12

Muirs and Mountains

‘The hill lands are one of Scotland’s most precious features…from all

over the world visitors come to see their magnificent scenery. The

wildlife is an important part of this richness. Imagine how bleak our

hills would be if no golden eagles swept over the ridges, no arcticalpine

flowers shone like jewels on the dark rocks, and no heather

bloomed on the moors.’

‘Wildlife on the Hill’ (Adam Watson) in

Wildlife of Scotland (Holliday, 1979)

Completing Loch Lomondside’s outstanding diversity of wildlife habitats is the high country above the old head dykes. It is unfortunate that when comparisons are made with Scotland’s most imposing massifs, such as Ben Nevis, the Cairngorms and the Torridon range, the Lomondside hills and mountains hardly ever receive their just recognition. Yet they have their own individual appeal. This lies not only in the variety of topographical features, but in their ready accessibility to Scotland’s largest urban population.

Muir burning coupled with sheep grazing have together brought about dramatic changes to the vegetation cover of the Loch Lomondside uplands in the last 250 years. Fire as a management tool has been used by stock graziers since Neolithic times. Carried out in a judicious manner, burning is an effective method of removing old plant growth to make way for a flush of palatable young shoots, the soil becoming temporarily richer in minerals absorbed from the ashes of the fire. But from the middle of the eighteenth century, when the practice was followed by a high stocking density of sheep selectively feeding on the new growth, loss of heather was inevitable. As one agricultural writer of the period observed: ‘Where the heath has been burned, there is always a powerful growth of grass…the heath has by degrees disappeared, and the dusky mountains become covered with a lively verdure’. This apparent satisfaction at the change in appearance of the uplands was ill-founded, for on the rain-sodden and mineral-depleted soils of the west of Scotland the ling heather and other heathland plants were being replaced by nutritionally poorer species such as mat-grass (Nardus stricta), purple moor-grass, deergrass (Trichophorum cespitosum), common cottongrass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and heath rush (Juncus squarrosus). Bracken too was gaining a competitive advantage from the practice of over-firing the heather, the dormant rhizomes of this aggressive fern safely under the ground when the spring burning was carried out. As the quality of the pasture gradually declined, the high numbers of sheep could no longer be sustained, with the result that in recent years, large areas of the upland grazings have been sold off for conifer afforestation.

For the purposes of this chapter, the Lomondside uplands have been divided into four geographical areas: the southern foothills, the Luss Hills bordering the Highland Line, the northern plateaux and finally the mountains with their high-level crags and sub-arctic summits.

Fig. 12.1 The Campsie Hills or Fells, the alternative name derived from the old Norse word fjell.

The southern foothills

Dissected by the movement of past glaciers, the southern foothills comprise three sections of the Clyde Lava Plateau – the Kilpatrick, Campsie (Fig. 12.1) and Fintry Hills. Each of the plateau’s three distinct blocks differ in their main habitat types; the Campsie Hills’ high-level blanket bogs and northern corries, the Fintry Hills’ south facing and, in places, calcareous basaltic crags, the Kilpatrick Hills’ reservoirs, extensive conifer plantations and remaining sweeps of heather moor, which descend to relatively low levels on the hills’ northwestern edge.

The most elevated land of the lava plateau is covered by blanket bog, a thick layer of compacted and partly decomposed plant remains that has developed directly on top of the waterlogged mineral soils. Like all of the Loch Lomondside uplands, the foothills have been subject to intensive sheep grazing and regular heath burning over a long period, and much of the former ling heather cover has been replaced by common bent (Agrostis tenuis), sheep’s fescue (Festuca ovina) and mat-grass dominated grasslands. With their close proximity to the Clyde conurbation, the southern foothills also have a history of being affected by atmospheric pollution since the beginning of the coal and coke-fired Industrial Revolution. As far back as the 1870s, Glasgow cryptogamists had become aware that something was seriously amiss, recording that there was scarcely any species of lichen to be found in a state of fructification within a 10 mile (16 km) radius of the city. Few observations on deleterious changes to other plants of the city’s surrounding countryside appear to have been made, but moorland species such as the round-leaved sundew, bog-myrtle, woolly fringe moss (Rhacomitrium lanuginosum) and, most importantly, the peat-forming bog mosses, have been shown in other parts of industrialised Britain to retreat in the face of soot-laden emissions from mill, factory and town. Providing the level of pollution is not too high, however, a few upland plants such as cottongrass and blaeberry show no visible sign of deterioration; in fact with reduced competition they may even spread over a much wider area.

With low cohesion within the accumulated peat, all blanket bogs are inherently unstable and susceptible to natural erosion by the weather elements. It is believed, however, that on Loch Lomondside’s southern foothills the pace of this degenerative process has quickened over the last two hundred or so years, the result of poor growth in the peat-forming sphagnum mosses. Apart from atmospheric pollution, excessive muir burning can destroy the living top layer of water-retentive sphagnum moss. Moor-gripping (the cutting of open drains in the peat) is also implicated, accelerating the fragmentation of the bog surface. Hart Hill (522 m) in the Campsies is the least degraded example of blanket bog, but even here the surface has broken up into a network of peat haggs bisected by deep gullies. Despite this deterioration, just to see the carpeting of cloudberry (Plate 12) and cowberry is well worth the climb. Up to the mid-1980s, a strong presence of golden plover (Pluvialis apricaria) was another of Hart Hill’s attractions. Some of the birds were ‘northern’ in type, in that the black markings on the face continued in a narrow but unbroken strip to the black underparts. There was even an accompanying pair or two of dunlin, sometimes referred to as the ‘plover’s page’. Regrettably, the current depleted numbers of upland waders holding territory on Hart Hill in spring is a story repeated throughout the southern foothills. With a marked reduction in pest control, unchecked increases in both fox and carrion crow (Corvus corone) numbers have undoubtedly played their parts in the decline. The few breeding pairs of hen harriers present on the southern foothills are not confined to heather moor or young forestry – the most common habitats for the species – but will readily nest in a bed of rushes, a fact first noted over 200 years ago by one of the local parish ministers.

Remains of old shooting butts, where sportsmen awaited the driven red grouse, point to this game bird’s former importance in the area. Red grouse are unique to Britain, and as such have attracted sportsmen from all over the world to pit their shooting skills against these fast-flying birds. The numbers of grouse go through cyclic fluctuations on these rather wet heather moors. In the autumn of 1988 – following one of the best breeding seasons in recent years – a quite exceptional assemblage by today’s standards of over 250 red grouse gathered on Hart Hill for the berry crop. Another species present that is subject to rises and falls in abundance is the blue hare. Curiously, none of the early naturalists’ accounts of Loch Lomondside’s mammal fauna make any mention of the blue hare below the Highland Line, which would seem to suggest that the isolated population on the southern foothills originates from sporting introductions by the nineteenth-century proprietors of the moors. The animal’s numbers were at an exceptionally high peak when the Forestry Commission established a 464 ha plantation on the northern Kilpatrick Hills in 1967. In order to protect the seedling trees, several hundred blue hares were shot within the enclosure in the two years following the completion of the encircling fence.

The successive layers of basaltic lavas exposed along the northern and western edges of the Campsie hills vary considerably in their mineral content and in consequence both calcicole and calcifuge plants can often be found growing in close proximity. One moderately rich basalt outcropping at Black Spout, a minor waterfall near the base of the north-facing scarp, is festooned with mossy saxifrage (Saxifraga hypnoides), wood crane’s-bill (Geranium sylvaticum) and red campion (Plate 13), with sheets of opposite-leaved golden saxifrage where water continually trickles down the rock. Higher up the northern face, the vegetation becomes distinctly more montane in the twin Corries of Balglass, both carved out by small corrie glaciers at the time of the Loch Lomond Stadial glaciation. In addition to the basalts, a high-level exposure of Ballagan Cementstones in the Little Corrie of Balglass adds to the beneficial effect of mineral flushing on the flora. Upland species represented in the two corries include roseroot (Sedum rosea), pink stonecrop (S. villosum), northern bedstraw (Galium boreale), chickweed willowherb (Epilobium alsinifolium), yellow mountain saxifrage (Saxifraga aizoides) and fine tufts of the silky red moss Orthothecium rufescens. More typical of the acidic outcrops, parsley fern (Cryptogramma crispa) maintains a precarious footing in the unstable screes of loose stones below the frost-shattered cliffs. Even though the Campsies reach 578 m in height, these hills lack a surprising number of the commoner mountain flowers of Scotland, such as alpine lady’s mantle, which is both widespread and abundant in the Highlands just to the north. The covering of forest on these hills during the climatic optimum could explain these flowers’ local extinction, the Clyde Lava Plateau’s isolated position ensuring that few montane species would recolonise after the tree cover disappeared.

Contrasting with the shady and usually damp northern corries of the Campsies are the dry, south-facing cliffs of the Fintry Hills on the other side of the Endrick Valley. One of these outcrops – Double Craigs (Fig. 12.2) – supports a very localised assemblage of calcicole plants, including limestone bed-straw (Galium sterneri), spring cinquefoil (Potentilla neumanniana), vernal sandwort (Minuartia verna), kidney vetch (Anthyllis vulneraria) and common rock-rose (Helianthemum nummularium). Exposed to most of the available sunlight, these basalt crags are particularly rich in saxicolous (rock-growing) lichens. The drought-resistant grasses squirrel-tail fescue (Vulpia bromoides) and yellow oat-grass (Trisetum flavescens), which are present in the dry grassland below the Double Craigs, are an indication of the much lower average annual rainfall experienced in the extreme southeastern portion of an otherwise very wet region. Jumbles of fallen rocks below the cliffs offer a retreat for the hill fox; and despite the strenuous efforts of the foxcatchers every cubbing season, the local population continues to hold its own. One dog fox killed near Fintry in January 1998 was found to weigh 12.25 kg (27lb), a remarkable size for the species by any standard. Todholes and Balgair are two settlements in the Fintry area named after the fox.

Upland birds are generally well represented on the Clyde Plateau’s terraced scarps or amongst the boulders and screes below; peregrine (see p. 192), kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), common buzzard, raven, ring ouzel (Turdus torquatus), wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe) and twite (Carduelis flavirostris) all finding a nesting niche. Observations have shown that the kestrel population rises and falls with the periodic fluctuations in the numbers of short-tailed voles in the hill grazings. In years of high vole activity, up to three pairs of kestrels have been found nesting on a single cliff. Buzzards soar effortlessly on the scarp’s updraughts, their keen eyes watching for the slightest movement betraying the presence of rabbits, or the corpse of an unfortunate sheep that had strayed too near the cliff edge. The ravens on the Kilpatrick–Campsie–Fintry Hills have been much persecuted since intensive sheep raising and grouse management began. Despite the suppression of their numbers, up to the 1960s at least four ancestral breeding sites were still occupied, but these fell vacant one by one until only a single tenacious pair remained. Circumstantial evidence relating to the latter stages of the raven’s decline pointed to an upsurge in the illegal laying-out of poisoned baits to kill foxes and carrion/hooded crows instead of the more traditional methods of control. From the late 1980s onwards, the species made an almost unbelievable comeback with up to eight nesting pairs in residence, some in locations not known to hold ravens in living memory.

Fig. 12.2 On the southern flank of the Fintry Hills, the Double Craigs are noted for their community of calcicole plants.

After a long winter, the far-carrying song of the first ring ouzel of the season is guaranteed to lift the spirit of anyone out and about on the hill in early April. Sad to say, however, in the last few years the numbers of ring ouzels have been steadily dropping, and favourite sites that could once be depended upon are now disappointingly silent. Usually the first bird to attract observer attention by its warning ‘chacking’ from a prominent position, the wheatear shows a strong preference for turf closely grazed by sheep and rabbits amongst the fallen boulders below the cliffs. The twite or mountain linnet on the other hand can be easily overlooked until one becomes familiar with the male’s ‘sweazy’ song. On the Campsie and Fintry Hills the twite’s favoured nesting habitat is a well-vegetated cliff out of reach of sheep, a good example being the steep east face of the Corrie of Balglass (Fig. 12.3) with its patchy covering of dark-leaved willow (Salix myrsinifolia) and eared willow (S. aurita). Differing markedly in their choice of habitat from the heather-moor nesting twite of the English Pennines, these low shrub-nesting birds of the southern foothills could well be direct descendants of those early colonists of the boreal scrub that covered these hills following the last glacial period.

Fig. 12.3 The Corrie of Balglass on the north face of the Campsies; a habitat for upland plants and birds in the Lowlands.

Two hundred years ago the impressive amphitheatre of the Corrie of Balglass was home to the southern foothills’ only nesting pair of golden eagles. Just the occasional eagle is seen on the Campsies these days, usually when the population of blue hares is at one of its periodic peaks. Another lost breeding bird of the area is the chough (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax). Reported as already rare on these hills by the 1790s, the ‘red-legged crow’ vanished as an inland species throughout the Clyde area soon after. Naturalists of the day attributed its retreat to the west coast to an increase in the number of jackdaws (Corvus monedula) taking over the chough’s nesting cliffs, although it is probable that another contributory cause was the run of severe winters that set in towards the end of the eighteenth century, seriously affecting food availability for this essentially insectivorous bird. Playing a part too must have been the move away from hill cattle in favour of sheep, depriving the chough of an invertebrate food source beneath the numerous cow-pats.

The Kilpatricks stand out from both the Campsie and Fintry Hills in the number of lochans and man-made reservoirs. In spring, Burncrooks Reservoir attracts several pairs of ringed plover and common sandpiper to nest around its wave-eroded stony edge. Some of the commoner species of waterfowl – including the occasional pair of feral greylag geese – and gull nest safely on its largest island. Close to Burncrooks is Kilmannan Reservoir, which has had a chequered history of use. Originally one of the very few natural water bodies in the Kilpatrick Hills, it was enlarged in the late eighteenth century to provide compensation water to the River Kelvin, which was being drawn upon to top up the newly opened Forth and Clyde Canal. The fact that the River Kelvin powered Glasgow’s meal mills at Partick is the reason why Kilmannan Reservoir is also known as the Bakers’ Loch. Ownership of Kilmannan by the British Waterways Board was relinquished in the late 1970s, when it was linked to Burncrooks and incorporated into the public water supply. Since then Kilmannan Reservoir has been subject to wide fluctuations in surface levels, adversely affecting the nesting success of its great crested grebes. The change in regime does appear to have favoured Kilmannan’s population of tiny waterworts (Elatine spp.), for exceptionally large carpets of these infrequently seen plants, together with the rare moss Bryum cyclophyllum, appear on the drying-out bed of the reservoir in summers when the water level is drawn down (Plate 14). At 310 m, the wind-sheltered western edge of the Lily Loch below Duncolm has several patches of the rare hybrid water-lily Nuphar x spenneriana, although neither of the parent plants (yellow water-lily and least yellow water-lily Nuphar pumila) appear to be present today.

Only small scattered pockets of blanket bog remain on the Kilpatricks, with much of the upper ground either planted with conifers or moor-gripped and drying out. Draining has been least successful in a rock basin hollow just to the north of the Lily Loch, where the two bog sedges Carex limosa and C. magellanica still hang on. Despite recent forestry planting, there are still extensive stands of ling heather. This is the chosen habitat of the merlin (Falco columbarius), which preys almost exclusively on small birds like the meadow pipit. The larger day-flying moths will also be taken by this smallest of falcons. In such wide open country a merlin territory can be difficult to locate, the few records available suggesting that tree-nesting in an abandoned crow’s nest is more frequent than a ground nest site on these moors. Golden plover and dunlin seem to have disappeared as nesting species on the northern Kilpatrick Hills, but curlew are still common along the moorland edge. On Pappert Muir, in the northwest corner of the Kilpatrick Hills, the heather merges with rough grazings partially covered with bracken and common gorse. In summer this heathland is ideal for nesting whinchat and stonechat, any black grouse present showing preference for areas with small clumps of trees.

The Luss Hills

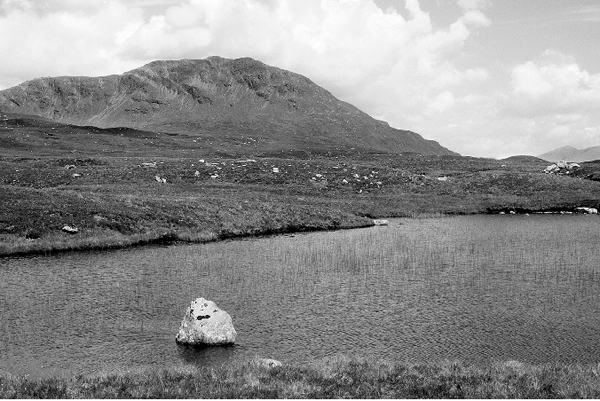

Just over the Highland Line on the west side of the loch, the rounded tops of the Luss Hills (Fig. 12.4) contrast with the irregular relief of the mountains beyond them to the north. It is on the Luss Hills that the botanist first meets up with the Highland schists, although at the southern slaty edge of the formation, mountain flowers are initially rather sparse on these mineral-poor rocks. Careful searching of the upland flushes and rills will, however, reveal the presence of alpine bistort (Persicaria vivipara), alpine meadow-rue (Thalictrum alpinum) and three-flowered rush (Juncus triglumis), all three of these relatively common upland species apparently absent from the foothills of the Clyde Lava Plateau only a short distance away. The most southerly cliffs – Corrie Cuinne at the head of Glen Finlas – offer mountain male fern (Dryopteris oreades), holly fern (Polystichum lonchitus), purple saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia) and an inland colony of sea campion (Silene uniflora). Although the sea campion is understandably considered a coastal plant, it too is as much a postglacial colonist as the other montane species, surviving in scattered upland localities where it has not been shaded out by woodland cover. Creag an Leinibh in Glen Luss adds alpine scurvy-grass (Cochlearia pyrenaica ssp. alpina), alpine saw-wort (Saussurea alpina) and the whortle-leaved willow (Salix myrsinites) to the list. Another upland plant, the northern buckler fern, finds shelter amongst the boulder scree below Beinn Eich on the opposite side of the glen. Doune Hill (734 m) above Glen Douglas has the most diverse montane flora of all the Luss Hills, with moss campion and Scottish asphodel (Tofieldia pusilla) reflecting the hill’s outcrops of calcareous schist.

Fig. 12.4 The Luss Hills on the southwestern fringe of the Grampian Highlands.

There are a few localised colonies of the scotch argus butterfly (Erebia aethiops) amongst the purple moor-grass in some of the glens, usually where the insect can gain a little shelter from the wind in a scattering of small trees. Upland birds tend to be rather thin on the ground, making it possible to walk over the closely grazed summits without seeing more than a distant glimpse of a wary hooded crow. On these hills the ornithologist must select the most profitable looking spots very carefully, such as choosing Creachan Hill with its eroding peat haggs as the best chance of picking up golden plover. Peregrine and raven are about, but tucked away in hidden ravines. Even the golden eagle has nested in one or two remote corners of the Luss Hills in years past and could well do so again.

The northern plateaux

The slow but continual breaking down of mica schist by weathering gives the southwest Grampian Mountains their characteristic moderately steep silhouettes. Slope erosion is much slower where there are outcrops of more resistant rock. A prime example is to be found on the southern flank of the Ben Lui–Ben Oss–Beinn Dubhchraig watershed ridge, where the gradient abruptly eases off into the high-level Caorann Plateau (Fig. 12.5). For the most part between 400 and 525 m, the plateau is underlain by a hard garnetiferous schist. Its mantle of blanket bog, dominated by ling heather, deergrass, cottongrass and purple moor-grass, is broken up by a mosaic of exposed knolls and ridges, in places covered by a dwarf-shrub heath of blaeberry, crowberry, cowberry and cloudberry. A feature of the area is the high number of lochans and pools – about 70 in all – scattered over the plateau. Although the vegetation in and around the peaty lochans and pools is generally rather sparse, the isolated Lochan a’ Mhadaidh (the lochan of the wolf) is one of the exceptions, with an aquatic flora that includes awlwort and Nordic bladderwort (Urticularia stygia), but best of all a large patch of the very uncommon least yellow water-lily.

Fig. 12.5 Studded with small lochans, the Caorann Plateau is Loch Lomondside’s premier habitat for upland waders.

Both approach glens to the Caorann Plateau from the Glen Falloch road are not without interest in themselves. In early spring the call of the ring ouzel still rings out from amongst the rowans that cling to the cliffs. Especially noteworthy is the occurrence of the very local pale butterwort. On Loch Lomondside this markedly western species is confined to the warmer south-facing slopes where ground water draining from mineral-rich rocks above seeps out of exposed peat below.

Red deer are usually to be seen on the Caorann, except during the warmer summer months when they move up to the ridge tops to pick up a breeze to escape the persistent attention from flies, or to seek out a north-facing late snow patch to cool off in the midday sun. From late September through October, the return of the stags to the plateau and surrounding glens is proclaimed by their ‘roaring’ as they challenge for the hinds during the rut. Only in the face of severe weather do they descend right down to the low ground to forage wherever they can. Of additional interest on the plateau to the visiting mammalogist is a high-altitude population of water voles, which extends all the way up to Loch Oss at 640 m. Despite the area’s high rainfall, the steep slopes immediately below the plateau ensure a rapid runoff of excess water, so that the voles’ tunnels beside the lochans and burns are only infrequently washed out. This is in marked contrast to their cousins along the Lowland river banks, where the voles are forced to migrate to higher ground to avoid the seasonal flooding. Mink have been observed following up the watercourses issuing from the plateau, showing all too clearly the potential threat of this alien predator to water vole colonies throughout their Loch Lomondside range.

In spring, the plaintive piping of golden plover and the trilling song of displaying dunlin captures the very spirit of the Caorann. Census figures confirm that in a good year, there can be up to 16 territorial pairs of golden plover and 14 pairs of dunlin. These relatively high densities of the two species on the plateau are quite atypical of Loch Lomondside as a whole. Snipe and common sandpiper are also present in small numbers. For the upland ornithologist, however, the blue riband wader is the occasional nesting pair of greenshank (Tringa nebularia) (see p. 192), although just as exciting for the observer concerned was the chance discovery of a displaying wood sandpiper in June 1968. But winter-like conditions are always waiting in the wings; and what would be just a spring shower lower down in the glens can be a blizzard at these altitudes. Periodic monitoring undertaken over a number of years has shown that the plateau’s wader population is very vulnerable to any prolonged deterioration in the weather conditions in May and June. When this occurs, few birds are able to rear young successfully.

Roughly 8 km to the southwest is another rewarding, yet seldom visited, locality for upland waders as well as the occasional pair of nesting red-throated divers (Gavia stellata) (Plate 15). The Maol Meadhonach–Maol Breac–Beinn Damhain Plateau is underlain by a complex of hard igneous rocks, exhibiting a similar terrain to the Caorann of glacially scoured knolls and gouged depressions occupied by shallow lochans. The flora of the plateau has been little studied, but bearberry (Arctostophylus uva-ursi) and dwarf juniper are both on record.

The mountains

The given summit heights of Loch Lomondside’s higher hills and mountains vary slightly according to which edition of the Ordnance Survey map is consulted. In the list below, the imperial measurements of the summit heights are taken from the out of print but still much used Loch Lomond and the Trossachs Tourist Map (1983), and are followed by the measurements from the most recent metric maps, on which spot-heights are rounded off to the nearest metre.

‘Munros’ (summits over 3,000 ft / 914 m) within the Loch Lomond catchment are:

The Highland fringe

Ben Lomond 3,194 ft (974 m)

The Arrochar range (in ascending order)

Ben Vane 3,004 ft (915 m)

Beinn Narnain 3,040 ft (926 m)

Ben Vorlich 3,093 ft (943 m)

Beinn Ime 3,318 ft (1,011 m)

The Glen Falloch range eastern group (in ascending order)

Beinn Chabhair 3,053 ft (933 m)

Beinn a’ Chroin 3,084 ft (940 m)

An Caisteal 3,265 ft (995 m)

Cruach Ardrain 3,428 ft (1,046 m)

The Glen Falloch range western group (in ascending order)

Beinn a’ Chleibh 3,008 ft (916 m)

Beinn Dubhcraig 3,204 ft (978 m)

Ben Oss 3,374 ft (1,029 m)

Ben Lui 3,708 ft (1,130 m)

There are also seven mountain tops over 2,500 ft (726 m), but only two – Meall an Fhudair 764 m and Beinn a’ Choin 770 m – are classed as ‘Corbetts’, which in order to qualify must have a drop of at least 500 ft (152 m) between the hill’s summit and any adjacent higher peak. This ruling disqualifies such fine hills as A’Chrois at 848 m in the Arrochar range, as the drop between its summit and beginning the ascent of neighbouring Beinn Narnain is only 107 m. Observed from most angles, however, A’Chrois appears as a well-defined individual peak in its own right.

The altitudinal zonation of the region’s mountain vegetation can be seen to advantage on the open ground above the forestry plantations on Ben Lomond, especially if viewed from the opposite side of the loch in late summer. At that time of the year the bracken on the lower slopes is just beginning to turn gold, succeeded up the hillside by the fading purple of the remaining ling heather. The heather gives way to the dark green of blaeberry where it is not hard grazed, followed in turn by the yellowing mat-grass merging into the partially vegetated thin soils and frost-shattered rock detritus at the very top. What is totally missing above today’s abrupt upper tree line is a montane shrub zone, which, throughout the Lomondside uplands, has long since vanished in the face of relentless browsing by domestic stock, first cattle and goats and then sheep.

The story of the scientific exploration of Loch Lomondside’s mountainous region begins on Ben Lomond – Scotland’s most southerly and Stirlingshire’s only Munro – with an ascent by the Reverend John Lightfoot on 13 June 1772, while gathering material for his Flora Scotica (1777). For the most part only the commoner mountain species were recorded by Lightfoot and his companion the Reverend John Stuart on that day, but it was enough to put Ben Lomond on the botanical map. Regrettably, the depredations of covetous collectors and nurserymen with an eye to profit which followed the book’s publication was to lead to the extirpation of several of the Ben’s rarer arctic-alpines. Such was the demand for trailing azalea (Loiseleuria procumbens) for example, that the asking price at the time was half a guinea per plant, more than a week’s wage for most. The former presence of some of the species that have apparently disappeared from Ben Lomond can at least be confirmed from preserved dried specimens in botanical collections, such as the rare mountain bladder fern (Cystopteris montana). Most intriguing of all of Ben Lomond’s ‘lost’ plants is a herbarium specimen of the Arctic bramble (Rubus arcticus), which has not been reported from the Scottish Highlands since the mid-nineteenth century. Although it is unlikely that all of the following species would be seen during the course of a single visit, montane flowering plants that still occur sparingly on the Ben’s higher slopes and rock ledges include alpine mouse-ear (Cerastium alpinum), downy willow (Salix lapponum), hoary whitlowgrass (Draba incana), alpine saxifrage (Saxifraga nivalis), alpine cinquefoil (Potentilla crantzii), sibbaldia (Sibbaldia procumbens), alpine willowherb (Epilobium anagallidifolium), spiked woodrush (Luzula spicata), black alpine sedge (Carex atrata), glaucous meadow-grass (Poa glauca) and the alpine meadow-grass (P. alpina), in addition to most of the upland plants already listed for Loch Lomondside’s southern hills. Hardier species growing on the summit ridge, where the sub-alpine soils are poorly developed and the protective snow cover is frequently blown away by strong winds – dwarf willow, dwarf cudweed (Gnaphalium supinum), stiff sedge (Carex bigelowii), three-leaved rush (Juncus trifidus), alpine clubmoss (Diphasiastrum alpinum) and the woolly fringe moss – are adapted to withstand repeated freeze-thaw winter temperatures and exposure to wind by their prostrate, cushion or low tussock modes of growth. Of the high-level flowerless plants, the high northeastern corrie of Ben Lomond (Fig. 12.6) has at least three montane lichens at the southern edge of their British range – Pertusaria dactylina, Stereocaulon tornense and Micarea subviolascens – the last two associated with late snow patches, which in the corrie can persist until late June. The snow bed moss Kiaeria starkei is also present, along with meltwater-fed greyish carpets of the liverwort Anthelia julacea. These tiny lichens and bryophytes were almost certainly amongst Lomondside’s earliest colonists in the wake of the final retreat of glacial ice, providing a foothold for a succession of other plants and the botanist with a link through time to a much colder age.

Fig. 12.6 The east face of Ben Lomond rises steeply above the old steading of Comer – birthplace of Mary MacGregor, wife of Rob Roy.

It was after his second tour of Scotland in 1772 that zoologist Thomas Pennant became the first traveller to report that ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) (see p. 193) were to be found on the upper slopes of Ben Lomond. The southwest ridge leading down from the summit appropriately bears the bird’s name. Another visitor, a nineteenth-century excursionist who made it to the top, wrote of ravens waiting patiently about the summit to feed on the discarded scraps of his repast. There are a number of other early records of Ben Lomond birds scattered in the travel and ornithological literature, the most unusual a snowy owl (Nyctea scandiaca) which, according to Robert Gray in his Birds of the West of Scotland (1871), was regularly observed in the early winter of 1869. The owl made frequent descents to the low ground and appeared to be feeding almost entirely on grouse. Although forestry plantations have covered over most of the lower purple moor-grass slopes, the scotch argus butterfly can still be found locally immediately above Ardess. However, the main attraction to the butterfly enthusiast is the presence further up in the southwest corrie of the small mountain ringlet (Erebia epiphron) (see p. 191). The moths of the higher ground are very underworked despite Ben Lomond’s accessibility, but to be fair the sheep-degraded state of the heather and blaeberry offers little incentive for visiting lepidopterists to devote their time. Amongst the upland species recorded to date are the grey mountain carpet (Entephria caesiata), the yellow-ringed carpet (E. flavicinctata) – the larvae apparently feeding exclusively on yellow mountain saxifrage on Ben Lomond – and a montane grassland pyralid moth Udea uliginosalis.

Beinn Ime, the highest of the Arrochar Hills, has a mountain flora much akin to Ben Lomond. Although two or three species already listed for Ben Lomond are apparently absent, the botanist ascending Beinn Ime on its northeastern side is compensated by some fine flushes of russet sedge (Carex saxatilis), alpine lady fern (Athyrium distentifolium) and the only known station in the district for the Arctic mouse-ear (Cerastium arcticum) (Fig. 12.7). The montane lady’s mantles Alchemilla glomerulans and A. wichurae are also known from this hill. Chestnut rush (Juncus castaneus) was reliably reported in the past and, although there are no modern records, further careful searching and a little luck could well lead to this species’ reinstatement. Before moving on, those of a nervous disposition should perhaps be warned that the summit has a reputation for being haunted. In Highland Gathering (1960), ornithologist Kenneth Richmond recalled how, when looking for ptarmigan on a winter’s day, he met up with the Old Man of Beinn Ime who left no footprints in the snow, the reason he insisted he would never go back there again.

Easily reached even in the nineteenth century by making use of the steamer services on the loch, Ben Vorlich was a favourite haunt of that doyen amongst Scottish naturalists, John Hutton Balfour, Professor of Botany at the University of Edinburgh. Balfour’s diaries for 1846–78 confirm that he often took his students there on summer field excursions. One montane plant regularly found and entered into his meticulously kept journal was the interrupted clubmoss (Lycopodium annotinum). Ben Vorlich is the most southerly extant site for the species in Scotland. Another good find of Balfour’s on this hill was the spring quillwort (Isoetes echinospora), an aquatic plant of nutrient-poor mountain pools. Amongst several other famous names attracted to Dunbartonshire’s highest mountain was the Reverend C.A. Johns, best known as author of Flowers of the Field which passed through numerous editions. In one of his other popular works, Botanical Rambles (1846), the umbrella-carrying cleric tells us that on reaching the summit, he enlivened his sandwiches with the tart leaves of mountain sorrel (Oxyria digyna). A second distinguished man of the cloth, the Reverend E.S. Marshall, was to add mountain scurvy-grass (Cochlearia micacea) and a high-level form of yellow rattle (ssp. borealis) to Ben Vorlich’s already extensive plant list.

Fig. 12.7 The Arctic mouse-ear – which occurs on Beinn Ime – is very uncommon in the southern Highlands.

Contrasting with the moderately calcareous rock outcrops, which occur here and there on the hills and mountains already mentioned, are the acidic schists and hard igneous intrusions of the Meall an Fhudair–Troisgeach ridge near the head of the loch. This is the best locality in the district to look for the trailing azalea, although it is a plant of rock crevices rather than a component of a stony ground community as on Scotland’s granite hills further north. A generally uncommon species in the southwest Highlands, the dwarf cornel (Cornus suecica) grows in late snow lie hollows on Troisgeach’s northern face. Troisgeach is also one of the few known sites in the area for the small and inconspicuous bog orchid. A few pairs of golden plover are thinly scattered over the summit ridge in summer, but with most of the ridge below 726 m, the other attraction is as one of the least exhausting to reach haunts of ptarmigan on Loch Lomondside.

Beyond the old inn at Inverarnan, where many of the early botanists regularly stayed, Glen Falloch offers a number of opportunities to familiarise oneself with the region’s montane flora. It should be noted, however, that the really productive ground of some of these West Perthshire mountains lies on their northern faces in the catchment of the River Tay, outwith the Loch Lomond area described here. Beinn a’ Chroin, An Caisteal and Cruach Ardrain in the eastern block were all well worked by the indefatigable Victorian botanists after the railway link from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Crianlarich near the head of Glen Falloch was completed in 1873. Included among the many arctic-alpines that fell to their grasp were reticulate willow (Salix reticulata) and alpine woodsia (Woodsia alpina) (see p. 191), together with several endemic mountain hawkweeds (Hieracium spp.). Beinn Chabhair – the only other eastern Munro – never received the same attention in the past because of its distance from the railway station at Crianlarich. Yet the hill is not without botanical interest, as latter-day records of sheathed sedge (Carex vaginata) and chestnut rush show.

To the Munro-bagger, western Glen Falloch offers the most challenging ridgewalk in the district – three (even four at a push) major peaks attainable from the one ascent. The first Munro in line, Beinn Dubhchraig, is blessed with a south-facing, high-level exposure of Loch Tay Limestone, most importantly rendered coarsely crystalline and crumbly through contact with the metamorphic schists. This ‘sugar’ limestone is literally crammed with choice plants, not least the rock speedwell (Veronica fruticans), mountain willow (Salix arbuscula) and the easily overlooked hair sedge (Carex capillaris). Below the exposure, the well-drained and invertebrate-rich limestone soils are inhabited by Loch Lomondside’s highest known moles. The mole’s ability to thrive at such altitudes in ground that can be frozen solid, often for weeks at a time, is extraordinary. Common frogs, which breed in the small pools, adapt to the usually low summer temperatures at these heights by the tadpole stage taking two years to complete.

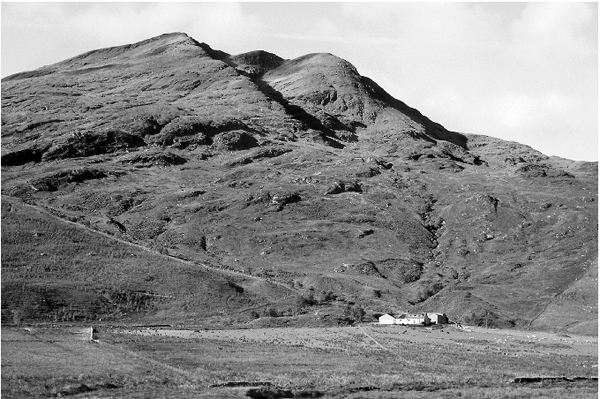

Rock ledges in the more calcareous schist of Beinn Dubhchraig provide further additions to the region’s mountain flowers, notably the semi-parasitic alpine bartsia (Bartsia alpina) and a large-flowered variety of northern rock-cress (Arabis petraea), which leading botanist George Claridge Druce named grandiflora from material he had gathered on these hills. From February onwards a pair of ravens regularly occupy the rather barren-looking cliffs above Loch Oss (Fig. 12.8). The advantage to the carrion-dependent ravens in such an early start to their breeding cycle is the frequency of winter casualties amongst the red deer and sheep. At 850 m (2,790 ft), this is the highest raven site in the district, and the nest is lined thickly with sheep’s wool to prevent the eggs chilling in the harsh conditions. Near the summit of Beinn Dubhchraig and that of neighbouring Ben Oss are found the diminutive cushions of mossy cyphel (Minuartia sedoides) – the region’s only montane flowering species that is exclusively alpine (that is, does not also occur in the Arctic) – together with several uncommon to nationally rare liverworts indicative of the high altitude: Scapania nimbosa, S. ornithopodioides (both western in their distribution), Anthelia juratzkana, Nardia breidleri and Moerkia blyttii, the last one in particular associated with late snow lie. West of Ben Oss, only the grassy south face of Ben Lui falls within the Loch Lomond catchment, which is almost invariably ignored by visiting botanists in preference for the well-known floral delights occurring on the rock faces outcropping on the Orchy and Tay sides of the hill. The unexpected discovery of high-level flushes with such rarities as alpine rush (Juncus alpinoarticulatus) and false sedge (Kobresia simpliciuscula) in Ben Lui’s southern corrie, previously considered too dull to repay detailed exploration, clearly illustrates that seeking out the neglected parts of even the most regularly visited areas can bring its rewards.

Fig. 12.8 Loch Oss; an ice-gouged corrie lochan or cirque lake at the foot of Beinn Dubhchraig.

Finally, Meall nan Tighearn (739 m) in the remotest western corner compensates the mountain botanist for its lesser height in having an outlying outcrop of the Lawers calcareous schist, on this hill overlying the more acidic garnetiferous schist through over-folding of the Tay Nappe. In the extremely wet conditions and well out of the reach of grazing animals, some of the cliff faces are completely draped in a luxuriant curtain of vegetation. These ‘hanging gardens’ are principally made up of plants normally associated with lower ground, including globeflower, wood crane’s-bill, meadowsweet, angelica and water avens. A good proportion of the flowering species of moderate altitude already referred to in this chapter are represented on this hill, but the addition of the strict calcicole dwarf shrub mountain avens (Dryas octopetala) points to the lime richness and friable nature of the Lawers schist. At least one shady cleft well up the eastern face of Meall nan Tighearn conceals the rare mountain bladder fern, one of the plants now lost to Ben Lomond.

The community of crag-nesting birds in these mountains is very similar to that already described for the scarps of the southern foothills, but with the addition of the golden eagle (see p. 193). Another upland bird, but not usually thought of as a Loch Lomondside species, is the dotterel (Charadrius morinellus), an attractive small wader that in summer is more or less confined to Scotland’s highest mountain massifs. At the time of their spring migration, dotterel on passage are occasionally seen on Ben Lomond and the Luss Hills, but breeding almost certainly took place on one occasion. In July 1979, a male bird was observed on the stony summit ridge of Ben Oss performing its characteristic distraction display of shuffling along the ground with trailing tail feathers and outstretched, quivering wings, a performance intended to entice potential predators away from its eggs or small young. Sightings of the snow bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) on Loch Lomondside during the breeding season are equally rare, although there are a few spring records of singing males being heard on the high cliffs of Ben Vorlich and A’Chrois. Following a report of a flock of over 500 snow buntings wintering at the head of Glen Luss towards the end of 1988, a pair was observed on the adjacent Doune Hill in July of the following year. However, proving that the odd pair of ‘snowflakes’ may occasionally stay behind to nest in some remote Lomondside corrie is a challenge still waiting to be met by the energetic ornithologist prepared to cover extensive areas of suitable terrain.

Fig. 12.9 Now very rare in Britain, the alpine woodsia has one of its strongest colonies in the Loch Lomond area.

Some notable upland species

The alpine woodsia (Fig. 12.9) is both one of the smallest and rarest of our native ferns. Intolerant of competition from the larger mountain plants, it favours fissured calcareous rock which it shares with little more than a few cushion mosses. Much sought after by collectors during the Victorian fern craze, alpine woodsia has been reported from three different hills within the Loch Lomond catchment area, one population quite exceptional for its large size. Numbers of plants do vary at this site, for the species is particularly vulnerable to desiccation in dry summers. The best season on record was 1990, when 340 separate tufts of the fern were counted, making it a contender for the largest individual colony in Britain of this now legally protected species.

The small mountain ringlet butterfly (Plate 16) population in Scotland is concentrated in the Grampian Highlands, with a scattering of sites throughout the Glen Falloch range. An isolated colony persists on Ben Lomond, the butterfly being most readily found in the southwestern facing corrie at around 500 m. Overwintering as a caterpillar deep within a dense tussock of mat-grass often covered by snow, the butterfly emerges towards the end of June, but can be up to a month later if the weather is poor. Mountain ringlets fly only in sunshine, their dark coloration maximising rapid absorption of heat. With the recent changes in the region’s climatic pattern, the effect of the greater frequency of overcast skies on a mountain species whose breeding cycle is dependent on summer sunshine gives cause for concern.

Fig. 12.10 More than once threatened with extinction, the peregrine population has recovered in most parts of Loch Lomondside (Don MacCaskill).

On the very southern fringe of its summer range in the central Highlands, the black-throated diver (Gavia arctica) has only one regular breeding site on Loch Lomondside. A combination of fluctuating loch levels – which all too frequently wash out the birds’ nest at the water’s edge – and fishermen in boats inadvertently preventing them from incubating their eggs, together ensure that the pair is rarely successful in rearing young. Up to four pairs of red-throated divers breed at suitable sites in the region, including a man-made reservoir. It is significant that the use of boats by anglers is forbidden on this strictly controlled water, and the divers are able to nest and rear their young undisturbed.

As a breeding species, the greenshank has only a tenuous hold on the Loch Lomond area and may not nest every year. Their presence in summer amongst the peaty lochans on the Caorann Plateau was suspected for some time, but it was not until 1977 that small young were actually seen. Not only is the Caorann the greenshank’s most southerly nesting site in Britain, at over 450 m it also appears to be the highest in the western Highlands.

No bird in the area has experienced changing fortunes at man’s hands more than the peregrine (Fig. 12.10). Initially highly esteemed and zealously protected for the ancient art of falconry, it twice faced extinction; first by direct persecution in the interests of game preserving, followed by indirect poisoning through a build-up of the agricultural insecticides dieldrin and DDT entering the food chain. Southern Loch Lomondside would not be considered amongst the most intensively managed farmland in Scotland, yet the levels of dieldrin residues found in locally recovered peregrine corpses were higher than any others recorded in Britain. So widespread was the effect of pesticide poisoning, that throughout the region during the five year period 1966–70, only one pair was known to rear young. Following legislation restricting certain uses of these toxic chemicals, the recovery in the peregrine population since the mid-1970s has been remarkable. In one favoured part of the southern foothills, where prey is abundant in the fertile valleys below, up to five pairs have been recorded nesting within a linear distance of 9.6 km, giving a mean distance of only 2.4 km between the occupied eyries. This is one of the highest densities of breeding peregrines recorded not only in this country, but in Europe.

The golden eagle has become the symbol of the Scottish Highlands; the very first sight of one of these magnificent raptors soaring effortlessly over a precipitous crag is an unforgettable experience. Their bulky nests are reoccupied and renovated early in the year before winter has lost its icy grip, almost always at traditional sites that have a long history of occupation. Although there is only one regularly breeding pair of eagles, in good years three nesting pairs have been recorded. Like the raven, most of the eagle’s food in the Loch Lomond Highlands is obtained from deer and sheep carrion, for there are few blue hares to hunt on these rain-soaked western mountains. Eagles are occasionally seen patrolling the upper slopes of Cnoc (492 m) at the head of Glen Sloy, where there is a very isolated, high-level colony of rabbits.

Whereas a distant golden eagle may sometimes by glimpsed by visitors reluctant to stray too far from their cars, on Loch Lomondside the ptarmigan will be seen only by those prepared to make the effort to reach the high ground. The most arctic of all the resident birds, the ptarmigan was undoubtedly one of the first species to recolonise Scotland at the end of the ice age 11,000 years ago. Living most of the year round in the boulder-strewn corries, they survive the winter by feeding on heather and blaeberry shoots protruding through the thinner snow on the windswept ridges. White as the snow itself in winter and mottled as the lichen-covered rocks in summer, the colour and texture of the ptarmigan’s seasonal plumages blend perfectly with their background. Loch Lomondside is at the southernmost edge of the ptarmigan’s breeding range in Britain, small coveys occurring on most if not all of the Munros. The species does appear to have been more widespread in the district up to the middle of the last century, from when there is a published account of ptarmigan shooting in summer on the Luss Hills. Although already in decline by then, the extent of ptarmigan habitat on the summits of these lower hills was probably still sufficient, but with further burning, sheep grazing and trampling, the heathy vegetation was eventually replaced by grassland offering little feeding and protective cover for the birds. Climatic warming leading to a reduction in winter snow on the mountains will inevitably restrict the bird’s distribution still further.