AFTER THE WAR, debt and inflation were matters of grave economic concern and the first year of peace seemed every bit as grim as the war years. The government tried to maintain the wartime ethos of sacrifice and compromise, but what many in Britain wanted above all was fun, freedom and a little luxury.

In 1946 a government-sponsored exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London called ‘Britain Can Make It’ attempted to revive the post-war design industry. London was struggling to maintain its fashion lead over Paris: there was no lack of British couture design talent, but progress was undermined by continuing shortages and delays in reverting back to peacetime production of civilian goods and the re-establishment of skilled textile and garment workers. Despite backing the London fashion industry, the authorities failed to understand the complex workings of international couture or to grasp the importance of reviving fashion at home to raise morale. The attractive export designs shown to foreign buyers were not available within the United Kingdom and served only to highlight the austerity of post-war Britain, where dress was still governed by rationing and price controls. Those women fortunate to find post-war employment outside the home soon discovered that their old Utility-style dresses and shoes were not considered suitable for smart shop or office work, yet they could not assemble a sophisticated working wardrobe on just a few coupons a month.

After the war, men too had to dress as best they could. Upon discharge from the armed forces, each serviceman was sent to a demobilisation centre for processing, where his military uniform and kit were exchanged for a ready-made ‘demob’ suit that aimed to equip him with a basic outfit for his return to civilian life. Choice was limited to a double-breasted pinstriped three-piece suit or a single-breasted jacket and flannel trousers. A felt hat or flat cap, two shirts, a tie, laced leather Oxford or Derby shoes and a raincoat completed each set produced for the War Department, and garments were sized and labelled in much the same way as military dress. Mass-produced, cut along Utility lines and on the whole ill-fitting and shapeless, the demob suit was widely regarded as yet another form of uniform and was generally unpopular. When men began to buy new suits again, younger males took a renewed interest in fashion. In time various styles began to be adopted, including the dandified velvet-collared overcoats and narrow trousers promoted by Savile Row tailors, that subsequently evolved into the Teddy boy image of the 1950s.

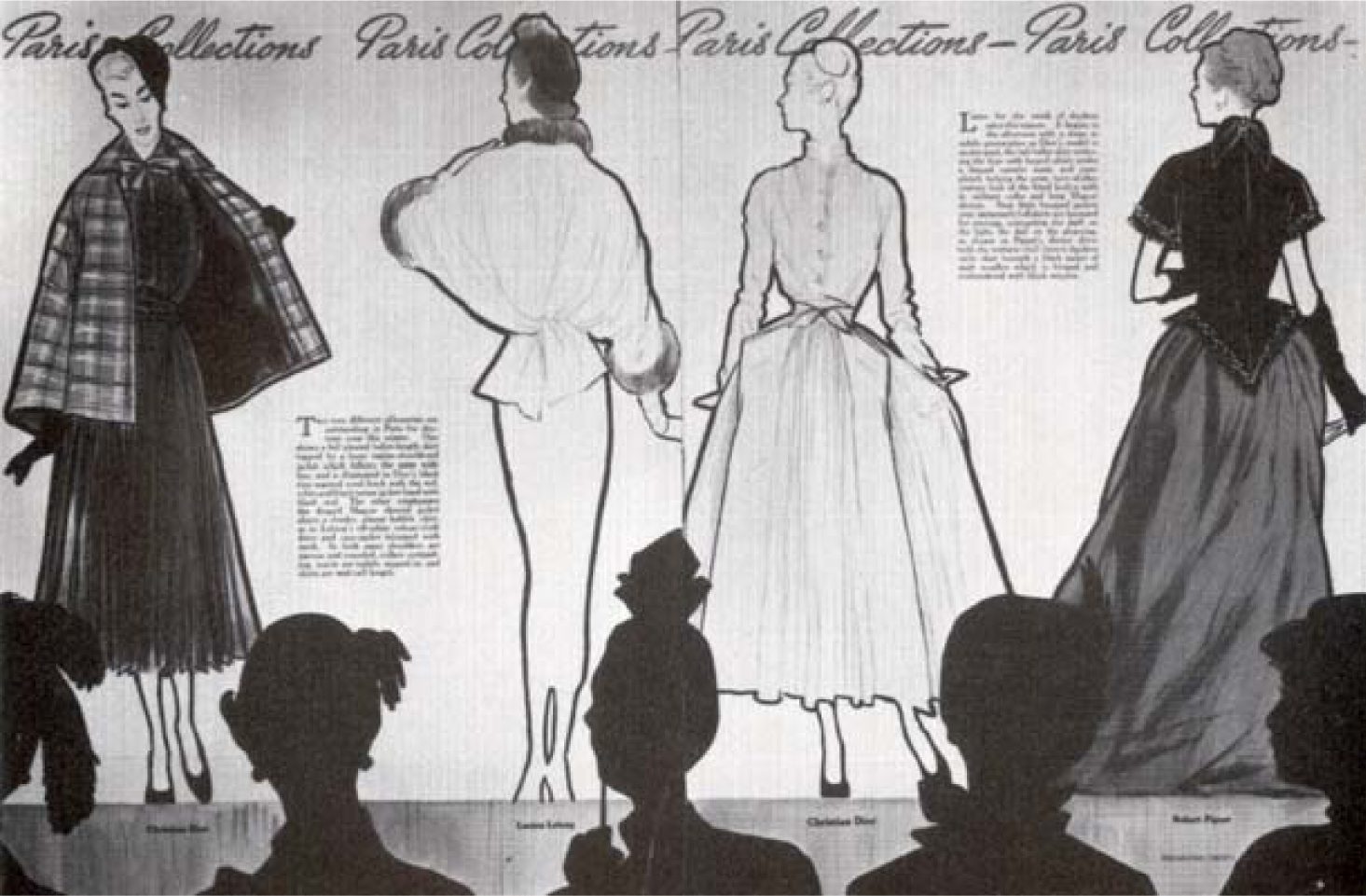

The New Look launched by Christian Dior in February 1947 revived nostalgic pre-war styles that accentuated the female figure.

For leisurewear after the war men often wore a sports jacket and loose flannel trousers, without a formal waistcoat or tie, as seen in this late-1940s snapshot.

When the so-called ‘New Look’ for women was launched in February 1947 by Parisian designer Christian Dior, a powerful sense of romantic nostalgia was introduced into the drab austerity of the post-war years. Characterised by a cinched waist, softly rounded shoulders, a prominent bosom and full, long skirt, the New Look was far from new, for the ‘corolle line’ – as it was first called – was heavily influenced by the feminine fashions of the mid-1910s and also by the mid-nineteenth-century crinoline. The silhouette had first been introduced in 1938/39, before the outbreak of war, chiefly for evening gowns, and had continued to evolve in Nazi-occupied France in the hands of French couturiers. Therefore Dior did not invent a new fashion as such, but developed existing themes, expertly transforming an ostentatious evening style into daring new day and afternoon outfits that surpassed anything seen in Britain for several years.

The sensational glamour of the lavish new costumes, which used many yards of material, initially met with a mixed reception in Britain. The government feared that such luxurious creations would herald economic disaster and asked the British Guild of Creative Designers to continue promoting shorter, knee-length hemlines, thereby conserving precious fabrics for the export market. Picture Post magazine, while admiring the beauty of the new fashions, wrote:

Paris forgets this is 1947. The styles are launched upon a world which has not the money to buy, the leisure to enjoy, nor in some designs even the strength to support these masses of elaborate material… there can be no question about the entire unsuitability of these new fashions, for our present life and times.

These New Look designs from Paris were featured in Woman’s Journal, November 1947. Dresses by Christian Dior, Lucien Lelong and Robert Piguet include day and evening wear and the alternative narrow-skirted version of the New Look.

Some women, too, objected to the excessive frivolity on economic and patriotic grounds, while others denounced the ultra-feminine silhouette, which required firm corsetry and padded busts and hips, as not only impractical for a modern lifestyle, but overtly anti-feminist – symbolic of the ornamental, indolent upper-class woman. However, British designers, such as Hardy Amies, who understood Dior’s approach, favoured longer skirts and argued that fashions emphasising women’s best attributes – ‘curved shoulders, high busts, small waists, full hips and a good carriage’ – would lead to better relations between men and women in the difficult period of acclimatisation following the war.

This guipière corset, designed in October 1947 by Marie Rose Lebigot for Marcel Rochas, constricts the waist and pads out the hips, creating the curvaceous silhouette that underpinned New Look fashions.

In the autumn of 1947 Dior showcased his collection in London and also demonstrated it privately to the royal family, Princess Margaret, especially, becoming a firm supporter of the new style. Princess Elizabeth wore the New Look on an official visit to France, where her elegance was reportedly admired by Dior himself, although after her wedding in November 1947 her going-away outfit, designed by Norman Hartnell, was a modest coupon-controlled dress in sky-blue crepe, with a matching velour coat and feather-trimmed hat. New Look collections emanating from Paris became progressively more extravagant and theatrical, with horsehair- and canvas-padded skirts and voluminous hemlines almost extending to ankle-length. Not surprisingly, some ordinary women saw the style as an essentially elite mode; however, the haute couture look was reinterpreted as affordable, attractive fashion and modified versions were being adopted in Britain by late 1947.

Magazines publicised the new line, suggesting ways of adapting existing garments, for example by adding inserts of material or tiers of extra fabric to the hems of frocks or lengthening fitted coats with bands of fur trimming. Ready-to-wear manufacturers disregarded government decrees, material shortages and rationing and created New Look copies, some garments being accurate imitations of Paris models, while others appeared as hybrids, retaining the familiar square shoulders but featuring a nipped-in waist and a longer, fuller skirt. By 1949 most shops were selling versions of the New Look and women could even copy the silhouette at home, using cut out and ready-to-sew dress patterns. Patronising though his words may sound to modern ears, Dior understood that: ‘To make a woman feel better, you must make her feel beautiful.’ For many the New Look did just that and it went on to become the predominant female silhouette of the 1950s.

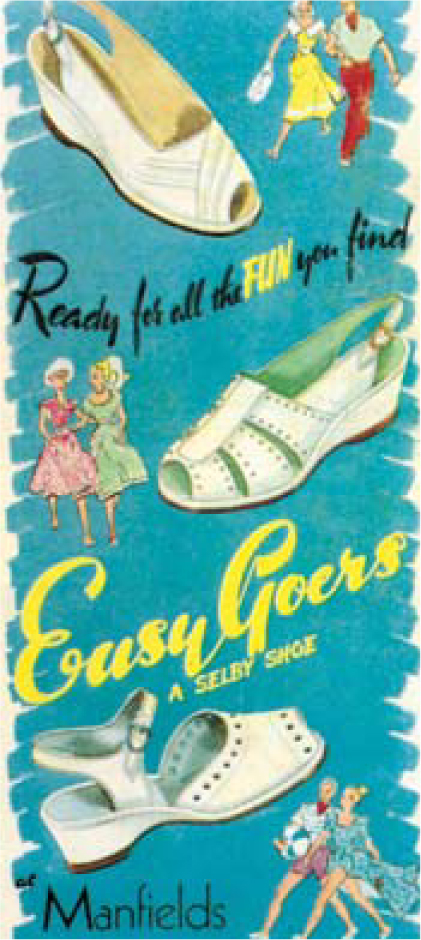

Ultimately the New Look succeeded in re-establishing Paris as the leading force in post-war international fashion, particularly at the couture level. However, it was the United States that spearheaded the modern approach to wearing clothes, with its emphasis on casual, sporting styles. British interest in American easy-to-wear clothing had been growing steadily throughout the inter-war era and innovative leisurewear from across the Atlantic continued to exert its influence after the war. Relaxed, interchangeable separates were essentially in tune with the comfortable skirts, sweaters, even trousers worn by many women during wartime, and after the war soft jerseys and tailored slacks were increasingly favoured by the young generation for weekend wear that was stylish, yet lacked the constraints of conventional dress. Footwear was also revolutionised in the later 1940s: gone was the need for sensible, hard-wearing leather shoes that would last for years, and new ranges of tantalising footwear appeared such as smart, low-heeled shoes pioneered by the American designer Claire McCardell, sling-back court shoes with peep toes and wedge-heeled or platform sandals with ankle straps – a popular style that also enjoyed royal patronage.

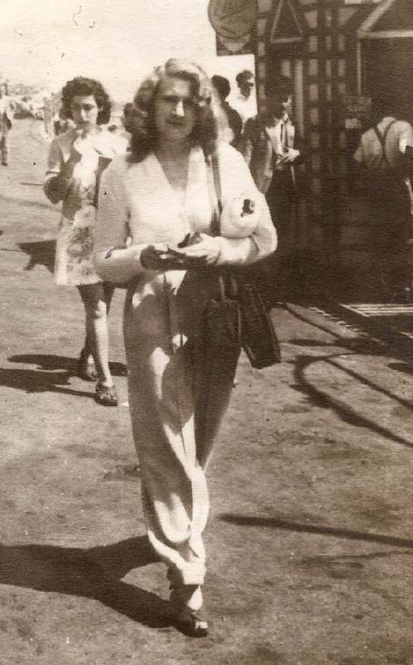

This teenager, photographed in 1947, wears a stylish fitted sweater and tailored trousers – modern post-war fashions influenced by American trends.

A late-1940s Manfields shoe advertisement demonstrates white summer sandals in fashionable peep-toe, wedge-heeled and sling-back styles.

Popular post-war beachwear included floral-print sundresses and playsuits, as seen in this snapshot taken in the summer of 1946.

Britain’s beaches had been closed to the public for much of the war, but, as they re-opened, holidaymakers flocked back to the coast for their summer holidays. July 1946 marked the official unveiling of the daring bikini, which bared the midriff, named after the American atom-bomb test on Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, although two-piece costumes had existed since the end of the 1920s. Some British women found the skimpier post-war bikini too risqué for comfort, but the glamorous corseted swimsuits of the later 1940s, featuring shaped stomach panels, boning and bra cups, were equally alluring. For the beach and general holiday wear, short strapless or halter-neck printed cotton sundresses and playsuits incorporating shorts were also becoming fashionable. Male swimwear usually comprised a pair of short-legged trunks, some styles featuring a webbing belt around the waist that gave a tailored effect. Crisp shorts and shirts and beach robes were fashioned in bright materials, reflecting a growing taste for colourful, casual American styles.

This alluring sea-green bathing suit fashioned with shaped panels and narrow shoulder straps is typical of late-1940s female swimwear.

An inextinguishable sense of glamour, determination and a powerful patriotic spirit had seen the civilian population through the years of deprivation, material shortages, clothes rationing and austerity fashion in 1940s Britain. The controversial late-decade New Look expressed a revival of pre-war decadence and luxury, while the young generation desired more casual, comfortable clothing styles. As the past came face to face with the future, diverse and exciting influences shaped the final phase of fashion during this unique and memorable era.

This Simpson’s advertisement from 1948 demonstrates the post-war vogue for men’s colourful beachwear, inspired by the bright sportswear being worn across the Atlantic.