CONQUERING THE SLOPE

Building and Writing the Mountain

On September 1, 1954, the first day of the school year, which was also my first day in first grade, we moved to the other end of Hadar HaCarmel. We were now farther from the colonial city hall and Memorial Park, as well as from the historical Technion and its garden. But we were closer to the central landmark of our family life—my father’s store. It was located on the ground floor of the rounded Bet Talpiot building, which observed the point where the horizontal Herzl Street bids farewell to Arlozorov, as it branches off and climbs diagonally toward the top of the mountain. Our new home, 85 Herzl Street, stood higher on the slope than our old house and was only a little over a mile southeast of it. Nevertheless, it felt as if we had come to an entirely different neighborhood.

Looking back, I think my parents must have had a special affection for intersections. Attached to Bet Talpiot, where they bought the store in 1952, was the stylized passage that crossed the two main horizontal streets of Hadar HaCarmel: the parallel Herzl and HeHalutz Streets. Similarly, the apartment building to which they decided to move in 1954 stood at the crux of a T-shaped intersection that served me faithfully for my entire childhood and youth. The short arms of that ‘T’ spread in either direction along Herzl Street. Usually, I would turn right (westward) upon leaving the house: every morning from third grade until I graduated high school, I would walk scarcely three minutes to the Alliance School and sometimes continue on to the store. Occasionally, I would turn left, eastward, to the pharmacy, where we bought chamomile tea, whose smell I cannot bear to this day. Farther east lay the Lysol-drenched Barzilai Clinic, which we visited when we were sick. Continuing in the same direction, we would arrive at the Rushmia Bridge on the way to Neve Sha’anan, whose green slopes we could see from our terrace. But we hardly ever wandered that far.

The central arm of our “T” was Bar Kokhba Street. From the day we arrived in our new house until the day I left Haifa, again and again I would conquer the mountain with my feet, beginning with that street. Bar Kokhba emerged directly across from the house on 85 Herzl, climbed up the mountain, and formed my constant link to the heights of the Carmel. I used to cross Herzl Street, leaving behind the trees planted on its sides, the store windows, and buses and walk straight ahead up the hill.

On my way to first and second grade at the Ge’ula School or, later, to the Scouts, which met there, I would walk past Yavne, the religious school for boys; peek into the store of the kind shoemaker; breathe in the scents that wafted from the neighboring pastry shop; then cross a small side street and continue to the end of Bar Kokhba, where it is cut off by Hermon Street. At that corner sat a nursery school, its small yard filled with swings and slides. About seven years before I arrived in that neighborhood, Yehuda Amichai rented a room on the nearby Gilad Street.1 This was long before he was known to the country and the world as a great poet. In the morning, on his way to teach at the Ge’ula School, he would pass this toy-filled yard, and in the evenings he would describe it in the letters that he wrote to his beloved Ruth in New York. From that corner Amichai would continue his ascent up the steep Betar Street, which leads directly to the Ge’ula School, just as I did. After glancing at the nursery, I would walk along the western sidewalk of Betar, almost touching the thick hedgerow, the living fence that accompanied the upper part of the street. I would try to peek through and see the mysterious house hidden behind it, until I arrived at the horizontal HaShiloah Street.

At the corner of Betar and HaShiloah stood two modern buildings, which hugged the slope, and a lush public garden that cuddled it. The two buildings were erected in the late 1930s and were the first public buildings in the Ge’ula neighborhood, albeit very different from each other. The former Magen David Adom Trauma Center curved humbly along the turn of the street, while the Ge’ula School rose sharply across from it on the rocky ground between the parallel HaShiloah and Bezalel Streets.2 Surrounded by a large yard, the Ge’ula School dominated the intersection from its height. Amichai, the perceptive junior teacher-poet, reported how this lookout from the school windows toward the lower HaShiloh Street changed from an advantage to a liability during the 1948 war. From their classrooms, his pupils saw shot-up city buses unloading wounded passengers at the Magen David Adom.

The public garden adjacent to the Magen David Adom building has two entrances. The steps at its heart connect HaShiloah to the sharp turn of Arlozorov Street above. On Arlozorov stand the venerable Struck House and the Itzkovitz House, both designed by Alexander Baerwald, the architect of the Technion. In 1940 the Itzkovitz House became the home of Haifa’s rabbinate. The apartment building where my mother lived before she got married was also on that street. The public garden that connects Arlozorov and HaShiloah is called Struck Park, after Hermann Struck, the artist whose home hid behind the hedges that surrounded it like an abandoned castle.

Near the lower entrance to Struck Park, the vertical Betar Street crosses HaShiloah, ceases to accommodate cars, and continues upward as a narrow alley designated for pedestrians. The Betar Alley leads to the gate of the Ge’ula School and continues a little bit farther on its way, until it meets the horizontal Bezalel Street. At that corner rises the Dunie Weizmann Music Conservatory, a building that resembles the rounded hull of a ship, or an iron with its tip pointed downward. Next to it, Betar again changes its skin—no longer an alley, but a bank of steps. The Betar Steps: One of the step paths that cuts through the horizontal streets of Hadar HaCarmel on the side of the mountain, creating the wonderful grid of the quarter. The Betar Steps are a relative, of sorts, to the classic Donkey Steps, the ancient Haifaian transportation route and a feature of many mountainous Mediterranean settlements. We would be drawn from everywhere in the city, as if by magic strings, to the webs of these stony stairs that stretch up the side of Mount Carmel. Indeed, when I asked the author Avraham B. Yehoshua, who lived in the city for decades, which of his books was the most Haifaian, he answered without hesitation: “The Lover!” In it, even before love blossoms between an Arab boy and a Jewish girl, their creator brings them together to those very steps. Yehoshua seems to imply in this book that these steps are the expression of pure, romantic Haifa, the city where a love that crosses boundaries is possible.

Corner of Betar Steps and Bezalel Street, near the Ge’ula School

Courtesy of Haifa City Archives; photographer Zoltan Kluger

I remember seeing the bottom tip of the Betar Steps from the entrance of the Ge’ula School both as a pupil there and later, once I joined the Scouts. As Scouts, we often went out to the as-yet unbuilt areas of the Carmel slope, which were an easy walking distance away. From the schoolyard, we would march in strict rhythm out of the gate, turn left on the alley, and then left again on Bezalel, and take it eastward all the way to its end, where it meets the straight Ge’ula Street above it. On the north side of the street stands 21 Ge’ula, the house where the doctor and author Yitzhak Kronzon spent his childhood and youth. I did not know Kronzon then; when I marched by his house for the first time with my Scout group, he was already in medical school. In his stories he resurrects the Ge’ula School and the sounds of pianos that rose from his neighbors’ apartments. With a bittersweet smile, he incessantly lists the names of the small streets he would climb up and down, the streets that led to the still-untamed portion of the Carmel, which we affectionately called “The Mountain” (HaHar), as if there were no other mountain in the world.

About a hundred footsteps from the meeting point of Bezalel and Ge’ula, the houses ended. We continued marching in threes, an excited group of girls with our beloved Scout leader. The unforgettable landscape of Haifa spread in front of us, as if laid out on the palm of our hand.3 On our left the slope rolled all the way down to a deep valley, the Rushmia Wadi, a green mountainside with scattered stone houses and natural caves that gaped into it. The bay glistened at the bottom and the two refineries stood upright in the east.

Author’s friends at the end of Ge’ula Street, with the Rushmia Wadi and the bay behind them

Courtesy of photographer Zvi Roger

To our right were the quarries, a white gash in the landscape. As we marched, we would sometimes hear the screams of barda! and know that in a minute, the rocks would explode.4 We would continue along the busy sidewalkless road that connected Hadar HaCarmel to the upper neighborhoods on the mountain. A few minutes later we would leave the paved road and walk up a wide dust path to the aptly dubbed Eucalyptus Grove nearby. On long summer Saturdays we would venture farther, to other enchanted spots on the mountain, whose paths and rocks, bushes and trees, pine needles and fallen pinecones, were imprinted in our hearts forever, along with the sea, sparkling in the distance.

Far in the future, lines from a poem by Dahlia Ravikovitch, who spent her sad youth in Haifa, would send us back there:

The woods of green sheep flowed down the slopes

and the sea below splashed and turned blue in the sun.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

and we were still girls.5

The Ge’ula School

At first, my father would take me to the Ge’ula School in the morning, before he went to the store. We would cross Herzl Street, starting our climb on the middle arm of “our” T, that is, Bar Kokhba Street, and continuing on the street above it. Afterward, we would cross HaShiloah Street and then ascend through the alley. The conservatory faced us, and to our left was the low iron gate of the school.

Even before I crossed through the gate and entered the school premises for the first time, my heart was drawn to the thick-trunked eucalyptus tree, which I could see from the alley. The tree stood at the edge of the giant schoolyard and rose up to the sky, while its long-leaved branches bent down toward us. Next to it were steps that led to a smaller yard, partially roofed, that spread between two buildings. By these steps I bid my father farewell and joined the pupils of the first grade, who stood there in front of a thin man whose round glasses especially impressed me. The teachers arranged us in pairs, and then we turned right to the smaller western building that—as I found out later—housed the lower grades. We went up to the first floor. Our first-grade classroom is left of the steps. We enter a large, light-bathed room, with our teacher, hamora Rina. Her light, curly hair combed backward, her eyes small and blue, her smile warm and pleasant, and she is a little chubby. I immediately knew that I would love going to a real school with rows of desks and a teacher standing in front of the class.

The Ge’ula School, the eucalyptus branches hovering over the steps

Courtesy of Haifa City Archives; photographer Zoltan Kluger

Kronzon, who attended Ge’ula before I did, remembered that first day in darker tones:

A scary man in a gray, wool suit and thick-lensed glasses wandered around the yard and screamed in a voice hoarse from smoking, “First grade here, first grade here!” . . .

The scary man said, “I am the vice principal Haklay.” . . . Mr. Haklay screamed at the parents . . . to go home. . . . One boy started crying. . . . Mr. Haklay approached him and yelled next to his ear, “Stupid! If you don’t stop immediately, we’ll send you back to kindergarten.”6

From that moment on, Kronzon the boy was afraid to cry at school, but that did not prevent him from loving his first-grade teacher, Ziva, “the first and the admired one,” for eternity, exactly the way that I loved my teacher, Rina.7

For the first few days of school, my father walked me all the way to the schoolyard; later he just took me to the rounded building at the intersection with HaShiloah; and, finally, he walked me only up to Hermon Street. In this way, he gradually weaned me off of my dependence on him. In 1954 Herzl Street was a major two-way thoroughfare, and there was no light at the intersection I had to cross. My father taught me to look both ways and to observe and follow the behavior of the adults crossing that street, but he continued to help me cross Herzl Street for many months.

The autumn days of first grade were as bright as the face of hamora Rina.

I had a small rectangular notebook, a kind of half notebook, a pencil, and an eraser. On Hanukkah, after we already knew how to read, we received our very first reader in a party for all first graders. One of the children played the wise dwarf, a pointed cap on his head: “There was a dwarf in the past / All night he studied so fast / One day he got up / And behold he was smart!”

But in the middle of the school year, we found out that hamora Rina was pregnant and a short time later she said good-bye to us. My mother and I went to visit her to give her a present after she gave birth. Rina served us chocolate candy, flat and round, on top of which were scattered sweet, small dots in a variety of colors—nonpareils. Since then, every time I see nonpareils, I think about that visit at hamora Rina’s. Her replacement was the tall, chopped-haired Sima, whom I did not like. She was my teacher in second grade as well, at the end of which my parents transferred me to the Alliance school.

The Ge’ula Elementary School or, as it was initially called, Amami Bet (P.S. 2) was built due to the boom in the Jewish population during the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s. Initially independent, the Ge’ula vicinity was absorbed into the district of Hadar HaCarmel, which spurred the construction of a public school in the neighborhood. The Committee for Hadar HaCarmel, aware of the grave need for appropriate facilities for educational institutions, allotted grounds for the school and pursued its quick construction.8 Ge’ula was the second public, or “folk,” school in Haifa. P.S. 1, established in the 1920s with the support of the private Reali School, preceded it. P.S. 1 provided the new school with veteran teachers like Mr. Ya’akov Haklay, who would eventually become its principal. Following the model of the Reali School, Public School 1 contributed to the emphasis on physical education in the Ge’ula School as well, incorporating the Scouts movement into the curriculum.9

Magen David Adom Trauma Center, with Struck Park on the left

Courtesy of Haifa City Archives; photographer Zoltan Kluger

During the development of the Ge’ula neighborhood, another public building, Magen David Adom, the first free-standing trauma center in Haifa, was constructed across the street from the school. A sign in bronze letters on the façade of the building testifies to its glorious past: “Magen David Adom, 1938” and, above the letters, the six-pointed Jewish star. The building was designed by the engineer Gedalya Wilboshevitz, one of the builders of the Technion and one of the founders of Hadar HaCarmel. A metal plaque still affixed to the building commemorates the builder’s son, Alexander, who died suddenly in 1932.10 Wilboshevitz’s Magen David Adom building boasted a smooth, clean façade and a special awning above its entrance. Its rounded form nicely solved the problematic meeting of HaShiloah Street and the steep Betar.

At that intersection, a bit higher on the Carmel slope, lay the plot of land designated for the Ge’ula School, sandwiched between HaShiloah and Bezalel.11 It was a narrow lot, akin to an asymmetrical trapezoid. The original plan of the school included one long, multistoried building on the eastern edge of the lot, following the incline of the ground. Its wide windows all faced westward toward a large yard. The basement floor contained workshops for crafts as well as a cafeteria and kitchen, while offices and classrooms were on the upper floors. In the middle of the long structure was a staircase that split into three branches. The entry was beneath the roof that attached it to a smaller building, which held only the bathrooms (over the years that smaller structure was expanded into a building for the lower grades).12

The Ge’ula School was designed by the architect Max Loeb, considered “one of the pre-eminent exponents of Modern architectural style in Palestine.” He was born in Kassel, Germany, in 1901 and studied architecture in Dresden and Munich, but ultimately earned his diploma in 1925 at the Technische Hochschule Darmstadt. Loeb grew up in a Zionist home and visited Palestine when he finished his studies. In 1929 he immigrated there and joined a Jerusalem firm, where he planned and built the main branch of the Anglo-Palestine Bank as well as some private residences that were clad in stone but were modern in form.13 Yet Loeb’s place in the annals of the country’s architecture is preserved in no small part due to his innovative plan for the New Business Center in the lower city of Haifa near the port. His design was “extreme in its simplicity” and remarkable in its “unity and diversity” as well as its “disciplined flexibility.”14 To supervise a project of such massive dimensions, Loeb moved from Jerusalem with his business partner in 1934, settled in Haifa, and, before the center was even completed, became a sought-after architect.15 He planned the first printing house in the city in addition to a variety of businesses and residences. In 1936 photographs of his New Business Center in the lower city were published in the journal Architecture d’Aujourd’hui as a prime example of urban architecture worthy of international attention. That very year he also won first prize in a competition to build the Central Synagogue of Haifa for a design rich in contrast, which was simple yet full of grandeur. This ambitious plan, however, was never executed, despite protests from Haifa’s Association of Architects and Engineers.16

Loeb, who believed that architecture in Palestine should be a harmony between “material, form and landscape,” was also renowned for the schools he planned.17 Julius Posner, another German Jewish architect, praised Loeb’s village schools in a 1938 article published in the Palestinian architectural journal HaBinyan baMizrah haKarov (The building in the Near East). Posner evaluated the schools based on educational, health-related, and structural categories.18 He commended Loeb for considering the local climate while planning the multistory Ge’ula School by placing the windows on the western side to avoid exposure to the heat and light from the east.

Posner, however, criticized city planners in Palestine for failing to allot appropriately spacious grounds for schools and settling instead for lots devoid of open space and greenery, squashed between buildings and streets. With Ge’ula, Posner complained, “the constriction of the lot causes an arrangement of elements that does not seem ideal to us.”19 However, he emphasized that Loeb’s hands were tied, as placing the building on the opposite side of the lot would have resulted in even greater deficiencies.

Despite its limitations—topographical and otherwise—the Ge’ula School faithfully served generations of students, and its original plan proved flexible enough to enable expansion both upward and laterally. When I attended this school in the mid-1950s, it had already been expanded.20 Grades one, two, and three studied in the small building on the west side of the lot, while grades four through eight were held in the original building. The younger children played in the small, partially roofed yard between the two buildings, but when it rained, many pupils, big and small, gathered there. Another rainy-day option was at the northern tip of the large yard, where a newer building on stilts provided an open yet sheltered area perfect for games. The school cafeteria on the basement floor transformed into a synagogue on Saturdays, and on the other side of that floor was the gym, with floor-to-ceiling wooden ladders covering the entire eastern wall.21 This was also where students gathered and school plays were performed. Every morning, in the giant yard that belonged to the “big kids” during recess, the daily assembly was held. After the assembly the pupils walked in unison to their classrooms to the sound of popular marches played over the loudspeaker.22 This daily ritual was conducted by Mr. Haklay who, by my time, had already become the principal.

I ran into Haklay’s name many, many years later, during my research on Amichai, the poet. I found out that when Haklay offered Amichai—then Yehuda Pfeuffer—a position at the Ge’ula School, he demanded that the young man Hebraize his German last name. Thus the name “Yehuda Amichai” was born. Haklay’s daughter, Ora, was the poet’s cherished friend and colleague during his time teaching at Ge’ula.23

Literary Accounts of the Ge’ula School

It so happens that the Ge’ula School was exceptionally lucky in the documentation of its early days. One of the most important periods in its life was recorded by two gifted, yet very different, authors, whose lives intersected with its own. While the time they spent under its roof overlapped, their paths did not. One was a rookie teacher, the other a student. One came from Jerusalem and stayed in Haifa for eight months (August 1947–April 1948); the other was born in Haifa and spent his formative years at that school (1945–53). One was a German Jew, who—though he’d been mischievous during his childhood—believed with all his heart in instilling “regular itineraries,” order, and discipline; the other focused mostly on subverting the rules that Ge’ula’s teachers and principals tried to impose.24 What’s more, their written records themselves are dramatically different: the first wrote letters to a single addressee in real time as the events were unfolding; the second waited over three decades before retrieving his autobiographical stories from memory.

The first of the two “documentarians” of the school was the poet-to-be Yehuda Amichai, who taught at Ge’ula for less than five months, over the course of which he wrote sixty-seven of the ninety-eight letters he would send to Ruth. Haifa was a new city for him and teaching a new profession; also new was his status as a man who saw himself as engaged to a woman on the other side of the ocean. In his romantic letters to her, Amichai’s pen captured the school’s everyday life and even Loeb’s design, like a camera that captures every object in front of it, regardless of whether it was only coincidentally in the frame.

The second is Yitzhak Kronzon, a renowned Israeli cardiologist who lives and works in New York City. His bar mitzvah ceremony took place in 1952 in the cafeteria-turned-synagogue in the Ge’ula School’s basement. This school was at the center of the boy’s universe and later would play a key role in his stories, together with the small slice of Haifa around it.

That very institution was also a central fixture of Amichai’s life in Haifa. Indeed, caught within the frame of his epistolary camera is the everyday life of Ge’ula. He, the fourth-grade homeroom teacher and English teacher for the fifth and sixth grades, meticulously depicts how the large yard changes its face over the course of the day. In the mornings the daily assembly is held there, and each homeroom teacher stands at the head of his pupils. Amichai feels that “forty pairs of eyes of all colors” follow him.25 During gym class the yard becomes a training ground—forty-two children, all in white uniforms, crouching under the shadow of the building, while “the teacher Amichai stands in front of them.”26

And finally, at 4:30 p.m., during recess, when he is the teacher on duty, “the sun goes west over me and my shadow is cast long over the yard.”27 Due to the shortage of classrooms in 1947, school hours were lengthened to accommodate two shifts, so both the yard and the teachers had to work overtime.28 When winter approached, joyful songs about rain wafted from the classrooms, and during recess the yard became a gauge of the “changing seasons.” As the “cool days” neared, the children’s games became “increasingly energetic.”29

Through his letters Amichai also captures the broad stairs separating the small yard from the large one as well as the wide entrance gate. “Streams of children” flow through with ease, and at the end of the day Amichai the “photographer” zooms in on the girls’ skirts, wrinkled like an “accordion,” from extended sitting.30 The large hall in the basement also peeks out through the letters, albeit not during gym: “I was with sixth grade in the hall. A broadcast [began] about . . . the river of Mark Twain and the boats.” In this letter Amichai draws an almost surrealist picture—eleven-year-old pupils in 1947 Palestine listening attentively in the school gym to the sounds of the Mississippi River, the bass voice of Paul Robeson, and the “songs of the black people . . . in the cotton fields.” As his pupils listen to the broadcast, Amichai writes that “curious trees stretched their branches through the window.”31 The teacher-artist who, within a few years would write the famous lines, “Of three or four in a room / There is always one who stands beside the window,” is keenly aware of the value of the giant windows Loeb set in the western wall: “the windows in our classrooms are very large, a kind of a wall that is all glass.”32 While the pupils are busy with their work, he gazes out at the world and dreams up visions. One time he imagines that his beloved has returned from America and is crossing “through the yard.”33 Another time he looks beyond the yard and the nearby buildings and sees the ridge of the Carmel, and, for him, it is reminiscent of Mount Moriah.

The thoughts about Mount Moriah, and the altar that Abraham built on it, pop into Amichai’s head after one particular Friday in the middle of November 1947. On that day there was an attack on the bus that Amichai and his friend and colleague Ora Haklay were taking to a party on the Carmel. Seeking revenge for the blood of their friends shed by the Lehi, the radical Jewish underground, British soldiers fired on the Jewish bus as it turned near the top of the mountain.34 Hayim Goldman, a young man sitting with his girlfriend in the seat right in front of Amichai, was killed. Miraculously spared, Amichai wrote to Ruth that the sight of the Carmel from the school window elicited in him the memory of “the place” (hamakom) where the binding of Isaac happened, as if the innocent Goldman had been a sacrifice, a kind of offering that had been accepted on the Carmel.35

Amichai’s bus was attacked two weeks before the November 29, 1947, vote for the Partition Plan, after which the war erupted that would cost the lives of 1 percent of the Jewish population in Palestine. In the nascent Israeli literature of the time, the binding of Isaac became a symbol for a generation of young men and women whose lives had been sacrificed for the State of Israel, with no ram to save them. Thus, standing by the window of the Ge’ula School, Amichai foretold the trope that would dominate the poetry of that generation.36

At that same time, in the middle of November 1947, the young Yitzhak Kronzon was a third grader at Ge’ula. Amid the growing tension, no one knew how events would turn out, but two weeks later, after the partition vote, the world of Hadar HaCarmel’s residents turned upside down, as did that of everyone in the land. Even the littlest children at the school realized that their life routine would be unrecognizably changed. The Ge’ula School was in turmoil. On one floor the draft office of the Hagana resided. Another housed Jewish refugees from the mixed neighborhoods in the lower city.37 Mrs. Mintzberg, Kronzon’s teacher in “class 3-B in the Ge’ula School,” bragged to her students that “her Gedalya, who is fifteen years old, lies with a Sten all night and shoots Arabs” and the boy Kronzon was disappointed that his father, a vital worker at the Electric Company, had not been drafted.38 On December 21 Amichai recorded his students’ Hanukkah vacation compositions in his letters. They all complained about the curfew. Moshe wrote that “the Arabs started attacking”; Ziva: “they killed Jews”; Edna: “my father had to be on guard duty”; and Giyora: “a bullet entered the bathroom.”39 It was hard for the teacher to do his job, but he was determined to distract the nerve-wracked children and would rather that they “feel that a mistake in arithmetic is terrible, not the shots outside.”40 Like the other teachers, Amichai tried his best to maintain a sense of normalcy for his pupils.

The Magen David Adom building, which had stood calmly across the street from Ge’ula since they were both built, was seized by a frenzy during that period. Starting in December 1947, Arab forces frequently attacked Jewish vehicles, and the many wounded arrived at the trauma center—the only one in Haifa—bleeding, to be treated. For the first time, Ge’ula students looked out at their familiar neighbor with fear. Amichai wrote to Ruth that at the Magen David Adom near the school, “two buses arrived. . . . The windows were punctured by bullets. . . . The children in the classroom begin to cry. . . . Fifty-one wounded . . . the other passengers stained with blood.”41 The anxiety of the children distressed Amichai and dampened his spirits. He did not yet know that within two months he would share far worse traumas with pupils at a different school.42

Likely due to censorship, Amichai did not mention—not even in one word—that Ge’ula was one of the main weapons storage facilities of the Hagana Central Command, even though, as an active member, he surely knew this.43 Nevertheless, he did hint to Ruth about “matters” that kept him busy during the nights.

On January 23, 1948, Amichai bid farewell to his Ge’ula pupils because he had been transferred to the HaMerkaz School in the heart of the Arab-dominated lower city, which had become a battlefield. In March, after two months away from Ge’ula, he speaks of a visit there and how he was surrounded by the love of the children, his former pupils. In comparison to the school where he now taught, life at Ge’ula seemed almost normal.

On the eve of Passover, on April 22, 1948, the Hagana forces in Haifa took over the city. Eleven days prior to that, Amichai received the Dear John letter from Ruth, ended his correspondence with her, and went south to the Negev, where fierce battles were raging. Amichai’s account of Haifa, then, stopped midwar. Sixty-eight years later Kronzon fills in the subsequent chain of events at the Ge’ula School. It is as if an unseen hand motivated the seventy-seven-year-old author to reveal what, exactly, happened from Passover 1948 through the end of that fateful school year, at the school that, like the city, was now under full Jewish control. In a story published on Independence Day 2016 in Ha’aretz, he writes,

When we returned to the Ge’ula School after the long Passover vacation, it became clear to us that we would not be able to study in it any longer because it was occupied by refugee children who were forced to leave the kibbutzim of the Jordan Valley. Instead, all the pupils of our school were transferred to the second shift at the technical school at Masada Street, on the corner of Balfour, next to the stone tower that stood there then.44

Indeed, before Passover, studies had been conducted in the Ge’ula building despite its role in sheltering crowds of Jewish refugees from Haifa’s Arab neighborhoods. But after Passover, when those Jewish refugees could return to their homes, everything changed. The school building was taken over by the Jewish National Authorities to house the evacuees of the Jordan Valley kibbutzim that had been attacked by the Arab armies. Every day between two and six in the afternoon, Ge’ula’s regular pupils had to make their way to a farther school building. Kronzon’s teacher continued teaching the third grade in its temporary home. She promised her pupils that “on one of the last days of the school year . . . she would teach them the new popular elegiac song that was playing on all the radios, ‘In the Vast Plains of the Negev, a Defending Soldier Fell.’”45 In Haifa war no longer raged. But in Ge’ula once again there were refugees. The former fourth-grade homeroom teacher, Yehuda Amichai, became a “defending soldier” in the terrible battles in the Negev Plains and survived. He never returned to live in Haifa.

After the summer of 1948 Ge’ula returned to being a full-time elementary school, and Kronzon studied there until he graduated at the end of eighth grade. His bar mitzvah in Ge’ula’s basement synagogue would later feature in the story “Mother, Sunshine, Homeland.” Its climax is the author’s belated recognition of the truth behind the bar mitzvah sermon that had been composed for him: “There are three things without which the spirit of man cannot subsist: mother, sunshine and homeland.” Of course, when he was thirteen years old, the wisdom of the sermon’s words paled in comparison to both the gifts he received and one particular compliment from the school caretaker, Velgreen, who served as the sexton of the synagogue on Saturdays. He “said that he’d never heard anything quite this good.”46

Unfortunately, the narrator’s bar mitzvah success does not reflect his standing in other areas. In “organization and cleanliness,” for example, he was known as the “absolute worst” pupil. “Once a month, the nurse Chodorovski came to examine us,” he writes. To demonstrate the difference between a clean boy and a dirty one, she chose two children to display in front of the class: “Yoram,” who was the “cleanest” child, and the narrator, as a counterpoint, a “dirty child.” She listed the details that separated the clean from the dirty: “The clean boy wears polished shoes and his socks are clean and folded down. The dirty boy doesn’t wear any socks, and has no lace in his right shoe.” Kronzon, the child who was humiliated by the nurse but has since become a successful physician, concludes, with a mixture of humor and bitterness, that this is how he “entered the history books of the Ge’ula School.”47

In addition to describing his school, Kronzon’s narrator repeatedly relates the names of the streets that surrounded it. Their eternal ascents and descents dominate the stories, the fantasies of their author, and the lives of their heroes. The main character of “Musical Education,” for example, stops learning the piano because he fears “a large dog that liked to loiter by the Betar Steps” at the exact same time that he would “gather the music notes into the dark blue cardboard binder with a gold harp imprinted on it, walk down the Betar Steps and then over to Shiloah Street, to perform the exercises.” The musical career he had begun was cut short because the only alternative to the Betar Steps was a “lengthy route that traversed Tavor, Bar Kokhba, and Arlozorov Streets, which took hours.” This sabotage of his musical education was ironic because his mother was a piano teacher: “Anyone walking on late Saturday mornings along Ge’ula Street, from the synagogue to the quarry on the far end of the street, would hear Mother’s pupils conscientiously practicing.”48 Everyone played the piano except the son of the piano teacher.

In the overwrought drama of yet another story, the Betar Steps star in an imaginary scene dreamt up by the child narrator. These were the days of the war, and Kronzon, whose father was not drafted, wished that Shaya, his mother’s former suitor, would visit. He had never met Shaya, but had seen him in an old photograph, decorated with medals, as a war hero: “I used to look lovingly at . . . the photograph and pray for him to return to our family with his uniform and his pistol. I would fantasize walking down the Betar Steps with him, hand in hand and into class 3-B in the Geula School.”49 The Betar Steps become a vital component in the boy’s fantasy of parading his hero through the neighborhood.

The sexual development of the narrator of these stories is also bound with the city’s topography. On Friday, “the best of days,” he and his friends spy on the most intimate moments of the residents of Ge’ula Street. But before he reaches the climax of his story, the narrator must explain the terrain. He lists the bus drop-off points in Hadar HaCarmel for the workers in the Bay Area factories. Indeed, the map of bus stations, apartment buildings, streets, ascents, and steps and the specific relationships of time and distance between them are crucial elements in his story:

First . . . the Shemen Factory workers arrive because their bus stops next to the yeshiva [on Ge’ula Street]. . . . The ones from Fenitzia . . . disembark from their bus on Herzl Street, and they have to walk much farther through the Betar Steps. . . . Eli, the son of Vackerman, from Fenitzia, got married and started working at the Shemen Factory. I told you that those from Shemen arrive home earlier. . . . Every Friday at one, we stand on the terrace . . . and see how Eli Vackerman . . . runs up the hill . . . into their apartment on 28 [Ge’ula] . . . and quickly screws his wife . . . because he has only about a quarter of an hour until his father, who lives with them, gets there via the Betar Steps.50

To the great joy of the peeping boys, the young husband hurries home from the bus stop, knowing that he has fifteen minutes of grace thanks to Haifa’s hilly topography and the ascent the father must climb from the Herzl Street stop to their home on Ge’ula.

Arlozorov Street and Baerwald’s Residential Designs

The Ge’ula neighborhood and the clusters of houses around it were finally established at the beginning of the 1930s, east of Aliyah (Ascent) Street after a protracted real estate saga. Until then, the street had marked the easternmost border of Hadar HaCarmel, the “garden city” that sprouted up around the Technion in the 1920s on the shoulder of the mountain. Aliyah Street itself, so named mostly due to its steep diagonal route that connected Hadar HaCarmel’s main street to the top of the mountain, became, with the establishment of Ge’ula, a central thoroughfare. In fact, only after construction on Ge’ula Street began was Aliyah paved and extended to meet it.51 Its name was changed to “Arlozorov Street” later, when Chaim Arlosoroff, the young Zionist leader, was assassinated in Tel Aviv in 1933. After an arduous climb up the mountain, this street swerves suddenly, turns westward, and creeps slowly upward, crossing Balfour Street and making its way toward the center of the Carmel.

In 1913, however, when the Jewish artist from Berlin, Hermann Struck, bought a piece of land on the side of the mountain, Hadar HaCarmel did not yet exist, nor did the ascending street that would mark its eastern border. When Struck and his wife, Malka, immigrated to Palestine nine years later, they found temporary housing in the vicinity of the Technion, at the heart of a burgeoning Hadar HaCarmel. The artist asked his friend, the German Jewish architect Alexander Baerwald, who had built the Technion, to design a home for him and his wife on the sloped lot he had acquired a decade earlier. Perhaps due to the ten-year gap between Struck having acquired the lot and the construction of the house and paving of the street, the house’s entrance is far below the sidewalk. In fact, because of the steep ground, its roof is almost level with Arlozorov Street.

The many visitors to the Struck home used to walk down the steps and through the well-groomed botanical garden that had been planned along with the beautiful house: “from Aliyah Street [later Arlozorov], one passes through a fragrant garden, iris, cyclamen, pomegranate, all in good taste. On the other side of the fence, the wild, rocky terrain of the mountain still spread,” wrote Meir Ben Uri, Struck’s loyal student, years later.52 The artist’s dedication to gardening determined not only the nature of the garden but also the plan of the house—in its cellar Baerwald built a private cistern that supplied the water needs of the garden and freed its owner from dependence on the distant well of the Technion.

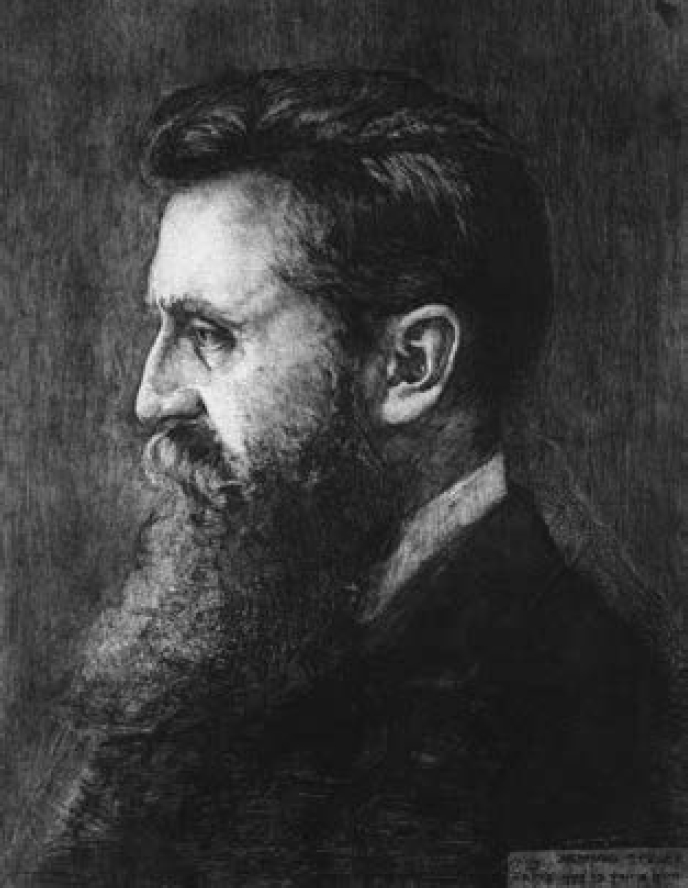

Thanks to his expertise in horticulture, Struck was Baerwald’s partner in designing the Technion and Reali School gardens. But the two Berlin friends shared much more than a love of gardens. Both the architect and the painter were Zionists who believed that construction in the nascent Land of Israel must integrate Jewish and local elements and draw from the eastern lexicon of forms. Struck eternalized his close friend’s face in an etching in 1927, and after Baerwald’s death in 1930, he painted an image of his tombstone on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem.

The home that Baerwald built for the Strucks on the steep slope of the Carmel incorporated the geometry of the Arab structures in the region, but the design of its interior was adapted for the needs of its Western tenants.53 Baerwald used an architectural vernacular that exudes its indigenous nature—a series of interlocking cubical forms lie one on top of the other to become a part of the slope. The arrangement of the cubes in the Struck House creates a dramatic effect and does not blur the geometrical purity of each one of the forms.54 Yet it is not only the silhouette of the building that is similar to the local houses—both the materials and the pattern declare, so to speak, that they were born here: the deliberately rough chiseling of the stone exterior, the pointed arched openings reminiscent of Islamic structures, and the railing wrought in an Eastern style. The Struck House is a quintessential example of the Baerwaldian residential architecture whose power lies in merging with the topographical environment. His style mimics Arab buildings in mountainous regions, mindful of the climate as well as the building’s practical function. Because the house was designed as both the artist’s residence and work studio, the large windows were placed in the northern wall, to provide the preferred light. The adjacent external stone steps and the flat roof, typical of Arab construction, perfectly served the artist who wanted to paint from the building’s heights.

When, in the spring at the crack of dawn, the first lights appeared over the mountains of the Galilee, illuminating the sky with colors of fire and smoke, Struck stood on the roof despite the cold, the brush in his hands, his beloved pipe in his mouth, and painted, and looked out . . . and waited . . . for the special clouds that produced an extraordinary atmospheric phenomenon that he loved: . . . the wonderful morning light and the mist gave an otherworldly quality to the color of the bay, the sea and the mountains.55

Struck House, restored, 2014 Courtesy of photographer Adi Silberstein

This lyrical scene, recalled by Ben Uri after the death of his teacher, has been interpreted as an expression of the spiritual quest of the religious artist.56 But it also testifies to Struck’s treasured connection to Haifa; the bond with the actual, physical place was a significant component of Struck’s fervent Zionism. His desire to settle in Palestine stemmed from his attraction to Haifa and its landscape as much as it did from Theodor Herzl’s influence.

Struck was born in an Orthodox Jewish home in Berlin in 1876, and although his family wanted him to be a rabbi, he turned to the Royal Academy of Art in Berlin. When he graduated in 1900, however, the academy prohibited him, as a Jew, from teaching there. Three years later he embarked on an artistic journey throughout the Mediterranean, including Palestine. Only a year had passed since Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, had published Altneuland and, in it, the prophetic description of Haifa as “the city of the future.”57 In his literary vision Herzl saw the slopes of the Carmel covered with charming, white houses and the bay’s port, bustling. When Struck arrived in Cairo during his journey, he met Herzl in the glamorous Shepherd Hotel, the place where Herzl received the rulers of Egypt and England.58 Struck was awed by Herzl, and perhaps at that point he had already made the decision that if he were to immigrate to Palestine, he would settle in Haifa. On his way back from the east, Struck visited Herzl in the bosom of his family home in Vienna and made a sketch of his face. In creating the final etching of Herzl’s portrait, Struck used the vernis mou (soft-ground etching) technique, which preserved his “handwriting,” as if the print were a drawing in pencil.59 Struck captured the intensity that Herzl’s personality radiated and his gaze, like “one of the prophets of Israel.”60 He managed to show the etching to Herzl, and, when Herzl died in 1904, Struck’s portrait of him circulated all over the world and was carved into the collective memory of the Jewish people. Sadly, while this image became iconic, its creator was all but forgotten.

After meeting Herzl, Struck would speak of the leader’s beauty and nobility and also strove to look like him—he grew a beard and would be described as a “tall man, elegant, in a jacket, and a beard, Herzl-style.”61 Yet Struck’s identification with Herzl was deep and essential. In his deeds Struck achieved what the great Zionist dreamer who died in his prime was unable to. “Struck . . . fulfilled the goal of his Zionist longing and built himself a home in Haifa,” wrote the philologist Victor Klemperer, who met Struck when they were both in the German army, as he captured the fluctuation of the artist’s soul in his own memoirs.62 Klemperer recognized that, for Struck, settling in Haifa was the ultimate realization of the Zionist dream, even though one would have expected the religious, Orthodox Struck to settle in Jerusalem. Struck seemed to his army buddy like a sort of Don Quixote, a compassionate “knight” with the image of sorrow.

In addition to its connection to Herzl, the natural beauty of Haifa and the spiritual quality of its vistas attracted the heart of the artist. He decorated his workshop with a painting of the cloudy bay even though he could see the bay, Acre, and Mount Hermon from his window. When a new student arrived, he would take him up “to the roof of his home, place blank paper and a sharp pencil in his hands, and instruct him to draw Haifa’s landscape.”63

Hermann Struck’s portrait of Theodor Herzl

Courtesy of the Open Museum, Tefen Industrial Park

Twenty years after his first trip to Palestine, the artist transported his studio as well as his German furniture from Berlin into the house that looked out from the Carmel over to the sea. His etching press with its heavy rollers and the etching table now lived in Haifa, as did the tremendous book cabinet whose four glass doors guarded a treasure trove of German culture. Outside the entrance, to the left of the door, a marble sign with the artist’s name in German welcomed the guests. Inside, above that door, was a pattern of sunrays that echoed the classic cross-vault of the high ceilings. Against the background of the gray floor, the art deco patterns of the hand-painted tiles shone. Those created a “tile carpet” that attracted the eye of all who entered the house. From the stained glass windows in the northeastern wall of the large workroom on the main floor, a soft light floated in.

But it was not just the content of Struck’s Berlin house that arrived in Palestine. He brought his artistic talent and the respect that he felt toward all human beings. Struck was the premier Jewish artist in the Land of Israel and its most important authority in the field of etching. His genteel house was a hub for various intellectual circles, especially lovers of art, but it also bustled with many students, for Struck was a superior teacher whose students in Berlin included Marc Chagall, Max Liebermann, and Lovis Korinth.64 His love for his new homeland was evident in the public and educational work in which he immersed himself. He continuously supported the Tiferet Israel yeshiva that was near his house and served as a member of a number of urban committees, including those that chose the emblems of both Haifa and Hadar HaCarmel.65 Even during the Italian bombings in World War II, when many left Haifa, Struck not only remained in his home but, “between one bombing and the other,” initiated and presented Haifa’s first graphic arts exhibition, which attracted an audience of thousands, right in the heart of the city.66 And beyond Haifa, Struck was among the founders of the Tel Aviv Museum and the initiators of the reopening of the Bezalel Art Academy in Jerusalem. Yet even as he significantly influenced the development of Bezalel in its early years, Struck was not welcome within its artistic establishment.

As improbable as it may seem, the trajectory of Struck’s life mirrors that of the fictional heroes of Herzl’s utopian novel, Altneuland. After leaving Europe in 1902, the protagonists visit Palestine, then disappear for twenty years until they return to Palestine in 1923, whereupon they discover that it has blossomed and Haifa has become a cosmopolitan city. Similarly, Struck embarked on a journey to Palestine in 1903, was absent from that country for two decades, and then returned. The Haifa to which he arrived in 1922 was only at the beginning of its development, but he witnessed Herzl’s vision for the city near fulfillment during the British Mandate, when it became an imperial, cosmopolitan crossroads.

Yet while we know nothing about the period during which Altneuland’s characters vanish from the plot, the adventures of our flesh-and-blood hero, Struck, could fill an additional novel. Between 1903 and 1922 he achieved international stature and was considered one of the premier etching and print artists of the twentieth century; he created approximately 250 portraits, among them Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henrik Ibsen, and Oscar Wilde. He also etched a series of anonymous “Jewish faces” that the art critic Arnold Fortlage compared to Rembrandt’s portraits.67 Struck was a member of the Royal Society of Print Artists in London and exhibited his works at the modernist Berlin Secession exhibitions between 1901 and 1912 as a member of that art movement. His book on the theory and art of etching, Die Kunst des Radierens, published in 1908 by the Berliner Cassirer Publishing House, became a seminal work. It appeared in five editions through 1922, with the fifth including etchings by Marc Chagall and Pablo Picasso, and it established Struck’s fame as a leading print artist, teacher, and theoretician. A German patriot, he volunteered for military service in World War I, serving as a translator, liaison officer, and military artist. In 1917 he became the referent for Jewish issues at the German Eastern Front High Command, and in 1919 he joined the German mission to the Versailles talks as the councilor for Jewish affairs. Soon after he returned to Berlin and witnessed the rise of antisemitism, Walther Rathenau, the Weimar Republic’s Jewish foreign minister, was assassinated. Despite his professional success and his connections to German government leaders, this prompted Struck to emigrate to Palestine.

In Haifa his art gradually grew simpler and more essential. The circle of the bay and the straight line of the palm tree became his main artistic motif. The continuous clouds that stretch over the mountains bordering the bay were a means to express his unity with the landscape and, in the 1940s, also his fears of the storm of war and the weakening of his body. Struck continued his extensive artistic, Zionist, and communal activities in Palestine, but during his life—and even after his death in 1944—he did not gain true recognition for his contribution to Israeli art.

In the 1950s and 1960s I often climbed Betar Street, east of the Struck House, and peeked at the hidden structure through the hedgerow. The house was already encircled by apartment buildings, but it was closed. Surrounded by dry plants and desolate, it evoked in us children curiosity mixed with fear. We knew nothing about the original owner of the house, other than the name Struck and that he was an artist.

On the other side of Arlozorov Street, a little lower on the slope than the Struck House, stands its younger brother, the Itzkovitz House, which coincidentally holds a unique, personal connection for me. It is one of the last buildings to bear Baerwald’s signature, as it was completed in 1930, the year the preeminent architect died. “The drawings of the architect testify to the talent with which the master approached the study of the entire façade as well as the shape of each opening and its placement inside the entire area of the wall,” states an article written about the house in a Palestinian architectural journal seven years later.68

The Itzkovitz House is closer to the street than the Struck House, and to this day it looks as though it was born out of the tall, exposed rock on which it was built. Because it rests on the opposite side of the street, those who enter it must go up the stairs rather than down—nevertheless, the genetic features of the common father of the two buildings are obvious. The entirety of the Itzkovitz House is made of local stone; its blocks are unequal in size, one set beside the other asymmetrically; its large, dramatic windows and doors are forged in the shape of pointed arches; and its flat roof testifies to the influence of the vernacular Arab style. Unlike the Struck House, however, here, there are also roofed terraces with arcades of classical columns. But like its older sibling, despite its Eastern appearance, the interior layout attended to the needs of the Western tenant.

The house was commissioned by the physician, Dr. Yitzhak Itzkovitz, the owner of the first radiology clinic in northern Palestine and eventually the head of the Physicians Association in Haifa, and his wife, Aliza. She was the daughter of Jacobus Kann, founder of the Zionist Organization in Holland and an enthusiastic Herzl supporter who financed the Zionist Congress. The Itzkovitz family lived there until 1940, when the Italians started bombing Haifa. Then they sold the house to the city’s chief rabbinate, which used it for decades. The wide roof—which Baerwald had planned for the socialite Itzkovitz couple as a space for their popular summer parties—was perfect for weddings. It enabled the rabbinate to raise a chupah under the open sky, according to custom, and provided plenty of room for guests. In August 1946 Rabbi Kaniel married my parents on that roof.

My Family’s Mythologies and Our Last Home in Haifa

My mother used to tell us often about their wedding at the rabbinate at 16 Arlozorov and how her friend Pnina Benish baked cakes and brought them to that roof. Pnina lived nearby at 26 Arlozorov, the building where my mother resided before she got married. Indeed, it was Pnina’s son, Amos, who suggested that my parents name me Nili. They liked the sound of the name, unaware of the fact that “Nili” was the name of an underground Zionist group during World War I. As children, we used to visit my mother’s former neighbor quite often, and we knew her well.

In April 1933 my mother arrived in Palestine from Chernovitz, Bukovina, and settled in Tel Aviv, where she had relatives. When her ship neared the Jaffa port, she told me, the “English”—as she called them—boarded, gathered all the passengers in the ship’s hall, and interrogated them one by one. In accordance with the British Mandate’s policy of limiting Jewish immigration, they decreed that most of the passengers had to return to their country of origin. My mother, who had prepared for this interview ahead of time, pretended to be a tourist: she carried with her only one small suitcase; she had a lot of money to show; and, most important, she had the name of the family of “engineer Gruenfeld,” the well-known industrialist, as her supposed hosts. The British were convinced that my mother was indeed only coming for a visit and permitted her to board one of the little boats that awaited the lucky few allowed to come ashore. The ship was ordered to go back to Europe with the rest of the passengers. Upon hearing this, some of them committed suicide by jumping off the deck, while others began a hunger strike. Eventually, the British caved, allowed the ship to anchor in Palestine, and issued official entry certificates to the survivors—it was 1933, and the British were still susceptible to public pressure. On the streets of Tel Aviv my mother would sometimes run into the other passengers. “Some would not say ‘hello’ to me, thinking I was a traitor. The others would say, ‘See? I have a true certificate,’” she recalled. The Gruenfeld house became a second home to her, and the children, Karin and Eli, dear to her heart. Even after we, her own children, were born, she always carried a small photograph of a girl with a bob haircut and a serious, blond two-year-old boy, each wearing a rain cape.

During World War II, when Haifa became the target of air raids starting in 1940, many left the city. My fearless mother, however, decided to move there because she thought, accurately, that the emptying city would offer good job opportunities. When she came from Tel Aviv, she rented a room on the roof at 26 Arlozorov, which stood slightly above the street’s sharp curve. It was not far from the Itzkovitz House, whose tenants had by then moved to a different neighborhood, and almost across the street from the Struck House, whose tenants tenaciously remained. At that time the artist’s home was crowded not only with visitors but also with refugees from Germany, whom Struck hosted in the various rooms of his big house, including his studio, workshop, and the basement.

A few days after my mother moved to Haifa she became so ill she could not get out of bed. By chance, one of the building’s tenants went to the roof to hang her laundry and noticed my mother lying in her room with the door slightly ajar for air. She greeted her, then disappeared. A short while later, however, she returned. The description of the tray that Pnina brought to my mother that day was repeated in my mother’s stories in many variations, but it was always set elegantly, with porcelain dishes arranged on a white, ironed cloth napkin; a soft-boiled egg; and dark bread. The striking Pnina looked a bit like the first lady of Hebrew theater, Hannah Rovina—her jet-black hair gathered behind her head in a bun, her features chiseled, and her lips always painted red. Even though Pnina was affiliated with the right-wing, nationalist Herut movement and my mother was a socialist, they remained lifelong friends.

After my mother married my father, she moved from Arlozorov Street into his small apartment on the western end of Hadar HaCarmel. In 1954 all four of us, my parents, my younger brother, and I, moved back east, to the house on 85 Herzl Street, near Arlozorov and Ge’ula. Our new apartment was lovely and airy and seemed as if it had been made just for us.

At the entrance to the apartment is a long, long corridor. You can roll a ball from one end to the other; you can run races or even ride down it on the small bike of a four-year-old. No wonder the poor neighbor who lives underneath us is always angry. “Gadi runs through the rooms and down the long corridor and calls out ‘Ima! Where are you?’ Nilinka is happy too; she says, ‘We have such pure air to breathe!’ . . . It is also very close to the store,” my father wrote in a letter from October 1954 to a cousin in New York, who would give it to me thirty years later.

To the right of the corridor near the entrance of the apartment, the kitchen opened up. This is where we ate on weekdays, did our homework, and chatted over coffee. This is also where my mother used to quiz me on lists of difficult words when I prepared for spelling tests. Adjacent to the kitchen was a small balcony from whose northern corner we could see the sea.

From a small alcove farther down the corridor, two doors opened to the washroom and the bathroom. Our bathroom: a kerosene boiler and a small, blue flame that heats water for a shower. I sit on the edge of the tub and follow the ritual of my father’s daily shave. With a soft brush, he spreads a mask of thick, white foam over his face. Only his forehead; his soft, red lips; and his kind eyes peek out from the white mask of soapsuds. Afterward, with skilled magician’s fingers, he slowly and meticulously uncovers his features from under the mask, shaving his face closely with a straight blade. Sometimes he cuts himself and then wipes the bloody scratch with a purple stick. And on Thursdays we fill the bathtub with water for the two fish we bought from the large pool of carp at the store belonging to our neighbors, the Schechters. Mrs. Schechter hits their heads so they will stay calm until they arrive at our tub. And in the bathroom, for the remainder of the evening, we caress their smooth, slippery backs. The next morning my father kills them. Their entrails and the blood are on the marble counter in the kitchen. I peek in and run away with horror. And at the festive Friday night meal my mother serves the gefilte fish she has cooked, and I refuse to eat it.

On the left side of the corridor, doors opened into two large rooms, the children’s room and my parents’ bedroom. Each one had a large casement window with wooden shutters and little metal people as shutter stoppers. Our room was painted a very pale green with a dark blue stencil pattern that I chose, which circled the room just under the molding with blue palm trees, blue balls, and blue children, all of whom kept me company every evening until I fell asleep.

At the first light of dawn, long before we get up for school, we hear Mr. Drimer feeding the pigeons from his balcony as they coo blissfully. Before the pigeons, when it is still dark, we can hear the low growl of the buses on Herzl Street, even though our apartment is in the back of the building. The humming of the buses is our rooster crow. When they begin, that means it is five in the morning, and I usually fall back asleep. My mother comes to wake us up at seven o’clock. “You must get up, wash up, get dressed, and pack your schoolbag,” and music from the radio is playing loudly, urging us to hurry. A moment for a sip of coffee with milk and a bite of black bread with margarine, trying to reach school one moment before the bell. On my wrist hangs a hand-sewn, drawstring bag holding a wrapped sandwich and a folded, ironed cloth napkin with wide gold edging.

We entered my parents’ bedroom only on rare occasions—on Hanukkah, for example, when we lit candles in the menorah that was placed on the sewing machine near the window, or when the seamstress would come for an entire day of taking measurements and cutting and chatting. As in the other rooms, the windows opened wide and tall, and the treetops peered in at us through them. My mother loved the cool cross-breezes that blew through the house.

At the end of the corridor, facing the entrance, was the capacious living room, which always welcomed me with open arms. There, there was the radio, an old, wooden box that sat on the top shelf of a low bookcase. We were all avid radio listeners; there was The Child’s Corner every day at five in the afternoon: “Hello children, this is me, Esther, talking to you.” At seven in the morning, the program Classical and Light played throughout the house as we got ready. Sometimes Gadi listened to Arabic music; on Saturdays Hebrew Songs and Folk Songs, then the festive Shabbat lunch, and at two o’clock my father, a glass of black coffee in his hand and a sugar cube between his teeth, listened to the weekly program of cantorial music—the cantor Yossele Rosenblatt, the Melavsky family, or Moishe Oysher. My mother used to complain that they never played the greatest of them all, Joseph Schmidt, the famous opera singer whom she remembered from Chernovitz and whom she was privileged to meet in the 1930s when he visited Tel Aviv.

On the wall above the radio was a single print by Chagall of a Jew, phylacteries on his arm, and behind his back, a snowy landscape. On the bookcases sat a few of the many children’s books that Uncle Chaim had brought us from his bookstore: the pale blue–bound Greek Myths for Children and Norse Myths for Children with their gold lettering, as well as Treasure Island and stories about inventors and their inventions. But most of the books were in German—among them, my father’s Bible, with a Hebrew column and a parallel German column in ornate gothic letters. In third grade I began to read it, seated on the rug beneath the large, heavy dining room table in the middle of the room, the table on which we dined only on Friday nights, Shabbat, and holidays. We each sat in our predetermined seat: my mother on the chair closest to the kitchen, my father across from her, Gadi on the east side, and I on the west. Between courses we would run to sit on our father’s lap, and he would whisper to us to go to our mother. On the eve of Passover, the table would open and become longer, and, miraculously, a Passover seder would spread over it. On that day the corridor had a special role to fill. Gadi and I had to run the whole length of it to the front door to open it for Elijah the Prophet. For some reason the hallway always seemed very dark, and it was scary to run all the way to the door and open it a crack for Elijah while the grownups were standing and reciting “Pour Thy Wrath.” After that they usually put us to bed, but we could still hear a little bit of the singing wafting in from the living room.

But my favorite place in our house was the large terrace, a generous space that spanned almost the entire width of the building. Reading his letter thirty years later, I learned my father shared my love for it: “From our terrace, you see the end of the sea and the bay. What a wonderful view. And it is quiet all around and now we begin living anew.” Because our apartment was on the top floor of the northern wing, which faced the bay, the nautical landscape was inextricably linked to it. The railing was high, but even at age six I could look over it to see the curve of the bay and the purple mountains on the other side of it. There was Acre, we knew, and Mount Hermon, and there was Lebanon.

Years later, standing in front of one of Struck’s aquarelles, I realized that the artist’s roof stood along the same line of sight as our terrace, just a bit higher on the mountain—his view was from the exact same angle as mine. He too had been drawn to this magical vista, and, being an artist, he thought it was the quintessential subject for drawing and tried to replicate its colors in his paintings.69 When I learned this, my heart went out to this man who so loved the view I cherished.

To the right of our terrace, in the east, lay the green hills of Neve Sha’anan and a little to the north the industrial area, ruled by Haifa’s “giant yogurt containers”—the refineries that rise there. But across from us, really close, so very close, was the sea. Sometimes it was blue to the point of pain, endlessly pure and devoid of ships; sometimes gray. In the mornings (I always ran to the terrace when I woke up), the fog used to cover it and were it not for the horns of ships announcing their existence, the bay itself might have disappeared. On Shabbat mornings sailboats glided in red, yellow, and white.

And in New York Kronzon’s stories reveal that he, like me, belongs to the fraternity of those who grew up on the large terraces on the northern slope of the Carmel and carry that view wherever they go: flat-roofed white houses, dotted green treetops, the bay, and the ships.

Uncle Abrasha walked around the terrace, looking at the ships in the port. . . . Suddenly I remembered that Mother always said that Haifa is the most beautiful city in the world, so that is what I said to my uncle. He looked at me . . . and asked . . . if I’d seen all the cities of the world. I said that I hadn’t, and he said, “So how can you say that if you haven’t seen them?”70

The recurring mentions of the terrace in Kronzon’s stories are a melody that accompanies the history of his family, its joys and disappointments, its lives and deaths—on a warm Shabbat morning in the middle of the winter: “mother sits on the terrace, closing her eyes . . . and enjoys herself.”71 And on special days, like the narrator’s bar mitzvah, “sixty people crowded onto the terrace.”72 When Marcus-Ron, “mother’s employer” at the conservatory, came for a Friday night meal, the family took down the “Czech china service” in honor of the occasion, and they “brought the table out of the dining room onto the large terrace.” But, unfortunately, when the honored guest began belting out the Kiddush, the Friday night blessing, the narrator’s mother could not hold back and burst into laughter that offended him: “Marcus-Ron stands . . . his face to the sea and the Carmel at his back . . . his mouth agape . . . and from the depths of his chest bursts a powerful, ear-deafening, glorious roar that rolls over all of Hadar HaCarmel all the way to the bay: ‘Yom hashishi.’”73 The large terrace becomes an active participant in the scene because only against the backdrop of this epic landscape could the catastrophe—his mother’s uncontrollable laughter—have reached its mythic proportions.

In another story, when the child narrator suffers a major blow, he turns to the terrace, as if he can truly unload his sorrow only while facing this landscape: “I walked into the apartment and went out to the big terrace. I leaned on the railing, looked out at the ships in the bay of Haifa, and cried.”74 The terrace, however, plays a part in daily routines as well as climactic moments. The narrator’s father regularly tutors math there. As one summer day wanes in yet another story, “he sits in a mesh undershirt on the large terrace and explains. . . . I lie quietly on the sofa and listen. I’m small and don’t understand. . . . Over the port . . . from the sea a cool breeze starts blowing.”75

This scene recurs at least twice more, but its subject has become the father’s final tutoring session. Here the words “the large terrace” turn into the sounds of a requiem. In one story: “My father died on a Friday morning at 10:45 while tutoring a high school girl in math, on the large terrace of our apartment on Ge’ula Street.”76 And in another: “He died in the middle of a private lesson in math, on the large terrace.”77 The final farewell to the house on 21 Ge’ula Street also takes place against the backdrop of the same landscape, when the visitors who come during the shiva gather on the large terrace for the last time.

Haifa’s terraces, then, played many roles. In our house on 85 Herzl Street, we could look out over the roofs of all the houses below us. Across from us lived my friend Ester Peleg, whose apartment was so close that I could call out to her—very loudly—“Ester! Ester!”—and ask about homework (in the 1950s, almost no one had a phone). On one rooftop terrace we could see a man, working day and night, his table loaded with books. Years later I would meet him again. It was Yitzhak Ring, my high school Bible teacher.

On Sukkot Gadi and I built a sukkah on the terrace under the blue table and decorated it with paper chains. Nearby trees sometimes dipped to brush the railing, dewdrops swinging on their leaves on spring mornings, the wind rustling through them. When it rained, we stood near the railing, close enough to feel the light touch of the water sprinkling on our faces but far enough that we didn’t get really wet.

On summer evenings our family would eat dinner there, caressed by the moon’s rays, surrounded by the lights of the balconies of nearby houses and, over the dark waters of the bay, the sparkles from the sailboats and ships and the breakwater. A gentle breeze would blow through the treetops that circled our house—tall, almost as tall as us as we stood there, but never blocking the view. When autumn came and the school year started, I would prepare arithmetic questions that I supposedly could not solve without my father’s help in order to win a few more minutes with him before going to bed. Then I would join my parents’ quiet supper and steal a slice of bliss: only the three of us, as “little children” like Gadi had to be in bed already. The table was covered with a tablecloth, and an arc of lights etched the curved line of the bay at night.

Every Friday my father would come home early from the store, and we would listen for his footsteps on the stairs and run to him. For each of us, he would bring a little bag from the sweetshop that opened in the front of our building shortly after we moved in. Beneath the glass that covered the display table that stretched all along the storefront lay the treasures. The chocolate we loved the most we called “tree trunk,” because that’s what it resembled. Chunks of lop-ended chocolate, three centimeters long—each one looked like an ancient tree trunk, but when it reached our mouths, it would melt and dissolve and its texture was as pleasurable as its taste, the taste of milk chocolate Fridays.

Shortly after the beginning of third grade, we had drills to prepare for a possible war: leave the classroom quickly and run to the shelter in an orderly fashion, without mischief. It was 1956, the days before the Sinai campaign. As in my father’s store, the windows in the stores on the ground floor of 85 Herzl Street and all the glass panes of the apartment windows were crisscrossed with a plaid pattern of masking tape to prevent them from shattering in the event of bombings. At night a “blackout” was imposed, and we shrouded these glass panes with blankets so no light could seep through. There was no bomb shelter in our building, so when the sirens sounded, we were to go down to the lowest floor and sit in a windowless space.

My mother sweeps the floor of the corridor. Next to the front door she leans on the mop; her head is lowered. Ima, what happened? You’re crying. Eli fell in battle. Eli? Yes, Eli Gruenfeld, the blond kid with the rain cape from the picture. But maybe it’s not him. Maybe you’re wrong. Let me go down to Kahanovitch to buy the newspaper. And there, among the two lines of the young faces that were printed in black and white in two vertical rows on the sides of the front page, was the face and beneath it, the name: Sergeant Shmuel (Eli) Gruenfeld, nineteen years old. His name is Shmuel, not Eli. Ima, don’t cry. Maybe it’s somebody else.

I don’t recall the sound of the siren, but I vividly remember going down the dark staircase to the Kligers’ apartment. I never visited them before or after, but on the night of October 31, 1956, all the house’s tenants sat there, in the Kligers’ corridor. We crowded on the floor or on low seats and waited for the all clear. My father did not join us. Only Gadi and I were there with my mother. Afterward, I learned that my father had insisted on watching the events that unfolded in the bay. He sat on our terrace and observed the Egyptian warship Ibrahim El-Awal shell the city.78 Then a French destroyer, anchored in the port, opened fire and the Israeli navy overcame the ship as it tried to retreat out of the territorial waters. In the days after the war, the destroyer was renamed Haifa, and, along with many of the children and residents of the city, we went down to the port to see it from the inside. Everybody sang, “It is no legend, my friends, / And not a fleeting dream / Behold, in front of Mount Sinai / the bush is burning again.” I will never forget that President Eisenhower stopped food deliveries to Israel to pressure the Israeli government to retreat from the Sinai Peninsula.79 Suddenly, the salty American butter, which I loved, disappeared from grocery store shelves, and white sugar was nowhere to be found.

But the war was an aberration. Usually, the routine of our lives on 85 Herzl was sweet. Our apartment’s proximity to the store meant that my father could now come home every day for a long lunch break, eat with us, then grab a short nap, during which we had to be quiet. As my home was also close to the school, it became a favorite meeting place for friends to do homework together in the children’s room or on the large terrace or to play in the generous space provided by the apartment. We were not allowed on the busy Herzl Street, but sometimes we went down to play in the small yard next to the house. At its entrance stood a pomegranate tree, often dotted with red flowers or fruits, and on its other side was a large fig tree that never gave fruit, but in the winter stood bare. The fig tree is one of the only trees that loses its leaves in the Mediterranean winter. So my pride knew no bounds, of course, when hamora Sara took us all to see my fig tree in third grade when we learned about autumn and how some trees lost their leaves. Friday afternoons and Saturdays continued to be the climax of the week. My father was home. All of us together on Sabbath eve, challah and Kiddush. On Saturday afternoons, after a leisurely schlafstunde, my parents’ acquaintances would stop by. On the table in the living room the blue-and-white porcelain dishes appeared, a thin gold line around their edges, and a vain porcelain coffeepot—for coffee and cake and chatting and laughing, all in German.

On gray weekdays my father used to sit for hours in the living room at night, alone, making calculations. He had long rectangular ledgers with red margins, which he filled with numbers and dates. Was it these ledgers or the frequent notices from the government that killed him in the end? My parents protected us from the horrors of the overly heavy taxes imposed on them as store owners, but the syllables of masahakhnasa (income tax) always made me shudder, even though I did not understand them.80

My father had brown-rimmed reading glasses and wavy hair, combed backward, all black and silver threads. After work he would soak his tired feet in the white enameled basin, filled with piping hot water from the kitchen teakettle. I did not understand his exhaustion and fatigue then. I was only happy that he was home.