Knitting wool was highly prized during the war and many garments were knitted at home, from jerseys and cardigans to outdoor hats, scarves and gloves for the whole family.

STRICT CONTROLS OVER civilian use of resources needed for the war effort led to the scarcity, even disappearance, of various dress-related articles and cosmetic products. Improvisation and effort were required to contrive an attractive, respectable appearance and, importantly, to raise morale when times were hard.

Supplies of leather, rubber and silk – raw materials commonly used in the manufacture of dress items – were all adversely affected during the war; consequently a number of synthetic textiles developed during the previous decades came into wider use, such as rayon, favoured for Utility clothing. Leather shortages were less acute in Britain than elsewhere and shoes were manufactured to high standards. Utility-grade footwear was fashioned from sturdy leather and often had leather lining and double soles, creating rather heavy-looking shoes that would last for years without frequent repairs. However, to lessen the demand for leather, when rationing was first introduced, wooden-soled clogs were offered coupon-free, but remained unpopular, being long-associated with poverty and the mills and factories of northern England. Following the fall of Malaya (Britain’s main source of rubber) to Japan in early 1942, rubber soles and heels for footwear were prohibited, except for the services and key occupational uses. More fashionable wooden-soled shoes were introduced in 1943, rigid-soled footwear that required a certain way of walking. Synthetic rubber soles appeared in 1944, while crêpe rubber was often used for the soles of bulkier shoes. Despite the shortages, the Board of Trade did allocate some rubber and steel for the continuation of corset production. During the 1940s many women still favoured a firm foundation garment – a girdle or corset that slimmed, supported and smoothed the contours of the body and that had garters attached for fastening to the tops of stockings.

Sturdy leather shoes often had synthetic soles, owing to rubber shortages. This Saxone advertisement appeared in Ideal Home magazine in December 1945.

Silk for stockings was prohibited in January 1941, the main substitutes being rayon and cotton. Sometimes ‘nylons’ – strong, sheer, lightweight nylon stockings developed in the United States in 1939 – could be found on market stalls and were occasionally available in shops; however, these were usually expensive and when they laddered had to be invisibly mended. There was also a flourishing black market for stockings, but good hosiery was scarce until the United States entered the war at the end of 1941: American GIs seemed to have an endless source of silk or nylon stockings. Going out in public without stockings was not considered respectable and, as their supply dwindled, many women in Britain resorted to faking the effect of tan-coloured stockings. Some managed to obtain quality cosmetic lotions for painting on the skin, but reputable products were costly and became increasingly scarce: more common were cheaper brands that were notoriously unreliable, some turning the skin bright yellow or permanently staining clothes. Consequently many older girls and women tried home-made alternatives, the most popular being liquid gravy browning and cold tea or cocoa, applied with a sponge or cotton wool, with a line sometimes drawn up the back of the legs with eyebrow pencil, to emulate stocking seams. However, gravy browning and other rudimentary substitutes often streaked and were not waterproof. The lack of decent stockings was a major frustration for women: even when the war ended, British factories engaged in spinning nylon for parachutes took a long time to switch back to producing yarn needed for stocking manufacture.

Silk for stockings was prohibited in January 1941. Du Pont was a major American manufacturer of the sheer nylon stockings that were sometimes available in Britain during the war.

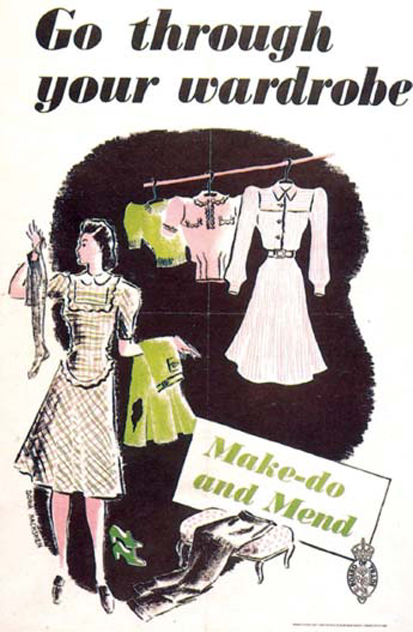

This wartime poster urged the public to ‘Go through your wardrobe’, to ensure that every existing item of dress was fully utilised in times of growing shortages.

Throughout the war and its aftermath, the government was anxious to reduce consumer demand for new clothes whose production would drain valuable human and material resources. In the summer of 1942 the Board of Trade launched a ‘Make-Do and Mend’ campaign to encourage civilians to ‘utilise every old garment before considering anything new’. Of course, the concept of making do and mending was not new to poorer and ordinary working families already accustomed to extending the life of their clothes until they were no longer wearable; however, the upper-middle and upper classes were now having to manage without their ladies’ maids, perhaps for the first time. When upmarket magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue and Tatler supported the government’s initiative by exhorting their readers to ‘learn how to look after your clothes … find out the right way to mend and iron’, they were chiefly addressing privileged ladies who were unfamiliar with such basic domestic tasks.

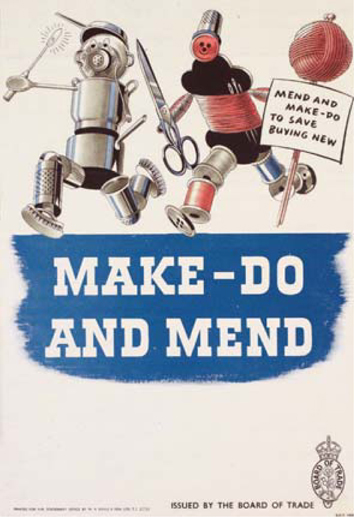

The ‘Make-Do and Mend’ scheme was personified by a doll-like character called Mrs Sew-and-Sew, who was pictured on various posters darning, patching and washing clothes.

The Make-Do and Mend campaign appealed to the British public’s keen sense of patriotism. As Hugh Dalton, the President of the Board of Trade, pointed out: ‘When you are tired of your old clothes, remember that by making them do you are contributing some part of an aeroplane, a gun or a tank.’ Numerous ‘how-to’ booklets were published, concerned not with fashion, but with the care and survival of clothing. Although millions of women already made some of their own and their children’s clothes, magazines such as Housewife produced guides to making and mending various garments. Similarly, the ‘Sew and Save’ features in the Daily Mail detailed every step of home dressmaking, including planning a smart but functional wartime wardrobe, while the Daily Express booklet ‘War Time Needlework’ also included help with knitting. There was no shortage of practical information available concerning sewing, darning, patching, knitting, washing, ironing and recycling articles of clothing.

Both the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) and the Women’s Institute (WI) ran Make-Do and Mend evening classes, while some women inexperienced at sewing taught themselves the basics of home dressmaking. But even with the necessary skills, the process of creating garments was not easy, given the fundamental fabric shortages. In the true spirit of improvisation, coats were sometimes fashioned from blankets and dresses from twill blackout material or old curtains. Parachute silk was not easy to obtain, legally or illegally: until it was officially made available for sale in 1945, to acquire it for civilian use was a crime. Those who obtained parachute silk stolen from parachute factories or via the black market generally used it to make underwear or wedding dresses, although this was not common practice. However, resourceful dressmakers would use any scraps of material to create wearable, if sometimes unusual garments: for example, some made patterned blouses and dressing-gowns from geographical maps printed on silk. Patriotic printed materials were also popular with home dressmakers, such as the red, white and blue ‘Victory’ print. When items of dress became tired-looking, they could be re-dyed, although reliable commercial dyes such as Drummer or Tintex were scarce and most other dyes tended to be fugitive: garments did not take the colour evenly, while domestic substitutes such as ink usually led to disastrous results. Shoes, too, were sometimes dyed or painted black, but would turn stockings and feet blue in the rain. In spite of such trials, many women worked hard at keeping up appearances: looking a little shabby was acceptable, but to let oneself become slatternly – a drop in personal standards soon spotted by friends and neighbours – was a visible sign that circumstances were taking their toll.

The Board of Trade’s ‘Make-Do and Mend’ initiative aimed to encourage good clothing-care practices to extend the life of existing garments before new purchases were considered.

A good winter coat was considered essential and skilled dressmakers might make their coats using paper patterns, like this McCall pattern from 1940. During the war some women cut down and altered their absent husband’s overcoat.

One of the most useful materials of the 1940s was knitting wool. Many women knitted ‘comforts’ for the troops – socks, mittens, mufflers and balaclavas – and also made sweaters, hats and scarves for their families, from any colour and quality of wool available. No spare wool was ever discarded and adult garments were often unravelled and knitted into new clothes for children. Many women, who spent their evenings at home sewing, darning and knitting while listening to the radio, knew that such tasks were essential but found them laborious. It was easy for busy mothers to become exhausted and demoralised from running the house single-handedly, caring for children, completing never-ending chores and from broken sleep due to the wailing sirens and nights spent shivering in air-raid shelters, but neighbours, family and friends rallied round and helped to keep up one another’s spirits. Many women experienced a heartening sense of comradeship during the war and readily pooled their clothes, sharing, swapping and borrowing items, particularly for special occasions, such as a wedding. Sometimes certain articles, for example hairnets or knicker elastic, would suddenly become unavailable for months at a time, but scarce goods could often be purchased on the black market. Second-hand shops and pawnbrokers also flourished as women who once would not have dreamed of wearing cast-offs clothed themselves and their families by whatever means necessary.

Patriotic materials and knitwear were popular throughout the war. This ‘Victory jumper’ knitting pattern appeared in Home Notes magazine on 2 June 1945.

Traditionally, smart accessories such as these matching leather and crocodile-skin handbag and shoes, completed an outfit, although during the war compromises had to be made.

Smart accessories traditionally completed the overall effect of a good outfit. Hats were not included in the rationing system and many women felt that attractive, eye-catching millinery was one of the few ways left in which they could express their personal style. A variety of headwear was fashionable during the 1940s, from tall, feathered bonnets, through military-style caps, to mannish hats tilted forward on the head. However, as the war advanced, materials including straw and felt became increasingly scarce; hats were subject to a heavy 33 per cent tax as luxury items and prices rose dramatically. Many ordinary women were eventually forced to make their own headwear and consequently turbans, pixie hoods and stylish snoods – netted bags containing the hair – all became popular. Magazines and pattern companies provided instructions for knitted or crocheted tam-o’-shanters and berets, while the headscarf became fashionable with the younger generation, including the royal princesses. Turbans and scarves could conceal curlers – often worn at work before an evening out – or unwashed hair, but women who preferred a more formal image followed advice published in books and magazines for cleaning straw, refurbishing lace and reconditioning the sable or fox fur of their existing hats, to present a well-groomed, dressy appearance.

Headwear was not rationed and many women found that a stylish hat enabled them to express their individuality. This fashionable hat is teamed with a smart Utility Marlbeck suit from Leeds clothiers Thomas Marshall Ltd.

This illustration in a Marshall & Snelgrove catalogue from 1944 demonstrates the wartime fashion for scarves and turbans, which were inexpensive and could, if necessary, conceal unwashed hair, even curlers, before a night out.

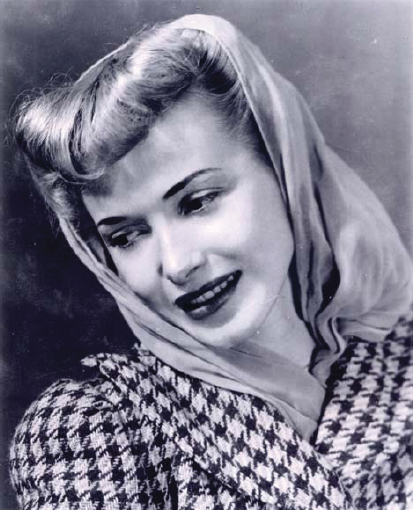

This professional dancer, photographed c. 1940, displays the kind of film-star glamour that was idolised and emulated by ordinary women.

While many women went to great lengths to display stylish headwear, younger females especially were only too pleased to go without hats and to draw attention to their hair, in the manner of contemporary film stars. Actresses in vogue during the 1940s included Ann Todd, Celia Johnson and Margaret Lockwood, their immaculate make-up and hairstyles and stylish costumes reflecting a classic English femininity, while American stars such as Dorothy Lamour and Lana Turner promoted a bolder, more modern glamour. The most popular movie icon in the mid-war years was Rita Hayworth, whose gleaming auburn hair cascaded down her back, while Veronica Lake’s famous peekaboo hairstyle, falling sensuously over one eye, was seen as the ultimate in sexiness.

Even a simple headscarf could look glamorous when worn with stylish clothing, well-styled hair and cosmetics.

Long luxuriant hair, jewellery and cosmetics made a woman feel feminine and alluring, as demonstrated in this family photograph taken c. 1948.

Women in the services had to keep their hair off their collar but civilians often wore theirs longer and, as clothing grew increasingly scarce and uniform in appearance, glorious hair became ever more important, providing a sense of allure and a way of keeping pace with fashion. Hair was dressed in waves and curls, the front hair usually rolled and pinned back off the forehead, the length curled under or left looser, to softly frame the face. One fashionable style was the patriotic-sounding ‘victory roll’, named after a fighter plane manoeuvre. Despite the shortages of hairpins, hairnets, setting lotion and even shampoo at times, the carefully styled 1940s hairstyle helped civilian women to attain an aura of glamour amidst the uniform austerity of dress.

By the 1940s the cosmetics industry was well established and a regular beauty regime was a source of great pleasure and confidence to countless women: a clear complexion, bright lips and accentuated eyes, along with a feminine hairstyle and jewellery, could almost compensate for old, uninspiring clothes and down-at-heel shoes. Women’s magazines were full of seductive advertisements for skin-care, hair products and make-up, and wartime beauty tips. Cosmetics companies ingeniously represented their products in a patriotic light, as a form of ammunition necessary to fight the war: pursuing ideals of beauty was no frivolous preoccupation, but a clear act of defiance, almost a national duty. Yardley declared:

Never must careless grooming reflect a ‘don’t care’ attitude … we must never forget that good looks and good morale are the closest of good companions. Put your best face forward.

Women’s magazines were full of enticing advertisements for beauty products, like this one for Pomeroy from Ideal Home, December 1945.

Similarly, Elizabeth Arden’s wartime campaigns focused on elegant sketches of women in uniform, announcing ‘Beauty Marches On…’, while some products were given bold military names, such as Auxiliary Red – Cyclax’s rouge and matching ‘lipstick for service women’. Famous film stars were also used to endorse cosmetics – the glamour role models for millions of women.

By 1942 the supply of beauty products in Britain had fallen to less than 25 per cent of the level recorded for 1938, yet, despite desperate shortages, there was generally some way of acquiring cosmetic aids. There are many tales of makeshift measures: for example, the ends of used lipstick tubes were carefully collected, melted down and poured into a container to re-solidify, and, when lipstick ran out completely, solid rouge or beetroot juice was used on lips. Likewise, eyes might be outlined with soot or charcoal, or even boot polish, and the lids shined with Vaseline, while an infusion of rose petals provided a coloured liquid for cheeks. When cold creams and make-up removal products disappeared, many women used lard instead. Hands were difficult to care for when a woman was engaged in rough work and Land Girls working on dairy farms would borrow the salve used to soften cows’ udders to ease their chilblained hands and fingers. Beauty products and the many substitutes used during the years of austerity played an important role, helping women to maintain the impression of a normal appearance and, especially, enhancing their sense of femininity and self-esteem.

Glamorous Hollywood film stars were often used by cosmetics companies to endorse their products, as seen in this 1949 Max Factor advertisement featuring Elizabeth Taylor.