Like the mythological “force” of Star Wars movies, book restoration skills are a neutral energy that can be used for good or evil. But some of these skills are more susceptible to being used by the dark side, facsimiles and sophistications among them. To be clear, though, until the element of fraudulent intent is introduced, facsimiles and sophistications are just tools in the restoration toolbox. This chapter includes tips to help you avoid inadvertently buying books that have been touched by the dark side. It also contains some words of wisdom from a few book experts, my own facsimile confession, and the only example of actual fraud I have ever had come through my shop.

Facsimiles

There is a huge difference between making an “exact” copy and making a decent placeholder for a missing page or plate. John Carter has called these “exact” copies a nightmare for collectors. He suggests that there should be a distinction between the term “reproduction” (as decent placeholder) from what he calls a “true facsimile.”1 I agree. I believe that if these terms were added to all the major bookseller glossaries that it might catch on and make a difference, but until then, the terms are used interchangeably, and we must rely on details for clarity.

While I sympathize with the frustration of collectors regarding facsimiles, I also understand the artist’s drive to do their best work. It seems that no matter how many stories are told about the horror of being duped by a good facsimile, most collectors will still do whatever it takes to procure the best possible version of the books they want to collect. No matter who is at “fault” for creating the copies, the important thing is to know that they exist in the world, and to learn what you can so you can identify them.

One of the most important aspects of identifying facsimiles is knowing something about how printing works. Bernard Middleton, in his paper “Facsimile Printing for Antiquarian Books,”2 lists about seven different methods that have been used to create reproductions over the years. Apparently, good quality facsimiles only started in 1855, when Vincent Figgins created an entire facsimile set of type to match the original set in order to reproduce whole books by William Caxton as well as to replace missing leaves.

This intensity of labor to recreate a page that will have the same qualities as the original is just one of the reasons that good quality facsimiles are relatively rare even now. Even with more modern technologies such as Photoshop and color-calibrated printing methods, nearly perfect copies cannot be accomplished without skill, specialized knowledge, specialized materials and a lot of time. Here is a list of some of the methods of facsimile creation: pen tracing (also used to forge signatures of course), anastatic printing (which can actually destroy the original page it is copied from), lithography and photolithography, zincography (also with magnesium blocks), all the way up to photocopying and line-block printing. There are many problems to contend with along the way such as scale, show-through, registration, paper jams, and inept printers damaging the original.

A reproduction can be as obvious as a standard photocopy of a page from another copy of the same book. These need no special knowledge to identify. They will stick out like a sore thumb. The potential for confusion starts as soon as any effort has been put in to make the copy blend in. There are a couple of simple ways to do this. For instance, the paper can be matched in kind and Photoshop can be used to clean up unwanted marks and adjust colors. Even I have to admit that it all starts sounding like tricks and cheats, but I have been on the creation side and from there it all feels like clever solutions to complicated problems. I could go on about how these things are done but this book is not about teaching you how to make facsimiles. Instead let’s look at the telltale signs to help you identify the three main kinds of facsimiles: pages, book covers, and dust jackets.

Facsimile Pages: Telltales

Paper: grain direction

Handmade paper is made by swooshing plant fibers around in water, scooping the fibers out in a shallow screened mold, and then letting the fibers settle. Then they are couched (transferred) onto wool felts, pressed and then air-dried. This is a gross oversimplification but what I want you to get out of this description is that, as the fibers are being shaken around in the shallow mold, they tend to line up in one direction more than the other which determines the grain direction. This means the paper will fold more easily in one direction than the other. If the suspect page curves differently than the other pages, it is a sign the grain is also different.

Laid versus wove handmade paper

Laid paper is created by casting paper pulp on a screen hand mold with thicker wires running at right angles to thinner wires. The thin wires are the laid lines and the thicker wires are the chain lines. The specific pattern created by these two different thicknesses of wires is much like a bamboo placemat at the dinner table.

Wove paper is made with a mold that is finely woven with none of the thicker chain line wires. This finer weave of paper was first created in the mid-1700s to create better quality printing. Most modern papers, such as your typical printer paper, is wove rather than laid.

This is useful to be aware of because if a book were printed originally on all laid paper and someone puts a facsimile in that was printed on wove paper, you don’t even need a magnifying glass to see the difference, although holding the paper up to the light may help.

Clay-coated paper

Be aware that color plates are frequently printed on different paper than the text-block. Because of the need for great image quality, color plates are often printed on clay-coated paper. This is the extra glossy, heavy paper found frequently in art and photography books. This paper is hard to duplicate and is not something you can find at your local office supply store. It also gets ruined easily if it gets wet, unlike other paper. The clay re-activates with water and sticks to the page next to it and the colors run. Colors may run on other kinds of paper as well but not as badly. It is not easy to match the color, look and feel of clay-coated original plates.

Page Color

The color of the papers may also give a change away. It is typical for the color of a plate page to be different than the color of a text page but if you compare text pages to each other or plate pages to each other you will be able to see if something stands out as obviously different. A blacklight can be used to help with this. Papers that in plain light look identical are sometimes revealed as being of different manufacture under a blacklight. Keep in mind that minor differences in the color of handmade paper (typically books before 1850) can be expected due to simple production line variations in timing and materials.

Page thickness

Look at the thickness of the pages. Use your fingers and a careful eye to see if the papers are the same thickness and texture. A new addition to a book that is on thicker or thinner paper will bend differently than the other pages and may even have been attached with the grain of the paper going the wrong way. This means it will try to curl away from the rest of the pages.

Printing qualities of replacement plates and pages

Size and placement of image: the size of an image can also be used as an indicator of origin. If a replacement comes from a photocopy of an original, a print from a digital file, or is a plate from a different edition, it is likely to be a slightly different size. Copying an image precisely is more challenging than most people think. Size and/or color differentiations are almost always present even when this copying is done professionally. You can take the measurements of the area of the printed text on a page or plate you are sure is original and then compare it to the suspect one. If you know all the original images are the same size, then this one should match exactly.

Printing registration

If there is an image/text on both sides of the paper, you can look at the registration (i.e. the alignment of the images or text) through the page. While originals may not be lined up perfectly, if you can compare a suspected facsimile with an original there may be an obvious difference. Registration that seems off is just a sign to look closer.

Kiss

If someone went to the trouble of finding paper that is from the same period and even used the same kind of printing method, there is still the “kiss” to look for. The kiss refers to the connection of the ink with the paper. The ideal kiss has no impression to speak of on the paper, but many times the printing process will leave a shallow impression when it presses the paper onto the type. A really deep impression is called a “bite.” With a magnifying glass you can look for impressions on any page that has been printed in this manner.

It is highly unlikely that someone would go to the considerable expense and time to have a real printing made of a missing page or plate. Any book valuable enough to spend that amount of money and time would also undergo an intense scrutiny of the sort that involves microscopes and chemical analysis as well as an age check. Modern copy machines using computer-guided application of inks do not have an impression because pressure is not needed to generate an image.

Some forms of book illustrations, such as engravings, are also impressed onto paper, which generates an impressed outline of the metal engraving block used. Facsimiles are not likely to have this impression.

Dot matrix

To identify modern printing methods just get out a magnifying glass. Dot matrix printing (which was first brought out in the 1920s) gives away the era. If you look very closely and see that the solid color is actually made up of tiny dots of different colors you know it was created after 1920. You can read more about this a little later in the section on dust jackets.

Page and signature attachment

Look at the attachment of the page or plate to the book. Look for signs that a page has been excised and/or replaced. One sign is an excessively glued attachment. You can also look for new added materials such as tissues, papers or even tape to make the attachment. These really only tell you that the page or plate has been detached but cannot tell you if it is integral to the original. If you can detect a stub of the original page you should definitely look harder at that page. And not only that page! There is another place to look that is not obvious at all. If a page has been removed entirely then the corresponding page that it was originally folded with (in the signature) may be vulnerable to falling out. Be sure you don’t confuse tabs that have been intentionally created to leave room for plates with stubs that indicate missing plates.

Alignment

It is important to remember that evidence of a plate being re-inserted is not the same as evidence for it being a reproduction or a swap. If a plate is put in crookedly it could be that it is original but at some point just fell out or came loose and was replaced or reset. Keep this in mind when examining a book with plates that has had work done to it.

Edge color

Another place to look for changes is the very edge of the page compared to the edges of the rest of the book. Dirt, gilt and color are all things that may have been overlooked in the replacement page edge. A quick glance at the edges may reveal a bright white line the aged page edges. Another tell is to look for an edge that is too clean. Depending on the age and use of the book there is normally a layer of dust on the top edge that will make the top edge of the text-block darker than the bottom edge. Note that sometimes edges are colored decoratively on purpose by the publisher. All the edges or even just one edge can be colored. You will want to avoid removing the color of these edges. One time, I cleaned the edges of a book only to discover later that the dull dirty brown color was meant to be there! The owner had another copy in better condition, so I was able to reference it and re-color the edge to match. If it is really dirt then a bit of mild sanding or even just brushing with a stiff brush will clean that up. If sanding is done poorly the text-block edge will be uneven and there may be a darker spot right against the end-band where it can be difficult to sand.

Page marks and stains

Another way to make sure that pages are original to the book is to look carefully at stains, ink transfers and even foxing. I have run into a variety of people using chemicals to remove these marks. It seems like an attractively simple solution to many collectors and dealers, but in reality, this is a terrible idea. There is no way to remove the chemicals (such as bleach, specifically Lysol) that you add to paper. Acidic substances will eventually cause the paper to turn brown and brittle. Stains and other marks that pass through multiple adjacent pages are one of the best ways to tell if a page or plate has been moved or changed. Look for indicators like a strong stain or foxing that extends through several pages and then suddenly stops at the page in question. This is an indication that it may be a replacement page or that the page has been removed, cleaned and reinserted.

Alternately, the new page may have a stain on it that should have bled through to an adjacent page, but has not done so because the page was stained before being excised from one book and inserted into another. A related phenomenon is called transfer. This is when the printing (either text or image) has offset onto the page next to it. Sometimes it is actually ink that has transferred and sometimes it is only the acid of the ink, causing an “acid shadow”. This is a common occurrence and frequently plates will have those thin “onion skin” pages to protect the page next to it. Sadly, these onion skin pages are often acidic themselves and need to be replaced or de-acidified.

INTERVIEW EXCERPT: JEFF WEBER: ON FACSIMILE PAGES, AND PLATES

When I interviewed Jeff Weber (whom you met earlier in Chapter Three), I asked him about his experiences with facsimiles. Here is what he had to say:

On spotting a facsimile

Jeff: I was collating some important books for a client’s collection and I came across Kircher’s Ars Magna. I was counting every page and plate and as I was going along, I came across some plates that were obviously facsimiles. Nothing in the book stated that a facsimile was present so you wouldn’t know unless you look at my description of it. The big clue to spot the facsimile is that all the original plates have an impression around the edges from the pressing process of the printing; when you are collating and you come across one with no impression you have a huge clue.

On a facsimile well done

Jeff: In 1986 I sent a book to Bernard Middleton. It was Sebastian Munster’s Horologiographia from the sixteenth-century; a massive book. We had it at Zeitlin’s (bookstore) and I bought the book myself and sent it to Middleton to re-make the title page that was missing. It was a very unusual title page in that it was all printed in gold. But the price was too expensive to re-do it in gold. Since it would just be a facsimile anyway, I agreed to having it printed in black ink. That way it would be obvious that it was a facsimile anyway. He did a very nice job with it.

On purists

Jeff: Personally, I prefer to have a complete book with a facsimile leaf rather than an incomplete one. That being said, there are exceptions where one should not meddle with a book. A book’s value relies heavily on the presence and condition of its illustrated plates, fold-out maps and other images. This value is also what makes them likely candidates for facsimiles. A book with a facsimile page is typically worth somewhat more than a book of like condition that is simply absent a page, but not nearly as valuable as a book of like condition with all its original parts. The facsimile has made it complete with all the information.

I have found that very often collectors are happy to buy books with facsimiles as long as they are stated but there are many purists that would not purchase such a book. To sell it you would have to find the right collector. That goes for re-bindings too. One example of a book that will sell in the original binding but will not sell in a new binding is a first edition of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. It will sell if it is restored, but as soon as it is not in the original binding no one wants it.

On doing research

Jeff: If you are looking to acquire a book that has illustrated plates, you would do well to consider doing some research to find out if that book is commonly missing some. You can look it up online of course but there is nothing like actually talking to a knowledgeable book dealer. Do this before you start seriously shopping. One set of books commonly known for loose or detached plates are the early editions of the Wizard of Oz series. It is possible to buy some facsimiles (of various quality) or even actual replacement pages or plates from broken books online for anywhere from $15 to $150 or more.

Facsimile Book Covers: Telltales

Stamping with replica dies

Sometimes I get the chance to restore a book by creating a facsimile piece of the cover (some of the spine or even a board). One way to create a copy of original stamping is to have a metal die made. This is made from a black and white scanned image of the lettering or decorative element as it exists on another copy of the book. This image is made from a scan of the original stamping, not of the die that did the stamping. And because the act of stamping almost always adds width to the impression the new die is less exact or, to be precise, it is slightly wider than the original. Therefore, one way to discover this new stamping is to look for lettering that is more filled-in or darker.

No depth

Another simple way to recreate spines and even boards is to scan an original copy, clean up the image in some program such as Photoshop and then print it onto appropriate paper. This only works really well for paper book covers but it can work for book-cloth books too. I have had occasion to simply copy an intact spine from one book to make a color copy onto Japanese tissue and then apply it on top of a new spine for another book that had no spine at all. There is no depth to the impression, the spine is obviously fuzzier and a bit of the image edges are cut off, but otherwise it looks a lot like the original! This is so much nicer than any label would have been.

Pristine new material

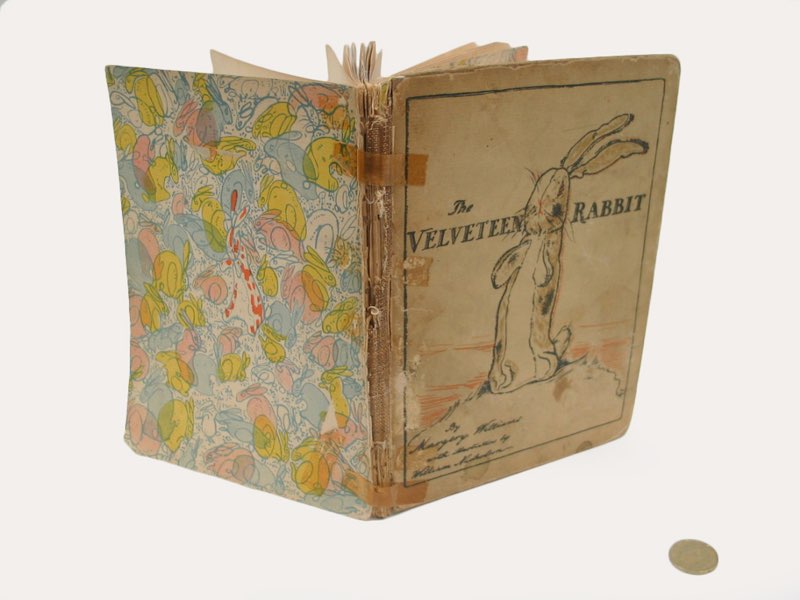

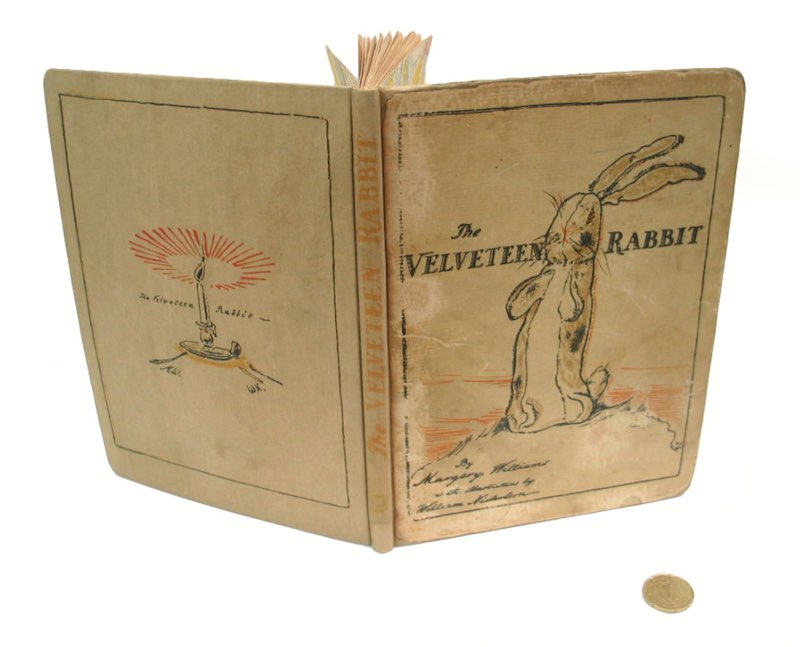

Below is an example of cover re-creation. This copy of The Velveteen Rabbit was missing the rear board and spine. I re-created it from a cleaned-up scanned image of another copy and then printed it onto similar paper, then re-bound the book. As it is you can spot the fact that the rear board is new because of the lack of damage. The front and the back simply don’t match. Inside, the rear paste-down is also a facsimile. Getting a high-quality image to do these facsimiles is not easy; it takes hours to render it into an image that will look good when printed.

I usually rely on the client to get me the image and any dimensional information. It gets expensive when I need to do the research myself. In this case the client opted for some but not all aesthetic restoration. You can see the line boxing in the front image was not restored after the tape removal. The restoration is spotted most easily at the head and tail of the front board where the new material shows. Note that the new material is pristine compared to the original front board. I did get a good match for the paper and I made sure to round the corners of the new board to match the wear of the front. But note that the rounded corners of the facsimile are not worn.

Velveteen Rabbit, new board—before

Velveteen Rabbit, new board—after

Transition Lines

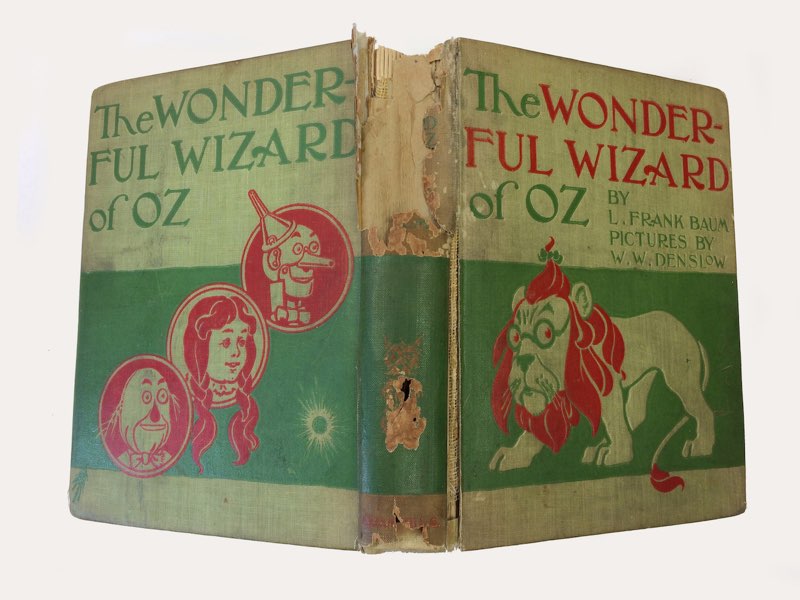

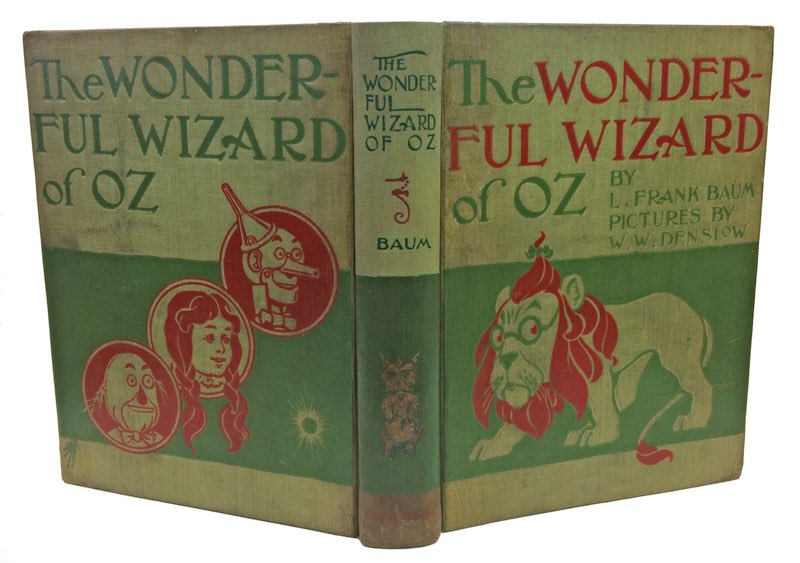

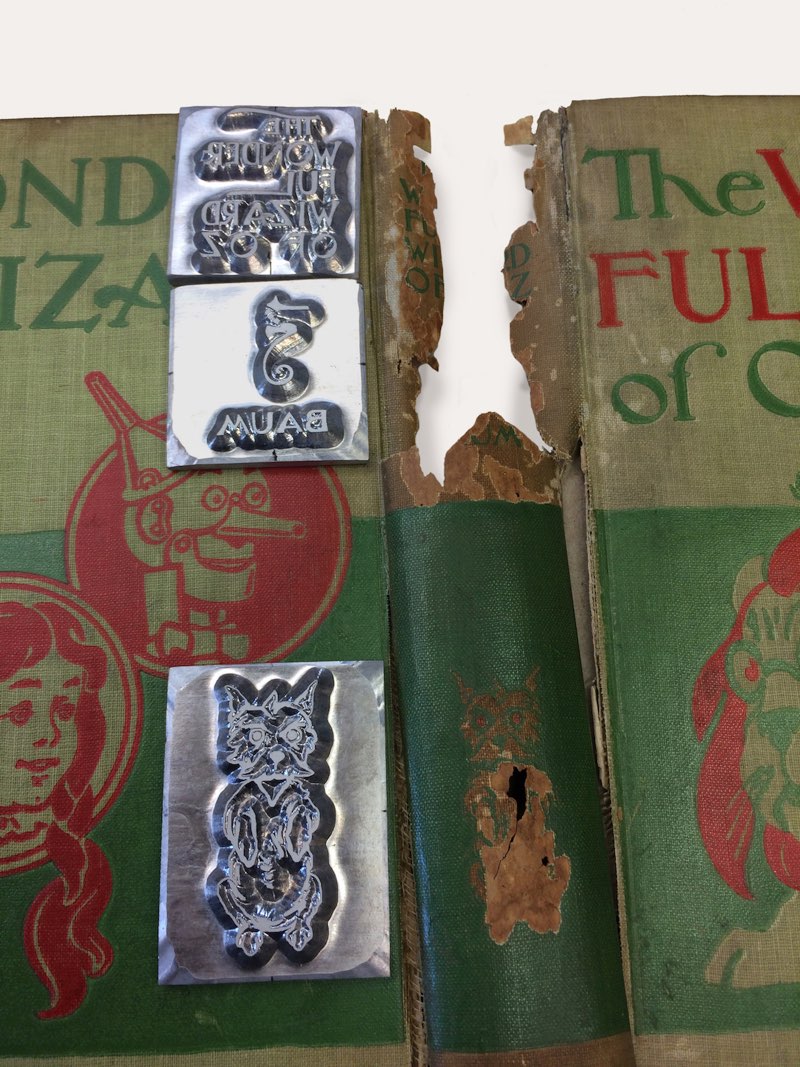

For this next example, take a look at these color photos. It is for a cloth book with a damaged spine. The top portion of the spine was damaged beyond repair partly due to a previous “repair.” It is the Wonderful Wizard of Oz first edition C binding indicated by the O inside the C of the publishing “Co.”

Wonderful Wizard of Oz facsimile spine—before

Wonderful Wizard of Oz facsimile spine—after

Wonderful Wizard of Oz facsimile spine—spine dies

The process for creating facsimile spines involves coloring cloth with acrylics to match and having metal dies made to stamp the missing title. I did this with a Kwikprint foil stamping machine and different colored foils. The new spine is applied and the lower part of the original spine is placed over it (a re-back). Here you can see the front part of the original cover (and some board) lifted for the new spine material. Lifting a bit of the board makes it so that the transition line and lumpiness are minimized. I did not age the new part of the spine so you can clearly see the transition. The edges of the cloth are sanded not only to make the transitions less obvious but because I don’t want fingers catching on the edges and pulling them up again. This facsimile was a success but it is not always worth it to go to all the effort and money required to create one. Here is a bit of my interview with one of my clients who found this out the hard way.

INTERVIEW EXCERPT: MATT S: A PRINCELY SUM

Creating a facsimile is complicated and doesn’t always “pay.” During my interview with Matt S., (whom you met earlier in Chapter Three), we reminisced about just such a project.

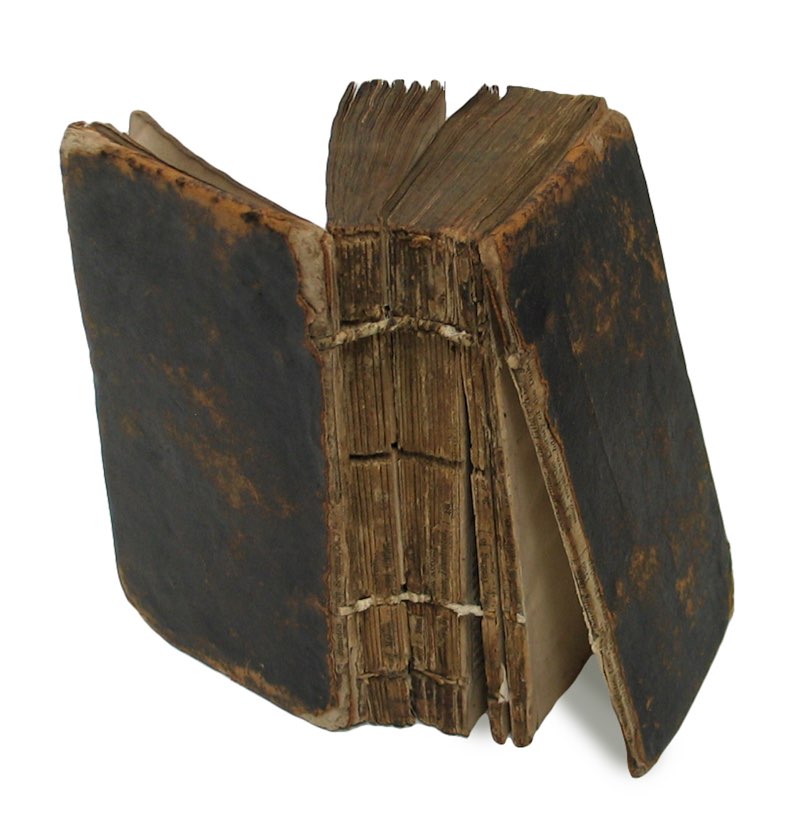

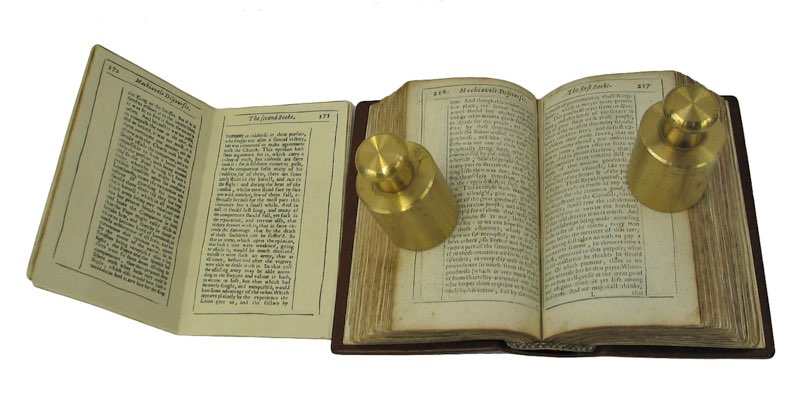

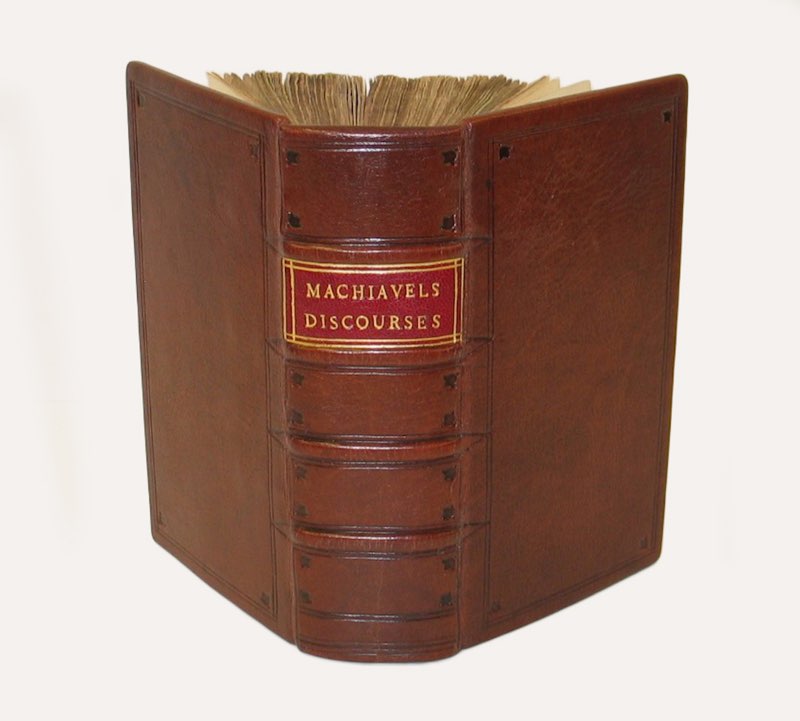

Matt: It was a little book (a sextodecimo, which measures about four by six inches), Machiavelli’s Discourses, which included The Prince. That’s the one everyone wants. There were some missing pages (about twenty) and we replaced those pages with facsimiles. You had to also create a new cover for it.

Sophia: I remember how hard it was to make those pages. I had to go to the library and get images of the missing pages from the microfiche of another copy. Then I brought those images to my graphic artist to have them cleaned up, straightened and registered so it would print correctly on a page both recto and verso. Then I had to find paper to match the original paper, get them printed and organized into quires and then sewn with the other pages and a new cover made because the old cover was gone. I made sure to color the edges of the new pages so they blended in with the old edges.

Matt: I know it was a lot of work and it looked great but I took a bit of a beating when I sold it at auction. It went through PBA Galleries. They are very thorough there. They find issues with books that I don’t even see or know about. When I send them things you have restored, I always mention it, and what they’ve done over and over is complement the work. Really though, even though I lost money on that, I heard that the person who bought the book was really happy to have it. They got a copy they could afford for their collection, and I actually felt great about saving a book that might have been lost otherwise.

Machiavelli before

Machiavelli facsimile pages next to original

Machiavelli after

Facsimile Dust Jackets: Printing Telltales

No discussion about facsimiles would be complete without mentioning the bane of the modern book collector: dust jackets. Dust jackets are known to contribute somewhere around eighty percent of the potential selling price of any book. While preservation of the dust jacket is arguably not more important than preserving the book, the same book with the dust jacket is infinitely more collectible. The story in the book may be complete on its own, but the book simply isn’t whole without its dust jacket.

To spot a facsimile dust jacket you are going to have to take it out of any protective covering to examine it thoroughly. Be careful while doing this. Fragile jackets are easily damaged in this process. If you have the opportunity to compare your suspect jacket with an original, then that will simplify this whole process. If you don’t have a confirmed original dust jacket to compare it to, don’t despair; there are some telltales to look for. Just like the telltales for pages, we have to start with the different kinds of printing used. It will help to be aware of the year each form of printing started, and then be able to differentiate the physical characteristics of the images they produce.3 Below are the different types of relevant printing.4

Letterpress

Think Gutenberg press; however, printed dust jackets only started around 1820. Letterpress can sometimes be identified because of the faint impression that the type can make when it is pressed against the paper. Also, the ink is a solid color rather than tiny dots of color.

Lithography

The lithographic offset press was invented in 1875, which allowed commercial applications for lithography. Look for solid colors (no dots). The dust jacket image would be focused on artwork rather than words.

Offset printing

Also known as “modern lithography,” this is the format that causes the most concern for the book collecting world because modern dust jacket facsimiles printed in this way are much harder to distinguish from originals. Offset started being used commercially in competition with letterpress around 1950. Using magnification, look for rosettes of color dots in neat lines. The dots will be varied in size and color intensification. While the direction of the line and the spacing will be consistent, the four colors of dots will be offset on a fifteen-degree rotation. Larger dots make darker or more intense colors. The space between the centers of the rosettes never changes. Too much overlap was avoided by rotating the colors within the rosettes along the lines. Offset printing uses four colors in the CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black) palette.

Laser printing

These printers came out in 1969. The laser beam scans back and forth to create the pattern. The laser attracts the toner with static electricity that is then fused onto the paper.

Inkjet printing

The advent of inkjet printers marks the beginning of all the insidious trouble with facsimiles. It became easy for anyone to whip one up and print it out. These printers became commercially viable in the late 1970s. The sprayed colored dots will appear to be random. Four to eight colors are used to create new colors by layering the dots close to each other. It is easier to see the dots when looking at transition areas. Fortunately, printers simply cannot duplicate the printed pattern of rosettes that offset printing creates due to the basic mechanics of the different machines. The best, most crisp ink jet printing must be done on very modern smooth papers, so trying to create facsimiles to match older papers on softer paper will create slightly blurred prints.

Color photocopies

Full-color photocopiers were available commercially as early as 1968, The first Kinkos opened in 1970. Photocopiers can be used to create good facsimiles but any imperfections like wrinkles or stains are also copied. Copies are limited in size to whatever paper fits in the machine, so smaller dust jackets are more likely to have facsimiles. Printed images of folds or creases will not have any actual texture. Look for these and then use your finger. If what looks like a crease has no substance, it must be a copy.

Digital printing

This started around 2000. This refers to the type of file used to print from rather than a printing method. Typically, digital files are printed with laser or inkjet printers.

Facsimile Dust Jackets: Other Telltales

Color

Having a photo of the original (if you don’t have the real thing) can help you compare colors more easily. It is very difficult to match colors for a facsimile

Age

Brand new facsimiles will not look aged. If the book is forty years old the dust jacket should similarly reflect that aging too (unless it was stored separately). Normal wear and tear can be faked to an extent on a jacket but be sure to look for corresponding wear and tear on the book cover.

Repairs or restorations

I hate to say it but all repairs must be suspect. That doesn’t make them automatically fraudulent (because you do not know the intent behind it), but repairs are always an indication you must look closer. Look for sanded or scraped areas as well as torn and repaired areas. Especially note if the repair is in the area that dust jacket facsimile makers are known to have printed their marks stating it is a facsimile. Typically, this is on the front flap.

Distressed areas

These can mask the removal of identifying marks or can be falsely created to pair up book and jacket. They can also just be areas that are distressed. Keep your wits about you when playing detective and don’t jump to conclusions. My goal is to engender more awareness rather than paranoia.

Colored papers

Some original dust jackets were printed on colored papers. Do your research before shopping. If the verso is not colored (and it was originally) then that is an easy tell.

Size

Does the jacket fit? Facsimiles can be the wrong size but original jackets will fit. Book club editions are usually a bit smaller than the original edition, so if someone is trying to transfer a dust jacket from a book club edition to the original this is how you might catch it. Also, apparently, sometimes facsimiles get trimmed (unscrupulously) to remove imperfections or identifying marks.

Chemical paper brighteners and bleaches

Blacklight will expose modern papers made after about 1940. This is when paper manufacturers started adding certain brightening chemicals to the paper making process. There are at least fifty years of dust jackets that should not have any brighteners added to the paper. Of course, if the person making the facsimile has some pre-1940s’ paper . . . .

Thickness

Use your eyes and your fingers. You know that dust jackets usually have a certain thickness. If what you are looking at feels really flimsy or too thick/stiff, be suspect! This is something you learn by handling books from various eras and paying attention to these qualities.

Finishes of the paper and printing

Is it too shiny? Not shiny enough? Most dust jackets are only shiny on the printed side and matte on the other.

The Ethics of Facsimile Dust Jackets

The following anecdote is a great example of the dust jacket facsimile dilemma. It was told to me by a bricks and mortar book dealer in the summer of 2015 and I asked them to write it down for me.

AN ETHICAL ENCOUNTER

We have a customer who came in and claimed to be an online bookseller. Mostly, he purchased old paperback Westerns from us. But, here’s the kicker: he told us that he “restores” any book that needs refurbishing. He touches up flaws, strengthens spines, and, most importantly, he told us that he has the ability to make facsimile dust jacket covers. We asked him if he documents his facsimile covers and “restorations” in his book descriptions, and suddenly he got a bit defensive and wary. He hedged, not wanting to talk about the details. We voiced our concern that his buyers may not realize that they were getting a facsimile cover. Again, he was vague about his book descriptions and left quickly.

The idea of the facsimile jackets bothered us, especially if they are not clearly marked as such. Seems just a tad dishonest, at best, and maybe touching on a little fraud? I remember, in my college days, a professor stating that there were four components of fraud: one, to knowingly make a wrong statement; two, to induce someone into a contract; three, when a person enters into the contract relying on the false statement; and, four, there is injury as a result. The above-detailed book situation made me think about the fraud components and the importance of honest business dealings. We haven’t seen that guy in a while . . . interesting.

Obviously, there are people out there taking advantage of the latest printing technologies to “upgrade” their books with facsimile dust jackets fraudulently. The part of this story that I found most curious though was the mild, wondering disapproval of the dealers. Why didn’t they get his name and report him? But to whom would they report him? The police are notorious for not taking a great interest in what is likely to amount to small-time (meaning low-dollar) book fraud, and they had no proof. It is unlikely that the guy was a member of a professional booksellers’ association with its corresponding ethics requirements.

I did ask them to get the guy’s name for me if they saw him again. My thought was that I would attempt to buy a book that had a facsimile dust jacket and prove the intent, as well as get a look at the quality of the facsimile. I wanted to see if it was obvious. Sadly, there really has to be a mindset of constant vigilance when it comes to dust jackets. Because they are simply printed pieces of paper, they are relatively easy to copy, and more than one person has figured this out.

The Marrying of Dust Jackets

Some book collectors have very strong opinions about dust jackets and not just about facsimiles. In the 2006 spring edition of The Book Collector, Nicolas Barker ostentatiously proposes his own ten commandments for dust jackets, one of which is: “Thou shalt not have any jacket but the original jacket.”5 I find this to be a noble sentiment, but full of wishful thinking. I am not sure that given two copies of the exact same book — one with an untouched jacket and a damaged book, and the other with a damaged jacket and an untouched book — that anyone could resist the impulse to swap them. I personally don’t see the harm in it if the jacket is truly from the same edition and it is identical in all ways. It is when editions are mixed that the problems start. Still, for the sake of the purists, please identify whenever such a swap has taken place.

ABAA’s Code of Ethics

It wasn’t written specifically for dust jackets, but the Code of Ethics and Standards of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA) states that members must conduct their business according to the following statement:

#5. An Association member shall vouch for the authenticity of all materials offered for sale, and shall make every reasonable effort to establish their true nature. Should it be determined that material offered as authentic is not authentic or is questionable, that material shall be returnable for a full cash refund or other mutually agreeable arrangement. Material proven to be not authentic, or of disputed or undetermined nature, shall not again be offered for sale unless all facts concerning it are disclosed in writing.6

To read the whole Code of Ethics go to http://ABAA.org. In addition to this standard, in 2003 the ABAA book fair rules were amended to specify that facsimile dust jackets must be identified prominently, and they also discouraged their display in general. As you can see, they are holding themselves responsible. But should they do more?

Other reputable resources also deplore the practice of not describing dust jackets properly. The blog, Books Tell You Why, had a post by Kristin Masters on March 30, 2011 on the subject.

Any reputable vendor or collector will clearly mark the facsimile dust-jacket itself as a reproduction to avoid a book being passed on and the last innocent recipient not being able to differentiate it from an original without expert help.

I see two problems with this demand to mark facsimiles. The first is that there is no regulatory agency to monitor and control (let alone punish) those who are creating facsimile dust jackets. The second is that the people who are most affected by it, the collectors and dealers, just need a little more information to protect themselves. They can become the expert mentioned by Ms. Masters. Of course, for truly spectacular facsimiles on books worth many thousands of dollars, extra measures should be taken to identify a jacket as original. Obviously with higher book prices, the investment justifies the extra expense to do so. For everyday collectibles, much can be done with just a magnifier, a blacklight and the effort to pay attention to details. Overly trusting collectors may lose out and be easily tricked. With all of this information on facsimile dust jackets, most of you are probably thinking they are horrible things to be avoided at all costs, but others may be suddenly wondering where you can get one for that jacket-less first edition you have on your shelf.

Buying Facsimile Dust Jackets

If you are going to knowingly buy a dust jacket facsimile you should read the website of the dealer thoroughly so you know what to expect. Mark Terry of Facsimile Dust Jackets LLC (http://dustjackets.com), is known for his above-board dealings, knowledge of copyright law, and commitment to historical preservation. He gives us a perfect example of how reproducing scarce dust jackets can be done well. That said, be aware that not every facsimile produced there is a spot-on twin to the original. Sometimes colors or sizes can be a bit off, but Mark has assured me that they are constantly working to improve things. They always print “Facsimile Dust Jacket LLC” on the front flap recto.

Another facsimile company doing good work is Phil Normand’s Recoverings (http://www.recoverings.com). He is solely focused on reproducing Edgar Rice Burroughs’ dust jackets. His attention to detail and personal artistry has made these facsimiles actually brighter and crisper than the originals. He says they are more like art than reproductions. He also marks each as a facsimile.

Make sure that when you sell your facsimile at a later date that you have clearly indicated this in the description or verbally to the buyer. Consider marking the front flap, recto side (with a soft pencil) yourself if it isn’t done already. Facsimiles that are not marked or are only marked on the verso side of the jacket make dealers have to work harder. Just think of the dealer having to physically remove every dust jacket from the protective covering to look for the word facsimile on every book that comes into a shop . . . wow. Let’s help them out and make it obvious when we can. And now I have a confession to make. Before I ever thought about facsimiles as a problem, I made my own very good facsimile and didn’t mark it at all. Here is my story.

THE CALL OF THE FACSIMILE

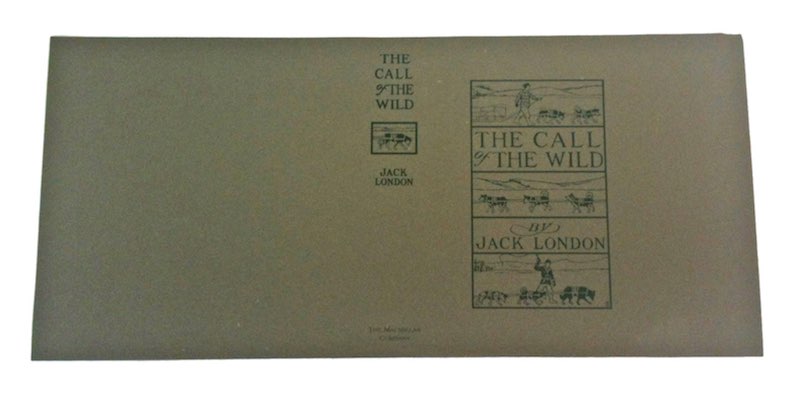

A client asked me to restore the dust jacket for a first edition of Jack London’s The Call of the Wild from 1903. This is not a modern dust jacket. It was printed on a rough greenish, gray-brown paper probably done with lithography printing, because the colors are solid rather than made up of small dots. All I had to work with was the front panel of the jacket.

The first thing I did was to look for a facsimile on the Internet. I naively thought I could just blend the facsimile with the original to create a whole jacket. I did find and buy a copy online but when it arrived it didn’t look anything at all like the original. It was printed on modern paper and was nearly pink rather than soft grayish green.

This was a setback, but I was excited to see what I could accomplish on my own for my client. Fortunately, I was able to find a nearly exact match for the paper, which is really the hardest part when it comes to making a nice facsimile. I was also able to get an image of the original spine for my graphic artist to work on. He had to line everything up so that when it printed it would come out in exactly the right spot on the paper. I had him include the front panel as well in the graphic so that I could have some extra copies of the dust jacket to work with for the future. I used an Epson pigment inkjet printer and the image came out very nicely although we had to adjust it a few times to make the colors come out right.

Call of the Wild: My facsimile dust jacket

I used one of these facsimiles I created to attach and blend with the existing front panel. Later, when my client sold it at auction, he made sure to note that a portion of it was recreated. The Call of the Wild without a dust jacket normally sells (depending on the quality) for between $200 and $400. This copy sold for $750, and my client let me know that he made a really good mark up. My point is that facsimiles and restorations are not inherently evil. You don’t need to trick people and you can still make money and make people happy.

As of this time, while writing this book, I have not yet marked up my extra copies as facsimiles. I feel that it is obvious that they are facsimiles because they are so pristine and a quick glance with a magnifier will reveal the characteristic inkjet printing dots versus the more solid color of the original. However, from a distance, sitting on someone’s shelf, it will look absolutely correct and that has a certain satisfaction to it that is worth something as long as it is not harming someone else.

Some of you no doubt will feel I should just throw the extras away entirely before they contaminate the market, and, while I sympathize with that sentiment, that is not what I am going to do. Perhaps I should write on them so that the pen indentation cannot be erased. Or maybe I should mark the back all over so that the identifying mark cannot be torn off and restored? Instead, I may go for a more elegant solution. The only identifying mark I have ever added to books that I have re-bound or restored is a pattern of three dots together in a small triangle. I place this on the inside lower inner corner of the rear board so it is not visible when the book is closed. I think this will remain my signature mark and I will put it in the same location on this facsimile dust jacket. The mark is made with three gold-tooled dots in a small triangle on the lower inner rear corner of the back panel. But of course, someone could artfully tear it off and then we are back to square one. On second thought, I think I had better write the word “facsimile” on the front flap as well.

Because of my own innocent foray into making this dust jacket facsimile, I can truly believe that there must be other examples of “very good” unidentified facsimiles out there due to the drive for artistic perfectionism rather than a malicious intent to deceive. Sadly, for collectors and dealers the result is the same: hard-to-identify facsimiles entering the market. Since there is no stopping them from flooding the market the only choice is to educate yourself to spot them, and now you know how.

Sophistications

If you google “sophisticated” you will come up with a long list of positive traits having to do with good character and taste. That definition is related to the word “sophia,” meaning “wisdom” in Greek. However, in the world of book collectors, “sophistication” has a completely different connotation. It is related to the word “sophistry” rather than sophia. According to the Oxford dictionary, sophistry is “the use of clever but false arguments, especially with the intent of deceiving.” AbeBooks in their glossary, defines sophistication thus:

A book that has been restored or worked on in order to increase its apparent value, this is often seen as an undesirable quality among collectors.7

The International Online Booksellers Association (IOBA) has a similar definition:

Sophisticated Books that have had repairs that involve making additions to the original (e.g., chips filled in and tinted to match the missing portion, replaced page corners, etc.). In the trade, an “honest” book description should disclose all “sophistications.8

In other words, if a bookseller has commissioned repairs for a book, all such repairs should be disclosed to prospective buyers in the description. However, it is possible for sophistications to have been executed on a book long before the bookseller bought it. Whether or not the bookseller was responsible for any such sophistication, failing to disclose such changes in a description is valid grounds for a buyer to return the copy to the seller (at least if the seller is with the ABAA).

The book world definition of sophistication has been around since the late 1700s so I found it interesting that the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB), an older, more established institution than the IOBA, does not include the term sophisticated in their online glossary at all.

This surprised me because the whole concept of sophistication is such a serious issue for professional antiquarian booksellers. According to the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America (ABAA)j Code of Ethics and Standards:

#3: An Association member shall be responsible for the accurate description of all material offered for sale. All significant defects, restorations, and sophistications should be clearly noted and made known to those to whom the material is offered or sold. Unless both parties agree otherwise, a full cash refund shall be made available to the purchaser of any misrepresented material.9

As you can see, this is not a term to be taken lightly. To further complicate things, I have to make a case for splitting the term into restoration materials added (such as Japanese tissue to repair a tear or paper for a new hinge) versus whole facsimile pages being added. While restoration materials are technically within the strict definition of sophistication, I think it is unhelpful to put them in the same category as facsimiles, new spines, and swapped covers because there is a significant difference between a repaired page corner and a facsimile page.

I think John Carter might have even agreed with me on this point. In his ABC for Book Collectors, he stated that the term “sophisticated” “is simply a polite synonym for doctored or faked-up.10

He doesn’t include repairs in his definition at all and instead lists as examples facsimiles, swapping title pages, and swapping book covers of different editions (remboitage). I think he takes his definition one step too far, though, when he includes removing words that state second edition.

I say this goes too far because removing identifying marks firmly moves it from an act of sophistication into the fraud category. While creating facsimiles or swapping parts of books could be an innocent means of rescuing otherwise damaged books, you can’t change edition points without deceitful intent. But before I go into fraud issues further, I want to explore a few more elements of sophistication: grangerization, contemporary bindings, remboitage, and legacy sophistications.

Grangerization

I don’t know if he started it, but in 1769 James Granger published books made intentionally with extra blank pages so that the purchaser could add their own images. However, he didn’t include any spacers, so these books wound up with a splayed fore-edge when the intent was fulfilled. If put under any pressure, the spines of these books are likely to be damaged.

Even before Granger, book owners often took it upon themselves to change a book by adding some “relevant” information to it: newspaper clippings, essays, photos, signatures or any other bit of ephemera that they deemed “went with” the book. Sometimes (rarely, if at all) the addition is accomplished beautifully and may actually be called an improvement, but more often it just ruins the book and turns it into a hodge-podge scrapbook.

There is a way to add a few pieces of thin ephemera to a book without adding bulk by using a blank page already extant in the book, paring the edges of the new ephemera to match a pared “loss” within the blank, then marrying the two together so there is no bump along the seam.

Contemporary a.k.a. period bindings

These book bindings are a sort of “facsimile” cover. “Contemporary” and “period” are words that refer to the approximate era when the book was originally bound rather than referring to the current era. Period bindings can technically be described as sophistications, but I think it is more helpful to be more exact with the terminology and always include the term period or contemporary with the description. It is not common for a bookbinder to try to match the original cover exactly. That would be attempting a facsimile. But it is possible to recreate binding styles from different periods and distress them so they look “right” or “old.” This technique is applied mostly to leather volumes from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries.

The reason this can be done is that there is a known progression of the creation of gold finishing tools from plain and sort of chunky to extremely delicate with lots of little dots and then into a sort of mix of the two. This is a gross overgeneralization, but what I want to point out is that you can sometimes estimate the age of a book from the kind of tooling that it has. You can also potentially tell the country that it came from or even who the bookbinder was in some instances. Bookbinders would have a set of tools made for them and frequently used the same ones over and over again.

In order to create a gold finishing pattern for a new contemporary binding, a modern day fine (a.k.a. “extra”) bookbinder will typically just use whatever tools they have on hand from that time period. They would have at least a small selection for each era. Just one of the brass hand tools needed for this process can cost $300 and having one made specially would cost even more. To recreate a cover as an exact replica would cost thousands just to have the right tools made. And then on top of that, the skill to do the gold finishing takes hundreds if not thousands of hours of practice so no amateur is going to be trying this. This just means that the number of contemporary bindings is relatively limited in the world and facsimile bindings are even fewer.

While there are some telltales that can help to distinguish a period binding from an authentically old binding, it can be really tough if the bookbinder didn’t use any modern methods or materials at all. And even then, new materials can be aged with just a little coloring or other techniques to distress them. When I was working for David Weinstein, he showed me many methods for aging a binding. Some of the things we did might seem a bit like “cheating,” but it was all about the aesthetics. He had created a mixture of watered-down inks that he called “Old Edge.” We would often use it to age threads for making end-bands. If we had to sand a text-block edge to remove a mark, we would age it back again with a swipe of “Old Edge.” He learned these techniques from his teachers at the London College of Printing. They add just the right look so that new bindings don’t jar the eye on a shelf full of originals. Bernard Middleton, the father of book restoration, is well known for smearing “dust” onto books to help age them.

Contemporary bindings can be impossible to spot as non-original because books were commonly re-bound as the means for reparation before the twentieth century. Just apply all your senses and pay attention to discrepancies. Is the quality of the binding too good to be true?

Spending time examining authentic books is the most useful thing you can do to educate yourself and get a feel for what looks right. But if you don’t live near an amazing library and can’t afford to spend the next three summers at Rare Book School in Virginia, there are a few things you can look for to help you determine the age of the book’s binding. Mind you these are not foolproof because there are always exceptions.

Blacklight: Modern materials that include brighteners such as new paper used for end-sheets or machine-made end-bands will fluoresce under blacklight and make the book suspect.

End-sheets:

- Acid Shadow: After one hundred years or so there will typically be some acid shadow (a color change and deterioration) going on where the paste-down covers the leather turn-ins. If the book you are examining has pristine paste-downs you may be looking at a new contemporary binding, but it could also be that the book just got new end-sheets and everything else is original.

- Grain direction: Check the end-sheet grain direction. It is possible that they were originally done with the grain the wrong way but it is something to consider. The grain is typically short which means that it bends more easily along the spine. If it is the wrong grain direction, the paper will curl against the rest of the book.

- Stains: If there are any stains on the first or last text-block pages, do these stains transfer properly from text-block to end-sheets?

Leather:

- Is it a little too pristine? Is there no wear and tear at all? Look at the inner hinges and outer joints.

- Some modern leathers are chemically altered — chrome tanned — to last longer but this makes them unable to “take” tooling very well. The tooling will not be crisp.

- Gold Tooling: If the bookbinder took a shortcut and used gold foil rather than gold leaf there will be less sparkle and the edges will not be crisp.

- Titling: The older the book, the more likely that the titling should be naturally crooked as each letter was hand tooled separately. Type-holders were invented around 1775 in England (1725 in Germany). These allowed lettering to be done in lines of words. Before the 1800s lettering was only done with one size. Labels were not a part of bookbinding until 1670. For more information read Bernard Middleton’s The Restoration of Leather Binding.

- Opening of the Boards: Another possible tell is to see if the boards open too far or not far enough. There is a certain feel to a book bound in-boards, and a cased-in book’s boards may open suspiciously easily or be oddly tight.

- Cord Lumps: One way to cut corners on a new binding is to “case it in” rather than bind it “in-boards.” Before case-binding, books were bound-in-boards. They were sewn on cords that were laced into the boards and then covered with leather. Even when the cords are recessed for sewing, the cords still make a little visible bump on the outer joint area (usually). It can be really subtle — and of course there are ways to add fake bumps to simulate these cord bumps — but if the outer joint is completely smooth you will want to check a few other points.

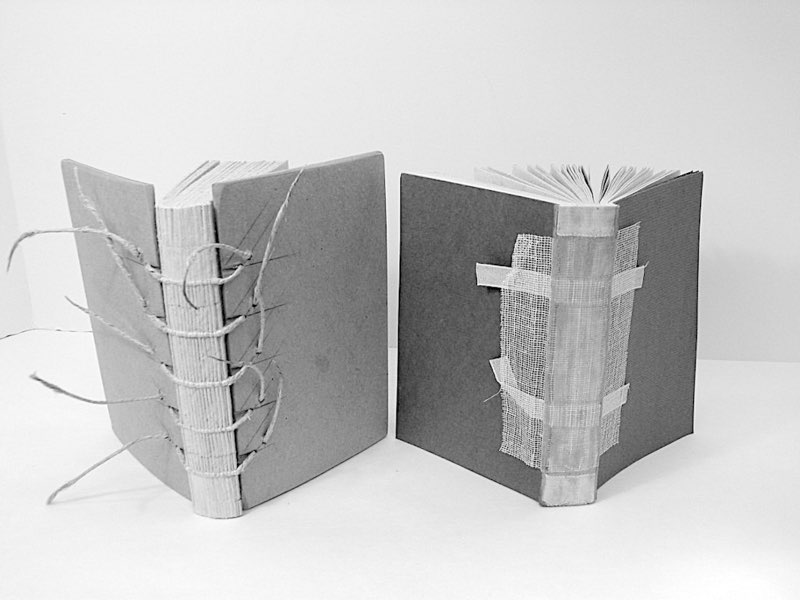

Bound-in-boards vs. case-bound in progress

Remboitage

Instead of creating a brand-new contemporary binding that looks old, some bookbinders are asked to re-use the cover from a less valuable contemporary book that is the same size (or nearly the same size) as their book that needs a new cover. This is called “remboitage” and it only rarely works really well on these older books. Typically, the spine is not salvageable for the new binding, and so only the boards can be used and a new spine must be created. This is as easy to spot as any other new spine so the illusion that it is an original binding is easily dispersed by looking at the turn-ins and other transition areas. If it is a half binding the spine may be new but the corners might be the older leather and the color match may not be perfect. I have seen cases where it is not even the same animal skin: calf instead of goat or sheep.

Remboitage is more successfully camouflaged on modern bindings and it is much harder to tell it has been done. Intent must come under scrutiny in these cases because these books are not as scarce so what is the reason for the new cover? In fact, all you can really look for are indications that there is a new mull lining under the paste-down. Check to see if that area has become oddly lumpy. Re-casing must include a new layer of mull because you have to cut the original mull to remove the text-block. Thus, the mull that is “visible” under the paste-down will either be doubled, because the original was not removed, or the original will be removed, which can cause some uneven thinning to the paper.

You may think that you would also see a new hinge or endpapers, but it is possible to keep the endpapers intact in the re-casing. It is super hard to do without odd wrinkles or the flyleaf being crooked to the text-block, but I know it can be done because I have done it. Unfortunately, all the telltale signs of modern remboitage are also the signs of simply re-casing the book if it had broken hinges. Big sigh.

A “Legacy” Sophistication

Sophistication has a bad rap in the book collecting world, but for some, it can be a cheap solution to a common problem. Here is an example of a time it benefitted a client of mine. This client brought in a pile of Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar books. Some pages were torn and scribbled on and some had been “repaired” with tape over the spines. Her goal was to have them restored to full functionality as well as have them look and feel as original as possible for her grandchildren. I think of these as legacy restorations. She had some money to spend on the project but since there were several books, the amount she had budgeted wasn’t going to stretch very far per book.

The first thing I did for the client was to look up the availability of the same books in better condition. I discovered that, for about twenty dollars each, she could replace her books all together. Great, right? However, she was truly attached to these books as physical objects. Those were her scribbles from when she was little! She really wanted these books and not new ones. But the books were in such bad shape that it would be impossible to restore them properly on her budget, so we came up with a compromise. We decided to buy some of the books (same editions) in better condition in order to use them for “parts” for her own books. I wound up replacing the covers of the books that had the spines taped because it was not possible to remove the tape without destroying the image underneath it. By doing so I kept her personal scribbles on the pages intact. I also replaced several of the un-scribbled torn pages.

Her goal was to create the same wonderful experience of the Babar books for her grandchildren that she had grown up with and for the books to continue in her family. Sophisticating the books was a very economical way to get the best result. If she had been a book collector, we would have gone a completely different route. If she had been a book dealer, I never would have seen those books. Book dealers just don’t buy books that are damaged like these were unless they are extremely rare and valuable.

Fraud

The most common book fraud is perpetrated by removing identifying factors. That’s because it is the easiest to do. With a little scraping you (well, hopefully, not you personally) can remove letters, words or numbers to change the demarcation of an edition. This is exactly what happened in one of the few cases of actual fraud I have seen.

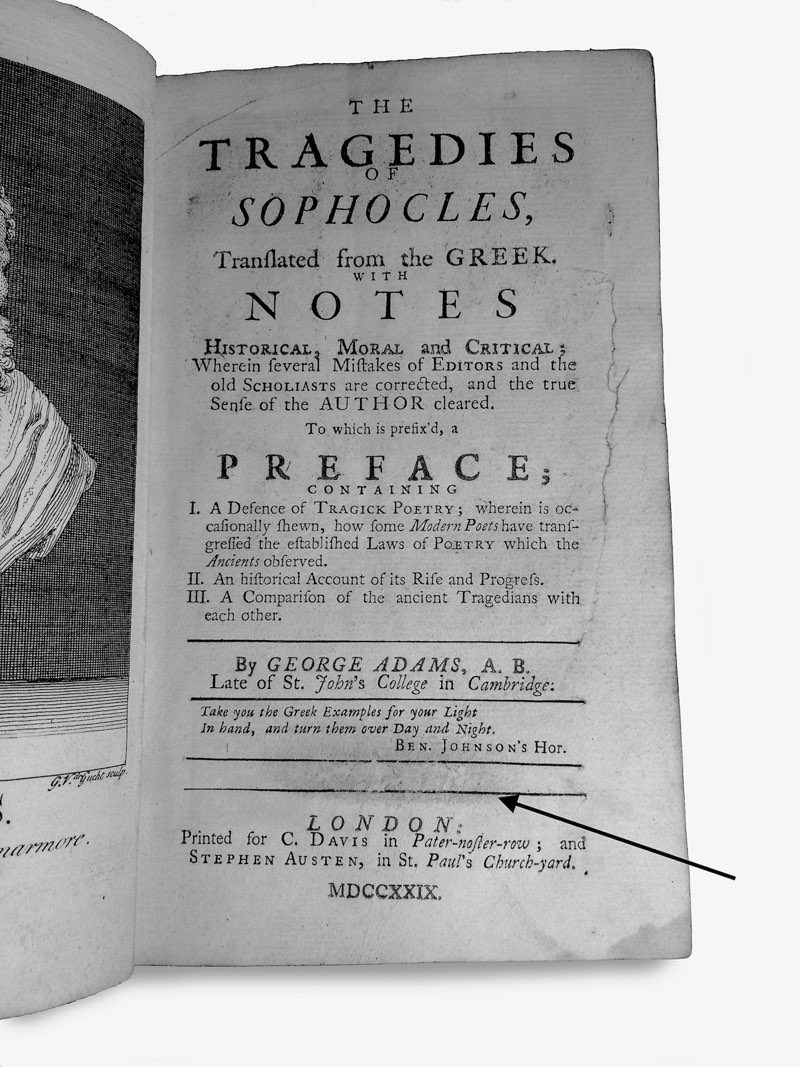

Removing Volume or Edition Indicators

The book was a copy of Sophocles that a client bought thinking it was a complete book unto itself, only to be disappointed when I pointed out that someone had “erased” the words “Volume One” on the title page. Sadly, I didn’t notice it until I had already restored the book. This is a great reminder to always do your own collation before sending a book out for restoration. Collation just means to go through each page and make sure that they are all present and accounted for and in the correct order. This also gives you a chance to note any tears or stains that need attention or that might indicate fraudulent alterations.

Pay special attention to the copyright page. Get out a magnifying glass and examine it carefully. Hold the page up to the light. Feel it with your fingers. You have learned what to look for now so don’t be fooled.

Sophocles fraud

Swapping Out or Marrying

Another act that is definitely fraudulent is swapping or “marrying” different pieces of books from different editions. Swapping should only be done between the exact same editions and purists will tell you flat out that it is never acceptable to swap at all. You will have to decide for yourself what is right.

Fraud is not the same as forgery. You can create a forgery of a book but it is only fraud if you try to deceive someone and profit from it. You can even collect forged books legitimately. Whole book forgery is rare. The work is just not worth the reward to forge entire books. Forgers would rather take the easy road and recreate single sheet items such as the famous Oath of a Freeman. Really lazy forgers will just copy signatures.

I can only think of a few spectacular examples of high-end book forgery and they have already been written about thoroughly. I highly recommend reading about Marino Massimo De Caro’s exploits where he actually forged a book by Galileo and nearly got away with it. Saucily, the forger quotes Borges’ Ficciones saying, “When a book is false, it is equal to, if not better than, the original.” I think all forgers must have this sort of inflated ego. A few other books that cover book crimes are Bartlett’s The Man Who Loved Books Too Much, McDade’s Thieves of Book Row, and Basbanes’ A Gentle Madness. All about true stories.

While I can point out examples of a few book forgeries in the world, there simply are not very many book forgers out there. Even just creating honest replicas is a lot of work. In fact, it was too much work for Michael Chrisman. In December of 2016, Chrisman, an American bookbinder, was convicted of another kind of fraud. He promised the completion of traditionally bound, replica Gutenberg Bibles, and while he did complete five of the seventy Bibles, he collected fees as though more were completed to the tune of $480,000. The clients must be so disappointed to not get their books.

Because I remember first learning about book fraud from my former teacher, David Weinstein,11 I decided to ask him to share some stories about his own encounters with it. David studied traditional bookbinding, restoration, and related subjects at the London College of Printing (now called the London College of Communication). He graduated in 1982 at the top of his class and started running the Heritage Bindery for his uncles, Ben and Lou Weinstein. He is still restoring books near The Iliad, his brother’s well-known bookshop in Los Angeles. Here is what he had to say.

INTERVIEW WITH DAVID WEINSTEIN, EXPERT BOOK RESTORER AND BOOKBINDER

Sophia: Tell me about your experience restoring books.

David: I have lots of stories about books, booksellers and bookbinding. This has been my life for better or for worse. Back in 2000, I attended the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) convention. Bernard Middleton’s lecture on facsimile printing12 was delivered by Mirjam Foot and afterwards Bernard stood up to answer questions. I remember that his jacket was buttoned crooked. I took the opportunity to ask what he saw as the difference between a facsimile and a forgery. Bernard quickly and clearly responded with only one word — “intent.”

Sophia: What do you think? Can people recognize your restoration work? Is that a problem?

David: It has never been my intent to fool my clients. I am given damaged books, and with all my clients, invisible restoration is ideal. The exception is when it is for university special collections as they pay for conservation not restoration. It’s not for resale, so invisibility isn’t necessary or even desired as they want a clear record of what was done.

Sophia: Do you know any stories about actual fraud?

David: As I understand it, a reputable dealer is required to describe the defects and subsequent repairs but sometimes their cataloguer might not have noticed the restoration. Then if the sale is disputed and the dealer refunds the customer, the dealer is required to describe this dispute to the new prospective buyer. Here is a good example of how this can work out. In the mid 1970s, Heritage sold a Shakespeare first edition to a client (for $175,000 as I recall). Later it was x-rayed and the portrait and/or title was deemed an early hand-drawn facsimile. Heritage was not at fault (they didn’t have the facsimile made) but they were responsible. (See the ABAA Code of Ethics. I think Lou Weinstein, president of Heritage, wrote them.) The client wanted his money back. Heritage asked for a small delay to pay the gentleman his money and meanwhile found another client to purchase the defective book (with full disclosure) for the same price. Everyone was happy.

Sophia: That’s a great story. Can you think of any other examples?

David: On one occasion I was asked to work on a Shakespeare Third Folio 1664. Supposedly it had additional Shakespeare material with it. The binding was scorched all around (probably because unsold copies were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666) and all that was left of the leather was a lozenge-shaped piece on the front board. Forty percent of the board was gone, so I re-bound the book in full reverse calf with old endpapers and then I bumped and distressed the covers. Then I took that remaining bit of leather from the original and mixed it into a paste and spread it all over the new work to preserve that small bit of history. I recall the customer being well satisfied. It sold quickly. I don’t recall seeing the description of it being published but I do wonder if they claimed it was the original leather.

One more thought: the word sophisticated sounds like something desirable, but it isn’t desirable in the collecting world. And yet I have been asked to sophisticate books many times. Bookbinders do have ethics about these things though, and some of us will refuse to alter books if we are suspicious of the intent. I know one bookbinder that was fired by the bookseller shortly after he wouldn’t trim down an uncut Shakespeare folio title page to tip into a shorter copy. (No, I didn’t do it either.) Did the bookseller eventually find someone to do it? If he did, did he accurately describe it? Just one more example of why the phrase ‘buyer beware!’ exists.

David’s experiences of fraud mirror my own. Being asked to do repairs that seem questionable definitely happens in this business and we are often left wondering if our work is properly described later. Someone once actually asked me to change the publisher name on the spine. (Which I declined to do.)