Science is not and never will be a closed book. Every important advance brings new questions. Every development reveals, in the long run, new and deeper difficulties.

Comment by Einstein in The Evolution of Physics: The Growth of Ideas from the Early Concepts to Relativity and Quanta, 1938

Even as he crossed the Atlantic Ocean in October 1933, Einstein busied himself with trying to help other refugees from Nazi Germany. Writing to the Academic Assistance Council in London on 14 October from on board ship to express his satisfaction at the Albert Hall event and the substantial funds it had raised, he brought to the council’s attention the names and details of three deserving Jewish academics: a professor of paediatrics now in Holland, a psychiatrist still in Berlin and a physician in Zurich. The psychiatrist, Otto Juliusburger – a friend who had treated Einstein’s nephew – wanted to emigrate to Palestine and found a clinic there, Einstein noted, but he had been financially ruined by the German government. If the council were to contact him, he added, it should on no account mention who had suggested Juliusburger’s name, because this move would be highly dangerous for him if he were somehow associated with Einstein. (Juliusburger eventually left Berlin at the last minute, in 1941, with Einstein’s help and financial support, and died in New York in 1952 at an advanced age.)

About a month after he reached Princeton, he wrote again to Lindemann on the same subject. It was ‘hardly justifiable’, he said, that he should continue to receive payments from Christ Church, given the current emergency. Might the college offer the money from his annual stipend – £400 per annum for the years 1932–37 – to another foreign scholar in distress?

Lindemann replied on 6 December, after discussion with some colleagues, that such an arrangement would probably be possible. ‘On the other hand, we should be very sorry if you abandoned your connections with the college.’ He hoped that Einstein would come to stay in Oxford for as long as possible during the summer of 1934, ‘especially since Belgium cannot be particularly attractive in the present circumstances’. Then he added, obviously thinking of what he regarded as Einstein’s political naïveté (including perhaps the speech at the Albert Hall?):

I trust you are enjoying America and have not been pestered too much by people who want to exploit you for political ends. I gather in Germany scarcely any of these demonstrations do any good. On the contrary, any activities abroad are made an excuse to intensify the campaign against the Jews remaining. In these matters politicians, even the most well meaning, unless they know the situation in Germany, are apt to be unsafe guides to follow.

Einstein replied quickly, but made no commitment to visit Oxford during the following year. As for politics in the United States, he wrote: ‘I have voiced my opinion much less than it may seem, since the press makes a great deal of fuss over me without my intending it or wishing it.’ But then he significantly qualified this observation: ‘All the same I am of the opinion that a conscientious person who has a certain amount of influence cannot in times like the present keep completely silent, since such silence can lead to wrong interpretation which is undesirable in the present circumstances.’

Here was a hint of what would keep Einstein from returning to Europe. If the American press oppressed him, how much more oppressive would be the European press, given his uniquely symbolic role in opposing the increasing barbarity of Nazism? While he could cope with one Albert Hall meeting, a series of such events would have been a very different and much more stressful matter. Nor would he have a hideaway to retreat to and think about science, away from the pressure of political and media events; an Oxford college, even Christ Church, was far from being such a retreat. So he declined offers of hospitality in England in mid-1934 from both Lindemann and, separately, Locker-Lampson, who was equally keen on Einstein’s return for his own, entirely non-scientific reasons.

Nothing came of Lindemann’s hopes for another Einstein visit to Oxford. In early May, Einstein officially informed the dean of Christ Church that he would not visit the college that summer and hoped that his stipend might be used in whole or in part to pay one or more distinguished foreign scientists to give brief lecture courses during the term. If this suggestion were agreeable, then the dean might consult Lindemann, and also Erwin Schrödinger, who was then in Oxford, to find out which scientists were available. ‘I need scarcely tell you how much I regret my inability to see once more my many friends at Christ Church but I hope to be more fortunate on some future occasion.’ And in January 1935, he told Lindemann that he would not visit that year either, ‘because if I come to Oxford I must also go to Paris and Madrid and I lack the courage to undertake all this’. He said almost the same thing, around the same time, to his musical friend Elisabeth, Queen of Belgium: ‘Sometimes I think back nostalgically to beautiful past hours; they tempt me to make a journey to Europe. But so many obligations would await me there that I cannot summon the courage for such an undertaking.’ No doubt, in addition to the demands of anti-Nazi politics, Einstein also had in mind his reluctance to deal with intractable family matters in Europe, in particular the psychiatric illness of his younger son, Eduard, looked after by his ex-wife Mileva. He did not accompany his wife Elsa when she returned to Paris in May 1934 to watch her elder daughter, Ilse, die – despite his fondness for his stepdaughter.

ESTABLISHMENT AT PRINCETON AMONG FELLOW EUROPEAN EXILES

Thus did Einstein’s last institutional link with England, and with Europe as a whole, fade away. But at the same time, of course, Europe came to Einstein in America, in the shape of numerous Jewish fellow refugees and non-Jewish visitors to the Institute for Advanced Study. In fact, Einstein’s closest human interactions in America were almost exclusively with Europeans, not native-born Americans, until his death in 1955. As noted by an influential English-born physicist, Freeman Dyson, who knew Einstein at Princeton in 1948 and later settled in the United States: ‘He had gone through the ritual of naturalisation, but he remained an alien spirit in America.’ In fact, Einstein retained his Swiss citizenship when he became a United States citizen in 1940. Despite his admiration for the principles of American democracy, Dyson’s summary comment feels true. After all, in late 1939, following the outbreak of war in Europe, Princeton University’s freshmen chose Hitler, for the second year running, as ‘the greatest living person’ in the annual poll of their class conducted by the Daily Princetonian. (The German leader received ninety-three votes in the poll; Einstein twenty-seven votes; and Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, fifteen votes.) Certainly, Einstein never gave expression to any deep gratitude, or even love, towards America, as he did towards England in 1933.

By way of example of his continuing European Jewish affiliations, he collaborated with Leopold Infeld and Banesh Hoffmann on general relativity, to create the important Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations of motion, published in 1938. Infeld was a Polish-born physicist who left Poland for Cambridge in 1933, and later came to Princeton as a Polish refugee without any academic position, where his excellent command of English enabled him to co-write The Evolution of Physics with Einstein and survive financially on the royalties from sales of the book. Hoffmann was a British-born son of Polish immigrants, educated at the University of Oxford, who earned his doctorate at Princeton University, settled at the City University of New York as a mathematician, and later wrote Albert Einstein: Creator and Rebel with Einstein’s secretary, Dukas.

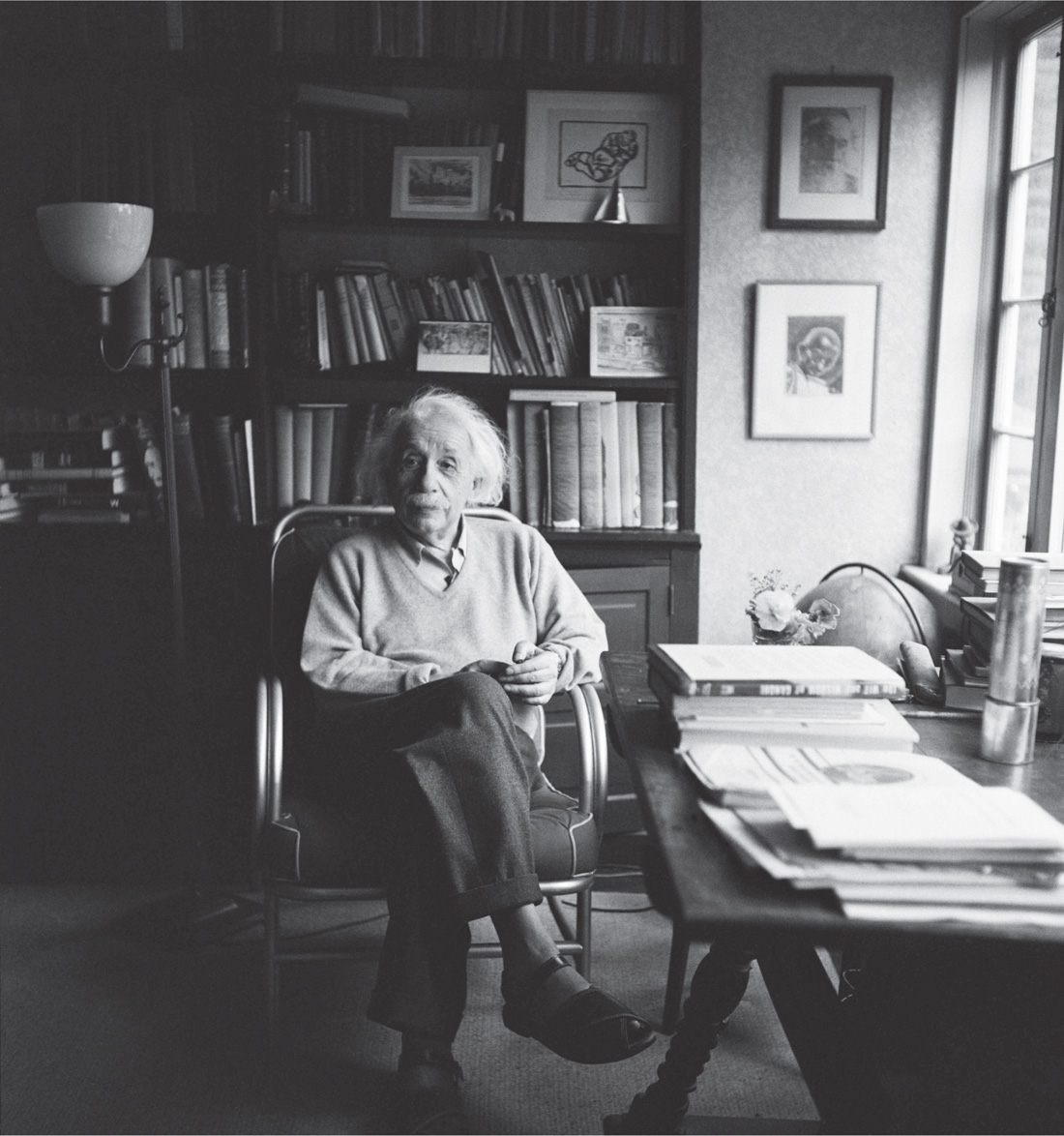

Einstein in his study at Princeton, 1951. On the wall is a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi, of whom Einstein said: ‘Generations to come, it may well be, will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth.’ Other walls carried portraits of Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell. Much of Einstein’s time in Princeton was spent alone at home, working on physics, despite his active involvement with American Cold War politics.

Hoffmann had an irresistible anecdote about Einstein in Princeton caught in the act of thinking about physics, accompanied by Infeld and himself:

Whenever we came to an impasse the three of us had heated discussions – in English for my benefit, because my German was not too fluent – but when the argument became really intricate Einstein, without realising it, would lapse into German. He thought more readily in his native tongue. Infeld would join him in that tongue, while I struggled so hard to follow what was being said that I rarely had time to interject a remark till the excitement died down.

When it became clear, as it often did, that even resorting to German did not solve the problem, we would all pause, and then Einstein would stand up quietly and say, in his quaint English, ‘I vill a little t’ink’. So saying he would pace up and down or walk around in circles, all the time twirling a lock of his long, greying hair around his forefinger. At these moments of high drama Infeld and I would remain completely still, not daring to move or make a sound, lest we interrupt his train of thought. A minute would pass in this way and another, and Infeld and I would eye each other silently while Einstein continued pacing and all the time twirling his hair. There was a dreamy, far-away, and yet sort of inward look on his face. There was no appearance at all of intense concentration. Another minute would pass and another, and then all of a sudden Einstein would visibly relax and a smile would light up his face. No longer did he pace and twirl his hair. He seemed to come back to his surroundings and to notice us once more, and then he would tell us the solution to the problem and almost always the solution worked.

So here we were, with the magic performed triumphantly and the solution sometimes was so simple we could have kicked ourselves for not having been able to think of it by ourselves. But that magic was performed invisibly in the recesses of Einstein’s mind, by a process that we could not fathom. From this point of view the whole thing was completely frustrating. But, from the more immediately practical point of view, it was just the opposite, since it opened a way to further progress and without it we should never have been able to bring the research to a successful conclusion.

As Infeld subsequently observed: ‘The clue to the understanding of Einstein’s role in science lies in his loneliness and aloofness. In this respect he differs from all other scientists I know.’ Perhaps Dirac, whom Infeld knew in Cambridge, could be regarded as ‘the nearest to Einstein, although the difference between them is still great’.

NUCLEAR FISSION AND THE ATOMIC BOMB

Probably the best-known European Jewish refugee to work with Einstein in America was the Hungarian-born physicist Leo Szilard. Having moved from post-war Hungary to study in Berlin, he got to know Einstein in the early 1920s and together they designed and patented an Einstein–-Szilard refrigerator pump in 1927, which was later used for the circulation of liquid sodium coolant in nuclear reactors. With the advent of the Nazi regime, Szilard moved to England in 1933, became involved with the fledgling Academic Assistance Council, and took a job at St Bartholomew’s Hospital studying the use of radioactive istopes for medical treatments. While in London – after reading a newspaper article on atomic energy by Rutherford and supposedly just after waiting for a traffic light not far from the British Museum to go green so that he could step off the kerb – Szilard conceived, on 12 September 1933, the idea of the nuclear chain reaction, which would prove so crucial in the atomic bomb project. In 1938, fearing an imminent war with Germany, he emigrated to the United States, where he once again came in contact with Einstein.

In July 1939, Szilard became concerned by reports that German physicists were investigating nuclear fission, very likely with a view to making a bomb. He – accompanied by another Hungarian émigré physicist, Eugene Wigner, a future Nobel laureate – decided to drive out from New York and interrupt Einstein at his summer house in rural Long Island, in order to ask him to intervene politically. It was so tricky to find the address in Peconic, however, that they were about to give up and return to New York when Szilard thought of asking a young boy where Professor Einstein lived. The boy got into their car and took them to him.

Talking to Einstein, Szilard was surprised to discover that he had not considered the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction. That is, the idea of one neutron bombarding a uranium atom, causing it to fission and release two neutrons, which then cause two uranium atoms to fission, producing four neutrons, and so on – and very quickly a concatenation of neutrons and an explosion of atomic energy. ‘I never thought of that!’ Szilard recalled Einstein’s saying when he told him that Enrico Fermi (a recent physicist refugee from Mussolini’s Italy) had just achieved a nuclear chain reaction in his New York laboratory. But as usual Einstein was quick to see the scientific implications of the new idea. And he instinctively shared his visitors’ fear that the Nazis might build the bomb first. ‘He was willing to assume responsibility for sounding the alarm even though it was quite possible that the alarm might prove to be a false alarm,’ said Szilard. ‘The one thing most scientists are really afraid of is to make fools of themselves. Einstein was free from such a fear and this above all is what made his position unique on this occasion.’

By 2 August, the threesome had finalised what would become a historic letter from Einstein to President Franklin Roosevelt. Its most dramatic paragraph read as follows:

This new phenomenon [a nuclear chain reaction] would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable – though much less certain – that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.

But Einstein advised that such bombs might possibly turn out to be too heavy to be transported in aircraft.

Einstein’s letter was personally delivered to the president through a trusted intermediary after a considerable delay – by which time war had broken out in Europe. Roosevelt responded promptly, but it took well over two years (and another reminder to Roosevelt from Einstein in 1940), plus the Japanese attack on the United States in December 1941, before the Manhattan Project to build the bomb got fully under way.

At this time, during 1941, Infeld – who had now emigrated from the United States to Canada – happened to publish an autobiography, Quest. He wrote presciently: ‘Very few of the younger generation of physicists are seriously interested in the problems with which Einstein occupies his life. Most of them work in close contact, gathering material, searching for theories, often of a provisional character, to fit the tremendous richness of experimental data in the realm of nuclear physics’ – a situation that did not remotely resemble that of solitary young physicist-cum-lighthouse-keepers as fantasised by Einstein in his Albert Hall speech in 1933.

Indeed, Einstein had nothing directly to do with the actual making of the atomic bomb – unlike Szilard and Wigner, who both joined the Manhattan Project. While he was responsible for deriving the equation E = mc2, which he published in 1905, at that time he had absolutely no vision of its use in weaponry. ‘It is true that this equation plays an important role in nuclear physics, but to say this made possible the construction of weapons is like saying that the invention of the alphabet caused the Bible to be written,’ remarked Abraham Pais. In July 1939, when Szilard met him, Einstein was clearly out of touch with nuclear physics. Despite his letters to Roosevelt, during the Manhattan Project in 1942–45 Einstein was not given a security clearance by the army authorities (probably because of his alleged Communist sympathies) – although he did receive clearance from the naval authorities to work on the theory of explosions – and was kept officially unaware of the project’s technical progress right up to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. So Einstein was certainly not the ‘father’ of the atomic bomb, as strongly implied on a famous cover of Time magazine in 1946, although there is a case for calling him the bomb’s ‘grandfather’. But after 1945, once he came to know that the German scientists (including Heisenberg) had achieved no significant progress in building an atomic bomb, Einstein strongly regretted his encouragement of Roosevelt; and for the remainder of his life he was relentlessly opposed to the spread of nuclear weapons.

As well as receiving visitors from Europe, Einstein also kept in contact by letter with those who remained there. His correspondents included Elisabeth, Queen of Belgium, Murray in Oxford, two old friends from Zurich days, Besso and Solovine, and among the major physicists living outside the Third Reich, Born in Britain (Cambridge and Edinburgh) and Schrödinger in Ireland (Dublin).

FRIENDSHIP AND DEBATE WITH MAX BORN ACROSS THE ATLANTIC

The most illuminating of these exchanges was undoubtedly that with Born – most famously, Einstein’s 1926 remark to Born about God not playing dice with the universe – covering the period 1916–55, beginning in wartime Germany and continuing after the last personal meeting between Einstein and Born in 1932. Thereafter, they were divided by the Atlantic Ocean. (Born arrived in England in 1933 just after Einstein’s departure, and never visited the United States after 1933.) Like Einstein, Born abandoned his German citizenship, becoming a British citizen just days before the outbreak of war in 1939, in Edinburgh, where he had been appointed a professor of physics at the uni-versity in 1936. His son and two daughters married and settled down in the new country. But unlike Einstein, Born returned to Germany in 1954 on his retirement, and died in his native land. Their letters range from analysis of quantum mechanics to debate over the German threat to peace, including some fundamental disagreements about physics, politics and life in general, which at times led to long periods of silence between them. Nonetheless, Born, who edited the letters after Einstein’s death with the addition of an extensive commentary, concluded the collection with the comment: ‘With his death, we, my wife and I, lost our dearest friend.’

It was published after Born’s own death as The Born–Einstein Letters in 1971, with prefatory material by two Nobel laureates: a foreword by Bertrand Russell and an introduction by Heisenberg, both of whom had known Born and Einstein personally, if from very different angles. Then it appeared in a second edition in 2005, the centenary of special relativity, with a new preface jointly written by Diana Kormos Buchwald, general editor of the Einstein Papers Project, and Kip Thorne, a leading expert on the astrophysical implications of general relativity. They focused on the history of Einstein’s scientific ideas over a century, and how ‘many of his scientific concerns at the time continue to engage modern physics’. For instance, the Einstein–Infeld–Hoffmann equations of 1938 – ‘Einstein’s greatest contribution to relativity after 1920’ – and also gravitational waves, predicted by Einstein from general relativity in 1916, which were finally confirmed to exist in 2016 by a team including Thorne (for which he shared a Nobel prize in 2017).

To quote Russell’s foreword about Born and Einstein: ‘Both men were brilliant, humble and completely without fear in their public utterances. In an age of mediocrity and moral pygmies, their lives shine with an intense beauty. Something of this is reflected in their correspondence, and the world is the richer for its publication.’

They agreed on some aspects of Britain and of Germany, but differed considerably on others. For example, in early 1937, Einstein wrote from Princeton to Born in Edinburgh: ‘I am extremely delighted that you have found such an excellent sphere of activity, and what’s more in the most civilised country of the day. And more than just a refuge. It seems to me that you, with your well-adjusted personality and good family background, will feel quite happy there.’ Then he contrasted his own position in the United States: ‘I have settled down splendidly here: I hibernate like a bear in a cave, and really feel more at home than ever before in all my varied existence. This bearishness has been accentuated still further by the death of my mate who was more attached to human beings than I.’

Elsa Einstein died in late December 1936 after a painful illness. ‘He has been so upset by my illness,’ she wrote of her husband not long before her death to her friend Vallentin in Paris. ‘He wanders about like a lost soul. I never thought he loved me so much. And that comforts me.’ Yet Einstein himself said nothing to others about Elsa’s death, except for his minimal remark to Born. ‘The incidental way in which Einstein describes his wife’s death, in the course of a brief description of his bear-like existence, seems rather strange. For all his kindness, sociability and love of humanity, he was nevertheless totally detached from his environment and the human beings included in it,’ Born frankly commented. As Einstein himself honestly admitted, a month before his own death, in a condolence letter to the widow of his lifelong friend Besso: ‘What I most admired in [Michele] as a human being is the fact that he managed to live for many years not only in peace but in lasting harmony with a woman – an undertaking in which I twice failed rather disgracefully.’

This difference in attitude towards human relationships between Einstein and Born – who was undoubtedly much more of a family man than Einstein – would be reflected in their attitude to post-war Germans and German responsibility for Nazism. Einstein blamed all Germans for Nazism, whereas Born was willing to draw distinctions between Germans, after the horrors of the war were over. And this was despite the fact that Born had lost thirty-four relatives and friends during the Nazi period, two-thirds of whom had committed suicide rather than face imprisonment in a concentration camp, whereas Einstein had got off much more lightly.

‘I did share your opinion, but I have now come to another conclusion,’ Born wrote to Einstein in 1950. ‘I think that in a higher sense responsibility en masse does not exist, but only that of individuals. I have met a sufficient number of decent Germans, only a few perhaps, but nevertheless genuinely decent. I assume that you may have modified your wartime views to some extent.’ Not so. Einstein remained adamant – not only about the German masses but also about German intellectuals. He had not changed his attitude to the Germans, he said, which dated from before the Nazi period. According to him, although all human beings were more or less the same from birth, ‘The Germans, however, have a far more dangerous tradition than any of the other so-called civilised nations. The present behaviour of these other nations towards the Germans merely proves to me how little human beings learn even from their most painful experiences.’

In 1953, Einstein regretted Born’s decision to migrate back ‘to the land of the mass-murderers of our kinsmen’, although he blamed it partly on the parsimony of the University of Edinburgh, which had failed to provide Born with a pension – unlike Born’s former university at Göttingen in Germany. ‘But then we know only too well that the collective conscience is a miserable little plant which is always most likely to wither just when it is needed most.’

To which Born replied: ‘I only want to tell you that the German Quakers have their headquarters in Pyrmont’, that is, the spa town in Lower Saxony where the Borns were planning to retire. ‘They are no “mass-murderers”, and many of our friends there suffered far worse things under the Nazis than you or I. One should be chary of applying epithets of this sort. The Americans have demonstrated in Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki that in sheer speed of extermination they surpass even the Nazis.’ (Later, Born even directly equated ‘Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the one hand, and Auschwitz and Belsen on the other.’) In response to Einstein’s accusation of Scottish parsimony forcing him to return, he remarked: ‘You are wrong in casting aspersions on my dear Scots; the inadequate provision for the old age of teachers and professors is quite general all over Britain, and is just as wretched in Oxford and Cambridge. If anyone is to blame it is the Swedes, who could quite well have found out about my contribution to quantum mechanics.’ Happily, the following year, 1954, just after Born’s return to Germany, the Swedish Academy in Stockholm awarded him a long-delayed Nobel prize (following its earlier awards for quantum mechanics to his collaborator Heisenberg in 1932 and Dirac/Schrödinger in 1933), partly as a consequence of the acceptance of Born’s ideas in the intervening period, promoted by Bohr and his Copenhagen school of quantum physics.

On Britain and the Jews, by contrast, Einstein and Born were in definite agreement, both before and after the Second World War. In May 1939, Born wrote to Einstein congratulating him on a speech about Palestine, which had been reported in the British press. He commented:

Without wishing to defend the wavering and unreliable British policy, I am of the opinion that the Jews could do nothing more stupid than to assume an antagonistic attitude towards the English. The British Empire is still a place of refuge and protection for the persecuted, and particularly for Jews. I also completely subscribe to what you are reported to have said concerning the need for and the possibility of coming to an understanding with the Arabs. I am glad that you have said what you did; your voice will be heard. I can only think my own thoughts in silence.

However, by 1948, the time of the expiration of the British Mandate and the foundation of the state of Israel, both Born and Einstein had changed their minds. Born now wrote to Einstein:

I was very sad when the Jews started to use terror themselves, and showed that they had learned a lesson from Hitler. Also I was so grateful towards my new ‘fatherland’, Britain, that I expected nothing evil from it. But it gradually dawned on me that our Mr Bevin [Ernest Bevin, the British foreign secretary] is playing a wicked game: first the Arabs are supplied with arms and trained; then the British army pulls out and leaves the dirty business of liquidating the Jews to the Arabs. Of course, I have no proof that it is so. Moreover, I detest nationalism of every kind, including that of the Jews. Therefore I could not get very excited about it. But gradually it has become quite obvious to me that my worst suspicions were correct. A leading article in today’s Manchester Guardian openly attacks Bevin for doing precisely what I had suspected. I am feeling very depressed, for I am completely powerless and without influence in this country. The main purpose of this letter is to tell you that you have my wholehearted support if you take any action to help. Could you not induce the American government to act before it is too late?

To which Einstein responded in wholehearted agreement: ‘Your Palestine letter has moved me very deeply. Without any doubt, you have summed up Bevin’s policy correctly. He seems to have become infected with the infamy germ by virtue of the post he occupies.’ However, he said, Born had ‘rather too optimistic an idea of the opportunities I have to influence the game in Washington. The latter can be summed up with the maxim: never let the right hand know what the left is doing. One thumps the table with the right hand, while with the left one helps England (by an embargo, for example) in its insidious attack.’

As for probability and certainty in physics, Einstein and Born remained in sharp but friendly dispute to the very end. In 1947, while continuing to labour on his unified field theory, Einstein stated his underlying belief to Born, in which he coined a phrase, ‘spooky actions at a distance’, now familiar to all physicists:

I cannot make a case for my attitude to physics which you would consider at all reasonable. I admit, of course, that there is a considerable amount of validity in the statistical approach which you were the first to recognise clearly as necessary given the framework of the existing formalism. I cannot seriously believe in it because the theory cannot be reconciled with the idea that physics should represent a reality in time and space, free from spooky actions at a distance. I am, however, not yet firmly convinced that it can really be achieved with a continuous field theory, although I have discovered a possible way of doing this which so far seems quite reasonable. The calculation difficulties are so great that I will be biting the dust long before I myself can be fully convinced of it. But I am quite convinced that someone will eventually come up with a theory whose objects, connected by laws, are not probabilities but considered facts, as used to be taken for granted until quite recently. I cannot, however, base this conviction on logical reasons, but can only produce my little finger as witness, that is, I offer no authority which would be able to command any kind of respect outside of my own hand.

After Einstein’s death, Born summed up this disagreement elegantly, in words that still resonate today:

He saw in the quantum mechanics of today a useful intermediate stage between the traditional classical physics and a still completely unknown ‘physics of the future’ based on general relativity, in which – and this he regarded as indispensable for philosophical reasons – the traditional concepts of physical reality and determinism come into their own again. Thus he regarded statistical quantum mechanics to be not wrong but ‘incomplete’.

As for his own view, he explained:

I am convinced that ideas such as absolute certainty, absolute precision, final truth, and so on are phantoms, which should be excluded from science. . . . The relaxation of the rules of thinking seems to me the greatest blessing which modern science has given us. For the belief that there is only one truth and that oneself is in possession of it, seems to me the deepest root of all that is evil in the world.

A final theme of the Born–Einstein letters concerns isolation as a source of scientific inspiration, and even genius. For Born, it had been a decidedly mixed blessing, but he recognised its value for Einstein. Solitude had been highly productive for Einstein in 1915–16, when he created his theory of general relativity in Berlin. Princeton seems to have encouraged his desire for it – and his concomitant unwillingness to return to the distractions of Europe. In 1936, Einstein told Born: ‘I personally feel very happy here, and find it indescribably enjoyable really to be able to lead a quiet life. It is, after all, no more than one deserves in one’s last terms, though it is granted to very few.’ And in 1952, he wrote: ‘One feels as if one were an Ichthyosaurus, left behind by accident. Most of our dear friends, but thank God also some of the less dear, are already gone.’ (‘What have you got against being an Ichthyosaurus?’ replied Born’s wife, Hedwig. ‘They were, after all, rather vigorous little beasts, probably able to look back on the experiences of a very long lifetime.’) To visitors in Princeton who had known him in Europe, Einstein would apparently often say: ‘You are surprised, aren’t you, at the contrast between my fame throughout the world, the fuss over me in the newspapers, and the isolation and quiet in which I live here? I wished for this isolation all my life, and now I have finally achieved it here in Princeton.’

ISOLATED FROM, OR INVOLVED WITH, FELLOW PHYSICISTS?

To what extent is this self-drawn and familiar picture of Einstein’s isolation in Princeton accurate? Not according to Buchwald and Thorne in their preface to The Born–Einstein Letters: ‘Actually, Einstein was not isolated from bright colleagues and visitors during his Princeton years. He was in lively contact with many creative physicists and mathematicians . . . and he maintained a voluminous correspondence.’

Perhaps the truth is that both pictures are accurate: Einstein was in personal contact with highly intelligent Princeton colleagues and visitors and in written contact with other physicists (including of course Born) – yet he was also aloof. ‘He always has a certain feeling of being a stranger, and even a desire to be isolated,’ remarked his biographer Frank in 1948. ‘On the other hand, however, he has a great curiosity about everything human and a great sense of humour.’

One of his collaborators, Infeld, gave a fascinating example of how this apparently contradictory combination worked, taken not from his highly theoretical work with Einstein and Hoffmann mentioned earlier, but from his joint book with Einstein on physics for a popular readership, The Evolution of Physics, published by Simon & Schuster in New York and Cambridge University Press in England. At this time, in 1937, Infeld (who had fled Poland because of anti-Semitism) had failed to win a fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study despite Einstein’s strong personal recommendation, because Princeton colleagues did not believe in the value of Einstein’s work on the unified field theory. Infeld was therefore in serious financial difficulties when he approached Einstein with his idea for a physics book capitalising on Einstein’s fame plus Infeld’s own knowledge of English. He became uncharacteristically tongue-tied with embarrassment in front of Einstein, as described in his autobiography. After an incoherent explanation of the proposed book, Infeld finally blurted out the remark: ‘The greatest men of science wrote popular books. Books still regarded as classics. Faraday’s popular lectures, Maxwell’s Matter and Motion, the popular writings of Helmholtz and Boltzmann still make exciting reading.’ Einstein looked at him silently, stroked his moustache with his finger and then said quietly: ‘This is not at all a stupid idea. Not stupid at all.’ He got up, stretched out his hand and said: ‘We shall do it.’

Einstein took the challenge to heart and was increasingly enthusiastic as the work progressed, saying repeatedly: ‘This was a splendid idea of yours.’ He believed that the fundamental ideas of physics could be expressed in words, commenting: ‘No scientist thinks in formulae.’ They discussed and revised the manuscript over and over again until it was in its final form, in a remarkable collaboration which captured the complexity of the subject while also making it intelligible to the ordinary reader (unlike Einstein’s own short book on relativity, as Einstein well knew). Not once did Einstein try to pull rank over Infeld. ‘Then suddenly Einstein lost all interest. His interest lasted exactly as long as our work lasted. It ended the moment our work was finished.’ When the advance copies arrived from Simon & Schuster, Infeld took them to Einstein. He was completely uninterested and did not even open the book. ‘Once a work is finished his interest in it ceases. The same applies to the reprints of his scientific papers. Later he had to autograph so many copies of our book that automatically, when he saw a blue jacket, he groped for his fountain pen.’ But for Infeld – known forever after as the ‘man who worked with Einstein’ – publication of the book was an adventure that changed both his intellectual outlook and his academic career.

DRAWN INTO POLITICS BY NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND THE COLD WAR

With the evolution of physics into nuclear physics in the 1930s, the dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan in 1945 and the end of the Second World War, Einstein was drawn into American and international politics – whether or not he would have preferred to remain aloof. His only reaction on hearing the radio announcement of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima relayed to him by his secretary Dukas was ‘Oj weh’ (Yiddish for ‘Woe is me’). But soon he began a public campaign to control atomic and nuclear weapons by calling for a new political ethics. This culminated in his appeal in 1950 against the development of the hydrogen bomb in a nationwide television programme hosted by Eleanor Roosevelt: a broadcast regarded as so subversive by the Federal Bureau of Investigation director, J. Edgar Hoover, that the FBI and the Immigration and Naturalization Service launched a top-secret investigation aimed at revoking Einstein’s American citizenship, so that he could be deported from America. (Even US President Dwight Eisenhower was kept in the dark, judging from his eulogy of Einstein after his death: ‘Americans are proud that he sought and found here a climate of freedom in his search for knowledge and truth.’ He further commented: ‘No other man contributed so much to the vast expansion of twentieth-century knowledge.’)

Einstein hoped that the fresh horrors of the Second World War and the obvious potential horrors of a nuclear third world war might together be enough to force reform in international affairs. ‘We must realise we cannot simultaneously plan for war and for peace,’ he told the New York Times. As he put it on the occasion of the fifth Nobel anniversary dinner in New York in December 1945, ‘The war is won, but the peace is not.’ He began his speech: ‘Physicists find themselves in a position not unlike that of Alfred Nobel. He invented the most powerful explosive ever known up to his time, a means of destruction par excellence. In order to atone for this, in order to relieve his human conscience, he instituted his awards for the promotion of peace and for achievements of peace.’ And he concluded: ‘The situation calls for a courageous effort, for a radical change in our whole attitude, in the entire political concept.’ He evoked the name of Nobel: ‘May the spirit that prompted Alfred Nobel to create his great institution, the spirit of trust and confidence, of generosity and brotherhood among men, prevail in the minds of those upon whose decisions our destiny rests. Otherwise, human civilisation will be doomed.’

Einstein’s main practical recommendation for managing nuclear weapons (which he sensibly anticipated the Soviet Union would soon develop) was that they could be controlled only by what he called a ‘world government’. This would be an essentially military organisation, to which the world’s leading nations would contribute armed forces, which would then be ‘commingled and distributed as were the regiments of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire’, and which would have the power to enforce international law according to the direction of its representative executive. ‘Do I fear the tyranny of a world government? Of course I do. But I fear still more the coming of another war or wars.’ The United States, he said, should immediately announce its readiness to commit the secret of the atomic bomb to this world government. And the Soviet Union should be sincerely invited to join it. In September 1947, Einstein proposed his idea in an open letter to the General Assembly of the United Nations. If the UN were to have a chance of becoming such a world government, he said, then ‘the authority of the General Assembly must be increased so that the Security Council as well as all other bodies of the UN will be subordinated to it.’ (He even grimly suggested to an American friend that ‘it might not be altogether illogical to place a statue of the contemptible Hitler in the vestibule of the future palace of world government since he, ironically, has greatly helped to convince many people of the necessity of a supranational organisation’.)

Perhaps needless to say, as the Cold War hotted up in 1947, no leading power was remotely interested in Einstein’s world government. It was assailed from all sides. Four top scientists of the Russian Academy replied respectfully but in unequivocal opposition, virtually accusing Einstein of advocating American imperialism. Einstein was not surprised but pleaded in response that:

If we hold fast to the concept and practice of unlimited sovereignty of nations it only means that each country reserves the right for itself of pursuing its objectives through warlike means. . . . I advocate world government because I am convinced that there is no other possible way of eliminating the most terrible danger in which man has ever found himself.

‘World government’ enjoyed a brief vogue among a spectrum of American intellectuals – on the right as well as on the left – and then faded from view. So too did the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, a brainchild of Szilard, which Einstein agreed to chair in May 1946. Both fell victim to the Cold War.

More effective was Einstein’s opposition to Senator Joseph McCarthy and his 1950s Red Scare in the United States. Einstein helped to turn the tide against the climate of fear and precipitate the decline of McCarthyism. In this period he made a number of public statements and supported several individuals threatened with dismissal from their jobs for having Communist sympathies. But the one that really stirred public controversy was Einstein’s letter to a New York teacher of English, William Frauenglass, in May 1953. Frauenglass had refused to testify before a congressional committee about his political affiliations and now faced dismissal from his school. He asked for advice from Einstein, who wrote (no doubt thinking of his experience of German intellectuals in the First World War and under Nazism):

The reactionary politicians have managed to instil suspicion of all intellectual efforts into the public by dangling before their eyes a danger from without. . . . What ought the minority of intellectuals to do against this evil? Frankly, I can only see the revolutionary way of non-cooperation in the sense of Gandhi’s. Every intellectual who is called before one of the committees ought to refuse to testify, i.e., he must be prepared for jail and economic ruin, in short, for the sacrifice of his personal welfare in the interest of the cultural welfare of his country. . . . If enough people are ready to take this grave step they will be successful. If not, then the intellectuals of this country deserve nothing better than the slavery which is intended for them.

Mahatma Gandhi was ‘the greatest political genius of our time’, wrote Einstein in 1952. ‘His work on behalf of India’s liberation is living testimony to the fact that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction, is more powerful than material forces that seem insurmountable.’

When the advice to Frauenglass was published in the New York Times with Einstein’s permission, he feared that, at the age of seventy-four and in poor health, he might have to go to jail. Immediately, McCarthy told the paper that ‘anyone who gives advice like Einstein’s to Frauenglass is himself an enemy of America. . . . That’s the same advice given by every Communist lawyer that has ever appeared before our committee.’ (A week later, he modified ‘enemy of America’ to ‘a disloyal American’.) The New York Times, in an editorial, agreed with McCarthy’s criticism of Einstein’s advice.

At the same time, Einstein received two expressions of support from England. The first was a private cable from Locker-Lampson, sent on the very day of McCarthy’s first published statement against Einstein. Long out of contact with Einstein, and now a retired recluse living in London, but still the impulsive romantic he was in 1933, Locker-Lampson recalled their alliance against Nazism: ‘Commander Locker-Lampson offers same humble hut as sanctuary in England.’ The second was a punchy public letter from Bertrand Russell. It was published after some delay caused by internal debate within the New York Times. Russell wrote:

In your issue of June 13 you have a leading article disagreeing with Einstein’s view that teachers questioned by Senator McCarthy’s emissaries should refuse to testify. You seem to maintain that one should always obey the law, however bad. I cannot think you have realised the implications of this position.

Do you condemn the Christian martyrs who refused to sacrifice to the emperor? Do you condemn John Brown? Nay, more, I am compelled to suppose that you condemn George Washington, and hold that your country ought to return to allegiance to Her Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. As a loyal Briton I of course applaud your view, but I fear it may not win much support in your country.

Einstein responded privately to Russell with deep appreciation on 28 June:

All the intellectuals in this country, down to the youngest student, have become completely intimidated. Virtually no one of ‘prominence’ besides yourself has actually challenged these absurdities in which the politicians have become engaged. . . . The cruder the tales they spread, the more assured they feel of their re-election by the misguided population.

Hence the fact, he added, that President Eisenhower had not dared to commute the death sentences of the Soviet spies Ethel and Julius Rosenberg – American citizens who had been electrocuted on 19 June – even though Eisenhower ‘well knew how much their execution would injure the name of the United States internationally.

You should be given much credit for having used your unique literary talent in the service of public enlightenment and education. I am convinced that your literary work will exercise a great and lasting influence particularly since you have resisted the temptation to gain some short-lived effects through paradoxes and exaggerations.

THE RUSSELL–EINSTEIN MANIFESTO

No doubt this exchange prepared the ground for what would be the last public act of Einstein’s life: the Russell–Einstein Manifesto of 1955. It started with a letter from Russell to Einstein in February 1955, which began:

In common with every other thinking person, I am profoundly disquieted by the armaments race in nuclear weapons. You have on various occasions given expression to feelings and opinions with which I am in close agreement. I think that eminent men of science ought to do something dramatic to bring home to the public and governments the disasters that may occur. Do you think it would be possible to get, say, six men of the very highest scientific repute, headed by yourself, to make a very solemn statement about the imperative necessity of avoiding war? These men should be so diverse in their politics that any statement signed by all of them would be obviously free from pro-Communist or anti-Communist bias.

Einstein was immediately responsive. In fact he suggested upping the number of signatories to ‘twelve persons whose scientific attainments (scientific in the widest sense) have gained them international stature and whose declarations will not lose any effectiveness on account of their political affiliations’. In the United States, the choice would be particularly tricky, he said, because ‘this country has been ravaged by a political plague that has by no means spared scientists’. As for obtaining Russian signatures, his colleague L. Infeld, professor at the University of Warsaw, might possibly be of assistance.

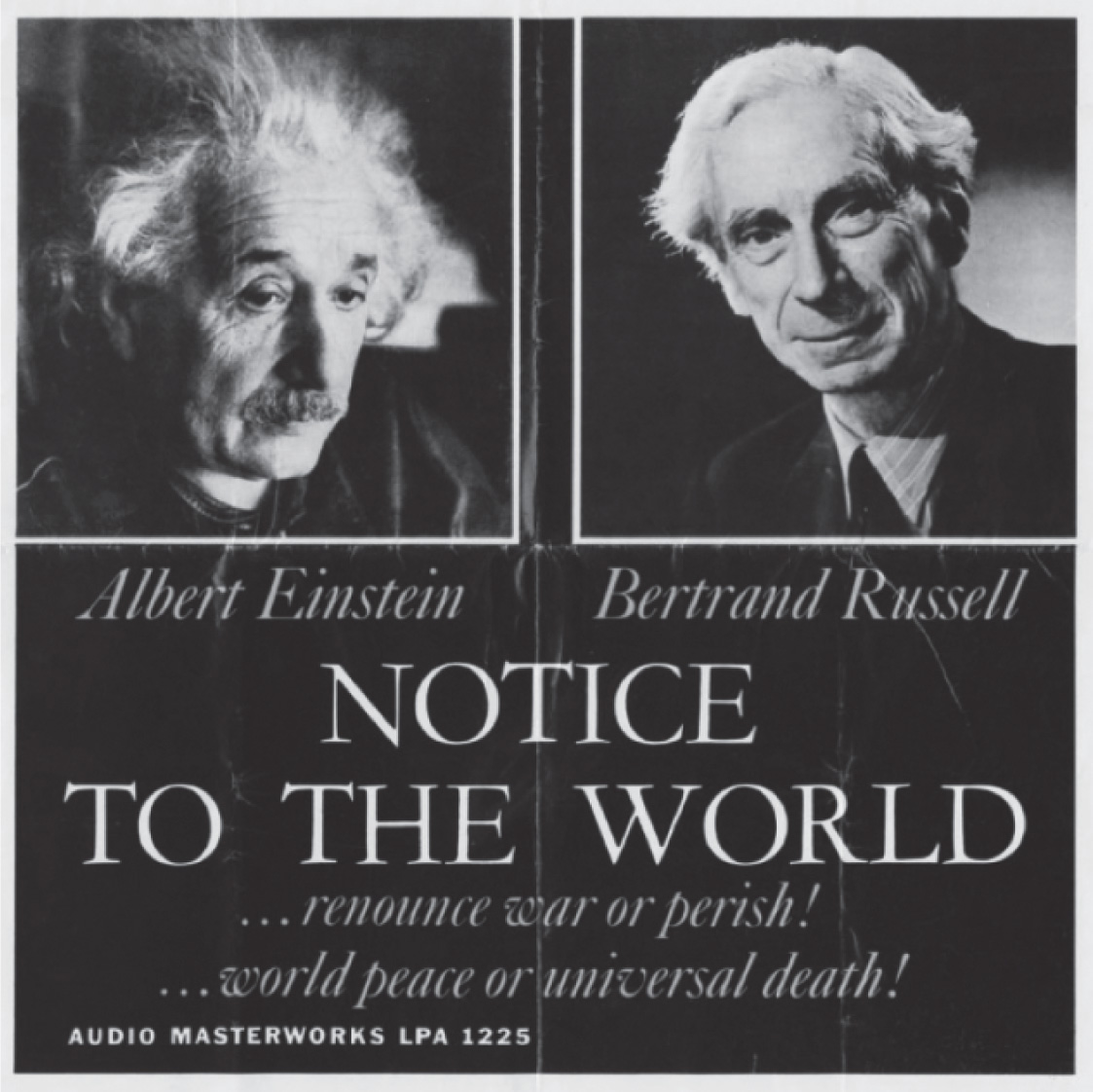

Einstein’s signature, on 11 April, was the last one he ever gave. It reached Russell only after Einstein’s death. The statement was made public at a meeting called by him in London in July 1955. The other nine signatories, apart from Einstein and Russell, were all scientists, the majority of them physicists: Max Born (from Germany), Percy Bridgman (United States), Leopold Infeld (Poland), Frédéric Joliot-Curie (France), Hermann Muller (United States), Linus Pauling (United States), Cecil Powell (Britain), Joseph Rotblat (Britain) and Hideki Yukawa (Japan). All eleven of them, except for Infeld, received the Nobel prize (twice over in the case of Pauling, for both chemistry and peace). Significantly, there was no signatory from the Soviet Union.

The Russell–Einstein Manifesto against nuclear weapons, 1955: cover of a sound recording made by Bertrand Russell after Einstein’s death in April. It was Einstein’s last, and most enduring, political statement.

The final paragraph of the manifesto warned:

There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal, as human beings, to human beings: Remember your humanity and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

As Rotblat, the youngest signatory, regretted in an article about ‘Einstein’s quest for global peace’ written shortly before his own death in 2005, this warning ‘is as valid today as it was then’. Rotblat had spent the half-century since signing the manifesto in building up the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, meeting in the village of Pugwash in Canada with the aim of bringing together intellectuals and public figures to promote dialogue towards reducing the dangers of armed conflict. In 1995, he and Pugwash were jointly awarded the Nobel peace prize.

Einstein himself was lucky with his death. He had once told Infeld: ‘if I knew that I should have to die in three hours it would impress me very little. I should think how best to use the last three hours, then quietly order my papers and lie peacefully down.’ Soon after writing to Russell, he was taken to a Princeton hospital, still in possession of all his faculties but knowing that his death was imminent. He died early in the morning of 18 April, leaving pages of calculations about his unified field theory beside his bed.