CHAPTER 9

Seeing Groups, Companies, and Communities Through Their Words

MANAGEMENT CONSULTANTS SOMETIMES distinguish among I-companies, we-companies, and they-companies. To get a rough idea of an organization’s climate, they ask employees to talk about their typical workday. If employees refer to “my office” or “my company,” the atmosphere of the workplace is usually fine. People working in these I-companies are reasonably happy but not particularly wedded to the company itself. However, if they refer to “our office” or “our company,” pay special attention. Those in we-companies have embraced their workplace as part of their own identities. This sense of we-ness may explain why they work harder, have lower employee turnover, and have a greater sense of fulfillment about their work lives. And be very concerned if an organization’s employees start calling it “the company” or, worse, “that company” and referring to their co-workers as “they.” They-companies can be nightmares because workers are proclaiming that their work identity has nothing to do with them. No wonder consultants report that they-companies have unhappy workers and high turnover.

How people talk about their company is only one way to tap the group dynamics of an organization. By listening to the words people use within any group, several features about the group’s inner workings can be unmasked. Through e-mails, web pages, transcripts of meetings, and other word clues, we can measure how much group members think alike. It is also possible to profile groups in terms of their cohesiveness, productivity, formality, shared history, and, in some cases, their honesty and intentions to change.

This chapter may not be of relevance to some people. If you do not have any family, co-workers, or friends, or know anyone in any organization, neighborhood, or community, you can skip this chapter and jump to the next. Everyone else should keep reading.

WE-WORDS AS IDENTITY MARKERS

I learned about I-, we-, and they-companies from a consultant I sat next to on a flight several years ago. About the same time, couples researchers were discovering some similar patterns. In a typical study, married couples would be invited into the lab and encouraged to talk either about their marriage or about a problem in their relationship. Sparks would sometimes fly—sometimes in good ways, sometimes not.

In general, the more a couple used we-words when being interviewed about their marriage, the better. When couples used the warm-and-fuzzy we that said “my spouse and I,” it signified a healthier relationship and, in some studies, predicted how long their marriage would last. Interestingly, the use of we-words only predicts a good relationship if the members of the couple are in the presence of an interviewer. Other studies where married couples were asked to wear a digital recorder for several days failed to find any patterns with we-words. The use of we-words around just one other person often means “you” or “everybody but you.” A couple’s use of we-words when talking to a third party predicts a satisfying relationship. However, we use for couples talking only to each other rarely predicts the quality of the relationship.

In the laboratory, when talking about marital disagreements, we-words indicated a good relationship whereas the use of you-words suggested problems. The use of you-words, such as you, your, and yourself, were most apparent in toxic conversations—usually where the two participants were accusing each other of various shortcomings.

We-words may even save your life. In one project, patients with heart failure were interviewed with their spouses. They were asked a series of questions, including “As you think back on how the two of you have coped with the heart condition, what do you think you have done best?” The more the spouses used we-words in their answers, the healthier the patients were six months later. The use of we-words by spouses indicated that they viewed their partner’s health problem as a shared problem that both were committed to fixing. When both members of the relationship were working together to cope with the illness, it reduced the physical and emotional stress on the patient.

We-words may even save your life if you are perfectly healthy. Analyses of commercial airline cockpit recordings have found that poor communication among the flight crew has contributed to over half of all airline crashes in the last century. In some cases, pilots established a toxic atmosphere that discouraged dissent. In other cases, one or more crew members were distracted and failed to listen to critical information from others. A recurring theme has been that the most effective crews are ones that are close-knit and feel they are part of a team. For example, Bryan Sexton and Robert Helmreich analyzed the language of flight crews during extended flight simulations. The more the crew used we-words, the fewer errors it made. In analyses of cockpit recordings of airline crashes, the ones characterized by clear human error are associated with much lower use of we-words compared to those caused by unavoidable mechanical errors.

Words such as we, us, and our can be powerful markers of identity. When people tell complete strangers about “our marriage,” “our business,” or “our community,” they are making a public statement about who they are and with whom they identify. “Our marriage,” for example, is a shared and joint entity. Similarly, “our business” and “our community” are groups that are a part of who we are.

THE EXPANDING WE: THE PERSON AND THE GROUP

The ways people think about themselves are constantly shifting. The shift between the use of I and we can be remarkably subtle and can occur almost instantaneously. In conversations, both speakers and listeners may not even consciously hear which pronouns are uttered. Nevertheless, the speakers’ use of we to refer to the listeners and themselves has psychological and social meaning.

You can get a sense of this shift in the following overheard conversation between two people talking about a real estate deal. Alex, about forty-five years old, is a lawyer who dabbles in real estate deals. Liz Ann, around forty years old, successfully got out of the stock market at its peak and has been involved in a number of investment projects.

ALEX: I’ve got a deal you might be interested in. It involves buying that property on Oak Street.

LIZ ANN: The last thing I need is another fight with the Darden Group.

ALEX: This isn’t with Darden. The original owners have approached me about selling it for tax purposes.

LIZ ANN: What are they asking? What would be my risk?

ALEX: Probably 350, with the usual side deals. We could offer 300.

LIZ ANN: I’m not sure this is the right time. But if we sidetracked Darden, I’d be happy.

Clearly the two people know each other and have worked together in the past. At the beginning of the brief conversation, the two are separate beings with their own agendas. They both use I-words each time they speak. In the next-to-last line, Alex tosses out “We could offer 300.” In Alex’s head, the two people have subtly morphed from two individuals to one group with common goals. The final line by Liz Ann suggests a possible acceptance of their shared identity. Even though Alex might not have consciously picked up Liz Ann’s use of we, his brain likely detected that she was leaning toward investing in the Oak Street property.

The use of we-words often signals that a person feels a part of the group. Experienced workers in sales jobs are often attentive to the ways people shift in their use of we-words. As suggested by the real estate conversation, when a customer starts tossing in we-words to refer to the salesperson-customer relationship, an important emotional bond has developed. If you are the one doing the selling, can you speed this relationship up by using we-words yourself? Probably not much. The premature use of we-words, much like the language of a politician, is often perceived as disingenuous and manipulative.

The sense of “groupness” is often illusory. Sometimes people feel that they are a solid part of the group they are in, and at other times, while around the exact same people, they feel detached, alienated, or alone. By tracking people’s use of we-words and I-words, it is possible to detect their perceptions of group identity. The same language analyses can also tell us about the groups themselves.

THE GROWING SENSE OF GROUPNESS: FROM ME TO US

The longer people talk with others, the more they use we-words and the less they use I-words. As we get to know others, we let down our guard and start to accept them. The pattern of increasing we-words and decreasing I-words emerges across a wide array of groups.

Speed-dating is the perfect place to start. Think back to the speed-dating project in the last chapter where strangers met for ten consecutive four-minute “dates” back-to-back. Even in these ridiculously short meetings, people’s use of we- and I-words changed quickly and predictably. Minute-by-minute in the brief speed-dating sessions, I-words for both people dropped and we-words increased.

The I-drop/we-jump effect can be seen far outside the dating context. In some studies, students visit a psychology laboratory and end up talking to a complete stranger for fifteen minutes in a get-to-know-you setting. In the first five minutes, both participants typically talk a little about their backgrounds, their majors, and where they live. Because both people are describing themselves, they tend to use I-words at relatively high rates. During the next five minutes, they talk less about themselves as they begin to establish common ground between them. By the final five minutes, their use of I-words drops between 10 and 50 percent compared to their starting levels. At the same time, their use of we-words increases anywhere from 20 to 200 percent. The patterns are even stronger in online get-to-know-you chats between two strangers.

The same shifts occur in larger groups. In a business school experiment with four-person groups, people worked on a complex group-decision task for thirty minutes. Same results: People in the groups decreased their I-word usage by 19 percent and increased their we-words by 39 percent from the first ten minutes to the last ten minutes.

More interesting are shifts in we- and I-words in real-world groups that last over hours, days, months, and even years. The airline cockpit project discussed earlier found similar patterns. The longer a crew is together, the more the group uses we-words.

And the I-drop/we-jump effect extends to bigger groups over much larger time frames. One project involved eighteen engineers, economists, and computer experts working on a complex online national defense project over almost two years. Another included around twenty professional therapists who met twice a year for three years as part of their professional training. Another project tracked the lyrics of the Beatles over their ten years of singing together. For all these groups, I-word usage dropped month by month, year by year, just as we-word use increased.

What does all this mean? The more time we spend with other people, the more our identity becomes fused with them. We may not necessarily like or trust them but as our history becomes intertwined, we see ourselves as part of the same group. An interesting corollary of this phenomenon happens as we age. By and large, the older we get, the more time we have spent with virtually everyone around us. One might even predict that older people would use fewer I-words and more we-words than when they were younger. And it’s true. In a study of language use among almost three thousand people, those over the age of seventy used 54 percent more we-words and 79 percent fewer I-words than adolescents.

BRINGING “US” TOGETHER: WHEN EVENTS CREATE GROUP IDENTITY

Gradually adopting the identity of a group is a natural process that we rarely notice. One minute in a conversation our opinions are sprinkled with I and the next with we. It just happens. There are other times, however, when the ways we identify with a group change quickly and dramatically.

The simplest examples can be seen with our allegiances to sports teams. One of the most clever social psychology experiments to demonstrate this was run in the mid-1970s by Robert Cialdini and his colleagues. Students who were attending universities with top-ranked football teams were called in the middle of football season as part of a survey purportedly dealing with campus issues. In the previous weeks, their home football teams had won a major game but also had lost another. After a few preliminary questions, the interviewer asked about one of the two pivotal games in the season, “Can you tell me the outcome of that game?”

If their team had won, they usually answered, “We won.” But if their team had failed to win the game, their answer was more likely “They lost.” Taking partial credit for your team’s winning is a form of basking in reflected glory. Basically, we want to be close to groups that are successful and distance ourselves from losers.

The sense of wanting to belong to a powerful group may have its roots in evolution. Most social animals seek the protection of a group when they are threatened. Even the appearance of an outsider can make people more aware of their own social network. In the same football project, Cialdini’s interviewers sometimes claimed that they lived in the same town as the respondents. Other times, the interviewers reported that they were from out of state. In other words, half the time the participants thought they were talking to someone like them whereas the other half they believed that they were being interviewed by a football foreigner. The us-them effect was much stronger when talking with the outsider. When reminded of competing groups, our own membership in a successful group becomes more important.

The need to be part of a group is most likely to occur when an outside group threatens the very existence of our own group. Nothing galvanizes people more quickly than a physical attack against them. In the United States, the September 11, 2001, attacks provided a powerful example. In the first days of September, George W. Bush had been president for less than eight months and had an approval rating of about 54 percent. Within a week of the 9/11 attacks, his ratings skyrocketed to almost 90 percent. In every city in the country, people flew American flags and all the news stations discussed the outpouring of patriotism and national pride.

You may recall the large-scale project that we conducted on thousands of blog entries that spanned a four-month period starting two months before 9/11. Within minutes of the attacks, LiveJournal.com bloggers started switching from the use of I-words to we-words. In fact, this pattern continued for several weeks afterward. Coinciding with the elevation in we-words was the brief drop but then long-term increase in positive emotion words. A horrible trauma such as 9/11 has the unintended effect of bringing people together, making them less self-focused, and within a few days, making them more happy.

That natural and man-made disasters can bring people together is not a new idea. When residents of London were enduring an extended period of nightly bombings by the Germans in World War II, several indicators pointed to the much tighter social bonds among the people. One frequently cited statistic is that suicide rates dropped dramatically during this period. More recent data found large drops in suicide rates in the weeks after September 11, 2001, and, in the United Kingdom, after the 2006 subway bombings. You will recall similar findings discussed earlier surrounding the eruption of the Mount St. Helens volcano in 1980. Those from cities that had suffered the most damage later reported they were glad that it had happened in their lifetime and that the eruption had brought the community together.

Study after study has found the same pattern of effects, many of which have been mentioned elsewhere in the book. The we-jump and I-drop phenomenon is as reliable as, well, taxes and death. Examples include:

• Newspaper articles, letters to the editors of newspapers, and online tributes following the A&M bonfire tragedy that killed twelve students in 1999. The disaster galvanized the student body, resulting in tighter social connections than ever before. Illness rates over the next six months dropped 40 percent from the year before, unlike all other large universities in the region.

• Online chat groups talking about the death of Princess Diana in a car accident in 1997. The effect lasted about a week.

• Online bulletin boards discussing the Oklahoma City bombing that killed 168 people in 1995. Even in the earliest days of shared online communication, people rushed to talk about their feelings.

• Hundreds of essays of college students in New Orleans four months after Hurricane Katrina destroyed the city.

• Hundreds of interviews and surveys of people across Spain in the weeks after the March 11, 2004, Madrid subway bombings.

• Google Internet searches in England following the London underground bombings in 2005, Pakistan after the assassination of Benazir Bhutto in 2007, India after the attacks in Mumbai in 2008, and Poland after the airline crash that killed the country’s president and other leaders in 2010, which all showed comparable trends.

THE USE OF we-words and the sense of group solidarity is not something that just occurs when people are threatened. Much like the football example, people embrace their group identity when it succeeds or behaves admirably. Google Labs has developed a marvelous application called Google Trends (www.google.com/trends) that allows users to track the words people use when searching the Internet. With it, anyone can see how particular cities, states, or countries use words over time. Using Google Trends, it is easy to come up with examples of increased we-word use during times of cultural pride. Nationwide, use of we-words increased in the United States following the election of Barack Obama in 2008 and in Britain after the success of the Conservatives in their 2010 national election. In Canada, use of we-words spiked in February 2010, during the Winter Olympics, which it hosted.

THE IMPORTANCE AND LIMITS OF GROUP IDENTITY

We-words tell us about group identity. By analyzing them closely, it is possible to get a sense of the speakers’ connections with others. Knowing if someone feels that they are an integral part of a marriage, a family, their company, their community, or their country is valuable information. In fact, many psychologists and sociologists have devoted their careers to understanding group identity. People who identify with a group are simply more loyal to it. They tend to rely on people in their group and distrust people outside it. Group identity has frequently been associated with stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Many family feuds, regional battles, instances of genocide, and world wars have been fought where group identities served as the rallying cries.

If you are interested in groups and how they work, knowing about the people’s identities is a good first step. But it’s only part of the story. Just because I am a member of various types of groups doesn’t mean that I necessarily like all the people in each group, would work well with them, or would even like to eat lunch with them. To really understand how groups work, it is important to track how they communicate with each other.

BEYOND GROUP IDENTITY: CAPTURING GROUP DYNAMICS

It’s easy to forget that the reason language evolved was so we could communicate with other people. To appreciate how a group functions, look at how members of the group interact with one another. When people in the group are talking, are other members of the group listening? When they are working on problems together, do they tend to talk in similar ways?

In the chapter dealing with close relationships, the topic of language style matching, or LSM, was discussed. LSM measures if two people are in synch with one another by looking at how similarly they use stealth words—personal pronouns, articles, auxiliary verbs, and the like. The more similarly two members of a couple use stealth words when talking, e-mailing, or IMing, the more the couple is “clicking” and the more likely the couple will still be together a few months later.

As with couples, all groups can vary in the degree to which they are cohesive, in synch, or clicking. You may have recently had dinner with a group of friends and marveled at how your group was in perfect harmony. Meeting again a week later, the same group may have been completely out of step for no apparent reason. Most of us have had similar ups and downs with group meetings at work, at home, or in online chats. By measuring each person’s relative use of stealth words in these interactions, we can begin to get a sense of how well the group is working and even identify where the problems might be.

SMALL WORKING GROUPS: SOLIDARITY AND PRODUCTIVITY

Imagine that you are thrown into a work group that must come up with a solution to a complex task. As part of a business school exercise, your group must decide if it would be a good investment to buy LuProds Manufacturing Company. LuProds, you learn, has designed a new gear system for bicycles that could revolutionize the bicycle business. No one in your five-person work group knows anything about LuProds or the bicycle business. Over the next four hours, however, your group must write a report that lays out your recommendations backed up with solid information. To add to the pressure, there are ten other groups doing the same task and it is imperative that your group’s performance is among the best.

To succeed on a task like this, each group member must take on an independent task. Someone must learn something about the bicycle business, the gear business, the economic history of LuProds, its competitors, the quality of LuProds’s management team, and potential other LuProds buyers. The team members must work closely together in a coordinated way to come up with an overall recommendation based on all the information available.

What makes for a good working group? Even within the first few minutes of your group being together, we can begin to predict how it will do on the task. This may not surprise you but the ways the group members use function words with each other is one of the best predictors. Variations of this project have been run in business schools and psychology departments around the world. In two studies, my colleagues and I calculated style matching scores for each person in the group. So, for example, if there were five people in the group, we could determine the degree to which each of the five people matched with the average of everyone else in the group. The average style matching, or LSM, score for each group tapped the degree to which the entire group was talking in similar ways. The more group members talked alike, the more cohesive the group. In other words, higher LSM scores reflected more tightly knit groups.

More important, style matching was related to how well the group performed. If people in a group are using similar function words at similar rates, the team performs better. Even before the groups turned in their answers, our language analyses could make reasonable predictions about the ultimate success of the different groups. At least in controlled laboratory settings, the use of stealth words such as pronouns and prepositions among the people in the group showed that the participants were all on the same page—they all shared common assumptions about the task and what needed to be done.

LARGER REAL-WORLD GROUPS: WIKIPEDIA

Lab studies of group behavior tell us how people might behave in more natural settings. How many times in your life will you be in a group with four twenty-year-olds making a major business decision on a topic you know nothing about over a four-hour period? Does language style matching predict success in actual real-world groups? The answer is in Wikipedia.

Created in 2001, Wikipedia is an online encyclopedia-like information source that has several million articles. Many of the articles are expertly written and have been carefully edited by dozens, sometimes hundreds of people. For the most commonly read articles, an elaborate informal review takes place. Often, a single person will begin an article on a particular topic. If it is a topic of interest, others will visit the site and frequently make changes to the original article. In many ways, a Wikipedia article is really two articles. The casual visitor sees only the final product. However, by clicking on the “discussion” tab, it is possible to find conversations among the various contributors. These interactions are often quite professional, sometimes detailed and thorough, but occasionally downright rude and nasty.

What makes Wikipedia amazing is that it reflects a form of intellectual democracy that actually works. Although many scholars would be loath to admit it, Wikipedia is often the first professional site they visit to learn about a new topic. It is also a rich source of language data for someone interested in how groups work. In fact, it so intrigued one of my graduate students, Yla Tausczik, that she enlisted the help of the University of Texas at Austin’s supercomputer team to download all of Wikipedia, including the behind-the-scenes conversations—a nontrivial task, I might add.

For starters, Yla identified about a hundred American cities that had relatively extensive Wikipedia entries. The cities were all midsized, ranging in population from about 500,000 to 1.5 million people. Each city’s site had been edited multiple times by at least fifty different people over several years, so that there had been lengthy discussions concerning the entries. In addition to the articles themselves, each entry had gone through a review process. Indeed, all articles are categorized by Wikipedia along a continuum from “stub” (meaning not worthy of even being called an entry) to exemplary.

The degree to which the various editors used similar language in communicating with each other reflected higher-quality articles. Just as in the lab studies, teams of Wikipedia authors and editors who are in synch with each other—as measured by their similar use of stealth words—produce the best, most authoritative articles. Language style matching in the real world reflects better real-world products.

EVEN LARGER REAL-WORLD GROUPS: COMMUNITIES AND CRAIGSLIST

If we can examine the cohesiveness and interconnections of a changing group of editors on Wikipedia, why not look at real communities? Some towns are more tightly knit than others. Most of us have occasionally visited towns or neighborhoods where people appeared to be remarkably similar in their opinions, food preferences, and social behaviors. In others, virtually no one seems to know their neighbors or has a sense of the history or values of their community.

The Wikipedia project hints that it might be possible to assess the connections between people by simply measuring how people in a community use language. Another amazing Internet development has been the growth of the site Craigslist.org. In most U.S. cities, Craigslist allows people to buy, sell, and give away a large number of goods and services. The ads themselves are free and people can write as much as they like and even include pictures. The demise of many American print newspapers has been attributed, in part, to Craigslist in that people are more likely to sell their cars, rent their houses, or give away their puppies on Craigslist than use paid classified advertisements in their newspaper.

In 2008, my students and I saved copies of all Craigslist ads in thirty different midsize communities across the United States. Because there are so many categories of ads, we only looked at ads for cars, furniture, and roommates. Within each category, we analyzed between six thousand and ten thousand ads and evaluated how people in the different cities used function words. More specifically, we were curious how similarly different communities used pronouns, prepositions, articles, etc.

The results were fascinating. In several of the communities, people tended to write their ads using the same language style as their neighbors. In Portland, people generally wrote in a personal style with a slight negative emotional tone. People in Salt Lake City, on the other hand, were exceptionally upbeat in their ads. Although Craigslist writers in Portland and Salt Lake City may have had distinctive styles, within each city, people were thinking about their ads in the same ways. In contrast, residents of Bakersfield, California, and Greensboro, North Carolina, were much more scattershot in their writing styles—meaning some people may have been very formal in their writing and others very informal. They simply didn’t speak with one voice.

Using a method similar to language style matching, we were able to calculate the degree to which residents in any given town used language in similar ways. The findings suggested that the more similar the community’s use of language, the more cohesive the city.

As you look at the table that lists the ten most and least linguistically cohesive communities, the difference between them may not be immediately obvious. It’s not a matter of north versus south, liberal versus conservative, rich versus poor, or even a function of the towns’ racial makeup, age distribution, or migration into or out of the city. Rather, one of the most striking differences between the two lists is that the most cohesive communities have higher and more equal income distributions than the least cohesive. Using a statistic called a Gini coefficient, demographers can determine the degree to which wealth is spread around in any given city, state, or country. Cities where the residents use language in similar ways tend to be communities that are more similar in terms of their incomes. The bigger the split between the rich and poor of a community, the more varied their writing styles for Craigslist ads.

RANKING OF COMMUNITIES BY LANGUAGE STYLE MATCHING STATISTICS FOR CRAIGSLIST ADS |

|

MOST LINGUISTICALLY COHESIVE (TOP 10) |

LEAST LINGUISTICALLY COHESIVE (BOTTOM 10) |

Portland, Oregon |

Bakersfield, California |

Salt Lake City, Utah |

Greensboro, North Carolina |

Raleigh, North Carolina |

Louisville, Kentucky |

Birmingham, Alabama |

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

Rochester, New York |

Dayton, Ohio |

Hartford, Connecticut |

El Paso, Texas |

New Orleans, Louisiana |

Jacksonville, Florida |

Richmond, Virginia |

Columbia, South Carolina |

Worcester, Massachusetts |

Tulsa, Oklahoma |

Tucson, Arizona |

Albany, New York |

Note: Cohesiveness is calculated by the degree to which people in the various communities used function words at comparable levels in their Craigslist ads.

You can see why the Gini statistic is important. In communities where there is a much larger split between the rich and the poor, it’s less likely that the different elements of the city will interact. As the range of income within a town becomes smaller, the residents will likely have more in common with one another and should talk more with others. Not coincidentally, they should also have more objects and services that others in the community would want to exchange on Craigslist.

The magic of this project is not about the links between income distributions and social patterns in cities. Rather, it shows how words in the most mundane of places can reveal important information about a community’s social ties. All groups, whether families, work groups, companies, or entire cities, leave trails of their social and psychological lives behind in the words their members use in communicating with each other. Words are one of the human-made elements that connect our thoughts and ideas across people. By tracking our words, we get a sense of the social fabric.

GROUP SPOTTING: HOW WORDS REVEAL WHAT A GROUP IS DOING AND WHERE IT IS

Consider what we know so far. Individuals use words—especially pronouns—to signify their sense of belongingness to a wide range of ever-shifting groups. Whereas we-ness measures reflect feelings of group identity, synchrony measures, such as language style matching, tap a shared worldview by the group members.

Taken together, the various findings point to the shared mind-set of most groups. Within any group—whether a family, school, work team, or even a community—people soon start talking alike. In small groups, they discuss the same topics with each other, and in a sense, it isn’t too shocking that their function words are similar. But as groups get larger and not everyone necessarily talks with everyone else, it is impressive that the group still maintains its own linguistic style.

Sociolinguists would not be surprised that large groups share similar linguistic styles. There is now a generation of important research tracking how neighborhoods, cities, and entire regions of a country begin to develop their own unique accents. Further, people can usually modulate their accents depending on who they are talking with. If my wife gets a phone call at home, I can usually make a reasonable guess who she is talking to by her cadence, volume, tone, and even accent. If my brain were wired differently, I could probably also hear her function word use and make even better guesses.

Think about the implications of the “contagion” of function word use. If function words really work a bit like accents, our language should vary depending on the group we are in, what the group is likely doing, and perhaps even where the group resides. We may not be aware of it but we likely shift in our use of function words depending on what groups we happen to be in and what the groups happen to be doing.

Taken together, every group has its own linguistic fingerprint. Parts of the fingerprint may reveal how well the group works together and the degree to which its members identify with the group. Other parts of the fingerprint reflect how the group thinks and feels and how emotionally open, formal, detached, and so forth it is. In theory, the language from any group gathering should provide clues to the dynamics of the group and its members.

WORD CATCHING IN PUBLIC PLACES: THE SOCIAL ECOLOGY OF WORDS

Groups, of course, have different purposes. Sometimes, we are in groups that work on a task, play a game, or just socialize. Different tasks demand different ways of speaking. By analyzing the words that different group tasks demand, we can get a new perspective on the nature of the groups themselves.

Several years ago, my students and I carried digital recorders to various public places. We would slowly walk through restaurants, crowded hallways, post offices, college basketball and young children’s soccer games, classrooms, and poolrooms with our recorders held high. The “word catching” project had very few rules other than we had to keep moving the entire time and not hang around any given conversation for more than a few seconds. The goal was simply to catch words in different types of locations. Over the years, we collected additional language samples that included people working in groups and places where strangers were meeting for the first time. One by one, every language sample was transcribed and added to our Word Catcher archive.

“Why bother doing such a screwy project?” many of my friends and colleagues would often ask. I wanted to know if and how people changed the ways they used words depending on the situations they were in. The results were clear: Every context has its own linguistic fingerprint.

Spend a minute and ponder the findings in the “Language of Situations” table. Every general situation is associated with a very different word pattern. When people are seated and talking with others over lunch or dinner, or even seated in a park, they use high rates of I-words, he-she words, past tense, and negations and, at the same time, very low rates of articles. This may sound obscure but it’s not. These word patterns suggest storytelling. And, in fact, reading the transcripts, it is obvious that people who are seated and talking with others are telling stories about themselves and others.

In sports settings, the language is more upbeat and lacking in introspection. Whether playing billiards or watching a sporting event, both men and women are immersed in the game and not focused on themselves. They are living in the moment while feeling as though they are part of a group. This is probably the allure of sports—they serve as an escape from the self. There is an interesting parallel with the language of work groups. They, too, use high rates of we-words and low rates of I-words. The big difference is that work groups use far more complex language and tend to express more negative feelings.

People who are talking with others while walking around are personal, upbeat, and superficial. “Hey, how ya doing? I’m going to Serena’s later. Things are going good. Later, dude.” No deep analytic thinking here—just maintaining a friendly public face. It’s interesting to compare the superficial people in motion with strangers who happen to be waiting for an experiment or are thrown together in a room to simply get to know each other. Like people in motion, strangers talking to each other tend to be upbeat. They are different in being less personal and more vague in their claims.

These same language patterns appear for online chat rooms as well. Chat rooms for strangers trying to meet others use words like our stranger groups. People in chat rooms devoted to sports talk like real people at real sporting events. And chat rooms made up of people who know each other have conversations that use words similar to those among friends at dinner.

To get a sense of how different the language of these contexts is, imagine that we gave our computer hundreds of new transcripts from recordings across similar situations. How well could the computer categorize which language went with which situation? In this example, there are five different contexts or situations, meaning that a computer should correctly assign language samples to the right category 20 percent of the time by chance alone. Our computers do much better, averaging 84 percent correct.

Think about the logic of these findings. The situations we are in define the words we use. Imagine spending a weekend with your friends. If you go to a sporting event, you will use one set of words; you then go to a bar and you call forth a different group of words. All of a sudden, you find yourselves in a grocery store and yet another pattern of words is exchanged. The effects are so strong and predictable, one could even claim that the situations you are in demand that you talk in a certain way. OK, “demand” is a little strong. Nevertheless, where we are and what we are doing primes us to think and talk in highly specific ways.

On the surface, this may sound trivial. When playing or watching sports, people tend to talk about the game. When eating dinner with friends, most of us talk about shared friends or experiences from the past. Contexts or situations dictate the topics of conversation, which undoubtedly influence people’s use of stealth or function words. But there is more to it. Function words tell us the ways that groups and the people who inhabit them are paying attention to their worlds, relating to others, thinking, and feeling.

The word-catching studies also provide an interesting and almost upside-down way of thinking about stealth words. Most of this chapter and book has been devoted to showing how the words people use reflect who they are. These same words can also tell us where people are and what they are doing. Feed the transcript of a conversation into the right computer and it will tell you about the individuals in the conversation, their relationships, and their situation.

TRACKING THE GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION OF GROUPS

This is where things start to get a little creepy. If groups of people tend to talk and write in similar ways, it should be possible to estimate the physical location of the groups. This goes beyond estimating if someone is at the mall, in a park, or eating in a restaurant. By using both content and function words, it is possible to make educated guesses about which particular mall, park, or restaurant the speakers happen to be visiting.

The logic of linguistic tracking is similar to that of identifying accents. Depending on what country you live in, you probably do better than chance in picking out which region a speaker hails from. In the United States, the southern drawl, the midwestern twang, and the New York dialect can often be spotted within a few seconds by listeners. Computerized text analysis programs, of course, don’t analyze accents but instead focus on specific words or word patterns that may be common to different geographic regions.

Regional differences in the naming of things exist for a large array of foods, objects, and behaviors. If you want a soft drink in the Northeast, you will likely ask for a soda, in the South you will ask for a Coke (meaning any type of soft drink—not just Coca-Cola), and in the Midwest, a pop. Depending on where you live, you might refer to that green leafy herb in salsa or Vietnamese pho as cilantro, Mexican parsley, Chinese parsley, or coriander. If you don’t want the truck in front of you to splash mud on your front windshield, you better hope that it is equipped with mud flaps (in the West), splash guards (in the Midwest), or splash aprons (in the East). And if you are driving in England, hope it has mud flaps (two words), or in Australia, mudflaps (one word). Later, when you go for a row in your canoe, be careful because you don’t want it to tip (U.S. East and West) or tump (U.S. South) over.

One can imagine that by cataloging regional names, we could begin to isolate where people are from. All that would be needed would be to wait until speakers or writers mention their words for soft drinks, spices, or how their boats rolled over. Instead of waiting for relatively obscure words or topics to emerge, it might be more efficient to track more common words. Function words, perhaps?

AS WE’VE SEEN, stealth words vary by context. It also happens that they can vary according to the geographical regions. Some regional differences in function word use are well known. For example, if people are talking to several of their friends, they might refer to them as “all of you” if from Seattle, “youse guys” if from New York, “y’all” if from the American South, or even “yat” in Louisiana (as in “Where are you at?”).

Even in relatively formal writing, regional differences exist in function word use. Cindy Chung and I had the opportunity to test this idea using thousands of essays people had written in response to the nationally syndicated radio program This I Believe. The original version of This I Believe ran briefly in the 1950s with journalist and radio commentator Edward R. Murrow. Over the course of a couple of years, Murrow invited some of the cultural leaders of the time to summarize their most important beliefs. The weekly broadcasts of politicians, sports stars, scientists, philosophers, and others captured the imagination of radio listeners. In 2005, Jay Allison and Dan Gediman resurrected the idea for National Public Radio. Rather than relying on celebrities, regular listeners were encouraged to contribute their own This I Believe essays. Over a four-year period, over seventy thousand essays were submitted, although only about two hundred were ever read on air. Most of the essays were eventually posted online for the public to read (www.thisibelieve.org).

Working with Allison and Gediman, we analyzed about 37,500 essays. A number of the stories were riveting, some tragic, many funny, most touching and inspirational. Regional differences emerged in terms of the topics of the essays themselves. Stories about sports were most common in the Midwest, racial issues in the South, and science in the Northeast.

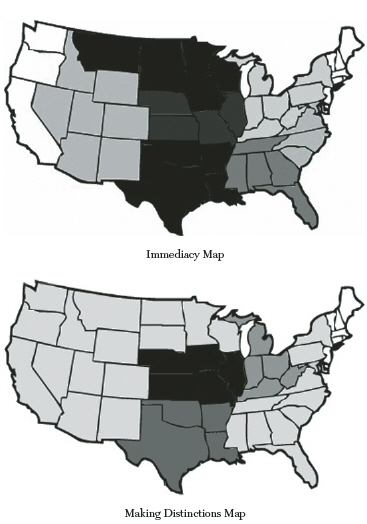

Relative use of words within an immediacy cluster (I-words, short words, present-tense verbs, nonuse of articles) and making-distinction cluster (exclusive words, negations, causal words, nonuse of inclusive words). Darker regions reflect higher usage. Language samples are based on about 37,500 U.S. This I Believe essays.

Not only did people differ in their topics, but they also differed in terms of their function words. As you can see on the top map, people in the middle of the country tended to use the highest rates of I-words, present-tense verbs, and short words. As you might recall from earlier chapters, this constellation of words reflects psychological immediacy, wherein writers tend to be in the here and now. The darker areas reflect higher rates of immediacy. Contributors from the Northeast and the West were the least personal and social in their writing and the most concrete. These low levels of immediacy reflect a language style of psychological distance and formality.

Recall from earlier chapters that function words often clump together in a way that reflects analytic thinking. People who think analytically often make distinctions between ideas. In making distinctions, it is necessary to use words such as conjunctions (but, if, or), negations (no, not), and prepositions (with, over). In the bottom map, people in the middle of the country make the most distinctions and those in the far Northeast make the fewest.

What accounts for these regional differences? As we have seen with the language style matching, people quickly adjust their speaking styles to others around them. The more time spent conversing, the more individuals begin seeing their worlds in similar ways. As a general rule, my neighbors have the same weather, eat similar foods, share the same community events, and deal with the same schools, tax collectors, stores, and bureaucracies as I do. The people in my community share many of the same issues with those in the next town and, to a certain degree, with those in the neighboring state. But as I travel farther and farther away from home, the weather, food, cultures, and concerns begin to change. As the social and physical environments change, so do the ways people approach their worlds and talk with others.

ALTHOUGH LANGUAGE DIFFERENCES should become more pronounced over greater distances, some variations in language can spring up in neighborhoods separated by only a few blocks where weather, terrain, ethnicity, social class, and every other factor is similar. I grew up in an oil-boom town in West Texas, where most families would move in for about four years before being transferred elsewhere. Even with the constant migration, new neighborhood children would quickly adopt accents and slang consistent with that neighborhood.

Even within schools, researchers have been able to isolate different language patterns among different subgroups. In an important analysis of a Detroit high school in the early 1980s, Penelope Eckert demonstrated that the language of the school’s jocks was as distinctive as that of its burnouts. Not unlike most secondary schools in the world, the different tightly knit groups adopted their own language styles in a way that reflected their group’s identity.

It’s not much of a stretch to imagine that different schools in the same geographical region could develop their own language styles. We have found evidence for this by analyzing over fifty thousand college admissions essays submitted by students who were accepted at the University of Texas at Austin over several years. Working with the school’s admissions office, linguist David Beaver and I looked at about two thousand essays from students from nine different high schools surrounding a single large metropolitan area in Texas. The students from the various high schools did equally well in high school and their first year in college and varied only modestly in their social class and ethnic makeup. Nevertheless, the ways they used pronouns, articles, prepositions, and other function words in their essays differed from school to school. In other words, each school had its own linguistic fingerprint.

College admissions essays, like This I Believe stories, are unique forms of writing. Most people will write something like them only a few times in their lives—if ever. Usually, the authors sit alone in their rooms (or coffee shops) and reflect on some of the bigger issues in their lives. Their stories reflect their families, their friends and community, and their society. The inner voices that guide their word choices are driven by the ways they think, what they attend to, their emotional states at the time, and their language history.

It is little wonder that self-reflective essays mirror people’s sense of place and the groups with which they spend most of their time. Even with relatively crude computer models, we can do much better than chance at estimating which part of the country, what city, and possibly what part of a city a person is from by the ways they use function words in their essays. If we are analyzing transcripts of people in conversations, these same function words provide hints to what people are doing, the situations they are in, and the nature of their connections to the people around them.

If you have paranoid tendencies, know that it is unlikely that a function-word-based predator drone will ever be developed. The words we use have always reflected who we are, where we are, and what we are doing. The who, where, and what have historically been obvious. Prior to the written word, if I were speaking with you, we would both know that I was talking (who), our location (where), and our current actions (what). Only through the fluke of technological advancements have we had a period where the who, where, and what of communicating became opaque. The delicious irony is that with additional advances in technology, we may eventually be able to determine the who, where, and what of communication at levels comparable to our ancestors more than five thousand years ago.

THIS CHAPTER HAS explored how the words people use in groups can reveal something about the groups themselves. Use of we-words by group members often suggests that the members identify with their group. Over time, as people become more comfortable with their group, everyone tends to use we-words more. When groups succeed or are threatened from the outside, group identity increases, with a corresponding increase in the use of we-words.

We-words reflect group identity but not the degree to which a group works well together. It may be possible to increase a team’s sense of identity, but that doesn’t mean the team will actually perform any better. There may be no I in team but there is no we in team either. Language analyses suggest that for groups to work best, they must think alike and pay close attention to the other team members. In all likelihood, language style matching reflects mutual interest and respect among different people in a group.

The definition of a group has been used rather loosely in this chapter. This is OK: I’m a social psychologist. What is particularly intriguing is that similar processes for the use of we-words and language style matching are apparent among dating couples, working laboratory groups, real-world work groups, online communities, and entire schools, communities, and societies. The unifying theme is that all of these groups use language to communicate. Words are the common currency of interaction whether written or spoken.

Finally, just as words of group members reveal information about group processes, they also tell us something about what groups are doing and where they are. In an odd way, function word usage is highly contagious. Whether in couples, small groups, neighborhoods, or communities, people tend to adopt the language styles of the people around them. Our words, especially our function words, inadvertently reveal what we are doing and where we are. Just as our accents, body language, and clothes reveal our social and psychological selves, so do our words.

If you are a private investigator, put away your spyglass. Instead, boot up your computer and start counting words.