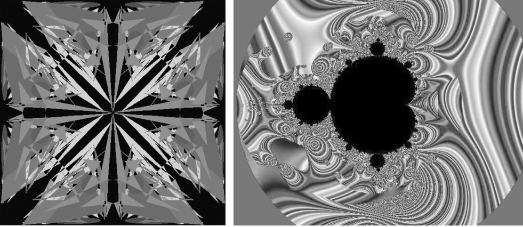

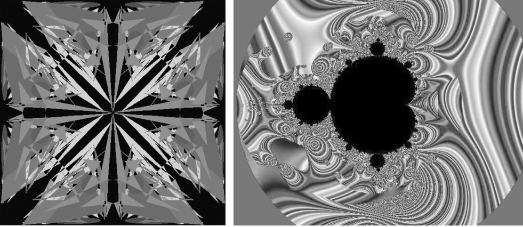

FIGURE 6.1 Kaleidoscopic image (left panel, a linear object) vs. the Mandelbrot fractal set (right panel, a nonlinear object). Which is more complex?

CHAPTER 6

CLINICAL QUERIES: ASKING THE 31/2 KEY QUESTIONS

It is better to know some of the questions than all of the answers.

—JAMES THURBER (1894–1961)

We live in a “bottom-line” culture. The need for multitasking during rounds creates additional pressures to “get to the point.” The more urgent the situation, the greater the pressures are to fast-track to those action points. At the same time, clinical decision making is replete with ambiguities, false starts, false positives, and false negatives. Life and trying to keep people alive are complex enterprises. The way we frame questions, just as the way we frame images, is often a key to what we see or don’t see.

Clinicians resemble major league baseball hitters, who face a daunting array of tough pitchers (our patients) who throw a lot of curveballs and change-ups. But unlike major leaguers, who can win batting titles by not getting a hit in two of three chances (i.e., batting “.333”), clinicians must try to bat “1.000” Like good hitters, experienced clinicians learn to “look for pitches” and to think primarily about one or two main possibilities when they hear about a case. Developing an anticipatory intuition or framework is essential in clinical medicine. A related part of clinical diagnostic skills is the ability to assess a situation and make correct diagnoses within seconds or minutes of hearing or seeing a case. The ability to size things up is especially important in acute settings such as the emergency department, intensive and critical care situations, and in surgical and other procedure suites.

This type of intuitive sensibility is related to the well-known phenomenon of the validity of first impressions. Author Malcolm Gladwell describes and celebrates this phenomenon of intuition in his provocative 2005 book, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. As Gladwell notes: “There can be as much value in the blink of an eye as in months of rational analysis.”

Leaps of intuition are not magical, but they are still neurophysiologically mysterious. Perhaps these “aha” moments have to do with the brain’s nonlinear capacity to integrate past experience and process multiple cues and clues. Test takers, including those grappling with the Medical College Admission Test, medical boards, and certification maintenance examinations, often apply this principle, which is the basis of the adage “When in doubt, go with your first impression.”

In the contemporary language of complex systems, an intuitive insight is an example of an emergent process in which the entire thought or insight cannot be reduced to a simple addition of its components. Intuitions are the “eureka moments” of life and an essential feature not only of our daily, creative functioning but also of clinical reasoning. In this respect, creative intuition is not at all like a kaleidoscopic image, where the pieces all add up to the final design. Instead, emergent ideas are more like the nonlinear creation of the Mandelbrot set, a fractal object that seems to explode from a deceptively simple recipe (Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 Kaleidoscopic image (left panel, a linear object) vs. the Mandelbrot fractal set (right panel, a nonlinear object). Which is more complex?

Yet intuitions can also be wildly off base, to use another baseball metaphor, and constitute only one component of clinical assessment, which must be carefully validated and tested. Thus, a key skill to develop so as not to miss diagnoses is the complementary and essential ability to consider all of the other possibilities when thinking about diagnosis, etiology, and therapy. Sometimes our first impressions—the blinks—are dreadfully wrong or, at the very best or least, incomplete.

Dr. Jerome Groopman at Harvard Medical School has written eloquently about this competing challenge between intuition and reflection in his book How Doctors Think. As noted by Dr. Groopman: “Doctors must be wary of ‘going with your gut’ when what’s in your gut is a strong emotion about a patient, even a positive one. This species of ‘affective bias’ can skew a physician’s judgment and lead to misdiagnoses.”

Another mechanism of misdiagnosis has been called confirmation bias or anchoring. As Dr. Groopman explains: “Anchoring is a shortcut in thinking where a person doesn’t consider multiple possibilities but quickly and firmly latches on to a single one, sure that he has thrown his anchor down just where he needs to be.” Clinicians therefore need to cultivate an approach that incorporates simultaneously two tendencies that are seemingly at odds with each other: intuition and systematic thinking. This competition could be referred to as the glimpse vs. the gaze.

In actuality, this either–or distinction is itself an oversimplification. In addition to quick and longer looks, clinicians need to cultivate a third modality of seeing: the re-look—the self-imposed intellectual discipline to revisit first, second, and even third impressions and to be open to the “possibility of other possibilities.” In medicine, these other possibilities include diagnoses not yet considered and, in rare but path-breaking cases, new syndromes and diseases that remain to be discovered, or novel presentations of known pathologies.

Keep in mind that not too long ago the first recognized cases of HIV/AIDS, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and the Brugada syndrome were reported. One of the most exciting facets of clinical medicine is that the next patient you admit to your service or see in the clinic might fall into the latter group of about-to-be-recognized diseases or reportable presentations. Most exciting is that such discoveries are as open to medical students as they are to seasoned clinicians.

Finally, as noted by Dr. Groopman:

A technique to foster this type of critical thinking is for clinicians to develop a routine, much like they prescribe for exercise protocols. The idea of a routine here is not intended to foster a reflexive type of predictability. Rather, it is intended to encourage “out of the box” thinking by opening up the number of options being considered, and by encouraging the search for alternative explanations.

From a practical point of view, how can you combine the glimpse and the gaze: to be both intuitive and expeditious but also thoughtful and comprehensive? Obviously, there is no single “mechanism” to achieve this aim. But for most situations in clinical medicine, especially involving diagnostic considerations, and applicable when looking at clinical data sets (e.g., lab test results) or physiologic recording studies (e.g., ECG), it is worth asking the 31/2 key questions:

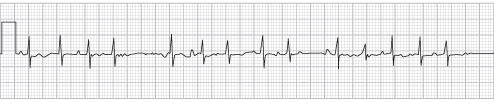

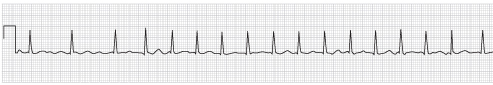

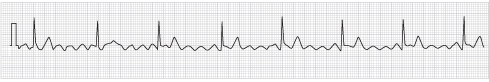

To illustrate this approach, let’s begin with an example from ECG analysis (Figures 6.2 to 6.4). Beyond its utility as a vital clinical skill, ECG interpretation is important because it exemplifies and reinforces the universal clinical needs to be both systematic and thorough. Consider the ECG of a patient with palpitations shown in Figure 6.2. The lead II rhythm strip shows a rapid irregular rhythm with a narrow QRS complex. If you describe this over the phone to a colleague or look at it in the usual clinical haste, atrial fibrillation will probably be the initial “blink” impression, leading to anticoagulation, antiarrhythmic therapy, and possible consideration of electrical) cardioversion.

FIGURE 6.2 An irregular rhythm. Compare and contrast with Figure 6.3.

FIGURE 6.3 Your patient’s ECG (lead II) shows an irregular rhythm. What is the diagnosis? What is the differential diagnosis?

FIGURE 6.4 This rhythm strip resembles atrial fibrillation but is actually due to something else.

Taking a step back and looking at the differential diagnosis (DDx) of a rapid and irregular narrow complex (normal QRS duration) rhythm is a useful exercise. The DDx includes not only atrial fibrillation but four other major possibilities:

A closer look at the rhythm strip in question reveals that it is actually MAT, a rhythm that simulates atrial fibrillation but has quite distinct etiological implications and management. MAT is defined by the appearance of three or more consecutive nonsinus P waves at a rapid rate. The most common substrates are chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), usually with an acute or subacute exacerbation, or severe organic heart disease. The management of MAT in COPD entails therapy of the underlying pulmonary process and sometimes use of calcium channel blockers such as diltiazem for rate control. However, in contrast to atrial fibrillation, MAT is not an indication for anticoagulation (unless it leads to or is associated with atrial fibrillation). Further, electrical cardioversion for MAT will be ineffective and potentially hazardous. For contrast and comparison, an example of actual atrial fibrillation is shown in Figure 6.3.

For additional comparison, the third ECG case (Figure 6.4) indicates the complications in differential diagnosis introduced by artifact—spurious findings that simulate medical diagnoses and that often lead clinicians astray. In this case, artifact gives the appearance of atrial flutter or fibrillation in a patient with coronary artery disease who is actually in sinus rhythm.

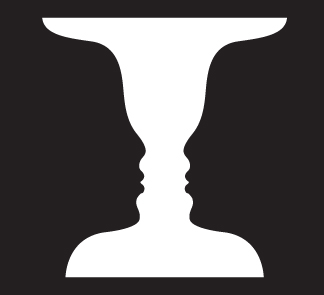

These examples illustrate the problems of relying on the blink reflex to make clinical assessments. The pitfalls of overreliance on initial intuitions are also illustrated by an example (Figure 6.5) from a setting that would appear to have no relation to clinical medicine. This black-and-white drawing is an optical illusion that you have probably seen—but not in medical school. It is sometimes called the Rubin Vase after the Dutch psychologist Edgar Rubin, who made these images famous.

FIGURE 6.5 What do you see in this simple-appearing black-and-white image?

Take a quick look (blink or glimpse). What do you see? A vase (white central area) or two faces (black side areas)? Different observers have different first impressions. But with further attention (gazing), the flickering of this picture between the two images is apparent. Furthermore, what we first see may be biased by what we are told to look for: one vase or two faces. This type of expectational bias as a source of medical errors is discussed further in Chapter 7.

This illusion is also medically relevant (in case you were still puzzled) because it illustrates the clinical principle that a single impression may at best be only partly insightful or explanatory. Further scrutiny yields additional information and raises additional questions. The illusion illustrates symbolically that in medicine, as in art, more than one meaning or diagnosis may be at play simultaneously. Patients not infrequently present with two or more concomitant conditions, which may or may not be directly related.

Sometimes, identifying one explanatory diagnosis may mask another or inhibit the search for even more alternatives—the “case is solved” syndrome of anchoring. In the example above, the diagnosis of Conn’s syndrome seemed to nail down the cause of the patient’s fatigue. However, another diagnosis, chronic granulocytic leukemia, was lurking in the background. Understandably, there is the human reaction that “one explanatory diagnosis is enough, so let’s not go looking for trouble.”

Dual or multiple diagnoses have major implications only if the conditions are treatable. In the latter category would be a patient presenting with heart failure and known hypertension and coronary artery disease who has developed critical aortic stenosis, a surgically remediable lesion. Not asking “What else could be causing the heart failure—beyond hypertension and coronary disease?” would have profound implications for aortic valve replacement, a potentially life-saving intervention.

Learning and practicing critical thinking skills that resist conventional wisdom, actively looking for anomalous findings, and harnessing the energies of imagination are powerful antidotes to cognitive errors (Chapter 7). From a more positive perspective, critical and imaginative thinking are the sources of successful therapeutic interventions and clinical discoveries. As noted above, perhaps one of the patients you are seeing now has a new syndrome yet to be recognized. Helping trainees acquire and master these skills that join the systematic with the imaginative is one of the most challenging educational goals in medicine, particularly in this age of distracting info-glut (see the Introduction).

These practical questions are intended to provide an orienting space to explore clinical possibilities, with particular emphasis on always asking “What else could it be?” as a cognitive reflex and of considering the widest range of therapeutic options. However, trainees and their mentors should be mindful that the very act of posing essential queries may squeeze out other important questions that then remain unasked. For example, a major limitation of the Dx/Rx–Cause(s)–Therapeutic Options paradigm is that it does not explicitly address mechanisms of disease, the deeper understanding of the physiological and pathophysiological processes that underlie diagnostic considerations. Getting at these deeper issues is metaphorically like peeling back the next layer of the onion, which in the parlance of critical thinking is sometimes termed the transition from information and knowledge to understanding.

In the case presented above of MAT vs. atrial fibrillation, this deeper probing leads to the frontiers of clinical cardiac electrophysiology. The mechanisms of these arrhythmias are only incompletely understood and involve discussion of highly technical concepts, including abnormal automaticity in the pulmonary vein areas of the left atrium and reentry. How far attendings want to go in discussing the current understanding of relevant disease mechanisms depends on their expertise and time constraints. Gathering a group of challenging cases to present to an invited colleague with “hands-on” experience is one way to make sure that these fundamental issues get discussed, even on very busy services. Finally, recall that even the most elegant of mechanistic explanations are likely to be incomplete and perhaps fundamentally incorrect. For example, our understandings of mechanisms of both MAT and atrial fibrillation continue to evolve, despite decades of study.

One of the most revolutionary examples of mechanistic reappraisals comes from gastroenterology. The pathophysiological link between the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and most peptic ulcers was not recognized until the 1980s, through the initially controversial work of two Australian physicians, Dr. Barry Marshall and Dr. Robin Warren. Their discovery, overturning decades of conventional wisdom and medical/surgical dogma about the noninfectious hydrochloric acid–related mechanism of ulcer disease was recognized with the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Perhaps the commonly posed attending’s round question “What is the underlying mechanism?” should be replaced with “What is our current understanding of the putative mechanisms, and what are the cutting-edge areas of debate and research?”