8

Field Sports and other Recreational Activities

‘Loch Lomondside…I think this part of the Highlands is as wild

as any I have seen. We are upon the side of a great lake, bordered

round with exceedingly high mountains…A man in health might

find a good deal of entertainment in fair weather, provided he has

strength to climb up the mountains and has keenness to pursue the

game they produce.’

Correspondence of Lieutenant Colonel James Wolfe

(25 June 1753)

The transition from killing wild animals for essential protein to the ritualistic hunting of fur, feather and fin for the excitement of the chase was a gradual process. At Govan Parish Church further upstream on the River Clyde, there is a sarcophagus with a carved depiction of red deer and wild boar closely pursued by a mounted nobleman, possibly representing one of the kings of Strathclyde. The sarcophagus appears to be of late ninth-century design, although similar scenes on earlier Pictish symbol stones elsewhere in Scotland suggest that participation in the hunt just for pleasure was commonplace before then. Such field sports evolved from the need to control wild beasts of the forest which posed a threat to livestock and crops, but hunting dangerous animals from horseback was further encouraged in gaining skills with weapons of war.

The hunting grounds of Robert the Bruce

The earliest documentary source on the royal passion for the hunt are the Scottish Exchequer Rolls, which show that in his latter years between 1326 and 1329 Robert I created an 80 ha palisaded deer park and falconry mews beside his manor house on the west bank of the River Leven, believed to be the same place now known as Mains of Cardross at Dalmoak. Outside the enclosed park lay the king’s hunting preserve on the edge of the Highlands, where the fourteenth-century chronicler John Fordum tells us: ‘along the foot of these mountains are vast woods, full of stags, roe-deer and other wild animals and beasts of various kinds’. With most of the hunt servants on foot, unleashed dogs were used to chase and hold the quarry at bay until the king’s party caught up. The pack kept by Bruce are said to have been large white hounds first brought over from France at the time of the Norman Conquest.

According to the historian Boethius, on one of King Robert’s hunting expeditions he narrowly escaped with his life when a wild white bull (Bos taurus) turned on his pursuers, such a moment vividly captured by Sir Walter Scott:

‘Mightiest of all the beasts of chase,

That roam in woody Caledon,

Crashing the forest in his race,

The Mountain Bull comes thundering on’.

As the forest cover receded, the last of these ancient white cattle were herded into parks at Cumbernauld (East Dunbartonshire) and Stirling, where the fierceness for which they were renown was gradually bred out. Their descendants, with their distinctive black ears and muzzles (Fig. 8.1), can still be seen at Chatelherault, a former hunting lodge of the Dukes of Hamilton in Lanarkshire and at Cumbernauld’s Palacerigg Country Park.

Deer parks

Robert the Bruce was probably the first to introduce fallow deer to Loch Lomondside, this favourite beast of the chase of the Norman–Scottish nobility having been kept in the Kings Park at Stirling since at least 1290. After Levenside, the next deer park to be created in the area was on Inchmurrin, the old castle at the west end of the island serving as a hunting lodge for the lairds of Lennox and their royal guests. Again, the species of deer introduced is not mentioned in the earlier records, and it is left to the sixteenth-century map maker Timothy Pont to note: ‘in this yle ar many fallow deer, whair the kings used hunting sumtyme’. In 1663 the Colquhouns laid waste to Inchlonaig for the sole use of fallow deer. Between them, the two island deer parks supported some 450 head of fallow, a high stocking rate that could only be sustained during the lean months of winter by supplementary feeding. The last fallow deer herd to be established on Loch Lomondside was in the Colquhoun’s pleasure grounds of Rossdhu House in the mid-nineteenth century. On Inchlonaig and in the deer park at Rossdhu, metal tree guards were placed around many of the trees to prevent damage to them by the deer. As management of these herds declined, the park-bred fallow deer began to escape from their confinement and establish themselves in the wild.

Fig. 8.1 Descendants of an ancient breed of white cattle that once roamed wild in Scotland’s forests.

Deer forests

In the social upheaval that followed the Jacobite uprising of 1745–46, red deer numbers in Scotland were reduced to an extremely low ebb by indiscriminate killing, so much so that on Loch Lomondside the incoming blackface sheep initially had the uplands to themselves. The first sign of a change in the fortunes of the red deer came with the creation of deer ‘forests’ – more often than not, just open hill ground – entirely for sporting purposes. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, wandering animals from newly established deer forests at Blackmount and Glen Artney (both outwith the Loch Lomond area) did occasionally put in an appearance, but because of their potential for damaging the oak coppice woodlands still in full production, the deer were not encouraged to settle.

Attitudes changed dramatically from about 1880, when the rental value of the hill sheep grazings plummeted to an uneconomic level, as large-scale imports of colonial wool and mutton undermined market prices. Yet at the same time the demand for sporting lets in Scotland had never been higher, spurred on not only by a significant reduction in travelling time from England with the coming of the railway, but the sovereign seal of approval bestowed upon deer stalking in the Highlands by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Balmoral. In line with this new sporting fashion, a number of sheep walks on Loch Lomondside were converted to deer forest. These included Glen Falloch, Loch Sloy (Ben Vorlich and Ben Vane), Inversnaid and Rowardennan (Ben Lomond) forests. Hunting lodges – some in the pseudo-baronial style (Fig. 8.2) – were specially built to accommodate the proprietor’s guests and sporting tenants, together with their retinue of domestic staff. Shot beasts were brought down off the hill by sure-footed Highland ponies, a task entirely taken over today by all-terrain vehicles. Overall, the quality of the stags killed on Loch Lomondside has not been exceptional, although included among the trophy heads have been several much coveted 12 pointers or ‘royals’.

Fig. 8.2 A former purpose-built hunting lodge at Rowardennan is now a popular youth hostel.

This peak in the management of several Loch Lomondside estates for red deer was cut short by the outbreak of the First World War. Prices for home-produced wool and mutton rapidly recovered and all able-bodied sportsmen and professional deer stalkers found themselves fully occupied with the British expeditionary forces abroad. Subsequent organised stalking in the district has been far less intensive which, together with the extensive cover provided by recent afforestation of the hills, has led to a marked increase in the Lomondside red deer population – currently estimated at between 1,500 and 2,000 animals – their range extending southwards well below the Highland Line.

Grouse moors and pheasant coverts

When the only available firearm was the heavy, muzzle-loading flintlock, the hunting of red grouse and pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) – the latter introduced locally as a sporting bird in the early nineteenth century – could be a very arduous affair. Walking the woods and moors with dogs trained for pointing or flushing out the concealed game usually meant a long, tiring day for only a modest return. The sport was transformed by the development of the breech-loaded waterproof cartridge, with its speed in reloading and ability to perform in all weathers. This led in turn to the emergence of the sporting estate. Shoots became organised with military precision, the grouse or pheasants driven by a line of beaters towards the waiting guns, enabling for the first time huge numbers of birds to be killed. Every estate owner competed with his neighbours to produce the largest head of game for the season for, apart from social prestige, where the shoot was let, the greater the number of birds shot the higher the sporting rent which could be asked the following year. Records kept for the Buchanan grouse moors show that the most productive period occurred just before the First World War, the number of grouse shot peaking at over 1,800 birds in the 1911 season, 480 on 6 September alone. The best season for pheasants in the Buchanan coverts and coppice woodlands was the winter of 1909–10, with nearly 2,000 birds killed, a single day’s shooting on 16 November accounting for almost half of the total bag.

The presenting of such artificially high numbers of grouse and pheasants to the waiting guns had only been achieved by the almost total elimination of all predatory mammals and birds by gamekeepers engaged for this purpose. Some proprietors initiated a bounty system, a specified payment made for each carnivore or bird of prey destroyed. Recalling the former abundance of natural predators on the Luss Estate before their ruthless slaughter began, the mid-nineteenth-century sportsman/naturalist John Colquhoun wrote:

‘ The golden eagle built in Luss Glen, so did several pairs of peregrines in the wilder cliffs. I have myself seen, in one season, three nests of that sylvan ornament the kite – one in an oak tree on Rossdhu lawn, and the other two in the pine wood of an adjacent mountain. The marten was constantly flushed in the same pine wood, nay, even in the lower grounds; and the wildcat was far from rare. In the course of time my brother engaged a first-rate lowland gamekeeper, whose trapping feats on the carnivora were even more exciting than anything the game could show; and the rarer, wilder, predatory birds and beasts rapidly disappeared.’

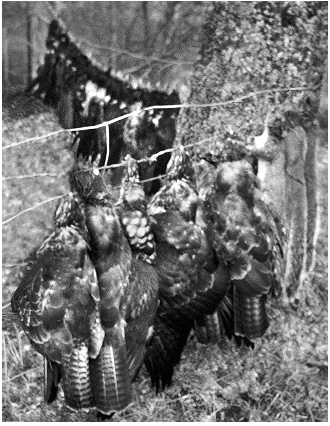

Displaying the grisly corpses of these animals on a gibbet (Fig. 8.3) was widely practised by gamekeepers, for it showed to their employers that they were conscientiously carrying out their appointed task. The following contemporary description of one such gibbet on a Loch Lomondside estate exemplifies the single-minded onslaught against all known and suspected predators of game:

‘Vermin of all kinds and degrees are here treated with well-merited rigour. The toad that plunders the hen-roost, the sleeky weasel, and the stoat – egg suckers by habit and repute from time immemorial – with the hoodie-craw, the hawk and the owl – all birds of evil omen to the game – are here sacrificed with the shortest possible shrift. Look at these relics of departed reivers (thieves) nailed on the rafters of the kennel, and think what a salvation of innocent partridges and grouse has been effected by their destruction.’

The predators of game fish were similarly dispatched, Colquhoun going on to describe how otters (Lutra lutra) were trapped on the loch. Goosanders (Mergus merganser) and red-breasted mergansers (M. serrator) were shot on sight as a matter of course, but the Montrose Estate gamekeepers did at least spare the breeding colony of grey herons on the lower reaches of the Endrick on account that ‘herons’ formed part of the Montrose family’s coat of arms. In John Colquhoun’s own words, the fish-eating ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) nesting on Inchgalbraith, part of Luss Estate, were destroyed during a ‘vermin crusade’. The rarer creatures killed in the interests of game preservation were sent to taxidermists’ establishments in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Perth, the Victorians’ passion for stuffed birds and mammals in the parlour or trophy room placing an additional price on these animals’ heads.

The impact of this wanton persecution by gun, trap and snare was such that a number of native animals, notably the pine marten (Martes martes), polecat (Putorius putorious), wildcat (Felis catus), red kite (Milvus milvus), hen harrier (Circus cyaneus) and osprey were totally banished from the area. Well over a century later, the polecat and red kite have yet to re-establish themselves, and even the others are still very scarce. Apart from the local extinction of several species of predator, another unfortunate legacy of the game bird culture during the Victorian and Edwardian periods was the widespread planting of rhododendron as cover for the pheasants. Now thoroughly naturalised, this all too successful shrub has invaded many of the Loch Lomondside woodlands, its dense evergreen foliage totally shading out the native ground flora and preventing regeneration of indigenous trees. To date, all attempts to bring rhododendron under control have all been on a small scale and consequently had little overall effect.

Fig. 8.3 A row of illegally killed buzzards on a modern day gamekeeper’s gibbet (Robert Pollock).

After the First World War, the returning sportsmen and gamekeepers picked up where they had left off. For red grouse, 1934 with its fine summer weather was a particularly good year on most of the local estates, the Buchanan moors yielding 1,800 birds in nine days of driving. As the acreage of good heather moor receded from a gradual run down in moorland management, overgrazing by sheep, bracken infestation and the advent of upland afforestation, red grouse numbers on Loch Lomondside went into a steep decline. On formerly well-stocked moors where the seasonal bag of grouse was once counted in hundreds, hardly a bird can now be seen. Pheasant shooting, on the other hand, has generally held its ground, although it is maintained only through the buy-ing-in and releasing of large numbers of hand-reared birds each autumn to supplement the small breeding stock. Attempts have been made to introduce the red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa) from time to time, but this predominantly southern European species appears unable to acclimatise to the region’s cool and wet climate. Even the North American wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) was tried out in Rossdhu Park for a while.

Wildfowling and snipe shooting

Most of the wildfowling on Loch Lomondside is concentrated in and around the Endrick Marshes, where the largest number of birds feed and roost. Estate game books covering the late nineteenth– early twentieth centuries show that duck were a favourite quarry, but the almost complete absence of goose entries confirms that today’s high numbers of wintering geese in the area is a fairly recent phenomenon. The winter-flooded Wards Low Ground is a legacy of the heyday of wildfowling on the Endrick Marshes, with the abandonment of badly drained arable ground in favour of flighting ponds to attract wild duck towards the concealed guns.

Marsh hay meadows after cutting in late summer gave the opportunity of large bags of common snipe (Gallinago gallinago). In the 1873–74 season, one of the landed proprietors of the Endrick Marshes – Sir George H. Leith Buchanan – shot a record total of 350 snipe on his ground.

Angling

A dedicated angler has by nature to be an unshakeable optimist. The Loch Lomond fisherman’s lament says it all – ‘washed off by rain, blown off by wind, driven off by despair’ – yet still he returns time after time to try his luck once more in a favourite drift.

Much is owed to visiting anglers for our knowledge of the early development of sport fishing on Loch Lomond and its tributary rivers. To be expected considering the unsettled times, all concerned were military men. The first was Richard Franck, a lieutenant quartermaster in the Cromwellian army during the Civil War. It was a second tour of duty to a more peaceful Scotland in 1658 which gave Franck and his travelling companion the opportunity of casting their rods over the River Leven. Catching both salmon and sea trout, it was the first locally recorded instance of use of an artificial fly. Lieutenant Colonel James Wolfe (later in life to become a national hero as General Wolfe of Quebec) must have noted the angling potential of the area while temporarily stationed at Inversnaid garrison after the Battle of Culloden, for he made sure to bring along his fly-fishing rods when posted again to Loch Lomondside with five companies of soldiers from the 20th Regiment for military road building in the summer of 1753. The account of Colonel Thomas Thornton’s highly successful sporting tour of Scotland undertaken ca. 1786 is especially instructive, particularly for the wealth of detail on eighteenth-century angling techniques and tackle.

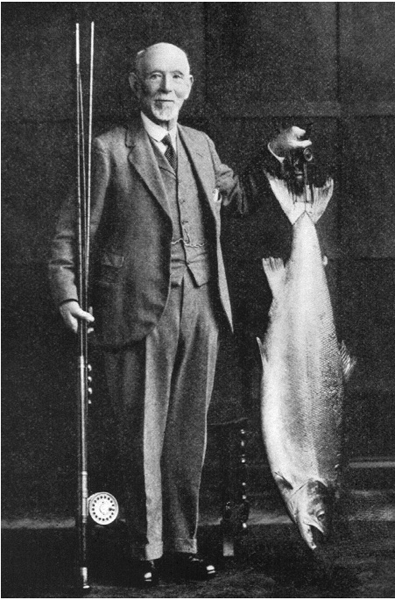

Then as now, the special attraction of Loch Lomond was the chance of landing a large specimen fish. Thomas Thornton’s record fish was a 7 lb 7 oz (3.3 kg) perch (Perca fluviatilis), which he carefully weighed on his portable scales. Even today, this weight remains unchallenged for a Scottish rod-caught perch. And again, a 41 lb (18.6 kg) Atlantic salmon taken from the loch by Thornton was not beaten for 126 years, when a remarkably good fish was successfully played by Mr Edward Cochran on 15 April 1930. Weighing in at 44 lb (20 kg), this once-in-a-lifetime salmon (Fig. 8.4) is a record for Loch Lomond yet to be surpassed. In more recent years a 22 lb 7 oz (10.2 kg) sea trout, caught in the River Leven on 22 July 1989, became the new British record for the species.

If a really gigantic fish is going to be taken from the loch, it will undoubtedly be the predatory pike (Esox lucius), a fully-grown specimen capable of putting up a fight to test the mettle of even the most seasoned angler. Loch Lomond abounds with enormous-pike-that-got-away stories, but one that did not in July 1947 was found to weigh 47 lb 11 oz (21.6 kg). This British rod-caught record was by no means the first big pike to be encountered locally, for a massive specimen was found marooned in a lagoon near the Endrick Mouth ca.1934, its weight estimated at 50 lb (22.7 kg) or more. The creature’s fear-somelooking head is preserved in Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Museum. Based on stories of monster pike from the early days of angling, the distinguished nineteenth-century zoologist William Yarrell was convinced that the productive waters of Loch Lomond were capable of producing a colossus well in excess of 70 lb (32 kg). He might yet be proved right.

Fig. 8.4 Mr Edward Cochran with his record-breaking salmon from Loch Lomond (Author’s collection).

Regrettably, some visiting anglers have not been content with pitting their piscatorial skills against Loch Lomond’s indigenous fish, irresponsibly introducing a number of southern species (see Chapter 9) with the potential for unstabilising the loch’s ecological balance evolved over thousands of years. The deleterious effects of industrial effluent discharged into the Rivers Leven and Blane has already been mentioned. It was this together with over-netting of migrating salmonids moving up river to their traditional spawning grounds which led to the setting up of an organised body in the mid-nineteenth century to combat these particular problems. After overcoming several setbacks, the Loch Lomond Angling Improvement Association in its present form was established in 1901. With a large membership, the LLAIA employs full-time water bailiffs and maintains its own salmon and sea trout hatchery for restocking purposes.

Mountaineering and rambling

Of all Loch Lomondside’s outdoor recreational pursuits, ‘mountaineering’ attracts the largest number of devotees. Most would modestly describe themselves as hill walkers, but there is a small hard core of rock and ice climbers, together with downhill skiers in winters with sufficient snow.

In the early days of travel, the Scottish mountains were regarded by visitors from the south as both desolate and frightening, places to go out of one’s way to avoid. A gradual change in perception can be seen in the journal of the literary figure Thomas Gray, who, during his first visit to Scotland in 1764, enthused over the mountain landscape around Loch Lomond which he thought exquisite. But if the followers of the ‘picturesque’ movement who came hard on his heels found the serenity of mountains reflected in the still surface of the loch an uplifting spiritual experience, most still detested the sight of peatbog and moor. As one early guide book to the area described the Muirpark route between Drymen and Gartmore: ‘nothing can be bleaker than the scene which presents itself at the summit of the hill’.

Shepherds and fox-hunters regularly crisscrossed the region’s hills in the course of their duties, but actually going up a mountain just for the pleasure of standing on its summit to take in the view was unheard of until the mid-eighteenth century. Loch Lomondside’s first recorded touristic ascent took place in the year of 1756, when a Cambridge University graduate William Burrell and several of his friends set their caps at scaling Ben Lomond. According to his diary, Burrell was overcome with vertigo on the final approach to the top and had to descend, but his unheeding companions forged ahead to ‘feast very heartily’ on the summit. Initially only an intrepid few followed their example, but by 1804 James Denholm in his Tour to the Principal Scotch and English Lakes observed that ‘the greatest part of travellers who visit Loch Lomond upon a pleasure excursion take advantage of the ferry at Inveruglas [Inverbeg], and cross the lake to ascend Ben Lomond’. Colonel Peter Hawker, who is credited with the first winter ice climb on the Ben, added that in summer ‘ladies very commonly go up, and sometimes take with them a piper and other apparatus for dancing’. A new breed of professional mountain guide emerged, with horses for hire to carry the less energetic to the summit. Visitor numbers to Loch Lomond did temporarily fall away with the appearance in 1810 of Sir Walter Scott’s poetical work Lady of the Lake, which drew the tourists clutching their copies of the book more towards Loch Katrine, but the popularity of Loch Lomondside fully recovered seven years later after Scott published his locally set novel Rob Roy.

What began as a gentleman’s leisure pursuit, to be followed in turn by the professional classes, gradually encompassed a wide range of Scotland’s social spectrum as Saturday afternoons off from work became commonplace and the rigid Sabbath observance customs were relaxed. As the second half of the nineteenth century progressed, the improved rail and steamer services allowed the new excursionists – who were intent on cramming as much as possible into a one day trip – to reach Loch Lomond in ever increasing numbers. Railway engineers from Snowdonia in North Wales even investigated the possibility of a mountain railway to the top of Ben Lomond, but the idea came to nothing. The Campsies too proved extremely popular. Hugh MacDonald’s Rambles Round Glasgow (1854), which included described walks over Loch Lomondside’s southern foothills, went through several editions to meet the new demand. By the early 1890s, at least ten different rambling clubs were operating out of Glasgow alone.

Others in the pursuit of some scientific enquiry or other were afoot in the Loch Lomondside hills right from the beginning. The Reverend John Lightfoot and George Don are just two from a long list of distinguished botanists whose early explorations of the high tops contributed to our knowledge of the region’s montane flora. Amongst a rash of natural history bodies founded in the mid-nineteenth century was the Perthshire Mountain Club, which, in the Loch Lomond area, directed its attention to the Glen Falloch Hills. Eligibility to the club was restricted to those members of the Perthshire Society of Natural Science who could claim to have botanised in the county at altitudes of over 3,000 ft (914 m).

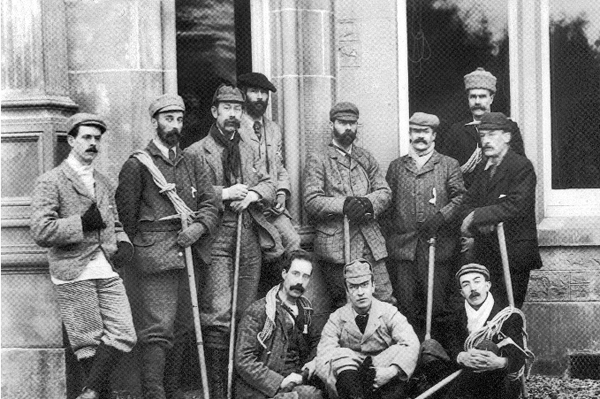

The very first mountaineering organisation in Scotland was formed in 1866 at Glasgow’s Old College – the forerunner of the present University. Known as the Cobbler Club, after the Arrochar area’s best known summit, its stated aim was to promote the climbing of every worthy hill that could be reached from Glasgow in the course of a Saturday excursion; and ‘to crown the labours of the day by such an evening of social enjoyment as can only be spent by those who have had a sniff of true mountain air’. From these early beginnings came the Scottish Mountaineering Club (Fig. 8.5), formally constituted in Glasgow on 11 March 1889, publishing the first issue of the club journal in January of the following year. From the very start, the SMC’s journal enthusiastically pointed the way to rock outcrops near to hand such as the Whangie in the Kilpatrick Hills, still a popular climbing spot. Newly described routes on the higher rock faces of the southern Highlands came thick and fast and there is even an account of a 600 ft (185 m) winter snow glissade made down Ben Lomond’s northeast corrie. A milestone in Volume I of the journal was the publication of Sir Hugh Munro’s ‘Tables giving all the Scottish Mountains exceeding 3,000 ft in height’. A total of 538 tops of 3,000 ft (914 m) or over were listed, including 283 given the status of separate mountains. The latter almost immediately became known as ‘Munros’, and reaching the summits of them all presented a challenge to many club members. There had been the occasional peak collector before, such as the geologist John MacCulloch in the early part of the century, but now ‘peak-bagging’ as a sport was pursued in earnest. The first person to complete an ascent of all the listed Munros and subsidiary tops was the Reverend A.R.G. Burn, realising his objective on 20 July 1923 having saved the twin-topped Beinn a’ Chroin at the head of Glen Falloch for his celebratory final one. Although peak-collecting aimed at making a high personal score was initially frowned upon by the club elders, hundreds of dedicated Munroists have followed the Reverend Burn’s example.

Fig. 8.5 A Scottish Mountaineering Club meet at Tarbet in 1895 (S.M.C. collection).

It was one of the founder members of the Scottish Mountaineering Club, W.W. Naismith, who first introduced Norwegian skis into the country, giving them a trial run on the snow-covered Campsie Hills in March 1892. Despite coming to grief several times, Naismith concluded his assessment of the future of skiing in Scotland with what proved to be a prophetic statement: ‘it is not unlikely that the sport may eventually become popular’. Ice skating on the loch is the one winter sport that has dramatically declined. Prolonged periods of intense frost producing weight-bearing ice have become so infrequent that the once familiar spectacle of hundreds of skaters besporting themselves on the loch’s frozen surface is no longer within living memory.

Numbers participating in hill walking continued at a high level throughout the latter years of the nineteenth century and up to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This period was to witness serious clashes between ramblers who wished to exercise their much cherished freedom to walk unhindered over open countryside, and landowners attempting to impose exclusivity over Loch Lomondside’s newly created deer forests and grouse moors by closing paths and tracks used from time immemorial. As W. C. Paterson commented on the land closures in his collection of poems Echoes of Endrickvale, published in 1902:

‘They’re kept for deer an’ whirrin’ grouse,

By rich sportsmen executed,

So sacred is the shrine of sport,

Trespassers Prosecuted.’

When James Bryce MP secured a debate on his Access to Mountains (Scotland) bill, which was brought before Parliament but without success in March 1892, he specifically referred to the extreme measures taken by the sporting proprietors of the Kilpatrick Hills. Prevented from setting foot on these hills by prohibitive signs, barbed wire, threat of litigation and even physical violence, the people of Dumbarton finally became so incensed that in May 1911 a mass demonstration took place on the Overtoun Estate, where a locked gate across the road was torn from its hinges. Demonstrations against path closures also took place in Balloch, after walkers found the southern shores of Loch Lomond closed to them. Despite the outcry, the public only fully regained their traditional right of access to Loch Lomond when Balloch Castle and its grounds were purchased by the Corporation of Glasgow in 1915.

After the inevitable lapse of support for organised outdoor pursuits during the First World War, a resurgence of interest led to the formation of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Ramblers Federation, who, by chartering trains and steamers, could assemble parties of up to 500 members at Rowardennan to walk en masse up Ben Lomond. Glasgow again led the way with the Rucksack Club of Scotland, pioneering the providing of hut accommodation for the use of its members. The Rucksack Club gave way in turn to the Scottish Youth Hostel Association, and Inverbeg was chosen in 1931 for the organisation’s first hostel on Loch Lomondside. When the SYHA formally opened Auchendennan House near Balloch on 6 April 1946, it was claimed to be the largest outdoor activities centre in the world.

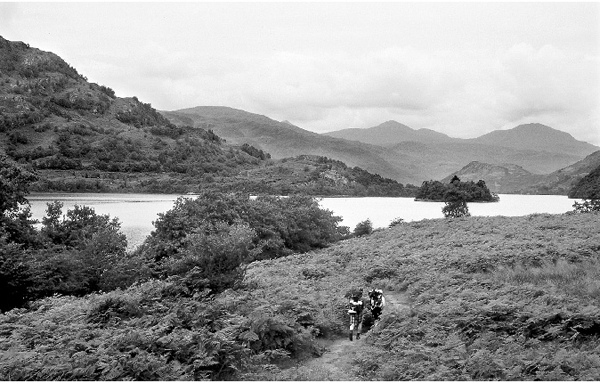

As found elsewhere, such as in the Lake District of England, the over popularity of certain parts of Loch Lomondside with those seeking the outdoor experience has left its mark. Clearly seen from miles away, the disfiguring linear scar leading up the southern shoulder of Ben Lomond bears witness to the cumulative effect of countless trampling boots. On its severely eroded summit, the botanist will look in vain for the covering of moss heath with its cushions of pink-flowered moss campion (Silene acaulis) that so delighted the early visitors to the top. Even on the low ground, some sections of a once secluded and little used woodland path on the east side of the loch become churned into quagmires in wet weather since it was linked into the West Highland Way (Fig. 8.6), a well-publicised long distance walkers’ route from Milngavie to Fort William that is completed by over 50,000 participants each year.

Powerboating

No outdoor recreational pursuit on Loch Lomondside has altered more in character than boating. Although sedate pleasure cruising, yachting and canoeing on the loch still attract their devotees, others are drawn by the excitement of fast water sports such as water-skiing, jet-skiing and the like. This change in emphasis was made possible by massive upgrading in engine size and power, compared to the older outboard motors that were capable of achieving only a few knots per hour. Fast water sports exercise a hugely disproportionate intrusion on the tranquillity of the loch for the comparatively small number of participants involved. Quite apart from assailing the ears of those who come to Loch Lomond for the quiet contemplation of the magnificent lakeland scenery, or frustrating the salmon angler as he sees the waters around favoured fishing banks repeatedly churned over, the recent influx of speedboat, water- and jet-ski enthusiasts give little respite to the loch’s summer wildfowl with their young broods which depend on sheltered and undisturbed feeding waters to survive. In these same shallow waters, the underwater aquatic plant growth and its dependent invertebrate fauna can be badly affected by both propeller damage and increased turbidity from the stirring-up of the loch bed. In addition, ever-increasing levels of toxic residues from engine fuel are being detected at peak periods in the most frequented areas. Well in excess of 5,000 power craft are registered for use on Loch Lomond, a recent census figure showing that over 1,000 can be out and about on fine summer days.

Hand in hand with the expansion in powerboat usage on the loch has been an upsurge in the number of day-trippers to the islands, especially to those with attractive beaches. Inchmoan with its long stretches of fine sandy shores was once noted for the birds nesting at its water’s edge, but these have all but disappeared in the face of increased recreational pressure.