CHAPTER 10

IN STUDYING WORDS, I have frequently been asked to analyze language to answer questions that I would have never considered. Lawyers, historians, music lovers, political consultants, educators, intelligence agents, and others have occasionally contacted me to see if our language approach could give them a different perspective on a problem they have been thinking about.

This chapter brings together some of the more interesting projects my students and I have been playing with over the years. The topics vary quite a bit. Nevertheless, they showcase different ways words can be analyzed to answer novel questions.

USING WORDS TO IDENTIFY AUTHORS

The phone call I received from the senior partner in a law firm caught me off guard. He was curious if I could analyze an e-mail that had been sent to a member of his firm; let’s call her Ms. Livingston. It was quite sensitive, he confided, and it was important that he talk directly with the person who had sent the e-mail. The only problem was that the e-mail had been sent anonymously from an untraceable e-mail address. After I agreed to look at it, he sent me the following e-mail:

Ms. Livingston:

I think you should know that David Simpson has perpetuated the idea that you have no credibility among your colleagues. He says you altered depositions and falsified expense reports at your last job in New York. He says this is the reason you left so abruptly.

He has spread these stories to people in various departments, including Billing, Personnel, Public Relations and to those at the executive level. It is uncertain how and when our senior partners will deal with this. But if you start getting the cold shoulder, you will know why.

When I first heard of this, I was surprised, but took what he said at face value. Of course, this was before I learned of his voracious appetite for propagating half-truths, gossip, and outright lies, all in the name of somehow making himself look knowledgeable and “better.”

Such a pity. He obviously has talent, but it is all negated by his vile, malicious tongue. All I can think of is a tremendous sense of insecurity. But I digress. I just thought you would like to know.

A friend

After receiving the e-mail, Ms. Livingston turned it over to the law firm. She dismissed the rumor as provably false but was concerned that if David Simpson really was spreading false rumors, it could damage her reputation along with that of the firm. I had spent several years developing methods to analyze language and personality but had never been paid to be a word detective.

What kind of person may have written the note? Is “A friend” a male or female and what is his or her approximate age? What is the person’s link to Ms. Livingston, to David Simpson, and to the firm? Any hints as to the person’s personality traits?

In the years since I worked on the case, several new ways of looking at words have been developed. One involves comparing the words “A friend” used with those of tens of thousands of regular bloggers. For example, by looking at just the function and emotion words, we can guess that there is a 71 percent chance that the author is female and a 75 percent chance that she is between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five. It is much harder to get a good read on her personality. One analysis suggests that there is a fairly good chance that the author of the e-mail is high in the trait of narcissism—meaning she may be somewhat conceited and manipulative.

Look more closely at the e-mail and other hints emerge. The person is psychologically connected to the firm (“our senior partners”) and has knowledge of rumors from across several departments within the firm. The person also is working to impress Ms. Livingston by using a large vocabulary. Particularly interesting is the use of words and phrases such as “voracious appetite,” “vile,” and “malicious tongue.” These are Old Testament words that, in other analyses, were primarily used by people between forty-two and forty-four years of age at the time of the project.

One other important clue was the layout and punctuation. The e-mail was professionally typed with paragraphs of equivalent size. There was only one space between the period and the beginning of the next sentence, which suggests the person learned to type after about 1985—when desktop computers became popular—or the person had some background in journalism or publishing before 1985, where the single space after a period was the norm. (My wife, who was in publishing before 1985, explained this to me.)

What happened? When I submitted my report to the senior partner, he was relieved because it precisely matched the person he had suspected—a conscientious women in her early forties with a background in newspapers who had been with the firm for several years. I never learned the final disposition of the case, but I see that Ms. Livingston is now a senior partner with the firm.

WHO WROTE IT? THE ART OF AUTHOR IDENTIFICATION

Deciphering linguistic clues to solve crimes has a rich tradition in criminology. The FBI, various national security agencies, and local police departments around the world occasionally seek the expertise of linguists to help decode ransom notes or written threats, or to assess who might have written legal or other documents.

One of the best-known early forensic linguists is Donald Foster, a professor of English at Vassar College. Using a mixture of computer and deductive skills, along with a broad knowledge of history and literature, Foster has worked with law enforcement agencies on high-profile cases such as the Unabomber, the 2001 anthrax attacks, and the 1997 JonBenét Ramsey murder case. He has also applied his methods to determine the authenticity of some works by Shakespeare and others. Perhaps his most successful venture was in identifying Joe Klein as the author of an anonymously published satirical novel on the Clinton presidency, Primary Colors.

Foster has been a controversial figure because several of his high-profile claims about authorship have not panned out. He has also been less than forthcoming about the details of his methods of author identification, something that reflects his training in English rather than statistics and science. Nevertheless, Foster’s approach has alerted the literary and forensic worlds to the promise of computer-based methods to identify authors and their work.

FINDING THE TELLS

World-class poker players closely watch and listen to their opponents in attempts to predict the cards they may be holding. Often players will pretend they have a poor set of cards when they have a good set; other times they will bluff by giving the impression they have a winning hand when they don’t. Experts look for telling signs of deception—or “tells.” Some players avoid looking around the table, others tap their feet, yet others talk more loudly. The ability to decipher tells can give card players a large advantage in high-stakes poker games.

There are various types of tells in people’s use of written language as well. Two are particularly good clues in identifying authors: function words and punctuation. This can be seen in looking back at the blogs we collected in 2001 as part of the September 11 project discussed in the last chapter. Recall that we saved about seventy blog entries from each of a thousand people in the two months before and after the 9/11 attacks. Every few years, my students and I revisit LiveJournal.com to see if the same people are still posting. Ten years later, 25 to 30 percent are still active. About 25 percent have erased their accounts. The remainder stopped posting, on average, five years after the attacks, in 2006. Many of the former posters migrated to other systems such as Facebook or Twitter.

Simply reading the last ten years of people’s posts provides an intimate picture of their lives. Not unlike Michael Apted’s Seven Up! documentary series, we have been able to track the unfolding experiences of the bloggers as they grow older. Many of the same issues still drive the authors. Even though some have now married, had children, and started careers, recurring insecurities, motives, and goals keep returning. Those who were happy and upbeat in 2001 tend to be the same optimistic people nine years later. For example, a young father writes in a random blog in 2001 about his favorite hockey team:

lucky lucky chicken bone. i shall do the happy-cup-dance. we shall win. we shall triumph. and there will be much rejoicing! i just need to get cable first. ok. i wasn’t just gonna post about hockey, but yvonne’s ready to go. yeah. shut up. you try resisting that sweet, sweet candeh.

And nine years later, you see the same person:

My first attempt at making salsa was, in my humble opinion, not too shabby. protip: don’t use Roma tomatoes. I’m not sure why the hell I thought they’d work out fine, but I was terribly wrong. Ok, not terribly just mildly. ah, salsa humor. I’m heading back to the mexi-mart today to pick up the goods to try another batch. Maybe i’ll have it done in time for the bbq. Who knows? Since my catharsis, I’ve been in an amazing headspace.

Obviously, these two writing samples are from the same person. I mean, anyone could spot it immediately.

Really?

Actually, we can see the similarities once we know that they were written by the same person. But what if we read blogs all day and came across the second one several hours after reading the first? In all likelihood, most people wouldn’t jump up yelling, “Aha! I have read that writing style earlier … yes, from the guy who wrote about hockey.” Could language experts or computers make a definitive match? Are language fingerprints as reliable as DNA or real fingerprints? The short answer is no. However, computerized language analyses do a reasonably good job at matching which writing goes with which person.

Imagine we had a large number of blog entries from twenty bloggers. Several years later, we retrieve a handful of new postings from each of the same twenty bloggers. Now imagine sitting on your living room floor with hundreds of pages of posts trying to match each current blog entry with the original posts of the twenty bloggers. All things being equal, anyone should be able to match 5 percent of the blog posts correctly just due to chance alone. Most people would do terribly on this task. It is unlikely that you would match at rates any better than 10–12 percent. The writing style differences are too subtle and there is just too much information.

Computers are more patient and systematic. If we just analyze function words, the computer correctly matches the recent blog posts with the original authors about 29 percent of the time. This is actually impressive given the time lag between the writing of the posts.

But there is more to author identification than function words. Look at the consistency of punctuation. The following woman, for example, continues to use asterisks in the same way nine years apart. This was part of an early 2001 entry:

Oh.. I have also discovered a shy streak I didn’t know I had. I guess you would call it shyness. Somebody made me *blush*. Repeatedly. That is *weird*. I don’t blush.

And in 2010:

We *are* in post-post-punk now, aren’t we? The guys in the band made a joke about how they just wrote that song yesterday, and maybe a quarter of the people in the room didn’t get why the rest of us were chuckling. weird. *shrug*

Others use punctuation in equally unique but more subtle ways. From a twenty-seven-year-old male in 2001:

I mailed memorial gift checks to Immanuel [endowment donation in honor of Joan’s mother]; and St Anne’s - for my favorite accounting professor the Smythe scholarship. Frank & Rebecca brought over “Midnight in the Garden of Good & Evil” and a couple homebrews. My eyelids want to close so I better …

In 2010:

I didn’t quite know what to say thinking, “hmm, mud, what is it … when I found a mirror I didn’t see any other “brown stuff” i brought a watermelon and Costco multi-grain chips, Had a couple beers, I took Yuengling B & T - dinner was boiled/grilled chicken, okra, slaw, “dipping” brownies.

This person is the Alvin Ailey of punctuation. He jumps, swirls, swoops, and rolls with the full gamut of punctuational possibilities: [ ; - … & “/. Oddly, when I first read his blog, I didn’t even notice his use of punctuation marks—they just blended into his writing. However, when his blogs were computer analyzed, his use of punctuation stood out.

Punctuation marks can identify some people better than anything they write. In fact, when looking only at punctuation, computer programs identified 31 percent of authors correctly—essentially the same rate as relying on function words. When both function words and punctuation were used together, the computer correctly paired the original bloggers with writing samples several years later 39 percent of the time.

Punctuation, function words, and content words that are used in everyday writing are all parts of our personal signature. To appreciate this, go to your own e-mail account and spend a few minutes looking at the e-mails you send to and receive from others. Start with the page layout. Some people tend to write very long e-mails, whereas others keep them to a sentence or two. People tend to differ in the length of their paragraphs and sentences. Their greetings and closings vary tremendously as well. Some use emoticons; some never do.

Some of these differences may be psychologically important but most probably aren’t. The person who ends most e-mails with “Sincerely” may do this just because they were told to do so when they were younger. Even though these variations may not say anything about your conflicts with your mother when you were an infant, they still mark you. That is, they are part of your general writing style that makes you stand out from everyone else. And that is the interesting story. All of the language features we can measure can help to identify you.

THE CASE OF THE FEDERALIST PAPERS

In 1787 and 1788, a series of eighty-five essays were published in pamphlets and newspapers across the American colonies in an attempt to sway people to support the proposed document that would become the U.S. Constitution. Published anonymously under the name Publius, the papers discussed a wide range of topics, including the role of the presidency, taxation, state versus federal power, etc. Even at the time, many knew that Publius was not a single person but, instead, James Madison (who would become the fourth president), Alexander Hamilton (the first secretary of the treasury), and John Jay (the first chief justice of the Supreme Court).

In the years that followed, the authorship of seventy-four of the essays gradually became known. Madison wrote fifteen, Hamilton fifty-one, Jay five, and Madison and Hamilton jointly wrote three of the articles. The authorship of the remaining eleven was never determined and has been a source of speculation ever since. The first serious attempt to identify the author of the eleven papers was undertaken by historian Douglass Adair as part of his dissertation in 1943. Adair’s historical analysis deduced that all eleven anonymous essays had been written by James Madison.

The debate resurfaced in 1964 when statisticians Frederick Mosteller and David Wallace introduced a new way to analyze words. By focusing on a small number of function words, they concluded that Adair was indeed correct because their elegant statistical models pointed to Madison as the likely author. Since then, identifying the anonymous authors of the Federalist Papers has become something of a sport whenever new language analysis methods are developed.

I am proud to announce the New Official Findings. Historians, prepare your quills.

Function Word Analyses

Using similar methods to those of Mosteller and Wallace, we find the same effects. The anonymous eleven cases all use pronouns, prepositions, and other stealth words in ways similar to James Madison. Case closed?

Not so fast. Other statisticians have discovered a small problem that exists with the investigation of our founding fathers’ function words. Since Mosteller and Wallace, another technique has been devised that is called cross-validation. The idea is to examine each of the original essays individually as if they were anonymously written. In other words, we pull one of the known essays out of the stack and then develop a computer model based on the remaining essays to try to determine who wrote the essay we pulled out. It’s a marvelous method because we are determining results about a question whose answer we already know. If our cross-validation analyses successfully guess who wrote all of the known essay writers, we can place a tremendous amount of trust in our research methods.

Heartbreak city. The cross-validation results suggest that Mosteller and Wallace might have been wrong. About 14 percent of the known essays are not classified correctly based on function words. This is a serious problem. If the computer can’t tell us what we already know with extremely high accuracy, we have to be careful in interpreting the results from essays about which we don’t know the author.

Punctuation Analyses

Recall that people’s use of punctuation can reveal authorship in many cases. Using similar cross-validation analyses on punctuation resulted in disappointing results as well. And using a combination of function words and punctuation to predict authorship produced slightly better results than the function words alone. Interestingly, the function words plus punctuation results hinted that Hamilton wrote three of the eleven anonymous essays.

Going for the Tell: People’s Use of Obscure Words

Over the course of my career I have written more papers than I care to admit. Perhaps ten years ago, a colleague thanked me for a review I had written about her research. I was flattered, of course, but a bit puzzled since my review had been written anonymously. “How did you know I was the author of that review?” I blurted out. She just laughed and said one word: intriguing.

Intriguing, indeed. I went back to many of my reviews, then articles, and even books. I was shocked by how frequently I used the word intriguing. Even this book is littered with intrigue—I just can’t help myself. Over the years, I’ve noticed that most of my colleagues and friends have their own favorite but relatively obscure words that even they aren’t familiar with. The words aren’t used at high rates but they find their ways into the occasional e-mail, Facebook post, blog, tweet, or article.

Did Madison or Hamilton have tell words in their articles? With a little sleuthing it turns out the answer is yes. In almost half of his papers, Hamilton used the word readily; Madison never did. In nine of his fifteen articles, Madison used consequently, compared with Hamilton’s use of the word three times across his fifty-one papers. Hamilton also had a fondness for commonly, enough, intended, kind, and naturally. Madison tended to overuse absolutely, administer, betray, composing, compass, innovation, lies, proceedings, and wish.

If we just examine the use of these fourteen words, the statistics are promising—almost a perfect score for cross-validation. However, the story for the unknown authors comes out quite differently than what the earlier scholars claimed. They suggest that Hamilton actually wrote eight of the anonymous essays and Madison wrote only three.

What is truth in this case? Reading Douglass Adair’s delightful account of the controversy surrounding the eleven articles, it is clear that Hamilton and Madison had very different memories of who wrote what. Adair is ultimately more sympathetic to Madison’s claims, although the objective evidence to assign authorship is not compelling either way. Like Mosteller and Wallace, I have no in-depth knowledge of the actual case. Nevertheless, historians should know that from a statistical perspective, the case is still open.

WHAT SONG LYRICS SAY ABOUT THE BAND: THE BEATLES

The Beatles were together for about ten years before breaking up in 1970. During their time together, they recorded over two hundred songs and influenced music, politics, fashion, and culture for the next generation. The lead songwriters, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, together or separately wrote 155 songs, and George Harrison penned another 25. Even today, scholars—and the occasional barfly—debate about the relative creativity of the band members, who ultimately influenced whom, and how the band changed over time.

Most of this book is devoted to the words people generate in conversations or write in the form of essays, letters, or electronic media such as blogs, e-mails, etc. Music lyrics, however, tell their own stories about their authors. My good friend and occasional collaborator from New Zealand, Keith Petrie, suggested that a computerized linguistic analysis of the Beatles was long overdue. Once we realized how complicated the topic really was, we invited another music lover and psychologist from Norway, Borge Silvertsen, to join us. What could we learn about the Beatles by analyzing their lyrics? Quite a bit, it turns out.

In many ways, the lyrics of the band reflected the natural aging process one usually sees in all working groups. Recall from the last chapter that as working groups spend time together, their conversations evidence drops in I-words and increases in we-words, with increasing language complexity, including bigger words and more prepositions, articles, and conjunctions. As the group aged together, the Beatles expressed themselves through their lyrics in the same way any group would in their conversations with each other.

In their first four years together, their songs brimmed with optimism, anger, and sexuality. Their thinking was simple, self-absorbed, and very much in the here and now. In the last years of the band, the group’s lyrics became more complex, more psychologically distant, and far less positive. Particularly telling was the drop in the use of I-words from almost 14 percent during their first years together to only 7 percent in their last three years. Lyrics also provide a window into the personalities of the various songwriters within a group. Although John Lennon and Paul McCartney had an agreement that all of their songs would include both men as authors, the order of authorship and extensive interviews has provided historians with a solid, albeit not perfect, record about who wrote what. Between the two, Lennon is credited as the primary writer for seventy-eight songs, McCartney for sixty-seven, and another fifteen songs are considered true collaborations where both were closely involved in the lyrics.

In the popular press, John Lennon was generally portrayed as the creative intellectual and McCartney as the melodic, upbeat tunesmith. The analyses of their lyrics paint a different picture. Lennon did use slightly more negative emotion words in his songs than McCartney, but the two were virtually identical in their use of positive emotions, linguistic complexity, and self-reflection. Interestingly, McCartney’s songs more often focused on couples—as can be seen in his higher use of we-words—than did Lennon’s.

Who was the more creative or varied in his lyric-writing abilities? We can actually test this by seeing how the lyrics from different songs are mathematically similar—both in terms of content as well as linguistic style. Whereas the popular press usually assumed that Lennon was the creative and stylistically variable writer, the numbers clearly support McCartney. Across his career as a Beatle, Paul McCartney proved to be far more flexible and varied both in terms of his writing style and also in the content of his lyrics.

And let’s not forget George Harrison, the quiet, spiritual Beatle who wrote about twenty-five songs, especially in the last years of the Beatles. Although somewhat more cognitively complex in his words than either McCartney or Lennon, he was the least flexible in his writing. In other words, both the content and style of his lyrics were more predictable from song to song. These same types of analyses also demonstrated that Harrison was more influenced in his songwriting style by Lennon than by McCartney.

DOES COLLABORATION RESULT IN AVERAGE OR SYNERGISTIC RESULTS?

Collaborations between writers is a funny business. When two people work together, in John Lennon’s words, “eyeball to eyeball,” do they produce something that is the average of their usual styles or is the result something completely different than either could have written alone? Language analyses can answer this question for both the Beatles and the Federalist Papers. Recall that Lennon and McCartney had very close collaborations on 15 of their 160 songs. Alexander Hamilton and James Madison jointly wrote three Federalist Papers.

Across the various dimensions of language and even punctuation, we can calculate what percentage of the time the collaboration produces an effect that is the average of the two collaborators working on their own. There are three clear hypotheses:

• Just-like-another-member-of-the-team hypothesis. Collaborative writing projects produce language that is similar to that produced by a single person writing alone. Sometimes the work will use words like one author and other times like the other author.

• The average-person hypothesis. More interesting is that collaborations produce language that is the average of the two writers. If Lennon uses a low rate of we-words and McCartney uses a high rate, it would follow that their collaboration would produce a moderate number of we-words.

• The synergy hypothesis. Even more interesting is the idea that when two people work closely together, they create a product unlike either of them would on their own. Their language style will be distinctive in a way such that most people would not recognize who the author was. Wouldn’t it be great if the results supported this hypothesis? Come on, statistics, please, please me.

And the winner by a mile is, in fact, the synergy hypothesis. When Lennon and McCartney and when Madison and Hamilton were working together, they produced works that were strikingly different than works produced by the individual writers themselves. When collaborating, the Lennon-McCartney team produced lyrics that were much more positive, while using more I-words, fewer we-words, and much shorter words than either artist normally used on his own. Similarly, when Hamilton and Madison worked together they used much bigger words, more past tense, and fewer auxiliary verbs than either did on their own. In fact, across about seventy-five dimensions of language and punctuation, more than 90 percent of the time collaborations resulted in language that was either higher or lower than the language of the two writers on their own.

Note that collaborations produce quite different language patterns than what the individuals would naturally do on their own. What’s not yet known is if collaborative work is generally better than individual products. This is a research question that is begging to be answered.

SUMMING UP: PACKING YOUR AUTHOR IDENTIFICATION TOOL KIT

Author identification is becoming a very hot topic in the computer world. The three methods that we have relied on involve tracking the rate of function word usage, analyzing punctuation and layout, and examining the use of obscure words. Each of these methods does far better than chance in identifying characteristics of an author as well as matching the author’s writing to other writing samples.

In terms of understanding the author’s personality, we currently know the most about function words. As discussed throughout the book, pronouns, articles, and other stealth words have reliably been linked to the authors’ age, sex, social class, personality, and social connections. Less is currently known about punctuation and personality, but I suspect future research will begin demonstrating convincing links. After all, it’s hard to imagine that there isn’t a difference between the writer who writes at the end of his or her note, “Thanks.” versus one who writes, “Thanks!!!!!!!!!”

The least is known about the use of relatively obscure words and their link to personality. If one author uses intriguing and another remarkable, does the choice of the word itself say anything about the person?

There are also a number of other exciting methods being developed by labs around the world that are relevant to author identification. One strategy is to look at something called N-grams. These can be pairs of words (or bigrams), three words in a row (or trigrams), etc. Looking at the beginning of this paragraph, the bigram approach would look at the occurrence of “there are,” “are also,” “also a,” and so forth. The idea is that some people naturally use groups of words together in a unique way that identifies who they are.

More elaborate strategies attempt to mathematically predict word order within sentences based on the words the writer has already used. In the beginning of the last paragraph, the odds that it would start with the word there might be 1 in 1,000. The odds that the word are would be the second word, knowing that the first word is there, is perhaps 1 in 20. Knowing “There are,” the odds that the third word is also … you can get the idea. Researchers can determine how unique a person’s writing is and how much it deviates from chance on a sentence-by-sentence level. One argument is that every person’s way of stringing words together is unique to them. Yet another linguistic fingerprint idea.

Other new methods examine parts of speech, syntax, cohesiveness of sentences and paragraphs—all using increasingly sophisticated mathematical solutions. The time is not too far away where the author of most any extended language sample will be identifiable.

WORDS AS CLUES TO POLITICAL AND HISTORICAL EVENTS

It comes as no news to historians and literary scholars that the primary key to understanding people or works of the past is the study of the written word. Most scholars, however, rely primarily on their own reading of historical works rather than computerized text analyses. This has been changing over the last few years. One area that has been particularly innovative is political science. Partly because of the availability of transcribed speeches, interviews, newspaper and online articles, newscasts, and even letters to the editor, researchers have been able to tap the appeal of political candidates and people’s responses to them.

One of the pioneers in the field, Roderick Hart, has published a series of groundbreaking books and articles that help explain how the results of important historical elections—such as the race between Bill Clinton and Bob Dole—were presaged by the ways the candidates used words in their speeches. He also collected hundreds of letters to the editors in newspapers across the United States and was able to track the perceptions of voters. Extending Hart’s work, we can begin to reinterpret historical events by analyzing the words of all the historical players who leave behind trails of words.

WHO ARE THESE PEOPLE? TRYING TO FIGURE OUT U.S. PRESIDENTS

Watch any news source—television, Internet, newspaper, magazine—and much of the coverage is devoted to understanding the thinking of the current, future, and past presidents. If it’s the middle of an election cycle, pundits make predictions about how each of the candidates would perform if elected. If a president has recently been elected or reelected, we want to know what he or she will try to accomplish in the months and years ahead. And even after the president has stepped down, pundits continue to ask, “What was he thinking? Why did he do that?”

In one of the most impressive books on the psychology of politics, The Political Brain, researcher Drew Westen argues that the most successful politicians are the ones who can emotionally connect with the electorate. Logic, intelligence, and reason are certainly very fine qualities but when the voter enters the ballot box, it is the social and emotional dimensions of the campaign that usually drive the election.

We resonate with people who seem to be attentive and respectful to others and, at the same time, exhibit their emotions in a genuine way. Social-emotional styles can be detected through body language, tone of voice, and, of course, words. For presidents and presidential candidates, we have ample opportunity to evaluate social-emotional style through speeches, interviews, pictures, and videos of their interacting with their families and others. From a language perspective, presidents leave a stream of words like no other humans.

A fairly simple way to measure social-emotional styles is to count how often personal pronouns and emotion words are used. As a general rule, people who are self-reflective and who are interested in others will use all types of personal pronouns at high rates—including I, we, you, she, and they. Similarly, people are viewed as more emotionally present if they use emotion words—both positive and negative—than if they don’t. By analyzing pronouns and emotion words in the speeches of presidents, we can begin to get a sense of their general social-emotional tone.

At most, U.S. presidents give inaugural addresses once every four years. However, most submit a State of the Union message to Congress every year that they are in office. State of the Union messages began with George Washington in 1790. Although Washington and John Adams presented the message in speeches to Congress, Thomas Jefferson changed the tradition by simply submitting a written version. In 1913, Woodrow Wilson reinstated the spoken State of the Union message. However, from 1924 until 1932, the messages returned to written format. Beginning with the inauguration of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (or FDR) in 1933 and up to today, virtually all States of the Union have been presented in speech format to Congress. Despite these variations in presentation style, it is fascinating to see how the emotional tones of the messages have changed from president to president.

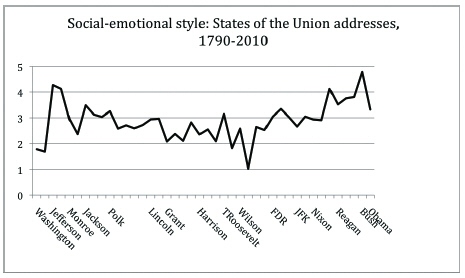

As you can see in the graph, several presidents were far more social-emotional than their predecessors. Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Theodore Roosevelt, Jimmy Carter, and George W. Bush used particularly high levels of personal pronouns and emotion words. James Monroe, Warren Harding, and Barack Obama all evidence significantly lower social-emotional ratings than those before them. In fact, it is interesting to see that George W. Bush is unquestionably the most social-emotional president in the history of the office and that Obama is currently the lowest since Richard Nixon.

Rate of social-emotional language by U.S. presidents in their annual State of the Union messages delivered to Congress. The numbers have been adjusted to control for written versus spoken presentations.

A State of the Union address is essentially a formal speech that could, in theory, be written by anyone. Its tone may reflect that of the president’s administration but it doesn’t necessarily tell us about the psychological makeup of the president. Fortunately, a more natural source of a president’s language now exists thanks to the popularity of press conferences. Beginning with FDR, press conferences evolved into freewheeling interactions between the press and president that were transcribed and saved.

From a psychologist’s perspective, press conferences are glorious. The members of the press variously try to cajole, befriend, challenge, and sometimes outrage the president. The press-president relationship is further complicated because both the press and the president desperately need each other to accomplish their somewhat different goals. Most important, interactions with the press are generally unscripted and allow us to monitor the presidents’ thoughts and emotions through the use of words.

Most presidents have only a small number of formal press conferences every year—usually between four and ten—more if there is a national crisis, fewer if they are being publically ridiculed or impeached. In addition to the formal press conferences, presidents often will talk with reporters on random occasions such as after introducing a foreign dignitary or while waiting for their car. Because most meetings with the press are recorded and transcribed, there are usually dozens of natural-language samples available for most presidents since the 1930s.

Interestingly, the ways presidents talk with the press are linguistically quite similar to their State of the Union addresses. As with his State of the Union speeches, George W. Bush emerges as the president whose language is the most social-emotional in press conferences. Since FDR, Nixon has been the lowest by far.

What about Ronald Reagan? Many people consider Reagan one of the most socially adept presidents since FDR. In both speeches and press conferences, Reagan’s use of personal and emotional language was always around the average. From the outside, he seemed like a social-emotional person—perhaps a bit like George W. Bush. Closer analyses of Reagan’s language suggest that this may be an illusion. Reagan, it seems, stands out more as a storyteller than a social-emotional leader. Recall from earlier chapters that stories or narratives require the use of social words together with past-tense verbs. Combining these two dimensions, Reagan’s score on storytelling is far and away higher than any other modern president’s.

The Ronald Reagan findings provide a little more insight into the different personalities of presumably sociable or personable people. No matter what their politics, most people who spent any time with George W. Bush felt that he was socially engaged. In social gatherings, he was genuinely interested in other people and readily expressed his own emotions. Whether accurately or not, most walked away with a sense of knowing him.

The biographies of Reagan paint a very different picture. Indeed, Reagan’s official biographer, Edmund Morris, eventually gave up on a traditional biography because he couldn’t get Reagan to open up in a personal or emotional way about himself. Reagan loved to tell stories of all kinds, but according to Morris, he had a “benign lack of interest in individual human beings.” After working on an in-depth two-part television series on Reagan in 1998, the series editor Adriana Bosch reported, “Reagan was not a man given to introspection … As his son Ron told us, ‘No one ever figured him out, and he never figured himself out.’ ”

Although outsiders may naively think that Bush and Reagan were social-emotional men, the language findings help to burrow under these impressions.

WHAT IS I SAYING?: THE MISSING PRONOUNS OF BARACK OBAMA

One hopes that you have been taking notes in reading this book. If you have, please refer to the many ways that the first-person singular pronoun I is used. Maybe you have skipped or forgotten these earlier chapters but feel as though you can take the Advanced Placement Test on I-word usage. And you can. Please go to the following website and take the one-minute I exam: www.SecretLifeOfPronouns.com/itest. It might be a good idea for those who have taken notes to do so as well.

The ten-item I-test has now been completed by well over two thousand people and demonstrates that very few people know who uses the word I. In fact, Ph.D.s in linguistics do about the same on the test as high school graduates, averaging around five correct answers out of ten. If you didn’t do well on the exam, you are in very good company.

The word I is the prototypical stealth word. It is the most commonly used word in spoken English and we rarely register it when it is used by us or other people. Because people think that I-words must reflect self-confidence or arrogance, they assume that people who are self-confident must use I-words all the time.

Obama is a perfect case study. Within days of his election in 2008, pundits—especially those who didn’t support him—started noting that he used the word I all the time. Various media outlets reported that Obama’s press conferences, speeches, and informal interviews were teeming with I-words. A long list of noteworthy news analysts such as George Will, English scholars including Stanley Fish, and even occasional presidential speechwriters such as Peggy Noonan pointed out Obama’s incessant use of I-words. Some of their articles on the topic were published in highly respected outlets that usually have diligent fact-checkers—the Washington Post, the New York Times.

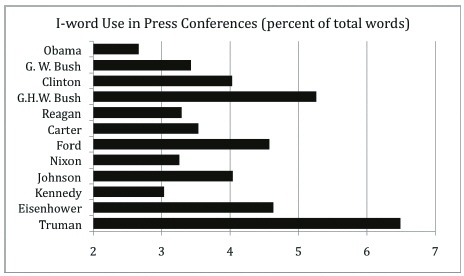

The only problem is that no one bothered to count Obama’s use of I-words or compare them with anyone else’s. As you can see in the graph on the next page, Obama has distinguished himself as the lowest I-word user of any of the modern presidents. Analyses of his speeches reveal the same pattern. When Obama talks, he tends to avoid pronouns in general and I-words in particular.

If Barack Obama uses fewer I-words than any president in memory, why do very smart people think just the opposite? The problem may lie in the ways we naturally process information. First, as we have found with the I-test, most people believe that those who are the most self-confident use I-words at much higher rates than insecure or humble people. If we think that someone is arrogant, our brains will be searching for evidence to confirm our beliefs. Whenever the presumed arrogant person uses the word I, our brains take note—ahhh, additional proof that the person is arrogant. It is not coincidental that the commentators who have crowed the loudest about Obama’s obnoxious use of I-words are people who do not share his political views.

Use of first-person singular pronouns in press conferences as a function of total words.

There is another story as well. Obama’s impressively low use of I-words says something about him: He is self-confident. In an interview on National Public Radio’s Weekend Edition on August 8, 2009, Dan Balz and Haynes Johnson were asked about their book, The Battle for America 2008: The Story of an Extraordinary Election. Looking back over his distinguished political reporting career studying presidents since Eisenhower, Johnson noted that Obama is “the single most self-confident of all the presidents” he had ever seen.

Obama’s use of pronouns supports Johnson’s view. Since his election, Obama has remained consistent in using relatively few I-words compared to other modern U.S. presidents. Contrary to pronouncements by media experts, Obama is neither “inordinately fond” of first-person singular pronouns (as George Will wrote) nor exhibiting “the full emergence of a note of … imperial possession” (to quote Stanley Fish). Instead, Obama’s language suggests self-assurance and, at the same time, an emotional distance.

AVERTING YOUR I’S FOR ATTACKS AND WARS

I-words track where people pay attention. If people are self-focused, insecure, or self-effacing, they tend to use first-person singular pronouns at high rates. If confident, focused on a task of some kind, or lying, their rates of using I-words drop. Rarely do we get samples of real-world spoken language from people on a daily basis over several years to be able to track fluctuations in their attentional focus and thinking patterns. Recent U.S. presidents, especially George W. Bush, have proven to be an exception. Unlike most of his predecessors, Bush met with the press an extraordinary number of times. During his first four-year term in office, at least 360 separate press conferences or press gatherings were transcribed and posted on the WhiteHouse.gov website. By analyzing his use of I-words in his answers to questions, we could determine how he was thinking in light of ongoing political and social events.

Bush’s presidency will likely be fodder for historical analyses for generations. The prodigal son of the forty-first president, he was generally thought to be a warm and charming man but without a clear vision of what he wanted to accomplish as president. Bush’s tenure as president was more tumultuous than most. Nine months into his presidency, operatives working with Osama bin Laden attacked the World Trade Center and Pentagon, killing over three thousand people. Less than a month later, on October 7, 2001, Bush directed an attack that toppled the government of Afghanistan in a futile hunt for bin Laden. In his most controversial act as president, Bush turned his sights on Iraq and, arguing that the country harbored weapons of mass destruction, launched a full-scale invasion in March 2003. No weapons of mass destruction were ever found and the United States and its allies continue the occupation of Iraq to this day. His second term in office, which will not be discussed here, also had its problems, including the destruction of New Orleans from Hurricane Katrina, the mounting turmoil in occupied Iraq, and the beginning of the global economic meltdown.

Overlaying the actions of Bush was his personality. Many considered him to be relatively transparent, sometimes exhibiting boyish delight, petulance, defensiveness, and compassion. In reading the transcripts of his press conferences, the different sides of his personality often emerge even when he was responding to a single question. No matter what your political persuasion, the transcripts reveal a man both warm and charming and, occasionally, arrogant and mean.

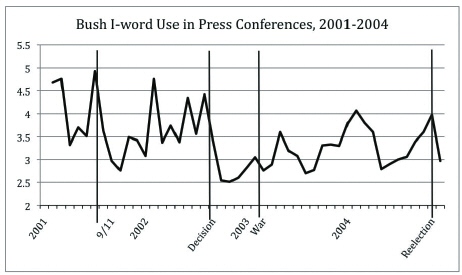

Three interconnected events defined his first term. The first was the 9/11 attacks. As noted in the last chapter, within a matter of days he went from being tolerated to being adored by the American population. The second defining event, which the world did not directly witness, was his decision to invade Iraq. And the third was the actual invasion in March 2003. The graph on the next page charts Bush’s use of I-words in his press conferences on a monthly basis. Each month, he typically spoke to the press six to eight times, uttering around a thousand words during each press conference. As is apparent, his use of I-words dropped during his first three months in office. In fact, this happens with most new presidents (although not Barack Obama). Starting the job is generally an intimidating experience that takes a few weeks to get used to.

The first dramatic drop in I-word use occurred immediately after the 9/11 attacks. Bush, like the majority of Americans, curtailed his use of I’s and increased in his use of we-words. The effect of the attacks on him was large, and over the next few months, his attention was focused on a number of pressing matters—the invasion of Afghanistan, the anthrax attacks, and attempting to reorient the government to deal with terrorism. You will note that after November 2001, his use of I-words gradually increases most months.

The second substantial drop in I-word usage occurred in mid-September 2002. According to White House scholars, the Bush administration had long been troubled by Iraq and its leader Saddam Hussein. In addition, some within the White House felt that Hussein was behind the September 11 attacks and/or was intent on building a nuclear arsenal. In June 2002, some in the Bush administration began to suggest a new approach to foreign policy. Part of the Bush Doctrine, as some referred to it, was that the United States was justified in preemptively attacking a country with hostile intent.

George W. Bush’s use of I-words across 360 press meetings during the first term of his presidency (based on percentage of total words). The vertical lines represent the following: 9/11 = September 11 attacks; Decision = probable final decision to go to war in Iraq (October 2002); War = invasion of Iraq (March 2003); Reelection = November 2004.

Through the summer of 2002, secret plans were drawn up about a possible invasion. In late September, the Bush administration asked Congress for authority to go to war with Iraq. This was couched as a bargaining tool and would only be done as a last resort if Iraq failed to allow inspectors full access to the country to ferret out weapons of mass destruction. Congress voted in support of the request on October 16. In a nationally televised speech that night, Bush made it clear that he hoped that war would be avoided. In an article by New Yorker writer and Berkeley journalism professor Mark Danner, British documents eventually surfaced proving that, with the final blessing of the U.S. Congress, war was a virtual certainty.

Imagine you are a leader and you know you are going to attack another country. To be effective, you have to keep your plans completely secret. You can’t let anything slip about troop movements, rescaling vast parts of the country’s economy, or letting your enemies know what your plans might be. You must be wary about what you say. Not only must you be deceptive, you have to pay attention to every facet of government to coordinate the clandestine war effort. To accomplish all of this, an effective leader must act—and not sit around contemplating his or her feelings.

Drops in I-words are a powerful tell among people who are about to carry out a threat. We have found similar patterns in Truman’s language prior to dropping the atomic bombs on Japan in World War II and in Hitler’s speeches prior to his invasion of Poland in 1939.

The idea that the language of leaders can predict the outbreak of wars has been suggested by others as well. The Belgian psychologist Robert Hogenraad has studied how leaders mention themes of power and affiliation in their speeches. When references to affiliation and friendship are commonplace and comments about power, aggression, and mastery are low, the outlook for the country is usually good. However, if themes of power and aggression start to rise with a corresponding drop in words associated with nurturance and relationships, watch out. High power/low affiliation themes among leaders is a reliable predictor of wars. Conflicts in Northern Ireland, the former Yugoslavia, Georgia and Russia, and various hotspots in the Middle East all were presaged by language shifts by the countries’ leaders.

One final observation. It’s interesting that Bush’s I-words never changed substantially once the war started. They temporarily went up a bit coinciding with his “Mission Accomplished” speech in May 2003, when he felt that the war was over. Subsequent drops in I-word use in the summers of 2003 and 2004 reflect his increasing focus on the war and, in 2004, his defensiveness with the press for its questioning his decisions about it.

THE POWER OF WORDS TO RETHINK HISTORY

I’ve tried to give a taste of the exciting possibilities that word analysis can bring to the study of politics and history. Wherever there is a word trail—no matter what language—computer text analysis methods can help interpret the psychology of the authors. Some of the studies in this area have practical applications. Other work is simply fun to do.

For example, my students, colleagues, and I have worked with several federal agencies to better understand the psychology of leaders of groups such as al-Qaeda to try to understand the relationships between their public messages and their sometimes-brutal actions. Can we understand their appeal by studying their language or the language of their followers? We have used these same methods to better understand extremist groups in the United States, ranging from far-right-wing neo-Nazis to far-left-wing Weathermen. In general, we are finding the violent groups have a very different linguistic fingerprint than nonviolent ones. Further, as they evolve from being nonviolent to increasingly violent, their language shifts accordingly.

We have also turned our language tools to the study of powerful, often despotic leaders of the past and present. For example, how have leaders such as Mao, Hitler, Castro, and others changed in their language use as they themselves changed from revolutionaries, to dictators, to sometimes-respected leaders in their countries? How has their language predicted changes in their countries and how have events changed their language?

Most important, language analyses can shed light on historical events in new ways. We’ve seen some possibilities with the Federalist Papers, relationships among poets and scholars, and even the Beatles. The historical questions that can be answered are limited only by the availability of language samples and the researchers’ imaginations. For example, did the Australian explorer Henry Hellyer really commit suicide or might he have been murdered? (Probably suicide based on his language in his diaries.) Did St. Paul really write all the letters attributed to him in the Bible? (Nope—not a chance.) Has Lady Gaga had an affair with Tom Cruise? (No idea. Hope not.)

Now it’s your turn.

USING PEOPLE’S WORDS TO PREDICT THEIR BEHAVIORS IN THE FUTURE

Can word analyses tell us if someone will eventually be a good president, a good spouse, a good employee or student? In fact, we do these calculations in our heads all the time. If a student writes to me and wants to work in my lab, I read her e-mail, her résumé, and her plans. Her words—which reflect her accomplishments, hopes for the future, and personality—will be the basis of my decision. People who rely on online dating sites may ultimately decide who their spouse will be based on his or her word use. And yes, we weigh political candidates’ faces and body language, but we also evaluate their platforms and plans, which are expressed in language.

Although we listen to and think about people’s words before voting for, hiring, or marrying them, it is impressive how frequently we err in our judgments. Would a language analysis program do a better job? Or would it help us in making better decisions? The jury is still out, but some interesting examples can be found among students planning to go to college and prisoners planning to find a normal life.

USING WORDS IN COLLEGE ADMISSIONS ESSAYS TO PREDICT COLLEGE GRADES

My linguist friend David Beaver and I were sitting in a bar talking about pronouns. (How many bar stories have you heard start off that way?) Wouldn’t it be great if there was some simple relationship between word use and how people later behave in life? We started to challenge each other about possible language samples we could get that could be linked to important real-world behaviors. And then I remembered Gary Lavergne.

Several years earlier, I had met Gary, the chief researcher in the University of Texas at Austin’s admissions office. Gary was not your usual statistician. He has published a series of nonfiction thrillers on mass murderers and, most recently, a book on the history of school desegregation in Texas. He was also interested in what factors predicted who would succeed in college. The University of Texas always has one of the largest student bodies of any campus in the United States. Although the school enrolls over seven thousand new first-year college students each year, the admission standards are surprisingly competitive. Part of the application process involves students writing two general essays.

Could the function words students use in their admissions essays predict their college grades? This was an appealing question for both David and me and, as it turned out, for Gary as well. To be clear, this was not a strategy to invent a new way to evaluate college essays to determine who should be admitted. Rather, we first wanted to learn if word use was related to academic performance and, if it was, whether we could influence the students to become better writers and thinkers in college.

We eventually analyzed over fifty thousand essays from twenty-five thousand students who had enrolled over a four-year period. The results were straightforward. Word use was indeed related to students’ grades over all four years of college. The word categories most strongly related to making good grades were:

• High rates of articles and concrete nouns

• High rates of big words

• Low rates of auxiliary and other verbs (especially present tense)

• Low rates of personal and impersonal pronouns

This constellation of words should look familiar to you. You might recall from earlier chapters that people differ in the degree to which they are categorical versus dynamic thinkers. A categorical thinker is someone who tends to focus on objects, things, and categories. The opposite end of this dimension are people who are more dynamic in their thinking. When thinking dynamically, people are describing action and changes. Often, dynamic thinkers devote much of their thinking to other people (which explains their high use of pronouns).

Does this mean that categorical thinkers are simply smarter than dynamic thinkers? Not at all. However, the American educational system is designed to test people concerning the ways they categorize objects and events.

Look at these two examples of college admissions essays that display categorical versus dynamic thinking. (The actual content of these essays has been changed considerably while keeping the rate of articles, nouns, large words, verbs, and pronouns intact.)

The categorical thinker

The concept of choice has played a prominent role in Western philosophy. One’s personality is polished to a more defined state by both conscious and unconscious considerations. The ultimate aim of liberty cannot be reached without a thorough control over the choices one makes. The divorce of my parents made me lead a double life. My partial withdrawal from reality had severe negative effects, including the inability to understand other viewpoints …

Notice how the writer’s sentences methodically define and categorize thoughts and experiences. The writing is structured and largely impersonal but, at the same time, ponderous. Compare the categorical thinker with a more dynamic one.

The dynamic thinker

I looked over at my brother, who was much older and wiser, only to see him crying. Before I knew it, I was crying too. I didn’t really know why, but if my brother thought it was bad, it was bad. Everyone moves, but it was the magnitude of my journey, a seven-hundred-mile trip from a small farming village to one of the biggest cities in America. It was going to be challenging but also an opportunity to grow. It involved giving up everything that is important to young children; family, friends, school.

The dynamic writer is far more personal and works to tell a story. The language is more informal and simple, using shorter words. Every sentence has multiple verbs, which has the effect of making the story more alive.

Although both of these students came to college with virtually identical high school records and received liberal arts degrees, the categorical thinker had a much higher grade-point average every year in college. It wasn’t because the categorical thinker was a better writer. Rather, a categorical thinking style is more congruent with what we reward in college. Most exams, for example, ask students to break down complex problems into their component parts. At the same time, very few courses ask students to discuss ongoing events or to tell their own stories.

Most universities will never use word counting programs to decide who to admit to college. Once students discovered such a system was operative, their admissions essays would be a jumble of big words and articles, and practically verb-free. Instead, findings such as these point to ways we might think about training our students in high school and earlier. To the degree that categorical thinking is encouraged and rewarded in our educational systems, students should be explicitly trained in doing it.

Another argument is that we should explore whether dynamic thinking should be encouraged at the college level. Telling stories and tracking changes in people’s lives are skills that can serve people well. It also raises the question about how successful people are in the years after college. Is it possible that dynamic thinkers are better adjusted or happier? And finally, how flexible is thinking style? It is entirely possible that all of us occasionally need to think categorically and, at other times, dynamically.

USING WORDS TO PREDICT A BETTER LIFE AFTER PRISON

Drug and alcohol abuse takes a massive toll on society. One way that many states have attempted to curb and treat abuse is by establishing therapeutic communities—which are essentially treatment prisons where people are given the opportunity to undergo intensive drug and alcohol rehabilitation over several months after they have been convicted of a drug-related crime. If the participants successfully complete the program and stay drug- or alcohol-free for a specified time after they are released, their records are usually expunged. Most therapeutic communities require intensive group therapy along with writing exercises.

One of my former graduate students, Anne Vano, conducted an ambitious project to learn if the ways women wrote within a treatment facility might predict their lives once they were released from prison. Working with a single therapeutic community, Anne collected and transcribed writing samples from about 120 women. The writing samples she focused on were essays that the women wrote within about a week of their being released. The essays were expected to be personal and heartfelt. In the months afterward, Anne worked with the warden’s office to collect follow-up information, such as the women’s abilities to maintain jobs and whether or not they violated their parole or were re-arrested.

The stories the women wrote were powerful by any measure. They often described instances of being the victims of physical and sexual abuse and, at the same time, detailed their own deplorable behaviors toward others, such as their children. They often expressed great anxiety about their leaving the prison to return to an uncertain home life.

After leaving the prison, 15 percent of the 120 women were arrested and another 10 percent jumped parole four months after the program was completed. About 65 percent were holding down a steady job.

Interestingly, the way the women wrote in their final essay modestly predicted whether they were functioning effectively four months later. The two language dimensions that were most closely associated with therapeutic success were:

• a high social-emotional style, which includes use of personal pronouns and emotion words

• a high rate of positive emotion words

The tasks for the women on leaving the therapeutic community were to integrate into new jobs and into a functioning social network. Categorical and dynamic thinking were simply irrelevant dimensions for these women. To survive in their worlds outside prison they needed to be aware of others and themselves. It appears that the social-emotional and optimistic styles they exhibited in their writings were skills that could serve them well on the outside.

IT’S HARD TO imagine two studies more different than the college admissions and therapeutic community projects. Categorical thinking predicts better college grades for one group; social-emotional language predicts lower re-arrest rates in another. Different aspects of language are linked to different parts of our lives.

What I love about these two studies—and, in fact, all of the projects in this book—is that stealth words rearrange themselves in different configurations to predict a broad array of behaviors. For example, using language associated with high social-emotional style can help keep you out of prison and contribute to your being elected president and maybe provide some of the skills needed to write successful top-selling love songs.

Depending on the context, using I-words at high rates may signal insecurity, honesty, and depression proneness but also that you aren’t planning on declaring war any time in the near future. Using I-words at low rates, on the other hand, may get you into college and boost your grade-point average but may hurt your chances of making close friends.

It’s important to return to a theme that has bubbled up several times. The words related to social and psychological states are reflections of those states—not causes. They are telling us what is going on inside people’s heads. The people who use high rates of personal pronouns and emotion words just prior to their release from prison are approaching their writing topic in a social-emotional way. It’s unknown if the treatment program they were immersed in actually pushed them to think social-emotionally. It is also impossible to know if the words in their writing samples directly affected their behaviors once they were released. And it’s even more unlikely that if they had forced themselves to use these words in their essays (thinking it might be good for them) it would have influenced their lives outside the prison gates at all.

We are standing on the threshold of a new world. Think of the many applications that the computer analysis of function words has opened up. By analyzing inaugural speeches or ancestral diaries, we are able to know the influential writers or speakers of our past. We can also start to answer some of the burning psychological questions we have in our everyday lives. We can gain insight into how our online dating prospects view us, distinguish which rap artists are honest about being true gangsters, diagnose if our therapists are just as depressed as we are, or expose which of our colleagues secretly think they are highest in status.

Function words can help us know our worlds just a little better. From author identification that can help in catching criminals or in identifying historical authors, to understanding the thinking of presidents or tyrants, to predicting how people might behave in the future, function words are clues about the human psyche. Most promising, however, is that by looking at our own function words, we can begin to understand ourselves better.