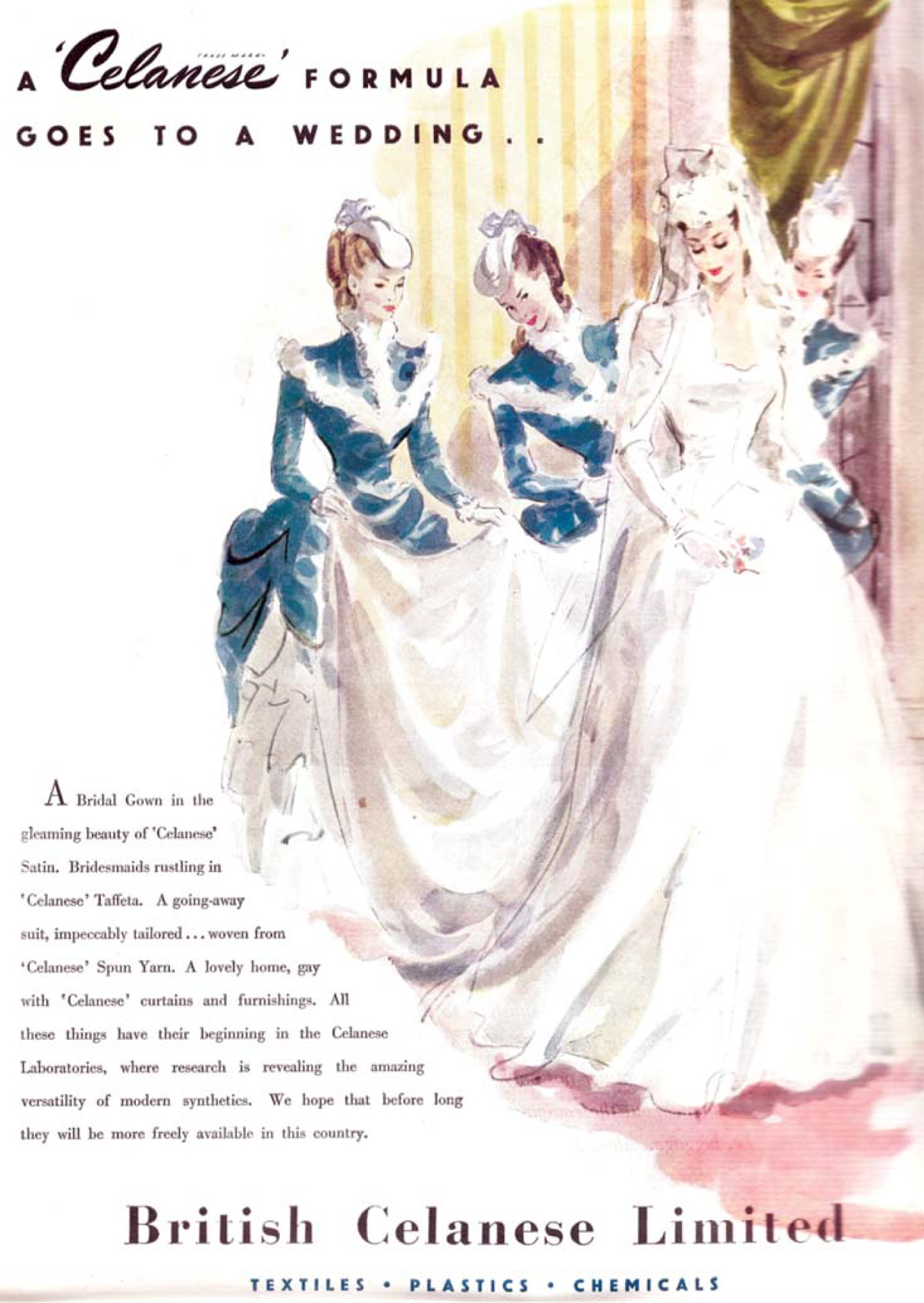

Fashionable late-1940s bridal wear often featured a New Look-inspired cinched waist, padded hips and full skirt, as displayed in this illustration from The Sphere, June 1949. Synthetic fabrics such as Celanese rayon were popular silk substitutes.

For most women the occasion when their appearance matters most is their wedding day, but 1940s marriage ceremonies and celebrations were dominated by the events of the war. Peacetime weddings could be planned well ahead, the bridal dress, flowers, going-away outfit and trousseau carefully selected, but wartime weddings were often spontaneous, even chaotic affairs, arranged hastily before the imminent departure of bride or groom, or organised at short notice following news of a brief 48-hour period of leave. Marriage assumed a heightened emotional significance during the war and represented the continuity of fundamental social values when all around seemed uncertain. It remained virtually every woman’s dream to have a traditional white wedding with a church ceremony, but this romantic ideal often had to be modified in the face of reality.

In 1940 the conventional ‘white wedding’ was still common but the introduction of purchase tax in October and clothes rationing in June 1941 soon affected bridal choices. Improvisation and ingenuity were required if bridal traditions were to continue. Elegant trained dresses from the late 1930s were often loaned by friends or relatives, while some brides resurrected their mothers’ ivory wedding gowns from earlier decades, altering them at home or, if finances permitted, using a professional dressmaker or the garment-alteration service of larger stores. If any material was left over, it could, for instance, be used to make a hat or headdress. Some 1940s brides wore a full-length vintage or antique lace veil – perhaps a family heirloom that fulfilled the custom to wear ‘something old’; otherwise a shorter, modern veil could be hired or purchased.

White 1940s bridal dresses typically featured a narrow skirt without a train, owing to material shortages. In this wedding photograph from October 1944 we also see the 1930s-style tiara headdress that was often worn during the war.

Wedding gowns were sometimes available to buy during the war, although rationing made this difficult and families often had to pool their precious coupons to purchase a special wedding dress. Ready-made bridal dresses were priced from around £4 upwards and could cost well over £20. Synthetic materials were cheaper than natural silk: for example, in 1944 Derry & Toms advertised a rayon satin bridal dress for £13 15s 6d and seven clothing coupons. There was often a waiting list of several months for new dresses, so wartime brides frequently resorted to making their bridal outfits at home. Curtain lace, exempt from the points system, was often used to fashion a veil and a long dress that could be worn over a white nightdress. Occasionally parachute silk was acquired for making into wedding dresses or bridal lingerie for the trousseau. Whatever the fabric used for the gown, there was generally little material to work with. Consequently the bodice had to be close-fitting and the skirt narrow, made without a traditional long train. Shallow V-shaped, square and heart-shaped sweetheart necklines were all popular and long tight-fitting sleeves using minimal fabric were puffed or padded at the shoulder. If material allowed, the bodice might be ruched, but generally new bridal gowns were relatively simple and slender, expressing the economical style. The veil, attached to a late-1930s tiara-style headdress or a tall frame, was generally worn far back on the head, revealing carefully styled hair. Additional touches, such as gloves crocheted from white cotton, helped to complete the bridal image, along with a modest bouquet and perhaps a good luck boot, heart or horseshoe suspended on ribbon.

Bridesmaids were dressed in whatever matching or complementary clothing could be acquired: their frocks were typically fashioned from plain pastel-coloured or floral-printed material and featured padded shoulders and puffed sleeves, adult bridesmaids usually wearing short shoulder-length veils.

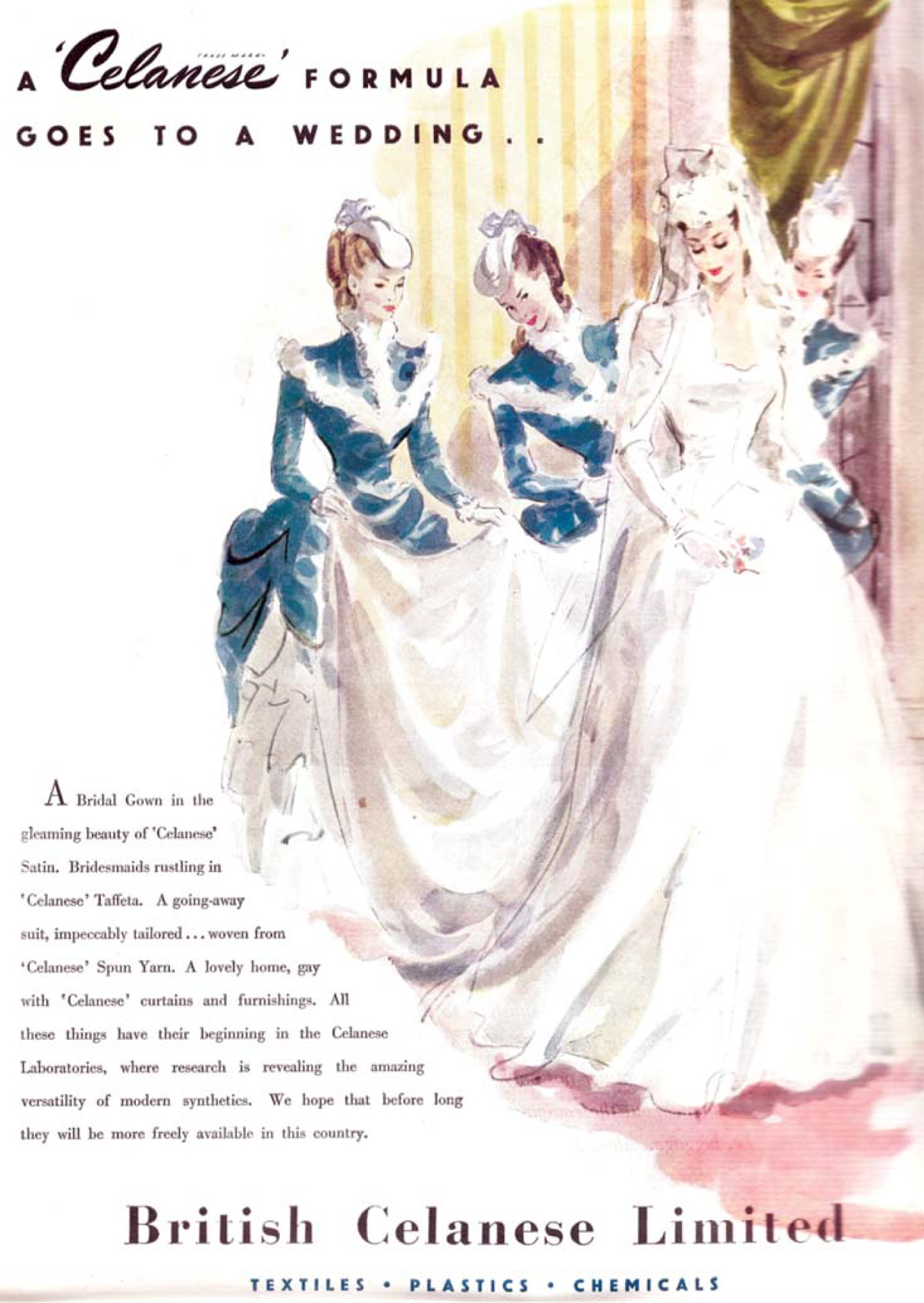

As shortages became more acute and the mood of austerity deepened, many considered it inappropriate to host an ostentatious event. Almost every essential for a conventional wedding was either rationed or prohibited, from rice or confetti to royal icing for the cake. Even wedding rings were not easy to obtain, owing to the lack of gold available for jewellery. Sometimes women joined a long waiting list for a 9-carat Utility wedding ring, whose high copper content turned the finger green; however, there were not enough to go round and often an inherited ring was worn, or a gold band borrowed for the ceremony. As early as June 1940 Harper’s Bazaar had published a wedding feature displaying attractive suits and dresses in lieu of white bridal wear, and as the war advanced it became increasingly common for civilian brides to marry in a fashionable daytime outfit. Doubtless some felt disappointed at being unable to have a dreamy white wedding, but others appreciated the sense of freedom and modernity as they walked confidently down the aisle in a smart Utility outfit and stylish accessories. A fitted knee-length dress or sharp tailored suit, with a jaunty hat perched atop a glamorous waved hairstyle and a floral corsage pinned to the lapel or a neat bouquet held in a gloved hand, typified the civilian bridal wartime look.

This ivory silk wartime bridal gown designed by Modèle Shandel of London probably dates from c. 1940, before silk was prohibited for civilian use in Britain.

1940s bridal gowns often featured a fashionable sweetheart neckline and puffed sleeves. Bridesmaids’ dresses usually matched, and older bridesmaids wore short veils.

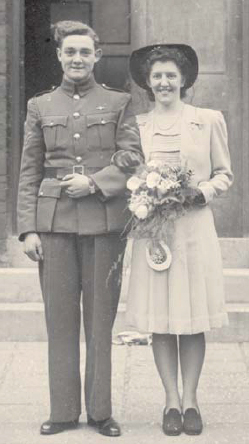

During the war it was usual for bridegrooms serving with the armed forces to wear military uniform on their wedding day. As the war progressed, many more women joined military units and support organisations, often meeting and marrying fellow servicemen. Women in the forces received no coupons for civilian dress, so a special bridal ensemble was usually out of the question and they too often married in uniform. At some wartime weddings both bride and groom wore full uniform and were attended by uniformed colleagues, often leaving the church under a ceremonial archway of swords, truncheons, even air-raid wardens’ helmets. Some prominent ladies were touched by the plight of servicewomen about to marry and arranged for at least some of them to enjoy a white wedding. The romantic novelist Barbara Cartland organised a pool of second-hand wedding dresses, which their owners agreed to sell free of coupons. Similarly, during a trip to London in 1944, the First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt, noticed the situation and on her return collected dresses and veils from American brides who had recently married and despatched them to Britain for loan to servicewomen. A Hollywood film studio also sent twelve beautiful wedding dresses to Britain – four for brides in each of the three armed services to borrow when their turn came, so that they could experience a sense of movie-star glamour on their special day.

Many wartime brides wore a smart civilian suit and hat, as seen in this wedding photograph from 1941. A horseshoe was a popular good-luck token.

Predictably, immediately after the war the popularity of weddings reached new heights. Until demobilised or while doing national service, bridegrooms continued to wear military uniform. Otherwise the average groom wore his ‘demob’ suit, a smart pre-war civilian lounge suit or, if he was fortunate, a new set of clothes, while many middle- and upper-class men revived the tradition of hiring a formal morning suit comprising dark tailcoat, grey striped trousers, a top hat, silk cravat and white gloves. With clothes rationing still in place, many post-war bridal dresses purchased or made in Britain retained their slender appearance, although modest trains reappeared and wedding outfits of the late 1940s began to display elements of the New Look. Some brides were lucky to be presented with beautiful dresses or fine materials from abroad, including wedding gowns from high-end New York department stores or lengths of lustrous Italian silk, by grooms who had served overseas during the war.

This couple were married at short notice in November 1944. The groom wears his airman’s service uniform and the bride a powder-blue crêpe dress adapted from a full-length bridesmaid’s dress, with a beaver-fur coat and smart accessories.

After the war, some grooms resumed the tradition of hiring formal morning suits and accessories from dress-hire firms such as Moss Bros, pictured in this 1946 advertisement.

The marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Prince Philip Mountbatten on 20 November 1947 was a glorious event that symbolised the ending of the bleak war years. The princess’s wedding gown, designed by Norman Hartnell, was fashioned from ivory silk satin from the Scottish firm Winterthur and encrusted with American seed pearls, while the 15-yard-long satin train was woven at Lullingstone in Kent. The dress bodice featured a fashionable sweetheart neckline and the long tulle veil was attached to a diamond fringe tiara, the whole ensemble achieving a perfect combination of femininity and glamour. Like all new wedding dresses in 1947, the royal gown required coupons and reportedly hundreds of brides-to-be throughout the country offered their clothing coupons to the princess.

The royal couturier, Norman Hartnell, designed Princess Elizabeth’s wedding gown, going-away outfit and bridesmaids’ dresses for her marriage in November 1947.