CHAPTER 8

HOPEFULLY, YOU SHOULD now be convinced that function words reflect psychological states. Sadly, I’ve been keeping something from you: Word use rarely occurs in a vacuum. In most cases, when we use words we are talking or writing to another person, and at the same time, they are talking or writing to us. Most language use occurs among people in ongoing social relationships. What this means is that we can begin to use our word tools to investigate more than solitary individuals—we can begin to study human relationships.

Think what this means. The way that you and your lover, your parent, your boss, and your mortal enemy talk with each other provides important clues to the nature of your relationships. And not just the way you talk—the ways you and your friends e-mail, post updates on your respective Facebook pages or Twitter entries, inform us about your entire social network.

Social relationships have their own personality. One friend in my social network is someone I often talk to about personal and emotional topics, and when we meet, we always eat Mexican food; another friendship is characterized by our arguing and joking over beers. Even my e-mails to and from my two friends reflect the kinds of interactions we have during our periodic lunches. These different relationships have gone on for years and are both warm and fulfilling. If I were to analyze the language of these interactions, each would have its own fingerprint, its own conversational personality.

By inspecting the language of close relationships, a picture of the relationships themselves begins to emerge. Not only can we look at relationships over months or years but we can also track how two people are connecting with one another on a minute-by-minute level. For example, it is possible to tell how engaged two people are with one another by analyzing how similarly they talk with one another.

Consider this brief snippet of an IM interaction between two college students who are very much in love:

HER: I’m glad I can at least talk to you now, but I want to see you so badly. I hate being apart from you

HIM:  . I wish there was a heart-melting smiley … I love you

. I wish there was a heart-melting smiley … I love you

HER: Seriously though … I’ve always been the type of girl that I could go long periods of time and it wouldn’t be that I wouldn’t … think about you, it’s just that the distance wouldn’t get to me … but today, I felt like I was going crazy not seeing you! Like when I say I missed you like crazy … I mean CRAZY!!!!I love you too

HIM: I do love you … so much

Both members of the couple are closely attentive to each other and repeat many of the same words and phrases. Compare the words of intense love with words of intense, well, outrage. For several years, a daytime television talk show, The View, has commanded a large audience in the United States. The hosts are a group of smart and often opinionated well-known women with backgrounds in news, comedy, and politics. Over the years, occasional bitter disagreements have erupted that were both political and personal. On May 23, 2007, a long-simmering tension between the conservative co-host Elisabeth Hasselbeck and liberal Rosie O’Donnell erupted:

HASSELBECK: Because you are an adult and I’m certainly not going to be the person for you to explain your thoughts to. They’re your thoughts. Defend your own insinuations.

O’DONNELL: I defend my thoughts.

HASSELBECK: Defend your own thoughts.

O’DONNELL: Right, but every time I defend them, Elisabeth, it’s poor little Elisabeth that I’m picking on.

HASSELBECK: You know what? Poor little Elisabeth is not poor little Elisabeth.

O’DONNELL: That’s right. That’s why I’m not going to fight with you anymore because it’s absurd. So for three weeks you can say all the Republican crap you want.

HASSELBECK: It’s much easier to fight someone like Donald Trump, isn’t it? Because he’s obnoxious.

O’DONNELL: I’ve never fought him. He fought me. I told a fact about him—

…

HASSELBECK: I gave you an opportunity to clarify.

O’DONNELL: You didn’t give me anything. You don’t have to give me. I asked you a question.

HASSELBECK: I asked you a question.

O’DONNELL: And you wouldn’t even answer it.

HASSELBECK: You wouldn’t even answer your own question.

O’DONNELL: Oh, Elisabeth, I don’t want—You know what? You really don’t understand what I’m saying?

HASSELBECK: I understand what you’re saying.

Obviously, the tone of the interactions between the two lovers and the two adult television hosts is different. Unlike the lovers’ IMs, the women’s sparring resembles a schoolyard fight between two bullies. Despite the striking differences in the two interactions, it is intriguing to see how in both exchanges, the two people converge in their use of words. In both interactions, the two people are completely focused on each other and practically mimic what the other person has just said—one in a loving way, the other in sputtering rage.

Conversations are like dances. Two people effortlessly move in step with one another, each usually anticipating the other person’s next move. If one of the dancers moves in an unexpected direction, the other typically adapts and builds on the new approach. As with dancing, it is often difficult to tell who is leading and who is following in that the two people are constantly affecting each other. And once the dance begins, it is almost impossible for one person to singly dictate the couple’s movement.

In his poem “Among School Children,” William Butler Yeats asks, “How can we know the dancer from the dance?” In reading both transcripts, you get the feeling you can’t. You can almost hear the players adjust their speaking rate, tone, and volume. As they both become more emotional, their uses of words converge. Less obvious, however, is their parallel use of function words. That is, both the happy lovers and the angry talk show hosts tend to use pronouns, prepositions, articles, and other function words with each other at almost identical rates. In both interactions, the two people are on the same psychological page and it is reflected in their language.

VERBAL MIMICKING

Social scientists have long known that people in a face-to-face conversation tend to display similar nonverbal behaviors. When one person crosses his or her legs, the other person follows. When one makes a grand hand gesture, the other will likely do the same a bit later. This nonverbal mimicking was first thought to reflect how much the two people liked one another. In fact, it is a marker of engagement, or the degree to which the two are paying attention to each other. If you are in love or you are outraged with your conversational partner, the two of you will match each other’s nonverbal actions precisely.

The same is true for the words used in a conversation. If the two people are talking about the same topic then their words should be similar. After all, that’s what a conversation is. More interesting is that people also converge in the ways they talk—they tend to adopt the same levels of formality, emotionality, and cognitive complexity. In other words, people tend to use the same groups of function words at similar rates. Further, the more the two people are engaged with one another, the more closely their function words match.

The matching of function words is called language style matching, or LSM. Analyses of conversations find that LSM occurs within the first fifteen to thirty seconds of any interaction and is generally beyond conscious awareness. Several studies suggest that LSM is apparent in some unlikely places.

Imagine, for example, that you were required to answer a series of open-ended essay questions as part of a class assignment. Imagine also that each of the open-ended questions was written in a very different style, ranging from very formal to extremely informal in style. Would you notice the differences in the writing styles of the questions? More important, would you change the ways you answered the questions by adjusting your answers to match each question’s language style? Surprisingly, you would likely not notice the differences in writing styles but you would adjust the style of your answers.

Working with my colleague Sam Gosling and graduate student Molly Ireland, we set up an online class writing assignment for several five-hundred-person Introductory Psychology classes. Students were forewarned that they would need to answer four separate brief essay questions about aspects of a class writing assignment. We never told the students that the different questions would be written using different language styles. For example, one particular essay question was written either in a pompous, arrogant style or, in another version, the same question was written in a chatty “Valley girl” style. Here are two samples where students were asked to write about a particular theory that had been discussed in the textbook:

Pompous instructions: Although your professors gave this topic rather minimal attention, cognitive dissonance is a common psychological phenomenon with which the vast majority of uninformed laymen will be familiar … generating an example should be simple enough once one has become reasonably familiar with this concept.

Valley girl instructions: OK, we might not have talked about cognitive dissonance much. Which I think is totally crazy cause it’s like, everybody should be able to see that cognitive dissonance is majorly relevant. Like, it’s seriously happening ALL the time, you know??… So OK, it’s your turn. I mean, like really try to think of an example of cognitive dissonance and tell me everything about it.

At the end of both questions, everyone read the same instructions:

In the space below, give a real-life example of cognitive dissonance, explaining what led to it and how it was resolved. Support your example with evidence from your book.

So, like, you get the idea of the differences between the writing styles of the two questions. Interestingly, the students provided equally knowledgeable answers no matter what the writing style. The only difference was that students who received the pompous question answered in pompous ways and those who read the Valley girl instructions wrote in the same freestyle informal lingo. Because everyone responded to four different essay questions, each written in a different style, many students later reported not even noticing the writing styles at all.

It’s hard to look at those two essay questions and not notice the striking differences in the ways they are worded. Nevertheless, we all naturally adjust to the speaker (or exam writer) we are working with. In fact, Molly ran another experiment where she gave people two pages from previously published novels. She then asked her participants to pick up where the original author left off and to write another page of the novel. For half of her participants, she explicitly told them to try to match the author’s writing style. Molly found that everyone, even those who were not explicitly told to do any language matching, naturally matched the writers’ original styles. In fact, when people were directly told to match styles, they were slightly worse at style matching.

Language style matching is much more pervasive than you might think. You may have had the experience of watching a particularly riveting movie and then, afterward, talking like one of the characters you have just seen. Several people tell me that after reading a book with a distinctive writing style they find themselves writing and talking using that same style over the next few hours or even days. In fact, if I, like, started—you know—writing in a Valley girl style for like gobs of paragraphs, and, you know, if, uhhh, your phone rang and like you totally answered it? You would like majorly start talking like this.

I’ll stop now to preserve our respective senses of dignity.

LANGUAGE STYLE MATCHING AND THE BRAIN

If style matching is so pervasive, why does it occur? One explanation is that it is hardwired in our brains. In the 1980s, a team of Italian neuroscientists measured the activity of a group of brain cells in a macaque monkey that fired whenever the monkey grasped a particular object. Later, they discovered that the same group of cells fired when the monkey watched a person’s hand grasp the same object in the same way. Other studies suggested that there might be an entire group of brain cells that mirrors the actions of others. These groups of cells are collectively called mirror neurons or mirror neuron systems.

More recent studies have asked ballet dancers to watch videos of ballets while their brain activity was being scanned. The researchers found that mirror neuron systems became activated for ballet dancers while watching the ballet videos, whereas nondancers did not show the same activity. Most of us have had subjectively similar experiences. For example, if you have ever played tennis, you may have noticed that if you watch an intense match on television, you sometimes catch yourself subtly moving your arm in an attempt to hit the ball.

Particularly noteworthy is that most researchers report that mirror neurons are most dense in Broca’s area in the brain. You will recall from chapter 2 that Broca’s area is also the area implicated in the processing of function words. It’s not coincidental that the ability to use function words is closely linked to mimicking nonverbal behaviors and, according to recent findings, voice intonation and inflection. Indeed, many scholars now claim that the ability to mimic social behavior and its close links to Broca’s area explain the early development and evolution of language abilities.

The mirror neuron research is now relying on state-of-the-art brain imaging methods such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), where it is possible to see which parts of the brain are active during highly specific tasks. For example, a research team from Princeton University recently found that people who are particularly empathic show more brain activity in Broca’s area while watching short videos of people making emotional facial expressions than do people low in empathy. It should be emphasized that the mirror neuron research is still in its infancy with researchers often disagreeing about the best way to interpret the brain activity associated with empathy.

A question that emerges from the brain imaging research concerns the possible links between mirror neurons and language style matching. At this point, direct experiments have not been done. However, the studies we have conducted with style matching among students answering open-ended essay questions hint at some important parallels. Those students who evidenced the greatest style matching in response to the different question writing styles tended to be people who made the highest grades on the multiple choice exams. In other words, those students who were most committed to the class naturally paid closer attention to the essay questions. Paying closer attention resulted in greater correspondence between the function words in the questions and their responses.

We all have mirror neurons and have the basic ability to mimic and empathize with others. These abilities differ from person to person and also depend on whom we are talking with. We have all been in situations where we talked with someone who wasn’t interested in what we had to say. Admit it, we have also been in conversations where we weren’t interested in what the other person was saying. I might have a head full of mirror neurons but if I sit next to a stranger on a plane who spends the flight describing his joint pains, medication history, and phlegm observations, our respective function words will go in different directions.

HOW TO MEASURE LANGUAGE STYLE MATCHING

There are a number of ways that researchers have developed to tap the degree to which two people are using function words at comparable rates. Some of the techniques are mind-bogglingly complicated. Others are fairly simple. Here is a method that you can actually do with a calculator. The basic idea is that we want to find out the degree to which any two text samples are similar in their use of function words.

Although there are nine categories of function words (including personal pronouns, impersonal pronouns, prepositions, articles, conjunctions, negations, quantifiers, common adverbs, and auxiliary verbs), personal pronouns are the most common in everyday speech. Although our computer programs analyze all types of function words to calculate LSM, you can get a pretty good idea of people’s engagement with each other by just looking at their personal pronoun use.

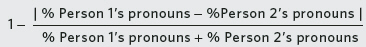

Look back at the nasty exchange between Rosie O’Donnell and Elisabeth Hasselbeck at the beginning of the chapter. To get a sense of how in synch the two women are, all we need to do is to calculate the rate of personal pronouns that each woman used, with the following formula:

In their brief exchange, Hasselbeck used 17 personal pronouns out of a total of 81 words and O’Donnell used 26 out of a total of 99 words. In other words, 21 percent of Hasselbeck’s and 26.2 percent of O’Donnell’s words were personal pronouns.

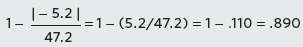

Recall that the vertical line, |, refers to absolute value. That is, when the personal pronouns from person 1 are subtracted from those of person 2, the result will always be positive. So in this case:

or

Voilà! The LSM score based on personal pronouns alone is a high .89. Interestingly, when all nine dimensions of function words are averaged together, the two women’s LSM score is even higher: an amazing 0.94—almost perfect synchrony. The LSM scale ranges from a perfect 1.00 if the two people are in perfect function word harmony and as low as 0 if they are completely out of synch. In reality, numbers below .60 reflect very low synchrony and those above .85 reflect high synchrony.

RIDING THE LSM ROLLER COASTER OF CONVERSATIONS

Mirror neurons help us to quickly synchronize our conversations with others. From a communication perspective, this makes good sense. Whether talking with an old friend, a business associate, a stranger on a plane, or a salesperson, we adapt our language style to set up a common social framework and to reduce friction. Style matching helps ensure that the people are similar in their emotional tone, formality, and openness, and understand their relative status with each other.

Further, our brains are highly attentive to changes in language style over the course of an interaction, constantly making corrections in the ways we use words. Style matching waxes and wanes over the course of a conversation. In most conversations, style matching usually starts out quite high and then gradually drops as the people continue to talk. The reason for this pattern is that at the beginning of the conversation it’s important to connect with the other person. Both people need to know how the other person is thinking and feeling. As the conversation rolls on, the speakers begin to get more comfortable and their attention starts to wander. There are times, however, that style matching will immediately increase. The best examples can be seen when unexpected shifts in the conversational topic or tone occur.

Imagine you are planning a surprise birthday party for a close friend. The day before the party, your friend mentions that she is thinking of going to a movie the next evening at the time you have scheduled the party. You must quickly come up with a lie that makes sure she will be around for the party. From her perspective, this is an innocuous conversation; from yours, it has become highly charged. If we could track the words between the two of you, what would happen to your style matching? Surprisingly, it will go up but not in the way you might think.

TALKING TO LIARS

The tone and direction of a conversation changes drastically as soon as one of the people starts to lie. Jeff Hancock, the Cornell researcher who studies the language of deception, has conducted some experiments that demonstrate this. In one project, he brought pairs of students into his lab and told them that they would have four online conversations on four different topics. In other words, their chatting would be from computers in different rooms so that they couldn’t actually see each other. So that both partners knew how the system worked, they were first asked to chat in a get-to-know-you kind of way for about five minutes. Once both were comfortable with the online chat systems, the experimenter gave both partners a list of the official conversational topics that they were to discuss for five minutes each. The sneaky part of the study was that one of the two partners received the topic list and, for two of the four topics, was instructed to blatantly lie about their views. Their partners never knew about this and so assumed that all of the conversations were, in fact, honest and straightforward.

We already know that when people lie, their language changes. You might have thought that style matching would drop during the deception topics. In fact, partners’ style matching increased during the deception topics. Yes, the liars’ language changed when they were deceptive but the innocent truth-tellers’ language changed as much or more.

Think what is happening in this situation. Once the study starts, the innocent partner has already had at least one honest conversation with the person and then, out of nowhere, the other person starts speaking differently. Our brains are highly attentive to change. In this situation, the innocent person is detecting that something is “off” or not making sense. Consequently, he or she starts paying closer attention, resulting in higher style matching. This is clearly not a conscious process because most innocent partners later report that they thought the deceptive conversations seemed normal.

There is something about this study that has always puzzled me. Think back to the dilemma of the surprise birthday party. If I have to lie to my friend to convince her to stay home the next evening, I have to think fast and come up with a reasonable story. Lying is hard work and during my lie, I won’t be paying much attention to my friend. Instead, she will be paying attention to me. Hancock’s findings indicate that my friend’s language use will accommodate to my deceptive way of speaking.

There is an interesting paradox about LSM. In the case of deceptiveness, one of the speakers—the person who is lying—is actually paying less attention to the other person. Intuitively, you would think that this would result in lower levels of style matching. Apparently when we talk with liars we start paying more attention in an attempt to decode their odd language change. In the case of deception, as one person becomes less attentive, the other becomes more attentive. Surprisingly, this occurs far more frequently than you might think.

TALKING WITH DISTRACTED MULTITASKERS

Recent studies indicate that multitasking is both quite common and surprisingly ineffective. When people multitask, they are attempting to do several things at once with the net effect that the quality of their work across all tasks is diminished. We have all had the experience of talking with someone who, at the same time, was reading a text message, watching something on television, or pondering a deep existential question. The deception research hints that conversations with multitaskers would result in high language style matching; common sense would argue just the opposite.

Common sense fails again. Yla Tausczik, a graduate student in my lab with extensive background in studying online social media, set up a simple experiment to test this idea. She had pairs of strangers initiate get-to-know-you conversations on separate lab computers as part of a psychology experiment. The computer displays were programmed to have random numbers continuously float across the top of the screens. For half of the conversations, the people were told to just ignore the floating numbers. In the other half of the conversations, one of the partners was told to count the number of times that the number 7 appeared. The people they were talking with, however, were told to ignore the numbers and didn’t know that that their partner was multitasking by keeping track of the floating numbers. In other words, in half of the conversations, one of the two people was distracted during the entire conversation.

Much like the deception study, the distracted pairs actually showed slightly higher style matching than the non-distracted pair. Even odder, they tended to report liking each other more. In terms of actual word use, the distracted students were less negative, less complex, and more personal than non-distracted writers.

There have been very few times in my career that I didn’t believe my own results. It just didn’t make sense to me that style matching increases when talking to a multitasker. So I took things into my own hands and called two former students and asked if they would mind participating in a language project. The deal would be that we would have an informal talk on the phone that would be recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. The talk would actually be made up of three five-minute segments, and after each segment, they would complete a brief questionnaire. Both agreed to the rules. What they didn’t know was that on one of the three segments, I would be sitting in my office madly doing arithmetic problems as fast as I could.

The phone calls started and we talked about work, our lives, our mutual friends, and other issues of the day. During the period I was working on the arithmetic problems, I recall thinking, “Wow, I’m really good at this. I’m as socially adept when I’m busy as when I’m not.” Later, when I transcribed the conversations, I was startled to see how differently I spoke while engaged in the arithmetic problems. I stuttered and repeated myself. I deflected any complicated questions and tried to get the other person to talk more. Similar to the participants in Yla’s experiment, I tended to laugh more and used more positive language in general.

Both of my students rated the distraction phases of the conversation as enjoyable as the other parts. In fact, the LSM measures indicated that we matched in our language use during the distraction period at rates as high or higher than during the nondistraction periods. What happened, however, is that both students started speaking to me in the ways I was speaking to them. As I psychologically distanced myself from the conversation, my conversational partners did the same. What intrigues me is that none of us were consciously aware of it. In fact, after the phone calls, I discussed the conversations with both students, asking their perceptions. One said that she was vaguely aware that I was slightly more distracted during the arithmetic problems but said, “You often are distracted in phone calls.” Oooh.

Two people who respect and like one another learn how to dance with each other across conversational topics. They are both invested in paying attention to one another, even during periods of distraction or disagreement. What makes the conversational dance dynamic is that as one person’s attention wanders, the other person attempts to adjust to it. An unspoken rule in this dance, however, is that both people are ultimately committed to it. If one or both members of the conversation simply doesn’t care about the other person, the dance is at risk of falling apart.

CREATING A LANGUAGE LOVE DETECTOR

Wouldn’t it be nice if there existed a device that could alert people if they were compatible? You could take it on dates with you, and at the end of the evening, the two of you would read the love detector’s “date compatibility score” on the front of the meter and decide if you should meet again tomorrow or never see each other again.

Good news. We may have a prototype for your startup company. It’s not a device, really. Instead, it just requires that you use a digital recorder to transcribe your interaction and then analyze the words to assess LSM. Oh, and for it to work, you should probably plan on having at least ten dates that are virtually identical in format. Hmmm. Perhaps a bit like speed-dating.

THE DATING DANCE

Indeed, Molly Ireland, several other colleagues, and I have found that the LSM between couples on a brief four-minute date predicts if they want to meet again. As you may know, in a typical speed-dating session, you meet and talk with eight to twelve different “dates” for a few minutes each. At the end of each date, each person rates the other person before moving to the next date. Usually the following day, the daters contact the speed-dating organizers and tell them which of the ten people they would be interested in meeting in a more relaxed setting. Most people report that the conversations range from superficial to passionate to exhausting. Sometimes people meet the loves of their lives; most times they don’t.

Lonely hearts may not always like speed-dating but researchers love it. In a recent project, about eighty daters gave permission for us to record their four-minute conversations so that our research team could analyze their word use. Does LSM in the brief interaction predict whether the couple gets together in the future? Yes, to some degree. Those in speed dates characterized by above-average LSM were almost twice as likely to want future contact as those with below-average LSM.

More interesting, however, is that we could predict which couples would get together afterward better than the individuals themselves. Immediately after each brief date, participants completed a short questionnaire about the desirability of the person they just met. The individual ratings of desirability were, of course, related to their eventually meeting, but LSM was more strongly related. Why? Whether or not two people eventually meet up is dependent on both parties. A guy might find a woman attractive but she might find him repulsive. The two must tango together. And LSM is capturing the dance—whereas the questionnaire is just assessing the dancers separately.

PREDICTING YOUNG LOVE

Let’s assume that a relationship advances beyond the four-minute speed-date and the young couple starts to date seriously. Would style matching between the two of them predict the long-term prospects of their relationship? Preliminary findings suggest yes.

Most people in passionate relationships are highly attentive to their partners. They detect subtle shifts in the other person’s moods and behaviors. Linguistically, their levels of style matching are quite high. After a few weeks or months together, some couples begin to realize that their relationship may have a limited shelf life. As their attention to their partner wanes, their degree of language style matching drops as well.

By tracking the language style matching of young dating couples, it is often possible to predict which couples are most likely to survive. For example, my former graduate student Richard Slatcher and I worked on a project with young dating couples. Rich, who is now on the faculty at Wayne State University, wanted to see how the couples talked with each other using instant messaging, or IM. He recruited eighty-six couples who reported that they IMed with each other on a daily basis and who agreed to let us analyze several days of their messages. We then compared what happened to couples who had high LSM in their instant messages with each other and those who had low LSM.

Of the forty-three couples with the highest LSM scores, 77 percent were still dating three months later, compared with only 52 percent of the couples with low scores. In other words, those couples who naturally synchronized their function words with each other were more likely to maintain their relationship over time.

Reading the IMs of the various couples painted a clearer picture of how the relationships were succeeding or failing. The more successful high-LSM relationships revealed how both members of the couple were truly interested in each other. In addition, the overall tone of the IMs was positive and supportive. The relationships with lower LSM scores, which were more destined to fail, often revealed striking patterns of detachment between the two people. For example, the following couple had low LSM scores although they claimed that their relationship was passionate and satisfying. Nevertheless, their failure to connect with each other is obvious:

HIM: hey you! how ya doing?!

HER: fine you

HIM: great. me and jim are gonna go out on the town

HER: sweet

HIM: i have to find an oil painting of a cow for my mom’s birthday and i’m gonna get my hair cut hopefully. what are you up to?

HER: not much

HIM: bout to jump in the shower too. we had a sweet christmas party last night. i got pics. pretty funny. listening to christmas music, its great

HER: good

HIM: ha ha, not very chatty today

HER: eh well … guess not

HIM: so.… you have a good week? what are you doing this weekend?

HER: yeah it was okay. working

HIM: ah … oh well at least youll have $$$$$$$$! that’s good. Im gonna jump in the shower. you think of somehting to talk about! be back in 10 min if you’re still here. jim is waiting on me to get ready. bye bye

HER: then go!

HIM: miss ya! ha ha. fine bye

The male is chatty and, I would guess, falsely upbeat. His girlfriend is cool, detached, and unresponsive. His language is personal, with high rates of pronouns, and hers is noncommittal. By her relative silence, she is conveying her annoyance, which he avoids confronting.

Compare their interaction with another where the female is trying to emotionally engage her soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend. Over the previous two days of their occasional IMs, the female has tried to talk about their relationship and the male has constantly been busy with homework, exercising, even watching television. On the third day, she finally catches him when he might have some time to chat:

HER: are you there? are you gonna be able to talk for 5 minutes

HIM: yes. go

HER: what are you doing at the same time you’re chatting with me?

HIM: cleaning

HER: i feel too mad to say anything to you

HIM: fine

HER: did you not even feel one bit of bad when you read the card?

HIM: of course i did

HER: are you sure

HIM: hang on for 1 min please … Yes.

HER: or are you just saying … please hurry … hello?… what is the problem

HIM: alright … sorry

HER: what were you doing

HIM: my friends got here. Go

HER: but tell me what made you feel bad about the card

HIM: that you were being so nice. but i still dont feel that im wrong

HER: so why did you feel bad …

HIM: it did, but the fact that you told me not to expect it

HER: i don’t understand. the fact that i told you not to expect it made you feel bad?

HIM: look, i will call you @ nine. i cant speak like this

In this second case, the style matching numbers are also low. Although both use personal pronouns at similar levels, the computer analyses reveal that she is more concrete (using more articles) and more complex (e.g., conjunctions, prepositions) in her thinking than he is. She is also more personal and emotional, and focuses all of her attention on her boyfriend. He, on the other hand, is distracted and avoidant. Whenever she tries to get closer or to connect with him, he slips out of reach. This pattern of interaction was consistent over several days of instant messaging. Nevertheless, when both members of the couple completed questionnaires about their relationship, both rated their levels of intimacy and relationship satisfaction as very high (!). As is typical, the language style matching numbers did a far better job at predicting the couple’s later separation than their self-reports.

The LSM method allows us to make reasonable guesses about the success of relationships by tracking a few interactions between couples. Similar ideas have been tested with recently married couples. John Gottman and his colleagues at the University of Washington report that by listening to the ways a young couple fights during a laboratory exercise, he can predict the likely success of the marriage. Gottman brings the couples into his lab and has them discuss issues that they have conflicts about—usually topics dealing with money, sex, or household chores. If, during tense discussions, both members of the couple show respect, try to reduce tension, avoid accusations, and inject positive emotions, their marriage is more likely to last. On the other hand, if one or both spouses are dismissive of the other, actively avoid discussing an emotional topic, or use the task as a way to launch personal attacks on the other, the marriage is in trouble.

A happy marriage is more than the egalitarian sharing of pronouns and prepositions. When two people use function words in similar ways and at similar rates, they are seeing their worlds in parallel ways. Having a similar worldview, though, does not ensure marital bliss. Gottman’s work reminds us that the strongest relationships are also characterized by shared positive emotions. Similar findings emerged in our dating couples—those with the highest style matching scores and the highest rates of shared positive emotions were the couples most likely to stay together. Interestingly, shared positive emotions on their own do not predict the long-term happiness or potential for survival of a relationship. The members of the couple must be both positive in their outlooks and engaged with each other.

BUILDING AN LSM DETECTOR

Imagine having a portable LSM detector that could track the quality of all your conversations. Perhaps you could point the LSM detector at your e-mails, text messages, or IMs and get a sense of the quality of your connection with your correspondents. Or, if you have been married for many years, you could keep tabs on your relationship and help point out to your partner when he or she isn’t holding up their end of the conversation.

As discussed earlier, my research team and I have built a crude working version of an LSM detector. If you go to www.SecretLifeOfPronouns.com/synch, you can enter text that you have sent and received from a friend, lover, or enemy. With the click of a button, you will receive feedback about the degree to which the two of you are in synch in your use of function words. You can then compare your LSM numbers with average LSM scores generated by others who have used the website. Even better, you can try out the LSM detector several times, comparing your interactions with different people. This should give you a sense of your general skill at matching your language with others.

The bad news is that a real-world LSM detector would be of only limited value. Yes, it could tell us when relationships were in synch and out of synch but not what the synchrony meant. Recall that LSM tends to be elevated when both people are passionate about each other and when they truly hate one another. Synchrony also increases when one of the two people is lying to the other. So, if your LSM detector registers a high number, you and your conversational partner are paying close attention to each other.

Think of the LSM detector as a device that can evaluate the synchrony of the conversational dance. Good dancing requires each of the two people to anticipate the other’s next move and, in a sense, briefly inhabit their thoughts. The dancing may last only as long as the music is playing or could reflect the two people’s interest in each other and ability to synchronize their thoughts and actions for years.

USING LSM TO UNDERSTAND PAST RELATIONSHIPS

One advantage of using computerized language analysis is that we can explore relationships over history wherever some kind of written record exists. For example, if we have access to old letters, poems, or lyrics that two people shared, we can get a glimpse of their emotional connection with each other. Computerized text analysis can illuminate our understanding of marriages, friendships, or alliances in history. Molly Ireland, who has been immersed in the language style matching research, has tracked down several enlightening cases, two of which include the poems of poets from one well-known happy marriage and from one equally famous unhappy one. By analyzing their works, we get better insight into each pair’s relationship.

ELIZABETH BARRETT AND ROBERT BROWNING

The idea of measuring language style matching was initially developed to track word use in natural conversations. Conversations should be especially sensitive to the immediate back-and-forth of ideas and shared references implicated in the ways mirror neurons work. By standing back, it is possible to imagine that language style matching can occur on a much broader level. If I hear a rival politician make a speech on a given topic, I might write my own speech in reaction to it several days or weeks later that would linguistically match the original speech. If my spouse is an elegant writer of novels, her writing style could influence the way I write professional journal articles. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that two professional poets who read each other’s work might begin to use function words in similar ways—especially if the two people were passionately attracted to one another. A wonderful example is the case of the mid-nineteenth-century British poets Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning.

The two poets already had sterling reputations by the time they first corresponded when she was thirty-eight and he was thirty-two. Elizabeth, whose health had been poor since the age of fourteen, had never left home and continued to live with her despotic father while she wrote about emotions, love, and loss. Robert was a vibrant man-about-town whose work was more psychological and analytic. After Elizabeth published a poem that referenced one of his poems, Robert wrote her and professed his love for her work and, more directly, for her—even though the two had never met.

Over the next several months, they corresponded and he proposed marriage—something that she initially resisted by trying to pull away from him. After Robert relentlessly pursued Elizabeth, the two eventually eloped, moving to Italy, where they spent most of their lives together. By all accounts, the marriage was supremely happy, with both continuing to publish their work. The only dark time in their fifteen-year marriage came during the last two to three years, when Elizabeth’s health failed, resulting in her death at the age of fifty-five.

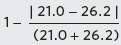

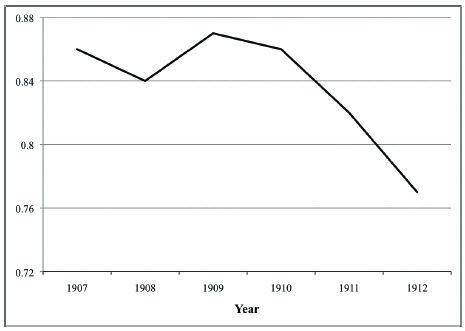

Over the course of their careers together, both Elizabeth and Robert were prolific, producing hundreds of poems. Even before they met, the two tended to use function words similarly. This may explain why the two were so attracted to one another long before they ever corresponded. As you can see in the graph, the LSM statistics indicate that their use of function words was quite similar before they met and for most of their marriage. During their one-and-a-half-year courtship, however, the poetry they wrote diverged. This was a period when Elizabeth struggled with the decision of breaking away from her father and, in her own mind, burdening Robert with her health problems.

As you ponder the figure, you might be curious to know who is responsible for the increasing and decreasing LSM over time. After all, LSM has been likened to a dance between two partners. Can we determine if one of the dancers is more responsible for the occasional faltering in the dance? In fact, we can. Closer inspection of both poets’ use of function words suggests that Robert was impressively steady in his writing style over the course of his career, whereas Elizabeth tended to alter the ways she used function words from one period to the next. For example, during most of their time together, Elizabeth’s use of function words tended to mirror Robert’s. However, during her difficult courtship year and as her health declined toward the end of her life, she tended to withdraw into her own world, writing less like Robert and less similarly to her own writing at other times of her life.

Language style matching (LSM) scores between the works of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning and of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. The higher the LSM score, the more similarly the two poets used function words.

SYLVIA PLATH AND TED HUGHES

Whereas the Brownings’ marriage is often idealized by modern writers, the relationship between Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes is not. Plath was born in Boston and met the British-born Hughes while she was on a Fulbright scholarship at Cambridge University. Both were considered rising young stars in the poetry world. Her writing was often emotional, confessional, and occasionally whimsical. His was more cerebral, often dealing with nature and myth. Four months after meeting at a party, they married—she was twenty-four; he was twenty-six.

During the first four years of their marriage, both experienced personal and professional success. Relative to Plath, Hughes’s writing came easily and he won several awards. About five years into the marriage, Plath’s health started to fail, including several bouts with influenza, an appendectomy, and a miscarriage. She accurately suspected Hughes of being unfaithful—often causing her to fly into violent fits of rage. Within a year, Hughes left Plath for another woman. Plath, who had a history of depression before her marriage, sank into a period of despondency. Even though she continued with her writing, she became increasingly isolated from her friends. Less than a year after her separation from Hughes, at the age of thirty, she committed suicide.

It is interesting to compare the language styles of Plath and Hughes over the course of their relationship—especially in comparison with the Brownings. As is apparent in the figure, Plath and Hughes had very different linguistic styles before they met. Hers was far more personal and immediate compared to his more objective, distanced style. During their relatively happy years, their styles converged to some degree before veering apart during the last three years of her life.

It is also interesting to see how the two couples differed in their language style overall. The much happier marriage of the Brownings was associated with greater language style matching across all phases of their lives compared with the Plath-Hughes relationship. It would be a mistake to conclude that language style matching was the cause of the Brownings’ success or the Plath-Hughes’s marital failure. Instead, the matching of function words between two people merely reflects the fact that the two people tend to think alike. It is even riskier to make bold statements about LSM and relationships by looking at people’s professional writing—especially when the two may be writing about very different topics aimed at different audiences.

BEYOND LOVE: ADMIRATION AND CONTEMPT BETWEEN FREUD AND JUNG

LSM analyses can tell us something about close intimate relationships. The instant messages between dating couples helped reveal which couples were most likely to succeed and fail. The more esoteric poetry analyses allowed us to infer the similarity in thinking between married poets, and, by extension, pointed to the high and low spots in their relationships.

But there is much more to LSM than romantic love and heartbreak. The analysis of function words can be applied to any kind of relationship between two people. As long as we have ongoing communications between people—letters, e-mails, Twitter interactions—we can use the LSM technology to assess the degree to which the correspondents are in synchrony with each other. After studying the language and marital relationships of poets, Molly Ireland and I turned our attention to relationships where a complete set of correspondence existed between two people. Depending on your perspective, this could be a relationship of love, a relationship of identification, an unresolved Oedipal complex, or just two friends.

The relationship between Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung lies at the heart of the history of psychology and psychiatry. By the late 1800s, Freud’s ideas about psychoanalysis were beginning to shake the foundations of Western thought. In a series of articles, he argued that people’s personalities and daily behaviors were guided by unconscious processes, many of which were highly sexual. He also promoted the idea that early childhood experiences shaped people’s mental health for the rest of their lives. Not only was Freud a creative thinker but he was also keenly aware of the mass appeal of his approach. One concern he harbored was that his work would be marginalized as reflecting a Jewish way of thinking.

Enter the young, ambitious, and Christian Swiss scholar Carl Jung. Fresh out of medical school, Jung became fascinated by the psychological underpinnings of thought disorders such as schizophrenia and the nature of the unconscious. In 1906, Jung mailed Freud a copy of his first book and Freud reciprocated with a recent article. After a handful of letters back and forth, they became close friends. Most scholars agree that they both liked each other immensely but, at the same time, were not blind to the professional advantages of a close relationship. In fact, after their first face-to-face meeting, Freud proclaimed Jung to be his “dear friend and heir” in a letter. By 1908, Jung was able to write to Freud, “let me enjoy your friendship not as one between equals but as that of father and son. This distance appears to me fitting and natural.”

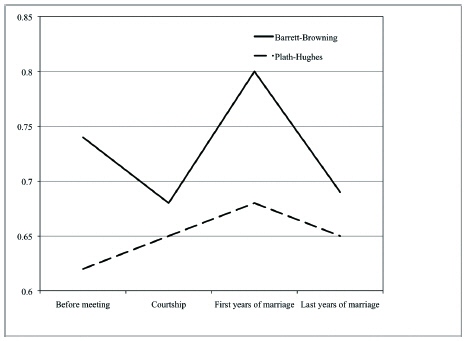

Language style matching scores in the correspondence between Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. The higher the number, the more closely the two men matched in their use of function words in their letters to each other.

Between 1906 and 1913, at least 337 letters were exchanged between the two men. During these years, Freud’s reputation skyrocketed. Jung was becoming a force of his own, and by 1911, tension between the two men started to build. Jung felt that Freud was emphasizing sexuality too much; Freud felt Jung was disloyal in not adhering to Freud’s own view. During the last months of their correspondence, Jung accused Freud of arrogance and being closed-minded. Freud responded that that they should “abandon … personal relations entirely.”

Analyzing the function words of the letters between Freud and Jung revealed a predictable pattern in terms of their language style matching. As you can see in the graph on the previous page, their style matching was exceptionally high in their first four years but then dropped precipitously after that. Closer analyses indicated that both men were equally invested in the relationship during the first years. However, toward the end, Freud was the one who disengaged and whose language changed more. Indeed, in one of his last letters to Jung, where he recommended they cease being friends, he added, “I shall lose nothing by it, for my only emotional tie with you has long been a thin thread—the lingering effect of past disappointments.”

UNDERSTANDING CLOSE RELATIONSHIPS WITH LSM

The conversational dance is played out in many ways. Who would have ever imagined that the ways people use pronouns, prepositions, and other function words could tell us so much about their relationships? With a little computer magic, we can use LSM as a barometer of the social links between two people. Or, more specifically, as a sign of the degree to which people are in synch with one another.

What does it actually mean to say that two people are in synch? At the most basic level, people who synchronize their use of function words are paying attention to each other. They may not like each other, they may not trust each other, but they are watching and listening to each other. Fortunately, people avoid spending much time with their enemies and opt to have their best talks with people they like. Most conversations with good friends or lovers are characterized by high LSM for the same reason—they are paying attention to each other.

It is difficult to fathom how two people can quickly adapt to each other’s language styles. As we’ve seen, it generally happens in a matter of seconds when talking with strangers. The two people immediately adjust to each other’s level of formality, concreteness, emotionality, and ways of thinking. Both people are constantly keeping track of which pronouns refer to which people and so keep a running tally in their heads of who the she, he, or it refers to. To keep the conversational ball rolling, both must adapt to shifting topics. In fact, if one of the two conversational partners is momentarily distracted or begins behaving oddly (as when lying), the other person must invest even more energy to maintain the interaction.

It is easy to understand why LSM is so high in both loving conversations and heated fights. Even in most boring discussions among people who do not care about each other, style matching is surprisingly high. Fortunately, the mirror neuron system constantly monitors what is being said and helps speakers convey what needs to be said with minimal effort. There are times, of course, when style matching fails terribly. Some individuals, for example, have great difficulty in language style matching. Certain disorders such as autism can interfere with people’s ability to mimic in general and to socially connect with others. Some researchers believe that autism-spectrum disorders, which include diagnoses such as Asperger’s syndrome, can impede interaction due to disruption in the function of the mirror neuron system.

In reality, we don’t always click with our conversational partners. In most cases, one or both of the people are simply not interested in either the conversation or the person they are talking with. Sometimes, one of the conversational partners simply doesn’t want to hear what the other person has to say. For example, I was recently at a gathering where I ended up sitting next to two people, let’s call them David and Ahmed. Prior to the meeting, Ahmed had learned that David had made some disparaging remarks about Ahmed’s wife. David, who was unaware of Ahmed’s knowledge, started a friendly story about running into a mutual friend. During that time, Ahmed avoided eye contact with David and, as soon as David’s story was finished, snatched the conversational ball and began talking with me about a recent book he’d read. Whenever David attempted to join the conversation, Ahmed either ignored him or changed topic yet again. Afterward, when I asked David about the conversation, he was unaware that Ahmed had ignored everything he said and felt that the interaction had been fine.

The Ahmed-David conversation is a reminder that people are not always aware of their failure to connect with others. Much like the study with the dating couples, people may completely fail to click with one another as measured by LSM numbers but think that their interactions are normal. Our research finds that both partners in these dysfunctional interactions often fail to appreciate the problems. Perhaps the thought that the other person is subtly rejecting them is too threatening to acknowledge. Perhaps the person who is dismissing the other can’t see the process either. If only the two people had the LSM Detector with them.