CHAPTER FOUR:

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY

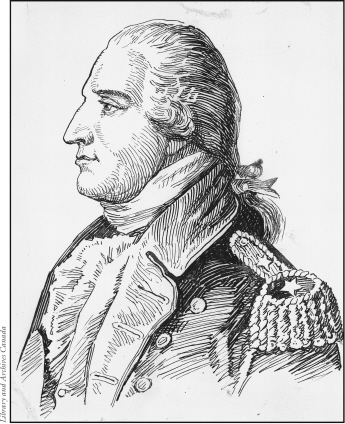

While Wolfe’s career ended on the Plains of Abraham, the career of one of his most trusted lieutenants began there. Guy Carleton had been the officer to whom Wolfe entrusted construction of the British batteries. When war once more brewed on the continent, Carleton would be the man who the British government allowed to control defences for Quebec. Other than two tiny islands at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, the French had abandoned the Canadian colonies. But the British and French were no longer the only ones interested in eastern Canada.

For years the population of the 13 British colonies south of the St. Lawrence had separately brooded over taxation and attempts by the British to limit colonization of the North American west. In the spring of 1775, the brooding exploded into violent confrontation near the towns of Concord and Lexington. Those 13 colonies joined the battle to dislodge their British masters.

They had once hoped to be 14.

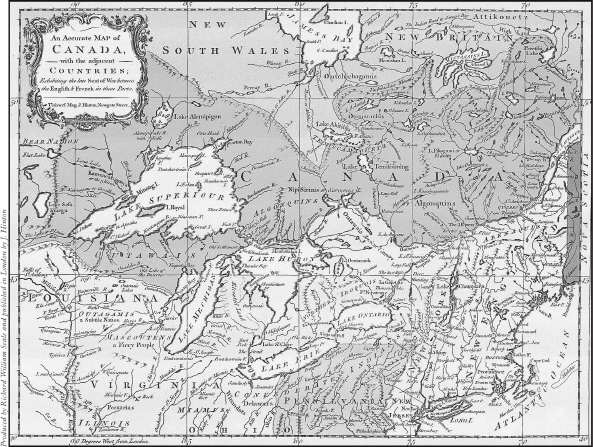

Quebec was just one of several colonies invited to join the Continental Congress in their fight against British tyranny in 1774, but it was considered the ideal prize. The hated Quebec Act had greatly enlarged Quebec’s borders and the colony encased the entire Ohio Valley, among other choice territories. The Americans labelled the act one of the Intolerable Acts and called for its immediate revocation by the British. The territorial slights were bad enough but the Canadians were also denied habeas corpus, trial by jury, and representative government under the act. Surely, the Americans reasoned, despite the grants of land, the French Canadians were as outraged by that as they were. It did not occur to the Americans that the French Canadians would not embrace the idea of ridding themselves of the British yoke. The Quebec Act had also guaranteed the French Canadians lan guage and religious freedoms. That alarmed the American leaders, though it must have reassured the Canadians.

The delegates to the Congress drafted a letter and had it translated into French. Two thousand copies were printed and delivered to Canada. In the open letter to the citizens of Quebec, distributed on October 26, 1774, the Americans urged the Canadians to join their cause and become the 14th colony.

Seize the opportunity presented to you by Providence itself. You have been conquered into liberty, if you act as you ought. This work is not of man. You are a small people, compared to those who with open arms invite you into a fellowship. A moment’s reflection should convince you which will be most for your interest and happiness, to have all the rest of North-America your unalterable friends, or your inveterate enemies. The injuries of Boston have roused and associated every colony, from Nova-Scotia to Georgia. Your province is the only link wanting, to compleat the bright and strong chain of union. Nature has joined your country to theirs. Do you join your political interests. For their own sakes, they never will desert or betray you. Be assured, that the happiness of a people inevitably depends on their liberty, and their spirit to assert it. The value and extent of the advantages tendered to you are immense.

The colonies’ arguments seemed, to them at least, to be perfectly sound and logical. Quebec was joined to the American colonies by geography; it only made sense that the colonies forge political ties as well. To add more punch to their argument they pointed out that Quebec was much smaller and less populous than the rest of the colonies and therefore it would be in Quebeckers best interest to count the Americans as friends rather than enemies. What the Americans did not include in the letter was that they were equally perturbed by the clauses in the Act that ensured the preservation of the French language and gifted numerous rights to French Catholics and perks to the French Catholic clergy. A young Alexander Hamilton, who would later earn fame as one of the founding fathers of the United States, even penned a pamphlet in which he warned that another Inquisition was imminent and American heretics would soon be burning at the stake.

When their first letter was ignored, the Americans sent another on May 29, 1775. That time they entreated the Canadians to join the cause, arguing quite eloquently that they considered the Canadians friends and disliked the idea of being forced to consider them enemies.

In Canada, unsettled by events in the south, the British governor, Sir Guy Carleton, called up the local militia. But having lent two regiments of regulars to the defence of Boston, he had just 800 men at his disposal to protect all of Quebec. He needed the militia but no one wanted to join. The habitants were annoyed that the power to tithe had been restored to the Catholic Church and the Seigneuries, and they were not about to risk their lives to protect them. They were also tired of war and of their farms and fields serving as battlegrounds for foreign troops. Both the British and the Americans had drastically misjudged the Canadians. They were not willing to join the revolution but they were not interested in actively resisting it either. “We have nothing to fear from them while we are in a state of prosperity,” Carleton wrote, “and nothing to hope for when in distress. I speak of the People at large; there are some among them who are guided by sentiments of honour, but the multitude are influenced by fears of gain, or fear of punishment.”1

While Governor Carleton accepted that the French were allies of convenience only and could not be counted on to defend the country, the Americans refused to accept that the French would not eventually embrace their cause. Popular wisdom within Congress suggested that it was only a matter of time before the oppressed French joined with their American liberators. They just needed to be convinced that the Americans were serious. The way to do that, many suggested, was to invade the country. Once the Americans were at their door, the French would embrace them. Canada, George Washington firmly believed, was ripe for the taking. A young colonel by the name of Benedict Arnold was dispatched to open up the lightly defended route to Lake Champlain. He struck first at Ticonderoga (Fort Carillon), where they met a brief challenge from the single sentry and then roused the commander of the fort from his sleep so he could surrender. Less than 50 men defended Ticonderoga.

Crown Point, the next fort in their path, was even more lightly defended: nine British soldiers guarded the fort. They wisely offered the Americans terms. Buoyed by his quick successes, Arnold ventured over the border to attack Fort St.-Jean. Lacking sufficient troops to hold the fort, he satisfied himself by burning a British ship and helping himself to some of the British stores.

The road to Canada was wide open. Congress was finally ready to act and plans were laid for an invasion. It was to be a two-pronged attack. The first 2,000 man force would be lead by General Philip Schuyler and would use a route that would take the army across Lake Champlain and then up the Richelieu River to invade Montreal and then Quebec City. A second force of just over 1,500 men, commanded by Benedict Arnold, would launch from Boston and head directly to Quebec City.

Benedict Arnold, American general, traitor, and would-be conqueror of Canada.

Schuyler arrived at Ticonderoga in the middle of July and immediately began to train the inexperienced, undisciplined troops. By early September he finally felt they were ready and he led them along Lake Champlain to the tiny island of Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River. By the time the troops had arrived on the island, Schuyler was ill. Eventually he grew too ill to lead and ceded command to Brigadier-General Richard Montgomery, who launched a series of quick raids into Canada. The focus of the raids was the British controlled fort of St.-Jean.

Fort St.-Jean had been on the alert since Arnold’s raid in May. Governor Carleton had dispatched 140 regulars, accompanied by 50 members of the Montreal militia. Additional troops of Native warriors were assigned to patrol around the fort. As the sole guard on the road to Montreal, Fort St.-Jean was a critical element in controlling the colony; Carleton was as determined to protect it as Montgomery was to conquer it. The first attempt by Montgomery, on September 7, failed miserably. Quebec newspapers reported that a mere 60 Native warriors had driven off nearly 1,500 American soldiers. Worse news awaited the Americans. An American sympathizer living near Fort St.-Jean, Moses Haven, arrived with the news that while the habitants were sympathetic to their cause, they had no intention of joining the Americans until there was clear evidence they would be victorious.

Not all Canadians remained neutral. Mistreatment by the Americans encouraged some to actively support the British. Others, for various reasons, actively worked for the Americans. When war broke out, James Livingston, a resident of Montreal, recruited an army of men from Chambly, Quebec, to aid the Americans. He was eventually given commanded of that army, known as the First Canadian Regiment of the Continental Army.

Montgomery decided they might have better luck with a night attack. Two days later he led a 1,000 strong force back up the river. While Montgomery and several other officers waited by the boats, his men scattered into the woods that lay between the river and the fort. In the confusion of the dark woods the Americans began to fire on one another, and they made a hasty retreat back to boats. A furious Montgomery sent them back out again, but this time the Americans met a small party of Native warriors and habitants. Once again the troops retreated to the boats. As their commanders met to discuss a new strategy, rumours spread that a British warship was on its way. This sparked a mass panic and the Americans fled back to Île-aux-Noix, almost leaving their commanders behind.

Although their attempts to take the fort were unsuccessful the Americans surrounded it, essentially cutting it off from the rest of Quebec. The same sickness that had felled Schuyler, exacerbated by the damp swampy ground of the island, began infecting many of the American soldiers. To make matters worse, several days of stormy weather delayed the next attempt on Fort St.-Jean. The Americans had more luck on September 17, when they managed to capture a supply wagon headed toward the fort and drive back the Canadian militia that had ventured out to retrieve it.

Despite their efforts, the Americans could not draw out the main force and the Canadians refused to surrender. But with hundreds of women and children inside, and food supplies running low, it was only a matter of time. Fort Chambly, to the east of Fort St.-Jean, had fallen on September 20. Montgomery dispatched Ethan Allen’s forces to guard the road to Montreal. Not content with simply enforcing the siege, Allen took his 250 men to the gates of Montreal. There they engaged with a smaller Canadian and Native force before breaking ranks and retreating back toward Fort St.-Jean. Carleton bolstered the troops and gathered 2,000 Canadian militiamen to defend Montreal. But when the siege dragged on and no orders were given to relieve them, the men drifted back to their homes and farms for the fall harvest. The Americans continued to tighten their hold and finally, on November 3, as an early fall snow storm set in, Fort St.-Jean capitulated

Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen, a businessman, farmer, and experienced guerrilla leader, was best known as the leader of the Green Mountain Boys, a fiercely independent paramilitary militia that had formed in southern Vermont in the decade before the Revolutionary War. By 1775, Allen and his “boys” were lending their substantial military experience to the war effort, and the revolutionary government turned to them to help with the capture of Ticonderoga.

On November 17, Carleton arrived in Quebec City where he learned that a second force was headed toward him from Boston. Montgomery arrived two weeks later and set up camp outside the city. Once again the two generals had a common objective. Both felt that the city of Quebec was the key to controlling Canada. Despite the fact that his troops controlled every other major fort within Quebec and had overrun most of the colony, Montgomery refused to claim victory. “I need not tell you,” he wrote, “till Quebeck is taken, Canada is unconquered.”2 While Carleton believed that Quebec would be his last stand against the American invasion and that holding the city was crucial, he was less convinced that he would be successful. He mistrusted the citizenry. “Could the people in the town be depended upon,” Carleton wrote to Lord Dartmouth. “I should flatter myself, we might hold out…. But, we have as many enemies within, and a foolish people, dupes to those traitors, with the natural fears of men unused to war, I think our fate extremely doubtful, to say nothing worse.”3

His distrust of the populace led Carleton to issue a proclamation shortly after his arrival in Quebec City, “In order to rid the town of all useless, disloyal and treacherous persons … I do hereby strictly order all persons who have refused to enrol their names in the militia lists and to take up arms to quit the town in four days together with their wives and children under pain of being treated as rebels or spies.”4

But the people of Quebec were not as sympathetic toward the American cause as Carleton feared. They might be opportunistic — many had sold the American Army beef and other goods during their occupation of Canada — but as soon as the American’s cash ran out, the habitants refused them credit. And when the army retaliated by raiding farms and capturing supply wagons to take what they needed, they lost any Canadian sympathy they might have gained.

When Montgomery arrived outside Quebec on November 17, 1775, he was met by a second American force. Benedict Arnold had finally arrived in Canada, but his force of 1,500 had been halved by disease and desertion. A dearth of supplies and the arduous journey they had undertaken to get to Quebec had destroyed the spirits of the remainder. This was not the quick thrust into Canada that George Washington had envisioned when he pitched his plan to congress,

I am now to inform the Honourable Congress that, encouraged by the repeated declarations of the Canadians and Natives, and urged by their requests, I have detached Col. Arnold, with one thousand men, to penetrate into Canada by way of Kennebeck River, and, if possible, to make himself master of Quebeck … I made all possible inquiry as to the distance, the safety of the route, and the danger of the season being too far advanced, but found nothing in either to deter me from proceeding, more especially as it met with very general approbation from all whom I consulted upon it … For the satisfaction of the Congress, I here enclose a copy of the proposed route.5

The “straight line of two hundred and ten miles” was actually more than twice that length and passed through a rough tangle of woods and swamps that forced the troops to travel a winding route. The falls and carrying places they encountered were neither small nor short. Worse than the hardships offered by nature was the fact that the area was still a virtual no man’s land, unsettled and unmapped. There would be no villages or settlements where the soldiers could regroup and replenish their supplies. Arnold and his 1,500 men had no idea what they would face when they set out from Boston with their heavy canoes laden with supplies. The plan had called for Arnold’s force to move through the Kennebec Valley to the Chaudière River and then on to the St. Lawrence. But the Kennebec River was a virtually unnavigable morass of rocks and rapids, and the tributary they were to follow, known as the Dead River, was even worse. The aptly named Chaudière (boiler) was equally unfit for navigation. The soldiers were frequently forced to carry their canoes overland and on many days they could only cover a mere five kilometres.6 “Our march has been attended with an amazing deal of fatigue … I have been deceived in every account of our route, which is longer and has been attended with a thousand difficulties I never apprehended,”7 Arnold wrote.

Arnold and his men struggled to control their canoes in the churning water. At one point a flash flood destroyed many of their supplies and canoes. By the time they reached the Chaudière a full third of their number had turned back and many of their canoes had been lost or abandoned in the thick swamp and bush of their latest portage. An attempt to float their supplies down the Chaudière on rafts had resulted in the loss of both provisions and ammunition, and the soldiers were forced to eat their shoe leather and the few dogs that had accompanied them, in order to survive.

“We had all along aided our weaker brethren,” Private George Morison recorded in his journal, “but the dreadful moment had now arrived when these friendly offices could no longer be performed. Many of the men began to fall behind, and those in any condition to march were scarcely able to support themselves, so that it was impossible to bring them along; if we tarried with them we must all have perished.”8

By the time Arnold and his men appeared on the Plains of Abraham on November 14, their numbers had dwindled to a little over 700. The remaining men were starved and sickened by the arduous journey. The fact that they had persisted in the face of such adversity and such horrific conditions hardened their resolve. Arnold himself was still determined to take Quebec, and with typical bravado sent a white flag of truce into the city to demand its immediate surrender.

With Carleton still not yet arrived from Montreal, command of the Quebec garrison was in the hands of Lieutenant-Colonel Allan MacLean, who had arrived a mere two days ahead of Arnold and was greeted by a city full of fear and pessimism. The lieutenant-governor, Hector Cramahé, was terrified by the sight of Arnold’s force. There was talk of immediately lowering the flag even before Arnold sent his demand for the city’s surrender. MacLean, a gruff Scotsman, angrily took control and refused to open the gates to admit the flag of truce. There would be no more talk of defeat.

With no cannon or heavy guns, Arnold was in no position to force the issue and MacLean kept his men well within the protections of the city walls. After waiting for a few days, Arnold withdrew his men to Pointe-aux-Trembles to wait for reinforcements from Montgomery. Montgomery finally arrived on December 2, with 500 troops and supplies. Three days later the combined forces once more stood on the Plains of Abraham. As Wolfe’s right-hand man, Carleton knew first-hand the dangers in leaving the safety of the walls of the city to engage the enemy; he had no intention of repeating Montcalm’s mistake. For almost 30 days the Americans laid siege to the city. When it finally became clear that the Canadians would not venture from the city to lift the siege, Montgomery and Arnold decided to lift it themselves.

As had happened to Wolfe during his siege, winter was approaching and the Americans were ill-prepared to survive a lengthy wait in the midst of a cruel Canadian winter. They had another incentive though: over half of Montgomery and Arnold’s men were due to be released from their service on January 1. It was unlikely they would agree to stay. Morale was low, conditions were horrible, and it was believed that few would voluntarily stay to fight a war on foreign soil. An American deserter came to Quebec and told James Bain, captain of the British militia, about the dispirited state of the attacking army. The man claimed that all the people from the old country wished to be at home and that they had no wish to attack the town. Their leaders were eager to act before more men deserted.

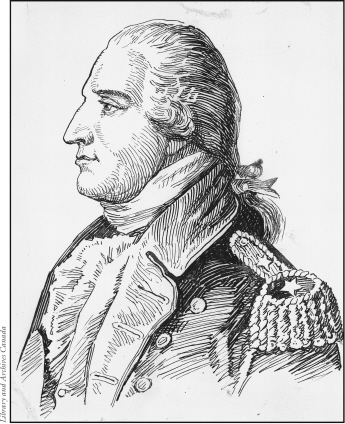

On December 31, in the midst of one of the raging snowstorms that Quebec City is famous for, the Americans launched their attack. Two regiments launched feint attacks on the Plains of Abraham with the goal of distracting Carleton’s men from the real invasions being lead separately by Montgomery and Arnold. Arnold’s role was to advance along between St. Charles and the Plains in order to storm the Lower Town. From there he and his men would make their way through the mazes of houses, wharves, and storehouses toward the gate that lead into the more heavily fortified Upper Town. They believed that if they could reach the gate they could easily breach its defences. Montgomery’s role was to take the higher route into Lower Town, which would take his troops between the cliffs of Cape Diamond and the St. Lawrence.

Attack on Quebec by General Montgomery, Morning of 31st December, 1775.

Observing the assault from behind the walls of Upper Town, Carleton dispatched a troop of 400 men, under MacLean, to attack the rear of Arnold’s troops. Arnold’s men waded through knee-deep snow, many of them wearing tiny slips of paper pinned to their hats that read “Liberty or Death.” They took the first battery they encountered but Arnold was wounded in the effort and carried out of the battle. His men were quickly stalled at the second battery where they also faced a deep trench dug to prevent their forces from entering Upper Town. Then the boom of cannon and musket fire sounded behind them. MacLean had arrived.

The Death of Montgomery at Quebec, December 31, 1775.

The Americans began to fall like toy soldiers as their enemies fired at them from ahead and behind. There was nowhere for them to go. By the time the barrage lessened enough for them to surrender, nearly 100 Americans had been killed or wounded by enemy fire and dozens of others had drowned while trying to flee across the lightly frozen river. Another 400 American troops were taken prisoner, nearly every remaining member of Arnold’s regiment.

Montgomery had his own problems. Several entrenchments had been layered between the cliffs and the St. Lawrence River. In the midst of the fog of musket and cannon fire, Montgomery and his men were unable to see that the enemy entrenchments were only lightly defended by the handful of troops that Carleton thought he could spare. Like Arnold, Montgomery breached the first with relative ease. But in leading the charge to the second, Montgomery and many of his senior officers were killed. The remainder of the soldiers panicked and fled. Carleton, who reported a mere six of him men killed and barely a score wounded, wisely refused to pursue the retreating Americans, choosing instead to stay behind his walls and wait for the anticipated reinforcements he expected to arrive in the spring.

Despite these humiliating defeats, Arnold steadfastly refused to lift the siege and began to prepare to spend the winter outside the walls of Quebec. Plagued by near continual desertions, he sent to Congress for reinforcements hoping they would arrive before expected reinforcements arrived from Britain. In the interim, both sides made occasional forays against each other as pockets of militia stationed outside the fort from both sides engaged. But these skirmishes had little effect on the siege.

Congress did not want to give up their pursuit of the 14th colony any more than Arnold did. In a third open letter to the inhabitants of Quebec, published on January 25, 1776, they assured the Canadians that, “We will never abandon you to the unrelenting fury of your and our enemies; two Battalions have already received orders to march to Canada.”9 Reinforcements did arrive, although among the Americans they were greatly reduced by a smallpox epidemic that was rapidly sweeping through the ranks. Arnold, still wounded, was sent to Montreal where he found growing resentment toward the American presence.

Montgomery had left Montreal in the command of Brigadier-General David Wooster. At first, the general had established good relations with the population, but the relationship slowly eroded as Wooster arrested Loyalists and threatened the arrest of those with Loyalist leanings. He imprisoned a number of local militia who had refused to give up their commissions, and completely disarmed several communities who he suspected of being potentially disloyal. Faced with this growing resentment and the very real possibility of an insurrection, the Americans sent Wooster to Quebec City and replaced him with Arnold. They also sent a delegation to Quebec City, consisting of a Catholic priest and a French printer from Philadelphia, who would be transported to Canada and given monies to re-establish himself, his family, and business there. In exchange, the printer would use his print shop to help promote American interests in Canada. Three members of congress, including Benjamin Franklin, rounded out the delegation. Their mission was primarily one of public relations, to extend the message of common ground to the French Canadians and to assure them that their rights would be protected.

The delegation was also granted the funds to raise several regiments from among the French Canadians, who they expected would embrace their cause. Unfortunately, most of their money was paper — Continental Money — which the French Canadians were rejecting from the American Army; the French preferred gold.

What Franklin and his fellow commissioners discovered in Quebec dismayed them. He informed Congress that it was

impossible to give you a just idea of the lowness of the Continental credit here from the want of hard money and the prejudice it is to our affairs … The Tories will not trust us a farthing … Our enemies take advantage of this distress to make us look contemptible in the eyes of Canadians who have been provoked by the violence of our military in exacting provisions and services from them without pay and conduct towards a people who suffered us to enter their country as friends that the most urgent necessity can scarce excuse since it contributed much to the change of their good dispositions towards us into enmity and makes them wish our departure.10

Franklin and his fellow commissioners were pestered with demands for reimbursement so that it was impossible for them to deliver their intended message. In a final and ominous report to Congress they were blunt in their assessment of the situation in Quebec. If Congress could not find the cash to support the army in Quebec, they had better withdraw it before the “inhabitants are become our enemies.” 11 Franklin’s was not the only voice pleading for help. Schuyler entreated congress to send his suffering armies in Quebec “powder and pork”12 and both he and Franklin warned Congress that necessity was forcing the armies to go into debt, a debt that had climbed to well over $10,000.

Reproduction of a 1761 map: “An Accurate Map of Canada with the Adjacent Countries.”

There was worse news for the American delegation. Despite the support of the priest who accompanied them, the influential Catholic clergy refused to support their cause, pointing out that the Quebec Act had already given them what they wanted. The French printer had not yet been able to print anything that could be used to sway the populace. Then came the devastating news that the American Army at Quebec City was in a panicked retreat. British ships had been sighted coming up the St. Lawrence, bringing thousands of reinforceReproduction ments. After 11 days in Montreal, the venerable Ben Franklin, who had never before shied from controversy or hardship, decided that the problems in Quebec were too many and too complicated for his mission to fix and returned to New York.

In the meantime, Carleton hastily gathered his reinforcements to chase down the retreating Americans. There were several pitched battles at Les Cèdres, Quinze-Chênes, and Trois-Rivières, which all ended with American losses.

On May 6, 1776, a large contingent of British reinforcements arrived at Trois-Rivières, undetected by the Americans who occupied Sorel, a few kilometres upriver. The Americans, believing that Trois-Rivières was being held by only a small contingent of British soldiers, raided the settlement. Not only were they unaware of the strength of the British garrison there, they were also wholly ignorant of the terrain. After slogging through a thick swamp, the American troops emerged to face a huge force of British regulars. The Americans scattered back into the swamp. Two hundred American soldiers, including most of the senior officers, were captured. Carleton refused to press his advantage and did not take his troops up the St. Lawrence to make a play for Quebec until the middle of June. He found Sorel abandoned.

Even Arnold was ready to give up. “Let us quit and secure our own country before it is too late,”13 he wrote. On May 15, he and the American Army, which numbered more than 5,000 in and around Montreal, first attempted to burn down the city then abandoned it and began their retreat back through the Richelieu River to Lake Champlain. They took refuge at Île-aux-Noix but were promptly ousted by the British. At Fort St.-Jean they managed to get away only moments before the British forces arrived. Throughout the summer and into the fall of 1776, Arnold managed to hold the British at bay with a fleet he had built up after his initial taking of Crown Point in 1775, but was finally defeated on October 11, and forced to withdraw from that fort to Ticonderoga. Carleton decided that the Americans were too strong to oust and he contented himself to wait at Crown Point. Finally, on November 2, he pulled his troops from Crown Point and withdrew to spend the winter in Quebec.

The campaign to capture Quebec was an unmitigated disaster for the Americans. Not only had they failed in their attempt to take Canada by force, but they had also failed to convince the Canadians that their future could be secured by uniting with their rebellious neighbours to the south. It would be many years before relationships along the border were sufficiently repaired. The only saving grace for the Americans was that Arnold’s tiny naval fleet had held off the British long enough that it had discouraged a full-scale British invasion along Chesapeake Bay, which might have ended the entire revolution. The Americans made one last attempt to secure Quebec at the Paris Peace Conference, which created the United States of America. American negotiator Ben Franklin suggested that all of Quebec be ceded to the Americans, but in the end they received only the Ohio territory.