13

The Long Struggle for Nature’s Place

‘In calling attention to special areas, we would begin by emphasising

particularly the entire Loch Lomond area. It is not alone because of

its unique scenic beauty that Loch Lomond is of importance to the

people of the West of Scotland; the whole area, comprising as it does

features of mountain, river, lake and island landscape, constitutes an

almost unequalled field for the study of natural history.’

Submission to the Clyde Valley Regional Planning Committee

by the Glasgow & Andersonian Natural History Society (1945)

‘The Bonny Bonny Banks of Loch Lomond’ must be one of the best-known songs the world over, for it would seem that just about every one of the two million or more visitors each year is familiar with at least the opening lines of the chorus which tell of taking either the high road or low road back to this internationally renowned area. Yet there is another road – one that has proved long and stony – that has been slowly making its way towards recognition of Loch Lomondside as a living heritage landscape, a national asset of which Scotland can feel justifiably proud.

Although pristine areas of wild country have been set aside for birds and beasts of the chase since the time of the medieval kings, measures to preserve Scotland’s rich diversity of breathtaking scenery and abundant wildlife to refresh both body and mind of all the people and not just as a playground for the privileged few are a relatively modern concept. Over the last hundred years or so, moves to protect the nation’s finest landscapes from exploitation have become inextricably linked with calls for a system of National Parks, to safeguard in perpetuity the finest tracts of unspoiled countryside together with their dependent flora and fauna. Focusing down to just one region, this chapter looks back at some of the milestones – both successes and setbacks – in the progress of the conservation movement on Loch Lomondside.

The first stirrings

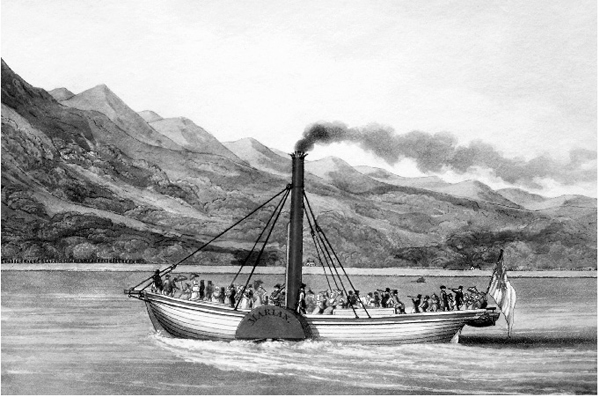

One of the earliest protests at what was seen as the despoliation of Loch Lomond came in the early nineteenth century with the introduction of the first steamboat service. Francis Jeffrey, a leading Scottish advocate who frequently stayed at Stuckgowan House overlooking the loch, felt compelled to complain when the small wooden-hulled paddle-steamer Marion (Fig. 13.1) began regularly to ply its waters in 1818. The steamer’s ‘hissing and roaring’ he considered, vulgarised the scene. It was probably this early development of popular tourism unfolding on his very doorstep, together with the sweeping changes taking place in agriculture and the advent of conifer plantation forestry, that prompted local man John Colquhoun to publish ‘A Plea for the Wastes’ in his book Rocks and Rivers (1849), which began with an impassioned appeal for the retention of the Highland’s wilderness character. After years of playing an active role in the impoverishment of Loch Lomondside’s wildlife as a sportsman-collector, in this at least Colquhoun was very much ahead of his time.

Fig. 13.1 Launched in the early nineteenth century, the Marion was the first in a long line of recreational paddle-steamers on the loch (Author’s collection).

Another half century passed before the idea of setting aside a representative example of the country’s relatively untouched wild land was aired again. In a landmark essay entitled ‘A National Park for Scotland’, first published in 1904 and updated in 1909, Charles Stewart of Appin, Argyllshire, proposed not only protected status for a large tract of the western Highlands possessing a natural beauty and grandeur in a high degree, but for the strict preservation of the natural fauna within its boundaries. With discussions then underway on the potential for state-backed afforestation of the Scottish Highlands, Stewart saw an additional reason for the establishment of a park system in order to preserve those wild animals of the open moorland and hillside which would be threatened by huge areas of plantation forestry.

The first proposal for designating land specifically for nature conservation in the Loch Lomond area came from the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves, which was founded in 1912. Ben Lui, which just touches the area’s northwestern fringe, was included in their list of potential reserves in Britain compiled in 1915. Although not stated, Ben Lui was almost certainly nominated by one of the society’s driving forces – the botanist George Claridge Druce – who had previously made a study of this fine hill.

The Addison Report

In 1929, overtures were made to Government by several countryside organisations, including the newly formed Association for the Preservation of Rural Scotland, requesting an inquiry into the need for a series of National Parks in Britain. The Government response was the setting up of a National Park Committee under the chairmanship of Dr Christopher Addison, then Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture. Objectives included the examination of proposals for the safeguarding of areas of exceptional national interest and nature sanctuaries for the protection of flora and fauna.

With the exception of the Cairngorms, the Report of the National Park Committee (Cmd. 3851) published in 1931 did not consider any particular area in Scotland for either National Parks or nature sanctuaries, but did append the suggestions made by witnesses to the Committee. Those listed included sites only peripheral to Loch Lomond, such as the Trossachs, proposed as a National Park by the Ramblers Federation. As nature reserves, the British Correlating Committee for the Protection of Nature (made up of representatives from a number of scientific bodies) put forward Ben Lui for mountain plants and the Ardgoil Peninsula in Cowal for birds.

The early 1930s were a time of financial stringency in the country, with no steps taken by Government to implement any part of the Addison report. This lack of action galvanised the voluntary bodies into forming a Standing Committee on National Parks in 1934 to keep alive public interest and support. Amongst several areas in Scotland proposed for National Park status by the Standing Committee in the following year were some of the wilder parts of Argyll and central Perthshire, but nothing for Loch Lomondside.

Events on Loch Lomondside during the 1930s and 1940s

A move that could have given Loch Lomondside a flying start in landscape and wildlife conservation occurred in the summer of 1930, when the Duke of Montrose approached the Chancellor of the Exchequer with the offer of the Rowardennan Estate – which included Ben Lomond – in lieu of death duties. It was proposed that once the land transfer was complete, the Ben Lomond area was to be given National Park status. Seen now as a golden opportunity missed, this offer to hand over Rowardennan Estate to the nation was turned down. Despite fears fanned in the press that the whole area would be sold off abroad along with other national treasures, the land was eventually purchased by a Scottish industrialist who continued its use as a sporting estate.

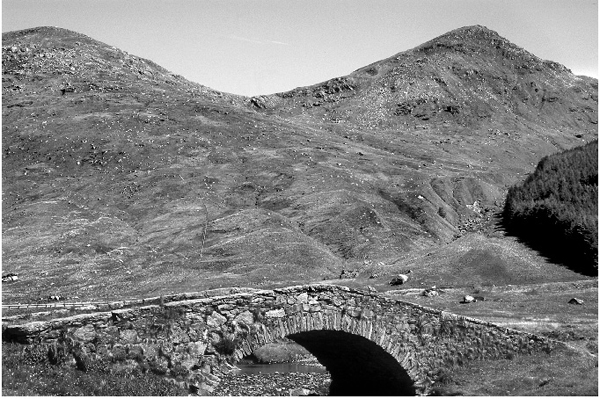

The chance gone to create Britain’s very first National Park in Scotland, the Lomondside peaks of Beinn Ime (Fig. 13.2), Beinn Narnain and A’Chrois were included in the Forestry Commission’s 235 km2 Argyll National Forest Park when it was formally opened in May 1937. This was the first of any type of large-scale park in Britain. Although the primary use of the plantable land remained the commercial production of timber, it was recognised that there were also opportunities for both recreation and nature conservation. An extension eastwards to the very shores of Loch Lomond took place in 1966, when the Stronafyne Estate north of Arrochar was purchased by the Commission, enabling a linkup of the Argyll Forest Park (the prefix ‘National’ now dropped) with Kenmore Wood near Tarbet which had been acquired earlier.

Not everyone felt at ease with the prospect of conifer plantations spreading all over the Scottish hills. During the mid-1930s, individual members of the Association for the Preservation of Rural Scotland expressed their concern that large-scale forestry operations such as those underway in the Aberfoyle area would transform entire landscapes to their detriment. However, the general consensus at the time was that mile upon mile of coniferous trees planted in regimented ranks could hardly materialise in a country with such varied topography as the Highlands. The result was that an agreement between the amenity and rural conservation bodies with the Forestry Commission over restricting blanket afforestation in selected areas, such as those already formalised in parts of the Lake District in England and Snowdonia in Wales, was considered unnecessary in the equally scenic regions of Scotland.

Fig. 13.2 At 1,011 m, the summit of Beinn Ime is the highest peak in the Argyll Forest Park.

Late 1944 saw the first major environmental battle for Loch Lomondside, which followed the publication of the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s plans for a massive development based on Loch Sloy, a remote lochan in the Arrochar Hills. Amongst the objectors to the project were representatives of the landowner on the grounds of loss of amenity and Dunbarton County Council who submitted a case for reserving the Sloy catchment for the primary water needs of the county. Opponents to the scheme also stressed the visual impact of siting an electric generating station at Inveruglas beside Loch Lomond. In rejecting the environmental evidence presented, the chairman of the ensuing public enquiry gave his opinion that the Inveruglas site selected for development was not in itself a noted beauty spot, being a steep and scrub-covered mountainside with no special features to commend it; the generating station’s multi-pipeline intake when treated with camouflage paint would not be obtrusive and in time would be concealed by planted trees; the station itself was to be a very modest structure and would not in any appreciable degree affect the natural beauty of the area. Posterity, however, has not judged these conclusions in quite such a favourable light. By no stretch of the imagination can it be claimed that the power station and its huge intake pipes have successfully blended into the landscape, even after half a century (Fig. 13.3). Nor could the associated double row of electric pylons heading towards Glasgow be hidden from general view once they reached the more open ground of Glen Fruin. Above all, the wild solitude of Glen Sloy was lost for ever. Years after the completion of the project, complaints still rumbled on over the industrial debris abandoned at a work site in Coiregrogan Glen.

Fig. 13.3 The Loch Sloy hydro-electric generation station at Inveruglas.

The Ramsay Reports and the Clyde Valley Regional Plan

Despite the dark shadow cast by the Second World War, the Association for the Preservation of Rural Scotland was able to set up a Scottish Council for National Parks in 1942. Acting for about 30 interested bodies, the Council pressed the Scottish Secretary of State for an assessment of potential park areas in the country. Importantly, the Council’s own nominations included Loch Lomondside for the first time. Resulting from these representations, a Scottish National Parks Survey Committee was appointed in January 1944 under the chairmanship of Sir Douglas Ramsay. The Committee’s remit was to identify and survey the most suitable areas for designation as National Parks. When National Parks: A Scottish Survey (Cmd. 6631) was published in 1945, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs headed the list in order of priority.

The selection of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs area as a potential National Park was well received by the Clyde Valley Regional Planning Committee, whose remit included Loch Lomondside, although they did not agree with the park boundaries proposed, which more or less followed the loch’s western and southern shores. One of their concerns was over a Loch Lomond Draft Planning Scheme prepared by Dunbarton County Council, which zoned the loch’s southern banks for residential development. The Regional Planning Committee’s favoured boundaries included the improved farmland to the south of the loch, all of the surrounding hills, together with a link-up to the existing Argyll Forest Park. For their own Clyde Valley Regional Plan published in 1946, the Committee turned to the Glasgow and Andersonian Natural History Society for comment on the boundaries to the plan and the identification of key wildlife sites. In their response, the Society recommended for inclusion within the plan all of the loch and its islands, the entire montane area to the north plus the Kilpatrick, Campsie and Fintry Hills to the south. Ballagan Glen and the Endrick Marshes were among several high quality geological and wildlife sites individually named. The Society added to their submission that the setting-up of local or National Nature Reserves within the defined area would meet with their full approval.

The follow-up to the Scottish National Parks Survey Committee report was the appointment of a second committee, again under the chairmanship of Sir Douglas Ramsay, to advise on the administrative and financial requirements of a National Parks system in Scotland. In the second Ramsay report National Parks and the Conservation of Nature in Scotland (Cmd. 7235) published in 1947, the Loch Lomond–Trossachs area remained the Committee’s first choice. In the meantime, however, powerful vested interests had gathered together to oppose the very idea of National Parks in Scotland. This came not only from the major landowners unwilling to relinquish absolute control over their estates, but also from the hydro-electric and forestry industries who saw the Committee’s recommendations as liable to sterilise large tracts of Scotland from future development. Even some conservationists expressed their reservations, fearing that National Park status might attract a rash of tourist-led developments aiming to cash in on the growing demand for recreational and leisure activities, rather than generate genuine public concern for the natural environment. In the face of this combined opposition the outcome was inevitable. The Government accepted the case for the creation of National Parks in England and Wales, but Scotland was passed over in the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. Minimum protection was afforded to Scotland’s special areas by the introduction of National Park Direction Orders (one of which covered Loch Lomond and the Trossachs), whereby the Secretary of State was empowered to scrutinise any development proposal falling within each order’s designated boundaries.

The Ritchie Report and the Nature Conservancy

At the very first meeting of the second Scottish National Parks Committee held in February 1946, a supporting Scottish Wildlife Conservation Committee was appointed under Professor James Ritchie. The Ritchie Report Nature Reserves in Scotland (Cmd.7814) published in 1949 listed a number of proposed nature reserves and conservation areas in Scotland. No part of Loch Lomondside was included amongst these sites. Unaccountably, even Ben Lui on the northwestern fringe was left out. Just to the east of Loch Lomond, however, the Ritchie Committee suggested the eastern end of Loch Ard near Aberfoyle as a National Park Reserve, the designation to be given to any nature reserve situated within a National Park in Scotland. Gartrenich Moss nearby – which was considered the least disturbed of a series of raised bogs in the Forth Valley – was put forward as a Nature Conservation Area to preserve the site from harmful developments. Neither recommendation was adopted. Gartrenich was subsequently acquired by the Forestry Commission, the moss drained and planted with conifers.

Despite National Parks for Scotland having been rejected by Government, it did accept the Scottish Wildlife Conservation Committee’s recommendation of a representative series of National Nature Reserves throughout the country, together with creation of a biological service to protect, administer and manage the reserves. This wildlife service was to be a Great Britain body, not separate from England and Wales as some had advocated. The Nature Conservancy (later, the Nature Conservancy Council) was founded by Royal Charter in 1949, a programme of National Nature Reserve acquisition beginning almost immediately. The new organisation was also given the responsibility of notifying to local planning authorities all sites regarded as having special scientific interest (SSSIs) within their administrative boundaries. In general these were often very small areas, but sufficiently important to need some statutory protection against developments likely to damage their wildlife or physical interests. Loch Lomondside’s Conic Hill, with its exposures of the Highland Boundary Fault zone, was notified as a geological site in 1951, one of the very first SSSIs in Scotland.

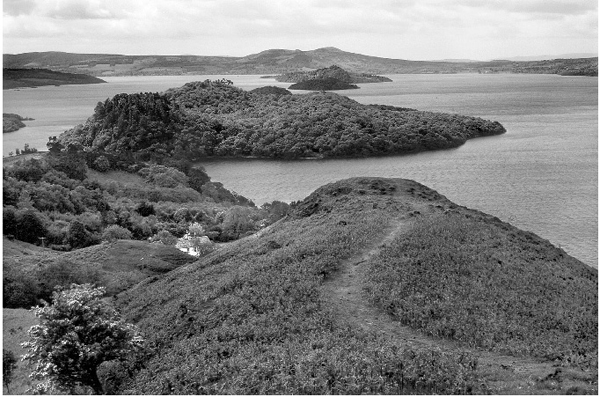

The National Nature Reserve potential of Loch Lomond’s southeastern group of wooded islands quickly attracted the newly formed Nature Conservancy’s attention, in particular the floristically diverse Inchcailloch (Fig. 13.4), which was used for teaching purposes by the Botany Department of Glasgow University. Clairinsh was also earmarked, the reversion of the island’s oak coppice back to semi-natural high forest more advanced than in any other formerly managed woodland in the area. It was Clairinsh in fact which was the first to gain National Nature Reserve status, declared in July 1958 by agreement with the island’s owners, the Buchanan Society. At this point the Nature Conservancy was confronted with applications for housing developments on Inchcailloch and its neighbouring island of Torrinch. Clearing the earmarked building site of trees actually began on Inchcailloch, but felling was brought to a halt by Stirling County Council imposing a Tree Preservation Order, a standoff only resolved by the Conservancy’s purchase of the island from the would-be developer. The Nature Conservancy’s now committed interest in Loch Lomondside was also drawn to the Endrick Marshes on the adjacent mainland. Ornithologically, not only was the area at the confluence of several routes used by migratory birds, but regular counts of wintering wildfowl from 1948 had shown the Endrick Marshes to harbour numbers of regional importance. The Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve, made up of Inchcailloch, Clairinsh, Torrinch, Creinch and the Aber Isle, together with the grazing marshes south of the River Endrick, was declared on 4 December 1962. The waterfowl habitat of the reserve was further recognised in 1976, when it was designated under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance. With subsequent extensions on the mainland to encompass all of the Endrick Marshes in the lower flood plain of the river, the extent of the reserve stands at 441 ha.

Fig. 13.4 Only just offshore, Inchcailloch is the most accessible of the five islands in the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve.

A countrywide review of existing and potential conservation sites undertaken in the 1970s identified two other Loch Lomond islands – Inchlonaig and Inchmoan – as being of National Nature Reserve standard, although to date, no firm steps have been taken towards their inclusion within the existing reserve. Ben Lui National Nature Reserve (374 ha) was declared in April 1961. Although there have been several major extensions since then, only the reserve’s eastern extremity on Ben Dubhchraig falls within the Loch Lomond catchment area.

Barely had the Nature Conservancy become established in the area, when it was faced with a proposal for Scotland’s largest reservoir development – the Loch Lomond Water Scheme. To increase the reservoir’s storage capacity, the plan was to hold the water level at 27 ft (8.2 m) OD by means of a barrage across the only outlet to the loch. This would have raised Loch Lomond’s mean annual water level by about 2 ft (0.61 m), with loss of the important shore zone plant communities of the reserve and elsewhere. Following objections from the Conservancy, together with other loch users and lochside residents, the height of the crest barrage across the River Leven was agreed at a compromise 26 ft (7.9 m) OD. Despite the overall picture having been complicated by increased rainfall experienced over the same period, most riparian property owners on both the mainland and islands remain adamant that the artificially raised water level is responsible for the unprecedented rate of shore erosion witnessed since the scheme became operational in 1971 (Fig. 13.5).

The Queen Elizabeth Forest Park

By late 1949, the Rowardennan Estate (including Ben Lomond) was again facing sale to meet death duties. This time the Government did step in to purchase the estate through the National Land Fund. Set up just after the Second World War, the National Land Fund was specifically aimed at acquiring areas of high scenic value. Such land was to be dedicated to those who died in the conflict and made available in perpetuity to everyone seeking the peace and tranquillity of the countryside. Initially it seemed the estate would be entrusted to the care of the National Trust for Scotland, a body that was empowered to hold land. Founded in 1931, the Trust already had a presence on Loch Lomondside, having been gifted two small islands – Bucinch and Ceardach – in 1943. In the event, the estate passed to the Forestry Commission, and the land was incorporated into the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park, which officially opened on 19 June 1954. When it came to the preservation of the area’s natural beauty, it cannot be said that during the early years of the park’s existence the Commission’s management on Loch Lomondside fully lived up to the ideals and expectations of the National Land Fund. Scant attention was paid to landscape design, with straight-edged blocks of foreign conifers laid out unsympathetically to the terrain. With the planted trees in each block even-aged, harvesting at commercial maturity would be by clear-felling, leaving behind a scene of ugliness impossible to disguise. The Forestry Commission’s treatment of the large stands of former coppice oak woodland within the park also left something to be desired. Classified in a woodland census as little more than scrub, one forest policy statement dismissed such woodlands as not justifying their existence. Under a management plan entitled ‘Rehabilitation of the Hard Wood Areas’ – which was not quite what it seemed – a planting programme of conifers began in the Rowardennan oak woods by utilising existing clearings, cutting openings in the canopy and by direct underplanting. The practice continued right up to 1969, by which time some two-thirds of the native deciduous woodland in the Commission’s ownership on the east side of Loch Lomond had been converted to mixed stands.

Fig. 13.5 The exposed roots of this alder illustrate how rapidly the shoreline of Loch Lomond has eroded in recent years.

In 1973, a study of the Rowardennan oak woods was carried out jointly by the Forestry Commission and the Nature Conservancy Council (the name of the agency had changed in that same year) to examine the possibilities of reversing the coniferisation of the native hardwood areas. Time passed, and it was not until May 1989, after the adoption in 1984 of the Commission’s indigenous species-friendly broad-leaved woodland policy, that the 300 ha Loch Lomond Oakwoods Forest Nature Reserve was created with SSSI status. Within the Forest Nature Reserve, a phased programme of removing the introduced conifers began at their earliest economic stage. Forest Enterprise (the operational arm of the Forestry Commission) was to receive an environmental award in recognition of this restorative step.

Fig. 13.6 The Queen Elizabeth Forest Park successfully blends commercial forestry with recreational activities and wildlife conservation.

Since its inception, the Queen Elizabeth Forest Park (Fig. 13.6) as a multipurpose forest has developed into one of the most popular destinations in west central Scotland for outdoor recreational pursuits, attracting up to a million visitors per year.

A National Scenic Area

Aware that the face of the Scottish Highlands was undergoing change at a rapid pace with the boom in post-war forestry planting and hydro-electric schemes, the National Trust for Scotland commissioned W. H. Murray – a well-known Scottish mountaineer and writer – to undertake a survey of all the Highlands’ key scenic areas. Published in 1962, Highland Landscape enumerated and described 21 places of outstanding beauty. That Loch Lomond had for so long remained free from the most unsightly tourist developments, Murray concluded to be little short of a miracle. He was not impressed, however, with the conspicuous siting of the Hydro-Electric Board’s generating station at Inveruglas, further warning that a plan already approved to carry power from Loch Awe hydro-electric scheme across Glen Falloch would involve pylons up to 76 m tall, an intrusion on the skyline that the eye could not escape.

A more comprehensive survey of Scotland’s landscapes was carried out by the newly created Countryside Commission for Scotland (see below). Their report Scotland’s Scenic Heritage (1978) named 40 areas covering one-eighth of the land and fresh waters in both the Highlands and Lowlands requiring special planning control. Although recognised as a ‘cultural landscape’ where the imprint of man’s activities could be clearly seen, the compilers of the report concluded that Loch Lomondside lived up to its oft-sung fame. Two years later in 1980, the region was designated by the Scottish Secretary of State as a National Scenic Area. In practice, however, Lomondside’s new designation was not particularly effective as a protective mechanism and had little impact on curbing conifer afforestation or the bulldozing of unsightly hill tracks.

The Greave Report and the Countryside Commission for Scotland

Against a background of increasing private car ownership and greater mobility of the urban population, a conference looking at rural issues of the future and entitled ‘The Countryside in 1970’ (European Conservation Year) was held in 1965. In the published proceedings, attention was again drawn to the anomaly between Scotland and the rest of mainland Britain over the provision of National Parks. Study Group 9, considering countryside planning and development in Scotland under the chairmanship of Professor Robert Greave, singled out the combined Loch Lomond–Trossachs region as an obvious candidate for National Park status, not least because half of the proposed 1,108 km2 was already in public ownership. Despite the optimism felt at the time, government once more failed to live up to the expectations of proponents of National Parks for Scotland. The Greave Report did, however, successfully argue the case for the setting up of a Countryside Commission for Scotland, the necessary legislation reaching the statute book in October 1967.

The Scottish Wildlife Trust

The Scottish Wildlife Trust, a voluntary conservation body formed in 1964, established one of its very first nature reserves at Ballagan Glen in the southern Campsie Hills two years later. An ash wood with wych elm, bird cherry and hazel, the crumbling calciferous cementstones of the type formation of the Ballagan Beds exposed in the glen ensure a rich ground flora. A second Loch Lomondside reserve, Loch Ardinning (Fig. 13.7) together with the adjoining Muirhouse Muir, was gifted to the Trust in 1988.

Fig. 13.7 Loch Ardinning is one of two nature reserves in Loch Lomondside’s Lowland fringe administered by the Scottish Wildlife Trust.

The Loch Lomond Local Subject Plan

In 1977, following local government reorganisation, the District and Regional Councils covering Loch Lomondside produced a draft local plan which aimed to reconcile the increasing demands of recreation and tourism with the need to conserve and enhance the environment of the loch and its surrounds. The exceptional scenic quality of the area was emphasised, but the problems of developmental eyesores and discarded litter were also recognised. The more mountainous parts of Loch Lomondside – where particular attention was to be paid to wildlife conservation – were initially classified as ‘wilderness areas’, but on further consideration this was changed to ‘remote upland areas’, representing the most unspoilt and wild landscapes within the boundaries of the plan. Although key wildlife sites such as the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve and SSSIs were identified, the Nature Conservancy Council expressed a view that, rather than be lumped in with other issues, wildlife conservation should be treated as a subject in its own right. A water zonation scheme was proposed for the loch, to protect wildlife areas considered sensitive to disturbance. Among other conservation bodies who submitted comments on the draft plan, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds warned that the loch’s waterfowl population would be adversely affected if powerboat sports were to be allowed to go on expanding indefinitely. Such was the stand taken by the Scottish Landowners Federation, the National Farmers Union and the Department of Agriculture for Scotland in concerted opposition to the proposal to bring the agricultural and forestry industries under the control of the planning authorities, that this clause had to be dropped in favour of a voluntary code of practice. Those sceptical of a voluntary approach were equally adamant that a code of practice would do nothing to prevent a repetition of the conspicuous track bulldozed up Loch Lomondside’s eastern slopes at Cailness while discussions on controlling such potentially disfiguring activities were still taking place. The plan was finally adopted in 1986.

In a ten year review of the Loch Lomond Local Plan published in 1996, it was restated that the conservation of the characteristic ecological diversity of the whole area must be a priority objective.

The Friends of Loch Lomond and the Craigrostan Scheme

Founded in 1978, the Friends of Loch Lomond have attracted a worldwide membership dedicated to the protection of the area’s natural beauty. As such, they have been steadfast in their support for National Park status for Loch Lomondside. The Friends of Loch Lomond came to the fore when objecting to the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s plan to construct a pumped storage station and reservoir on the slopes of Ben Lomond. Named the Craigrostan Scheme, nothing before or since quite galvanised public opinion against what was perceived as yet further exploitation of Loch Lomondside’s most unspoilt land. Although some parts of the development were to be underground, there would be no hiding the construction roads, the upper storage reservoir with its water draw-down scoured sides and yet more power lines draped over open country. In order to obtain temporary storage in the loch for water released from the upper reservoir, the level of control at the River Leven barrage needed to be increased, although any rise in loch level would have aggravated the existing problem of shore erosion still further. Despite the well-publicised environmental protest, the reasons for the scheme not being pushed through at that particular time probably had more to do with an unanticipated surplus in Scotland’s electricity generating capacity following a severe decline in several of the country’s major industries.

The National Trust for Scotland and Ben Lomond

An announcement in 1982 that the Forestry Commission was to sell off 2,110 ha of the unplantable upper slopes and summit of Ben Lomond, effectively out of public ownership, was greeted with dismay and another vigorous campaign by the Friends of Loch Lomond. The Commission was accused of asset stripping by one political figure, declaring his intention of raising the matter before Parliament. The situation was only defused when Ben Lomond was handed over to the National Trust for Scotland in March 1984, a move made possible by an exceptional grant of the full purchase price from the Countryside Commission for Scotland. Needless to say, it did not escape notice that this world famous mountain had achieved the distinction of having twice been paid for with money from the public purse. Later that year, the Forestry Commission indicated to the Trust that it was also prepared to dispose of unplanted land around the upper Cailness Burn just to the north of Ben Lomond, part of which took in the North of Scotland Hydro-Electric Board’s proposed site for the Craigrostan Scheme reservoir. It was reported in the press that the Hydro-Electric Board had, in fact, submitted a bid for the area. With all the signs of another major row brewing, the Secretary of State for Scotland took the decision to block this additional sale.

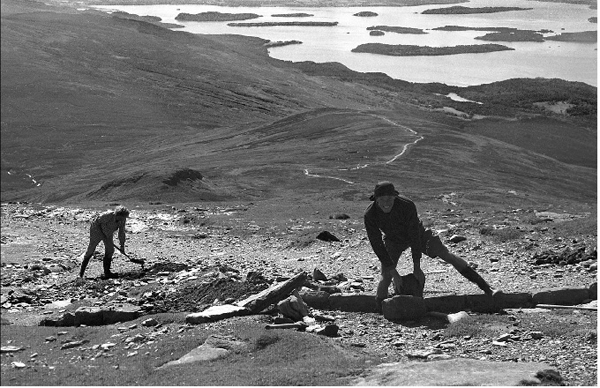

Since its acquisition of Ben Lomond, the National Trust for Scotland has put considerable resources into restoring the heavily used and badly eroded path to the summit (Fig. 13.8), protecting the existing native woodland by enclosure and initiating a restoration programme of heather moorland and other upland habitats through controlling the level of stock grazing.

Fig. 13.8 Maintaining the path to the summit of Ben Lomond is a continuous commitment for the National Trust of Scotland (Alasdair Eckersall).

The spread of private investment conifer plantations

From the early 1980s onwards, most of the new forestry developments in the region were carried out by commercial companies subsidised by planting grants (channelled through the Forestry Commission) and generous tax incentives to investors. Not unexpectedly, there was increasing public unrest over the rapid loss of open ground – particularly in the southern foothills – and the deleterious effect on Loch Lomondside’s scenic attraction through the seemingly unstoppable creeping tide of conifers, the hard-edged rectangular blocks of tightly packed trees usually following property boundaries with little consideration given to landscape design. It is to be regretted that several local wildlife sites were damaged or destroyed by private afforestation, including the floristically rich grasslands and flushes of the Highland Boundary Fault zone on Ben Bowie. Outwith local planning control, however, the pace of company afforestation only showed signs of slowing down following the withdrawal of tax concessions to forestry investors in the budget of March 1988. The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s action effectively gave a last minute reprieve to the plantable land around the headwaters of the River Endrick, which was faced with being drained and smothered in conifers.

The spectre of the ‘forbidden land’ scenario of the early 1900s was suddenly raised again following the completion of one private afforestation scheme on Loch Lomondside. A barbed wired gate and oppressive signs barred access to a popular hill area where, until the change in land use, the casual visitor had been allowed to walk freely. This return-to-the-past experience may have acted as the catalyst to a seemingly contradictory situation where members of the public who had initially expressed their disapproval at the Forestry Commission for blanketing with conifers large sections of the Kilpatrick Hills, were equally unhappy when in 1993 these same publicly owned plantations were offered for sale to the highest bidder in the private sector. Emphasising their recreational potential through the close proximity of the Kilpatricks to the Glasgow conurbation, the Friends of Loch Lomond were amongst those who registered their objection to the sale with the Secretary of State for Scotland. The Kilpatrick Hills plantations, together with a mixed wood of high scenic value beside Ross Priory on the southern shore of Loch Lomond, were taken off the market.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

With the help of grant aid from the Countryside Commission for Scotland and the Nature Conservancy Council, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds purchased 376 ha of the Inversnaid Estate in February 1986. About a third of the RSPB reserve comprises mixed deciduous woodland (Fig. 13.9), the rest hill grazings including some heather moor. To encourage natural regeneration and protect plantings of broad-leaved trees, management has been aimed at reducing the number of herbivores such as red deer and feral goats. On the higher ground, a deer-fenced enclosure under a woodlands grant scheme has been planted with Scots pine using local seed collected from the Glen Falloch pine wood, to assist in perpetuating these trees’ ancient line.

Fig. 13.9 Woodlands managed for nature conservation on the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds’ Inversnaid reserve.

The Loch Lomond Regional Park

The question of some form of distinguishing status for Loch Lomondside came back on to the agenda again after the publication of the Countryside Commission for Scotland’s report A Park System for Scotland (1974). National Parks for Scotland in the accepted sense were now firmly on the back-burner, the Commission proposing instead a tiered system headed by ‘special parks’. This alternative top-tier designation proved to be a non-runner, but the Countryside (Scotland) Act 1981 enabled the creation of Regional Parks.

Set up in 1988 with joint central government and local authority funding, the Loch Lomond Regional Park (Fig. 13.10) covered some 442 km2. The Park Authority did not, however, incorporate the word ‘Regional’ in its own title, having not given up on attaining National Park status for the area. Although the Regional Park is principally aimed at promoting outdoor recreation without losing sight of the needs of those who gain their livelihood from the land, the Park Authority also has a duty to play its part in enhancing the natural beauty and conserving the wildlife of Loch Lomondside. Visitor centres with permanent exhibitions interpreting the park’s special features have been opened at Luss and Balmaha.

Loch Lomondside as an Environmentally Sensitive Area

In May 1987, Loch Lomondside was one of the first two regions in Scotland to be designated an Environmentally Sensitive Area. Under the provisions of the Agricultural Act 1986, land occupiers who volunteer to enter into a management agreement based on a farm conservation plan would be offered incentive payments to undertake environmentally sensitive practices. Objectives within the designated area include protecting the landscape from badly designed farm buildings and hill tracks, restoring stone walls and hedges to maintain the traditional appearance of the countryside, encourage natural regeneration of broad-leaved woodland by enclosure and protecting heather moor and species-rich grassland from overgrazing.

Fig. 13.10 The Loch Lomond Regional Park was the first of its kind in Scotland.

The Mountain Areas of Scotland Report

The Mountain Areas of Scotland Report (1990) was the response of the Countryside Commission for Scotland to an invitation from the Scottish Minister for Home Affairs and the Environment to study management arrangements for the country’s popular mountain areas. Scenery and wildlife were to be included in their remit. The Commission concluded in their report that Loch Lomondside was a prime candidate for special status, the preferred area – which included both the Argyll and Queen Elizabeth Forest Parks – particularly important to the people of Scotland’s central belt as their most readily accessible hill and loch country. This time the Commission was less hesitant in the choice of top-tier designation, proposing National Park status with an independent administrative board, planning control (which would include farming and forestry) and a high proportion of the total funding of the park to be met by central government. In this, the Commission reflected the aspirations of all proponents of National Parks for Scotland.

Predictably, publication of the report recommending National Parks for Scotland immediately marshalled the now familiar and well-organised landowning opposition to the proposal. Instead of the hoped-for Government support for National Parks, what followed was the watered-down Natural Heritage (Scotland) Act 1991. This gave the Secretary of State for Scotland the power to designate Natural Heritage Areas founded on the voluntary principle and not perceived as requiring their own independent administrative body. With the exception of the anti-National Park lobby, who immediately seized upon the designation and called for Loch Lomondside to become a Natural Heritage Area, the open-to-abuse voluntary code of practice in countryside protection was greeted with little enthusiasm and to date no National Heritage Areas have been established in Scotland.

This was to be the last opportunity for the Countryside Commission for Scotland to express their support for Scottish National Parks with effective statutory protection and maximum financial backing from central government, for in April 1992 the Commission and the Scottish arm of the Nature Conservancy Council were merged to form a single agency, Scottish Natural Heritage.

The Hutchison Report

In 1991, as a follow-up to The Mountain Areas of Scotland Report, the Secretary of State for Scotland announced the setting up of a working party under the chairmanship of Sir Peter Hutchison to address more precisely the management issues connected with visitor trends and their effect on the natural heritage of Loch Lomondside and the Trossachs area. In their report The Management of Loch Lomond and the Trossachs published in 1993, the working party concluded that improvements to communications together with greater disposable wealth had combined to threaten the very features that drew people to Loch Lomondside in the first place; and that there was a real need for urgent action to safeguard the precious but inherently fragile qualities of the area. They accordingly recommended that care of the natural and cultural heritage of the area should be adopted as the fundamental principle in any future plan.

Despite the thoroughness of the Hutchison Report, an air of disillusionment quickly surfaced when it became clear that right from the outset, the working party had been precluded from considering any kind of independent administration board such as those of the National Parks in the Lake and Peak Districts of England, but only what might be achieved under the legislative framework already in place for Scotland. This was despite public opinion polls – including one undertaken by the Scottish Office in 1992 – which indicated that up to 90 per cent of Scots favoured the introduction of National Parks on lines somewhat similar to those elsewhere in the United Kingdom.

Advocates for National Park status for the region were by now well used to such knock-backs, although this time they sensed a coming change in the flow of the tide. One-day conferences held on Loch Lomondside, which were organised by the Member of Parliament for Dumbarton, continued to keep the issue of National Parks for Scotland to the forefront of public and media attention.

The Ben Lomond National Memorial Park

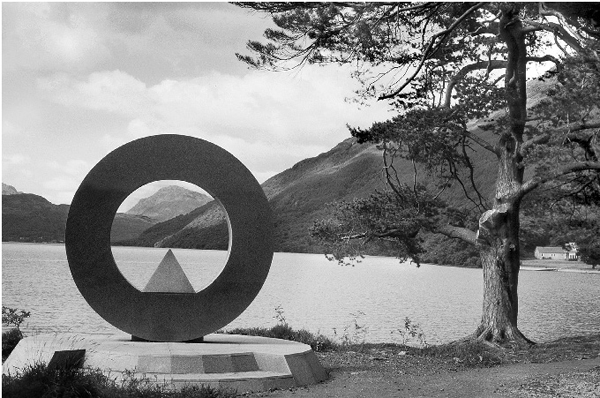

After lying dormant for the best part of half a century, the landscape conservation objective of the National Land Fund – under which the Rowardennan Estate was first purchased for the nation – was suddenly raised again in 1995, when attention focused on Forest Enterprise’s design plan for restocking the Rowardennan plantations as the first generation of planted conifers approached the stage of harvesting. Although the Friends of Loch Lomond applauded Forest Enterprise’s initiative in oak wood restoration, they strongly objected to that part of the plan under which the replanting of non-native Sitka spruce would be little reduced elsewhere. Following a brief skirmish in the press between the Friends and Forest Enterprise, events moved swiftly, culminating on 3 June 1996 with the signing of a concordat between the Secretary of State for Scotland, the Forestry Commission and the National Trust for Scotland for the long-delayed dedication of the area in remembrance of the thousands of Scots who died in military service during the Second World War. Forest Enterprise produced an innovative long-term plan to replace the blocks of conifers with well-designed mixed stands of native trees, planted and harvested in much smaller lots and at different times under what is termed ‘continuous cover forestry’. Apart from the scenic improvement, the age/species mixed deciduous stands will encourage and sustain a far greater variety of wildlife than the even-aged, closely planted conifers. The plan not only attracted a prestigious forest management award, but with the land to be held inalienably as a living monument to the war dead, in theory at least it removed the threat of a pumped storage hydro-electric scheme being constructed on the site. Fittingly, the Ben Lomond National Memorial Park was formally opened by the Secretary of State on Remembrance Day 1997 (Fig. 13.11).

Fig. 13.11 The Ben Lomond National Memorial Park monument symbolises the hopes of all those who wish to see this scenic area remain unspoiled in perpetuity.

The Millennium Forest for Scotland

In August 1996 a trust company representing the Royal Scottish Forestry Society acquired 1,214 ha of hill sheep ground at Cashell, formerly the southern-most part of the Rowardennan Estate originally purchased for the nation through the National Land Fund. As part of the Millennium Forest for Scotland project, the trust company’s intention is to return a large part of the land to indigenous woodland, using principally oak on the lower ground, with Scots pine and birch ascending to ericaceous and other shrubs on the upper slopes. Within a year of the scheme’s launch and extensive deer fencing being erected, some 100,000 native trees had been planted. Further north at Craigrostan between Cailness and Inversnaid, the Jensen Foundation of Denmark had acquired a large stand of oak in 1987. These former coppice woodlands were incorporated into the Millennium Forest for Scotland in 1997, work carried out including enclosure fencing, rhododendron removal and individual protection of naturally occurring seedlings by the use of tree tubes. In the same year, the National Trust for Scotland began extending its existing woodland enclosures on Ben Lomond under the Millennium scheme.

Together with the current woodland protection and replanting initiatives of Forest Enterprise and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the total extent of woodland cover along the lochside’s eastern slopes seems set to become the showpiece of forest restoration in Scotland. Modern day planting may never replace the genetic strains of native tree species that have been lost by man’s activities over thousands of years, but with sympathetic management – which must allow for a percentage of the trees to mature, die naturally and rot down – Loch Lomondside’s ‘New Forest’ should in time assume many of the characteristics of the original wildwood.

The Natura 2000 Network

Under the European Community Birds and Habitats/Species Directives, Britain accepted the responsibility to designate Special Protection Areas for birds considered rare or vulnerable and Special Areas of Conservation to support rare and endangered habitats, together with their associated species of plants and animals (other than birds). Both protection and conservation areas go under the umbrella of the Natura 2000 Network.

Sites proposed for Loch Lomondside take in the Endrick Marshes for wintering Greenland whitefronted geese and four of the largest wooded islands in the central basin of the loch for capercaillie as a combined Special Protection Area. Special Conservation Areas take in the River Endrick from its mouth to the Loup of Fintry (particularly for spawning river lampreys and Atlantic salmon) and a large proportion of the western acidic oak woodland on the islands and around the loch.

A look to the future

The ink was barely dry to this short history of the conservation movement in the Loch Lomond area when the new parliament in Edinburgh passed an enabling bill to establish National Parks in Scotland, with Loch Lomondside and the Trossachs chosen to be the very first. After a litany of missed opportunities and one study report after another consigned to the back of the cupboard to gather dust, Scotland will no longer stand alone as the only country in Europe not having this internationally recognised top-tier designation for its finest scenic areas. There are many issues that will have to be resolved before the proposals contained within the bill are translated into reality, but for those who have held firm for National Park status for Loch Lomondside their long struggle for nature’s place is almost at an end.

How has the region fared in the 70 years since the Rowardennan Estate together with Ben Lomond was first unsuccessfully offered to the country as a National Park? In his excellent book Loch Lomond, published in 1931, Henry Lamond made the following appeal: ‘My modest plea is that no cottager within his limited domain, that no landed proprietor within his estate, and that no Local Authority within its administration area, should countenance or tolerate anything that may result in the ultimate degradation of Loch Lomond’. Since those words were written, Loch Lomondside has witnessed the intensification of agriculture practices, an unprecedented spread of plantation-style conifers and loss of heather moor, further water storage provision including a massive hydro-electric scheme and harnessing as a major water supply the loch itself. To this should be added the vastly increased traffic that has necessitated road realignment and widening on a scale never before experienced, together with the ongoing upgrading of tourist and other leisure facilities. Resulting from the combined effect of all these competing claims for land and water, it cannot be denied that Loch Lomondside has become a little frayed around the edges, its scenic beauty and wild places all to often having to take second place to developmental interests. Overall, however, apart from the excessive disturbance on the loch created by the recent free-for-all in fast powerboat sports – which as a keen fisherman he would have found totally unacceptable – it is unlikely that Henry Lammond would be too disappointed. Despite all the uses and abuses, the Bonny Banks have somehow managed to retain a semblance of balance between its heritage of nature and the people’s needs. In a rapidly changing world, where the importance of conserving a representative variety of native flora and fauna in every region is increasingly recognised, Loch Lomondside is acknowledged as one of the finest Scottish pearls in the United Kingdom’s biodiversity crown. That it should remain so, as the area enters the new millennium with a new future as part of Scotland’s first National Park, is in our own hands.