Doctoral ceremony in large hall. Serious, but not wholly accurate speech in Latin. Then my last lecture at Rhodes House on the mathematical methods of field theory. The dean slept wonderfully in the first row. Frightfully well-behaved and friendly audience. Afternoon nap at Lindemann’s. Meal in college and finally pacifist students in cute old private house. Great political maturity among the Englishmen. How pitiful are our students by comparison!

Comment by Einstein about a day in Oxford in his travel diary, May 1931

In the 1920s, England had taken Einstein to its heart, following his initial burst of scientific fame in 1919 and his first personal visit to Manchester and London in 1921. In 1924, George Bernard Shaw – who had met Einstein (a decided fan of Shaw’s work) at the house of Lord Haldane – privately informed him that ‘You are the only sort of man in whose existence I see much hope for this deplorable world’, while frankly admitting his own inability to understand Einstein’s theory. In 1925, Bertrand Russell (for whose book Political Ideals Einstein had written an enthusiastic introduction to its German edition in 1922) published an introductory book, The ABC of Relativity. Russell kicked off with this come-on: ‘Everybody knows that Einstein did something astonishing, but very few people know exactly what it was that he did.’ At the same time the poet Sir John Squire remarked epigrammatically, in extending two classic lines about Newton written by Alexander Pope in 1730:

Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night.

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

It did not last: the Devil howling ‘Ho!

Let Einstein be!’ restored the status quo.

In 1925, the Royal Society awarded Einstein its highest honour, the Copley Medal, which had been given to Faraday in 1838. The Society’s secretary, Sir James Jeans, while officially informing Einstein, added a personal touch: ‘I think you are the youngest recipient in the two hundred years or so since it has been awarded; in any case if you are not, I think you ought to be.’

By 1930, according to Shaw, Einstein belonged to the pantheon of the immortals. Speaking at a public dinner in London for a Jewish cause where Einstein was the guest of honour, Shaw counted him among the ‘makers of universes’, in the company of Pythagoras, Ptolemy, Aristotle, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton – ‘not makers of empires’. He added: ‘and when they have made those universes their hands are unstained by the blood of any human being on earth’. (A humble Einstein responded: ‘I, personally, thank you for the unforgettable words which you have addressed to my mythical namesake, who has made my life so burdensome, who, in spite of his awkwardness and respectable dimension, is, after all, a very harmless fellow.’)

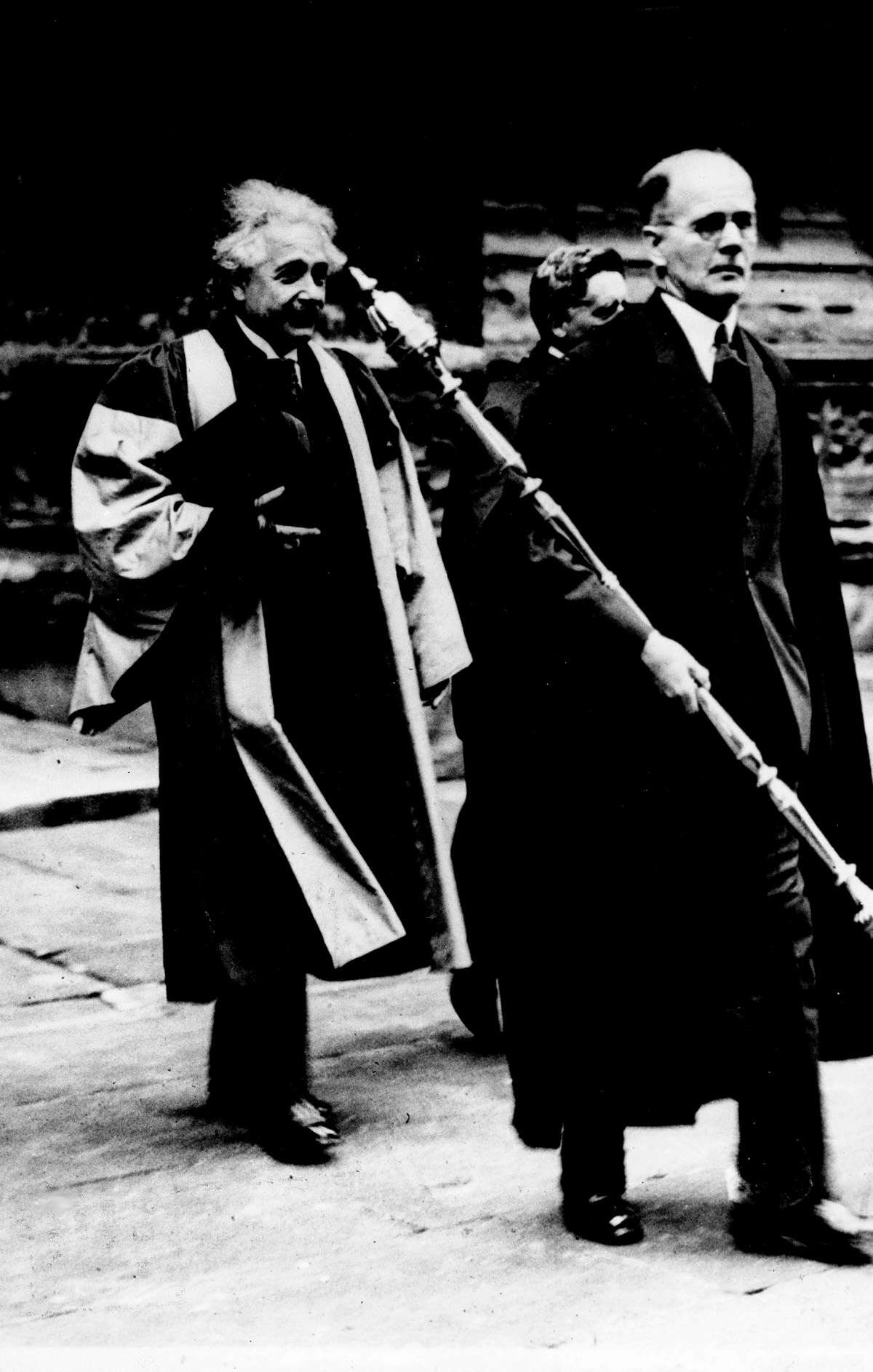

Einstein near the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, during his doctoral ceremony, May 1931. The public oration about Einstein, given in Latin, failed to translate ‘relativity’ or to mention Isaac Newton.

INTRODUCING FREDERICK LINDEMANN

On 1 May 1931, Lindemann’s chauffeured Rolls Royce collected Einstein from the docks at Southampton when his passenger liner arrived from Hamburg. But instead of heading straight for Oxford in the car, Lindemann broke the journey at Winchester so that Einstein could see the town’s wonderful Gothic cathedral and also pay a surprise visit to the cloistered seclusion of its notably intellectual boys’ public school, Winchester College, founded in 1382, which has the longest unbroken history of any school in England.

Here, however, Professor Lindemann encountered a problem: the school porter refused to admit him and his guest on the grounds that the school was closed because the boys were at work. Attempts to persuade the porter to make an exception for Albert Einstein failed – no matter how many names of Lindemann’s eminent friends, including the prime minister’s, he dropped. Finally, Lindemann said he had a message to give to a boy, John Griffiths, from his mathematician–physicist father in Oxford, who worked with Lindemann at the Clarendon Laboratory. This recommendation worked the necessary magic, and a passing junior boy was sent to find Griffiths, who now takes up the story (as he recalled in the school’s magazine, The Trusty Servant, half a century later).

‘I looked out from the window of Second Chamber, and saw the immaculately attired Lindemann standing about half-way along Middle Sands, attended by a short figure, dressed in a Middle-European style cape with frizzy hair escaping from a kind of skull cap.’ But when young Griffiths, who was shortly due in class, hurried out to be introduced to Professor Einstein, he knew that his school German was utterly inadequate for communication. Fortunately, Lindemann – a fluent speaker of German – proved to be a ‘masterly’ interpreter. The three of them went on a quick tour of some of the school buildings. Since Einstein wanted to see where the boys worked, they visited one of the classrooms. Here, on the ancient walls, marble plaques commemorating past members of the school ‘intrigued Einstein beyond measure’. A little later, on the way out, they saw another room, used as a changing-room for football, cricket and other sports. It too contained marble plaques on its walls and beneath them were pegs with sweaty games-clothes hanging from the hooks. Einstein, despite a total lack of interest in team sports, stopped to ponder. ‘But the Great Mind remained perplexed: the seconds ticked by as its owner stood plunged in thought.’ Then at last the connection dawned: ‘Ach! Ich verstehe: der Geist der Gestorbenen geht in die Beinkleider der Lebenden hinüber,’ Einstein remarked. ‘The sense eluded me then,’ remembered Griffiths, but ‘well do I remember Lindemann’s smile as he translated for my benefit: “The spirit of the departed passes into the trousers of the living.”’

And indeed the unique encounter with Einstein and Lindemann had an inspiring coda. For after Einstein reached Oxford, he heard through Griffiths’ father of a successful textbook, Readable Relativity, by a Winchester schoolmaster, C. V. Durrell, which Griffiths junior had been studying in class. Einstein naturally wanted to see a copy. So the schoolboy copy was sent to Oxford, including its doodles, marginalia and all. Not long afterwards, ‘my Dad wrote to say that Einstein had hugely enjoyed it’ and commented that: ‘No German schoolmaster would ever have thought of doing it like that, or if he had, have done it so well.’ Soon after, Griffiths senior sent the book back, now with Einstein’s signature on its inside cover. Later, the heirloom passed into the hands of John Griffiths’ younger son, Robin, who became a mathematician.

Apart from its charm, the story of this flying visit to Winchester captures some of the key elements in Einstein’s Anglophilia: not least his admiration for the English belief in tradition. ‘More than any other people, you Englishmen have carefully cultivated the bond of tradition and preserved the living and conscious continuity of successive generations. You have in this way endowed with vitality and reality the distinctive soul of your people and the soaring soul of humanity,’ Einstein told the Royal Society in a message celebrating the bicentenary of Newton’s death in 1927.

It also reveals something of Einstein’s talented and worldly English host, Lindemann. On closer acquaintance he turns out to be an intriguing character, if diametrically opposite to Einstein in intellect, interests, politics and personality, not to mention dress sense. Even so, their relationship was one of both mutual respect and considerable warmth, which undoubtedly enhanced Einstein’s already favourable opinion of England.

Though born in Germany (in 1886, seven years after Einstein), the son of a decidedly wealthy German father and an American mother, Lindemann had been brought up and educated as a British citizen. Indeed, all his life he resented the accident of his birthplace and came to regard himself as more English than the English, with an accompanying distrust for certain aspects of Germany. In his mid-teens, however, he returned to Germany for further schooling and then attended the University of Berlin. After graduating, he earned a doctorate in physics working under Walther Nernst who, as we know, sent him to the Solvay Congress in 1911, where he first encountered and befriended Einstein. Just before the outbreak of war in August 1914, however, Lindemann left Germany, to avoid being interned, and settled for good in England. In 1915, after failing to obtain a military commission because of his German background (a rejection which rattled him), he joined the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough, learned to fly the following year and soon became semi-legendary for having extricated himself from a potentially lethal aircraft spin through rapid mental calculation, navigational skill and sheer courage, while empirically testing his own theory to explain the nature of the spin. A few months after the end of the war in 1918, he was appointed to the professorship in physics at Oxford’s Clarendon Laboratory which he would hold for the rest of his scientific career. He was also a fellow of Wadham College – at the time of Einstein’s first visit to Oxford in 1921 – and in 1922 he joined Christ Church. There he would reside in a suite of fine rooms until his death in 1957, and be known as ‘The Prof’, and, after 1941, as Lord Cherwell, the scientific adviser and confidant of Sir Winston Churchill.

As a physicist, Lindemann was highly rated, but never placed in the top rank. ‘If your father were not such a rich man, you would become a great physicist,’ Nernst once told him. Lindemann ‘was a man of intuition and flair in widely diverse fields, but he never pursued any one subject long enough to become its complete master. Much of his brilliance was shown in discussion at scientific conferences, and has not survived in published form,’ commented historian Lord Robert Blake, a Christ Church colleague, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. ‘For this reason later generations have not found it easy to understand the high esteem in which he was held by such persons as Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Max Born, Ernest Rutherford, and Henri Poincaré.’ This assessment is confirmed by Einstein’s own private summary of Lindemann, as reported by Harrod: ‘The Prof., so it went, was essentially an amateur; he had ideas, which he never worked out properly; but he had a thorough comprehension of physics. If something new came up, he could rapidly assess its significance for physics as a whole, and there were very few people in the world who could do that.’

Lindemann’s political views explain his appeal to Churchill. They were well to the right (though never sympathetic to Nazism). ‘He was an out-and-out inequalitarian who believed in hierarchy, order, a ruling class, inherited wealth, hereditary titles, and white supremacy (the passing of which he regarded as the most significant change in the twentieth century),’ wrote Blake. When a guest in Christ Church’s Senior Common Room happened to remark ‘One shouldn’t kick a man when he’s down,’ a cynical Lindemann replied, ‘Why not? It’s the best time to do it because then he can’t kick you back.’ He himself became the butt of spiteful jokes because he spent so much time in the 1920s and 1930s moving in British aristocratic circles. Why is Lindemann like a Channel steamer? Answer: Because he runs from pier/peer to pier/peer. Yet in private he was kind-hearted and most generous to those in need, drawing on his wide contacts and personal wealth. Such attitudes – both public and private – underscored his obituary of Einstein for the Daily Telegraph in 1955. Overflowing with respect for Einstein’s science, it was not surprisingly somewhat critical of his liberal and pacifist politics: ‘Like many scientists Einstein was politically rather naïve. He hated violence and war and could not understand why his own natural sweet reasonableness was not universal. Absolutely truthful himself, he tended to be credulous in political questions and was easily and often imposed on by unscrupulous individuals and groups.’ Yet, Lindemann concluded: ‘As a man his simplicity and kindliness, his unpretentious interest in others and his sense of humour charmed all who knew him.’

Undoubtedly, Lindemann’s difficult personality polarised his contemporaries (as it does even today). ‘It has often been asked how a prickly, eccentric, arrogant, sarcastic and uncooperative man – to use some of the adjectives from time to time levelled against Lindemann – could have developed and sustained such a warm friendship with Churchill,’ according to Adrian Fort, Lindemann’s most recent biographer. ‘The answer is of course that he did not display those characteristics to Churchill.’ Presumably the same was true in Lindemann’s somewhat less warm, and certainly less intense, friendship with Einstein.

OXFORD AND THE RHODES MEMORIAL LECTURES

It was in 1927 that Lindemann began to court Einstein for a second visit to Oxford. He had the support of the Rhodes Trust, which wished to launch the Rhodes Memorial Lectures in Oxford in memory of Cecil Rhodes, the British-born Victorian businessman, mining magnate and politician in southern Africa, whose strong support for imperialism would presumably have appealed to Lindemann – if rather less to Einstein (and not at all to most Oxford dons today). The trustees’ aim was to attract to Oxford leading figures in public life, the arts, letters, business or science from around the world, whose presence would counteract the prevailing insularity of the university (such as had been exposed in the inadequate 1919 Oxford debate on relativity between Lindemann and the philosophers Smith and Joseph). To cite the devastating words of a British government commission of inquiry into the universities at Oxford and Cambridge, reporting in 1922: ‘It is a disaster that, at a moment when we have become far more deeply involved than ever before in the affairs of countries overseas, our highest academical class is condemned through poverty to knowing little or nothing of life or learning outside this island.’

Although the Rhodes trustees were conscious of the recondite nature of relativity, and wary of the fact that Einstein would need to speak in German, they pressed ahead with an invitation to him, given his worldwide renown. One of them, the Oxford historian and Liberal politician H. A. L. Fisher, recruited Einstein’s 1921 English host, Lord Haldane, to make the introductory approach. Haldane wrote to Einstein in Berlin in June 1927 introducing the unfamiliar Rhodes lectures: ‘The university and the trustees desire that the lectures should next year be delivered by the foremost man of science in the world, and they are unanimous in their choice of your name.’ Haldane hoped Einstein would accept, not least because this would be ‘very good for Anglo-German relations that the choice should be proclaimed to the world’. As for the subject, it should be ‘just what you select. Not too technical in detail, but extending to anything you please, mathematico-physical or otherwise.’ As for the Oxford audience, it would include ‘learned men as well as the public’. At the end of his letter Haldane mentioned that Lindemann would soon get in touch with the details of the invitation.

Einstein was interested, but he refused, for a mixture of reasons. He frankly explained to Lindemann in July: ‘How gladly would I accept, particularly as I value highly the milieu of English intellectuals, as being the finest circle of men which I have ever come to know.’ Unfortunately, however, scientific commitments to people in Germany would prevent him from being away for such a long time. Secondly, his poor health would make ‘a long stay in foreign and unfamiliar surroundings . . . too great a burden for me, particularly bearing in mind the language difficulty’. Lastly, he modestly confessed that his current work was not at the forefront of physics, as compared with that of some other physicists who would appeal more to an Oxford audience.

But in August he changed his mind, and gave Lindemann encouragement: ‘During the holidays I have often reproached myself because I haven’t accepted your kind invitation to Oxford.’ Perhaps he could come to the university for just four weeks during the next summer term? ‘It is very important to me that in England, where my work has received greater recognition than anywhere else in the world, I should not give the impression of ingratitude.’ However, he realised that following his earlier refusal someone else had probably been invited in his place. In which case, he trusted that Lindemann would make clear to the Rhodes trustees the warmth and gratitude he felt for their proposal.

By now, the American educationist Abraham Flexner had been approached to give the 1928 Rhodes lectures, which he duly delivered at Rhodes House on ‘The idea of a modern university’. (In 1932–33, Flexner would persuade Einstein to join his newly founded Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton.) Einstein was therefore invited to speak in the following year, 1929, and apparently accepted; but again negotiations broke down for reasons of health. In the meantime, the Rhodes lectures began to establish themselves after a well-attended series on world politics given in 1929, not at Rhodes House but at the nearby larger Sheldonian Theatre, by Jan Christiaan Smuts, the South African soldier and statesman. This success renewed the determination of both the trustees and Lindemann to secure agreement from Einstein. At last, following a personal visit to Einstein in Berlin by Lindemann in October 1930, arrangements were finalised. Einstein agreed to visit Oxford for some weeks in May 1931, give the Rhodes lectures, and live in Lindemann’s college, Christ Church.

After his acceptance was publicly announced, there was an ominous comment from the Jewish Telegraph Agency in December 1930: ‘The movement to induce Prof. Einstein to settle permanently in England after his summer stay in England has gained momentum here as a result of a recent report from Berlin to the effect that Einstein may not return to Germany in case the Hitlerites obtain control of that country.’ It was perhaps the first clear portent of political events that would overshadow Einstein’s relationship with England during 1933.

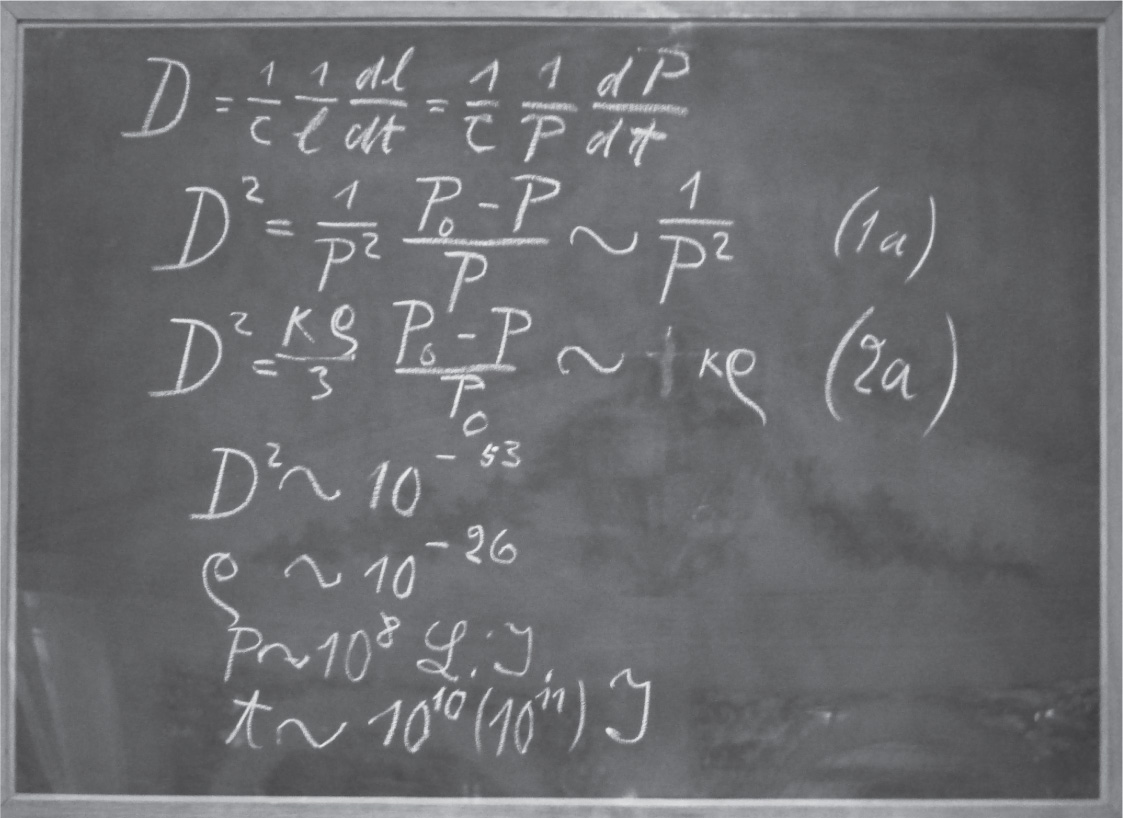

The opening lecture by Einstein took place in the Milner Hall at Rhodes House on 9 May 1931. Given in German (like his other two lectures) without notes but with a blackboard, its English title was simply ‘The theory of relativity’. The second lecture, in the same place on 16 May, dealt with relativity and the expanding universe: a subject then of course in a state of great flux (following Einstein’s abandonment of the cosmological constant a few months before). It required ‘two blackboards, plentifully sprinkled beforehand in the international language of mathematical symbol’ (as The Times reported). The last lecture, also in Rhodes House, on 23 May, immediately after the university had awarded Einstein an honorary doctorate in the Sheldonian Theatre, tackled Einstein’s constantly evolving unified field theory: ‘an account of his attempt to derive both the gravitational and electromagnetic fields by the introduction of a directional spatial structure’, as Nature chose to announce it.

The scientific content of the lectures was of no lasting significance, since it either repeated Einstein’s existing published work on relativity or would quickly be rendered redundant by his (and others’) subsequent ideas. More interesting is the reaction of the very mixed Oxford audience, which included some 500 selected students, to such an unparalleled educational-cum-social occasion.

The Oxford Times captured the atmosphere in two reports on the opening and final Einstein lectures. The first of these, headlined ‘Women and relativity’, remarked on 15 May:

Women in large numbers flocked to hear Prof. Einstein speak on relativity at Rhodes House on Saturday morning. The front of the hall was filled with heads of houses and the back of the hall and the gallery with younger members of the university. It was unfortunate that no interpreter was provided, but Oxford seems to fight shy of interpreters. One wonders how many of those who were present thoroughly understood German, or if they could understand the language in which Prof. Einstein spoke, how many of them could follow the complexities of relativity. Prof. Einstein is a man of medium height with a wealth of black curly hair, already greying. Entirely unaffected, he had charm as well as simplicity of manner, which appealed to his audience.

The second report on 29 May began with a reference to the just-completed doctoral ceremony at the Sheldonian:

Prof. Einstein, wearing his new doctor’s robes, acknowledged the applause which greeted his appearance by smiling and bowing. His manner in beginning his lecture suggested that he was dealing with a difficult part of the subject, and at first he spoke earnestly from the desk, with his hands clasped in front of him, only leaving it occasionally for the blackboard. As the lecture proceeded, not only equations but a singular diagram appeared on the blackboard, and Prof. Einstein gesticulated helpfully in curves with the chalk to explain it. At this point he turned repeatedly from his audience to the board and back. Later, the diagrams were rubbed off in favour of more formulae, and the better informed members of the audience were kept busy taking them down.

By now, at least one less-informed member had fallen asleep, however. The dean of Christ Church, Henry Julian White, a biblical scholar in his seventies, slept soundly during the lecture in the front row, opposite the speaker. Einstein was amused to see this, and perhaps also learned a lesson. For after one of the lectures, he apparently remarked in his curious English that the next time he had to lecture in Oxford, ‘the discourse should be in English delivered’. Hearing this, one of his Oxford don companions, the physiologist John Scott Haldane (brother of Lord Haldane) was heard to murmur in German ‘Bewahre!’ However, Einstein did follow his advice to himself: when he gave his most important lecture in Oxford, the Herbert Spencer lecture in 1933, he had it translated into fluent English and then read it aloud.

Not too surprisingly, given the fluid state of cosmology and of his unified field theory in 1931, Einstein showed almost no interest in preparing his Rhodes lectures for publication – unlike Smuts in 1929, whose lectures were published by the Oxford University Press in 1930. The secretary of the delegates of the press, R. W. Chapman, regarded Einstein’s lectures – however demanding their subject matter might be – as a potential ornament to the publisher’s list, and strongly pursued the possibility of their publication. But Chapman received no reply from Einstein to his follow-up letters and cables. After a final proposal (apparently suggested by Lindemann) – that Einstein might produce a reduced text of about fifty pages – went nowhere, an exasperated Chapman gave up on what he now called ‘l’affaire Einstein’.

Two years later, at a social gathering in Oxford in 1933, Einstein intimated to the warden of Rhodes House, Sir Carleton Allen, that publication was impossible because ‘he had since discovered that everything he had put forward in the lectures was untrue’. He explained, with ‘rather comic contrition’, that ‘in my subject ideas change very rapidly’. ‘I had not the hardihood to say that that was true of most subjects,’ commented Allen, when reporting his conversation with Einstein in a letter to the secretary of the trustees, Lord Lothian. Instead, ‘I suggested that he might publish the lecture with a short note at the end – “I do not believe any of the above”, or words to the effect. He felt, however, that others might take up his ideas and convince him that what he knew to be untrue was true.’ As for Einstein’s vague suggestion that he might write an alternative book, Allen told Lothian ironically that perhaps an Einstein book on ‘My view of Hitler’ or ‘Hitler in time and space’ might help to recoup the large amount that the Rhodes Trust had spent on Einstein. In the end, his Rhodes lectures went entirely unrecorded, apart from an eight-page pamphlet printed in early May 1931, compiled probably with Lindemann’s help, and three non-technical summary reports published in The Times, apparently based on this pamphlet. But the Oxford University Press did at least get to publish Einstein’s 1933 Herbert Spencer lecture.

BLACKBOARD MATTERS

A more immediate source of friction between Einstein and the university was his blackboards. On 16 May, after the second lecture, Einstein told his diary with singular annoyance: ‘The lecture was indeed well-attended and nice. [But] the blackboards were picked up. (Personality cult, with adverse effect on others. One could easily see the jealousy of distinguished English scholars. So I protested; but this was perceived as false modesty.) On arrival [at Christ Church] I felt shattered. Not even a carthorse could endure so much!’

The idea of rescuing and preserving Einstein’s blackboards seems to have come from some Oxford dons who attended his first lecture on 9 May. A memo from the then warden of Rhodes House, Sir Francis Wylie, to one of the trustees, Fisher, dated 13 May, states plainly that ‘Some of the scientists seem to be anxious to secure for preservation in the Museum the blackboard upon which Einstein draws. I was first approached about it by de Beer, who is a fellow of Merton, and now Gunther has written to me, asking whether, if it is desired, the blackboard with Einstein’s figures on it may be given to the university.’

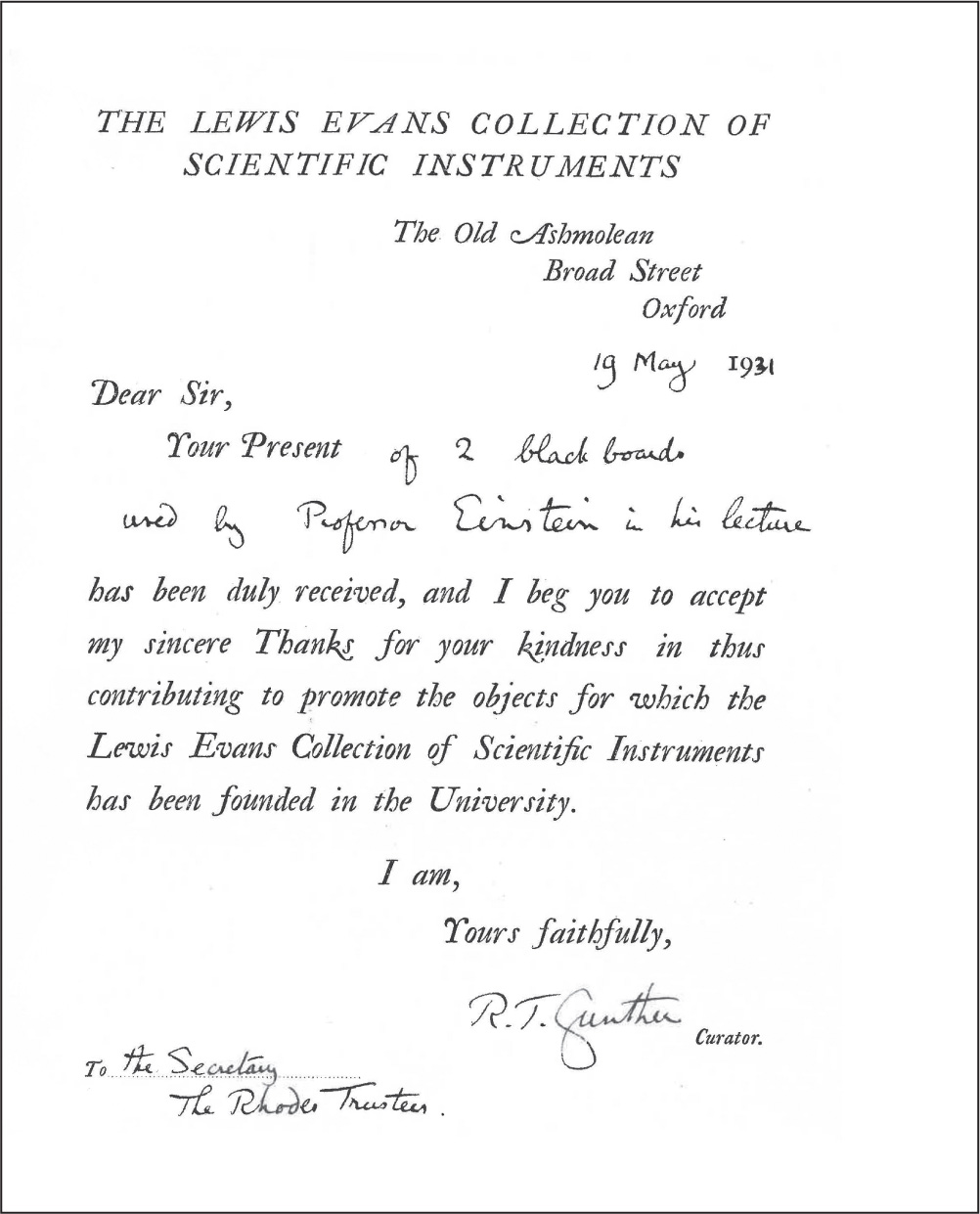

Gavin de Beer was an embryologist, who became a fellow of the Royal Society and director of the Natural History Museum in London. Robert Gunther was a historian of science, who founded the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford in 1926–30. Yet another Oxford academic involved in the rescue was Edmund Bowen, also a fellow of the Royal Society, whose laboratory work in photochemistry had confirmed some of Einstein’s theoretical work. Presumably, they were among the audience on 16 May for the second Rhodes House lecture. Certainly, on 19 May, Gunther formally thanked the secretary of the Rhodes trustees for ‘your present’ to the newly established museum ‘of two blackboards used by Professor Einstein in his lecture’. There was even a subsequent note dated 25 May from Rhodes House to Gunther, written after the third Einstein lecture: ‘I should be glad if you could come round and see the two blackboards which Einstein used on Saturday. They would normally be used again here tomorrow morning.’ But by then, it appears that Gunther felt that he had acquired sufficient written evidence of Einstein’s evanescent lectures.

One of the blackboards used by Einstein at Rhodes House, Oxford, May 1931, now kept at the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford. His calculations describe the density, size and age of the expanding cosmos, and contain a mathematical error. The blackboard was preserved by Oxford dons against the wishes of Einstein and is today the most famous object in the museum.

Letter to the Rhodes trustees from historian Robert Gunther, May 1931, thanking them for the donation of two Einstein blackboards used in his second Rhodes House lecture. Gunther was the founder of the Museum of the History of Science at Oxford. (The second blackboard was later cleaned by mistake.)

Today – whether Einstein would approve or not – one of his Rhodes House blackboards is the most famous object in Oxford’s museum, notwithstanding the museum’s collection of some 18,000 objects dating from antiquity to the twentieth century. (The second blackboard was accidentally wiped clean of Einstein’s fragile symbols in the museum’s storeroom!) It intrigues uncomprehending visitors from around the world, many of whom come specially to see it and no other object. Its mathematical symbols neatly summarise Einstein’s cosmology paper of April 1931, based on Friedmann’s relativistic model of an expanding cosmos, with the cosmological constant set at zero and Hubble’s measurements of the expanding universe used to estimate three quantities: the density of matter, the radius of the cosmos and the timespan of the cosmic expansion (given as 10,000 million years). However, its arithmetic was not totally accurate. ‘It appears that Einstein stumbled in his use of the Hubble constant,’ according to Cormac O’Raifeartaigh, ‘resulting in a density of matter that was too high by a factor of a hundred, a cosmic radius that was too low by a factor of ten, and a timespan for the expansion that was too high by a factor of ten.’ No doubt this mistake was just one of the many ‘untrue’ elements that Einstein had in mind by the time he returned to Oxford in 1933.

HONORARY DOCTORATE FROM OXFORD

By contrast with the lectures and their aftermath, the award of Einstein’s honorary doctorate was free from friction, though not without its own comedy. The ceremony took place before his third lecture on 23 May 1931 in the grandeur of the Sheldonian Theatre designed by Sir Christopher Wren, in the presence of Oxford’s vice-chancellor, Frederick Homes Dudden, a theological scholar and chaplain to King George V, and naturally in front of a packed house, at least some of whose members were by now personally known to Einstein.

Oxford’s public orator, who presented the academically attired Einstein in Latin, had perhaps the most difficult role. He was a classical scholar, A. B. Poynton, later master of University College in Oxford. ‘In so far as he understood what Relativity was about, [he] grappled manfully and ingeniously with the task of rendering it into Ancient Tongue,’ noted the Winchester College schoolboy Griffiths.

Poynton’s speech opened with a reference to the solar eclipse in late May 1919, almost exactly twelve years before, and the fact that ‘Mercurius’ (the planet Mercury) had on that occasion been observed in the position predicted by Professor Einstein. ‘Atque utinam Mercurius hodie adesset, ut, cuius est eloquentiae, vatem suum laudaret!’ (‘If Mercury were present today, he would of course praise his poet with his own eloquence!’) At the end, the public orator attempted to relate relativity to classical philo-sophy. According to a translation of the Latin published a few days later in the Oxford Times:

The doctrine which he interprets to us is, by its name and subject, interpreter of a relation between heaven and earth. It bids us view, under the aspect of our own velocity, all things that go on in space; to right and left, upward and downward, backward and forward. This doctrine does not in any way supersede the laws of physicists, but adds only the ‘momentous’ factor which they most desired. But it directly affects the highest philosophy, and it is not unwelcome to Oxford men, who have not the Euclidean temper of mind, but have learnt from Heraclitus that no man can step twice into the same river – nay, not even once; who are glad to believe that the Epicurean ‘swerve’ is not a puerile fiction; who, finally, in reading the Timaeus of Plato, have felt the want of a mathematical explanation of the universe more self-consistent and more in agreement with realities. This explanation has now been brought down to men by Prof. Albert Einstein, a brilliant ornament of our century.

Laudatory as it was, the speech contained no attempt to translate the term ‘relativity’ into Latin, no reference to gravity or electromagnetism, and not even a name check for the immortal – if Cambridge-based – Newton. (Contrast The Times in its lengthy editorial on 25 May, ‘Professor Einstein at Oxford’, which noted that ‘Like Newton, Professor Einstein is not primarily an experimental physicist, but a mathematician.’) Moreover, contrary to the speech, general relativity does ‘supersede the laws of physicists’, in the sense that it is more fundamental than Newton’s laws of motion. No wonder Einstein noted in his diary in the evening that the speech was ‘serious, but not wholly accurate’. He must have based this remark on a translation given him during the day (perhaps by Lindemann), since Einstein did not understand Latin. Yet, even when the public orator was speaking, Einstein had recognised his mention of Mercurius. ‘I had noticed his face lit up when “Mercury” was named,’ according to a friend in the audience at the Sheldonian.

She was Margaret Deneke, who had got to know Einstein soon after his arrival in Oxford. She would provide the most vivid vignettes of him among all of his contacts at the university during his visit in 1931, and subsequent visits in April–May 1932 and May–June 1933, recorded at length in her diary in translation from her frank conversations with Einstein. Not only was Deneke fluent in German, she was also intensely musical: two characteristics that immediately endeared her to Einstein.

MUSIC AND ART WITH MARGARET DENEKE

The younger of two surviving daughters of a wealthy London merchant banker born in Germany and his German-born wife who was a close friend of the celebrated pianist Clara Schumann, Margaret and her elder sister, Helena, were born in London and later moved to Oxford. In 1913, Helena was appointed bursar and tutor in German at Lady Margaret Hall, the university’s first women’s college, while Margaret became a musician/musicologist. Originally trained in the work of the great German romantic composers – Ludwig van Beethoven, Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann – she then studied modern English music under the influence of Oxford musical scholars, especially Ernest Walker and Sir Donald Tovey, and was soon interpreting English music to many school-children. Together the sisters lived in a Gothic villa named Gunfield, very close to Lady Margaret Hall, where they staged frequent performances in their music room by both famous professionals, such as Adolf Busch and Marie Soldat-Roeger, and gifted amateurs. ‘Generations of Oxford undergraduates, colleagues and friends enjoyed the Denekes’ hospitality at the many Gunfield concerts,’ according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography’s entry on Helena Deneke. ‘Marga Deneke, herself a talented pianist, was choirmaster at Lady Margaret Hall and, raising considerable sums of money through concerts and lecture recitals, became one of the college’s benefactors.’ The Oxford Chamber Music Society met at Gunfield free of charge for some twenty-seven years, with Margaret Deneke making up any deficits; especially during the Second World War, the Society owed its survival to the Deneke sisters’ generosity. In May 1931, inevitably, they would be joined by a visiting amateur violinist: Einstein.

‘In he came with short quick steps. He had a big head and a very lofty forehead, a pale face, a shock of grey, untidy hair,’ Margaret Deneke recalled of her first meeting with Einstein on 11 May. She introduced him to Marie Soldat, who was a violin virtuoso originally discovered by Brahms and a pupil of Joseph Joachim. After dinner

he turned to Mother with an engaging smile: ‘You have provided a delightful meal; now the enjoyable part of our evening is over and we must get down to work on our instruments. Shall we play Mozart? Mozart is my first love – the supremest of the supreme – for playing the great Beethoven I must make something of an effort, but playing Mozart is the most marvellous experience in the world.’

The players started with Mozart; under Marie Soldat’s rich tone on her Guarnerius del Gesu [a famous 1742 violin], the professor’s borrowed violin sounded starved and raucous, but his rhythm was impeccable. Before passing on to Haydn there was an interval for a chat. Marie Soldat commented on the professor’s long violin fingers, tapering usefully at the tips. The professor said, ‘Yes I never have practised and my playing is that sort of playing, but physical build cannot be altogether divorced from mental gifts, an unusually sensitive temperament will make its mark on a body.’

I said Adolf Busch [an intimate friend of Einstein] had got short fat fingers.

‘Well I must admit without any fingers at all no one can play a fiddle.’

Before they left, the guests signed the visitors’ book. ‘In his small clear handwriting,’ Deneke observed, Einstein wrote: ‘Albert Einstein peccavit.’

A few days later, he ‘sinned’ again. The occasion was a somewhat strained formal dinner at Rhodes House given in his honour by its warden, Wylie, the evening before Einstein’s second lecture. (Pre-dinner, poor Einstein had had to grab a needle and thread in the bachelor sleeping quarters and sew up his ill-fitting dress shirt, so that his hairy chest did not peer out during dinner.) ‘Lady Wylie thought he would enjoy himself more if music could be introduced,’ noted Deneke. ‘Professor Einstein’s English was rather halting in those days and to converse in French or German might not be too easy for the trustees.’ When the meal was finished, he, Soldat and Deneke formed a trio. According to her diary:

we were established around the piano; the trustees saw their lion disporting himself with Bach’s Double Concerto and Handel and Purcell Sonatas. He tucked the violin under his chin with a will and tuned long and loud. Then he chose the piece he wanted and made suggestions: ‘No repeats in the Adagio please and the Allegro not too fast, there are tricky bits for me.’ We started obediently and he threw himself whole-heartedly into the music. He made no effort at all to discover what the trustees might like to hear. Unashamedly we played for our own enjoyment, without the slightest pretence about performing. The trustees smoked in silence, witnessing their guest of honour having a happy evening. I doubt if they listened.

Indeed, according to Einstein’s somewhat franker diary, when their music started up, ‘The guests hastily left the room’!

How good a musician was Einstein? Opinions have varied over the decades, in both Germany and beyond (not helped by the occasional confusion of Einstein with a distinguished musicologist, Alfred Einstein, his contemporary in both Germany and the United States). Clearly Deneke had some reservations about his playing, yet she was well aware that Einstein always had to use a borrowed violin during his time in Oxford in 1931. When he returned in 1932, she recorded his advice about an instrument she was thinking of buying. ‘He scrutinised the violin with great interest, and after he had played on it he advised me not to buy it as the tone was uneven.’ Instead, he recommended, she should acquire a cheap instrument and give it to the man who had treated his own violin by adding varnish and cutting away little bits to improve the tone. ‘He had had no other violin than this treated cheap fiddle, thin in its wood, but clear in voice.’ As for the opinion of professional musicians on Einstein, it is probably summarised by the comment, ‘relatively good’, given by the pianist Artur Balsam who once played with him. Undoubtedly, Einstein was an intellectual match for professional musicians in the speed of mind essential for ensemble playing, even if he lacked their tone. At the same time, as a dedicated amateur quartet player, he was (to quote an American musicologist), ‘the denizen of dimly lit music rooms of the world where enthusiastic friends and fiddlers bend together over their instruments and sleepy children yawn, and towards the end of a long evening someone says “Let’s play some Haydn and then call it a night.”’

By no means all of Deneke’s Einstein diary for 1931–33 concerns music. She met him not only at Gunfield, but also in his rooms at Christ Church and elsewhere around Oxford, including Lady Margaret Hall, where he had agreed (somewhat reluctantly) to give a Deneke lecture named after her late father, on atomic theory. She also persuaded him to sit for a portrait by a little-known Tyrolese peasant artist, F. Rizzi, who had come to Oxford not long before Einstein’s arrival in May 1933 to do a portrait of Deneke’s mother at the family’s request. When Mrs Deneke unexpectedly died, Rizzi was left at a loose end, deprived of his main commission.

Rizzi had never heard of Einstein, but both he and his subject got on genially when Deneke brought Rizzi to Einstein’s rooms in Christ Church. On 31 May, she returned with two big bunches of flowers supplied by Lady Margaret Hall’s gardens (which were designed and looked after for decades by her sister, Helena). She noted:

Professor Einstein was still at his breakfast table and was delighted with the flowers. He had no coat on, no stockings but sandals on his bare feet. He pointed to the pile of letters and complained that correspondence was a great burden. I confirmed June 13 for the Deneke lecture and at his request made this entry in his diary. Then I asked if he would let Rizzi sketch him – we wanted work for the painter. He consented: ‘he can draw my portrait whilst I am at work; then I sit still anyhow.’ I promised Rizzi would be silent.

The following morning, she brought the artist again, installed him on some curious steps leading to the room’s main window overlooking the college’s famous cathedral, and left him alone with Einstein. Around noon, the Christ Church porter – who had been instructed to protect Professor Einstein from unscheduled visitors – phoned Gunfield to say that ‘Miss Deneke’s little man was waiting in the porch’. Immediately bicycling to Christ Church, she found Rizzi in the porch surrounded by a group of people who were admiring his profile portrait of Einstein looking down at a book. (Today it hangs in Christ Church’s Senior Common Room.) The two of them then carried it off to a photo-grapher, but all of a sudden Rizzi remembered that ‘Professor Eisenstein’, as he habitually called Einstein, had not signed the portrait. They returned to Christ Church, and found that their quarry had gone for a walk in Christ Church’s meadows. The two of them set off in hot pursuit, but Einstein had got too far ahead, and so the signature had to wait until the artist returned the next day. When Einstein finally signed the portrait in his college rooms, Rizzi told Deneke that he laughed heartily over the artist’s German aphorism: ‘Nichts koennen ist noch lange keine Moderne Kunst.’ (‘To be a Modern artist, it is not enough to lack any skills.’) Einstein’s taste in drawing, like his taste in music, was firmly in favour of the classical.

Drawing of Einstein by F. Rizzi, a little-known Tyrolese peasant artist, produced in Einstein’s rooms at Christ Church during his third visit to Oxford, in 1933. It is now on display in the college’s Senior Common Room.

VISITOR AT CHRIST CHURCH

Christ Church’s relationship with Einstein proved amiable but eccentric from beginning to end. The dinner-jacketed and gowned Christ Church dons were ‘the holy brotherhood in tails’ (‘der heiligen Brüderschaar im Frack’), noted a wryly amused Einstein in his diary. He always disliked having to wear formal dress – and even, famously, socks – whether he was in Germany, England, the United States or any other country. ‘He was by nature a rebel who enjoyed being unconventional,’ wrote his Oxford-educated scientific collaborator in Princeton, Banesh Hoffmann. ‘Whenever possible he dressed for comfort, not for looks.’ Einstein regarded such formalities as part of the German Zwang (‘compulsion’ or ‘coercion’) that he resisted throughout his life, from childhood onwards. One of the Christ Church dons, the economist Sir Roy Harrod (whom we encountered in 1919 as an undergraduate interested in relativity), later remarked of their famous visitor: ‘In our governing body I sat next to him; we had a green baize table-cloth; under cover of this he held a wad of paper on his knee, and I observed that all through our meetings his pencil was in incessant progress, covering sheet after sheet with equations.’ Another don, Gilbert Murray (who had befriended Einstein while serving on the League of Nations Committee on Intellectual Cooperation in the 1920s), remembered coming across the political refugee Einstein in 1933 sitting alone in the college’s grand Tom Quad with a smiling, faraway look on his face. ‘Dr. Einstein, do tell me what you are thinking.’ Einstein replied: ‘We must remember that this is a very small star, and probably some of the larger and more important stars may be very virtuous and happy.’

Appropriately enough, Einstein’s first set of Christ Church rooms, overlooking Tom Quad, had been occupied in the later nineteenth century by the mathematician (and clergyman) Charles Lutwidge Dodgson – better known as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and, of course, the poem which inspired ‘The Einstein and the Eddington’ quoted earlier. By 1931, the rooms were home to a war veteran and classical scholar, Robert Hamilton Dundas, who was away from England on a world tour in 1930–31, luckily for Einstein. When Dundas returned, he was charmed to find that Einstein had written a poem of his own in the visitors’ book. More doggerel than Carroll, it is nonetheless quite thoughtful and witty, in this free translation from Einstein’s rhymed German by an Oxford literary scholar, J. B. Leishman:

While he lingers far away,

Drinking wisdom at the source

Where the sun begins its course.

That his walls may not grow cold

He’s installed a hermit old,

One who undeterredly preaches

What the art of Numbers teaches.

Shelves of towering folios

Meditate in solemn rows;

Find it strange that one can dwell

Here without their aid so well.

Grumble: Why’s this creature staying

With his pipe and piano playing?

Why should this barbarian roam?

Could he not have stopped at home?

Often, though, his thoughts will stray

To the owner far away,

Hoping one day face to face

To behold him in this place.

A year later, Einstein and Dundas – the ‘barbarian’ and his bibliophile host – did meet, when Einstein returned to Christ Church in 1932. The poem was published in The Times soon after Einstein’s death, and in due course the visitors’ book was donated to the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Einstein’s joke against himself refers to perhaps his only serious reservation about Christ Church (and in fact the university as a whole): its penchant for formality, symbolised by the dreaded dinner-jacket. His two earliest diary entries after arrival in the college with Lindemann catch the flavour well. ‘Evening club meal in dinner-jacket. The apartment is reminiscent of a small fortress and belongs to a philologist who is currently in India. Young servant; communication droll,’ he noted on 1 May. ‘The dinner takes place with about 500 professors and students, the former all in dinner-jackets and black gowns, a bizarre as well as boring affair. Of course the service is men only. One gets a slight idea of how horrible life would be without women. All in a kind of art basilica!’ (Today Christ Church’s dining-hall displays Einstein in a stained-glass window.) And in his next, briefer entry on 2/3 May he wrote: ‘Silent existence in the hermitage in bitter cold. In the evening the solemn Communion Supper of the holy brotherhood in tails. On 3 May with deans (clergymen), who introduce me as a quasi-guest, taciturn and solemn but benevolent with delicate jokes on the tips of their tongues.’ Among them was of course Dean White, who would later fall asleep at Einstein’s third, and toughest, Rhodes lecture.

Lindemann, and some other Christ Church colleagues, notably Harrod and Murray, compensated for the overall atmosphere of formality. Einstein ‘was a charming person, and we entered into relations of easy intimacy with him,’ Harrod recalled. ‘He divided his time between his mathematics and playing his violin; as one crossed the quad, one was privileged to hear the strains coming from his rooms.’ (Like Lindemann, however, Harrod thought Einstein ‘naïve’ in human affairs.) Furthermore, over time Einstein himself came to appreciate somewhat better the college’s English reserve, if not so much its clerical aura. On the whole, though, Einstein’s most fruitful contacts in Oxford took place less in Christ Church than in other settings, ranging from other colleges and university societies to private houses and more informal meetings – including, of course, the dinner-concerts at Gunfield organised by Deneke.

Einstein in conversation, possibly in German, somewhere in Oxford, probably in 1931. The man on the right might be Hermann Fiedler, professor of the German language and literature at Oxford, who according to Einstein’s diary went for walks in the city with him. The man in the middle might be Frederick Lindemann, professor of experimental philosophy (physics) at Oxford, Einstein’s host at the university, who was later the chief scientific adviser to Winston Churchill. If so, this ‘mystery’ picture is the only British photograph of Einstein with Lindemann, who disliked being photographed.

PHYSICS, PACIFISM, SPORTS AND WANDERING IN OXFORD

Some of these encounters naturally concerned physics and mathematics. Einstein ‘threw himself into all the activities of Oxford science, attended the colloquiums and meetings for discussions and proved so stimulating and thought provoking that I am sure his visit will leave a permanent mark on the progress of our subject’, Lindemann wrote in June 1931, after Einstein’s departure. ‘Combined with his attractive personality, his kindness and sympathy have endeared him to all of us and I have hopes that his period as Rhodes lecturer may initiate more permanent connections with this university which can only prove fertile and advantageous in every respect.’

Admittedly, Lindemann addressed this encomium of Einstein to Lothian at the Rhodes Trust, probably with an eye on future funding for him in Oxford. Nevertheless, Lindemann’s comments were essentially true concerning Einstein’s attitude. What they overlooked, however, was the fundamentally experimental orientation of Oxford science in 1931, which included hardly any theoreticians capable of discussing physics and mathematics at Einstein’s level. There was to be no Oxford equivalent for Einstein of Cambridge’s Sir Arthur Eddington.

Thus, Einstein’s dinner at New College with John Sealy Townsend, Wykeham Professor of Physics, led nowhere, other than a visit to the college chapel for a fine performance of Mozart’s Requiem and a tour of Townsend’s laboratory. And a lunch at Wadham College with the eminent pure mathematician G. H. (Godfrey Harold) Hardy, author of A Mathematician’s Apology, was noteworthy only for Hardy’s showing Einstein an interesting game with matches. The most promising candidate for a serious discussion was a cosmologist, Edward Arthur Milne, who had been appointed the first Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics at Oxford in 1929. On 5 May 1931, Einstein attended a meeting with Milne at Trinity College, during which Milne gave a speech on novae (new stars) to a small group. He is a ‘very clever man’, Einstein noted in his diary. The following day Milne had further discussions with Einstein in the company of Lindemann, and another meeting with Einstein the day after that. But when Milne went on during 1932 to develop a theory of ‘kinematical relativity’ based on his conviction that general relativity was unsound, which aimed to derive cosmological models by extending the kinematical principles of special relativity, Einstein regarded this approach as unsound. Einstein’s doubts were confirmed by two independent analyses in 1935 and 1936, which ‘showed that Milne’s distinctive approach led, ironically, to the same set of basic models already studied in relativistic cosmology’, noted The Cambridge Companion to Einstein.

Next to physics and music, Einstein’s other preoccupation in Oxford was political, on each of his three visits. For example, on 22 May he visited Ruskin College, an independent institution set up as Ruskin Hall in 1899 with the support of the trades union movement to offer courses for working-class students unable to gain access to the University of Oxford. Ruskin students were permitted to attend the university’s lectures, however. Having met its forty or so young men and women, Einstein pronounced Ruskin an ‘excellent institution’, and noted that nineteen British Members of Parliament were former members of Ruskin.

He also had meetings with political activists from both inside and outside the university. On 20 May, for example, he attended the League of Nations Society, and answered questions for two hours on internal German and Russian affairs. And on 23 May, on the evening of the day of his doctoral ceremony, he met pacifist university students at a private house, and was impressed by their political maturity – especially as compared with their ‘pitiful’ German equivalents in Berlin.

Another meeting on 26 May, with some members of War Resisters’ International under its chairman, the British member of parliament A. Fenner Brockway – who had served time in prison during the First World War for his anti-conscription activities – brought forth a categorical response from Einstein, recorded by Brockway. He exclaimed: ‘There are so many fictitious peace societies. They are prepared to speak of peace in time of peace, but they are not dependable in time of war. Advocates of peace who are not prepared to stand for peace in time of war are useless. To advocate peace and then to flinch when the test comes means nothing – absolutely nothing.’ Surely this was a statement Einstein would come to regret in 1933.

A final meeting, with the Quaker-run Friends’ Peace Committee on 27 May 1931, was probably the most revealing of all about Einstein’s pacifist views. A report of it in The Friend opened with a reference to his recent controversial ‘Two-per-cent speech’ in the United States, and discussed his views of how to organise war resistance in countries without conscription (such as post-war Britain), and also how to promote peace internationally. ‘For example, he suggested that it is very important to organise the churches and get declarations from them against participation in war’, in particular the Roman Catholic Church, ‘as this would have so much influence in France and Italy.’ As for diminishing Germany’s rising militancy, Einstein advised that pacifist endeavours to denounce the war guilt clause in the Versailles peace treaty were less likely to work than international efforts to relieve Germany’s ‘terrible economic depression’ by finding a solution to its war reparations problem. But he was not optimistic when asked about the prevention of war by international diplomacy, no doubt because of his experiences with the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation. ‘He pointed out that the machinery is there in the League of Nations, but that unfortunately in his view it is too weak. He believes, however, that the machinery is capable of being made strong and effective. “That depends,” he said, “on what the people will.”’ Apropos, Einstein paid this unexpected tribute to religion:

To Friends, perhaps the most interesting part of the interview was Professor Einstein’s statement that his attitude to war was held because he can ‘do no other.’ He agreed that the strongest anti-war convictions are those with a religious basis. People may be convinced intellectually that war is futile, but that is not enough. This greatest of thinkers does not trust to the intellect alone. ‘Reason,’ he says, ‘is a factor of secondary importance.’

Yet it would be untrue to leave the impression that all of Einstein’s time in Oxford during May 1931 was taken up with scientific, musical and political activities. As his diary made plain, albeit often laconically, he had a varied range of other experiences.

For example, a physics research student at Christ Church, Douglas Roaf, hearing of Einstein’s love of sailing, took him out on the River Thames in a skiff down to the Abingdon Cut. Seeing that Roaf was properly attired for the occasion and wearing plimsolls, Einstein offered to take off his brown boots. He also saw at first hand the sporty side of Lindemann, who had been a championship tennis player in both Germany and England in his younger days. While Lindemann played squash on a private squash court, Einstein watched from the spectators’ gallery, as the mysteries of the game were explained to him by one of his undergraduate friends at Christ Church, Alfred Ubbelohde (later professor of thermodynamics at Imperial College in London). On another occasion, having attended a university regatta by the river in the afternoon, Einstein went to an extraordinary lecture in the university church about old Coptic music. He noted that the (unnamed) lecturer – ‘a fat giant with a red face’, standing in a blue habit on a blue podium – was ‘a picturesque swindler’. More productively, he visited the Ashmolean Museum with Lindemann to see the famous objects excavated from the Minoan civilisation in Crete by Sir Arthur Evans. They struck Einstein as ‘more Egyptian than Greek in character’.

In addition, he enjoyed plenty of informally dressed walking in Oxford, either with others – including Hermann Fiedler, the professor of the German language and literature – or, quite frequently, wandering on his own in the streets and parks. As he told Deneke: ‘The types of humanity in the streets here are interesting to me – they are quite unlike those seen at home.’ And he was taken out of Oxford by car into the Cotswold countryside, the beauty of which he much appreciated. Lindemann introduced him to his eighty-five-year-old father at his country house in the Thames Valley, who impressed Einstein with his liveliness. Adolph Lindemann, besides being an amateur astronomer keenly interested in relativity, had been an engineer and businessman making ships for the Russian navy under the tsars. He spoke of corruption in Russia. Having delivered ten ships, he was paid for nine of them. When he asked the government official in charge of the purchase about payment for the tenth ship, the official replied: ‘Make sure you get home as soon as possible.’ At another country house, belonging to a friend of Lindemann, old Lady Fitzgerald, Einstein was tickled to see a strange, new, technological advance: drinking fountains for cows. When a cow pressed her muzzle against a metal plate, a valve opened and the water flowed into a drinking bowl. ‘Soon there will be water-closets for cows,’ mused Einstein, the former patent clerk, in his diary. ‘Long live civilisation!’

Not recorded in the diary was his brief flirtation with a woman who had followed him from Germany to Oxford. In total contrast to the musical Margaret Deneke, Ethel Michanowski was a Berlin socialite. Einstein composed a brief poem for her on a notecard from Christ Church, which began: ‘Long-branched and delicately strung, / Nothing that will escape her gaze’. Michanowski then sent him an expensive present, which he did not welcome. ‘The small package really angered me,’ he wrote. ‘You have to stop sending me presents incessantly. . . . And to send something like that to an English college where we are surrounded by senseless affluence anyway!’

But probably the most evocative memory of Einstein in Oxford concerned simply his charisma. It was recalled in an account of a chance encounter by William Golding, the future author of Lord of the Flies and Nobel laureate, who started as an undergraduate in science and then changed to literature. Sometime in 1931, Golding happened to be standing on a small bridge in Magdalen Deer Park looking at the river when a ‘tiny moustached and hatted figure’ joined him. ‘Professor Einstein knew no English at that time, and I knew only two words of German. I beamed at him, trying wordlessly to convey by my bearing all the affection and respect that the English felt for him.’ For about five minutes the two of them stood side by side. At last, said Golding, ‘With true greatness, Professor Einstein realised that any contact was better than none.’ He pointed to a trout wavering in midstream. ‘Fisch,’ he said. ‘Desperately I sought for some sign by which I might convey that I, too, revered pure reason. I nodded vehemently. In a brilliant flash I used up half my German vocabulary: ‘Fisch. Ja. Ja.’ I would have given my Greek and Latin and French and a good slice of my English for enough German to communicate. But we were divided; he was as inscrutable as my headmaster.’ For another five minutes, the unknown undergraduate Englishman and the world-famous German scientist stood together. ‘Then Professor Einstein, his whole figure still conveying goodwill and amiability, drifted away out of sight.’

Einstein in Oxford during one of his three visits in 1931, 1932 and 1933. He liked to stroll around the city on his own, comparing its life with that of Berlin. The precise location is unknown.

ELECTED ‘STUDENT’ OF CHRIST CHURCH

Even before Einstein left Oxford on 28 May 1931, Lindemann appears to have begun negotiations within Christ Church to lure him back. His idea was that Einstein should be elected a ‘research student’ (i.e. a fellow) of the college and be offered a bursary from college funds so that he could spend relatively brief periods of time in Oxford each year at his own convenience. By late June, Dean White of Christ Church informed Lindemann that the college was in a position to offer a ‘studentship’ to Einstein for five years, with an annual stipend of £400, a dining allowance and accommodation during his periods of residence, which it was hoped would last for about a month each year during Oxford term time. Lindemann promptly intimated this possibility to Einstein in a letter.

Einstein was immediately tempted – not least because of the disastrous economic and political situation in Germany, with banks at risk of collapse, escalating unemployment and the rising popular appeal of the Nazi Party. ‘Your kind letter has filled me with great pleasure and brought back to me the memory of the wonderful weeks in Oxford,’ he wrote to Lindemann on 6 July. However, he went on to advise Lindemann of a difficulty that had put him ‘on the horns of a dilemma’: whether to accept Christ Church’s offer or a parallel offer from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, since he was unable to fulfil both obligations given his commitments in Berlin. He therefore proposed the following course of action: that Lindemann write immediately to the dean of Christ Church asking him not to send his invitation to Einstein yet. ‘I should not like either to delay replying to him or to have to answer in the negative.’ Better, he said, first to await the answer from Pasadena and then he would take a decision on what he should do.

By mid-July, it became clear that Einstein was ready to accept Christ Church’s offer. But in a letter to the dean he did not clarify whether he accepted all of the terms of the studentship, in particular its annual residence requirement. Lindemann persuaded the college to give Einstein the benefit of the doubt: although he might spend less than a month at Christ Church in any one year, he would make up for this during another year. On 21 October, the governing body elected Einstein unanimously to a research studentship. Einstein accepted the offer on 29 October with a warm letter to the dean referring to the college’s ‘harmonious community life’.

In the interval, however, Dean White received a stern letter of protest at the college’s decision. Dated 24 October, it came from a former tutor and student of Christ Church who had taught classical history there from 1900 to 1927, before migrating to Brasenose College when he became Camden Professor of Ancient History: John George Clark Anderson. He began:

Dear Dean, I was amazed to read the announcement of your latest election to a research studentship, and I hope that, in view of my long connection with Christ Church, to which I gave the best years of my life, and my part in framing the new statutes, particularly those relating to research, you will not resent my writing a line to you about it. My only concern is that Christ Church should always appear to do the right thing.

According to Anderson, ‘I am sure it never occurred to the mind of anyone concerned with the new statutes that there was any possibility of emoluments being bestowed on people of non-British nationality. The old statutes were, I think, explicit about British nationality as a qualification for election to studentships . . .’. He continued: ‘I cannot help thinking that it is unfortunate that an Oxford college should send money out of the country in the present financial situation and at a time when the university is receiving a large government grant at the expense of the taxpayers for educational purposes. The more I think of it, the more strange does this new development appear to me . . .’. And he concluded: ‘Forgive me if I intrude: I have no wish to do that. I have written only as a loyal member of the House [Christ Church], who has its welfare at heart.’

At no point in Anderson’s letter did he mention Einstein by name or give even the merest hint that he was aware of Einstein’s eminence. The dean took up this point in his reply:

I think that in electing Einstein we are securing for our society perhaps the greatest authority in the world on physical science; his attainments and reputation are so high that they transcend national boundaries, and any university in the world ought to be proud of having him. Then in spite of his scientific position he is a poor man, and this quite moderate pecuniary help will enable him to carry on his work better.

In answer to Anderson’s other points, the dean wrote:

I do not quite follow your argument about our statutes, and persons of non-British nationality; and of course I was never here under the old statutes. But it seems to me that the only possible reason for deleting the restriction must have been the wish to widen the area of selection. If the college wished to exclude foreigners, why did it not say so?

It is quite true that we are paying money out of England; but I think we are getting more than our money’s worth.

A further letter from Anderson expanded at length on his arguments about funding, some of which were reasonable, especially in a time of serious economic depression. Yet, the emotions underlying the arguments were clear from two comments: that a research studentship should not go to ‘a German who has no connection with the university (beyond being the recipient of an honorary degree)’; and that ‘it does not seem to me to be patriotic, especially in such times as the present, to use college revenues to endow foreigners. Charity should always begin at home.’ Anti-German feeling and Oxford academic parochialism were still, sadly, alive and well in 1931. To the credit of Christ Church, its governing body rose above such attitudes with Einstein, well before he became a target of Nazi attacks in 1933.

Amusingly, even though the British tax authorities agreed with Anderson’s argument about money going out of England, they did not accept the negative conclusion he drew from it. In 1932, a zealous Oxford tax inspector suggested that Einstein’s Christ Church stipend should be liable for income tax. A concerned Lindemann discussed the matter with the chairman of the board of the Inland Revenue, Sir James Grigg, and the Revenue’s special expert on the subject, a certain W. G. E. Burnett. According to Burnett, Einstein’s annual stipend from Christ Church should be exempt from British tax. Einstein did not live or work in Oxford, he wrote, and thus ‘The world at large, and not Christ Church in particular, gets the benefit of his work.’ Although England would get its money’s worth from Einstein’s visits to Oxford, his true value would have no national boundaries.