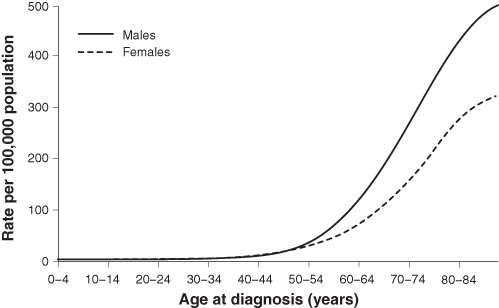

FIGURE 12.1 The rising prevalence of colorectal cancer with advancing age.

Adapted from Ballinger AB, Anghiansah C. BMJ. 2007;335:715–718. Reproduced with permission.

CHAPTER 12

WHAT IS DISEASE? WHAT IS HEALTH?

Doctors are men who prescribe medicines of which they know little, to cure diseases of which they know less, in human beings of whom they know nothing.

—VOLTAIRE (1694–1778)

To study the phenomenon of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.

—SIR WILLIAM OSLER (1849–1919)

If you want to win a friendly wager, turn to a fellow student or house officer (or if you have sufficient courage, to one of your attendings), and bet that they cannot readily answer two basic questions: “What is disease?” and “What is health?” Attendings can pose the same query to their students, residents, fellows (especially those who might be a bit overconfident), or even colleagues.

Next, if you want to up the ante, ask your colleague not only to define the term disease but to distinguish it from syndrome. Are the two terms identical? Or is a syndrome one class of disease processes? Further, in what respect is the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion related semantically to the posttraumatic stress disorder syndrome?

Consulting the world’s leading textbooks of medicine for help with these definitions is problematic—no definitions are given. Neither the contributors to this book nor any of the colleagues we polled can recall any course in medical school where the definitions of disease or disease syndromes, the very basis of our profession, were discussed explicitly.

One obvious problem with the first of these two definitions is that some diseases do not actually impair functioning until a more advanced stage or some threshold is crossed. For example, coronary artery disease is often completely asymptomatic and may produce no evidence of physiological impairment until the person presents with a heart attack or sudden cardiac arrest, possibly resulting in death. In such cases, a person with a clearly demonstrable disease process (in this case, by autopsy evidence) may not even have time to develop sustained symptoms (i.e., chest pressure, shortness of breath, palpitations, etc.), let alone become a patient.

The usual definition of disease also relies on impairment of what is called “normal functioning,” creating an endless-loop circularity in which disease is the absence of health and health the absence of disease. An even more subtle problem with the standard definition is illustrated by the following question: Is localized, low-grade in situ cancer of the prostate detected at postmortem examination in an 80-year-old man who dies of a massive stroke a disease, or is it just an incidental finding (see Chapter 3)?

Dr. Judah Folkman and Dr. Raghu Kalluri of Harvard Medical School, in a 2004 article in Nature, reviewed data related to a striking observation:

Many of us may have tiny tumours without knowing it. In fact, autopsies of individuals who died of trauma often reveal microscopic colonies of cancer cells, also known as in situ tumours. It has been estimated that more than one-third of women aged 40 to 50, who did not have cancer-related disease in their life-time, were found at autopsy with in situ tumours in their breast. But breast cancer is diagnosed in only 1% of women in this age range. Similar observations are also reported for prostate cancer in men. Virtually all autopsied individuals aged 50 to 70 have in situ carcinomas in their thyroid gland, whereas only 0.1% of individuals in this age group are diagnosed with thyroid cancer during this period of their life.

In this context, more questions arise: Do such ubiquitous in situ cancers, discovered as “incidental” findings at autopsy, or in biopsy or imaging studies while we are still alive, qualify as diseases? If so, should they be treated? How much harm is done unintentionally by treating abnormalities, even cancers that will have no prognostic impact? On the other hand, how much harm is done by missing subtle, preclinical conditions that fly under the radar of conventional screening?

Along a similar line of inquiry, one might ask: Is “physiological aging” a disease? Getting old is, after all, associated with loss of normal, or at least optimal, functioning of multiple organ systems (creatinine clearance, memory, golf putting ability, etc.) and is the source of innumerable complaints (especially about the latter two deficits).* Yet physiological (sometimes termed successful or healthy) aging is not considered a disease per se, although many diseases increase markedly in frequency with aging (Figure 12.1). Furthermore, the clinical term premature aging implies that aging itself is a pathological or at least a prepathological state.

FIGURE 12.1 The rising prevalence of colorectal cancer with advancing age.

Adapted from Ballinger AB, Anghiansah C. BMJ. 2007;335:715–718. Reproduced with permission.

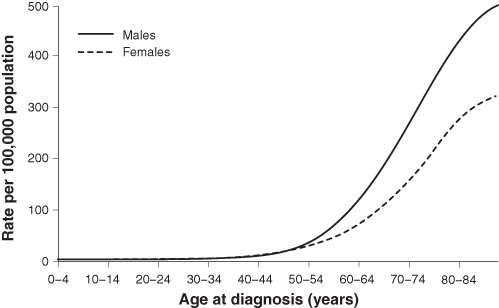

An emerging area of geriatrics focuses on the frailty syndrome, a very common type of pathological aging characterized by a constellation, including weakness, fatigue, weight loss, decreased balance, reduced physical activity, slowed motor processing and performance, social withdrawal, cognitive impairment, and increased vulnerability to stressors. The frailty syndrome (Figure 12.2) is of interest because of its increasing prevalence in the United States and other postindustrial countries, and because it is not a specific disease. Instead, frailty includes markers suggesting a multisystem process that is important because it indicates a statistically significant increase in risk of falls, dementia, heart disease, serious infections, and so on. The approach to the diagnosis and treatment of frailty is challenging contemporary notions of “static biomarkers” (single tests) and also of therapeutic “targets” (magic bullets, discussed in Chapter 10). An important consequence of the concept of frailty as a breakdown of integrative function is that its treatment is likely to require multimodal approaches (e.g., exercise, social interactions, osteopenia therapy) rather than a single magic bullet.

FIGURE 12.2 Frailty is the result of a syndromic set of dynamical processes.

From Fried LP et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001; 56: M146–M156. Reproduced with permission.

The dictionary definitions of disease and syndrome given earlier also fail to distinguish clearly between primary diseases and injuries. A Colles fracture (of the distal radius) impairs functioning and has distinguishing signs and symptoms, but clinicians do not usually consider a bone fracture due to falling off a bicycle or tripping on a niece’s rollerblades a disease process. However, if the fracture is associated with some underlying bone impairment, such as osteoporosis, metastatic cancer, multiple myeloma, or osteogenesis imperfecta, the notion of a disease process becomes more relevant and the term pathologic fracture is applied. Or, if the precipitating event is a fall due to a syncopal attack from a cardiac arrhythmia or from a seizure, the injury also becomes part of a disease process. Trauma, itself, may also induce a cascade of pathophysiological events involving activation of inflammatory and coagulative systems that may lead to severe sepsis with multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, an all-too-common downward spiral associated with exorbitant mortality in intensive care units.

An important and increasingly recognized link between stress and illness occurs in people, especially family members, who have major responsibility for taking care of others with a chronic illness. The physical and emotional stressors have been associated with major adverse medical consequences, including severe clinical depression, immune dysfunction, premature aging, cardiac disease, and even increased mortality. The term caregiver syndrome is used widely now to describe what Dr. Jean Posner, a neuropsychiatrist, has defined as “a debilitating condition brought on by unrelieved, constant caring for a person with a chronic illness or dementia.”

The causes of this syndrome challenge conventional notions of mechanisms and are probably multifactorial, including induction or augmentation of neuroautonomic and biochemical alterations that promote a proinflammatory, procoagulative state. The degree to which difficult-to-quantify factors such as physical stress, sleep deprivation, anxiety and guilt, social isolation, and economic hardship play a role is speculative and may vary from one caregiver to another. By its very nature, this syndrome also challenges our target-based, “pharmacocentric” approaches to disease management (Chapter 9). At the very least, clinicians should query patients and their family members about aspects of caregiving roles.

For a dramatic example of the putative link between stress and pathology, consider this observational case study. A major earthquake struck the Los Angeles Northridge area at 4:31 a.m. on January 17, 1994. This geological event was one of the strongest ever recorded in a major North American metropolis. The earthquake provided a unique opportunity to study the immediate relationship between emotional stress and sudden cardiac death and all-cause mortality. Dr. Jonathan Leor and colleagues at the Good Samaritan Hospital of the University of Southern California reported that the day of the earthquake coincided with a sharp and highly significant (about fivefold) increase in the number of sudden deaths from cardiac causes, spiking from a daily average of 4.6 ± 2.1 in the preceding week to 24 on the day of the earthquake.

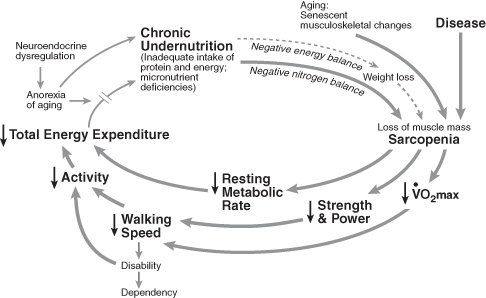

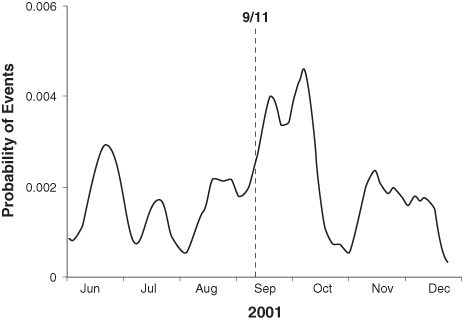

Similarly, a significant increase in life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias was reported in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in the New York City area in the month following the Al Qaeda terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001 (see Figure 12.3). What are possible mechanistic connections between stress and sudden death, or stress and the appearance or progression of other disease processes?

FIGURE 12.3 The day-to-day incidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmia triggering implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy during an eight-month observation period. Note the substantial spike in event rate in the 30-day period after September 11, 2001.

From Steinberg JS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1261–1264. Reproduced with permission.

The provocative and still controversial fetal origins of disease hypothesis stretches our notion of disease still further. The premise is that susceptibility to adulthood cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus may be “programmed” in utero in response to fetal undernutrition. This theory is sometimes referred to as the thrifty phenotype hypothesis.

The examples of pathologies noted above, both proven and provocative, uncover limitations in clarifying the definition of disease and suggest the need for other strategies. One reasonable approach to reconsidering what constitutes a disease would be to define it by what it is not: the absence of healthy function in one or more organs or in the system as a whole. However, this strategy also leads to immediate complications. The same textbooks that lack any definition of disease or pathological syndromes also do not offer even a single paragraph, much less a chapter, describing what health is! As stated earlier, one soon becomes knotted in an endless loop in which disease is defined by the absence of health and health by the absence of disease. The standard textbooks do, of course, provide extensive tables with normal limits and ranges for a wide variety of laboratory tests and physiological variables. But tabulated numbers are of very limited value in the overall definition of health.

Health is one of the most difficult and perhaps most controversial medical concepts to define. To answer this question is not just to engage in a distracting philosophical debate. The entire enterprise of medicine is devoted to curing disease and to restoring and maintaining health. The reflex response that health is simply the absence of disease is neither rigorous nor intuitively satisfying. Defining health by negation, essentially saying that you are “nondiseased,” is like calling life the state of being “un-dead.” What are the ingredients of health or, even better, of healthy function?

More than the absence of disease, health is an active dynamical state* that implies not just physiological functioning of component organs and of the overall organism, but also the integrated ability to cope with a very wide range of often unpredictable intrinsic and extrinsic physical and psychological stresses. Healthy systems interact both within and without in creative and adaptive ways. In a sense, the healthiest systems are the most supple and resilient. The capacity of a system to cope (its copability) is closely related to the reserve of the system (its capability).

The purpose of this section is not to provide a perfect definition of disease, of disease syndromes, or of health. Consensus on these issues is not likely. The standard dictionary definitions given above, although flawed, are certainly reasonable starting points for discussion, deconstruction, and debate. Most generally, we raise the questions above because they illustrate how ambiguous even the most apparently secure descriptions in medicine are: that is, health vs. disease. As discussed in the Introduction and Chapter 7, ambiguity is a fundamental aspect of medicine and a major motivation for and limitation of evidence-based medicine.

Importantly, students of medicine should not grow too reliant on contemporary diagnostic categories, proposed mechanisms of disease, and tests currently available. These key, taken-for-granted elements of the clinical world are all likely to be upgraded, amended, or completely replaced over the years, in some cases beginning tomorrow or even yesterday. More specifically, we do propose two practical suggestions for clinicians.

In fact, the CAD process usually starts years before an unstable coronary syndrome occurs (acute myocardial infarction, new onset or progressive angina, or even sudden death) and includes a progression of atherogenic stages culminating in a ruptured coronary plaque. The process probably began decades before the presenting problem, in early adolescence or even in childhood in industrialized countries, with the onset of subtle damage (especially due to excess lipids and increased blood pressure) to the coronary artery endothelium. Indeed, Dr. William Aird of Harvard Medical School and his colleagues have proposed that the endothelium itself may constitute a neglected organ system rather than simply comprising a cellular “pavement.”

Referring to such pathologies as disease processes rather than as point-like events also encourages clinicians to include in their pathogenetic discussions important and sometimes modifiable risk factors and contributors that otherwise get marginalized. In the case of CAD, potentially modifiable risk factors include diet, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemias, job stress, and depression.

For community-acquired pneumonia, the risk factors (only some potentially modifiable) include age (the very young or elderly), influenza or other viral syndromes, exposure to infectious agents (e.g., Legionnaire’s disease), chronic underlying conditions such as Parkinson’s disease or the frailty syndrome, chronic bronchitis, immune dysfunction associated with stress or steroid use, and others.

Contrary to common clinical parlance, heart failure is a syndrome and not a disease. Patients typically share common symptoms (fluid retention, dyspnea, fatigue, and exercise limitation) and signs (e.g., resting sinus tachycardia, S3 gallop, basilar lung rales, pedal edema). Their perturbed physiology is marked by a relative decrease in cardiac output, inadequate to meet systemic demands despite normal or increased cardiac filling (diastolic) pressures. However, signing patients in or out of the hospital with just the diagnosis of heart failure is akin to assigning them the diagnosis of “fever.”

The obvious follow-up question with the latter diagnosis is, “Fever due to what cause?” If the cause is undetermined and the fever is present for a sufficiently long time, the diagnosis becomes fever of unknown origin (FUO).* Surprisingly, clinicians who would consider a diagnosis of fever to be completely inadequate will use the term heart failure without requiring a statement about the likely etiology.

Furthermore, distinct from a specific disease, the heart failure syndrome subtends low output and high output pathophysiologial subvariants, as well as systolic and diastolic subsets, and may itself be the end stage of many specific processes, ranging from CAD, to systemic (essential) hypertension, to cardiomyopathy and valve disease, or often to some combination of these pathologies.

In contrast, application of the term disease implies a more consistent set of pathophysiological derangements. For example, hypertensive heart disease is treated as a relatively specific entity that may itself lead to the heart failure syndrome.

Even the seemingly “pure” causal example of hypertensive cardiovascular disease leading to heart failure syndrome is not as neat as clinical summaries and some textbooks might suggest. Systemic hypertension is itself a syndrome more than a disease. The most common variant, essential hypertension, is idiopathic and often multifactorial. Renal disease, the other most important cause of systemic hypertension, may be due to renovascular diseases (fibromuscular dysplasia or atherosclerotic disease) or various renal parenchymal diseases.

What about other apparently well-characterized syndromes? Hyponatremia-related syndromes all share one common and obvious feature, a reduction in serum sodium ion concentration. This laboratory abnormality (after “correcting” for the degree of hyperglycemia and after excluding spurious causes due to hyperlipidemia, etc.) may in turn be associated with three volemic states: euvolemic, hypervolemic (edematous), and hypovolemic.

However, a major “cause” of the first category of euvolemic hyponatremia is inappropriate ADH secretion, which is a syndrome and not a disease. Furthermore, the different causes of hyponatremia are fundamentally unrelated, such as those associated with heart failure or Addison’s disease. Therefore, is hyponatremia really a syndrome or is it a lab abnormality in search of syndromic attachments? Can there be syndromes within syndromes? The closer we get to many syndromes, the less they behave like a group of concomitant signs or symptoms that characterize a particular abnormality or condition.

Medical advances also indicate that many conditions that we previously considered to be discrete or monolithic diseases are actually more nonspecific syndromes, with multiple causes and substrates. A good example is atrial fibrillation. Until recently, atrial fibrillation was considered to be a homogeneous entity, at least by ECG criteria. However, rather than a specific cardiac arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation is now being revealed to have a variety of electrophysiological mechanisms (associated with multiple wavelets and/or increased focal atrial automaticity from the pulmonary veins or other areas) and to represent more of a common end-stage dynamic in a variety of settings than a uniquely defined disease. A more refined understanding of this ancient arrhythmia may help develop more appropriate therapies and preventive strategies, ranging from pharmacological to ablational.

As a useful exercise, readers are encouraged to further examine the dictionary definitions given above and to develop their own conceptual framework for health and disease. Address, for example, the following two questions:

The interwoven processes of constantly rethinking assumptions and researching information are fundamental to practicing medicine successfully, to avoiding potentially lethal errors, and to advancing ways that are both rigorous and compassionate in the inseparable scientifically informed practices of prevention, palliation, and healing.

Clinicians have two major, complementary responsibilities to their patients. We conclude by returning to a central theme of this book, enunciated in the Preface. The successful practice of medicine and the advancement of medical science are rooted in the interwoven processes of constantly rethinking assumptions and researching information. Toward this goal, clinicians have the following two major, complementary responsibilities:

Yet the definitions of these terms, on which the health care profession is based, remain surprisingly elusive.

Notes

*A syndrome well known to golfers, especially experienced older ones, is an affliction that has been called the “yips,” which is characterized by sudden jerky movements, tremors, or freezing when trying to perform a golf shot, notably putting. Current evidence supports the concept that some cases of the yips represent a focal dystonia, the same family of task-specific cramping pathologies that can occur during writing and musical performance.

*Dynamical is not a misprint here. Rather it is a term derived from the study of complex systems (Chapter 9) and is different from the term dynamic. The latter implies change and variability, but not necessarily a coherent set of mechanisms or a set of governing rules. A dynamical system is one that evolves to some type of rules but may also involve random influences.

*This term actually has objective, albeit somewhat arbitrary and evolving definitions. It was defined initially by Drs. Robert Petersdorf and Paul Beeson at Yale University School of Medicine as the triad of (1) fever higher than 38.3°C (101°F) measured on “several” occasions, (2) persisting without diagnosis for at least 3 weeks, and (3) after at least 1 week of determining an etiology as an inpatient. This is now termed classic FUO, due to recent revisions of the definition. Newer criteria call for (1) three outpatient visits or 3 days in the hospital without determining a cause for fever, or (2) 1 week of “intelligent and invasive” ambulatory investigation. What are potential flaws in this newer definition?