CHAPTER 5

Who said there’s no crying in football? [New York] Jets coach Rex Ryan … in the wake of the previous day’s devastating 24–22 loss to the Jaguars, delivered an impassioned speech to his players that was so emotionally-charged it brought him to tears.… “He didn’t bash us at all; he was just very emotional … he was crying,” right tackle Damien Woody told The Post. “Rex believes in our team so much I can’t even put it into words and it would be a shame if we didn’t capitalize on our opportunity.”

“I was a little upset to see him that way,” cornerback Darrelle Revis told The Post. “I’m upset for the same reasons he’s upset.”

Asked if he’s ever been a part of a meeting with such high-powered emotions, Revis said: “No, I haven’t been a part of a meeting where a coach cried like that.… In the future, I hope there are more tears of joy than the one this morning.”

—MIKE CANNIZZARO, New York Post, November 17, 2009

All signs point towards trouble for [the New York Jets] this week, as Coach Rex Ryan cried as he addressed his team on Monday, feeling so overwhelmed with emotions. Staged or not, Ryan’s using tears to motivate and bring his team together is the official signal that the wheels have come off.

—SAM HITCHCOCK, NewJerseyNewsroom.com, November 20, 2009

WHEN PEOPLE BEHAVE emotionally, it gets our attention. An adult football coach crying is important information for his team, his opponents, and the football-watching public at large. The original New York Post article suggested that after Coach Ryan’s emotional display, his team was ready to take the next bus to Boston to better prepare for their upcoming game with the New England Patriots. The article a few days later from the respected NewJerseyNewsroom website viewed the same emotional display as evidence that the team was headed for disaster. And, indeed, it was. The following Sunday the Jets were crushed by the Patriots 31–14. No tears were reported the following week.

Emotions change the ways people see and think about the world. They can motivate people to work harder or cause them to give up in despair. Emotions can broaden our perspectives or restrict them by causing us to ruminate about the same topics over and over. Emotions guide our thinking and affect the ways we talk and get along with others. Not only do we need to know our own emotions, we need to be able to read other people’s emotions to understand what they are thinking and planning to do.

Reading other people’s emotions is usually easy if they are crying, screaming, or laughing hysterically. At other times emotions are conveyed more subtly through facial expressions, tone of voice, or nonverbal behaviors. Much of the time, however, people may be feeling one thing but not conveying it. All of us have had the experience of not knowing if our date, parent, teacher, boss, or client likes us or not. In our close relationships, someone may have failed to pick up on important emotional cues that may have damaged the relationship. In reading others’ e-mails, IMs, tweets, or letters, most of us have missed an emotional cue that the other person may have been intending to send.

The central question of this chapter is how can we detect people’s emotions through their words. On the surface, this sounds like a simple task. If people are happy, they should use happy words. If sad, they should use sad words. If only it were this easy. Counting emotion words is a fine start to measuring feelings but these approaches miss the central point: Emotions affect the ways people think. If we could just come up with a way to measure the ways people think, we could come up with a richer way to study and understand emotions. There is just such a way. Function words do a fine job of tracking people’s thinking styles. It should come as no surprise that these same words can provide insight into people’s emotional states as well.

DIFFERENT EMOTIONS, DIFFERENT WAYS OF THINKING

A good starting point is to consider three distinct emotions: happiness, sadness, and anger. We all agree that these are common emotional states that have their own distinct physical and psychological feelings. These different emotions also cause us to look at the world differently. When thinking about emotions and words, it can be instructive to see how poets write. After all, poets spend much of their time writing about their emotional reactions. Do poets use function words differently when writing about happiness, sadness, and anger? Look at some of the work by Edna St. Vincent Millay, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Writing in the first half of the twentieth century, Millay was celebrated as a free spirit who wrote powerfully about love, loss, and relationships. Compare the ways she uses words in lines from the poems on the following page.

The examples from Millay illustrate what researchers have found. When writing about positive experiences people tend to use we-words at particularly high rates. People who are happy are also more specific, relying on concrete nouns and references to particular times and places. Other studies find that positive moods change people’s perspectives so that they look at the world in a more open way—sometimes referred to as the broaden-and-build way of thinking. Sadness generally causes people to focus inwardly. Pronouns tend to track people’s focus of attention, and when in great emotional or physical pain, they tend to use I-words at high rates. Sadness, unlike most other emotions, is associated with looking back in the past and into the future. In other words, people tend to use past- and future-tense verbs more when they are sad or depressed compared to other strong emotions.

Although classified as a negative emotion, anger has a completely different profile than sadness. When angry, people focus on others and rarely themselves. In addition to using high rates of second-person (e.g., you) and third-person (he, she, they) pronouns, angry people talk and think in the present tense.

When events happen to us that cause us to feel sad or angry, we tend to try to understand why they occurred. We use cognitive words that reflect causal thinking and self-reflection. Not true for positive emotions such as pride and love. When happy and content, most of us are satisfied to let the joy wash over us without introspection. In other words, negative feelings make us thoughtful; positive emotions make us blissfully stupid.

Most of the studies that have examined transient emotions in the laboratory have relied on asking college students to write about powerful events that had elicited feelings of happiness, sadness, or anger. The lab studies serve as a helpful road map by which to understand how we all feel and express emotions in the real world.

PRONOUNS AND MISERY: THE LANGUAGE OF SUICIDAL POETS

In any given year, over 5 percent of all adults experience a major depression. Depressive episodes are associated with physical health problems, breakdowns in people’s social and work lives, and greater risk of suicide. A number of factors are known to influence the likelihood of depression, including major life upheavals, genetic predispositions, and social isolation. One particularly prominent theory of depression argues that when people become depressed, they tend to focus on their own emotions at a pathological level. They ruminate on their feelings of anxiety, sadness, and worthlessness while paying less and less attention to the world around them.

Recall that pronouns reflect people’s focus of attention. Given that depression causes people to look inward, it follows that a depressive episode would be associated with higher rates of self-referencing pronouns, especially first-person singular pronouns such as I, me, and my. Several studies have found this. The more depressed a person is, the more likely he or she will use I-words in writing or speaking. Most striking is that use of I-words is a better predictor of depression among college students than is the use of negative emotion words.

Depression rates are particularly high among writers, most notably for successful poets. Recent studies indicate that published poets die younger than other writers and artists and as many as 20 percent commit suicide. Although the job of writing poetry may be stressful, a more compelling explanation is that depression-prone individuals are drawn to writing poetry, in part, to try to understand their mood swings. This is especially true for a form of depression called bipolar depression, sometimes referred to as manic depression. Bipolar disorder is especially toxic because it has a clear genetic basis and often catapults people through extreme mood swings without any apparent cause. Unlike other forms of depression, people diagnosed with bipolar disorder are much more likely to commit suicide.

Kay Redfield Jamison, a respected scientist at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, has written extensively on the close link between the artistic temperament and bipolar disorder. In her research, she finds that a disproportionate number of poets have symptoms consistent with bipolar disorder, which she discovered through their memoirs; reports from family members, friends, biographers; or the authors’ poetry. Would it be possible to identify bipolar disorder and suicide proneness through the computer analysis of the poets’ published works? Working with Shannon Stirman, who is now a clinical psychologist, we examined the published poetry of eighteen poets, nine of whom committed suicide. We discovered that suicidal poets used far more I-words in their poetry than nonsuicidal poets. Particularly striking was that the two groups of poets did not differ in their use of negative emotion words. Although this was a small sample of poets, the effects were statistically impressive.

As we started looking more closely at the language of the suicidal and nonsuicidal poets, something caught our eyes. The suicidal poets, in using I-related pronouns, seemed to be psychologically close to their sadness and misery in ways that the nonsuicidal poets were not.

For example, consider the first line of Sylvia Plath’s well-known poem “Mad Girl’s Lovesong” where she is mourning the loss of love: “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my lids and all is born again. (I think I made you up inside my head.)”

Compare her sadness with the words of the well-respected poet Denise Levertov in the first line of her poem, “The Ache of Marriage”: “The ache of marriage: thigh and tongue, beloved, are heavy with it, it throbs in the teeth.”

Although both poems deal with a similar topic, Plath’s use of I suggests that she is embracing her loss. Levertov, on the other hand, seems to be holding her pain away at arm’s length—almost as if she is looking at it from a more distant (and safer) third-person perspective. Indeed, as one reads the collected works of these two authors, it is apparent how the two differ in owning or embracing their feelings of loss, alienation, and depression. Plath may be the more popular poet for this reason. With the tool of first-person singular pronouns, she takes us closer to the edge so that we can get a feeling of her personal despair.

ARROGANCE, LOSS, AND DEPRESSION: THE CASE OF MAYOR GIULIANI AND KING LEAR

Closely linked to sadness and depression are the feelings of loss that come from failure or rejection. In the year 2000, a front-page article in the New York Times reported on some apparent personality changes that members of the press were witnessing in Rudolph Giuliani, the mayor of New York City at the time. In my experience, people’s personalities don’t change very often and the Times piece intrigued me enough to start digging a little deeper.

During his eight years as mayor, Rudolph Giuliani was variously referred to in the media as an insensitive bully, a man seething with anger and self-righteousness as well as someone with a reservoir of warmth, charm, and compassion. Such contradictory assessments were often made by the same people as Giuliani changed over his term. One thing that the majority of New Yorkers agreed on was that he was an effective mayor. He helped rescue the city financially, reduced crime, and restored tourism. Because of his mayoral success, he had begun a campaign for the 2000 U.S. Senate seat against Hillary Clinton.

In late spring of 2000, Giuliani’s life turned upside down within a two-week period: He was diagnosed with prostate cancer, withdrew from the senate race against Hillary Clinton, separated from his wife on national television (before telling his wife), and, a few days later, acknowledged his “special friendship” with Judith Nathan, whom he later married. By mid-May, he was living in a friend’s apartment while undergoing treatment for his cancer. By early June, friends, acquaintances, old enemies, and members of the press all noticed that Giuliani seemed more genuine, humble, and warm.

One of the most reliable predictors of depression is experiencing traumatic life events. In fact, the more traumatic upheavals people experience at any given time, the higher the probability of depression and illness. Could we see changes in Giuliani’s personality by looking at his language? Fortunately, the New York City mayor had frequent press conferences that we were able to analyze. Specifically, we wanted to know if his function words had changed over the course of his emotional upheavals compared to earlier in his term.

Compared to his first years as mayor, Giuliani demonstrated a dramatic increase in his use of I-words, a drop in big words, and an increase in his use of both positive and negative emotion words. He also shifted away from first-person plural pronouns, or we-words. Recall from earlier chapters, we-words are used frequently when people are arrogant, emotionally distant, and high in status. Males especially use we in a distancing or royal form: “We need to analyze that data” or “We aren’t going to put up with higher taxes.” In Giuliani’s case, his language suggested an interesting personality switch from cold and distanced to someone who was more warm and immediate.

When the first phase of the Giuliani project was complete, there was something about the results that seemed eerily familiar. And then it hit me: Shakespeare’s King Lear. In the play, King Lear starts off as an arrogant ruler who demands that his daughters publicly declare their love and admiration for him. His favorite daughter, Cordelia, refuses and ultimately leaves England and marries the king of France. Wars, fights, recriminations, and misery follow. (Note: this is the CliffsNotes version of the play.) In the final act, the mortally wounded King Lear confronts the corpse of his beloved daughter. He is transformed. After facing the trauma of his losses, his personality exudes warmth and humanity. See the connection with Giuliani? Read Shakespeare’s first and last speeches by Lear:

Act 1, Scene 1. King Lear speaks:

Know we have divided in three our kingdom; and it is our fast intent to shake all cares and business from our age, conferring them on younger strengths while we unburdened crawl toward death. Our son of Cornwall, and you, our no less loving son of Albany, we have this hour a constant will to publish our daughters’ several dowers, that future strife may be prevented now … Tell me, my daughters (since now we will divest us both of rule, interest of territory, cares of state), which of you shall we say does love us most? That we our largest bounty may extend where nature does with merit challenge.

Act 5, Scene 3. King Lear’s final lines:

Oh, you are men of stone. Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so that heaven’s vault should crack. She’s gone forever! I know when one is dead, and when one lives. She is dead as earth … A plague upon you, murderers, traitors all! I might have saved her; now she’s gone for ever! Cordelia! Stay a little. What is it that you say? Her voice was ever soft, gentle, and low … I have seen the day, with my good biting falchion. I would have made them skip. I am old now, and these same crosses spoil me. Who are you? My eyes are not of the best. I’ll tell you straight … Pray you undo this button. Thank you, sir. Do you see this? Look on her!

The analyses of these two speeches make for a fascinating parallel with the changes seen with Mayor Giuliani. In fact, the relative usage of pronouns and big words by Giuliani and Lear in their early arrogant periods compared with their post-trauma warm-and-honest periods is almost disconcerting. During the arrogant periods, both Lear and Giuliani used low rates of I-words and emotion words and, at the same time, high rates of we-words and big words. These patterns were reversed for both when faced with life-changing (and, in Lear’s case, life-ending) personal upheavals. Life imitates art and science is here to record it.

The Giuliani story unfolded in another interesting and important way after his personal crisis in 2000. A little over a year after his personal crises, Giuliani was serving his last months as mayor when the September 11 attacks brought down the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center, killing almost three thousand people. By all accounts, Giuliani emerged as a powerful and compassionate leader of New York and the United States.

Giuliani’s news conferences in the first weeks after the attacks were marked by genuine warmth and grace. Analysis of his language revealed a new pattern of word use. His use of I-words was moderately high (3 percent) as was his use of we-words (3.2 percent). His use of we-words, however, stood out in another way. Early in his administration, his we-word usage was often vague, referring to society at large. After the attacks, his we-words were much more targeted and personal, referring to the residents of New York City or particular groups in government.

THE LANGUAGE OF KING LEAR AND MAYOR GIULIANI: PERCENTAGES OF TOTAL WORDS |

||||

LEAR |

GIULIANI |

LEAR LAST |

GIULIANI |

|

I, me, my |

2.0 |

2.1 |

7.4 |

7.0 |

We, us, our |

12.0 |

2.5 |

0 |

1.0 |

Big words |

18.9 |

17.0 |

7.4 |

12.5 |

Note: The Shakespeare analyses are of the first and last speeches by King Lear; the Giuliani data are based on press conferences during the first four years of Giuliani’s administration and during the two months immediately following his announcement of his prostate cancer. Numbers are percentage of total words within speeches (for Lear) and within press conferences (for Giuliani).

The Giuliani project complements the suicidal poet results in demonstrating the links between emotional states and function words, particularly pronouns. Emotions both reflect and affect our social connections with others. Pronouns, by their very nature, track the relationships between speakers and those they are communicating with. Pronouns and other stealth function words serve as subtle emotion detectors that most of us never consciously appreciate.

HOW TRAUMAS UNFOLD: USING WORDS AS WINDOWS

There are at least two ways people deal with emotional pain—acknowledging it and avoiding it. The suicidal poets, the imaginary king, and the real mayor all acknowledged their pain and loss. Socially, their elevated I-word usage made them appear more introspective and vulnerable. Looking inwardly can intensify the pain, motivate the person to understand and come to terms with it, and alert others about his or her emotional distress.

Another common strategy people adopt in dealing with pain is to avoid it or, in some way, distance themselves from it. Recall Denise Levertov’s poem “The Ache of Marriage,” where she analyzed the experience in a less personal, more distant way. Other avoidance strategies include trying to put the unwanted emotional experience out of mind altogether. In fact, distancing oneself from pain can be a very effective way to regulate emotions, especially in the short run. If I receive bad news about the death of my dog just prior to a business meeting, it behooves me to ignore my feelings and to continue the meeting as though nothing has happened even though part of me wants to collapse onto the floor and wail.

There appears to be an art form to avoiding emotional pain in the short run. In a series of brilliant laboratory studies, Dan Wegner and his colleagues have shown that people can’t just stop thinking about an emotional event. Rather, they need to start paying attention to something else. If something terrible happens before that meeting, Wegner would advise you to think about the meeting itself and not say to yourself “Don’t think about the dog, don’t think about the dog.”

When do people naturally use avoidance versus acknowledgment strategies in dealing with traumatic experiences? Only recently have scientists been able to track the ways people react to traumas as they unfold. Through a mix of technological innovations, it is becoming clear that most people tend to adopt both avoidance and acknowledgment strategies in the short run when dealing with upheavals.

THE SHOCK OF A TRAUMA IN THE FIRST HOURS

A few years ago my family and I were staying at the house of my friend Hector over the holidays. He asked me to listen to his voice messages and to contact him if there was an emergency. Several days into our stay, he received a message from a male who spoke in a quiet and flat tone:

Hector, it’s Nolan. Just calling to say that Marguerite died last night. She took a turn for the worse a couple of days ago. Thanks for calling last week. Really appreciate it. There will be a memorial service on Monday. Will try to call you later. Stay in touch. Take care. Bye.

I didn’t know Nolan or Marguerite nor did I know their relationship. But it was obvious that Nolan was completely crushed. As I listened to the message again, I tried to figure out why I knew that he was so devastated. He never said he was sad or in pain. He didn’t cry and his voice didn’t waver. The starkness of his language, however, was something I was not used to.

As a connoisseur of pronouns, I was struck that Nolan never used I, me, or my in his message. In fact, in the years since hearing Nolan’s voice message, I have heard at least three others where friends called to tell me about the death of someone close. And, like Nolan, they rarely used the word I.

More recently, I cataloged the first lines of blog posts from people who wrote about the death of a parent, spouse, or sibling that had occurred within the same day of their posting. Comparing their language with another post they made just prior to the death, the same pattern emerged. In the peak hours of suffering, most people used relatively few I-words and a low rate of negative emotion words. Their language was relatively simple, using smaller words, shorter sentences, and fewer cognitive words.

Immediately after a traumatic loss, people are often disoriented, numb, and in excruciating pain. As a way to reduce the pain, they regulate their attention away from their bodies. Intense grief causes people to pay less attention to themselves and their emotions. Instead, they focus more on the person who has died, their family, and the details of the death.

TRACKING THE EMOTIONS OF A COUNTRY: BLOGS OF SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

It makes sense that people psychologically distance themselves from a personal trauma in the minutes or hours after hearing emotionally overwhelming news. Does this happen on a broader scale when large groups of people face a traumatic experience? In the United States, when people heard the news of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln or John F. Kennedy, the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, or the September 11 attacks, they recalled where they were and what they were doing for the rest of their lives. Do people emotionally distance themselves when learning of a culturally shared trauma in the same ways we have seen with intensely personal events?

Unlike earlier cultural upheavals, the 9/11 attacks occurred when a sizable group of people were starting to blog regularly. An undergraduate on my research team with considerable computer expertise, Michael Cohn, dropped by my office a couple of weeks after the attacks and proposed analyzing the text of thousands of blogs to track how people changed in their writing and thinking from before the attack to the weeks and months afterward.

Working with a popular blog site at the time, LiveJournal.com, Michael, Matthias Mehl, and I saved the postings of over a thousand people who blogged at least three or four times per week in the two months before and after 9/11. We selected blogs from people who lived in the United States and who represented a wide range of ages. By all accounts, the bloggers were regular people who simply liked to blog about a broad array of topics. Analyses of over seventy thousand blog entries revealed startling changes in pronoun and emotion word use from before to during to after the attacks.

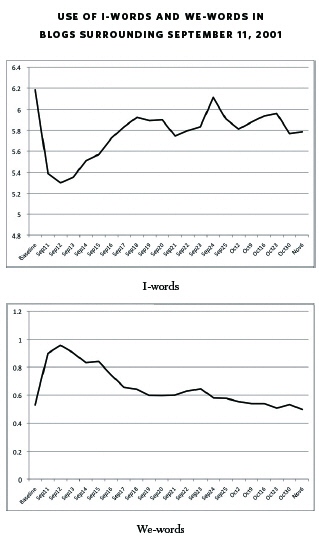

Consistent with the telephone messages and blog entries soon after a death, online bloggers immediately dropped in their use of I-words as soon as they learned of the September 11 attacks. In the top graph on the next page, you can see that use of I-words dropped substantially from the baseline level of 6.2 percent. From a statistical perspective, this was a jaw-dropping, breathtaking change.

Hold on to your seats; there’s more. Just as I-words dropped, use of first-person plural we-words jumped at an even higher rate. As you can see on the bottom graph, use of we-words almost doubled from before to after the attacks. Recall from earlier chapters that there are different types of we-words. The types of we-words people used were a mix of we meaning Americans and we referring to family.

Here are two examples.

A twenty-five-year-old female, whose previous blog entries described her attraction to another man and the awkwardness of running into an old boyfriend, was deeply shaken by 9/11:

Note: Graphs reflect percentage of I-words (top) and we-words (bottom) within daily blog entries of 1,084 bloggers in the two months surrounding September 11, 2001.

I watched the buildings collapse, I cried as the WTC [World Trade Center] came tumbling down … My sadness was replaced with anger … and fear. The idea that our home is no longer safe. I think we are as angry for loss of safety … as we are for the lives that were lost.

This man’s earlier blogs were generally devoted to philosophical and cultural topics. The day before the attacks, he wrote at length about Ayn Rand and libertarianism. The next day he became the epitome of social responsibility:

What can we do to help? Blood banks are probably VERY crowded right now, and may be for several days. Don’t let that stop you. YOU are needed. YOU can help.

Approximately 92 percent of the blog entries mentioned the attacks in the first twenty-four hours after the collapse of the buildings. In a powerful way, it forced people to embrace others in their family, community, and nation.

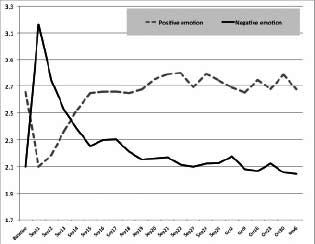

Analysis of people’s use of emotion words in the blogs bolstered the pronoun findings. After relatively brief drops in positive emotions and increases in negative emotions, people’s use of emotions returned to normal. And, in fact, they tended to express more positive emotions than they did before the attacks occurred. To capture these effects, our computer counted the percentage of words that reflected positive emotion (e.g., love, happy, gift) as well as negative emotion words (hate, cry, worry). As you can see in the next figure, during the two months prior to the attacks, people generally used far more positive than negative emotion words. People are basically quite positive in the ways they communicate with each other.

Across the seventy thousand blog entries, the terrorist attacks resulted in an immediate surge in the expression of negative emotions that lasted about two days; then negative emotions returned to pre-attack levels in about eleven days. At the same time, the drop in positive emotion word use showed an even more striking pattern. After a precipitous drop on 9/11, the use of positive emotion words returned to pre-attack levels within four days. By ten days after the attacks, people’s positive emotions were higher than they were before the attacks.

Note: Lines reflect the use of positive and negative emotion word usage of 1,084 bloggers. Baseline is the average of two months of blog posts prior to September 11. Data points through September 25 are by day, and thereafter by week through November 6.

One final important finding emerged from the 9/11 project. In the five or six days after the attacks, the bloggers used cognitive words at much higher rates than before 9/11. Recall that cognitive words include words that reflect causal thinking (e.g., because, cause, effect) and self-reflection (e.g., understand, realize, meaning). The cognitive words typically indicate people’s trying to understand what is happening in their lives.

An increase in the use of cognitive words immediately after an unexpected event makes sense—we all want to know what happened and why. However, starting about a week after the 9/11 attacks, the bloggers’ use of cognitive words dropped to unprecedented lows for the next two months. In fact, markers of thinking were far below the levels that existed before the 9/11 attacks.

Consider the implications of all these effects. The analysis of the thousand bloggers paints a picture of how normal, everyday people think following a large emotional upheaval. Note that within a few days of the 9/11 attacks most of the bloggers returned to writing about their usual topics—shopping plans, boyfriends, pornography, pets, the usual. Across all topics, however, the same patterns were emerging. A summary of the bloggers’ language suggests:

• Shared traumas bring people together. They pay more attention to others and refer to themselves as part of a shared identity—as can be seen in increased use of the warm you-and-I form of we.

• Shared traumas deflect attention away from the self. Even though people may feel sad, they are not depressed. Recall that people who are truly depressed show higher I-word usage, not lower I-word usage.

• Shared traumas, in many ways, are positive experiences. For at least two months after the 9/11 attacks, people expressed more positive emotions and were more socially connected than they had been in the months before the attacks.

• Shared traumas make people stupider. OK, maybe not stupider but certainly less analytic. Within a week of the attack, people wrote in simpler ways, suggesting that they weren’t thinking deeply about their writing topics. In fact, they seemed more passive and accepting of new information.

• People’s reactions to traumatic experiences change over time. The ways people think, feel, and pay attention to their worlds change drastically in the hours, days, and weeks after an emotional upheaval.

BEYOND 9/11: MAN-MADE AND NATURAL DISASTERS

Evolutionary psychologists look at the 9/11 findings and note how they make evolutionary sense. If we are in a small group on the savannah and are attacked by another group, it is critical that we band together, focus outwardly, and prepare for possible future attacks. These are adaptive reactions that can help to increase the survival of the individuals and the group itself.

Do the same language patterns exist for shared emotional upheavals that do not directly threaten the group? The answer appears to be yes. Over the course of my career, I have studied the social and psychological effects of a number of large-scale upheavals, including the Mount St. Helens volcano eruption in Washington state in 1980, the Loma Prieta earthquake in the San Francisco bay area in 1989, the first Persian Gulf War in 1991, the death of Princess Diana in 1997, and the tragic death of twelve students at Texas A&M university during the building of their traditional bonfire in 1999.

Across all of the studies, similar themes emerge that bolster the 9/11 findings. The most striking phenomenon is that all kinds of upheavals bring people together. People become more selfless, more concerned with others, and actively seek out relationships with others. Interviewing people in Yakima, Washington, several weeks after Mount St. Helens had dumped almost four inches of sandlike ash on their community, most of the residents reported that it had been a frightening experience but that, despite their losses, they were glad it happened in their lifetimes. Most reported meeting and talking with neighbors they never knew.

The university community of Texas A&M was shaken by the deaths of twelve students caused by the collapse of their symbolic bonfire. Again, in interviews, online blogs, and newspaper accounts, the language of the community was selfless and warm. In fact, the social bonds of the university ended up being tighter than anyone had seen before. In tracking the physical health of the student body over the following year, we found that the students went to the student health center for illness 40 percent less compared to the year before the bonfire disaster. No such effects occurred at A&M’s neighbor, the University of Texas at Austin.

It’s almost heretical to admit but terrible experiences can bring out the best in us. By their very nature, traumas can destroy some lives and enrich others.

USING LANGUAGE ANALYSES TO GUIDE MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH OF AN EMOTIONAL UPHEAVAL

One of the best-kept secrets in the mental health world is that most people actually cope quite well when faced with truly horrible life events. Most of us think just the opposite. When researchers ask us how we might react if something horrible happened to us, they find that we tend to believe that personal traumas would psychologically cripple us. In fact, the majority of people who have experienced torture or rape or who have survived terrible car or plane crashes or other unimaginable events don’t evidence symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or major depression.

Humans, it seems, are remarkably adaptable. They also naturally know what to do when a trauma strikes. Keep in mind that the overwhelming number of bloggers that have been studied are in good psychological health—meaning that whatever they do is probably not a bad idea. One finding is clear and a little counterintuitive: It can be healthy to distract yourself from your pain. Paying bills, helping others, playing video games, or cleaning your house are all time-honored methods of coping with profoundly disturbing news. If you want to talk with people about the event, talk to them. If you want to be by yourself, be by yourself. There is no convincing evidence that any single coping method works well for all people.

If you are a mental health professional, this advice is very unsatisfying. If a disaster hits and you see people in great distress on television, your natural inclination is to run out and help. Again, all the evidence indicates that the best way you can help is to make sure people have their basic needs fulfilled, that someone can answer their questions, and that someone will listen to them. People do not need in-depth psychotherapy right after a disaster hits. Far from it.

In the 1990s, a well-meaning psychological intervention became popular that encouraged traumatized people to disclose their deepest emotions about their trauma within the first seventy-two hours after it occurred. The movement, then called Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), sounded quite reasonable and was adopted by emergency workers, large corporations, and wings of government around the globe. Despite the good intentions behind the program, there were some serious problems with it. After a large number of studies, it is now generally agreed that CISD probably causes more harm than good. In looking at the ways people use language online in the first hours after a trauma, deep emotional processing immediately after an emotional event is not what healthy people do.

Most people need social support after an upheaval. One of the most striking phenomena my students and I have seen in studying blogs is the degree to which people seek and receive support from others. When people are distressed after an upheaval, they merely mention their emotional state and a flood of well-wishing comments from friends and strangers follows.

As part of her doctoral dissertation dealing with the language of diet blogs, Cindy Chung tracked what factors led to successful weight loss across several hundred dieters in a diet blog community over several months. Many of the bloggers focused on the details of losing weight but the majority also wrote about their relationships, life experiences, and emotional issues. Many dieting experts would recommend that the best way to lose weight is to obsessively list the foods you eat, the number of calories you have taken in, and the amount of exercise you have done on a daily basis. Not true according to Chung’s research. Instead, she found the very best predictor of successful weight loss was being involved in the online social network. That is, the more comments or posts a person sent out and received, the more successful they were at losing weight. In addition, bloggers writing about personal and emotional issues were far more successful in losing weight than those who wrote only about their foods and diets.

THE LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF TRAUMAS: HOW WORDS CAN HEAL

As the blog data suggest, most people initially cope with a traumatic experience by seeking out friends and family. The ways people talk or write about the upheavals vary considerably and may not involve any deep emotional discussions.

If people could always respond to emotional events the ways they wanted or needed, there would probably be less of a demand for therapists and physicians. Traumas, even highly personal traumas, are deeply social. If I have been raped or mugged, I may be hesitant to tell others because of the humiliation or the fear that others will treat me differently. Consequently, my natural reactions to talk openly about the experience will be stifled. Similarly, I may need to appear strong and happy to my family to avoid their becoming anxious or depressed.

THE DANGER OF SECRETS

Events that are shameful, embarrassing, or could damage one’s reputation are often kept secret for years. I discovered this early in my career when I included a questionnaire item that asked people if they had experienced a traumatic sexual experience prior to the age of seventeen. In surveys of thousands of adults, approximately 22 percent of women and 11 percent of men said they had. Particularly striking was that this same group had terrible health compared to people who had not had traumatic experiences. Later studies showed that the problem was that the sexual traumas were almost always secret traumas. Any type of major upheaval that people kept secret from others tended to compromise their physical and mental health.

Big emotional secrets are toxic for several reasons. One of the first interviews I conducted that illustrated this was with a thirty-five-year old woman I’ll call Laura, who had been about twelve when her mother remarried. Starting a few months after the marriage, her new stepfather, Jock, would occasionally sneak into Laura’s bedroom in the middle of the night and fondle her. Terrified, she tried to get him to leave even though he would make light of the situation. This continued off and on until Laura was fifteen, when she left home to live with an aunt. As she described it:

I had always been close to my mother. The divorce had nearly killed her and she was so happy with Jock. If she had known what Jock was doing to me, it would have broken her heart. I wanted to tell her so much. Do you know what it is like to be in a family like that? I’d get up in the morning and Jock and my mother would come down together. He would smile and be friendly, like nothing had happened. I hated his guts but could never tell anyone why. Every morning, every evening, every time I saw that bastard, I felt sick to my stomach.

Looking back on it all, the very worst thing was that I couldn’t talk to my mother anymore. I had to keep a wall between us. If I wasn’t careful, the wall might crumble and I’d tell her everything. The same was true of my friends. I’d go out with my girlfriends and we would all giggle about boys and dating. Their giggles were real, mine weren’t. If they had known what was happening in my bedroom they would have died.

I have heard or read variations on this theme hundreds of times over the last twenty-five years. In Laura’s case, the fondling was horrible but the collateral effects were worse. All of her close relationships with family and friends were damaged, her physical health deteriorated, and she was not able to talk about the experience to anyone until several years later.

Not talking about a major emotional upheaval violates our natural ways of behaving. As we have seen, emotional events provoke conversations. If we witness a terrible accident, discover that our favorite sports team has won an important game, learn that our closest friend has just left her husband, we feel the need to talk about it. This urge to talk about unexpected and upsetting events is fundamentally human. It is found in all cultures that have been studied. People talk about emotional experiences to learn more about them. Talking, it seems, is one of the primary ways that we are able to understand complex experiences. Conversely, when people are not able to talk about emotional events, they tend to think—even obsess or ruminate—about them.

TRANSLATING SECRETS INTO WORDS: EXPRESSIVE WRITING

As described in the first chapter, the links between secrets and illness motivated me to turn this idea on its head. If we encouraged people to talk or write about upsetting experiences, would their health improve? The answer turned out to be yes. In our first experiment, college students took part in a writing study where they were initially told that they would be writing about assigned topics for fifteen minutes a day for four consecutive days. After agreeing to participate, half of the people were told that they would write about deeply traumatic or stressful experiences for the four days. The other half of the students were instructed to write about superficial topics, such as describing objects or events.

Overall, people who were asked to write about emotional topics exhibited better physical health than those who wrote about superficial topics. Those in the experimental condition who wrote about traumas went to the doctor at half the rate of people in the control condition in the six months after the experiment. Later studies found similar patterns. Writing about traumatic experiences improved people’s physical and mental health.

Other researchers soon found that expressive writing affected immune function and other biological processes associated with health and illness. Josh Smyth from Syracuse University and his colleagues published a powerful study with arthritis and asthma patients showing that writing influenced the course of the diseases. Other projects with people dealing with AIDS, cancer, heart disease, depression, cystic fibrosis, and a range of other physical and mental health problems benefited from expressive writing. Now, almost twenty-five years later, over two hundred scientific articles have been published pointing to the power of writing.

The early writing studies were the impetus to develop a text analysis method that could help us figure out why writing worked. Awakening people’s emotions about earlier upheavals forces them to think differently about them. Exploring emotional topics demands that people look inward (as we see by their increasing use of first-person singular I-words). It helps them to organize their thoughts and construct more meaningful explanations or stories of their lives (as seen in the increasing use of cognitive words). By tracking the ways people write about their traumas, we are witnessing how they are changing in their thinking.

Writing is not a panacea and its effects are limited. For example, there is no evidence that writing about an emotional upheaval immediately after it occurs is helpful. Although writing for a relatively brief time over a few days has generally worked, it is unclear that long-term diary writing is necessarily helpful. In fact, writing too much about a particular problem may be a form of rumination. My recommendation is if you are interested in expressive writing, try it out for a few days. If it is beneficial, great. If not, try something else.

TYING IT TOGETHER: EMOTIONS AND THINKING STYLES AS TWO SIDES OF THE SAME COIN

Remember Rex Ryan, the coach of the New York Jets football team who cried in front of his players after losing an important game? His emotional display reflected a change in the ways he was thinking about his team and its potential. Equally important, his tears were a powerful social signal to the players. You will recall that one of his players was quoted as being impressed by the coach’s commitment to the team and how his crying brought the team together. In a separate article, the same crying scenario signaled to a sportswriter that the New York Jets were falling apart.

Emotions are not just reactions to events. Different emotions can change the ways we think and influence how we respond to others. Emotions are intensely social in that they can draw us closer or push us farther apart. Emotions are also meaningful signals about other people’s motivations, goals, and intentions. The intimate connection between function words and emotional state naturally follows. Emotions make us think about the world differently and function words reflect this change in thinking.

The relationship between thoughts and feelings has been the subject of heated debate in philosophy and psychology for centuries. Both Aristotle and Plato argued that logic and emotions were fundamentally different processes. Descartes, writing in the seventeenth century, went farther by claiming that emotions undermined people’s abilities to think rationally. The early American psychologist William James also emphasized how emotions and passions frequently blinded people’s judgments. Sigmund Freud argued that fundamental emotional issues were the driving force of personality and behavior.

We are now beginning to think very differently about emotions and reason due, in part, to discoveries in the brain sciences. One of the most eloquent spokesmen for this new perspective is Antonio R. Damasio, a neuroscientist who has studied and written about the behaviors of people who suffer damage to the frontal lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe integrates information from primal emotional centers as well as regions associated with abstract reasoning and language. Many of the connections are so extensive that it makes no sense to make a sharp distinction between emotions and thoughts.

In his book Descartes’ Error, Damasio describes a procedure whereby people play a competitive card game. Healthy people with no brain damage are highly sensitive to rewards and punishments in making their decisions. Those with damage to their frontal lobes, however, seem to ignore the feelings they get from failure. He concludes that the emotions associated with losing help people to behave more rationally. Emotions inform thoughts.

That our feelings affect the ways we think about the world is the take-home message of this chapter. Our emotions influence our thinking, which is reflected in the ways we use function words. By extension, function words can give us a sense of how other people are thinking and feeling. They also serve as subtle public announcements alerting others to our own emotional states, our thinking patterns, and where we are paying attention.