7

Industry, Water Supply and Hydro-electric Power

‘No sound of wheel

Turning with flash of spray comes from the mill,

Its voice of toiling now is hushed and still.

The window panes

Are broken, and the oaken doors

Stand open to the rains,

And moss grows green upon the rotting floors.’

Newton Mill

Anon (1928)

From earliest times the inhabitants of Loch Lomondside had made use of its land and water resources to meet little more than their own requirements. This way of life was to change forever with the advent of mechanisation and the ability to mass produce. Improved communications opened up new markets for mill and factory-made products, some of them worldwide. With industrial growth came the concentration of a large proportion of the local population into towns and textile mill villages, paradoxically creating new pressures on the surrounding countryside, in particular as a dependable provider of clean water on demand. Despite the high annual rainfall in the region, this need could only be met by the construction of storage reservoirs. Energy consumption rose in parallel, progressing from water power to fossil fuels; and, in the second half of the twentieth century, to hydro-electricity, which necessitated further water diversion and storage on a large scale.

The industrial era

Textile manufacturing

Until the eighteenth century, the rural textile industry on Loch Lomondside served only local needs, producing linen (from home-grown flax) and woollen cloth. The first sign of change came in the 1720s, with government premiums available to perfect machinery for separating out the flax fibres, which were then combed and spun into linen thread. Grants were also made available to set up the large open bleachfields needed to whiten the greenish-grey cloth that the flax produced. Thereafter the picture was one of continuous development and expansion using imported raw materials, linen manufacturing slowly being replaced by cotton.

From 1707, the Treaty of Union between Scotland and England had greatly facilitated Scottish trade with the English colonies in North America and the West Indies, with the Glasgow merchants taking full advantage of their west coast proximity to the direct Atlantic routes. Fortunes were made by importing tobacco and sugar, and much of the new capital created was used to diversify into textile production. There was a number of good reasons for establishing the new textile manufactories away from Glasgow itself, not least the available labour pool made up of those displaced by the sweeping changes in rural land management and tenure. Fast-flowing upland rivers and streams could be harnessed to power the spinning, weaving and later, cloth-printing machines, as well as provide the copious supply of soft water needed to both bleach and dye. There was yet another benefit to be gained from the region’s wet climate, for the high humidity encouraged the cotton fibres to cling together during the spinning stage, reducing the risk of breakage when the yarn was under strain.

The first of several commercial bleachfields on the River Leven’s flood meadows was established in 1715. Unbleached linen cloth was soaked with water from a network of channels before being laid out to dry in the sun, the process repeated at regular intervals over the course of several weeks. Long after open-air bleaching was abandoned in favour of synthetic agents, which could whiten the linen cloth indoors in a matter of days, the word ‘field’ persisted in the names of the Vale’s dye and print works. Although spinning and dyeing of linen thread had been mechanised, it was to be some years before techniques became available for the factory dyeing of already woven cloth. The first printworks able successfully to apply colour to cloth became operational in 1768. This period of textile dyeing and printing also produced the first reported incidents of industrial pollutants discharged into the River Leven, seriously damaging the fishings. On the east side of the region, releases of industrial effluent from a print works established beside the River Blane also proved harmful to fish stocks.

By the turn of the nineteenth century there were up to six print works and five bleachfields concentrated in a 5 km stretch of the River Leven, between them employing some 3,000 men, women and children, their output confined almost exclusively to the finishing stages in the treatment of bought-in cloth. Strathendrick’s textile industry revolved more around the initial processes of spinning and weaving. With the price of linen steadily rising and the repeal of protectionist legislation that had acted against cotton cloth, by the mid-eighteenth century the latter had become the cheaper of the two materials. To meet this new opportunity, cotton-spinning mills were erected during the 1790s at Balfron and Fintry (Fig. 7.1) alongside the River Endrick, with reservoirs constructed to provide additional headwater during the drier summer months. In both locations, company houses were specially built to house the influx of workers. Balfron, the largest concern, employed 400 factory workers engaged in spinning, with an equal number of outworking hand-loom weavers producing the cloth in their own homes. But barely had these water-powered mills become fully operational, than cotton processing by coal-fired steam power was introduced elsewhere. Conversion to steam power was not a practical proposition in the Endrick Valley because of the distance from the nearest source of coal. It was these same enterprises that were hardest hit by the general trade depression that followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the adoption of power loom weaving in other parts of industrialised Scotland. The cotton famine brought about by the American Civil War (1861–65) was to prove the last straw, and by the end of the century all of the outlying mills had closed down. One lasting legacy of this rural industrial age, however, was the improvements carried out on what had been up to then very rough country roads.

Fig. 7.1 An abandoned cotton mill at Fintry in Strathendrick (Author’s collection).

Although the Vale of Leven’s dyeing and printing industries had been similarly depressed by the American cotton shortage, they quickly recovered once supplies were restored, at peak production employing between them some 6,000 people. With auxiliary steam power installed and mechanical cylinder printing replacing all but specialised block printing by hand, the output of finished cloth greatly increased. The Vale printworks became the country’s leading exponents in the use of Turkey red, a dye noted for its vividness and ability to withstand strong sunshine without fading, essential qualities needed for the intended markets in the Far East. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the various dyeing and printing works in the area found themselves struggling against increasing competition from abroad and technical advances made by rival concerns in the north of England. Even with a rail transport link, the last outlying printworks at Blanefield had ceased production by 1898. In the Vale, amalgamation into one large company slowed down the decline for a time, but one by one the Vale works closed their doors. A brief respite came with the opening of a silk-dyeing factory at Balloch in the early 1930s, but when this was wound up in 1980, it brought to an end the textile industry which had been the mainstay of the Vale of Leven’s economy for some 250 years.

Glass-making and ship building at Dumbarton

Dumbarton’s early history as a seaport trading with England and the Continent owed much to the presence of a gravel encrusted shoal that stretched across the Clyde Estuary just upstream of the town, preventing the further passage of all but the smallest boats. But once a navigable channel had been dredged through ‘the grand obstacle’ in the 1780s, giving fully laden sea-going vessels access to the very heart of Glasgow, Dumbarton’s importance for handling overseas trade went into decline. With the lower tidal reaches of the River Leven too saline and turbid to be of use in the textile industry, Dumbarton instead turned to the manufacture of glass and the building of ships.

Fig. 7.2 Seen from above the town, the Dumbarton glass works in full production (Dumbarton Libraries collection).

The setting up of a glass-making company in Dumbarton took place in 1776, making use of a large sandbank near the mouth of the Leven for its raw material. The necessary potash came from burnt seaweed imported from the Western Isles. Three cone-shaped glass furnaces, which were said to have been the largest in Scotland, were a conspicuous feature of the town’s skyline (Fig. 7.2), often remarked upon in travellers’ accounts. Dumbarton specialised in high quality crown glass, produced by revolving the molten material into circular discs from which small window panes were then cut. Apart from a short break in the 1830s, glass-making at Dumbarton continued until about 1850, when closure of the works followed the removal of the duty on cheaper glass imported from abroad.

Ship building on the lower River Leven dated back at least to the time of Robert I, the Loch Lomondside woods meeting much of the early industry’s requirements for timber. It was not until the transition from wood to iron in the nineteenth century that the Dumbarton yards really came into their own, to their credit introducing several ‘firsts’ in ship design and construction as sail power gradually gave way to steam. Pioneering in service too, for it was the locally built Margery that became the first ever steamship to cross the English Channel. Some idea of the upsurge in ship building activity at Dumbarton can be gauged from a published list of more than 360 vessels built during a 20 year period between 1839 and 1859. Over the next two decades, 16 different yards were engaged in building and refitting ships, with allied trades such as foundries, rope works, sail and boiler makers giving further employment in the town. Whereas the textile factories in the Vale lost out as a result of the American Civil War, ship building on the Leven was given an additional boost with orders for fast blockade runners from the southern states. The local yards played an important role in the creation of the largest inland waterway fleet ever assembled – the Irrawaddy Flotilla in Burma, immortalised in verse by Rudyard Kipling in his Road to Mandalay. The venture earned Dumbarton a permanent place in the annals of ship construction, with well over 400 shallow draft vessels destined for the riverboat trade built in kit form by one company alone. An individual inland steamer worthy of special mention is the Coya, which was built at Dumbarton in 1891 before being taken apart and the sections shipped off to South America. There it was reassembled and launched on Lake Titicaca, 3,960 m up in the Peruvian Andes, the vessel giving service for over 80 years.

The prosperity that ship building brought to the town was not to last, a gradual closure of the Dumbarton yards reflecting a national decline in the industry. Despite having diversified into roll-on/roll-off ferries and hovercraft, the last surviving large company – Dennys – ceased trading in 1963, but with an outstanding record of having built some 1,500 passenger, merchant and warships. The most celebrated vessel to come from a Dumbarton ship building yard is undoubtedly the fast tea clipper Cutty Sark (Fig. 7.3), which was launched in November 1869. After falling on hard times, this now restored merchantman is exhibited at Greenwich in London, an evocative reminder of the last great days of sail.

The motor, munitions and aircraft industries

At the height of industrialisation, there were, of course, other major manufacturies in Dumbarton and the Vale of Leven apart from textiles, glass-making and the building of ships. Vintage motor enthusiasts will not need reminding of the Vale’s connection with the renowned Argyll car. Within a year of commencing production in 1906, the Argyll works in Alexandria were turning out more cars per year than any of their competitors outside of the United States – going on to introduce a range of models and to take several long distance and speed records, all of which added to the car’s prestige. Success was short-lived, for high overheads eventually forced the company into liquidation in 1914. With the outbreak of war in the same year, the Vale car factory immediately turned over to the production of munitions, with an enlarged but temporary workforce of nearly 3,000. As Britain began to rearm in the 1930s, the empty premises were taken over once more, this time for torpedo manufacture until 1969. The ship building yard of Dennys had flirted with aeroplane design from the earliest days of powered flight, including the development of an aircraft capable of vertical take-off which was flown for the first time in 1912. With war clouds gathering in Europe, the Blackburn Aircraft Company came to Dumbarton in the late 1930s, employing at its peak up to 4,000 workers. Several different types of aircraft were produced at the Blackburn factory, but the best remembered is the famous Sunderland Flying Boat. Some 250 that were built at Dumbarton went into service all over the world in the dual role of an anti-submarine and transport plane. Aircraft production in the town ceased soon after the end of the war.

Fig. 7.3 The famous Cutty Sark was just one of hundreds of ships built on the River Leven (Dumbarton Libraries collection).

Much less dependent today on just a few large companies providing employment for a substantial proportion of the local workforce, both Dumbarton and the Vale of Leven have overcome their disappearance by diversifying into a much wider range of light and service industries. Employment opportunities elsewhere on southern Loch Lomondside are very limited, and the villages in the Endrick and Blane Valleys are largely reliant on Greater Glasgow for work.

Water storage and supply

The water demands of an ever-growing population in central Scotland has meant that Loch Lomondside, with its high annual rainfall, has been at the very forefront of schemes for water storage and supply for both domestic and industrial use (Fig. 7.4).

Before 1855, when the Corporation of Glasgow finally decided on developing Loch Katrine in the Trossachs as a gravity feed water supply to the city, a number of other options had been under consideration. Amongst the schemes proposed was one to be sited in upper Strathendrick, which apart from a reservoir, would have included a conduit encircling the Campsie Hills via Strathblane and the Glazert Valley, intercepting many of the Campsie streams en route. Loch Lomondside was affected by Glasgow’s choice of Loch Katrine, however, first by its pipelines to the Milngavie holding reservoirs and later by the inclusion of Loch Arklet near Inversnaid into the scheme. In 1914 a dam was built across Glen Arklet’s western end, raising the surface height of a small existing loch by 6.7 m. Arklet Reservoir is connected to Loch Katrine by a tunnel through the Lomondside–Glen Gyle watershed.

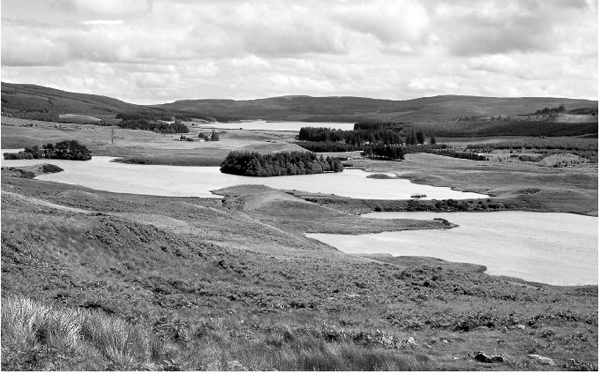

Water engineers had not lost sight of the upper Endrick Valley. The completion in 1939 of the Carron Reservoir was an unusual undertaking in that it straddled both sides of the Endrick–Carron watershed, requiring a dam at either end. When the valley was flooded, several farms with good quality agricultural land were submerged. In addition to east Stirlingshire, all of southeastern Loch Lomondside is now served by the Carron Reservoir, the fourth largest source of domestic and industrial water in Scotland.

Fig. 7.4 An early nineteenth-century cotton mill dam in the upper Endrick Valley is dwarfed by the twentieth-century Carron Reservoir in the distance.

Faced with a need for additional water supplies to the rapidly industrialising Vale of Leven, Renton extended a small lochan on Carman Muir, while the other townships turned to a Loch Lomond water pumping station near Balloch. In practice, pollution of the pumped water from the loch’s steamers and sewage discharge proved a constant problem, and the scheme was abandoned when a new reservoir in Glen Finlas in the Luss Hills became operational in 1909. The Finlas supply was later extended to Kilmaronock, covering all of the south side of the loch.

With both Dumbarton and neighbouring Clydebank having fully exploited the water gathering grounds of the southern Kilpatrick Hills, the last Clydebank reservoir to be built was sited some distance away from the town in the then untapped northern half of the hills. Opened in 1914, the Burncrooks Reservoir was constructed around one of the feeder streams to the River Endrick. About the same time as the Burncrooks scheme was being planned, Dumbarton Burgh was investigating the possibilities of enlarging Loch Sloy, some 32 km away in the Highlands. When this plan was turned down by a parliamentary commission of enquiry, the feasibility of reservoirs in Glen Luss and elsewhere was examined, but both cost and distance from the town became contributory factors in all the sites’ eventual rejection. Finally, spurred on by the summer drought of 1955 which left the town acutely short of water, Dumbarton turned to Loch Lomond. In June 1960, a small pumping station was opened on the lochside at Auchendennan, well away from the sources of pollution that had blighted the earlier pumping scheme at Balloch.

The Water (Scotland) Act 1967 brought into being the Central Scotland Water Development Board, whose remit was to initiate schemes to provide water in bulk throughout the densely populated and industrialised central belt of Scotland. Loch Lomond’s massive storage capacity made it a tempting choice. The Loch Lomond Water Scheme, which involved controlling the natural discharge from the loch by means of a barrage across the River Leven (Fig. 7.5), was officially opened on 29 June 1971. Through its pumping station at Ross Priory on the loch’s southern shore, the Board was given the authority to abstract up to 455 megalitres (100 million gallons) of water per day, providing the level of the loch does not fall below 6.7 m (22 ft) OD. To counter the loch’s falling water level in the driest summer months, additional storage capacity by the provision of supplementary reservoirs in Glen Fruin, Glen Luss and Glen Douglas was an option, but in the event not carried out. Anticipated rising water demand in the new millennium has necessitated further development of the Loch Lomond Water Scheme to increase the rate of abstraction.

Fig. 7.5 The barrage constructed across the River Leven at Dalvait ford has controlled the discharge of water from Loch Lomond since 1971.

The provision of hydro-electric power

Right up to the Second World War, the use of hydro-electric power in Scotland had been very low key. The Loch Sloy hydro-electric scheme on the west side of Loch Lomond, which was formally opened on 18 October 1950, was one of the great civil engineering achievements of the immediate post-war years, and the first of the newly formed North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s large-scale projects to be completed. By the construction of a dam linking Ben Vorlich with Ben Vane (Fig. 7.6) and increasing the loch’s natural water gathering ground by almost five times through a system of incoming aqueducts and tunnels from neighbouring catchments as far afield as Ben Lui, the water level of Loch Sloy was raised by a massive 47 m. From the reservoir, a 3.2 km tunnel was driven through the heart of Ben Vorlich to a 130 megawatt capacity generating station at Inveruglas overlooking Loch Lomond. Output was increased to 160 megawatts in 1999.

Fig. 7.6 The Loch Sloy hydro-electric scheme opened up former remote country.

Other projects have been proposed from time to time. Both conventional and pumped storage hydro-electric reservoirs on the headwaters of the Mar Burn above Balmaha were investigated, although neither of these schemes progressed further than the drawing board. The upgrading of Loch Sloy to pumped storage was also looked into, but the concept was eventually dropped. Finally, in 1976 the Hydro-Electric Board put forward their case for a pumped storage scheme at Craigrostan on the slopes of Ben Lomond, the upper reservoir sited on the headwaters of the Cailness Burn. As envisaged, it would initially have a capacity of 1,600 megawatts, but with the potential for upgrading to 3,200 megawatts. For reasons discussed in Chapter 13, the scheme was put in abeyance, and vastly increased costs in the future seem likely to prevent the project remaining a viable option in the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s successor’s long-term plan.

From everything outlined above, it can be seen that there is scarcely a valley or glen, river or standing water in the region that has not been drawn into or at least considered for one water utilisation scheme or another. From the very first small water bodies constructed to keep the water wheels of the local corn mills turning in summer to the regulating of Loch Lomond itself for urban and industrial needs over a wide area of central Scotland, the spread of dams and reservoirs, power and pumping stations, electric pylons and water pipelines has, within a comparatively short space of time, had an accumulative impact on the face of Loch Lomondside equal to that of much longer standing rural land uses.