5

From Nomadic Hunter-Gatherers to Feudal Land Tenure

‘The past has no self-imposed boundaries. Prehistory slides into

history just as the medieval period merges imperceptibly with the

modern.’

Ancient Scotland

Stewart Ross (1991)

When man first left his footprints on the sandy shores of Loch Lomond is unknown, but it is assumed with reasonable certainty that exploration and finally settlement of this thickly forested inland territory came much later than around the more accessible western coastline of Scotland. Archaeologists have problems too in dating the successive periods of prehistory; for although each wave of new colonists added their own distinctive layer of occupation, the traces that have survived in the modern landscape are not only thin on the ground, but subject to overlap in time. Only with the dawning light of written history do events from the past become clearer.

The Mesolithic period

The scant remains uncovered so far of man’s earliest appearance on Loch Lomondside have been dated tentatively to around 6,000 years ago, towards the close of the Mesolithic period in Scotland. These Middle Stone Age people were essentially nomadic hunter-gatherers, travelling the waterways by dugout canoe from one temporary encampment to the next, as they followed the migratory movement of wild animals and the seasonal availability of edible plants in these northern climes. For the very first arrivals it is possible that Loch Lomondside only formed a summer hunting-gathering ground, retreating the short distance to the Clyde Estuary coast before the grip of an inland winter set in. In the absence of any remains of dwellings or funerary monuments, their fleeting stopping places have been identified only by the discarded fragments of stone hunting weapons and tools. Just a few of these encampments have been found: Duntreath in Strathblane, Shegarton in Glen Finlas and on one of the larger islands, Inchlonaig. Most of the implements recovered from these sites had been struck from locally obtained hard stone: jasper, lamprophyre, quartz, diorite, etc., but other materials found – flint and pitch-stone – were brought in from sources much further afield.

Apart from the limited use of fire, it is generally believed that the Mesolithic people had only a minimal impact on Loch Lomondside’s original wildwood; but with their successors came an increasing ability to modify the forest environment.

The Neolithic period

The arrival in the Clyde area about 5,000 years ago of the Neolithic or Late Stone Age people, with their goats, long-horned cattle, primitive sheep and the domesticated young of wild boar (Sus scrofa), heralded the earliest beginnings of a more sedentary way of life. Temporary cultivation patches within the more easily cleared upper birch forest were created by slash-and-burn, only to be abandoned within a few years once the natural fertility of the soil was spent. Although scrub would quickly close-in on these shifting agricultural sites, the Loch Lomondside pollen profiles of the period show increases in grasses, bracken and other plants associated with open and disturbed ground. For the first time wild creatures of the forest began to lose ground before the advance of man, some to disappear for ever.

Archaeological evidence is wanting on the wood and turf dwellings of the Neolithic period, which is characterised by more enduring stone-built chambered tombs. These communal burial vaults were covered over with loose stones, the elongated mounds known locally as long or lang cairns (Fig. 5.1). Ten or more chambered tombs have been identified in the southern half of the region, although all have been broken into or robbed of their covering stone. Apart from a very small number of polished stone axe-heads, picked up by chance at various localities throughout the Loch Lomond area, the only other site with possible late Neolithic connections is the Duntreath Standing Stones. Originally in a straight line running from southwest to northeast, the stones’ alignment matches up with a notch in the skyline of the Campsie Hills where the rising sun is first seen at the time of the equinox in spring and autumn.

The Bronze Age

The first people with the Celtic knowledge of metal working, initially with copper, but later in bronze, came to Scotland about 4,000 years ago. With the use of metal came the development of offensive weapons, from which can be inferred conflict between the tribes, possibly through competition for the most fertile arable and pasture land. The grouping of hut circles of late Bronze–early Iron Age in upper Strathendrick strongly suggests the increasing need for defence against attack. Yet this war-like race was also capable of producing the finest decorative pieces, especially in precious metals.

Like the preceding Neolithic settlers, the clearest evidence of these new people’s presence comes from their method of burying the dead, which evolved during the Bronze Age from communal to individual interment in slab-lined cists (pronounced kists). Above ground, the burial site may be within a circle of set stones or covered over by a rounded cairn of loose stones. Within the cist, the body was placed in a crouching position, often accompanied by handle-less food storage or drinking vessels. This funerary custom has given them the alternative name of the ‘Beaker People’. In the latter part of this cultural period, interment of the dead was superseded by cremation, and the ashes of the deceased were stored in a cinerary urn within the cist. At least 20 Bronze Age burial sites have been described for the area, some of them with multi-grouping of stone-covered cists. As agriculture expanded over the centuries, most of these cists were removed as obstacles to ploughing.

Stone carvings in the form of cup and ring markings began in the late Neolithic, but was taken a step further as rock art during the Bronze Age. The cup-shaped depressions, which are usually pocked into faces of flat stones, are sometimes surrounded by one or more complete or broken circular grooves. Few in number compared with the neighbouring Menteith area in the Forth Valley, these as yet to be understood symbols are for the most part found on fine-grained lavas and sandstones in the south, but examples are known from Highland rocks in Glen Finlas and near Inverarnan.

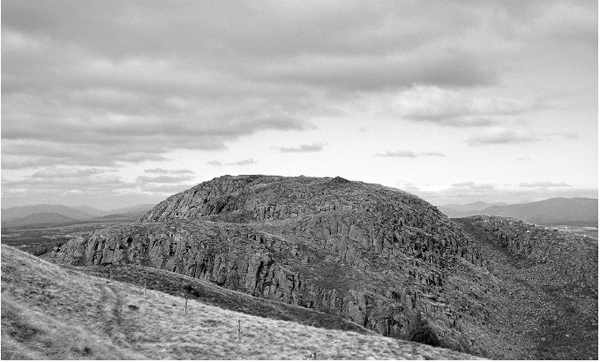

Fig. 5.1 A Neolithic burial cairn on the northern edge of the Kilpatrick Hills.

The Iron Age

In the wake of workers in copper and bronze came a people with the ability to fashion iron. Exactly when they extended their influence over or settled on Loch Lomondside is again uncertain, but it was probably about 2,500 years ago. For the archaeologist, the Iron Age offers more visual evidence of permanent settlement than just hut circles, burial chambers, standing and carved stones. The advances that took place in domestic and defensive building techniques can be classified into several different types – duns (pronounced doons), hill and peninsular forts, brochs and crannogs.

Duns are low, circular stone defences around individual homesteads, which for their small size have disproportionately thick walls of 3 m or more. For added protection they were frequently sited on steep-sided knolls. Loch Lomondside examples occur at Shemore in Glen Finlas and above Craigton in the Endrick Valley. The walls of Shemore dun are partially vitrified – the inner core of loose stone fused together in a solid mass – showing that the walls’ timber lacing has been burned, either by accident or design. Craigton dun is unusual in having been enlarged by the addition of an outer defensive wall. In an Iron Age context the term ‘fort’ is a misnomer, as it refers to little more than a huddle of dwellings and food stores protected by both inner and outer defences. Dunmore Hill (Fig. 5.2) above Strathendrick and Carman Hill overlooking the lower River Leven are typical high ground sites for such fortified villages. Strathcashell Point on the east side of Loch Lomond is the sole local representative of a peninsular fort, deep water on three sides providing the outer defence. Iron Age fortifications of increasing architectural sophistication came to the region with tall circular towers or brochs. Evidence of such a structure has been found at Craigievern near Drymen, with a confirmed example at Buchlyvie just outwith the Loch Lomond area. Excavation of the Buchlyvie broch – popularly known as the Fairy Knowe – has provided invaluable insight into the diet of Iron Age people in the region. Amongst the carbonised cereal seeds recovered, the most abundant by far is an early form of barley. Also present were the remains of wild boar and red deer (Cervus elaphus); hunting evidently still supplemented the meat from their domestic animals.

Fig. 5.2 Site of an Iron Age fort on the summit of Dunmore Hill.

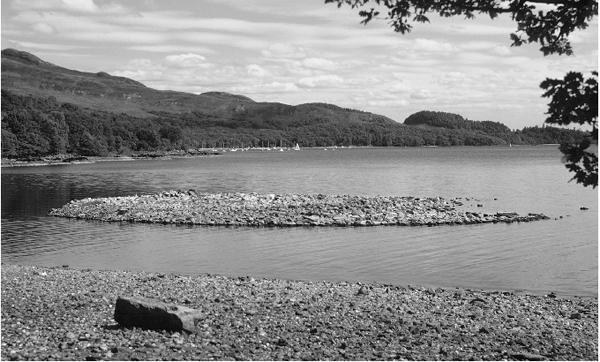

Perhaps because of climatic deterioration, farming shifted downhill to the oak forest-dominated ground, a move made possible because the land could be cleared with tree-felling axes of iron. With a paucity of natural defensive positions on the low-lying land, secure refuges were occasionally built in the loch itself. Known as crannogs, each of these islets of driven timber and sunken stone supported a platform with its wood and thatch dwelling raised well above water level. Because of the frequent winter storms experienced on the loch, most of these structures would have been sited in sheltered locations. Ten crannogs have been authenticated in the shallow waters of the southern and central basins of Loch Lomond. Others may have disappeared because they became convenient sources of stone to build jetties and breakwaters, or removed as hazards to navigation when deep hulled vessels were introduced to the loch. The stone base of the large crannog known as Swan Island is above the water surface for much of the year, but most, such as Strathcashell (Fig. 5.3), can be seen to advantage only when the loch level is low. At least one – Rossdhu Isle – continued its defensive role into medieval times, excavations showing that the crannog was re-used later as the foundations for a small castle. It is only in recent years with the development of new techniques in underwater archaeology that the layers of occupation on these man-made islands are being revealed.

Fig. 5.3 Foundations of the Strathcashell crannog exposed at low water.

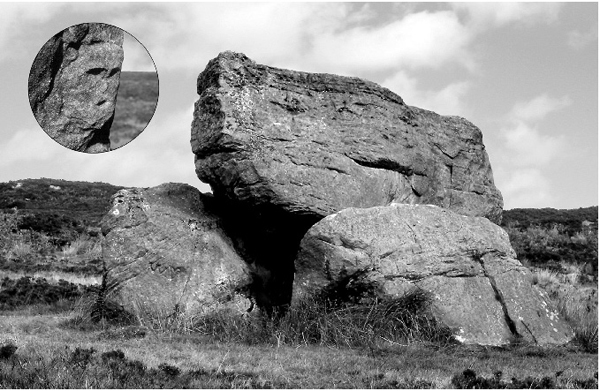

By far the most controversial relic of the period is the Auld Wives Lifts on Craigmaddie Muir. Set in an amphitheatre-like hollow, this weathered rock formation comprises two massive sandstone boulders supporting a flat-topped capstone of immense weight (Fig. 5.4). The name comes from a traditional story that tells of three old women or witches competing with one another over who could carry the largest stone. Even after dismissing the legend, agreement has yet to be reached on whether the three-stone arrangement is a naturally occurring glacial erratic, a monument entirely built by early Man, or perhaps a combination of the two. Even more intriguing are the nine human heads carved into the surface of the stones, rather curiously a feature unobserved by archaeologists until as late as 1975. One of the incised heads possibly represents the druidic horned god Cernunnos. Others suggest something altogether more sinister, the cult of the severed head. The mystery that surrounds the Craigmaddie Muir stones is still a long way from being solved.

Fig. 5.4 The mysterious stones of the Auld Wives Lifts on Craigmaddie Muir.

Throughout Britain as a whole, historians consider that this last prehistoric age was brought to an end by the full-scale Roman invasion of AD43. Iron Age society north of the Forth–Clyde line (which was only briefly within the influence of Imperial Rome) continued long after that date. Indeed, it could be argued that the custom of moving home and animals up to the high ground in summer, which persisted on Loch Lomondside right up to the end of the eighteenth century, can be traced back to Iron Age pastoral practices.

The Roman occupation during the Flavian period

In AD79, four Roman legions and auxiliary troops under the leadership of Gnaeus Julius Agricola moved into what is now Scotland, their objective to extend Rome’s claim over the whole island province of Britannia. With the invasion of North Britannia or Caledonia came the very first written accounts of actual events, although some of the dates set down in the texts are not always as precise as historians would like. According to Tacitus, Agricola’s son-in-law and biographer, the invasion force first consolidated its hold over the southern territories by establishing praesidia (garrisons) across the Forth–Clyde line. Following a further advance north and a victory of little lasting result against the gathered tribes in AD83, the Roman army constructed a string of forts just to the south of the Highland Line. Beyond, so Tacitus tells us, lay ‘perilous depths of woods’ – the Caledonia silva or Caledonian Forest of the Ptolemy manuscript map. Strategically, the sites chosen for the forts would have been on open, defensible ground already cleared of its cover of trees. The loss of three legions ambushed in Germany’s Teutoburg Forest 70 years earlier was never far from the minds of Roman commanders.

On Loch Lomondside, towards the western end of the new frontier, Drumquhassle was chosen for building one of the Highland Line forts. The presence of a Roman fort on Loch Lomondside had been suspected for some time, but the site at Drumquhassle (which significantly translates into castle or fortifications on the ridge) was not located until the summer of 1977, when the outline of the structure was picked up by aerial photography as faint crop marks in the drying top soil. Sited on a high vantage point to the southeast of the present village of Drymen, Drumquhassle bears all the hallmarks of Roman military planning. The size and layout of the fort’s inner and outer defences suggests it was capable of accommodating up to 500 frontline fighting men, but in practice was probably held by a much smaller force of auxiliary troops that could be reinforced as required. There is evidence to suggest Drumquhassle was linked by road to the next fort to the northeast at Malling near the Lake of Menteith in the Forth Valley and, in the opposite direction, by a supply route from the probable but yet to be identified base camp overlooking the former Dumbuck ford across the River Clyde. It seems likely these ‘Roman roads’ were cross-country trade routes or local trackways already ancient before the legions arrived on the scene, although sections of them would have been improved by army engineers.

Whether Drumquhassle (together with the other Highland Line forts) was primarily intended as a containment of the still troublesome Caledonii or as a springboard for the final conquest of the Highlands is uncertain, for in AD86 or 87 the fort was dismantled after only a few years of use, when the occupying Roman forces abandoned much of Scotland to deal with more pressing problems nearer home.

The Roman army did eventually return to the Forth–Clyde line just over a half a century later, completing a more permanent defensive frontier – the Antonine Wall – across the waist of Scotland by AD142. The wall was held against the northern tribes for about 20 years before another and this time final withdrawal south. Although no doubt visited by the occasional forward patrol, the Drumquhassle fort that had once stood sentinal over the furthest flung corner of the Roman Empire, was not re-occupied during the Antonine period.

The three kingdoms

With the abandonment of North Britannia by Rome, there followed a period of several hundred years described by historians as ‘the Dark Ages’, in which even important events are shrouded from us. What is certain, however, is that the many disparate tribes that had formerly occupied west–central Scotland were superseded by three supra-groupings or ‘kingdoms’ of old and new peoples – the Britons, Picts and Scots.

The Britons, who were the successors to, if not descendants of, the tribal Damnonii encountered by the Romans, occupied Alcluith or Alclut, their dominion taking its ancient name from the ‘Rock of the Clyde’. In the region now referred to as Strathclyde, Loch Lomondside formed the northernmost part of the Britons’ territory, and the towering rock at the confluence of the Rivers Leven and Clyde (Fig. 5.5) became known as Dun Breatann – the ‘Fortress of the Britons’; a seat of kingship, a centre for ship-borne trade and a place among the larger-than-life Arthurian legends. To the northeast of Loch Lomond stretched the kingdom of the Picts, the direct descendants of the Caledonii who had so stubbornly resisted Roman expansion further north. To the west lay Dalriada – the kingdom of the Scots, a people with cultural links to Ireland. Tradition has it that the Clach nam Breatann (the Stone of Britons) in Glen Falloch formed a boundary between the three kingdoms. If this story has any substance, it seems feasible that the uneasy frontier between the lands of the Britons and the Gaelic-speaking Scots continued southwest from Clach nam Breatann to Cnap na Criche – the boundary hillock – at the head of Glen Sloy, then on to another large stone, Clach a’ Breatannaich, near Lochgoilhead in Cowal.

Even as the balance of power ebbed and flowed, the unifying influence of Christianity as it spread throughout the three kingdoms was beginning to make itself felt. The Christian gospel first reached Loch Lomondside through St Kessog from southern Ireland, who settled in the Luss area during the early sixth century. His evangelical mission is commemorated in the name Inchtavannoch or Monks Island. Others of the Celtic Church were to follow in his footsteps in the early eighth century – St Kentergerna and St Ronan – associated with Inchcailloch (island of the cowled women or nuns) and Kilmaronock (Church of St Ronan) respectively. The first step in the emergence of a single nation was the integration of the Picts and Scots, with Kenneth, son of Alpin, becoming ruler over the combined kingdom of Alba by AD842. The two kingdoms had already allied themselves with the Britons against common enemies earlier in the century; and when Malcolm II of Alba died in 1034, he was succeeded by his grandson Duncan (of Shakespeare’s Macbeth), king of Strathclyde, thereby uniting all three kingdoms for the first time.

Fig. 5.5 The Dark Ages settlement on Dumbarton Rock is reputed to have been the northern capital of the legendary King Arthur of the Britons.

There had, of course, been other contenders for dominance over west–central Scotland. On at least one occasion a combined force of Northumbrians and Germanic Angles from the east overcame the defensive heights of Dumbarton Rock, but it was the ‘fury of the northmen’ that posed the most serious threat to the stability of the region for about 400 years.

Viking raids

History is silent on how many times the Viking longships came up the Clyde Estuary bent on a seaborne raid. On one such assault in the year AD870, Olaf the White, the Norse king of Ireland, laid siege to the Britons’ stronghold of Dumbarton Rock. The defenders held out for four months before their capital was overrun and sacked.

Scotland’s struggle for national sovereignty and Norse territorial claims for the Northern and Western Isles and elsewhere along the coast came to a head in the mid-thirteenth century. In the autumn of 1263, an assembled fleet of war galleys, under the direct command of King Haakon of Norway, arrived in the Clyde Estuary to deliver a decisive blow. According to the Haakonar Saga, a squadron of the smaller boats broke away from the main fleet and sailed to the head of Loch Long. With their stone ballast removed, the lightweight, shallow-keeled craft were dragged overland on timber rollers across the narrow neck of land (Fig. 5.6) separating the sea from Loch Lomond. Having thus successfully bypassed the heavily defended Dumbarton Rock that protected the only navigable entrance from the sea into Loch Lomond, the raiders put the lochside and island settlements to the fire and sword, before going on to make a strike further east into Scotland’s heartland. Laden with plunder, this small invasion force returned to sea the way they had come. Delayed by storms in Loch Long, they arrived too late to play any part in the action between Haakon’s main forces and the Scottish army which confronted the invaders at Largs on the Ayrshire coast. A peace treaty between King Haakon’s successor and Alexander III of Scotland was signed less than three years later at Perth in July 1266, bringing several centuries of savage onslaught by the Norsemen to an end.

Probable evidence of the 1263 sacking of Loch Lomondside comes from a Viking warrior burial site discovered in 1851 near the mouth of the River Fruin. Within the burial mound the remains of a Scandinavian-type sword, a spear head and the centre boss of a shield were found. Contrary to popular belief, the so-called Viking stone – a decorated hogback tombstone in Luss kirkyard – has no direct connection with the Haakon raid, most likely representing an outlier of Norse culture from their settlements in southwest Scotland.

The great Earldom of Lennox

Scotland at the time of the Treaty of Perth was quite a different country from the one the Vikings had first encountered during their earliest incursions, the change attributable in part to Anglo–Norman influence from the south. It would be difficult to be precise over the date when the move away from Celtic tribal culture began, but an important turning point was the marriage of Malcolm III to his second wife Margaret, an Anglo-Saxon princess who had fled to Scotland with her family following the Norman Conquest of England. Shortly after King Malcolm’s death in battle in 1093, the throne was seized by his exiled brother Donald Ban, who became the last Celtic king of Scotland. Queen Margaret’s half-English sons Edgar, Alexander and David made their escape to England initially for reasons of personal safety, but by acknowledging William II (William Rufus) and his successor Henry I as their feudal superiors, they received military backing for regaining the Scottish throne. Donald Ban was finally overthrown in 1097, all three brothers that had fled to England becoming kings of Scotland in turn.

Fig. 5.6 The close proximity of Loch Lomond to Loch Long in the Clyde Estuary can best be seen from high ground.

The way Scotland was governed changed dramatically during the reign of David I (1124–1153), who had spent over 30 years in England before succeeding his elder brothers. During this time he had acquired by marriage vast estates in the east midlands of England, and was well practised in the Norman feudal system of landownership and patronage.

One of the first great lordships to be established in Scotland on the Norman principle of land tenure confirmed by charter was the hereditary Earldom of Levenax or Lennox. Dating from the twelfth century, the Lennox encompassed what was to later become Dunbartonshire and West Stirlingshire, which included virtually the whole of Loch Lomondside. The early history of the Lennox is obscure, but among the first of the earls was one of David I’s grandsons, better known by his later title of Earl David of Huntingdon. Sometime in the 1190s, the earldom passed to the Scottish line of overlords, who had by then satisfactorily demonstrated their allegiance to the new regime. The backbone to the system was power through force of arms. Although the main stronghold was the royal castle at Dumbarton, the Loch Lomondside portion of the Lennox had a network of up to 20 smaller ‘castles’ that were held by the Earl’s kinsmen and other supporters. The Earl’s own castle originally stood in what is now Balloch Country Park, but at a later date a move was made to a more easily defended island castle on Inchmurrin. When first built, each of the smaller fortifications throughout the Lennox comprised a palisaded wooden tower sited on a natural or artificially raised mound, usually surrounded by a defensive ditch. Although little more than the earthworks remain, Sir John de Graham’s castle at the head of the Endrick Valley is one such ‘motte and bailey’ castle. In time these wooded structures evolved into stone-built towers or keeps; Culcreuch at Fintry and Duntreath in Strathblane (Fig. 5.7) are well-preserved examples. In addition to the Grahams, some of the oldest family names connected with landowning on Loch Lomondside can be traced back to the Earldom of Lennox, including Buchanan, Colquhoun, Cunninghame, Drummond, Edmonstone, Galbraith, Lindsay, Napier and of course the surname Lennox itself.

Important administrative changes occurred in the Lennox during the reign of Alexander II (1214–1249). First was the raising of Dumbarton into a royal burgh in 1222, which conferred on the town’s traders and craftsmen certain privileges and monopolies, exemption from toll and custom charges, and the right to hold a weekly market or fair. This was followed about 1238 by the setting up of a sheriffdom centred on Dumbarton, considered essential to maintain royal authority and control. From that time onwards, the castle and burgh of Dumbarton were excluded from the Earldom of Lennox. In addition to acting as keeper of the castle, the appointed officer was responsible for the military and judicial functions of government in the region, together with collecting the king’s revenues. Geographically, the Dumbarton sheriffdom followed much the same boundaries as the Lennox, but during the fourteenth century the western Strathendrick portion, which takes in Buchanan, Drymen, Killearn, Balfron, Strathblane and Fintry, was transferred to the sheriffdom of Stirling. Another tier of administration and revenue raising came from the reorganised church, with the gradual establishment of a diocesan and parochial system from the mid-twelfth century. Payment of teinds or tithes (one tenth of all produce) to the parish church became enforceable by law. Successive Earls of Lennox were particularly generous to the Abbey of Paisley just across the River Clyde, with grants of lands in the Kilpatricks along with specified rights on Loch Lomondside and the River Leven for timber extraction and fishings.

Fig. 5.7 A well-preserved medieval defensive tower at Duntreath, Strathblane.

The end of the Lennox dynasty came with the execution of Duncan, the 8th Earl, at Stirling Castle in 1425, because of his allegiance to Regent Albany rather than the absent King James I. The Earl’s daughter Countess Isabella (married into the Albany family) was imprisoned for a time, but on release was allowed to live out the rest of her days at the island castle of Inchmurrin. In the absence of male heirs, the break-up of the great Earldom of Lennox began with her death around 1460.

Inheritors of the Lennox

An account of the rise and decline in the fortunes of the Loch Lomondside landowning families after the partition of the Earldom of Lennox would warrant a book in itself; only a very short summary of some of the connecting threads can be given here. The latter part of the period also saw the gradual disappearance of the fortified tower house and the emergence of the country mansion set within its laid out parkland and policy woodlands.

Two ancient Lennox families in their ascendancy were the Colquhouns of Kilpatrick and the Grahams of Mugdock. In the fourteenth century the Colquhouns merged by marriage with the heritors of the lands of Luss, which with their subsequent acquisitions took in virtually the whole of the west side of Loch Lomond. The Grahams, who also adopted the name Montrose from lands granted to them on the east side of Scotland by Robert I, extended their possessions up the east side of the loch by the purchase of the Laird of Buchanan’s estate in the late seventeenth century, acquiring almost immediately afterwards what remained of the original Earldom of Lennox. Although Buchanan of Buchanan’s extensive estate had been dispersed, another branch of the family – Buchanan of Drumakill – took over the lands of Ross to the south of the loch. Other Lowland families with large estates included the Napiers of Gartness, Ballikinrain and Culcreuch, the Edmonstones of Duntreath and the Smollets of Cameron and Bonhill.

Only one Highland family of the Lennox emerged as a major landowner – the Parlanes or Macfarlanes – who held all the mountainous ground between Inverbeg and Inverarnan. Most of the Macfarlane clan territory was disposed of in 1785, subsequently to be purchased by the Colquhouns in 1821. Just to the north of Loch Lomondside lay the lands of Campbell of Glenorchy, which in time were extended throughout much of Perthshire and Argyll to become the largest feudal landownership in Scotland. It was during the time of Sir Duncan (‘Black Duncan’) Campbell of Glenorchy that Glen Falloch Estate fell into his family’s hands in 1598.

The last hundred years has seen a reversal in the fortunes of Loch Lomondside’s long-established estates, as successive inheritors’ liability for payment of high death duties on their properties could only be met by selling off tracts of land.

Clan MacGregor

This chapter would not be complete without mention of the brief occupancy of part of Loch Lomondside by Clan MacGregor, not least for the worldwide interest in the romanticised adventures of Rob Roy MacGregor as portrayed by Daniel Defoe, Sir Walter Scott and many others. For centuries the MacGregors had held on fiercely to their ancestral lands in central Scotland, not by feudal charter but by right of sword. But powerful enemies gathered against them, leading to the clan being dispossessed and scattered, and even their very name proscribed. Their support for the royal house of Stewart did see a temporary upturn in the clan’s fortunes following the restoration of Charles II in 1660. The first to become a landowner in the Loch Lomond area, Gregor Oig MacGregor, acquired Corrie Arklet from the Buchanans about 1661. Then in 1693 the newly installed chief of the clan, Archibald MacGregor of Kilmannan, purchased Craigrostan from the Colquhouns of Luss, turning over the Inversnaid portion to his close kinsman, Rob Roy. By 1706, all of Craigrostan was in Rob Roy’s possession. This, together with the acquisition of Ardess in 1711, made him a not inconsiderable property owner on the east side of the loch. Many landless families of the MacGregor clan were encouraged to settle the ground. Local apprehension at the build-up in the number of incoming Highland clansmen loyal to Rob Roy was to prove well founded, for armed parties of MacGregors swooped down to pillage their southern neighbours during the turmoil of the Jacobite uprising of 1715. The government responded by annexing Rob Roy’s estate and establishing a permanent military presence at Inversnaid (Fig. 5.8).

Fig. 5.8 A garrison of soldiers was established at Inversnaid after the 1715 Jacobite uprising (Author’s collection).