1930 to 1942, he worked for producer Sam H. Harris on such hits as the Berlin-Hart As Thousands Cheer and the Kaufman-Hart smash, The Man Who Came to Dinner. Toohey’s domain was the Music Box Theatre. His last credit was also a Kaufman and Hart show, The Late George Apley, which ran for almost four hundred performances, between 1944 and 1945. Toohey, who lived with his wife, Viola, at 43 Fifth Avenue, died on November 8, 1946, at the Beth Israel Hospital, First Avenue at East 16th Street. He was sixty-seven years old. His funeral was held at the Actors’ Chapel, St. Malachy’s Church, at 239 West 49th Street, and he was buried at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Pleasantville, Westchester County.

In The New Yorker’s fourth issue, David H. Wallace made the “Talk of Town.” On the eve of presenting a new play, Brock Pemberton was discussing a clothing sale and explaining that he had waited forty-five minutes to buy a new shirt. “What do you want to buy a new shirt for?” said Wallace. “You’ll only lose it next week.” The next year, the magazine reported that, after suffering through a well-attended concert by a diva whose voice wasn’t what it used to be, Wallace remarked, “Well, her cash registers are still good.”

Wallace had been a theatrical press agent and company manager for twenty years, and in the Thirties he went back to his professional origins: journalism. He wrote feature stories for the Times and freelance magazine articles. In 1945 he returned home to Syracuse and wrote about theater and art for the Herald-Journal, the same paper at which he’d worked more than thirty years earlier. Ten years later, after he developed a heart condition, he moved to Center Ossipee, New Hampshire. He died on June 15, 1955, at his home, at age sixty-six.

H. L. Mencken said of poet John V. A. Weaver, who went to Hollywood in the Twenties, “His adventures there were full of the frustrations and disgusts that all other writers of any sense encounter. The movie moguls were never able to fathom so direct and candid, not to say tactless [a] man: they were used to much smoother and more politic fellows.” Weaver had success with his free verse and moderate success with his novels, but Hollywood wanted him because he wrote “common speech” dialogue when talkies replaced the silents.

In the Thirties, Weaver was a fish out of water in Los Angeles. According to Mencken, “he liked the work, but in the end the malignant imbecility of the moguls wore him out.” Weaver’s 1924 marriage to Peggy Wood lasted, but they had frequent and lengthy separations. It’s unclear when Weaver revealed that he had tuberculosis. When he went west, the condition worsened. In early 1938, his doctors sent him to Colorado Springs to recover while Wood was appearing in Noël Coward’s Operette in London.

Weaver died on June 14, 1938, a month shy of turning forty-five. Five weeks later, Wood arrived in New York aboard the Queen Mary. At the dock she told the gathered reporters that she would honor her late husband’s wishes expressed in “When I’m All Through.” The four parts would be spread on a hill near their home in Stamford, a sunny field near South Stamford, and the ocean spot in Santa Monica, where they had shared happy times together. For the last part, she needed a busy avenue. “When I do, no one will see me,” she said. “I will be alone.”

For almost sixty years, Peggy Wood was an acting dynamo. In the Fifties, she did a one-woman show at her husband’s alma mater, Hamilton College, in which she read his poetry and found it so thrilling that she took it on the road. She wrote two memoirs and numerous magazine articles about acting, but it was her last feature role that ensured her cinematic immortality. She costarred in The Sound of Music in 1965 as Mother Abbess. Another actress sang for her because she was seventy-two years old at the time, but she received an Oscar nomination for best supporting actress. Her last stage role came in 1967 in Westport, Connecticut, alongside Ethel Barrymore Colt in A Madrigal of Shakespeare. She visited Marc Connelly and Margalo Gillmore at the Algonquin in 1968 and told a reporter she wouldn’t retire. “I have no idle hours. I’m in the theater.”

In the early Seventies, Wood moved to a retirement home in Stamford. On March 18, 1978, she died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Stamford Hospital. She was eighty-six years old. Her memorial service, organized in part by Connelly, was held at the Little Church around the Corner at 1 East 29th Street. After Wood’s death, her large collection of books was donated to a local library, which discovered that many were rare autographed first editions from the most famous writers of the twentieth century.

Alexander Woollcott’s last several years weren’t pleasant. He suffered constant pain from various ailments stemming from a lifetime of rich food and cigarettes. In 1930, his career revived when he joined CBS to host The Town Crier talk show, earning him $3,500 a week during the Depression, about $47,500 today. Woollcott divided his time between Manhattan for work and his lake house in Vermont for leisure. When World War II began, he took part in war bond drives with Dorothy Parker.

Woollcott had a serious falling-out with Ross, though, and the break was permanent. Ross had agreed that Wolcott Gibbs could write a multipart profile on Woollcott. Generally the rotund ex-critic didn’t mind what people wrote about him, but he was unhappy with parts of it, and sent Ross a blistering note that ended their friendship, which had begun in the Stars and Stripes office in 1918. They never made peace.

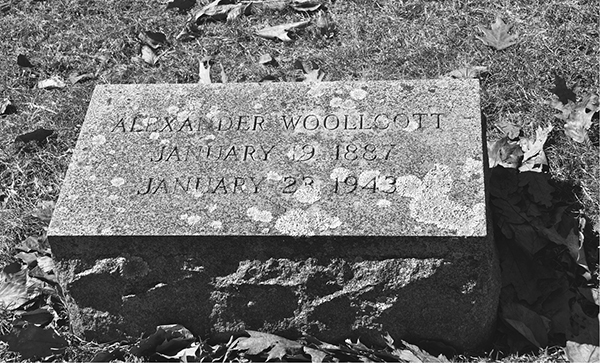

On January 23, 1943, a few days after he turned fifty-six, Woollcott suffered a stroke during a live panel discussion. He was carried out of the CBS studios in his chair and brought to Roosevelt Hospital, but it was too late. A week later, a memorial service was held at Columbia University’s McMillan Academy Theatre. Some two hundred mourners—including most of the living Round Table members—braved a snowstorm to journey to Morningside Heights to attend the brief tribute. Paul Robeson read Psalm 23, and Ruth Gordon gave a stirring eulogy. Following the program, several of the old friends met at the Algonquin, including Connelly, the Kaufmans, Leech, Marx, McMein, Parker, Ross, Sullivan, and Wood. Their enthusiasm waned without Woollcott’s presence.

After a mix-up, Woollcott ended up at his alma mater, Hamilton College. ◆ ◆ ◆

His remains were cremated, and a mix-up worthy of the Marx Brothers ensued. First, they were delivered incorrectly to his house on Lake Bomoseen, in Vermont. From there they were supposed to go to his alma mater in Clinton, New York, but they went to Hamilton, New York—home to Colgate University—thirty miles away. The ashes were sent from Colgate to Hamilton College, with a shipping charge of 67 cents due on receipt. Woollcott is interred in the Hamilton College cemetery not far from the campus theater. In 2000 the former Theta Delta Chi house was dedicated as the Alexander Woollcott House, and is now student housing.

One of the best places to live on the Hamilton campus is Woollcott House. ◆ ◆ ◆

The Legacy

Nearly a hundred years after the Algonquin Round Table first started meeting, not a day goes by that today’s media doesn’t mention one of these thirty names—a backstabbing joke on a TV sitcom, a tired wisecrack used by a lazy sportswriter, or a reference point to anoint a new Kaufman, the new Parker, or someone as funny as Benchley. The Vicious Circle exerted its influence on its own era, but also on the generations that have followed. “As I got older, I resolved that I would one day try to write comedies for the theater,” said Woody Allen, “and George S. Kaufman became an immediate role model.” Maureen Dowd modeled herself on Dorothy Parker, her favorite New Yorker. Awards and scholarships commemorate many of the group: the Robert Benchley Society Award for humor writing, the John V. A. Weaver Award at Hamilton, an ASCAP writing award named for Deems Taylor, and the Heywood Broun Prize from the Newspaper Guild.

Ferber, Marx, McMein, and Parker all made it onto commemorative US postage stamps. Scores of books, TV shows, movies, songs, and plays have explored their lives and work. The films they created have gone into the Library of Congress to be preserved for all time. Screenwriting students look on Mankiewicz as a god, his script for Citizen Kane analyzed to the last comma. Every summer, Ferber’s glorious Giant is playing on a drive-in movie screen somewhere in Texas, and a summer stock production of Show Boat is hitting the boards. The Portable Dorothy Parker has never gone out of print since the day Viking Press published it 1944.

Much of what F.P.A. wrote was ephemeral, but he did leave behind his Diary, now a goldmine of source material for researchers, and “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon” made it into Cooperstown with the ballplayers it immortalized. Ross left behind a magazine that has become one of the most influential in the nation’s history. Without it, we would have had no Addams Family, The Lottery, Silent Spring, Brokeback Mountain, or a thousand other cultural gems.

The Round Table came into existence when all points converged in one spot, in a perfect confluence of creativity, friendships, professional courtesy, and camaraderie. None of them really knew that their high-flying habits would mark them as legends for the rest of their lives. “I never have encountered a more hard-bitten crew,” Ferber wrote in 1938. “But if they liked what you had done they did say so, publicly and whole-heartedly. Their standards were high, the vocabulary fluent, fresh, astringent and tough. Theirs was a tonic influence, one on the other, and all on the world of American letters.” New York became a better place for their gatherings, its cultural landscape blessed with almost a century of influence after their time spent together in a hotel dining room.

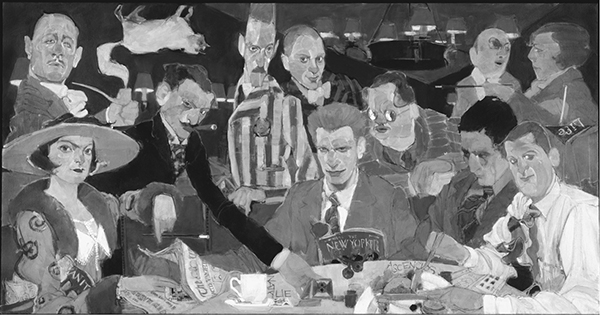

On the centennial of the Algonquin Hotel, in 2002, Natalie Ascencios was commissioned to create a new painting of the core group of the Round Table members. She chose, from left: Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Robert E. Sherwood, Harpo Marx, Harold Ross, Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, and Heywood Broun. In the top right are playwrights Marc Connelly and Edna Ferber. The painting is the focal point of the Round Table Room and is near the spot where the friends gathered in the 1920s. ◆ ◆ ◆