CHAPTER 2

Ignoring the Content, Celebrating the Style

ALL WORDS ARE not equal. In any given sentence, some words provide basic content and meaning whereas others serve quieter support functions. Ironically, the quiet words can say more about a person than the more meaningful ones. A central theme of this book is that the content of speech can be distinguished from the style of speech. Further, words that reflect language style can reveal aspects of people’s personality, social connections, and psychological states.

This chapter lays out the overall logic of word analysis. It serves as the foundation for the rest of the book. If you simply want to see how different types of words reflect personality, deception, and psychological state, feel free to skip this chapter. You may well regret it. But then you will never know.

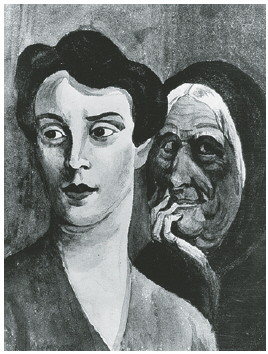

IT’S HELPFUL TO start with a simple exercise to give you a feeling about the ways different words work. Look closely at the picture on the next page. Who are the people? What is happening? What are their thoughts, feelings, and concerns?

How would you write or talk about this drawing? Stop for a second and describe the picture to yourself. You might even jot down your description on a piece of paper so that you can refer back to your writing throughout the chapter.

In fact, thousands of people have written about this picture as part of various psychology experiments. The kinds of stories that people tell vary widely. Some view the people as two women, others as one or two men. Some cast the two as part of a story dealing with good versus evil, wisdom versus youth, or just a family relationship between people of different generations.

Despite the differences in stories and themes, the ways people write their stories are even more striking. As an example, read the first sentences that three college students wrote in describing the picture:

PERSON 1: In the aforementioned picture an elderly woman is about to speak to a middle aged woman who looks condescending and calculating.

PERSON 2: I see an old woman looking back on her years remembering how it was to be beautiful and young.

PERSON 3: The old woman is a witch or something. She looks kinda like she is coaxing the young one to do something.

Now look more closely at each person’s writing. Can you get a sense of who each of these three people is? Who would you like to get coffee with? Which one do you trust the most? What factors influenced your answers? Although all three students saw the same drawing, they interpreted it differently. More important, however, is how they used words to describe their impressions. Even in these brief sentences, you get a sense of who these students are. The first person appears stiff and distant, relying on large words in a self-conscious way. The second has a more personal and warmer touch. The third person sounds more casual than the other two and seems not to be taking the assignment as seriously.

All three people have stamped part of their personality into their writing style. Through their largely unconscious use of words, we can begin to get a sense of who they are, how they think about others and about themselves. We can do a reasonably good job in predicting that person 1 is a male and the other two are females. He probably has a higher grade average than the other two, although his social life is likely suffering. Person 2 is the one most likely to be depressed. Person 3 is probably not doing well in school—and may well be spending too much time with friends and drinking too much.

These are more than educated guesses. They are based on evidence that the words people use in their daily lives can tell us a great deal about their personality, age, sex, social class, stress levels, biological activity, and social relationships. Words leave behind clues of a person. By analyzing these clues, we get a glimpse of each author’s personal world.

What could someone tell about you based on the words you used to describe the picture? How do we know that person 1 is a socially isolated male and person 2 is a depressive female? The secret is in distinguishing between what people are saying versus how they are saying it. Looking back at the three statements, the content of the writing is certainly different, but more striking is the way they are expressing themselves. There is a meaningful difference, then, between language content and language style.

IT AIN’T WHAT YOU SAY, IT’S THE WAY YOU SAY IT

What accounts for style? Gordon Allport, a founder of modern-day personality psychology, asked this question in trying to define the essential differences among people. He noted that people revealed themselves in almost everything they did. Some walk quickly and don’t move their arms; others seem to skip by bouncing on the balls of their feet; yet others amble, careen, or trudge along. Walking styles, he argued, are one way that people differ. But they also differ in the ways they dress, eat, and peel an orange. Style may not tell us much about where a person is walking, how hungry they are, or their preferences for fruit, but it is a meaningful window into people’s personality, attitudes, and social worlds.

Language style is no exception. How people speak or write reveals meaningful clues to personality. The challenge is in determining what accounts for style. Interestingly, linguists, high school English teachers, and Mother Nature have provided us with some hints about words that reflect style versus content.

Content words are words that have a culturally shared meaning in labeling an object or action. For our purposes, content words include:

Nouns e.g., table, uncle, justice, Fido

Regular and action verbs e.g., to love, to walk, to hide

Most modifiers e.g., adjectives (blue, fast, mouthwatering) and adverbs (sadly, hungrily)

Content words are absolutely necessary to convey an idea to someone else. Consider the three people who wrote briefly in response to the picture.

PERSON 1: In the aforementioned picture an elderly woman is about to speak to a middle aged woman who looks condescending and calculating.

PERSON 2: I see an old woman looking back on her years remembering how it was to be beautiful and young.

PERSON 3: The old woman is a witch or something. She looks kinda like she is coaxing the young one to do something.

Imagine you are talking with someone whose English is very poor. That person is trying to describe the picture. All you can understand are the content words that are highlighted. The fact is, you can get a good sense of what the speaker is trying to say by just hearing the content-related words. That’s good. Content words should convey content. Admittedly, this wouldn’t be a very satisfying interaction but you would be fairly certain what was going on in the speaker’s mind.

Style (or function) words are words that connect, shape, and organize content words. Although this definition is a bit slippery, most style words fall into a general class of words variously referred to as function words, stealth words, or even junk words. A good way to think about style words is that, by themselves, they really don’t have any meaning to anyone. For example, a content word like table can trigger an image in everyone’s mind—the same with words like walking, blue, and bug. Now try to imagine that or because or really or the or even my. We might use words like this in most sentences but they are fairly useless on their own.

Most function words include:

CATEGORY |

EXAMPLES |

Pronouns |

I, she, it |

Articles |

a, an, the |

Prepositions |

up, with, in, for |

Auxiliary verbs |

is, don’t, have |

Negations |

no, not, never |

Conjunctions |

but, and, because |

Quantifiers |

few, some, most |

Common adverbs |

very, really |

To appreciate the significance of these often-misunderstood words, let’s return to our three people describing the picture.

PERSON 1: In the aforementioned picture an elderly woman is about to speak to a middle aged woman who looks condescending and calculating.

PERSON 2: I see an old woman looking back on her years remembering how it was to be beautiful and young.

PERSON 3: The old woman is a witch or something. She looks kinda like she is coaxing the young one to do something.

Now imagine that someone was only able to speak to you using the highlighted style words while trying to describe the picture. You would have absolutely no idea what the person was talking about.

Why make such a big deal about style words? Because pronouns, prepositions, and other function words are the keys to the soul. OK, maybe that’s a bit of an overstatement, but bear with me. Stealth words are:

• used at very high rates

• short and hard to detect

• processed in the brain differently than content words

• very, very social

Each of these features helps to explain why function words are psychologically important and, at the same time, why so few people have examined them closely. Stealth words, then, really are quite stylish. It’s about time that these forgettable, throwaway little words get their due.

FUNCTION WORDS IN EVERYDAY LANGUAGE: THEY’RE EVERYWHERE

In 1863, four months after the devastating Battle of Gettysburg, Abraham Lincoln delivered one of the most significant speeches in American history. Overlooking the battlefield where 7,500 soldiers died, Lincoln’s brief speech helped to reframe the Civil War. Read his speech quickly so that you can form an impression of what’s being said.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled, here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here.

It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Now, close your eyes and reflect on the content of the speech. Which words occurred most frequently? In your mind, try to recall which words Lincoln used the most in penning such a powerful speech. I’m serious. Shut your eyes and make a list in your mind of the most frequently used words in this speech.

OK, you can open your eyes. Most unsuspecting people who are asked to do this will think the most common words are nation, war, men, and possibly dead. You probably won’t be surprised to learn that function words are far more frequent than any content words. In this particular speech, the most commonly used word was that, which was used twelve times and accounted for 4.5 percent of all the words in the speech. Other frequently used words: the (4.1 percent), we (3.7 percent), here (3.5 percent), to (3.0 percent), a (2.6 percent), and (2.2 percent), can, for, have, it, not, of, this (1.9 percent each). In fact, these fourteen little words account for almost 37 percent of all the words Lincoln used in this beautifully crafted speech. Only one content word is in the top fifteen, nation, which was used only 1.9 percent of the time. It is remarkable that such a great speech can be largely composed of small, insignificant words.

A very small number of stealth words account for most of the words we hear, read, and say. Over the last twenty years, my colleagues and I have amassed a very large collection of text files that includes thousands upon thousands of natural conversations, books, Internet blogs, music lyrics, Wikipedia entries, etc., representing billions of words. Although there are some variations in word use depending on what people are writing or saying, it is striking to see how common function words are in all types of text.

Spend a minute inspecting the word table on the next page. This is a list of the twenty most commonly used words in English based on our large language bank. Across both written and spoken text, for example, the word I accounts for 3.6 percent of all words that are used. If you consider these twenty words together, they represent almost 30 percent of all words that people use, read, and hear.

Notice that all of the words in the table are quite short and are made up exclusively of pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles, and auxiliary verbs. If we extended the list to all of the common stealth or function words in English, the list would include around 450 words. Indeed, these 450 words account for over half (55 percent) of all the words we use.

THE MOST FREQUENTLY USED WORDS ACROSS BOTH SPOKEN AND WRITTEN TEXTS |

||

RANK |

WORD |

PERCENTAGE |

1 |

I |

3.64 |

2 |

the |

3.48 |

3 |

and |

2.92 |

4 |

to |

2.91 |

5 |

a |

1.94 |

6 |

of |

1.83 |

7 |

that |

1.48 |

8 |

in |

1.29 |

9 |

it |

1.19 |

10 |

my |

1.08 |

11 |

is |

1.06 |

12 |

you |

1.05 |

13 |

was |

1.01 |

14 |

for |

0.80 |

15 |

have |

0.70 |

16 |

with |

0.67 |

17 |

he |

0.66 |

18 |

me |

0.64 |

19 |

on |

0.63 |

20 |

but |

0.62 |

To put this in perspective, the average English speaker has an impressive vocabulary of perhaps one hundred thousand words. This means that only a trivial percentage of the words we know are associated with linguistic style—about 0.04 percent of all words. The other 99.96 percent of our vocabulary is made up of content words. This split is comparable in other languages—German, Spanish, Turkish, Arabic, Korean, and others we have studied. In all languages, a small number of function words are used at dizzying rates compared to a large number of content words that are used at very low rates.

Briefly consider the implications of these numbers. If you want to learn a new language such as German or Finnish, you can pick up almost half the language in an afternoon. Most anyone can master the top one hundred stealth words with minimal training. By early evening, you could sit down with any German newspaper or Finnish philosophy text and identify half of the words that were used. The only downside is that you would have absolutely no idea what you were reading.

FUNCTION WORDS: THEY’RE SHORT AND ALMOST INVISIBLE

Look back at the top twenty function words. You will notice that seventeen of the twenty words are three letters or fewer in length. The most common words in every language tend to be short and are usually a single, easy-to-pronounce syllable.

Not only are stealth words short, they are hard to perceive. One reason we have trouble spotting the high usage of function words in the Lincoln speech is that our brains naturally slide over them. We automatically focus on content-related words instead. The invisibility is also evident in the ways we remember words. Think, for example, of the last conversation you had with someone. Can you recall any specific words that the other person spoke? In all likelihood, you remember only the content words.

Perhaps the strongest test of invisibility is in actively trying to listen to people’s use of style versus content words. Sit by a television or radio or simply begin listening to people speaking around you. Consciously try to attend to style-related words. You will note that they are spoken extremely quickly—lingering, on average, for less than two-tenths of a second. In fact, this speed is often used in psychology experiments to present words or pictures that are just barely perceptible. Assuming you are able to pay attention to these words for a few minutes, you will find that you lose track of what the content of the conversation is. It is almost impossible to attend to function words on their own.

THE AMAZING CASE OF JOHN KERRY AND HIS INVISIBLE PRONOUNS

In the 2004 presidential campaign, Democrat John Kerry was running for president against the incumbent George W. Bush. In the months running up to the election, Bush’s popularity ratings were suffering and Kerry posed a serious threat. A recurring problem with Kerry, however, was that he came across as aloof and somewhat arrogant. When he spoke, his body language was rigid and standoffish. His speeches and interviews tended to sound wooden and inauthentic.

According to a New York Times article, in an attempt to appear more warm, Kerry’s advisers were working with him to use we-words (e.g., we, us, our) more and I-words less. On reading the article, it was clear that Kerry was in trouble.

As will be detailed later, use of I-words is associated with being honest and personal, and when politicians use them, we-words sound cold, rigid, and emotionally distant. At the time, Kerry was already using we-words at twice the rate of Bush and I-words at half Bush’s rate. Kerry’s advisers, who were some of the smartest people in the country, failed to understand how invisible stealth words worked.

This should be an important lesson. Function words are almost impossible to hear and your stereotypes about how they work may well be wrong.

Another surprising aspect of stealth words is that they are very hard to master after about age twelve. Learning another language as an adult is usually quite difficult. However, most people can quickly learn the words for objects, numbers, and colors. They can also memorize the words for, in, above, with, and related words. But mastering the use of most common function words in an ongoing conversation is far more difficult. In fact, you can usually tell if someone is not a native English speaker by looking at their writing. Their errors will likely be in their use of style words rather than any nouns or regular verbs.

STYLE WORDS AND THE BRAIN

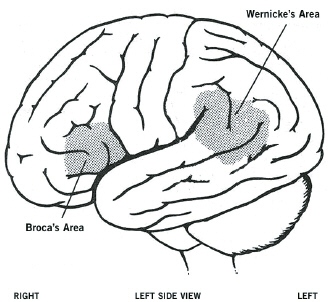

The distinction between style and content words can also be seen in people who suffer from brain damage. Occasionally, a person will have a stroke or other brain injury that affects a highly specific location on the left side of the brain. If it is in one area, the person can lose the ability to use content words but still retain the ability to use function words. Strokes in other areas can produce the opposite results.

The two brain areas of interest—Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area—are usually located on the outer surface of the left side of the brain, called the cerebral cortex.

Broca’s area, named after the nineteenth-century French surgeon Paul Broca, is located in the frontal lobe. In the 1860s, Broca published a series of articles reporting that damage to Broca’s area was often associated with patients speaking in a painfully slow and disconnected way. More striking, however, is that they often were unable to use function words effectively. As an example, if a Broca’s patient were asked to describe the picture at the beginning of the chapter, he or she might say, “Girl … ummm … woman … ahh … picture, uhhh … old. OK. Old woman.” Often, Broca patients are socially awkward and frustrated by their inability to communicate with others.

The discovery of Broca’s area became more significant several years later when Carl Wernicke published his observations about another brain area in the temporal lobe of the brain now called Wernicke’s area. Damage to this area resulted in a completely different set of symptoms. Specifically, Wernicke damage often results in people’s inability to use nouns and regular verbs while, at the same time, they freely use function words. A Wernicke patient who is asked to describe the same picture might say something like, “Well, right here is one of them and I think she’s next to that one. So if I see over there you’ll see her too. Let’s see. I’m thinking of her now. She’s over there.”

To say that Broca’s area controls style words and Wernicke’s controls content words is a gross oversimplification. Nevertheless, it points to the fact that the distinction between content and style words is occurring at a fairly basic level in the brain.

Particularly noteworthy is that Broca’s area—the region linked to function words—is in the frontal lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe controls a number of skills, many of them social. For example, dozens of studies have demonstrated how frontal areas are linked to abilities to express and conceal emotions. Other frontal areas are associated with the ability to read other people’s facial expressions. A number of promising studies now suggest that many of our abilities to control our emotions and to establish social relations with others are related to frontal lobe activity.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of frontal lobe damage and changes in social behavior and personality was the case of Phineas Gage. Gage was an explosives expert for a railroad in the mid-1800s. By all accounts, he was a careful, conscientious, and serious individual. One summer day, he was tamping down some blasting powder in preparation for an explosion to clear some rocks. He accidentally created a spark with his long tamping rod that ignited the powder, causing the rod to shoot upward, where it neatly tore a hole through his skull and destroyed much of his frontal lobe. To everyone’s amazement, Gage wasn’t killed and he returned to good health within a few weeks. That is, except for the hole in the front of his head. Over the next months, Phineas Gage’s personality changed dramatically. He went from reserved to loud, from conscientious to impulsive, from respectful to obscene, and from sober to, well, not sober. He was a completely different person and never returned to his old personality.

In the early 1900s, Ivan Pavlov noted the same thing in his research with dogs. Pavlov, who won one of the first Nobel Prizes, is best remembered for his experiments where a dog could be trained to salivate when a bell rang. In a failed attempt to find the location of classical conditioning in the brain, Pavlov surgically disrupted different parts of dogs’ brains. He reported that only damage to the frontal lobe affected the animal’s personality. Although the dogs with frontal lobe injury still remembered things from before the surgery, they were simply different dogs.

If the frontal lobe is closely linked to personality and social behaviors, it is not surprising that any language areas in the frontal lobe—such as Broca’s area—would also be related to personality and social behaviors.

FUNCTION WORDS ARE VERY VERY SOCIAL

Brain research points to the inescapable conclusion that function words are related to our social worlds. In fact, stealth words by their very nature are social.

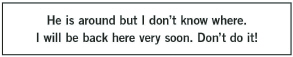

Imagine you are walking down the street on a windy afternoon and a piece of paper lands on the ground in front of you. There is a handwritten note on the paper that says:

The note is grammatically correct and is understandable in a certain sense. Is something important about to happen? Certainly there is an urgency. But, really, we have no idea what this person is talking about. Every word in the note is a function word. Who and where is “he”? When is “will be” and “soon”? Who is “I”? Where is “here”? What shouldn’t the person do? Now that you think about it, this note makes absolutely no sense.

In a normal conversation, we automatically know what all the function words refer to based on who we are speaking to, where we are, and what we have already been talking about. Whoever wrote the note had a shared understanding with its intended recipient about the who, where, and when. Maybe the note was typed by some guy named Bob to be read by Julia. A few minutes earlier, they might have had the following discussion:

BOB (ON CELL PHONE TALKING TO JULIA): Julia, you caught me at a crazy time. I’ve got to buy a stapler but I’ll leave a note on the door if I’m not here when you arrive.

JULIA: Great. I need to have the accountant sign my expense form. Do you know where he is?

BOB: I’ll see if he’s in …

JULIA: Did I tell you that I’m thinking of smoking again? I always feel more alert and happy when I smoke. I know it annoys you.

BOB: Are you nuts? Let’s talk about this. Gotta go. See you later.

All of a sudden, we know that “He is around” = the accountant is somewhere in the building, “I” = Bob, “will be back very soon” = Bob will be back at work within maybe thirty minutes of when the note was written, “Don’t do it” = Julia really shouldn’t start smoking again.

What’s interesting is that this note has real meaning only for Bob and Julia on a specific day in a specific location. If Julia finds the note in a week it will no longer make sense. Any stranger who happens on the note will not have the keys to unlock the meanings of all of these function words.

Function words require social skills to use properly. The speaker assumes that the listener knows who everyone is. The listener must be paying attention and know the speaker to follow the conversation. So the mere ability to understand a simple conversation chock-full of function words demands social knowledge.

The same is true for articles, prepositions, and all other stealth words. Consider these slightly different sentences:

“I can’t believe that he gave her the ring.”

“I can’t believe that he gave her a ring.”

The difference between “the” ring and “a” ring is subtle but significant. If the word the is present, it means that the speaker is referring to a specific ring that the listener has some knowledge of. The sentence with “a” ring, in contrast, suggests something very different about the evolving relationship between “him” and “her.” More important, “a” ring tells us that the speaker and listener do not have a shared knowledge of the particular ring that was given.

All function words work similarly in that they are tied to the personal relationship between the speaker and listener. Even the author of a book and the book’s reader must enter into a shared social world. If I now make reference to the earlier paragraph about Julia’s smoking, you instantly know what I, now, to, the, earlier, and about refer to. Had that same phrase been written three pages ago, no one would have been able to figure it out. All function words, such as before, over, and to, require a basic awareness of the speaker’s location in time and space. The ability to use them, then, is a marker of basic social skills. On the other hand, talking about nouns and verbs demands the ability to understand culturally shared categories and definitions.

What’s so amazing is that our brains are able to decide which function words to use almost instantaneously. Assuming you are a native English speaker, no one has ever sat down with you and explained the difference between using a and the. If we are talking with someone we have never met and casually mention a particular window in the room, two minutes later both of us will know which window when it is referred to as “the window.” Similarly, when we later refer to it as being clean, we will remember that “it” = the window.

Function words also reflect and color subtle ways we think about objects and events in our lives. With prepositions and other function words, as with articles and pronouns, we are able to make linguistic shifts as quickly as we can speak. It’s hard to imagine stopping a conversation in midsentence to decide whether you should say “I went to my friend’s house” versus “I went over to my friend’s house” versus “I went by my friend’s house.” The differences among to, over to, and by are almost imperceptible to the listener but they all have a slightly different meaning about the trip or the friend or the friend’s house.

As a final note, we are not capable of easily controlling how and when we use function words. They are hard for us to perceive in others and to control in ourselves. They are processed in our brains extremely quickly and efficiently. All the time, our brain is remembering recent references to a person or object so that we can use the right pronouns and articles in the next sentence.

BEYOND ENGLISH: FUNCTION WORDS AS CULTURAL CLUES

Every language must be able to distinguish between “a table” and “the table,” between “she” and “he,” and between “going to a store” and “going by a store.” In some languages these distinctions are signaled by separate function words and in others, they are added to a surrounding noun or verb. The ways that function words are used differ by culture and often tell us something about the culture itself.

In our research on function words, my students, colleagues, and I have developed the LIWC computer program for use with a number of languages, including Spanish, German, Arabic, Italian, French, Russian, Dutch, Chinese, and others. So far, virtually all the language links to social and psychological phenomena we have found in English have generalized to other languages. In developing cross-language text analysis programs, we come across unique issues every time we begin exploring a new language.

Pronoun Dropping

In some languages, separate words for pronouns are rarely used. In Spanish, for example, estoy triste literally means “am sad.” The word “I” is not needed since the personal pronoun is implicit in the verb conjugation. Of course, a speaker could say “Yo estoy triste,” which would be the equivalent of “I am sad,” with a strong emphasis on the word I. As discussed in the emotion chapter, when English speakers are depressed, they tend to use the word I more in everyday language—apparently because they are paying more attention to themselves. Spanish speakers, when they are depressed, greatly increase in their use of the first-person singular pronoun, yo.

Why do some cultures drop personal pronouns and others don’t? One argument is that languages from more tightly knit collectivist cultures tend to drop pronouns, whereas the more individualist societies retain them.

Status Markers in Language

Most languages are constructed to identify who in a conversation has greater status or respect. In Old English, our linguistic ancestors distinguished between you and thou. By the late eighteenth century, the formal and informal distinction was disappearing. Most European languages still use formal and informal versions of the pronoun you, although the distinction is becoming less common. Other languages, such as Japanese, signal relative status in the conjugation of verbs and other words. Indeed, it is almost impossible to say “I spoke with you about the car” without signaling the relative status of the speaker and addressee.

Direct Versus Indirect Knowledge

Some languages, such as Turkish, require you to provide evidence for any statement you make. If I said to you “It was very hot in Austin yesterday” in English, you would likely shrug your shoulders and assume that I’m telling you the truth. In Turkish, however, you would use different forms of the verb “was” to denote whether I personally experienced the hot weather or am simply relaying this information from some other source.

Social Knowledge Lost in Translation

In a striking series of studies, Stanford’s Lera Boroditsky has demonstrated how the language you are speaking at the time dictates how you remember pictures or events. A bilingual Japanese-English speaker would likely remember the relative status of three other people if introduced to them in Japanese rather than in English. A bilingual Turkish-English speaker will remember my talking about Austin’s weather differently if we spoke in Turkish compared to English.

Indeed, when anything is translated from one language into another, parts simply disappear or are created. If I have to translate “thank you very much” into Spanish, I will have to make an educated guess whether to make it a formal or an informal you. And when the same phrase is translated back into English, the formality information is stripped away.

Interestingly, nouns and regular verbs generally translate across languages fairly smoothly. It is the function words that can cause the biggest problems.

LANGUAGE STYLE AND PSYCHOLOGY: MAKING THE LEAP TO THE NEXT LEVEL

Function words are everywhere. We use and are exposed to them all the time. They are virtually impossible to hear and to manipulate. And many of these stealth words say something about the speaker, the listener, and their relationship. But this book really isn’t about function words per se. If you are talking with a friend and mention “a chair” versus “the chair” versus “that chair,” it really says very little about you. However, what if we count your use of articles over the course of a day or week? What if we find that there are some people out there who use a and the at very high rates and another group that tends to not use articles at all?

In fact, there are people who use articles at very high rates and others who rarely use them. Across hundreds of thousands of language samples from books to blogs to everyday informal conversation, men consistently use articles at higher rates than women. And, even taking people’s sex into account, high article users tend to be more organized and emotionally stable. Indeed, men and women who habitually use a and the at higher rates tend to be more conscientious, more politically conservative, and older.

And now things start to get interesting. Using articles in daily speech doesn’t make a person a well-adjusted, older conservative politician like John McCain (who, in fact, used articles at high rates compared to his opponents in the 2008 presidential election campaign). Rather, the use of articles can begin to tell us about the ways people think, feel, and connect with others in their worlds. And the same is true for pronouns, prepositions, and virtually all function words.

This is the heart of my story. By listening to, counting, and analyzing stealth words, we can learn about people in ways that even they may not appreciate or comprehend. At the same time, the ways people use stealth words can subtly affect how we perceive them and their messages. Before starting our journey on stealth words and the human condition, you might need a brief road map to jog your memory about what different function words mean. At the end of the book, a short word-spotting guide is available. As you study your own language or the words of others, you can refer back to the guide as needed to better understand what the words mean.