H ector Mendoza wore a Rolex on his wrist to flaunt the success of his various business ventures. Although he’d lived and worked in Los Angeles for decades and was an American citizen, he hailed from the Philippines originally and cultivated influential government contacts. In the winter of 2001, he got a phone call from one of his Filipino associates. It was time.

Mendoza checked into a hotel in Manila. A few days later, he was gambling in a coin-toss game and was stabbed in a dispute over winnings. He bled out in a dusty park lined with doorless shacks and mangy dogs prowling for scraps.

The body was brought to a local morgue. His wife flew in from LA and identified his corpse. She organized the funeral, presided over by a priest. Mrs. Mendoza had her picture taken next to the open casket but covered her face with her hands, too distraught to look at the body inside, which was cremated and shipped back to the United States immediately after the service.

Later that evening, Mrs. Mendoza met her husband for dinner in a Manila restaurant.

SOMEONE DIED THAT DAY, but it wasn’t Hector Mendoza. As Steve Rambam, who investigated the death, explains, “When I went to the tiny little restaurant where witnesses said they saw Mendoza get stabbed and showed them a picture of him, they all laughed! The person who was actually killed was the local drunk. His idea of a good day was scoring a bottle of rotgut whisky, playing a couple of twenty-five-cent dice games, and passing out in the bushes.” Rambam arrived in the Southeast Asian country to conduct his investigation on behalf of one of the half dozen life insurance companies that had questioned the veracity of Hector’s death when Mrs. Mendoza attempted to cash in six policies her husband had bought recently—worth several million dollars in all. Rambam has been investigating fraudulent death claims like Mendoza’s for three decades now, so he’s inured to the macabre theatrics. But he still can’t resist snickering when he tells the story.

Rambam is an elite private investigator. A big part of his business involves contracting for life insurance companies. When fishy death claims that exceed a certain amount get filed (think seven figures), Rambam hops aboard a plane, treks out to the scene of the crime, and finds where the bodies are not buried. His job is not so much proving that a claimant is alive as it is demonstrating that the person is not dead.

He’s telling me the Mendoza story in the pressroom of the Marriott Marquis in Times Square, during the annual Open Web Application Security Conference. Earlier that day, Rambam was on a panel and dispensed some stern words to his audience: privacy is forever dead and we should get over it. In this world of hackers and security experts, he’s a bit of a celebrity. As we were grabbing drinks at the bar, a bespectacled fellow recognized him. Rambam stands out a bit in this crowd, or “nerd convention” (his phrase), because he is over six feet tall and looks as if he wasn’t dressed by his mother. But it’s not just his appearance.

A few years back, FBI agents physically removed Rambam from the HOPE (Hackers On Planet Earth) Conference in Midtown Manhattan for exposing their malfeasance in a case that involved an impostor claiming to be the prince of Austria. He’s now the star of his own TV show entitled Nowhere to Hide , a reenactment-heavy drama that re-creates his most famous cases. The show’s fan base is mainly middle-aged women. He inspired a character named Rambam in writer Kinky Friedman’s Masters of Crime series. Whereas Frank Ahearn is the rough-and-tumble Bronx boy, Steve Rambam flies all over the world in a tailored suit, keynoting conferences like this one. His face is arresting, he lumbers more than he walks, and he has massive hands like paddles. He seems to have been teleported from another era. Frank can find anyone with charm and a telephone, but Steve pounds the pavement in overseas investigations, going undercover, working with local law enforcement. Frank told me that if you faked your death and tried to collect on an insurance policy, there are guys who get paid to check you out. Steve is one of those guys.

Back in the Marriott Marquis, I’m trying to get a handle on what, exactly, Steve is telling me about Mendoza. How does a dead homeless guy have anything to do with the rich American businessman with an ostentatious watch?

“Mendoza was actually highly organized, because he worked with a very senior administrator in the local government in the Philippines,” Rambam explains. “He’d been planning to fake his death and collect on a policy for a while. They waited until some local guy died of violence, not old age. And the guy had to fit Mendoza’s physical description—a person of roughly the same height and weight—and then the family could go to the local morgue and claim the body. The wife came in and identified the drunk as her husband. But the body was always this homeless guy’s.” Mendoza had claimed the knife attack as his own.

Without a death certificate, insurance companies wait seven years to release money, and you need a body in order to get the paperwork. So Mendoza procured a corpse to expedite the process. For life insurance fraud, this peculiar practice is not exactly out of the ordinary. I’d heard rumors of so-called black market morgues where you can buy a body, cheap and easy, for your pseudocidal intentions. In 1986, Equifax Insurance spokesman John Hall told the Wall Street Journal , “In one Southeast Asian country, there’s a private morgue that picks up dead derelicts, freezes the bodies, and sells them for insurance purposes.” Based on Rambam’s tale, it sounded as if mismatching bodies and identities is still a flourishing business.

Frank had reiterated again and again that faking your death was a stupid thing to do because, compared with simply disappearing, it’s a whole lot easier to get caught. But since collecting a payout is one of the most obvious and frequent reasons people fake their deaths—at least as evidenced by the six o’clock news—I wanted to know what kind of chase a company will deploy. What are the big considerations to take into account if you want to get rich and not die trying? While Frank helps people go off the grid and can skip trace from behind a desk, I wanted to know who gets on the plane and digs up the bodies. And, of course, how do people get themselves busted?

And black market morgues?! Really?

Steve says it’s not even that the morgues are illegal: “You can just go into any city morgue in almost any developing country, ask to see the unclaimed bodies, and cry, ‘Oh, it’s poor Uncle Marco!’ They’ll be happy to get a body off their hands.”

So how would a fraudster like Mendoza, who wants to go to great lengths to set up a realistic fraud, obtain a body?

“A private morgue picks up any body that’s not claimed,” Steve says. “They take custody of this body, and they roll the dice. If the family comes and claims the body, obviously they charge storage. It’s like towing a car. If no one comes and claims the body, it’s their problem to cremate and bury it. I was in the Philippines a few months ago, and it’s still going on. It’s ridiculous,” he says.

I ask how much it would cost to commit a death fraud in the Philippines, like Mendoza did. The figure is less than I would have imagined.

“I think everything, from soup to nuts, including your body, is about five thousand dollars,” he says.

“Including a look-alike corpse?” I ask.

“You’re doing them a favor! You’re paying for the storage charges, and you’re paying for cremation. They’re not building you a body like Frankenstein in a lab! Okeydokey, then! Here’s your body! Now they’ve got an empty slab they can refill. Their investment has come through.”

Though attempting to pass off a deceased stranger’s body as your own does add a flourish of grim verisimilitude, it turns out that acquiring a cadaver is usually not necessary to fake your death for an insurance payout. Death fraud, in most instances, is conducted primarily with documents. In Mendoza’s case, his paperwork—his death certificate, and the accompanying police and coroner’s reports—all checked out. “All the documents were legitimate,” Rambam explains, “because they were obtained by the governor of the province.” All of the seals, watermarks, and signatures were authentic.

Rambam brought his guys to the local Quezon City Scene of the Crime Operatives (SOCO) Unit, the Filipino equivalent of CSI, and showed the crime scene investigators Mendoza’s passport photo. “They all said that the photo didn’t match the body that came in,” he says. “So I interviewed his wife, and she broke.” Mrs. Mendoza recalled this interview in her grand jury testimony four and a half years after the crime took place:

INTERVIEWER: What did Steve Rambam ask you?

MRS. MENDOZA: That he needed to talk to me in regard to Hector.

INTERVIEWER: What did you tell him?

MRS. MENDOZA: I told him the truth.

INTERVIEWER: And the truth is?

MRS. MENDOZA: That Hector Mendoza is alive.

Mendoza was hiding out up in the north of the country, and Steve spoke with a few of his co-conspirators. “The problem Mendoza didn’t anticipate is that everyone had gotten sick of him. He was a real hustler, always into some kind of monkey business,” he says. All of the local guys with whom Mendoza had colluded were eager to turn him in. They offered to deliver him to Rambam on a plane to Hawaii for $10,000, whether he wanted to be on the plane or not. They could get rid of their problem and get paid at the same time. The fact that these double-dipping cronies offered to give Mendoza up for cold, hard cash illustrates just how difficult it can be to find trusted co-conspirators to help you fake your death. The deceased, unfortunately, can’t collect without the right people to file on his or her behalf.

The investigation looked like it was going to come to a triumphant close: once on American soil, authorities could arrest Mendoza for a huge life insurance fraud. Rambam had even received the green light from the insurance company to collaborate with Mendoza’s associates, whom he had managed to turn. He told them that they would get their money once they got Mendoza on the plane. The deal was in motion. But then the insurance company panicked and backed out at the last second. “They called me and said they spoke with their attorney and that this was kidnapping.” Rambam tried to tell them that it was actually police ejecting him from the country; he would have paid them a finder’s fee. “They said, ‘We don’t care how you package it, we’re not going to do it.’ ” To Steve’s knowledge, Mendoza is still in the Philippines, with an American warrant out for his arrest.

AS WITH FRANK, MEETING up with Steve Rambam in the flesh took a lot of time and massaging. I’d first encountered Rambam’s name cited in a 1997 New York Times article headlined “Fake Deaths Abroad Are a Growing Problem for Insurers.” Then I found the delightfully analog clip-art-spangled website for Pallorium, the investigation agency he founded thirty years ago. The number listed goes directly to voice mail, and he calls you back at his convenience, which I consider a boss move. After a summer and fall of competing with Steve’s hellish travel schedule, we finally organized a rendezvous when he phoned me from a blocked number and arranged the meet in military time.

I found him on a drizzly afternoon just before Christmas in front of the New York Public Library on Madison Avenue. He’d gone there to look up some files for a case he was working. He had dressed the part, in a tweed jacket with elbow patches over a sweater and tie. We walked awkwardly in the rain, and I kept bumping him with my umbrella. We popped into several establishments, which he deemed either too loud or too quiet, until we happened upon one that was just right. We took our seats and had a terse exchange in which he asked me sarcastically which sorority I pledged in college. Despite my pink dress, high ponytail, and the unfortunate Valley Girl twang I picked up God knows where (marathon viewings of The Hills , methinks), this lady neither rushed nor pledged. Taking offense, I rebuffed him with a testy “Guess again!” We spent several tense moments in near silence, punctuated by his commentary on the place setting before him—the tablecloth was filthy, the water glasses smudged—until, mercifully, the waitress came and took our order, and I proceeded to get day drunk on Chardonnay as Steve sipped his Guinness. Finally, lubricated, he asked me to explain myself and my interest in pseudocide again, and, in a fit of disappointment, guffawed, “You’re writing a book on what ?”

He would reprise this question to me over the next few years, and chastise me that it wasn’t finished, and compare my publishing record with the many texts he’s penned on British spies, practical privacy tips, and P. T. Barnum. The whimsical daydreams that Frank and I shared about the fantasy of disappearance and life’s incompatibility with our desires didn’t register with Steve. Instead, he’d lift one of his ample eyebrows in a doleful, pitying look that I became accustomed to absorbing and eventually relished receiving. If I got the lift of an eyebrow, it meant I was onto something.

Rambam describes himself as a “moving target.” He is rarely in his home base of Brooklyn for longer than a handful of days at a time. The reason he is a moving target is because Pallorium specializes in overseas investigations work. By his description, his job is as hard as a spy’s. “I’ll get sent somewhere I’ve never been before, and I have to build up an intelligence infrastructure, develop contacts, and defeat local people. I have to do it all out in the open, and in a finite amount of time. I’ve got a few weeks to break a very sophisticated crime in a foreign country where I don’t speak the language.” James Quiggle of the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud says, “There is a certain Indiana Jones aspect to unraveling suspicious death claims in a foreign country.” Richard Marquez, Rambam’s longtime friend and colleague and the head of the Texas-based Diligence International Group, which describes itself as “global intelligence experts,” believes that “Steve is one of a handful of people in the world who can do what he does.” Marquez, too, has been at the helm of hundreds of death fraud investigations, and the two have worked dozens together. But where Rambam can be prickly and sarcastic, Marquez is easygoing and warm.

But what sets Rambam apart in the world of high-profile sleuthing is his tenacity. While Rambam is out in the far-flung corners of the world, working with local law enforcement, interviewing witnesses, and going undercover, a big part of the job is simply not going home when everybody else does. Beyond his brazen attitude and knack for subterfuge, Rambam credits his stunning success rate to sheer hardheadedness: “You know that old Woody Allen joke that ninety percent of life is showing up? Now, I’m not a Woody Allen fan. He’s a lefty and he married his own daughter. But ninety percent of investigating is showing up. What most investigators don’t realize is that just showing up counts for a lot. Just go and start investigating. These cases are daunting. Most people say, ‘Oh my God! This case is in the Philippines! They have snakes there! And people disappear! And I’m never gonna find anything! And there’s gonna be a language problem!’ You can go on like that and paralyze yourself. But there’s a real simple solution. Get on a plane and go to the Philippines. Start knocking on doors. Just go! Do it! You knocked on a door and you didn’t find anything? Knock on another door. Then knock on another door. And even if you fail for ten days straight, on the eleventh day, you’ll get something. Always.”

Rambam’s work is propelled by an ingrained sense of justice. TV journalist Mike Wallace introduced him on 60 Minutes in 1997, saying, “The traditional cold calm of Canada has been shattered by a meddling American.” As a personal project, Steve had located former Nazis living in Canada by scoring their information from survivor groups and documentation centers in Germany—he even “scammed some” out of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, the Jewish human rights organization. From a list of two hundred names, he winnowed it down to the most outrageous. “There was one Ukrainian SS guy who specialized in the murder of children. So he went on the list,” Rambam tells me with a sinister grin.

“I said, ‘I’m Salvatore Romano’—I didn’t want them to know I’m Jewish, and I had a real Zairian passport made with that identity—‘and I’m a professor at St. Paul’s University of the Americas.’ That’s a bogus university, but I set it up as a business in Belize and made business cards and a sweatshirt. And then I’d say, ‘I’m writing my thesis on blah blah blah,’ until their eyes rolled back in their heads, and ‘I’d like to talk to you about your wartime experiences.’ And they would talk to me. A lot of them detailed the crimes they had committed, totally openly.”

And what other kinds of jobs does Rambam handle, apart from Nazi hunting and surprising the undead?

“I do a lot of fugitive cases, a lot of difficult-to-find witnesses. Luis goes back to Guatemala after witnessing a shooting, I go find him. I do everything.”

“What are your favorite kinds of cases?” I ask him.

“Whatever pays a lot.”

And get paid a lot he does. Subcontracting for big American firms, when he is working a life insurance case somewhere such as India, Nigeria, or the Philippines (the same countries with the rickety governments and capricious extradition policies of my off-the-grid fantasies), he charges in the neighborhood of $1,500 per day plus expenses to track people. He always finds his guy.

It’s oddly consistent work because there is often some industrious person somewhere who tries to die and get rich in his afterlife. When I first reached out to Richard Marquez, Rambam’s colleague, he quipped in an email about the frequency of his jobs: “Our company specializes in foreign death fraud, and the problem is alive and well—excuse the pun.” Steve told me that he personally takes on an average of twenty death fraud cases per year. In the context of all insurance fraud, however, death fraud is extremely rare, though exact statistics are hard to come by because of companies’ tight-lipped policies. James Quiggle, whose organization documents and analyzes the panoply of insurance fraud—from Medicare to life to fire to flood—says, “Staged death is an outlier. I’d say it makes up less than one percent of the cases we see.”

A typical life insurance fraud of the variety that Rambam and Marquez encounter might look something like this: You are summering back home in a bucolic corner of your native Mongolia. You die in a tragic oxen charging. A shepherd witnesses your pummeling and impalement and slow perishing on the side of the road. He sends for a doctor, who immediately pronounces you dead. The village holds a big country funeral, mourners weep over your coffin, and you are buried within a few days.

Your wife files to collect life insurance. She submits all the requisite paperwork: a death certificate, an autopsy report, a police report detailing your violent bovine disemboweling, and even photos and video from the funeral. But a claims examiner at the insurance company flags the application, delaying a payout. “Claims examiners know when they see a fraud,” Rambam says. “They have a sixth sense.” So when the policy is over a certain amount (they’re not paying Rambam thousands a day for a piddly policy) and the company harbors suspicions (if, for example, you increased your coverage just recently), the company calls in their guy. Rambam gets on the plane, treks out to the obscure Mongolian village, interviews the shepherd, and takes statements from local police. If necessary, he will dig up the coffin. One time he found rocks inside.

What kind of person is cut out for this work? Rambam grew up in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. “I grew up with a zillion different types of people,” he recalls. “I was a guest in every kid’s house: Chinese, Arab, every Caribbean nation you can think of. I had the most freakish bar mitzvah you’ve ever seen.” He learned to live by an old-school code of loyalty and integrity: “You give your word, and that’s it. There’s no renegotiating in Flatbush.”

In between his hardscrabble New York days and starting Pallorium thirty years ago, there’s a long, cloudy gap in his biography, which he won’t go into in great detail. Rambam will admit to earning his “sneaky training” working for a government locating missing persons. He also realizes the serendipity of entering the profession when he did. “I came into the investigative field when it was the real deal,” he recalls. “You weren’t just tapping on the computer. You had to go out and knock on doors. You had to learn film cameras, so you had to understand the light. You understood how to interview people, how to position yourself in the chair.” He has led over five hundred overseas death fraud investigations. “Everyone has been either extremely easy or extremely difficult to find,” Rambam says. “There’s no in-between.”

EVERY TIME I MET Rambam, he tried to discourage my civilian’s fascination with faking death. He has dealt with too many incompetents to be captivated by its allure anymore. “You can separate yourself from the world without faking your death,” Rambam explains. “You need a real reason to fake your death: either a nefarious reason or exigent circumstances. I’ve never found a case where somebody faked their death for an acceptable reason.” But more than just finding an acceptable reason (and I still maintain that student loan debt and ennui are perfectly valid), Rambam echoes Frank’s misgivings about the effectiveness of such a complicated plan.

“Faking your death almost never works,” he says. “You have to be devoted to staying disappeared like it’s your job. It takes a lot of effort and aggravation. Everybody I’ve caught on life insurance fraud, I tell them, ‘If you had put this type of effort, money, and dedication into your life as a law-abiding citizen, you would’ve made just as much money.’ ”

But how is the tedium of slogging through a dismal law-abiding existence to compete with the siren call of total freedom? And the temptation of a multimillion-dollar payout on your little life to underwrite all your yardstick margaritas, novelty T-shirts, and cabana boys in a lazy beachside town? I had yet to be convinced.

The people that Rambam and Marquez investigate typically fit a certain profile: they are foreign-born nationals who return to their native country and meet an untimely end. This is a different bunch from the white middle-class guys who fake their deaths Stateside, such as Sam Israel. And naturalized US citizens like Mendoza returning home and meeting a tragic death rarely make the news. “Faked deaths on foreign soil are very common in the overall sliver of faked deaths,” Quiggle says. “A third-world country is far easier to negotiate, and the ‘death’ is far easier to set up in a foreign country than it is in the States. You have low-paid bureaucrats you can bribe. In societies where people are very poor and need money, a fraud can be seen as a desirable way to feed your family. Fraud can be considered a legitimate enterprise,” he explains. Like Mendoza, the fraudsters will have strong local connections in their country of origin and know whose palms to grease and which fixers to charm in order to score the requisite documents. The countries in which the investigators pound pavement (or dirt roads) change often and go through cycles, but lately there has been an uptick in death fraud originating in the Philippines, Mexico, India, and China. “You have a lot of expats from these countries, people who are traveling back and forth,” Rambam explains. “And you have a robust, centuries-old tradition of corruption.” Typically, the accident gets staged in the boonies, and fraudsters don’t anticipate the lengths to which a company will go to avoid paying out a hefty policy. “A lot of people think that once the insurance company has the documentation, they will just pay the claim,” Marquez says. “And since a lot of these people are from remote towns, they think no one will ever bother to send anybody to investigate.”

Death fraud can be big business in many of these obscure locales, not just for the claimant but also for the local economy. A small but thriving infrastructure exists to assist you in your tragic accident. A witness’s testimony is for sale, as is a doctor’s signature on your death certificate. In countries such as Haiti and Nigeria, enterprising middlemen streamline the operation for you. There you can buy what is known in the biz as a “death kit.” Marquez elaborates what you can get for a few hundred bucks: “A death kit includes a copy of the fake death certificate, a burial permit, photographs of the actual burial plot. They will often make a video of the funeral Mass, of people crying and wailing, and the funeral procession down the street. They are basically performing the ceremony.” Rambam sums it up: “A death kit is basically, ‘Step right up and buy your all-inclusive fraud package!’ It’s a shell corporation for fraud.”

How much you are willing to pay will sometimes determine the quality of the amateur dramatics at your funeral, such as how many mourners you can cast. Marquez remembers one video from a Nigerian case: “They had the body lying in the middle of the bed, and mourners were chanting in a circle. When they came onto the screen, it looked like there were hundreds of people. But when I paid closer attention, I noticed that the mourners were the same villagers, circling in and out of the frame, and just changing clothes each time.” He laughs. “There were probably around fifteen people there instead of one hundred.” Sometimes, he adds, you can see the corpse sweat or the deceased’s chest rising and falling in the coffin. Most often, and more conveniently, the body will be cremated.

So will a company ever conduct DNA analysis on the deceased’s remains?

“You can’t do DNA testing with cremation,” Rambam says. Caitlin Doughty, the author of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory , has worked in Los Angeles crematories and funeral homes for nearly a decade. She explains why not: “DNA is organic material, and all organic material gets destroyed. Once a femur bone has been cremated, you can see right through it and crush it in your hand.”

Rambam and I discuss the DNA question over dinner on an unseasonably cool summer evening, sitting at a sidewalk table in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan. He flirts with the Ukrainian waitress, correcting her pronunciation of menu items. He gets distracted momentarily by the disproportionately sized head of a young man at the next table and refers to him as a pumpkin head. A middle-aged woman at the table next to ours gets her chair stuck in a crevice in the sidewalk and shouts, “I might fall in!” Rambam snickers. “Here’s hoping,” he mutters under his breath.

Pumpkin heads and clumsy co-diners notwithstanding, Steve gets back to business. While burning a body in state-of-the-art machinery might destroy all organic material, the investigations he has conducted abroad reveal different standards. “In third-world countries, their idea of cremation is not our idea of cremation,” he says, describing a coarser powder.

“Say no more.” I push my burger to the other side of the table.

Before digging up the coffin to see who’s inside, Rambam and Marquez always begin by following the paper trail. “Sometimes just checking the documents on their face,” Rambam says, “they’re going to be false. Sometimes you have to check the supporting documents. Think about what’s involved in a death: you have the body, you have the recovery of the body, you have the examination of the body, and you have the disposition of the body—whether it was buried or cremated. You can look into all these things.”

When he breaks death down this way, it’s kind of stunning. I had never considered this perspective on dying, authentically or fraudulently. When I think about dying, or what it would take for me to fake my death, I see the faces of the friends and family I would abandon. As Frank described, I would relinquish enjoying the small delights that make me me, and make me traceable. In my case, indulging in $7 manicures; visiting museums on Friday afternoons after the school groups have departed; twirling on the dance floors of dive bars. These are the things you must surrender when you disappear. This is the way most of us approach death: from the perspective of life—of love and work, of connection—the little moments that make the slog to the end worth it. Rambam’s concept of death, though, transforms it into boxes to tick off. He itemizes, indexes, and catalogs with bureaucratic efficiency. But that is what happens when your job is to try to divine the dead from the living. The juicy pulp of life gets replaced with documents, stamps, and official signatures. His workplace, in a way, is the DMV of death.

Not all people whom Rambam has investigated can cut ties and operate in the austere ecosystem of a second life. Some commit pseudocide precisely to pursue relationships begun in the first. In other words, they have mistresses. Rambam tells me about one of his favorite cases. He went undercover to stalk a Canadian with too many women. I thought back to what Frank told me about the different reasons that people fake their deaths: money, of course, either coming into it, owing it, or trying to get rich with an insurance scheme; violence; and then love, the bronze medalist of motivations.

“He had a wife and a girlfriend,” Rambam remembers, “and he dumped them both. I interviewed them, and it was incredible. They were like clones of each other. Anyway,” he says with a shrug, “I told them each about the other, and they spilled. They gave me everything. They said he’d told them both that if he could run away and hide, he’d go to Aruba and be a scuba instructor. So I went to Aruba and checked out the different scuba agencies. He was under a different name on a French passport: his name was Jack, and his passport said Jacques.”

Rambam saw an opportunity to mingle business with pleasure. “I was already a rescue diver, and to get my master certification, I needed ten more dives. I kept telling the insurance company, ‘I’m not sure it’s him, I need to take more dives!’ I was talking to a claims examiner, and she said, ‘As long as you’re not billing us for your dives, you’ve got a deal.’ I went scuba diving with him every frickin’ day. I stayed at the Marriott and got Marriott points. It was awesome.”

After racking up dives and watching the Canadian lothario from afar, Steve eventually made contact. “I asked him where he was from, and he said, ‘Canada, but I lived in California for a while.’ He told me a lot about his real life. Then I went out with him for a drink. When he went to the restroom, I took his glass in case we needed to do fingerprints. I took pictures with him. The girlfriend was the beneficiary on his policy, but she didn’t know where he was. The wife thought he was dead at this point. So I sent her our picture together, and she ID’d him. Then I went to him and said, ‘Look, I gave you my real name, but what you don’t know is that I’m an investigator. I’ve been investigating your death, and here’s the identification from your wife.’ He said, ‘So what happens now? Do I get arrested?’ I asked him to give me a video statement. I told him if he gave me the statement, I’d leave him alone, which was a lie. He gave his name and Social Security number and held up a copy of that day’s paper, just like in the movies, and he said, ‘I have no idea why people think I’m dead.’ ”

“So what happened to him?” I ask.

“I think the company didn’t bother with him,” he says with a shrug. Translation: the company rejected his insurance claim but didn’t file any criminal charges.

If you fake your death abroad and then attempt to claim life insurance, the crime you are committing is under the jurisdiction of the insurance company’s country. So if you attempt death fraud in Japan and then collect on an American life insurance policy, you are subject to American penalties. And since each state’s Department of Insurance is responsible for monitoring fraud, charges are rarely levied against death fraudsters. Nor do the local governments where these crimes are committed seem compelled to make examples out of no-goodniks. Marquez explains why:

“A lot of times, law enforcement will not readily act on these cases. Say you detect a fraudulent case here in the U.S. of a person who has traveled to China. It’s very difficult to get American law enforcement to prosecute a case. Even if we provide them with a lot of good evidence, they still have to conduct their own private investigation. Law enforcement would have to have the resources to send people to China to interview those involved, then bring them back to the U.S. to testify. It’s a very expensive and time-consuming process. The insurance companies are mandated to report fraud to the states; then it’s entirely up to the states to investigate and prosecute. A lot of states have budgetary problems, and pursuing life insurance investigations is complicated and expensive. Once we investigate the fraud and no money is paid out, there hasn’t been a financial loss to the company. Law enforcement usually doesn’t have the grounds to pursue ‘attempted’ fraud.”

Rambam counters his colleague’s claim, saying pointedly, “I try to get all my cases prosecuted. I’ll push the state’s Department of Insurance.” Quiggle maintains that insurance carriers are reluctant to bring death fraud cases to the forefront, but for a different reason: “Some companies are happy as clams to quietly pursue the case and let it be adjudicated through denial of the claim rather than bringing it into the public [sphere] and giving others tips on how to commit the same crime.” Ahem, others like me. With prosecution unlikely and a whole lot of earning potential, even Rambam realizes the appeal. “Life insurance fraud is very attractive,” he concedes. “A bank robber, on average, only gets about five thousand bucks, the money is traced with GPS, then he gets a gun stuck in his face, and he’ll get time in jail. In an insurance fraud, you probably won’t get caught, no one will stick a gun in your face, and you can collect from a hundred thousand to a million dollars. The problem is, people get greedy. But if the policy is under a certain threshold, it probably won’t be investigated.”

What cases like Mendoza and the Canadian scuba diver show is that if you are brazen enough to attempt life insurance fraud, the likeliest scenario does not involve spending time in the slammer. You just risk the humiliation of having your claim denied and being busted on your extended vacation.

So why doesn’t death fraud for insurance purposes take place as much on American soil?

The greatest obstacle is staging the accident. To be viable, you typically need a scenario where no body can be recovered. And drowning, which is most people’s go-to method, almost never passes the sniff test. “Ninety-nine percent of faked deaths are water accidents,” Rambam says. “In most drownings, the body is recovered. So why was this body not recovered? You happen to fall in on the only spot on the shoreline where there’s a riptide? And you didn’t wash up anywhere?” This demystification really blew my mind. I’d seen Sleeping with the Enemy , and besides the montage of Julia Roberts trying on adorable hats in the mirror, my big takeaway was that (spoiler alert) one must stage a drowning. No body, no problem! But Rambam sorted me out: this amateur understanding of death fraud is one of the biggest misconceptions and a common way that would-be death fraudsters get themselves caught.

Even attempting a more complicated accident can prove troublesome. Marcus Schrenker, a thirty-eight-year-old money manager from a flush Indianapolis suburb nicknamed “Cocktail Cove,” bilked clients out of $1.5 million by investing their money in a foreign currency that never existed, and was eventually reported to the state securities board. When, in January 2009, he realized the jig was up, Schrenker flew his single-engine propeller plane south toward the Gulf of Mexico. Nearing the Florida panhandle, he radioed air traffic control and reported turbulence, saying his windshield was cracking. He was hoping the plane would crash into the Gulf but it ran out of fuel about a hundred miles away. He put the plane on autopilot, opened the hatch door, and, at two thousand feet, parachuted out, and landed in the serpentine branches of an Alabama swamp. He wriggled out of his harness, splashed into the water, and made his way to a storage unit in Harpersville, Alabama, where he had stashed a motorcycle with cash and supplies the day before. But authorities apprehended Schrenker two days later as he hid out in a tent in Quincy, Florida, after he’d emailed a friend and detailed his plan.

Other innovative death fraudsters have attempted elaborate bait-and-switch schemes with crude methods. Jean Crump, a mortuary worker in her sixties who was employed at the now-defunct Simpson and McGee Mortuary in Lynwood, California, collaborated with a few friends to defraud several insurance companies out of $1.2 million. They held a funeral for one Jim Davis, who never existed. The casket they buried was empty. When insurance fraud investigators started nosing around, she realized she’d have to act fast. Exhuming the coffin, Crump and her associates filled it with cow parts and a mannequin, and then had the casket cremated. Investigators quickly unraveled the clever ruse, and Crump was charged with mail and wire fraud for filing a false insurance claim.

Rambam has investigated very few cases on American soil. Those types of death frauds are typically like Schrenker’s, people who get caught mere hours later. Staging the fatal accident is where pseudocides go awry. What you need is a disaster, natural or otherwise. Turns out that one of the greatest tragedies in American history, with the greatest loss of life, also resulted in some of the most shameless scams.

I MET JOE CROCE, a sandy-haired retired New York City Police Department detective and father of three, at an Applebee’s in Rego Park, Queens. Joe is one of those storied people who missed the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center by mere minutes. He was slated for a nine o’clock meeting with a Secret Service agent in the North Tower. They were working a case together. But Croce didn’t like the guy so he blew it off. He remembers seeing smoke billowing over Manhattan as he commuted in from Queens on the train.

Around 2001, Croce was a part of the Special Frauds Squad, an elite group of senior detectives who handled white-collar crime. Sergeant Dan Heinz, a third-generation cop from Staten Island, headed the operation. But once the towers went down, it was all hands on deck. Special Frauds was assigned to run one of the city’s many ersatz morgues that popped up to sort through the carnage from the Towers. “I drew the short straw,” Heinz explained to me over the phone from Texas, where he retired. Special Frauds ran a morgue and a center to report lost loved ones. It was on the West Side Highway, near TriBeCa, and the squad soon became the Missing Persons Liaison Unit. They set up a trailer in a parking lot adjacent to the World Trade Center site, where first responders dumped heaps of excavated corpses from the wreckage.

In charge of collecting as much identifying information as possible, Special Frauds detectives took exhaustive inventories from friends and family of features that might help distinguish a loved one trapped under the rubble. Croce explained, “Usually a missing persons report is a page or two long. These were like books. We asked, ‘What was your relationship with him? Does he have tattoos? Does he have rings? Does he have an inscription inside the ring? Does he have a hairbrush or a comb or a razor that we could get DNA from?’ Everything and anything. These reports were so thorough. We took all this information, and the computer crime squad entered the data.”

Collecting this data—from birthdays to birthmarks—was the easy part. “Our second job was to work at the morgue and to identify these persons. So if they came across a ring with an inscription, they could go into the database to see if there’s a match,” Croce explained. “We were weighing body parts and ID’ing each part in a system. So parts one hundred ten and one hundred twelve might be the same guy—”

“So you were, like, sorting through arms and legs?” I asked.

He smiled in a moment of hard-earned gallows humor.

“Everyone thinks a body part is a hand or a leg. But a body part can be a piece of your back, or just a hunk of flesh,” he said. Often, less than a pound of human flesh would be all that remained of a person. When family members came to collect their loved ones, Croce improvised a method to obscure this harrowing truth. “Sometimes you’d just have a little piece, and you’d have to throw it in a body bag. It looked like there was nothing there,” Croce said. “I remember blowing up plastic bags to fill up a body bag to give the impression that there was something in there.”

This was the bleak backdrop against which Sergeant Dan Heinz received a phone call from police in Oklahoma. It was a tip. Cops who had worked on the 1995 bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City advised him to be on the lookout for bogus death reports. “We noticed the first suspicious claim three or four days after 9/11,” Heinz told me. “Then a week or two after, we realized there would be more. We could have ignored it at first. But after a while, it became impossible.”

Missing persons reports in the immediate wake of the attacks climbed to over 6,000. But the official lives lost totaled 2,801 at the first-year commemoration. Of those more than 3,000 misidentified deaths, 44 were claims for either people who were still alive or people who did not exist. But no one knows how many weren’t caught. More, of course, could have evaded law enforcement. Imagine coming up from the subway, recognizing the tragedy, immediately computing it as an opportunity, an opening, and slinking away? Nothing filed, no attempt at life insurance—just a split second’s decision to vanish.

Most of the people Special Frauds ended up investigating didn’t fake their own deaths. Rather, they invented a fictional relative, saying that he or she had been killed in the attacks, and then tried to fleece money from charities and insurance companies. It was easy to spot the hucksters. Heinz remembers how blatantly transparent these charlatans could be. “You know something is up,” he said, “when people are very descriptive about certain things, like tattoos and appearance, but they can’t give fundamental information, like date of birth. People who commit fraud aren’t prepared for the simplest questions.”

Cyril Kendall was one of those people who had trouble producing the requisite documents. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, Kendall reported his youngest son (he had fathered twelve children), twenty-nine-year-old Wilfred, killed during a job interview at the financial services firm Cantor Fitzgerald on the one-hundredth floor of the North Tower the morning of 9/11. Kendall collected close to $120,000 from the Red Cross alone and another $40,000 from other charities before Special Frauds grew suspicious.

Croce asked the virile gentleman to supply a photo of his son. “So he shows up,” the detective remembered, “and he presents us with a photograph of himself, but much younger than what his son would have been. It’s a black-and-white photo, and he’s wearing clothes from the sixties.” The cops realized that Cyril Kendall was trying to pass off a photo of his teenage self as his missing son. “We were like ‘That’s you!’ ” Croce said with a laugh. Kendall served a few years and was then deported back to his native Guyana, but he never repaid the thousands of dollars he’d stolen, saying that he’d spent it all.

A handful of ingenious fraudsters latched onto the ruse involving Cantor Fitzgerald for their stories. A massive lightbulb went off over all their heads when the news reported that, due to the company’s unfortunate position at the point of the first plane’s impact, 658 of Cantor Fitzgerald’s 960 employees had perished.

Jilsey McNish, the invented wife of a man named Carlton McNish, was reported as a Cantor Fitzgerald employee who perished in the attacks. Her name was read from a list of the dead in memorial services in 2002 and 2003. Mr. McNish even held a fake funeral for his beloved. He collected over $100,000 from charities before it was discovered he never married. He served almost five years in prison for grand larceny after his fraud was discovered.

A mother-daughter duo from Milwaukee, Dorothy Johnson and Twila McKee, colluded to collect life insurance from two companies when mother Dorothy purportedly disappeared on 9/11. McKee was the beneficiary of both policies, totaling roughly $135,000. But Johnson’s fingerprints were identified on one of the claims forms stating she was dead. She also submitted an automobile claim to another insurer less than two weeks after she supposedly died. They were both charged with insurance fraud in 2003 and served three years in prison.

While all the other 9/11 fraudsters invented people (or used their own quite-alive family members) to report dead or missing, Steven Leung is the only person known to have registered himself dead in the attacks. He constructed the story that he had been an independent trader at Cantor Fitzgerald and had gone missing since the attacks. Or so said Leung himself when he posed as two different nonexistent brothers, Jeffery and William Leung, in attempting to arrange for his own death certificate. The real Leung had been living in the United States on an expired Chinese passport for years and had been arrested in Hawaii for using a fake Social Security number. He was out on bail when the 9/11 attacks took place. By killing off his former trouble-laden self, he would be able to simply adopt a new identity, avoid jail time, and begin a new life as a fully enfranchised citizen rather than live the shadowy existence of an undocumented immigrant with an outstanding warrant. So instead of attempting to squeeze some money out of charities, Leung used the disaster to become a freer version of himself, even seeking citizenship. (Exactly how he was to obtain citizenship after he was dead was never adequately explained.)

After faking his death in the attacks, Leung lived on as a reincarnation, but only briefly. In February 2002, just five months after his “death,” the twenty-seven-year-old Hong Kong man went to retrieve his correspondence from his commercial mailbox and was arrested on the spot. Had Leung received his original sentence only for passport and Social Security fraud, he could have served up to ten years in federal prison before being deported. At his trial, Leung admitted that the whole story was an elaborate hoax, saying he just wanted to get his passport case dropped.

“You were hoping,” presiding federal judge Denny Chin said, “that if the prosecution and the court believed that you had been killed in the World Trade Center attack, that the criminal charges would be dismissed?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” he replied.

Leung was sentenced to four years, including additional penalties for jumping bail and obstruction of justice. As we know, there is no explicit law on the books called “pseudocide.” But enough people try to pull a Steven Leung and phone themselves in as missing for the New York City Police Department (NYPD) to have carved out the classification of “self-reported missing” within the Missing Persons Department.

The only thing more surprising than those numerous brazen frauds is the breezy manner with which the detectives on Operation Vulture Sweep—as the 9/11 frauds that Heinz and Croce investigated became known—reminisce about this emotionally devastating era. Every police officer lost colleagues on that day. But recalling this traumatic time of sorting through human flesh and fused bodies at the makeshift morgue while simultaneously dealing with clowns like Kendall, McNish, and Leung, the detectives are not bitter. Instead, they harbor a resigned acceptance of low-budget, lowdown schemes.

“People were looking to take advantage of mass chaos,” Heinz said. “How could they not? It didn’t surprise me.”

Croce echoed Heinz’s sentiment: “I don’t think these guys are any worse than any other guys I’ve arrested for white-collar crime. They just try to take advantage of the system. Think about human nature. Do you want to pay for this, or do you want it for free? I almost don’t blame people who don’t have a pot to piss in. The weaknesses in our government and charity systems almost light up for them.”

Their nonchalance was hard for me to grasp, but maybe after a decade and a half they had simply found whatever sliver of light they could let in. I still felt queasy as Croce told me these stories. And I had trouble sifting out the most egregious aspect. Was it the fact that these schemers aligned themselves with people who had lost loved ones, therefore trivializing the memory of those who actually died, as well as the grief of widowed spouses and children? Or was it that they took advantage of the deep compassion that stitched together the wounded country? Death fraud, writ large, requires some instinct to deceive, to walk away, to bilk. When you fake your death, you make fools of the family members who grieve your loss; and, if you commit insurance fraud, you exploit a system intended to provide financial security to the bereaved. Maybe the backdrop of 9/11 serves only to highlight the darkness already at the heart of pseudocide.

I’d like to think that maybe these fraudsters were truly desperate, and they weighed the risk-reward equation. Given the grand scale of destruction, maybe Leung thought his crime of becoming documented was peanuts compared with terrorism. Maybe, since he was killing himself, he saw it as a victimless crime. But I was beginning to wonder if we can really pick and choose whom we harm and whom we protect.

AT THIS POINT, I’D spoken with people who had investigated death fraud but not yet someone who was considering committing it himself. So when a friend told me about an unsettling conversation she remembered having years ago with a cagey older co-worker at a happy hour, I asked her to put me in touch.

Todd put me on Bluetooth when he called from the road on a Friday afternoon. He was on his way to a campground in Northern California. He had left work early to beat traffic and get a few hours to himself before his wife and his two daughters, ages ten and eight, arrived. A forty-nine-year-old software manager from Lafayette, California, an affluent suburb in the East Bay, Todd spoke in a soft, nasally voice that skewed more surfer bro. He called me from the car with the windows rolled down because he couldn’t talk to me at home or at the office. He couldn’t talk in front of anyone else because we were talking about how he thinks of faking his own death.

“The only way to do it is at sea or to get blown up,” he told me. “You do it on a boat and find someone to witness it. First, I’d take out an insurance policy so I’d be gone but would know my kids could get a college education. I would arrange a sailing trip somewhere in Southeast Asia and make it seem like there had been a drowning. I’d head to Thailand because you can live in Thailand for nothing. I’ve traveled there, and I know how easy it would be. You don’t need anything, not even papers. I wouldn’t want to take any money with me, but I’d have some on the side, a few thousand. Now I’d have to make money, and I would do it online. I know I could make enough money to support myself under the radar—untraceable internet ad sales or something. It’d only make about ten thousand dollars, but I could live off that, just me, in Thailand, easy.”

Todd described himself as “a cog in the wheel.” In Silicon Valley, where baby millionaires are made overnight, Todd is uncomfortably in the middle. “The area isn’t great for my career, and technical jobs are hard to get,” he said plaintively. Depending on how hellacious the traffic, he spends fifteen to twenty hours a week commuting from the eucalyptus-lined suburb to his office in Marin County. As he sees it, “I will never be able to retire. Every penny goes into mortgage, family, bills. I have no plan for retirement because we will never be as comfortable as my wife wants.” Todd would be happy to spend his golden years living on a houseboat, but it’s not an option. “I mentioned that once to my wife, and she went ballistic,” he said. Todd has the life he thought he wanted: two healthy children, a wife, a house in the suburbs, and a good job. But he feels trapped. The idea of faking his own death provides fodder for his imagination during his commute and in front of his computer as he fantasizes about lazing on a Thai island, away from his responsibilities. Once, he Googled “faking your death” and was directed to the site wikiHow, on which someone had posted crude steps a person might take. Step one of the article instructs: “Decide whether you really want to do this.”

The thing that surprised me most about Todd was not that he wanted to fake his own death. (I’d done the same Google search). And his plan didn’t surprise me either. He sounded pleased with himself, like he had thought of everything—the drowning that would eliminate questions about a body, the insurance policy, the “untraceable” business model—but my research had taught me that his plan was really a pretty standard pseudocide. He’d likely get busted before he could even order a Singha beer.

But what did surprise me about Todd was his lack of sentimentality. I kept expecting him to qualify his plan somehow, to say something like, “Of course, I would never actually go through with it because I love my daughters too much.” Sure, he’d accounted for them, mentioning the insurance policy that was to pay their college tuition. During our conversation, as the wind muffled his voice over the phone, as he drove by himself on a highway three thousand miles away, I kept waiting for the hesitation. But I didn’t hear any.

STEVE RAMBAM HAS CAUGHT so many people that he knows what it takes to get dead and stay dead. But he requires a hefty burden of proof. “I don’t believe somebody is dead unless there’s an acceptable level of documentation, and by that I mean the New York City coroner took fingerprints, there’s a DNA match, and there’s a video of the person being run over by a car.” Todd’s brilliant idea of drowning and collecting life insurance without a body definitely would not cut Rambam’s mustard.

So how does a girl on the run—whether from debtor’s prison, from her psycho ex-boyfriend, or from the rote monotony of her life—evade the Rambams of the world?

Most of us cook up ideas like Todd’s.

And as I was learning, that skeletal plan is far from foolproof. While both Ahearn and Rambam discourage faking death as a means of disappearing, I couldn’t shake the feeling that simply vaporizing one day seems to lack the necessary narrative. If you don’t leave behind a body, why would anyone stop looking for you? Think of Etan Patz, the original milk carton kid who vanished in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood on his way to school in 1979. Based on new evidence, FBI agents excavated a building on Prince Street thirty-three years after the six-year-old went missing. Enthusiasts still hunt for D. B. Cooper and his money. Granted, I’m not an adorable kindergartner or a folk hero airplane hijacker, but I have enough connections (and outstanding debts) to think that I’d be chased were I simply to go off the grid one day. Corpses, or at least documents suggesting the existence of them, seem much more satisfying than a gaping, unsolved mystery. But I’m having trouble communicating this to Rambam, perhaps because he’s just seen so many cases that they all blend into one lackluster fraud, or maybe because me faking my death successfully is simply inconceivable to him.

One night, as Rambam is power walking up Broadway to interview a witness on a local case, I jog behind him with my recorder. I throw out a hypothetical:

“Say a bad ex-boyfriend is looking for me. Is it better to fake my death or to disappear?”

“The restraining order isn’t working,” Rambam assumes. “What other resources does the bad ex-boyfriend have? Is he gonna come looking for you if you move to another city?”

“Of course! He’s obsessed with me!”

Rambam looks unconvinced.

“If you don’t have someone looking for you, isn’t it better to fake death because it creates a story? Just disappearing seems too open-ended,” I say.

“You have to understand the ramifications of faking your death,” Rambam replies, becoming a little annoyed with my obstinacy. “First of all, you’re faking your death! You’re committing multiple crimes!”

“But what if I did it without collecting insurance or assuming another identity?” I ask, thinking back to Judge Procaccini’s specifications about how you could theoretically stay on the precipitously narrow right side of the law.

“So you leave your wallet in a car next to a waterfall . . .”

“Exactly! That’s not a crime.”

“You could argue that,” Rambam says wearily. “But it depends on what ultimately happens. Faking death might not be illegal, but the mechanics are. You’d have to lie to the police, and file a false police report and death certificate. You would have to bring people in on your disappearance unless there’s nobody in the world you care about. What about your mom, your dad, your pet? Would you give up your pet? Are you putting Fluffy in the gas chamber?”

Well, when he puts it like that . . .

“A lot of people who fake their death think that five or six years from now they’re going to reintegrate into things,” he says. This reminds me of the 1946 film noir classic Gilda , in which Ballin Mundson (played by George Macready) stages his death in a plane crash at sea to evade his pursuers. He returns to Buenos Aires, Argentina, three months later, only to encounter new problems. Many would-be death fakers opt for the Mundson route—like Sam Israel in his getaway RV—believing that staging their deaths can allow them to get out of a bind temporarily and then return home once their troubles have subsided. Rambam recognizes the shortsightedness of this plan: “Some people think they’re going to go away for a while and come back to be with their children. What are you gonna do, go see your kids and say, ‘Look, it’s Mommy’?”

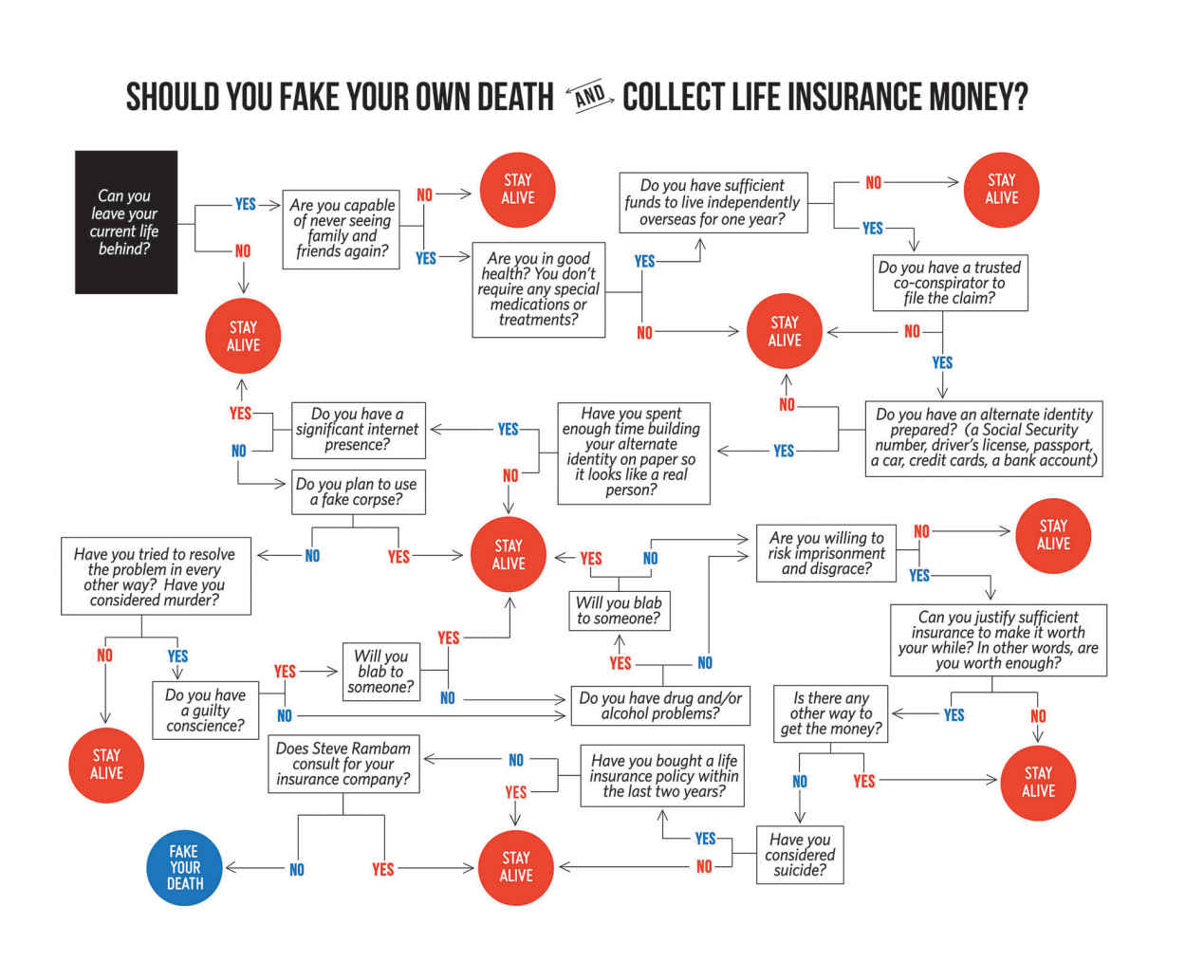

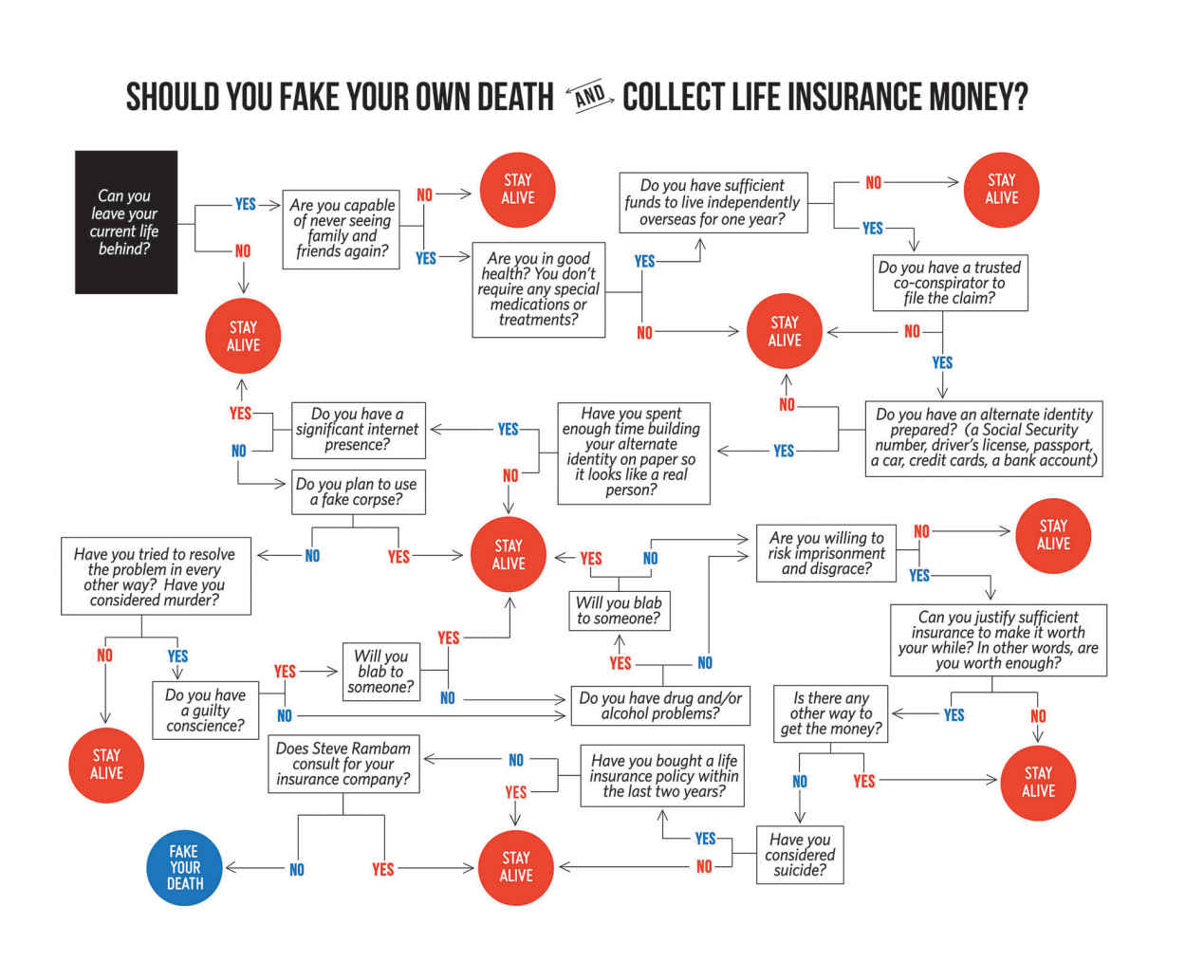

OVER DRINKS IN THE pressroom that day at the Marriott Marquis, I ask Rambam to walk me through each and every step that a potential life insurance fraudster should take into consideration. And I ask him to start at the beginning.

“Can you leave your life behind?” Rambam asks first. Amateur hour, I think. Just like Todd’s wikiHow article. Isn’t that the whole point?

“Are you capable of never seeing family and friends again?”

Okay, so that’s not for everyone.

“Are you in good health? Do you require any special medications?”

I’m healthy as a hambone.

“Do you have sufficient funds to live independently for at least one to two years while you wait for the insurance claim to come through?”

Here’s where it gets tricky.

“How much money are we talking here?” I ask.

“I say a minimum of fifty thousand dollars a year to live in Thailand. If not, what’s the point?”

I think back to Todd’s plan to live in Thailand on a few thousand a year. “What about a shack in Nicaragua?” I ask. My standards are subterranean.

“You might as well stay alive, then,” Rambam says, raising his substantial eyebrows at me yet again in a combination of charity and weariness.

“Okay, what about if your budget is more like ten thousand dollars per year? Or twenty thousand?”

“You just need more than that,” he says. “You’ve got to get a place, and you’ve got to get a place where nobody will spot you. Fifty thousand dollars. But that’s me. There are people who can live in a campground like a homeless person for two years.”

Jeez. I might be a pauper by New York standards, but living in abject poverty for two years might not work for me. Moving on!

“Do you have a trusted co-conspirator to file the claim?” Steve asks.

Now, who would do that for me, and how much would I be willing to give that person on the back end? Still, an accomplice to your crime isn’t always necessary, because, as Rambam explains, “If you gather all the information and documents you need, then the co-conspirator is gravy.” Besides, Mendoza’s henchmen turned on him.

Next!

“Do you have an alternate identity prepared?”

I have several working identities at any given time to avoid certain nemeses and to ingratiate me to others. With a few bourbons and on the right night, I’ll introduce Daphne Huckabee of the Savannah Huckabees. But what Rambam is getting at is something much deeper than the alter egos I bust out when drinking. What he means is the raw matter and material to operate in the world. Identity, I learn, is more than a whimsical character you put on at a bar to see how far you can get and to impress your friends. Identity today constitutes papers, documents, and a unique digital footprint traceable and peculiar to you. So what exactly do you need?

“You don’t need a passport if you’re not leaving the U.S., but if you want to fake your death, you’d be stupid not to have one,” Rambam says. “First of all, if you want to do a good fraud, you want to make it international. You want to have the fake identity in one country. You want to have the insurance policy in a second country. You want to have the accident in a third country. You want the beneficiary in a fourth country.”

Why?

“Most people don’t operate real well multinationally. Most investigators won’t go. And not only that, let’s say they catch you. It’s way harder to get all the evidence and all the witnesses and all the bad people from all the foreign locations.”

He continues, going over the list:

“You need a driver’s license, a Social Security number, a car you already bought.” The car thing is a big deal. So many people I’d read about got busted because of their cars, like Bennie Wint and his broken light. In How to Disappear , Frank Ahearn cites people being unable to part from their cars as the number one giveaway that gets them caught. Perhaps if you want to fake your death and remain in obscurity, the best move is to relocate to a metropolitan city and enjoy the wonders of public transportation.

You can get a fake passport and a working Social Security number easily enough. “Frankly,” Rambam says, “you can go out and buy a Social Security number. If you’re in Los Angeles, you go to MacArthur Park. There used to be a guy who sold Social Security numbers by the food carts in Queens.” But the stickiest part of constructing an identity on paper is fabricating your financials in a believable way. Rambam first told me that you would need to spend at least a year using the new bank accounts and credit history in your false identity. But then, when we discussed it further, he said you would actually need closer to a decade of recorded transactions under your proxy to make it believable. That’s some serious foresight.

There was one person I had read about who knew a thing or two about disappearing and leaving not a mark in the world. In 2009 Evan Ratliff, a co-founder of The Atavist Magazine and author of the Wired article “Vanish,” set up an interactive game wherein he would disappear for one month, and eager participants would try to locate him for prize money. It was hard to imagine that he could stay obscured for very long. Ratliff is devastatingly handsome, even with the strange half-bald haircut disguise he donned while he was off the grid. He rented an apartment under the identity J. D. Gatz (in homage to The Great Gatsby ), used prepaid gift cards and burner phones, and psyched out his trackers with disinformation. He evaded his pursuers until the final week. Surely he would have some insight into how one lives under an assumed identity.

On a humid Indian summer afternoon, Ratliff and I sat by the East River under the Brooklyn Bridge while I perspired through one of the three professional polyester H&M shirts I owned, with a sweat mustache accumulating on my upper lip. I asked him, “If you really needed to get out of Dodge, what would you need to consider?”

“If I was going to jail for the rest of my life for a crime I hadn’t committed, I would fake my death. The thing is, you need so much time,” Ratliff said, just like Rambam. And this rang true across the pantheon of guys who had gotten caught. The Wints, the Schrenkers, the Mendozas—all seemed to have botched already hasty jobs. But perhaps with the right amount of planning and care, you could get away with it.

“Money is the number one thing,” he continued. “Transferring tens of thousands of dollars into a crooked bank account is hard, because it can easily be traced back to you. So do you get it out in cash? I would spend a lot of time thinking about money. You can get a fake passport, and a fake Social Security number if you stay in the U.S. You can stay offline. You don’t have to get a smartphone. But what are you going to survive on? Are you going to work as a migrant laborer? Money is where it starts to hang up for me.”

I felt the same way. I can come up with all the creative costuming and backstory, but establishing the cash flow necessary to sustain oneself is where things get hairy. Coming up with the funds and then finding a way to obscure them while waiting to commit another financial crime—insurance fraud—means going from MacGruber to Jason Bourne with a touch of Gordon Gekko overnight. And given that so many low-rent con men fake their deaths because they’ve gotten themselves into hot water financially, perhaps compounding the problem would not yield the most desirable results.

Fine. My dreams are dying. But what else?

“You can’t have any significant internet presence,” Rambam tells me that day at the Marriott. “If you’ve got a Facebook profile with eight hundred pictures, I can start matching that to anybody else who pops up.” I think back to my conversations with Ahearn about managing information on the internet once it’s already out there. Even if you delete photos from your social media profiles, there’s always a possibility they never truly get erased; people take screen shots, report to other sites, bandy them about as they will. Not that I’ve ever Googled myself (ahem), but if I had, I might admit that an image search still brings up unfortunate photos of me from years ago, from profiles long deleted (which, sadly, coincide with the dawn of MySpace and a more experimental phase in my personal style, which included two-tone hair and low-rise jeans). Isn’t extracting your digital life nearly impossible?

“If you start a year or two in advance, you can do it. Stop tweeting, posting photos, all that,” Rambam says. And like Frank said, you can clog the search engines through tagging yourself as just about anyone, to create disinformation.

“Do you need to build up a presence as your new identity? To, like, make yourself more believable?”

“No, just stay the hell off completely.”

“Even if you use Tor?” I ask, referring to the software program that claims to obscure your browsing information and IP address.

“Tor is bullshit. There are ways around it. Like I said, just stay the hell off completely!” Rambam sucks down another Corona. I’m wearing his patience thin. Next!

“Do you have fingerprints on file?” he asks. Strange, I hadn’t yet considered this line of inquiry. Who has fingerprints on file? Hardened criminals, of course, and I vaguely recall an ominous elementary school project where we dipped our hands in blue paint to impress our tiny digits on cardstock, lest we get kidnapped on our way home from the school bus.

Then it dawns on me.

Of course I have fingerprints on file, from back in my teaching days. In order to pass a background check, the state fingerprints you to ensure that you are not a pedophile. Fingerprints on file, of course, means that you can be tracked that much more easily. Your unique loops and whorls will give you away if you plan on employing a stand-in corpse. If you want to hold a stately wake with keeners, processions, and a viewing of the deceased, like the kind that Marquez investigated, the body’s fingerprints can readily be cross-referenced.

“Do you have an intelligent method to fake your death?” Rambam asks.

“What’s an intelligent method?” I ask. Drowning has been unilaterally eliminated. (Ratliff and I shared a little chuckle over the conventional wisdom around faking death. Laypeople always offer the same solution: “Fake a drowning!”) “A shark attack? A plane crash?” I posit.

“There you go; there you’ve got a lot of variables,” Rambam says.

What about hiking? I ask.

“People disappear hiking all the time, legitimately,” Rambam says. “In my opinion, that’s a great way to disappear. Especially if it’s a young or middle-aged female, because women are snatched off hiking trails all the time for real, and raped and killed and the body hidden. That’s semibelievable.” Yikes. As a young(ish) woman who has gone on a solo hike or two, this point gives me pause. One of the glorious aspects of pseudocide, to me, was the autonomy I could exert over my story. But to be believable in Rambam’s eyes, I’d still need to summon the lurking madman out from the shadows to brutalize me. I couldn’t just slink off intact. For me to be reborn, it would have to appear as if my life had been taken. The thought frightens and depresses me.

At this point, Rambam’s longtime friend comes in maneuvering four Coronas, two for each of us.

“Yes! Please give her another drink! Maybe she’ll stop asking me all these goddamn questions!” Rambam shouts. But I am insatiable, fueled by beer and free cocktail wieners.

“Do you have a guilty conscience?” Rambam asks. This strikes me as odd. Obviously, people who are willing to abandon their families, debts, and obligations are categorically not handwringers.

I ask him to elaborate.

“A couple times people have given themselves up, but it happens very rarely. They go to the insurance company and give back the money. They don’t get prosecuted.” How odd.

The next few questions Rambam implores me to consider seem pretty straightforward: Do you have problems with drugs and alcohol?

(Loose lips sink ships.)

Is there any other way to get the money without committing fraud?

(I mean, I could infiltrate Sallie Mae and wipe clean its computers, but cyberterrorism seems a bit out of my wheelhouse.)

Have you increased your coverage in the past two years?

(Insurance companies consider a death within that time frame as a “contestable period” and will automatically scrutinize the claim.)

Are you willing to risk disgrace and imprisonment if you’re caught?

(I think part of the problem with someone who would consider pseudocide in the first place—me included—might be delusions of grandeur. How could I ever get caught?)

Then: “Can you justify insurance to make it worthwhile?”

Come again?

“A guy working at a hot dog stand isn’t going to get six million dollars in coverage,” Rambam explains. Mendoza’s net worth, for example, was approximately $200,000, yet he had policies in the millions, which immediately looked suspicious. “You have to make a lot of money, or you form a bogus company with your co-conspirators, and you both get key-man insurance.” He’s referring to certain business policies with greater coverage for important higher-ups in the organization. “There are a million ways to justify key-man insurance, but one of the reasons why I caught this guy in Mexico was because he was working for his brother-in-law’s garage, and he took out a million dollars from six different companies.”

Okay, so I’m worth about forty bucks and a scratch ticket. Gotta up my value. Rambam’s next question catches me by surprise: “Have you considered suicide?”

Back when we first started going over the viable motives for faking death, Rambam said that you had to have a legitimate reason, and he has yet to come across one. Which means that your problems have to be big: bigger than financial misdealings, bigger than love affairs, bigger than the average mortal mishegoss. What Rambam is getting at, I think, is that if killing yourself might also solve your problem, it might be a better option than faking your death. I thought about Hector and Todd and whether this option ever crossed their minds.

“So that’s where it all ends?” I ask. “Kill yourself or stay alive?”

“You ask yourself all the tactical questions, all the moral questions, all the strategic questions. If the stars align, you kill yourself. There are other questions you ask if it’s an emotional reason. Have you tried to resolve the problem? Have you considered murder?”

Whoa! Not sure how we went from pretending to take your own life to actually taking the life of another, but this is where the road leads: to annihilation, to blotting out. For Rambam, it seems that taking your own life is more honest, somehow nobler, than staging the exit. But if actually killing yourself or committing murder still won’t solve your dilemma, and faking your death remains the only option on your road to glory, then Rambam (thank you, ma’am) has one last question for you: “Does Steve Rambam consult for your insurance company? If yes, stay alive !”

In Rambam’s entire career of tracking down fraudsters on the lam, he says that only one person has ever evaded his capture: a Mongolian woman whose good friend was married to the local police captain and used his connections for her plot. She has been hiding out and avoiding extradition in France ever since. She sounds like a smart lady. “If she ever goes back to Mongolia, there will be a bunch of angry cops there waiting for her,” Rambam says. You can tell he harbors a teensy bit of ire at not being able to claim a totally flawless track record. But it’s pretty damn close.

After he’s laid down all the different questions, big and small, that a carefully considered pseudocide would need to address, I feel wrung out and crestfallen. Clearly, pulling off a hoax on your own mortality involves some serious planning.

“Don’t you think there’s anything romantic about faking your death? Daydreamy, even?” I ask him. He looks at me as if I am insane; as if I’d had wads of cotton lodged in my ears for our entire stiff conversation; as if I’ve just blatantly disregarded the lengths to which he goes to smoke out criminals from their garrets, and the shame leveled upon them when he does.

“It’s not colorful,” he says in a voice quieter than I’ve heard him use yet. For a moment, his bravado is gone. “It’s actually pretty cowardly.”

Ahearn, Rambam, and even Ratliff agreed that, logistically and in terms of its success rate, faking death is not the way to go. And now Rambam was refuting my poetic notions about fresh starts and clean slates in exchange for the image of an invertebrate con man slinking away. But I still wasn’t convinced. Is it cowardly to renounce problems that feel so deeply entrenched to the point of total despair, or is opting out entirely the ballsiest move one could make? It was time to hear from someone who knew firsthand.