THROUGHOUT THE WAR and afterwards, until they were demobilised, millions of men and women wore the distinguishing uniforms and insignia of the organisations with which they served, demonstrating their wartime role. The Second World War was the first conflict in which females were conscripted, so the adoption of uniform applied to many more women than ever before. The appearance of women in uniform throughout Britain, from nurses to mechanics, came to be one of the defining features of the war years. For all those issued with official kit, their uniform identified them and formed the basis of their wardrobe. Much has been written elsewhere about military uniforms, so here the focus is on some of the special uniforms adopted by women for wartime work and the ways in which the circumstances of war impacted on civilian dress.

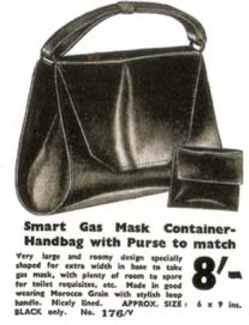

A potent symbol of the war was the gas mask, first issued in Britain in 1938, when the threat of chemical warfare seemed very real. Although carrying a gas mask never became a legal requirement, when war was declared in September 1939 the population was urged to take precautions and always to carry a gas mask when leaving the house. Commercially made gas-mask cases swiftly went on sale, styles ranging from oilskin covers to smart leather handbags with compartments for the respirator. The gas mask became an integral part of a woman’s outfit and even the Queen carried one to her public engagements. However, as the war dragged on and no gas attacks arrived, civilians became more lax and eventually gas masks were discontinued.

The chic navy-blue uniform of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, displayed in recruitment posters, inspired many more young women to apply to join the WRNS than there were places available.

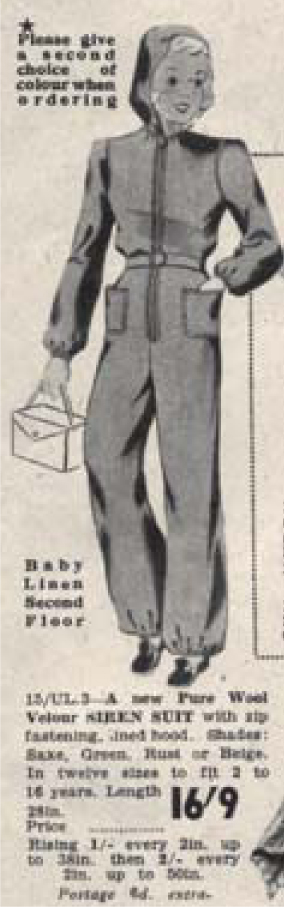

Another sartorial expression of the events of the war was the airraid emergency suit or ‘siren suit’, a roomy zipper-fronted one-piece jumpsuit that could be put on over anything when the air-raid sirens sounded – pyjamas or a nightdress, if necessary. The comfortable siren suit, popularised by the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was similar to the overalls or boiler suit used by mechanics, tank crews and others to protect their clothes, but often featured a snug hood. The suits were available from shops and mail-order catalogues in various colours and all sizes, for adults and children, while some were made at home from patterns, using woollen material or any warm fabrics available under the rationing system.

Siren suits were just one of many instances of females adopting trousers during the war – born of necessity, this key dress trend would influence future fashions. Casual trousers or ‘slacks’ were already worn by some women for outdoor activities such as gardening and sailing and were made fashionable by influential film stars such as Katharine Hepburn, but the masculine garments were not yet widely accepted as ‘decent’. Even when British women donned practical trousers, overalls, dungarees, jodhpurs or other styles of breeches for physically demanding wartime jobs, convention prevailed when it came to everyday dress: for example, in some rural areas trousers were regarded as the dress of the immoral woman and, perhaps for similar reasons, many traditional working-class men disliked seeing their wives and daughters wearing trousers.

An advertisement for a smart gas-mask handbag, c. 1940 – one of various styles marketed during the early war years.

This advertisement for siren suits from Barker’s of Kensington displays a range of colours and sizes.

Government recruitment posters depicting glowing, rosy-cheeked girls wearing country breeches and sweaters inspired many females to join the Women’s Land Army in preference to military conscription or factory work. Land Girls were typically young, aged in their late teens or early twenties, and came from all walks of life. They received an official uniform comprising a short-sleeved cream aertex shirt, a green V-necked ribbed woollen jersey, a green necktie, brown corduroy knee breeches, fawn-coloured knee-length socks, brown lace-up shoes, an armband (worn mainly on parade and for press photographs), a brown felt hat – or a green beret for those working in the Women’s Timber Corps – and a badge. Additional Land Army standard-issue workwear included a belted overcoat, short mackintosh, bib-and-brace overalls (dungarees), rubber boots, and sou’wester hats, although in practice a variety of practical clothes was worn. The provision of a range of dress articles for cold, wet and hot weather meant that Land Girls from poorer backgrounds enjoyed a decent wardrobe for the first time, with comfortable outfits suitable for all seasons. Women also became physically fit working on the land: the undernourished filled out and the overweight slimmed down; hygiene improved too, as modern sanitary towels were provided and teeth were cared for properly.

Barker’s of Kensington stocked everything for the practical female wartime wardrobe from ‘air-raid emergency suits’, through bib-and-brace overalls to tailored jacket and jodhpurs for land wear.

Many women wore masculine jackets and jodhpurs or breeches for outdoor jobs vacated by men, such as delivering milk, as seen in this snapshot dated 1941.

Special civilian uniforms were developed for numerous jobs taken over by women during the war. Women’s involvement in the transport system was especially prominent and female bus drivers and conductors (‘clippies’) were a familiar sight on many bus routes. Their hurriedly devised uniforms were an adaptation of those worn by men. Female railway guards, station staff and postal workers dressed similarly to bus staff. Women even entered the fire service for the first time, as watchers, drivers and despatch riders: their main uniform comprised a navy woollen suit with either skirt or trousers, a soft fabric peaked cap and a steel helmet. Other women, including ARP wardens, also wore helmets at work.

This wartime clippie, wearing her London Transport uniform and Public Service Vehicle (PSV) bus conductor’s badge, was photographed in 1944.

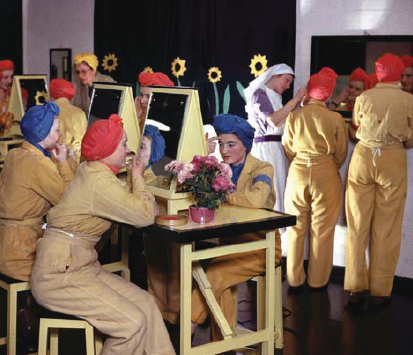

To many, it is the iconic image of the Second World War female factory worker wearing an industrial ‘uniform’ that best symbolises women’s contribution to the war effort. Often undertaking work that was extremely physically demanding, working long hours and having rapidly to learn complex skills that men had taken years to master, women laboured at the heart of British manufacturing, operating deafening and dangerous machinery and frequently handling hazardous materials. Factory workers enjoyed none of the glamour of women in the services with their smart, tailored uniforms and jaunty peaked caps, but understood the necessity of their role in keeping the cogs of heavy industry turning throughout the war. Garbed in tough protective clothing comprising shapeless utilitarian dungarees and overalls, they also had to wear unflattering hairnets or headscarves tied into turbans. First appearing in 1936 as an exotic high-fashion style, the turban was, however, a versatile item: used widely in factories to protect clean hair from polluted factory environments and as an essential safety measure when using dangerous equipment, turbans soon became a major wartime fashion.

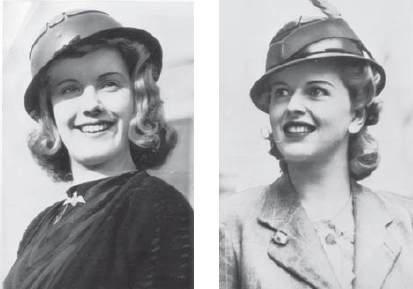

Propaganda photographs from 1940 portraying attractive models aimed to encourage women in dangerous wartime occupations to wear protective steel helmets.

This painting by Dame Laura Knight (1943) of factory worker Ruby Loftus wearing industrial overalls and a hairnet while turning a breech-ring is one of the most iconic images of the Second World War.

Cosmetics were also worn in the factories, partly to offset the unfeminine industrial workwear, although face creams were positively recommended to help protect the complexion from toxic chemicals. British munitions factory workers were awarded a special allowance for face creams in 1942 and occasionally a sales representative from Max Factor would turn up with free products, boosting workers’ morale. Factory staff worked long shifts and were usually employed precisely when the shops were open, but many firms, understanding the problem, arranged for their workers to have time off, perhaps a half-day or two ‘shopping break’ hours per week. Alternatively, key workers were sometimes allowed to register in advance for rationed goods, or older unemployed women might be appointed professional shoppers on behalf of the factory girls – a carefully devised arrangement that suited both parties.

Royal Ordnance Factory workers wearing their ‘uniform’ of overalls and turbans apply face cream at the make-up station, to protect their complexions from toxic substances.