CHAPTER TWO:

LOUISBOURG UNDER SIEGE

The French and English were still battling for supremacy on the east coast almost 50 years later. The French had Louisbourg but the English had their New Englanders. The latter were just as determined to remove the French presence from the Atlantic coast as D’Iberville had once been to remove the English.

On the cloudy, moonless night of May 10, 1744, the English found their opportunity. Darkness had fallen early and as it did a motley collection of fishing boats, bateaux, and small merchant ships slipped their moorings outside of Canso, Nova Scotia. On board were a ragtag collection of would-be soldiers: students, clerks, and farm boys seeking adventure; and adventurers seeking booty. Few of the men had any military experience and though there were cannons on board, there were no trained gunners to man them. Fuelled by rivalry, revenge, and religion, the men headed toward Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, to capture the fortress and force the French Catholics out of the colonies.

Many people, including most of the colonists who had volunteered, considered the invasion a fool’s errand. The fort was widely considered to be impenetrable. In a letter to his brother, the venerable Ben Franklin urged caution and warned that, “fortified towns are hard nuts to crack; and your teeth are not been accustomed to it … But some seem to think forts are easy taken as snuff.” 1

Louisbourg was the Gibraltar of the West, an impenetrable bastion designed with the lofty goal of ensuring the survival of the French Empire in the Americas.

The Treaty of Utrecht had stripped French North America bare. They had been forced to give up most of their prized possessions: Acadia, Rupert’s Land, and Newfoundland. All that remained were Île-Saint Jean (Prince Edward Island) and Île Royale (Cape Breton Island), a tiny island of rock and bog upon which France’s future in North America would rest. Upon that rock they began construction of a massive fortress, the largest and most indestructible in North America. They called the fortress Louisbourg, after their king.

The fortress stood guard over the St. Lawrence and controlled access to France’s inland possessions, including Quebec City. The fortress also protected the French fishing boats that vied with the English for access to valuable fish stocks, and the numerous French privateers who preyed on vulnerable English colonial merchant ships. Unfortunately, Louisbourg served as a beacon, a constant reminder to the New Englanders and other English colonials of the French presence in North America. They viewed its creation with increasing irritation and a growing conviction that their duty to Britain lay in the destruction of Louisbourg, and of the French influence in North America.

It would not be an easy task. The fortress had cost the French treasury over 30 million livres2 to build and its upkeep and repair were a constant strain, but by 1745 it loomed menacingly over the gateway to the St. Lawrence. Lying in front of the fortress was a deep harbour, protected on the south side by reefs and an island battery that functioned more like an independent fort. Only three boats could land at the single, small beach, and most of the time the surf prevented even that. To the northwest the French built another battery, the Royal Battery, with twin swivel guns mounted in its towers that could swing between the harbour and the fort. Twenty-eight more 42-pound guns were aimed directly at the harbour entrance. Larger ships were forced to enter the bay via a narrow, 152-metre wide channel, between the Island and Royal Batteries and under the watchful eyes of the battery gunners. At the edge of the island, Canada’s first lighthouse provided direction along the craggy shore to the hundreds of boats that visited the fort every year. There were natural protections as well: the swells outside the harbour were unpredictable and the area was notable for the thick, impenetrable fogs that frequently blanketed the landscape.

The fortress itself was impressive. Outer walls that were 1.5 metres thick stretched for almost five kilometres around the site, enclosing just over 100 acres.

The fortress walls were nearly 11 metres thick and nine metres high. There were places for 148 cannon and a 25 metre wide moat encircled the entire fort. The defences to the rear of the fort were less intimidating, but the French engineers who built it were not anticipating a land invasion. Besides, several kilometres of thick swamp stretched across the land beyond the fort, swamp the engineers considered to be impassable.

The site was near perfect for defence.

The New Englanders watched as the fort grew in size and influence. They also saw the ships leaving the busy harbour of Louisburg bound for France, their holds filled with valuable cargoes of dried, salted cod, and returning loaded with wine, foodstuffs, and finery. By 1744, they felt they had seen enough. They began to make plans to invade and force the French Canadians from the shores of North America for good. One of the most ardent lobbyists for the invasion was Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts. Like many governors of the period, he was also a merchant and felt the losses inflicted by competing French merchants and French privateers.

There had been whisperings of an invasion for months. American merchants and politicians were lobbying hard, trying to convince the British and colonial governments to support their efforts to evict the French. But before any invasion could take place, the War of the Austrian Succession began, pitting France against Great Britain once more. By stroke of luck, the French Canadians received word of the war a full three weeks before their New England counterparts. They saw this as their opportunity to restore French North America to its former glory.

The French soldiers attacked a small New England fishing fort at Canso, captured it, and took several captives back to Louisbourg. Then they turned their attention to Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, with the intention of liberating Acadia from the British. But the French were outmanned and outgunned and the Acadians showed little enthusiasm for the cause. After a half-hearted attack, the French withdrew back to Louisburg.

The New Englanders were still hesitant to attack Louisburg. A secret ballot held in both the senate and the legislature denied the governor the power to launch an invasion. The fortress, their experts argued, was too strong, too impenetrable; the invasion of Canso was regrettable, but in the end it was not worth a war. But the Puritan public, already irritated by the close and competing presence of French speaking papists, forced another vote and finally the invasion was approved. Governor Shirley wrote to his neighbours requesting their support. Massachusetts sent over 3,000 men, New Hampshire and Connecticut sent 500 each.

The force gathered at Canso and waited impatiently for the ice to thaw. While they waited the officers attempted to drill their men, and preachers shouted outdoor sermons lauding the soldier’s courage and the justness of the mission. Sometimes the cacophony made it difficult to distinguish between preacher and officer. As one diarist put it, “Severall sorts of Busnesses [sic] was a-Going on: Sum a-Exercising, Sum a-Hearing o’ the Preaching.”3

By the time the New Englanders began to gather at Canso, Louisburg was already eroding from within. Because they were caught up in battles closer to home, France had failed to adequately supply or repair the fort. In December, the small force of regular soldiers at the fort, a mere 560 men, mutinied after discovering that government officials were cheating them out of their rations. The mutiny was diffused, but the cheating continued and government and military officials regarded each other with growing resentment. The only other defenders were the militia, which comprised the largest part of Louisburg’s fighting force and included nearly every Cape Bretoner who could stand and hold a musket. There were young boys and old men, nearly 1,300 in all.

Despite the clear rumblings that warned of an imminent invasion, little was being done within the fort to prepare. Councils of war were called and there was a lot of discussion, but no action was taken. Instead, they waited for reinforcements. France had promised an additional 2,000 troops to launch a full-scale invasion of Acadia. Rumours of the imminent arrival of a Quebec guerrilla fighter named Marin, along with a small force of First Nation and Quebec fighters, buoyed the residents of Louisbourg. It could only be a matter of time before the French soldiers arrived. Unfortunately for Louisbourg, neither Marin nor the promised French reinforcements arrived.

Within the walls of the fort, life continued in much the same way it always had. The civilian population, which easily equalled that of the military, continued to work, trade, and live their lives. Their confidence returned as the threat of invasion seemed to fade. The fortress was, after all, impenetrable.

A few worried voices did reach out to France, chiefly that of an anonymous inhabitant of Louisbourg who warned of the imminent invasion and the ill-equipped fort that would attempt to repel it. The warning went unheeded. The expected reinforcements from France failed to arrive and the New Englanders launched their attack. Luck, wrote the habitant, was clearly on the side of the New Englanders. Even the weather co-operated. “The English … seemed to have enlisted heaven in their interests,” he wrote. “So long as the expedition lasted, they enjoyed the most beautiful weather in the world.”4 The wild winds that usually whipped the Cape Breton coastline abated, the fog that enshrouded it lifted. On the morning of March 14, the habitant watched in horror as host of British American ships entered the bay, coming from all directions: Acadia, Boston, Placentia…. The invasion had begun.

Although the habitant, locked securely in the fortress of Louisbourg, could not have known it, two French ships did eventually try to come to the rescue of Louisbourg. The first, the Renommée, had been sent in January and was forced to wait until the ice had broken up before it could reach the area. Finally, at the end of March it sailed by Canso, where it caught the attention of the English who pursued the ship until its captain finally gave up and returned to France. A second French ship, the Vigilant was dispatched loaded with provisions and carrying a full contingent of reinforcements, some 600 men. The Vigilant sailed into Louisbourg harbour on May 20 and again the British gave chase. A fierce battle raged through the day and night, and finally the French ship struck its colours. No more reinforcements would be sent; Louisbourg was on its own.

On board one of the English ships was a merchant named William Pepperell, who had been handpicked by Governor Shirley to lead the expedition. Pepperell, like most of the Massachusetts militia, had no military experience, but he was well respected, sensible, and committed to the cause. The mission itself had begun to take on almost a crusade-like atmosphere as religious leaders in the colonies whipped up anti-Catholic and anti-French fervour. One of the chief advocates of these sentiments was the evangelical leader George Whitfield. But despite his zealous support for the cause in his pulpit, Whitfield had warned his friend Pepperell that he would be envied if he succeeded and abused if he failed.5 Both men believed the latter was the far likelier outcome.

Carefully hiding any misgivings he may have had, Pepperell sailed his flotilla into Gabarus Bay, alongside four ships commanded by the British Commodore Peter Warren. Almost immediately the bells of Louisbourg began to peel out a warning and a canon fired a single shot. Citizens from the surrounding countryside scurried to safety behind the fortress’ great walls. Also inside, the anonymous habitant decried the ill-conceived French raid on Canso. “The English would perhaps not have troubled us if we had not first affronted them,”6 he wrote. The habitant appeared to have an intimate knowledge of the fortress and had reservations about its ability to withstand an assault. In his letter he refers to several unrepaired breaches in the walls of the Royal Battery. In his official report the acting governor of Louisbourg admitted that many outer defences had been destroyed in advance of a longer term plan to rebuild them.7

Unfortunately for Louisbourg, Governor Shirley was also very familiar with the fortress’s flaws. The prisoners taken at Canso had returned from Louisbourg with a detailed description of the fort, and the information they lacked was supplied by the many merchants who had carried on an illicit and very profitable trade with the fort for years. Shirley gathered this information and drafted a complex plan of attack for Pepperell to follow. The plan was an interesting one. It called for Pepperell to make his landing at night. Once on land, the force would separate into four parts. The first two would advance toward the walls in complete silence. The third would approach the Royal Battery and also wait in complete silence for a prearranged signal. The final silent group would approach the fort from the beach, climb the walls, and capture the governor. Shirley expected all of that to be accomplished undetected and in unfamiliar territory.

Pepperell might have lacked military experience but he certainly recognized a ludicrous military plan when he heard one. After a quick feint that drew the French in another direction, he landed his troops several kilometres to the southwest of the fort in the daylight, setup camp, and dispatched troops to do some reconnaissance. The troops raided nearby farms and then discovered and set fire to the naval storehouses. Then their commander, William Vaughn, made camp for the night, allowing his men to scatter and find their own way back. By morning there were only 13 men remaining. Rather than risk running into a French advance force, he decided to return to Pepperell and the main camp. On their way they passed to the rear of the Royal Battery. No smoke rose from fires, no guards walked the rampart, only silence called to them from behind the high walls. Vaughn and his 13 soldiers crept closer, but there was still no sign of life from within the battery. They bribed a local Mi’kmaq who, feigning drunkenness, stumbled up to the gate of the fort. He found the entire battery deserted. The French soldiers, shaken by the fires and the blinding smoke of the burning naval storehouses, had slipped away in the night.

Vaughn marched his small band of men into the fort and one of the youngest shimmied up the flag pole, tore down the French blue, and replaced it with his own red jacket. Vaughn then penned a quick letter to Pepperell requesting a proper flag and few additional men to hold the battery. They also discovered that the French had made a fateful mistake in their hasty abandoning of the Royal Battery.

They had failed to spike the guns or destroy the stores, leaving the invaders with easy access to arms and munitions, both of which they immediately turned on Louisbourg with devastating effect. Within the fortress walls, the booming guns of the Royal Battery wreaked havoc as houses collapsed and the inhabitants ran in terror into the streets.

Pepperell then set his sights on Louisbourg itself. Within sight of his encampment lay the perfect venue from which to launch an attack on the fortress city: the high hills that surrounded its walls. But between Pepperell and the hills lay exposure to Louisbourg’s formidable guns and a deep, murky bog that stretched for several kilometres. The first attempt made by the army to cross it ended disastrously with the colonists’ guns lost in the thick mud. Finally, one of the soldiers designed a gun-sleigh that could be pulled across the marsh. Up to 200 men manned each sleigh, making slow, painful progress across the wet bog. Orders from their superiors had them travelling only at night or under cover of one of Louisbourg’s notorious fogs. Experience eventually taught them to take a different route every time, since crossing the bog twice in the same location turned the ground into an impassable soup. Each morning, as the sun rose over the ocean, the soldiers, wet, cold, and exhausted, would take refuge behind a boulder or tree and try to sleep as the French shells landed all around them. Then, as darkness fell, they would pick up their ropes and continue their trek toward the hills.

Pirates and Privateers

Pirate attacks were a frequent, and occasionally fatal, annoyance during the War of 1812. In fact, Canadian pirates, sanctioned by local governments and the British navy, helped win the battle for the Atlantic coast, capturing dozens of American ships and winning a fortune in prizes for their owners.

But the War of 1812 was not the only time that pirates sailed Canadian waters. Eighteenth century French privateers regularly harried the Massachusetts coast from their home port at Fort Louisbourg. These pirates were also a key participant in the defence of Port Royal and Louisbourg from the English who would have taken it. Ca-nadian privateers were also active throughout the Napoleonic Wars. When the French disrupted Nova Scotia’s profitable trade with the West Indies, Canadian pirates re-taliated by attacking French and Spanish merchant ships. That venture proved even more profitable than the original trade with the West Indies had been. The Rover was the most infamous of the Canadian pirate ships of that time. It quickly established a reputation as a ship with a crew as ruthless and they were undefeatable, even against incredible odds. Working alone, the crew of the Rover once attacked a convoy of seven merchant ships, seizing three of them; in another instance it engaged three Spanish warships and defeated all of them.

With its numerous isolated settlements and expansive coastline, Canada was also a favourite hunting ground for pirates from other nations, particularly in the earliest days. One of the first pirate attacks occurred in 1582 when a pair of English pirates raided Portuguese and Spanish fishermen on the Avalon Peninsula. In 1668, Dutch privateers twice raided the Avalon, burning ships, houses, and chattel in the harbour and briefly taking St. John’s. But when they returned in 1673 the people of St. Johns were ready for them. They laid a heavy chain across the harbour that caught and held the Dutch ships. Before they could disengage themselves, the men of St. John’s sent a small flotilla of fire ships toward the Dutch pirates, burning several of them to the waterline and forcing the rest back out into the Atlantic.

By May 4, the colonials had set up a battery on Green Hill, less than 1,500 metres from Louisbourg. They had also managed to turn several of the guns from the abandoned Royal Battery back onto Louisbourg. The soldiers continued to roll the guns toward the hills, setting up batteries and not slowing until they set up their final advance battery less than 225 metres from the west gate of Louisbourg. It seemed, at least for a few moments, that Louisbourg might collapse easily and quickly. Within Louisbourg itself, the prospects seemed bleak. Soldiers and citizens alike took refuge when the shelling was at its most intense and crept out during the occasionally lightening of the barrage to repair the damage. It was a futile task. The shells fell almost continuously and building after building was destroyed. By the time siege ended just one house remained standing.8 Provisions were scarce. For days no one had ventured from the fortress and no relief ships had found their way in. No reinforcements arrived from Annapolis or France. The men, women, and children of Louisbourg were on their own. Food was scarce and strictly rationed with the choices bits saved for the officers and government officials. From outside the walls they heard the taunts of the British soldiers only metres from their front gate. The defiant return taunts of their own soldiers did little to buoy their spirits. No action was taken; no soldiers marched to meet the enemy. There were rumours that the French governor had received a demand for surrender from the English and that he had turned it down, there were countless councils of war but nothing seemed to happen. Instead, they waited, hungry, exhausted, and terrified. Whether they waited for reinforcements or rescue no one was really certain. The only thing they could be sure of was that the colonists waited outside their doorstep and on nearly every hill surrounding the city that was crumbling around them.

There was a solution, but the French commanders did not seem to see it. The colonial flanks were clearly exposed and unprotected. The French just had to send out troops to attack the isolated batteries, but the commanders feared the tenuous hold they had on their men after the recent mutiny. The habitant lamented that the commanders did not dare send out their troops to challenge the English for fear that the unhappy, recent mutineers might join the enemy.9

The New Englanders had problems of their own. The eager, inexperienced gunners would frequently overload their canons, causing fatal explosions. Insubordination was also rampant, as was drunkenness. The men frequently ignored orders and alcohol inhibited their ability to fight and occasionally resulted in their not showing up to the fight at all.

Warren and the British Navy hovered just outside the harbour, held back by the guns of the Island Battery. They were eager to join the fight and Warren constantly pressed Pepperell to take action against the battery. But while the colonials were able to secure the lighthouse, the battery remained defiant. The first four plans to attack were abandoned. On the first actual try, most of the 800 colonial soldiers came to the battle drunk and the officer in charge of the operation failed to show up at all. In a second attempt, the colonials crept up to the battery under cover of the area’s notorious fog. Once one third of the men had reached the beach undetected, a few inebriated soldiers called out three cheers for their success. The French immediately opened fire and for the next several hours, chaos reigned.

When the smoke and fog finally cleared, over 60 colonials lay dead and several hundred had been taken prisoner. The Island Battery still belonged to the French.

Warren still pressed to join the fight and Pepperell knew that success in Louisbourg depended upon his capture of the Island Battery. A second attempt was merely a matter of time and careful planning. Pepperell salvaged a number of heavy guns that had been sunk by the French just beyond the lighthouse and ordered his men to construct a battery near the lighthouse to house them. The lighthouse offered an unmistakeable advantage — its elevation was much higher than that of the Island Battery and, once completed, the salvaged guns could be pointed directly into the small fort. They completed work on the fort on June 10, and almost immediately opened fire on the Island Battery. For two days they kept up a steady barrage that ended with many of the French fleeing into the surf and taking their chances swimming to the fortress. By nightfall on the twelfth, the Island Battery was in colonial hands. Almost immediately the British sailed into the harbour eager to join the fight.

The citizens of Louisbourg had seen enough. Their soldiers were exhausted, as was their supply of gunpowder. Within days the Circular Battery had been reduced to ruins and the west wall completely destroyed. The colonials were in control of the West Battery itself and had turned its terrifying guns down into the city they had been designed to protect. The British were massing their fleet in front of the city. The citizens petitioned the government to end the siege. After 45 days of relentless shelling, the siege was finally lifted. The acting governor, Duchambon, initiated a surrender in which the French would be allowed to march out in their colours and the citizens within Louisbourg would be granted safe passage to France along with all of their property.

The colonial soldiers, many of whom had joined in hopes of reward, were angry that the loot they had hoped for would be denied to them. They would be angrier still when they finally realized the consequences of “the Greatest conquest, that Ever was Gain’d by New England.”10 But in the meantime, cities in both the colonies and Great Britain celebrated the victory over Louisbourg with speeches, picnics, and fireworks. In London, the Tower guns were set off and more fireworks illuminated the skies. Warren, Pepperell, and Governor Shirley all gained tremendous rewards and accolades. Warren was made a rear admiral, Pepperell received a baronetcy, and Shirley received the lucrative right to raise regiments. But not everyone found their riches in the invasion. William Vaughn, the erstwhile captain who had so buoyed the invasion with his taking of the Royal Battery, travelled to London hoping for reward. He received no recognition and instead contracted smallpox and died in the winter of 1746. The rest of the men received no riches and only the momentary gratitude of their fellow New Englanders. Two thousand of them also received notice that they were expected to continue their occupation of Louisbourg until they could be relieved by a force on its way from Gibraltar. The force failed to arrive. Pepperell wrote to his wife,

We have not as yet any answer to our express’s from England, and it being uncertain whether I shall return this winter, although it is the earnest desire of my soul to be with you and my dear family, I desire to be made willing to submit to him that rules and governs all things well; as to leave this place without liberty. I don’t think I can on any account.11

Conditions within the fort were nothing short of brutal. The men lived in squalid, filthy conditions in the ruins of the fort. The sickness that had plagued the troops over the cool, wet summer worsened as the weather got colder. Once winter had closed the fort off from any new provisions or relief the sickness worsened.

Between November and January, 561 English soldiers were buried at Louisbourg, many beneath the floorboards when the ground became too frozen for the survivors to dig graves.12 That number is staggering compared to the total loss of 130 men during the siege: 100 to gunfire and another 30 to disease. By February, Pepperell commanded just 1,000 able-bodied men; the other 1,000 had been felled by sickness or death. The British governor wrote of his time in Louisbourg, “I have struggled hard to weather the winter, which I’ve done thank God, tho was not above three times out of my room for five months … I am convinced I shou’d not live out another winter in Louisbourg.”13 To further compound their troubles, the men received minimal pay and found their protests falling on deaf ears. In one dramatic episode, a group of New Englanders marched to the parade ground without their officers and tossed their weapons down. A British Navy officer, who had witnessed both the conditions at Louisbourg and the protest, remarked that he had always thought the New England men to be cowards but he thought that if they had a pickaxe and a spade they would dig their way to hell and storm it.14

In March the promised relief finally arrived and the surviving colonists were allowed to return to their families. A small group of them took a souvenir with them: a large iron cross from the cathedral at Louisbourg. Eventually finding its way to Harvard, the Louisbourg Cross remained at the university for nearly 250 years until they finally agreed to permanently loan it to Canada in 1995.

But in 1746 the battle was still going on, at least in the eyes of the French. On the heels of the British reinforcements a flotilla of French warships had also headed toward Gabarus Bay, intent on retaking the fort and redressing the humiliations suffered at Louisbourg. But luck and weather once again favoured the English colonists. The French fleet was plagued by illness, beset by storms, and harried by the English Navy until it finally gave up and abandoned its mission to retake Louisbourg. The English who were in command of the fort were elated, but their joy soon turned to disgust when news reached them that during the negotiations of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle the British had traded Louisbourg back to the French in return for the small fort of Madras in India. Everything the colonists had fought for had been abandoned; the French commanded the mighty fort of Louisbourg once more.

The French were not able to enjoy the fort for long. By 1757 they were back at war with the British, and both the Americans and the British had once again set their sights on Louisbourg. They started slow; first isolating Louisbourg by confining the first fleet of reinforcements sent to the city and then by defeating a second fleet sent out to rescue the first. A third fleet finally made its way to the island but its commander, worried about a possible invasion, decided to lead his ships to the relative safety of Quebec. His concerns were justified. The French had made some important improvements to the fortress. They were no longer exposed along the swampy east; instead they were protected by lines of guns and trenches, fronted by a further defence called an abatis, felled trees that were sharpened and pointed towards the advancing enemy. Despite the French having strengthened the fortress it was still a tempting target because it controlled access to Quebec and the rest of French Canada.

With Quebec City as the final target, the British planned two major campaigns. The first, involving over 15,000 men, was launched against Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain, while Major-General Jeffrey Amherst led a 12,000 man force toward Louisbourg. Among the officers that Amherst selected to launch the attack on Louisbourg was a young James Wolfe, who would go on to lead the invasion of Quebec City and end French hegemony in North America forever. While the British locked down all of the ports from Nova Scotia to South Carolina, in order to keep the invasion secret, Amherst gathered his troops in the newly built Fort George in Halifax. Within weeks they were joined by nearly 14,000 sailors and marines. Within Louisbourg, a force of barely 7,500, and 4,000 civilians, waited nervously for the inevitable invasion.15

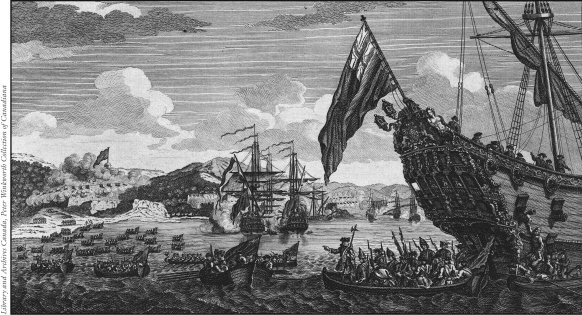

As dawn broke on June 1, 1758, the shocked Louisbourg sentries finally spotted the first sails of the massive invasion force anchored in Gabarus Bay. Rough seas kept them at anchor but the swells calmed and in the early hours of June 8 the entire fleet doused their lights while 2,000 soldiers slipped into the small bateaux that would carry them to shore. They bobbed in the water, waiting for the signal that would launch a three-pronged attack on three French beaches.

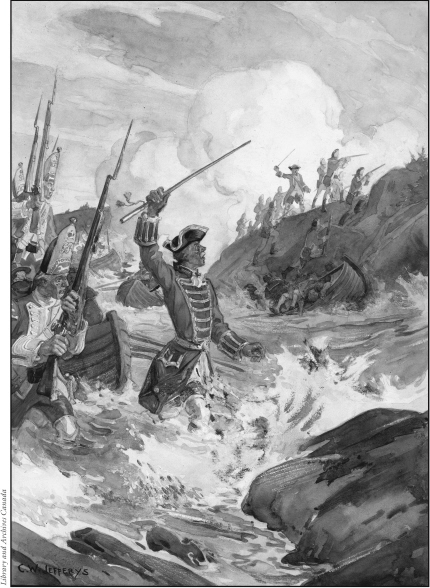

At 4:00 a.m., the ships began to fire on Louisbourg and the fortress answered with the steady beat of drums sounding the générale — the call to arms. Most of the French forces turned a steady, terrifying barrage against the tiny boats. Several boats overturned and the soldiers, weighted down by their heavy uniforms and packs, sank to the bottom of the bay. As a horrified solider looked on, “One boat in which were Twenty Grenadiers and an officer was stove, and Every one Drowned.”16 Standing at the bow of his boat, his red cape flapping in the wind, General Wolfe made a tempting target. But the French held their fire until the boats were well within musket range, and then let loose a furious barrage that left Wolfe desperately waving the accompanying boats back with his cane. They attempted to turn around amidst heavy fire from the French and rough waves that pushed them back toward the shore.

It seemed that the massive invasion, so carefully planned, was going to end in unmitigated disaster. But then, as occasionally happens in war, fate intervened and saved the day for the British and colonials. Officers aboard three of the boats spied a rocky outcropping beyond the range of the French guns and turned toward it. Wolfe immediately ordered the ships nearest him to follow and they pulled their boats onto shore beyond the view of the French. The French Governor Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour was stunned to learn that the British and Americans had made land. Instead of launching a counterattack, he elected to pull back. He ordered the Royal Battery destroyed and abandoned. A day later he ordered the Lighthouse Battery destroyed and then withdrew his men into the fortress.

Wolfe Walking Ashore Through the Surf at Louisbourg.

Wolfe barely missed a beat. He marched his almost 2,000 strong army around the bay with an eye to taking and rebuilding both the Lighthouse and Royal Batteries so that they could be used against Louisbourg. In the meantime, Amherst kept his own army busy building a road through the sand, bog, and marsh in preparation for an attack by land. In a replay of the 1745 attack, hundreds of men were put to work pulling the massive guns into position. On June 18, the soldiers were startled to hear the sounds of a naval battle occurring within Gabarus Bay. They did not know it then, but de Drucour had attempted to smuggle his wife and several other women out of Louisbourg to the safety of Quebec. Madame de Drucour and her companions were taken from the defeated French ship and returned with honour and consideration to her husband at Louisbourg. Despite the courtesy of the British, for the remainder of the siege Madame de Drucour climbed the fortress ramparts daily to fire three canon shots in honour of the king of France. Amherst was so impressed with the lady’s courage that he sent her a letter and a gift of two pineapples with several messages and letters from captured Frenchmen. Another flag of truce appeared and a basket of wine was delivered to Amherst with the compliments of the governor and his wife. As soon as the wine was delivered the canons roared to life on both sides. Courtesy and compliments aside, there was still a war to be won.

The defence of Louisbourg must have seemed hopeless even to the most optimistic of the French troops. But de Drucour refused to surrender, knowing that the longer he held out the less likely it was that the British fleet would move on to Quebec. By the end of June the walls of Louisbourg were crumbling and the city had no defences beyond what was left of them. Then, a British bomb exploded in the magazine on board one of the French ships. As the magazine exploded, sparking a horrific fire, the British continued to pound the ship with cannons and the fire spread to two nearby ships. French soldiers and sailors leapt into the sea, exchanging a fiery death for a watery grave.

The Expedition Against Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, 1745.

Five days later the British launched a sneak attack at midnight on two of the last remaining French ships, the Prudent and Bienfaisant. They slipped aboard, released the English prisoners held on the ships and then set fire to the ship’s magazines. Once the French realized what was happening they immediately fired back at the English ships. Within hours, the Prudent was in flames and the Bienfaisant had been sunk.

To those inside the fortress it must have seemed like the British and Americans were everywhere. Their canons dominated the hills around the city, their ships clogged the bay, British soldiers had taken up key positions in trenches along the perimeter of the city, and a steady barrage of canon fire had wreaked havoc on the city. The British lines had moved up so close that their front lines could pick off the French soldiers one by one on the ramparts above the city. One habitant wrote,

Not a house in the whole place but has felt the force of their cannonade. Between yesterday morning and seven o’clock to-night from a thousand to twelve hundred shells have fallen inside the town, while at least forty cannon have been firing incessantly as well. The surgeons have to run at many a cry of ‘Ware Shell!’ for fear lest they should share the patients’ fate.17

Finally de Drucour agreed to sue for peace. The terms were exceedingly humiliating for the French troops, but without them the safety of the civilians could not be ensured. Drucour had to content himself with the knowledge that he had prevented an attack on Quebec City; it was far too late for the British to continue their attack, at least that year. So the French surrendered and de Drucour was shipped as a prisoner to Britain. Louisbourg was once more in British and American hands. The British continued in their attempts to rid the Atlantic coast of French settlements and in 1759 would use Louisbourg as a launching point for an attack on Quebec. That invasion would be Louisbourg’s last. In the 1760s the fort was razed by British soldiers who did not want to see it returned to the French in any future peace treaty.18