CHAPTER 3

The Words of Sex, Age, and Power

THERE IS NO better way to start a discussion of language and differences among people than with gender. Do men and women use words differently? As you may suspect, the answer is yes. Now that this has been established, take the following test.

In daily conversations, e-mails, informal talks, blogs, and even most formal writing, who uses the following parts of speech more, men or women?

For each of the questions, circle the correct answer:

1. First-person singular (e.g., I, me, my):

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

2. First-person plural (e.g., we, us, our)

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

3. Articles (a, an, the)

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

4. Positive emotion words (e.g., love, fun, good)

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

5. Cognitive words (e.g., think, reason, believe)

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

6. Social words (e.g., they, friend, parent)

a. women use more

b. men use more

c. no difference between women and men

This should be a very easy test for everyone. A day doesn’t go by where we don’t hear thousands of words from both men and women. In fact, we have all been deluged with words from people of both sexes our entire lives. Who could possibly miss these questions?

As it turns out, most people do. This includes the leading scholars in many top departments of psychology and linguistics around the world. Your high school English teachers would have done no better. How about you? The answers are: 1. a; 2. c; 3. b; 4. c; 5. a; 6. a. Women use first-person singular, cognitive, and social words more; men use articles more; and there are no meaningful differences between men and women for first-person plural or positive emotion words. If you are like most people, you probably got the social words question right and missed most of the others.

Before going farther, it might be helpful to review the test answer key:

1. Women use first-person singular pronouns, or I-words, more than men. People’s pronouns track their focus of attention. If someone is anxious, self-conscious, in pain, or depressed, they pay more attention to themselves. Research suggests that women, on average, are more self-aware and self-focused than are men. The differences in the use of I-words between women and men are not subtle. In natural conversations, blogs, and speeches, women use I-words at much higher rates.

2. Men and women use first-person plural words, or we-words, at the same rate. The use of we highlights one of the most enigmatic function words in our vocabulary. The natural assumption is that when speakers use we, they are referring to themselves and their close friends. There are even famous psychology studies where people see the word we flashed on a screen and it makes them feel all warm and fuzzy and more connected to others.

We, as it turns out, is really two very different words. Yes, there is the warm and fuzzy we—“my wife and I,” “my dog and me,” “my family.” You can feel the welcoming arms of the w and e embrace us. So, yes, there is that tight sense of group identity that goes with we some of the time.

Another we, however, is the cooler, distanced, and largely impersonal we. My graduate students know this we. It’s when I say, “You know, we really need to analyze that data.” My son rarely feels warm about his father when I say, “We need to take out the trash.” As it happens, I have no intention of actually analyzing that data. Nor am I proposing to my son that we take a family outing to the trash bin. In many situations, people use the word we when they mean you. It serves as a polite form to order others around.

A variation on the cool we-meaning-you is the royal we. “We are not amused,” Queen Victoria is supposed to have said, meaning that the queen herself was not amused. Soon after the birth of her first grandchild, England’s prime minister Margaret Thatcher announced to the press, “We have become a grandmother.” Royalty, office holders, and senior administrators occasionally slip in the royal we when they should really be using the word I.

Finally, there is the purely ambiguous we that is particularly loved by politicians. We need change in this country and we deserve it! Our taxes are too high and we need to do something about it! I sometimes sit around with my students trying to deconstruct political speeches in order to figure out who the “we” is. Sometimes, the politician means “you,” sometimes “I,” sometimes “you and I,” and sometimes “everyone on earth who agrees with me.”

The reason we is such a fun word is that half of the time it is used as a way to bring the speaker closer to others and the other half of the time to deflect responsibility away from the speaker. And indeed, there are sex differences. Women tend to use the warm we and men are more drawn to the distanced we. On average, however, men and women end up using we-words at about the same rates.

3. Men use articles (a, an, the) more than do women. Except for people who read the last chapter closely, hardly anyone would know the answer to this one. Articles? Who cares about articles? I do, for one. And I personally want you to care because they are very important words. Articles are used with nouns—especially concrete, highly specific nouns. A person who uses an article is talking about a particular object or thing. Guys talk about objects and things more than women do. They talk about the broken carburetor, the wife, and a steak on the grill for the dinner. We’ll return to this shameless generalization in a minute.

4. No differences in the use of positive emotion words. Although women use slightly more negative emotion words in everyday conversation than do men, the two sexes use positive emotion words at the same high rate.

5. Women use more cognitive words than men. Cognitive words are words that reflect different ways of thinking and include words that tap insight (understand, know, think), causal thinking (because, reason, rationale), and related dimensions. That women use more of these words is a slap in the face of Aristotle, who believed that women were less rational than men and incapable of philosophical thought. But there is a simple explanation. It all comes into focus with social words.

6. Women use social words at far higher rates than men. Social words refer to any words that are related to other human beings. Surely you got this one correct. Women do, indeed, think more and talk more about other people.

The various sex differences in word use actually make a coherent story. When women and men get together, what do they talk about? Women disproportionately talk about other people and men talk about, well, carburetors and other objects and things. Ultimately, which topics—other people versus carburetors—are more complex and require more cognitive work in explaining? Human relationships are not rocket science—they are far, far more complicated. We can get our top scientists together and send people to the moon. Two speakers—male or female—can troubleshoot a carburetor in under an hour. But even the most creative and diligent scientists, much less two interested speakers, are unable to understand, explain, or agree on why actress Jennifer Lopez is attracted to the men she is or how long she will remain married to her current husband.

PREPARATION FOR THE NEXT TEST: OTHER WORD CATEGORIES THAT DISTINGUISH BETWEEN MEN AND WOMEN

The sex-differences test you just took is only the beginning. Men and women differ in a variety of other language dimensions that will be discussed throughout the book. In case there is another gender-language exam, it is important to appreciate that men and women also differ in the following ways:

MEN USE MORE |

WOMEN USE MORE |

Big words |

Personal pronouns |

Nouns |

Verbs (including auxiliary verbs) |

Prepositions |

Negative emotion (especially anxiety) |

Numbers |

Negations (no, not, never) |

Words per sentence |

Certainty words (always, absolutely) |

Swear words |

Hedge phrases (“I think,” “I believe”) |

These additional language differences buttress what has already been noted. Males categorize their worlds by counting, naming, and organizing the objects they confront. Women, in addition to personalizing their topics, talk in a more dynamic way, focusing on how their topics change. Discussions of change require more verbs.

Finally, one of the most studied dimensions of women’s language concerns hedge phrases, or hedges. Hedges typically start a sentence in the form of a phrase such as “I think that” or “It seems to me” or “I don’t know but …” Consider the meaning of the two following answers to the question

What’s the weather like outside?

I think it’s cold.

It’s cold.

The answer “I think it’s cold,” as opposed to “It’s cold,” tells more than the outside temperature. The “I think” phrase is implicitly acknowledging, “Although there are different views on this—and you may indeed come to a different conclusion—my own personal belief is that it might be cold outside. I could be wrong, of course, and if you have a different sense of the weather, I won’t be offended.” To say “I think,” then, implies that there are multiple perspectives and, at the same time, announces that the estimation of coldness is ultimately an opinion rather than a fact. To say “It’s cold” is to say the weather outside is cold. An indisputable fact. End of discussion.

Consistent with the greater social interests of women, it is not surprising that they are more likely to use hedges than are men. Interestingly, women are just as likely to use hedges when talking with other women as when talking with men.

GENDER, STEREOTYPES, AND COMPUTERS

There is nothing inherently mysterious about the language of women and men. Nevertheless, most of us have been blind to these sex differences our entire lives. I’m no different. Soon after developing the computerized word counting program LIWC, I started analyzing dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of essays, blogs, and other text samples from men and women. One of the first analyses revealed the pattern of effects you have just read about. When I first found that women used I-words more than men, I just ignored the results. Had to be a fluke. Another study, same effects. Another fluke, I thought. It probably took a dozen analyses with very large samples to slap me awake.

The stereotypes we hold about women and men are deeply ingrained. Even within the scientific community, the study of gender differences in language is highly politicized. One group of scientists passionately believes that men and women are essentially the same; another believes that they are profoundly different. Yet others simply don’t want to think about it. But the stereotypes persist. Some believe that women are more emotional and men are more logical or that women talk about others and men talk about themselves. Yet others are convinced that women simply say twice as many words every day as men. Even though most of these beliefs have been debunked by good scientific studies, it is hard to let go of them.

Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the women’s movement awakened the culture to the fact that women and men were not treated equally. A Berkeley linguist, Robin Lakoff, published a stunning book in 1975, Language and Woman’s Place, that pointed out how women and men talked differently. Lakoff argued that men used the language of power and rudeness, while women’s speech tended to be quieter, passive, and excessively polite. In the decades that followed, several studies supported Lakoff’s observations. By the early 1990s, Deborah Tannen, a linguist at Georgetown University, attracted international notice with her book You Just Don’t Understand. Her book, which was on the New York Times bestseller list for over four years, argued that men and women often talk past each other without appreciating that the other sex is almost another culture. Women, for example, are highly attentive to the thoughts and feelings of others; men are less so. Women view men’s speaking styles as blunt and uncaring; men view women’s as indirect and obscure.

Sociolinguists such as Lakoff and Tannen focus on broad social dimensions such as gender, race, social class, and power. Their approach is qualitative, involving recording and analyzing conversations on a case-by-case basis. It is slow, painstaking work. Over the course of a year, a good sociolinguist may analyze only a few interactions. Whereas the qualitative approach is powerful at getting an in-depth understanding of a small group of interactions, the methods are not designed to get an accurate picture of an entire society or culture. This is where computer-based text analysis methods can help. By analyzing the blogs of hundreds of thousands of people, for example, the computer-based methods can quickly determine the nature of gender differences as a function of age, class, native language, region, and other domains. In other words, a relatively slow but careful qualitative approach can give us an in-depth view of a small group of people; a computer-based quantitative approach provides a broader social and cultural perspective. The two methods, then, complement each other in ways that the two research camps often fail to appreciate.

HOW BIG ARE GENDER DIFFERENCES IN LANGUAGE?

Although men and women use words differently, the differences can often be subtle. In one large study of over fourteen thousand language samples, we found that about 14.2 percent of women’s words were personal pronouns compared with only 12.7 percent for men. From a statistical perspective, this is a huge difference. The kind of whopping statistical effect that brings tears of joy to a scientist’s eyes (or at least mine).

But a tear-inducing statistical effect does not always translate into an everyday meaningful effect. Let’s say we find a slow-talking person who speaks at the rate of a hundred words per minute. In any given minute, an average woman should say 14.2 personal pronouns and the average male 12.7. That is, the woman will mention about one and a half pronouns more than the man every minute. These numbers add up over the course of the day. For example, the average man and woman each say about sixteen thousand words a day. In the course of a year, women will say about eighty-five thousand more pronouns than will men. It boggles the mind. But does it matter? Although women are uttering almost 12 percent more pronouns than men, our brains are not constructed to pick up the difference. The average person can’t consciously detect a 12 percent difference and can’t even see the difference in written text. If you are intent on stealth word detection, you need to either count the words by hand or use a computer to do the dirty work.

Although we might not be very good at perceiving the differences in language between men and women, how well do computers do at distinguishing the writing of women from men? Let’s say we saved the text of well over 100,000 blog posts from, oh, I don’t know, 19,320 blog authors who identified themselves by their sex. Imagine that we then trained our computer program to sort the blogs by function-word use into male bloggers versus female bloggers. As you might have guessed, we have done just this. Overall, the computer correctly classifies the sex of the author 72 percent of the time (50 percent is chance). If we also look at the content (in addition to the style) of what people are writing, our accuracy increases slightly to about 76 percent. Note that these guesses are far superior to human guesses, which are in the 55–65 percent accuracy range.

All of these statistics tell us that, on average, women and men use words differently. The differences are subtle and not easily picked up by the human ear. And, of course, it is even more complicated than I’ve suggested. All people change their language depending on the situations that they are in. In formal settings, for example, people tend to use far fewer pronouns, more articles, and fewer social words—meaning most of us speak like prototypical men. When hanging around with our family in a relaxed setting, we all talk more like women. In short, the gender effects that exist in language reflect, to some degree, gender. But the context of speaking probably accounts for even more of our language choices.

AN EAR FOR GENDER: PLAYWRIGHTS AND SCREENWRITERS

As a reader, you probably have a certain fondness for the written word. You can easily spot a passage that is well written versus one that is poorly written. As a teacher, I have long wondered what it takes for someone to become a good writer. Better yet, how does one become a great writer? In his delightful book On Writing, novelist Stephen King argues that with practice and hard work, it is possible for a competent writer to become a good writer. However, no amount of work or training can elevate a good writer to a great one. A great writer, in King’s mind, is a different breed.

A common theme in the writing literature is that a great writer has an uncanny ear for words. The ability to capture dialogue is akin to having perfect pitch for music. World-class dialogue writers seem to intuitively know how words are used by a wide range of characters. Think of some of the leading dialogue writers in plays and movies: Arthur Miller’s stark language in Death of a Salesman, Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve, and most anything by William Shakespeare, Tom Stoppard, Woody Allen, Tony Kushner, and Nora Ephron.

A few years ago, I gave a talk on gender and language and someone asked if playwrights and screenwriters naturally knew how women and men spoke. My wife happens to be a superb professional writer and I thought back to her work and announced with certainty: yes. There were no studies to my knowledge but I would bet a reasonable amount of money that the people who are particularly good at dialogue innately use words that are appropriate for the sex of their characters. The expert had spoken.

That night in my hotel room I checked my computer to see if I had some plays or movie scripts to analyze. I did: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Nora Ephron’s Sleepless in Seattle. Both works had a major male and female protagonist—one script written by a man, the other by a woman. A few hundred keystrokes later, I had an answer. Both Mr. Romeo and Ms. Juliet talk like men, and both Ephron’s main characters talk a lot like women. In Aldous Huxley’s words, this was the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact. But maybe these two authors or scripts were a fluke.

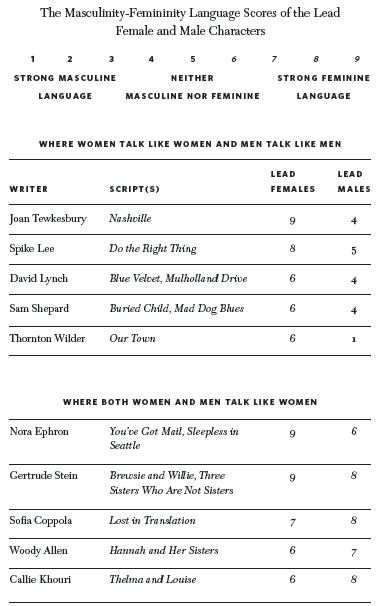

A few days later, I met with one of my graduate students, Molly Ireland. Although Molly knew a lot about psychology, her undergraduate training in literature and philosophy gave her a particularly broad perspective on plays and movies. She eagerly took on a large-scale project that involved analyzing over 110 scripts from more than 70 different playwrights and screenwriters. Such a project could answer several questions. Do writers differ in their abilities to capture the language of women and men? Does capturing the voice of the sexes vary depending on the specific play or movie? That is, one could imagine that a writer might have a sensitive leading man talk like a woman in one movie and like a macho man in another.

Fortunately, we have conducted several studies over the years where we have asked hundreds of people to wear a tape recorder as they go about their daily lives. We have also collected language samples from interviews, lab studies, and other sources. These transcripts have given us a base of thousands of conversations of men and women. Using these data, we can compare the ways that real males and females talk with the ways that leading characters in literature talk.

The results were fascinating. To make the results a bit simpler, Molly and I converted the statistics to a nine-point masculinity-femininity language scale. A score of 1 means that the lead character is speaking like a super-male. You know how super-males talk—lots of articles and prepositions, very few pronouns, social words, or cognitive words. A score of 9 means that the character talks like a super-female—essentially the opposite pattern of the super-male. And a score of 5 means the character’s language is not sex linked.

Each of the tables gives a sense of the ways different authors portray their main characters. Thornton Wilder, in Our Town, tracks the lives of several characters, including Emily Webb. We see Emily as an eager high school student who later falls in love with Joe. After dying in childbirth, Emily appears one final time in the graveyard after she has just gone back in time and watched a scene from her childhood. When she returns to her seat in the cemetery in the final scene, she talks with some of the other dead souls about the shock of watching her early family life.

EMILY: I didn’t realize. So all that was going on and we never noticed. Take me back—up the hill—to my grave. But first: Wait! One more look … Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?—every, every minute?

STAGE MANAGER: No. The saints and poets, maybe—they do some.…

EMILY: Oh, Mr. Stimson, I should have listened to them.

SIMON STIMSON: Yes, now you know. Now you know! That’s what it was to be alive. To move about in a cloud of ignorance; to go up and down trampling on the feelings of those … of those about you. To spend and waste time as though you had a million years. To be always at the mercy of one self-centered passion, or another. Now you know—that’s the happy existence you wanted to go back to. Ignorance and blindness.…

EMILY: They don’t understand, do they?

MRS. JULIA GIBBS: No, dear. They don’t understand.

…

STAGE MANAGER: Most everybody’s asleep in Grover’s Corners. There are a few lights on: Shorty Hawkins, down at the depot, has just watched the Albany train go by. And at the livery stable somebody’s setting up late and talking. —Yes, it’s clearing up. There are the stars—doing their old, old crisscross journeys in the sky. Scholars haven’t settled the matter yet, but they seem to think there are no living beings up there. Just chalk … or fire. Only this one is straining away, straining away all the time to make something of itself. The strain’s so bad that every sixteen hours everybody lies down and gets a rest. Hm … Eleven o’clock in Grover’s Corners. —You get a good rest, too. Good night.

If you haven’t seen or read Our Town in a while, it is a remarkable piece of work. Even in this brief scene, the women—Emily and her mother-in-law Julia Gibbs—focus on their own feelings and those of others. The men, Simon Stimson and the stage manager, use virtually no pronouns and describe the world in nice objective manly ways. Wilder’s men do indeed talk like prototypical men and his women talk like prototypical women.

Compare Wilder’s writing with Callie Khouri’s screenplay Thelma and Louise. Through a series of haunting misadventures, the two main characters, Thelma and Louise, find themselves running from the law after shooting a would-be rapist. The primary investigator, Hal, talks with Louise by phone and pleads for her to give herself up:

LOUISE: Would you believe me if I told you this whole thing is an accident?

HAL: I do believe you. That’s what I want everybody to believe. Trouble is, it doesn’t look like an accident and you’re not here to tell me about it … I need you to help me here.… You want to come on in?

LOUISE: I don’t think so.

HAL: Then I’m sorry. We’re gonna have to charge you with murder. Now, do you want to come out of this alive?

LOUISE: You know, certain words and phrases just keep floating through my mind, things like incarceration, cavity search, life imprisonment, death by electrocution, that sort of thing. So, come out alive? I don’t know. Let us think about that.

HAL: Louise, I’ll do anything. I know what’s makin’ you run. I know what happened to you in Texas.

What makes Khouri’s men so interesting is that they actually speak more like women than do the women. Hal’s frequent use of pronouns and low use of articles points to his deep interest in other people as opposed to concrete objects. Another important feature of the movie is that all the men—including the role played by Brad Pitt—have a feminine speaking style. At the same time, none would be considered remotely effeminate in their actions.

Just the opposite pattern can be seen in Quentin Tarantino’s script Pulp Fiction. Perhaps the most traditionally feminine character in the movie is the young French woman, Fabian, who is involved with Butch (played by Bruce Willis). Despite her girl-like appearance and childlike voice, Fabian’s words are decidedly masculine. In this scene, Butch has just returned from throwing a boxing match and accidentally killing his opponent (life is not easy for any Tarantino character). Fabian is not aware of what has happened and announces that she has decided that she would like to have a potbelly.

FABIAN: A pot belly. Pot bellies are sexy.

BUTCH: Well you should be happy, ’cause you do.

FABIAN: Shut up, Fatso! I don’t have a pot! I have a bit of a tummy, like Madonna when she did “Lucky Star,” it’s not the same thing.

BUTCH: I didn’t realize there was a difference between a tummy and a pot belly.

FABIAN: The difference is huge.

BUTCH: You want me to have a pot?

FABIAN: No. Pot bellies make a man look either oafish, or like a gorilla. But on a woman, a pot belly is very sexy. The rest of you is normal. Normal face, normal legs, normal hips, normal ass, but with a big, perfectly round pot belly. If I had one, I’d wear a tee-shirt two sizes too small to accentuate it.

BUTCH: You think guys would find that attractive?

FABIAN: I don’t give a damn what men find attractive. It’s unfortunate what we find pleasing to the touch and pleasing to the eye is seldom the same.

That Quentin Tarantino’s characters use the language of males might not be too shocking for serious moviegoers. But what about the Bard himself, William Shakespeare? In perhaps the most famous scene of Romeo and Juliet, the young lovers proclaim:

ROMEO: What light through yonder window breaks? It is the East, and Juliet is the sun! Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon, Who is already sick and pale with grief That thou her maid are far more fair than she. Be not her maid, since she is envious. Her vestal livery is but sick and green, And none but fools do wear it. Cast it off. It is my lady; O, it is my love! O that she knew she were! She speaks, yet she says nothing. What of that? Her eye discourses; I will answer it. I am too bold; ’tis not to me she speaks. Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven, Having some business, do entreat her eyes To twinkle in their spheres till they return. What if her eyes were there, they in her head? The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars As daylight does a lamp; her eyes in heaven Would through the airy region stream so bright That birds would sing and think it were not night. See how she leans her cheek upon her hand! O that I were a glove upon that hand, That I might touch that cheek!…

JULIET: O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou Romeo? Deny thy father and refuse thy name; Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love, And I’ll no longer be a Capulet.… ’Tis but your name that is my enemy. Thou art thyself, though not a Montague. What’s Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot, Nor arm, nor face. O, be some other name Belonging to a man. What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other word would smell as sweet. So Romeo would, were he not Romeo called, Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name; And for thy name, which is no part of thee, Take all myself.

We can feel the yearning and innocence of Romeo and Juliet, the lightness and openness. A cursory reading would never reveal that both—especially Juliet—are expressing themselves the ways that males tend to do. Both use I-words at low levels, use a below-average number of personal pronouns in general, and have above-average article usage, especially for such a personal and intimate setting.

Shakespeare and Tarantino are males and write like males. Their male and female characters use function words the ways males do. The two writers may share the same stealth word usage, but they clearly differ in the content and breadth of what they write. Shakespeare is of interest because he brilliantly conveys real-life themes and concerns women have. But his use of function words, much like Tarantino’s, suggests that he fails at getting inside the minds of women.

Do these things matter from the audience’s perspective? Yes, but in a subtle way. Recall Deborah Tannen’s analogy of sex differences being akin to cultural differences. Most of us can read, say, Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and come away with an appreciation of Raskolnikov’s tortured thoughts of murdering the pawnbroker. We can do this even without speaking Russian or knowing nineteenth-century St. Petersburg culture. Of course, the St. Petersburg native reading Dostoyevsky’s work in 1866 would undoubtedly possess a more intimate understanding of the book than would twenty-first-century native English speakers. By the same token, a woman scriptwriter’s depiction of a man’s way of speaking may mischaracterize the ways males actually speak, but if the content is compelling, we will probably not notice it.

SEX DIFFERENCES IN LANGUAGE: THE POSSIBLE ROLE OF TESTOSTERONE

Women and men use language differently, tend to talk about different topics, and ultimately may represent two subcultures of humans. Clearly, girls and boys are socialized differently, which may account for many of the language differences. Is it also possible that our interests may be influenced by our hormones? And if our interests are hormone related, perhaps our hormones may guide our everyday language use.

Beyond the anatomical differences of women and men, the two sexes have strikingly different hormonal profiles. Compared to men, women have very high levels of estrogen—a family of hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle, the development of female sex organs, breasts, and pubic hair, as well as aid in the ability to become pregnant. For men, the hormone testosterone is associated with the development of male sex organs and secondary sex characteristics such as facial hair. Women also secrete testosterone but at much lower levels than men, just as men have low levels of estrogen.

For a variety of reasons, both men and women occasionally undergo testosterone therapy, whereby they are given periodic injections of the hormone. What would happen to their language during times when their testosterone levels were high versus when they were low? Through an odd series of events, I was able to answer the question.

Around the year 2000, I was contacted by Professor James Dabbs, a world-renowned expert on the psychological correlates of testosterone. A tall, distinguished southerner with a polite, regal bearing, Jim had measured testosterone levels of murderers, lawyers, actors, priests, academics, and others—always with a twinkle in his eye. Much of his work examined the links between aggressive behaviors and testosterone levels. (During one serious conference on hormones and behavior, Jim started his talk by looking around the packed lecture hall and snorting, “There’s not enough testosterone in this entire room to rob a single liquor store.”)

Jim had received a letter from a biological female who was undergoing therapy to become male, a female-to-male (FTM) sex change, or, more accurately, gender reassignment. The person, GH, was twenty-eight years old and had been involved in gender reassignment for three years. In addition to a double mastectomy, GH received injections of testosterone every two to four weeks. GH had read about Jim’s research and wanted to know if he would like to study GH’s diaries, which he (GH) had been keeping for several years. Knowing that I studied language, Jim felt I could examine the effects of testosterone on function words.

GH was articulate and a prolific writer. He provided my research team with two years of his diaries along with a detailed record of his testosterone injections. While we were transcribing GH’s diaries, I was invited to give a series of talks in Boston. One night, I found myself in a bar talking to a gentleman who happened to be an anthropologist. In the midst of our conversation, I mentioned the GH project. My new anthropologist friend was silent for a minute and finally said that he, too, was taking testosterone injections on the advice of his physician. He was sixty years old and had been taking testosterone for four years in an attempt to restore his upper-body strength. “Really?” I asked innocently. “Do you have a record of your injections?” Yes. “By any chance do you keep a diary?” No, but he was willing to let me analyze all of his outgoing e-mails for the previous year.

The analyses were straightforward. For both GH and the anthropologist, the words that they wrote each day were analyzed using the LIWC computer program. The word categories were then compared against the number of days since each person’s last testosterone injection. The idea was that as time passed since the last injection, each person’s testosterone levels would drop.

The similarity of effects for the two people was striking and the overall results promising. Whether their testosterone went up or down, no predictable changes were seen in their use of articles, prepositions, nouns, verbs, and negative emotion words. However, there was one fascinating and reliable difference—in social pronouns (including words like we, us, he, she, they, and them). As testosterone levels dropped, they used more social pronouns. Think what this means: Both GH and the anthropologist inject themselves with testosterone and they now focus on tasks, goals, events, and the occasional object—but not people. And then, as the days wear on, they awake each morning and notice that there are other human beings around. And these human beings are interesting and worth talking about and talking to. And then, a few weeks later and another injection, and voilà! They’re cured. No more worrying about others.

This study gives us a glimpse of how testosterone may psychologically affect people. Prior to receiving their results, I asked both participants how they felt that testosterone affected their language. GH was certain that the injections gave him more energy, made his mood more positive, and stimulated more thoughts of sex, aggression, sports, and traditional masculine things. The anthropologist, on the other hand, was adamant that testosterone had absolutely no psychological effect on him whatsoever. Both were wrong.

What does a study like this tell us about sex differences and the biology of function words? Only a little, I’m afraid. Injections of testosterone did not change GH’s sex or the anthropologist’s masculinity. There is no evidence that this hormonal assault had any effects on the ways either person understood, thought about, or categorized their world. It is significant, for example, that not a hint of changes in articles, nouns, verbs, cognitive words, or prepositions occurred. Finally, this was a study on only two people in unusual circumstances, meaning we should be cautious in generalizing the findings.

On a broader level, however, the testosterone study, along with the various gender-language projects, tells us a little about the ways men and women see and understand their worlds. Men are less interested in thinking and talking about other people than are women. The effects may be influenced by testosterone, but quite frankly, the testosterone findings are too preliminary to make grand pronouncements just yet.

That there are differences in social interests between women and men isn’t exactly news. However, the fact that men consistently use more articles, nouns, and prepositions is news. OK, maybe it’s not going to be on CNN’s Headline News. But it is news because these language differences signal that men tend to talk and think about concrete objects and things in highly specific ways. They are naturally categorizing things. Further, the use of prepositions signals that the categorization process is being done in hierarchical and spatial ways. Think about when we use prepositions:

The keys to the trunk of the car from Maria are next to the lamp under the picture of the boat painted by your mother.

The words to, of, from, next to, under, of, and by specify which and whose keys and exactly where they are in space. There is a hierarchical structure in the sense that these are not just any keys. Rather, they are part of the category of trunks, which are part of the category of cars from Maria. Similarly, the location of the keys is specified in both horizontal (next to) and vertical (under) planes. Statistically, it is much more likely that a sentence such as this would be uttered by a man than a woman. It’s not that the man has a penchant for prepositions and nouns—rather a man naturally categorizes and assigns objects to spatial locations at rates higher than women.

WORDS OF WISDOM: LANGUAGE USE OVER THE LIFE SPAN

In most large surveys, researchers ask three questions: sex, age, and social class. Social class, which we will discuss soon, is usually asked indirectly with questions linked to race, education, or income. Why do survey makers want to know your sex, age, and social class if studying your political attitudes or buying behaviors? Because these three variables predict a stunning amount about people. If I know your sex, age, and social class, I can make surprisingly accurate guesses about your movie and music preferences, your religious and political views, your physical and mental health, and even your life expectancy.

These three demographic factors are also linked to language use. In many ways, the connections between language and age are more interesting than the connections to gender. If you are born a woman, the odds are very, very high that you will remain a woman your entire life. However, if you are born a baby, the odds are astronomically high that you won’t remain one very long.

That our language—more specifically our use of function words—changes over the life span is, in some ways, surprising. But less so if you consider how our goals and life situations evolve, as do our bodies. As we get older, we change in the ways we orient to our friends and family, sex, money, health, death, and dozens of other life concerns.

Our personalities shift as well. Studies with thousands of people indicate that how we feel about ourselves is generally quite positive up until about age twelve. From about thirteen to twenty, our self-esteem levels drop to some of the lowest levels in our lives. Thereafter, to around the age of seventy, most people’s self-esteem gradually increases. In fact, by around the age of sixty-five, many of us feel as good about ourselves as when we were nine years old—which is as good as it ever gets. And then, self-esteem tends to drop during the last few years of life. Other studies, based on 5,400 pairs of twins, find that as people get older, they become less outgoing, more emotionally stable, and a bit more impulsive.

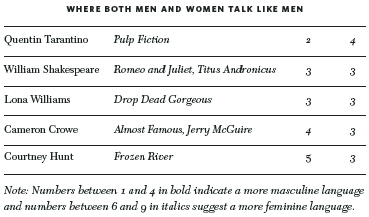

The personality research is at odds with the bleak stereotypes of older people as being lonely, selfish, rigid, and bitter. Some of the more promising research that combats these stereotypes is being conducted by Laura Carstensen and her colleagues at Stanford University. She finds that as people age, emotion becomes a more important part of life. With greater attention to emotional states, people learn to regulate their emotions more effectively, resulting in greater happiness and fewer negative feelings. Although people over the age of seventy tend to have fewer friends, their social networks become stronger.

A fitting observation by the main character, Lloyd, in the Farrelly brothers’ classic film Dumb and Dumber says it all. After asking an elderly woman to guard his possessions for a few minutes, Lloyd remarks, “Thanks. Hey, I guess they’re right. Senior citizens, although slow and dangerous behind the wheel, can still serve a purpose. I’ll be right back. Don’t you go dying on me!” The elderly woman cheerfully snatches everything Lloyd owns.

How does language change as people age? We have tested this in several ways. The first was to go back to the giant blog project where we analyzed the collected posts of over nineteen thousand bloggers. The blog site that we “harvested” in 2004 was made up of people who were, on average, about twenty years old. We split the sample into three age groups: adolescent (ages thirteen to seventeen), young adult (ages twenty-three to twenty-seven), and adult (ages thirty-three to forty-seven). Despite the restricted age range, the three groups used emotion and function words very differently. Teens used personal pronouns (I, you), short words, and auxiliary verbs at very high rates. The older the people became, the more they used bigger words, prepositions, and articles.

We also conducted a systematic analysis on people who took part in one of several dozen expressive writing studies. As you recall from the first chapter, I’ve long been involved in studies where we ask people to write about deeply personal and oftentimes traumatic experiences. Over the years, researchers from labs around the world have sent me the writing samples from studies they have conducted. For the aging project, I teamed up with Lori Stone Handelman, a brilliant graduate student who later became a highly respected book editor in New York. Lori and I analyzed data from over 3,200 people who participated in one of 45 writing studies from 17 different universities. Although the average person in the studies was about twenty-four years old, the ages ranged from eight to eighty years old.

As you might imagine, people wrote about a wide array of topics—from sexual abuse and drug addiction to the death of a pet to not making the high school football team or cheerleading squad. Many of the essays were heartbreaking. For most, there was the sense that people put their soul into writing their stories.

Computer analyses of the texts yielded large and sometimes unexpected findings. When writing about emotional topics, the younger and older participants used strikingly different words.

Perhaps more impressive was the emotional tone of the young versus older writers. Consistent with the survey research, older people used more positive emotion words and younger people expressed more negative feelings. The differences became apparent by the age of forty but exploded among the oldest age group.

YOUNGER WRITERS |

OLDER WRITERS |

Personal pronouns (especially I) |

Articles, nouns, prepositions |

Time references |

Big words |

Past-tense verbs |

Future-tense verbs |

Cognitive words (insight words) |

What makes these findings so intriguing is that all people were asked to write about some of the most troubling experiences of their entire lives. Younger people could dredge up an impressive number of dark words to express their pain. As writers got older and older, their negative emotion vocabulary diminished and their positive emotion word count skyrocketed. As you can see on the next page, the very youngest writer in this sample, who was eight years old, had a very different approach to the subject of his emotional story (Randy) than the oldest participant, who was dealing with cancer:

Eight-year old elementary school student: My enemy is Randy he makes me mad. Outside he calls me names, he ignores me, he does not stop bothering me, so I call him names when he starts. He does not stop so I start and get him back he makes me mad so I make him mad so I try to ignore him but he keeps making me mad … My mom says he is a bad influence.

Eighty-year old retiree. I am 80 years old, but I try to keep busy and go about life as though there is no ending. Sure I am not as fast or move as quick as I once did, but I do not feel it was the fault of the cancer and I try to do the best I can with what I’ve got. When negative thoughts try to creep in my thoughts I immediately try to replace them with positive thoughts of how lucky I am to still be here. For the 38 treatments I drove the car myself every morning alone and had a good chance of meditation and this is where I found my positive attitude from seeing the beauty of nature and changing of the seasons.

Would you rather be eighty years old or eight? After reading these essays, the answer is not as simple as you might have thought. You get a greater appreciation of Laura Carstensen’s argument that the older we get, the better we are able to regulate our emotions. At the same time, aging allows us to look at the world in a more detached way.

One concern that many life-span scientists have is that differences in language between, say, a group of seventy-year-olds and a group of forty-year-olds may not reflect the effects of age. Rather, all the seventy-year-olds have gone through shared life experiences that the forty-year-olds haven’t. For example, in some of the studies that were run in the early 1990s, all those who were in their seventies had grown up without television and had lived through World War II. Those in their forties generally had lived with television all their lives and were part of the baby boom generation. Maybe seventy-year-olds are just happy because they didn’t have television growing up. Probably not, however.

One way that we bypassed this problem was to study the collected works of ten novelists, poets, and playwrights over the last four centuries who wrote extensively over the course of their lives. With this group of authors, we simply tracked their language use as they got older. Overall, eight of the ten authors showed the same age-related language patterns that we found in our other projects (the two exceptions were Louisa May Alcott and Charles Dickens).

A nice example is from the writings of the British novelist Jane Austen. Austen was born in 1775 and died at the age of forty-two. Her first work was written when she was twelve and she continued writing until her death. Her original manuscripts, including short novels, letters, and poems, were later published in a book called Juvenilia; her last book, Sanditon, was not quite finished when she died. Compare the first paragraphs of her first and last novels.

Jack and Alice: A Novel (from Juvenilia)

Mr Johnson was once upon a time about 53; in a twelve-month afterwards he was 54, which so much delighted him that he was determined to celebrate his next Birth day by giving a Masquerade to his Children and Friends. Accordingly on the Day he attained his 55th year tickets were dispatched to all his Neighbours to that purpose. His acquaintance indeed in that part of the World were not very numerous as they consisted only of Lady Williams, Mr and Mrs Jones, Charles Adams and the 3 Miss Simpsons, who composed the neighbourhood of Pammydiddle and formed the Masquerade.

Sanditon

A Gentleman & Lady travelling from Tunbridge towards that part of the Sussex Coast which lies between Hastings & E. Bourne, being induced by Business to quit the high road, & attempt a very rough Lane, were overturned in toiling up its long ascent half rock, half sand. - - - The accident happened just beyond the only Gentleman’s House near the Lane - - - a House, which their Driver on being first required to take that direction, had conceived to be necessarily their object, & had with most unwilling Looks been constrained to pass by.

Even at the age of twelve (and she may have been as old as fifteen), Austen was precocious. Nevertheless, the writing samples betray clues of the author’s age. In Sanditon, Austen uses far more prepositions, nouns, and cognitive words (e.g., induced, quit, overturned, constrained). The young Austen uses more personal pronouns and references to time (e.g., time, month, day). Although the young Austen uses an inordinate number of large words for a person of any age, it’s clear that her thinking is far less complex than the older Austen’s.

Austen’s age-related language changes map those of the poets Wordsworth, Yeats, Robert Graves, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, as well as fellow novelist George Eliot and playwright Joanna Baillie. Shakespeare’s profile is a bit complicated but even he shows the same general patterns.

One final note of interest about the language of age and sex: You may have noticed that older people often use function words like men and younger people tend to use them like women. This isn’t some kind of statistical fluke. These patterns hold up across cultures, languages, and centuries. Interestingly, it’s not that women start to talk like men and men just stay the same. Rather, men and women usually have parallel changes. For example, at ages eight to fourteen, about 19 percent of girls’ words are pronouns, compared with 17 percent for boys. By the time they reach seventy, the rates drop to 15 percent for women and 12 percent for men.

We will return to the possible reasons for these patterns after discussing social class differences, which, as you will see, overlap with some sex and age effects.

SOCIAL CLASS AND LANGUAGE

From the very beginning of my education, I was always taught that in the United States we do not have social classes. England and India did, of course. But not the U.S. In graduate school in social psychology, there were often discussions of racial differences and inequality in the United States but never anything about social class. That’s right, the U.S. didn’t have social classes. By the time I was a young faculty member studying physical health, most conferences I attended in the U.S. would include presentations demonstrating large racial differences in blood pressure and other diseases, smoking and obesity and other health behaviors, and life expectancy. Nothing about social class. Well, you know why.

By the early 1990s, I was attending more and more international conferences. If the speakers were from Europe, their graphs and tables always included class information but not race. The Americans were just the opposite. By the mid-1990s, however, something shifted. Statisticians started remarking that the effects of social class in the United States were often stronger than the effects of race. Indeed, in the last decade, a dizzying number of studies have shown powerful effects of class on smoking, drinking, depression, obesity, and every physical and mental health problem you can imagine.

Social class is generally measured by years of education that people have completed and their yearly income. You might think that lower social class is associated with health problems because poorer people don’t have access to health care. In fact, the exact same social class effects are found in Sweden and other countries where health care is universal. Social class is linked to almost everything we do—the foods we buy, the movies we see, the people we vote for, and the ways we raise our children. And, predictably, the ways we use function words.

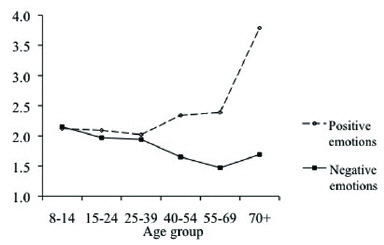

Over the last forty years, a smattering of studies have pointed to social class differences in language development, vocabulary, and even language patterns in the home. None to my knowledge have examined language differences among large samples of adults. Recently, my colleagues David Beaver, a linguist, and Gary Lavergne, a researcher in the University of Texas at Austin (UT-Austin) Office of Admissions, and I teamed up to study the admissions essays that high school students write in order to gain access to college. UT-Austin is a selective undergraduate institution and recruits about seven thousand top students each year. In addition to writing two essays, applicants must also complete a large number of surveys in order to be considered for admission. Among other things, students are asked to supply information about their families’ social class—including education of parents and estimated parental income. Examining the data for four consecutive years allowed us to study the social class–language connection with over twenty-five thousand students.

The table on the next page should be somewhat familiar. Students coming from higher social classes tended to use bigger words, more articles (and nouns), and more prepositions. Students from lower social classes tended to be more personal in their admissions essays, using more pronouns, auxiliary verbs, present-tense verbs, and cognitive mechanism words (many of which are associated with hedges).

Statistically, these are very large effects. The patterns are identical for males and females, and younger and older applicants. Also, these are all smart and motivated students. Why are there social class differences in function word use? Clearly, something about the students’ upbringing and life experiences is influencing their word choices.

One promising idea is that there are differences in language use within families of differing social classes from the beginning. There is some preliminary research to support this idea. Perhaps the most cited and overinterpreted study was one done by Betty Hart and Todd Risley in the mid-1980s. In their study, thirteen professional families, twenty-three working-class families, and six families on welfare were tape-recorded in their midwestern homes for an hour once a month for over two years. When the study started, most of the children were under a year old. The tape recordings were carefully transcribed and all the words of the children and adults were counted.

The authors discovered that children in the poorest families were exposed to fewer than half as many words as those from the professional families. Those in the working-class families were in between. By the end of the study, children in the professional families had vocabularies (based on the recordings) that were twice as large as those of the welfare families’ children. On the surface, this was an impressive study. However, even the authors agree that the results should be interpreted with caution. For example, there were only six families in the lowest social class group. In addition, all the professional families had at least one parent who was a faculty member and almost all were white. In all likelihood, the professional families felt quite comfortable having students in their house every month recording what they said. The welfare families, on the other hand, were all African-American and likely had a very different view of the study than those in the professional families. For example, the lower-class families may well have been more suspicious of the experimenters and may have avoided talking on the recording days.

It is likely that the verbal experiences of children brought up in lower-class families are different from those brought up in wealthier, more highly educated families. Why this might result in different patterns of function word usage may be related to issues of power and status.

SPEAKING OF SEX, AGE, AND SOCIAL CLASS: THE SOUND OF POWER

In this chapter, two groups of words repeatedly emerge. The first, which we will call the noun cluster, includes articles, nouns, prepositions, and big words. The second will be referred to as the pronoun-verb cluster. It is composed of personal and impersonal pronouns (especially first-person singular), auxiliary verbs, and certain cognitive words frequently linked to hedge phrases. Men, older people, and higher social classes all use noun clusters at high rates; women, younger people, and lower social classes use pronoun-verb clusters at high rates. Most simple hypotheses to explain these differences fall apart at some point. For example, one might argue that people who are more verbal might be drawn to, say, pronoun-verb words. This might be true for women and older people but not lower social classes. Perhaps those high in noun clusters simply read more and are exposed to more words—again, this might work for older people and higher social classes but not men.

The simplest explanation is that people higher in power and status are drawn to noun clusters and people lower in power and status rely on pronouns and verbs. For the sake of argument, why would those with more authority use more noun-related words? And, equally important, why would lower levels of power be associated with the use of more verbs and pronouns?

One solution is to consider what power and status buy. Adam Galinsky, a researcher in the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, has conducted a number of studies where people either think they have power in a group or think they don’t. If they believe they control their fate, they are much more likely to make decisions on their own and ignore others’ ideas. Those with less power are easily swayed by others. In short, if you don’t have power in a situation, it is in your best interests to pay attention to others. But if you are the boss, you should pay close attention to the task at hand.

As noted in the last chapter, when people are task focused, they don’t pay attention to themselves. Most tasks, in fact, require a clear awareness of the objects, events, and concrete features that are necessary to accomplish the task goals. Much like the two people with the artificially high testosterone levels, task-focused people are able to make decisions without human relationships getting in the way.

While signaling less status, the use of pronouns and verbs also suggests that speakers are more socially oriented. Most pronouns are, by definition, social. Words such as we, you, she, and they tell us that the speaker is aware of and thinking about other human beings. First-person singular pronouns are a bit different in that they signal self-attention. Indeed, in later chapters, we summarize evidence suggesting that humans (and nonhuman mammals) tend to pay more attention to themselves in settings where they are subordinate to more powerful others. Why verbs in general and auxiliary verbs in particular may signal lower power is not entirely clear. Auxiliary verbs (such as is, have, do) are generally part of a passive way of speaking: “He was hit by the ball” as opposed to the more active “The ball hit him.”

The similarity in word use across age, sex, and social class is only a small part of the puzzle of function words and social psychology. Being a woman or a man, young or old, rich or poor is only a small part of our identities. We have just glimpsed the language of who we are. In the next chapter, we dig more deeply into the individual psychology of each of us.