1

An Introductory Overview of the Region

‘Nothing can well be more striking than the first view of Loch

Lomond: its spacious expanse of silvery water, its lovely islands, the

rich meadows and trees by which it is bounded, and the distant scene

of fading hills, among which Ben Lomond rears its broad and gigantic

bulk, like an Atlas to the sky.’

The Highlands and Western Islands of Scotland

John MacCulloch (1824)

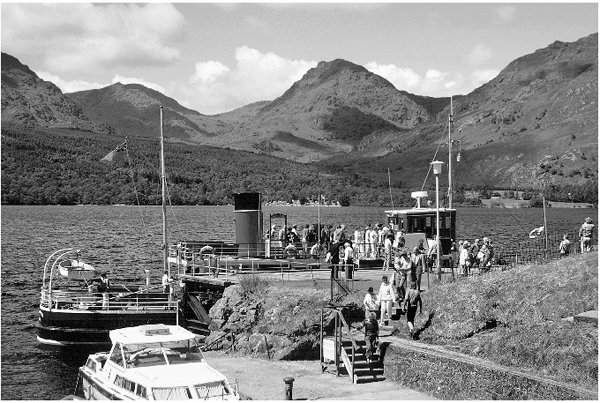

The main route from Glasgow to the western Highlands and Islands follows the glacially carved Loch Lomond Valley. As the city with its suburban sprawl is left behind and a view north to the Grampian Highlands gradually unfolds, first time visitors to Loch Lomondside are left in little doubt that this is the Scotland of their expectations – a country aptly described as a land of mountain and flood (Fig. 1.1). Over the centuries the loch itself has been known by several names, two of the earliest reflecting its well-wooded shores. Loch Lomond’s catchment is approximately 780 km2, but with the addition of the loch’s outlet to the Clyde Estuary, plus several other adjoining small areas that are essential to the story or add in some way to the historical and scientific interest of Loch Lomondside, the total coverage of the present regional study is nearer 800 km2.

Fig. 1.1 Admiring the beauties of Loch Lomondside by passenger boat has been popular with visitors for nearly 200 years.

For general locations and the many individual place names mentioned in this account, the recommended Ordnance Survey Sheet is the 1:25000 Outdoor Leisure 39 Loch Lomond, supplemented by Pathfinder Series sheets NS 47/57, 48/58, 68/78 and NN 22/33 covering southeast and north of the central area.

The loch and its catchment

By any yardstick Loch Lomond is very impressive. Shaped roughly like an elongated triangle, the narrow and deep northern half is typical of most Highland lochs, but its wide and relatively shallow southern end bears more than a passing resemblance to the island-strewn loughs of Ireland. Between the contrasting upper and lower portions of the loch lies a transitional zone, the Luss–Strathcashell basin. This central basin is bounded to the north by the Inverbeg bar and to the south by a close assemblage of islands between Bandry and Arrochymore Points, barriers that partially restrict the free circulation of water throughout the loch as a whole.

At 71 km2, Loch Lomond has the largest surface area of any water body in Britain. Most of the northern half of Loch Lomond is under 1.5 km in breadth, but it broadens out to a maximum of 6.8 km at its widest point in the south. Lomond’s 36.4 km length is outdistanced only by Lochs Ness and Awe. The greatest depth of water at 190 m in the loch’s over-steepened northern trench is exceeded only by Lochs Ness and Morar. Ness again is the only loch to outmatch Loch Lomond’s massive volume of water, the latter estimated in 1903 at 92,805 million cubic feet (2,628 million m3) during Murray and Pullars’ historic survey of Scottish freshwater lochs. From north to south, the main unimpeded rivers discharging into Loch Lomond are the Falloch, Douglas, Luss, Endrick and Fruin. The others – Inveruglas, Arklet and Finlas Waters – are impounded at some point by reservoir dams and, except following periods of heavy rain, are now mere shadows of their former selves. The River Leven is the loch’s only outlet. Despite the massive storage capacity of the Lomond basin lessening the effect of sudden surges of incoming water, at peak flow from the loch the Leven is understandably one of the fastest rivers in Scotland and provides a significant discharge of fresh water into the Inner Clyde Estuary.

With the extremely high annual rainfall experienced in the mountainous region of Loch Lomondside, the inflow from the northern catchment is twice that of the much larger southern catchment. Overall, it has been calculated (using pre-1970 rainfall figures) that in an average year, the total inflow is equivalent to an 18 m rise in loch level. With only the one outlet to the sea, autumn and winter peaks in precipitation inevitably lead to a severe imbalance between inflow and outflow, producing the occasional exceptional rise in the level of the loch and extensive flooding of adjoining low-lying land. Between 1770 and 1841, no fewer than four different schemes were promoted to lower the surface level by dredging the loch’s outlet, thereby alleviating winter flooding and improving the often waterlogged peripheral agricultural land. Nothing came of them because, in each case, not all the riparian owners were willing to bear their share of the cost. In the twentieth century an engineering project did go ahead; not to lower the water surface, but to impound the loch and raise its level as a major water supply for central Scotland. Prior to completion of the work in 1971, the modal loch level stood at 7.6 m Ordnance Datum, but this has since risen to about 7.9 m OD.

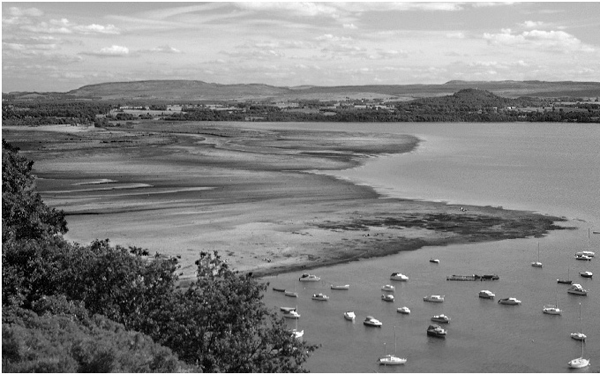

Fig. 1.2 The bed of the shallow southeast corner of the loch exposed during the drought of 1984.

The highest loch level on record of 10.05 m OD occurred in March 1990, following persistent rainfall over two and a half months, equal to almost three times the rainfall normally expected for mid to late winter. The lowest known loch level of 6.75 m OD was recorded in August 1984 (Fig. 1.2), after a period of below average rainfall that had lasted five months. These two extremes in surface level can be seen to differ by 3.3 m (almost 11 ft), possibly the greatest fluctuation of any lake in Britain, confirming once again that everything about Loch Lomond is on the grand scale.

On reading through a selection of descriptive accounts of Loch Lomond it becomes apparent that there is a lack of agreement over the number of islands or ‘inches’. Those with an eye to their financial value list only the larger habitable and cultivable islands, whereas others have inflated the figure by the inclusion of rocky islets, some of which are only exposed during low water. Taking a middle course by including only those islands with some permanent tree cover, regardless of economic worth or loch level, then the total stands at 39. Not that the number is static for all times; Inchmoan and Inchcruin were evidently the one island before a narrow isthmus eroded away. Wave erosion continues to play its part; the main body of Clairinsh is well on its way towards separating from its ‘fish-tail’-shaped southwestern end. Since the surface level was raised by the construction of a barrage across the loch’s only outlet, a small islet at the Endrick Mouth has been completely washed away. In contrast, Wallace’s Isle has been lost as an island by becoming firmly joined to the mainland shore through silting at the mouth of Inveruglas Water. Of Loch Lomond’s 39 islands with at least some tree cover, Inchmurrin at 116 ha is by far the largest, followed by Inchlonaig at 75 ha, Inchtavannach at 63 ha and Inchcailloch at 56 ha. Only two islands – Inchmurrin and Inchtavannach – are permanently occupied and farmed, although several other islands are seasonally occupied by residents and/or grazed by farm stock.

Fig. 1.3 A much enlarged Loch Arklet is incorporated into Glasgow’s water supply.

It would be remiss not to include in a description of the loch at least a brief mention of its famous three ‘marvels’ where fact and fiction merge:

Waves without Wind

Fish without Fins

and a Floating Island

Historians have puzzled over the marvels’ authenticity for centuries, yet there are plausible explanations for all three. ‘Waves without Wind’ are undoubtedly seiches. These can occur when a particularly strong wind suddenly drops, allowing the piled-up water on the windward side of the loch to move back in the other direction. To the casual observer, the waves now breaking on the opposite sheltered shore would appear to have no obvious cause. The duration of such water movement is usually short, but one exceptional seiche was timed oscillating back and forth for well over 12 hours. ‘Fish without Fins’ can be accounted for by the unusual presence in the loch of the river lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis) which, in the Highlands of Scotland, was once regarded as a creature of ill omen. A mat of loch shore vegetation breaking loose as the result of floods or a storm is not that rare an event; it is the size of these ‘Floating Islands’ that has been subject to gross exaggeration in travellers’ tales.

Because of its dominant presence in the landscape, Loch Lomond tends to overshadow the presence of other bodies of standing water in its catchment. In the early days of harnessing water power, a number of small lochans were enlarged to keep each district’s corn mill working when the rivers ran low. As the local demand for water increased, more substantial, entirely man-made reservoirs were constructed in the southern foothills to serve the developing industries and an expanding urban fringe. Later still, Loch Arklet (Fig. 1.3) and Loch Sloy in the high rainfall Highlands had their natural storage capacities massively enlarged for water supply and hydro-electric power respectively for consumers much further afield.

The native woodlands

Even before the appearance of early man with his grazing animals, axe and fire, the extent and composition of the native forest cover would have been ever-changing in response to the prevailing climatic conditions. Loch Lomondside is fortunate compared to most areas in the Scottish Highlands in retaining large stands of semi-natural broad-leaved woodland clothing the islands and the lower mountain slopes. This is no accident, but the result of several hundred years of sustainable coppice management designed to meet the raw material needs of industrial Clydeside, the oak woods in particular retaining some of their commercial value until the early twentieth century. Since then, these descendants of the ‘wildwood’ have faced an uncertain future, as most former coppice woodlands have been left open to grazing and browsing by farm stock, feral goats and deer. Replacement of broad-leaved trees by quick growing conifers and the invasion of many woodland stands by the widely planted non-native rhododendron (Rhododendron ponticum) have also taken their toll. A recent revival of interest in native woodlands on Loch Lomondside, more especially for their wildlife and landscape value, may yet tip the balance in their favour.

The uplands

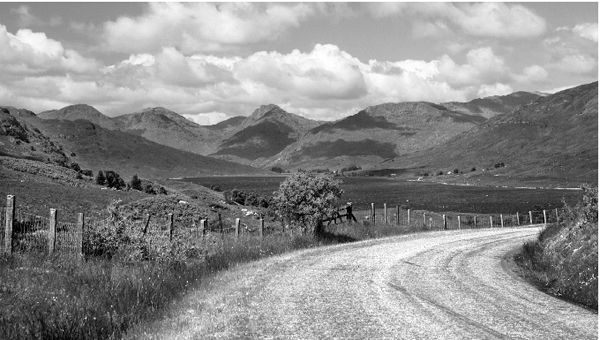

The land surrounding Loch Lomond ranges in height from near sea level to the 1,130 m (3,708 ft) peak of Ben Lui (Fig. 1.4), although because it is set apart, Ben Lomond at 974 m (3,194 ft) is the summit that first draws the eye. On the windswept and winter-frozen summit ridges of all the mountains approaching this height, only the hardiest life forms can survive all the year round. The Luss Hills on Loch Lomond’s southwestern flank are, by comparison, more gently rolling in character. Despite lacking the height and sculpturing of the northern peaks, these hills can still offer the keen walker over a dozen named tops above 2,000 ft (610 m). To the south of the Highland Line (a geographical boundary that marks out the Lowland/Highland divide in Scotland) Earl’s Seat at 578 m is the highest point of the Kilpatrick, Campsie and Fintry–Gargunnock Hills, which once formed a continuous plateau before being divided into three distinct blocks by glacial breaching.

Fig. 1.4 Ben Lui in the distance is the highest of the Loch Lomondside mountains.

For the most part, the uplands are covered in acidophilous vegetation, the region’s high rainfall having washed much of the natural fertility out of the soil. They have also been subject to intensive sheep grazing for over 250 years, which, together with an equally long history of regular burning, gradually transformed much of the former heathy cover to a sward of nutritionally poor grasses, with bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) covering large areas of the lower slopes. Now that the carrying capacity for high numbers of sheep on the Lomondside uplands is lost, large tracts of this degraded pasture have been planted with massive blocks of closely packed conifers, almost invariably foreign species.

Agriculture, industry and settlements

From the arrival of the early agriculturists to the advent of the Industrial Revolution, most of the inhabitants of Loch Lomondside were dependent on farming for their livelihoods. Once cleared of the forest cover, the soils of the low-lying land proved both fertile and workable for mixed farming, but on the less productive hill ground the accent was placed on the grazing of stock. Although land use continued to be dictated by the rhythm of the seasons, the early communal system evolved into individual farms, particularly during the period of agricultural improvement which began in the mid-1700s. One result of this change, which included the introduction of mechanised farm implements, was a lessening of the need for manpower, emigration of the people from the land further encouraged by the development of an industrial economy requiring a new workforce along the area’s southern fringe.

The rapid transformation of an inwardly-looking rural area to manufacturing and exporting on a world scale reflected the entrepreneurial spirit of the age. Away from the one-time sea port of Dumbarton at the mouth of the River Leven, whose initial industrial growth was based on glass making and shipbuilding, most of the centres of population in the low-lying agricultural belt of southern Loch Lomondside can trace their development as eighteenth to nineteenth-century textile villages taking advantage of the abundant supply of clean, fast flowing water in the manufacture and colouring of yarn and cloth. For Strathendrick and district, the employment opportunities brought about by the textile industry were short-lived, the switch to coal-fired steam power by competitors having rendered the more outlying water powered mills uncompetitive. Better placed, with more diversification of manufactories and closer links with centres of commerce on the River Clyde, the small industrial townships in the Vale of Leven continued to expand, so that today there is virtually no break in urban settlement between Dumbarton and Balloch on Loch Lomond’s southern shore. Over the last 50 years, the small settlements in the southeast of the region have all grown as dormitory villages to the centres of employment in the Glasgow conurbation.

By road, rail and water

As a tourist attraction, Loch Lomondside is unchallenged as the most popular countryside recreational destination in Scotland, in addition to its importance as the main through-route to the northwest of the country.

Up to the early 1930s, for a predominantly rural area, the southernmost part of Loch Lomondside enjoyed a comprehensive public transport system. Although bypassed by the main West Highland line, three other railway lines linked the centres of population; and despite having just lost its tramway connection between Balloch and Glasgow, faster and more flexible bus services were reaching even the most outlying villages. Paddle steamers based at Balloch still operated on the loch all the year round. Yet even as the expanding bus services led to the closure of two of the railway lines, the bus services themselves were facing increasing competition from the motor car. Initially, the west of Scotland was slow in taking up car ownership, but today the private motor reigns supreme.

Faced with nose-to-tail traffic on roads not designed for such a heavy volume of cars and commercial vehicles, considerable improvements have been carried out to the main A82 up the west side of Loch Lomond and again further north through Glen Falloch, necessitating the removal of earth and rock on a massive scale. Large swathes of deciduous woodland were cut down in the process. In other places the natural shoreline was embanked where the realigned road runs alongside the loch. Comparatively little road reconstruction work has been carried out on the east side of the loch, where the B837 goes no further than Rowardennan. On particularly fine summer weekends, the traffic congestion created by recreation seekers on this access route to the east shore of the loch (Fig. 1.5) can be such that it is not unknown for the road to be temporarily closed to all but local residents.

Fig. 1.5 In summer the shores of Loch Lomond can draw large numbers of recreation seekers.

The era of a few large pleasure steamers and work boats on Loch Lomond has given way to the age of small, high-powered craft; some permanently based, the rest trailer-borne day-to-day. Survey figures show that with increased leisure time the number of recreational powerboat owners taking advantage of the public right of navigation on the loch has been steadily rising year by year, with no upper limit set at the present time. The majority concentrate their activities in the southern half of the loch, in particular the shallow offshore waters which up to now have supported the greatest variety and abundance of lochside-edge and aquatic wildlife.

Loch Lomondside for the naturalist

The diversity of wildlife habitats to be found on Loch Lomondside, where the low country and the uplands meet, is unrivalled anywhere in central Scotland. Much of Loch Lomondside’s biological distinctiveness is owed to its close proximity to Scotland’s western seaboard, but with the region’s generally mild oceanic climate locally modified by high ground. This includes more than a dozen mountain summits over 3,000 ft (914 m). Such is the rapid fall in temperature and change in vegetation with increasing altitude, that with a little imagination the last part to the ascent of any of these high tops can become a journey back in time to an immediate postglacial age. Conversely, around the lochside edge and on the islands, the presence of the most expansive body of water in the country can ameliorate the effect of all but the severest winter cold. With such contrasting physical and climatic variations side by side, opportunities exist for a wide range of plants and animals within a relatively small area. In those parts subject to high rainfall the western elements of the British flora and fauna are well represented, but both northern and southern species commonly occur – a number of them reaching the limits of their geographical distribution in the British Isles. Not unexpectedly, the region holds the largest concentration of Red Data Book rare plants and animals of any district in Strathclyde. Add to this ready accessibility, and it becomes clear why Loch Lomondside has attracted the attention of both amateur naturalists and professional biologists over a long period.

In this work, for the purposes of describing such a varied flora and fauna, Loch Lomondside has been arbitrarily divided into four broad biogeographi-cal zones: the loch and surrounds, the Lowland fringe, deciduous and coniferous woodlands, muirs and mountains (Chapters 9–12). At species level, however, there can be considerable overlap between all four zones. No better example of adaptation to a wide range of ecological niches need be given than the wren (Troglodytes troglodytes), just about the smallest bird in Britain. On Lomondside, the wren not only finds a habitable spot in the reed beds alongside the lower River Leven’s intertidal waters, but in town gardens, parks, farmland, broad-leaved woodlands and conifer plantations, this tiny creature even managing to eke out a living amongst the jumble of fallen rocks around the summits of the highest mountains.