A BLUE cloud uneasy with electricity had swallowed the peaks of the Taygetus. The valleys rumbled with thunder and even a few phenomenal drops of rain pattered on the hot planks of the deck. But, as strangely as the cloud had spun itself out of nothing, it dwindled and shrank and finally, reduced to a static and solitary puff, vanished, exposing the western flanks of the Mani once more in all their devastating blankness. The Taygetus rolls in peak after peak to its southernmost tip, a huge pale grey bulk with nothing to interrupt its monotony. Nothing but a tangle of swirling incomprehensible creases of strata strangely upheaved. Every hour or so a dwarf township, queerly named, sprouted from the hot limestone at the water’s edge: Stoupa, Selinitza, Trakhila, Khotasia, Arfingia. Little towers, with heavily barred windows and circular turrets at the corners, dominated a narrow shelf of whitewashed quay. Village elders (among which there is always the black cylinder of a priest’s hat) sat over their coffee on the ramparts clicking their amber beads as they watched the pother of loading and unloading. Sacks of flour were piled among the capstans and lashed to the waiting mule teams which set off amid the shouts and whacks of their muleteers up labyrinthine torrent-beds for barren invisible hamlets in the hinterland.

Trakhila was backed by a blessed dark screen of cypresses. (It is strange how certain trees can civilize the wildest landscape in the same way that a single spruce or Christmas tree can barbarize the most amenable in a trice.) Then the blinding emptiness continued for mile on mile over our port bow. Now and then, shadowless in the blaze, built of the surrounding rock and only with difficulty discernible from the mountain, a lonely house would appear. Once, on a high ledge, an ashy village was outlined by a thin kindly smear of green and later a castellated house stood by the water in a sudden jungle of unlikely green which turned out, as I strained my eyes, to be all cactus and prickly pear—Frankish figs as the Greeks call them—flourishing there with the same deceptive air of freshness with which a cascade of mesembrianthemum will run wild over a hill of pumice.

This was all reflected in a sea which lay as flat as a looking-glass except for the ruffle of our wake. Yet among the wheat sacks the dolorous face of many a black-coiffed crone spelt sea-sickness. This is a peculiar convention: for land-lubbers, the sea equals seasickness, just as passing a church evokes a sign of the cross, a funeral, tears and torn hair, and the mention of war, a deep sigh. It is none the less genuine for that, and to exorcize this ritual nausea, the smell of a cut lemon is thought to be sovereign. Accordingly, they all held these golden pomanders to their nostrils.... At Trakhila a man got in who was so dark that, if he had been in the West Indies or Egypt one would have assumed that he had a strong dash of Negro blood in his veins. The Captain, at a suitable moment, whispered that the stranger came from the Deep Mani; many of them, he said, were like that, as the result of the old slave market of Vitylo, where the Berber and Algerian pirates, as well as the Venetians and the Maniots themselves, used to put up their captives for sale. Or rather, he cautiously appended, that is what they say.[1]

Soon we were rounding a cape and sailing at a slant across a broad inlet that penetrated a few miles into the mountains. At the further end lay Oetylus (Vitylo or Itylo) and a jag of rock smothered by the sprawling ruin of a great castle. It was the Fortress of Kelepha, built here by the Turks as a temporary foothold on the edge of the Mani they had never managed to subdue. But we were heading for the southern shore of the gulf, the frontiers—at last!—of the Deep Mani itself. A derelict, shadowless little port and a group of empty houses bereft of life appeared at the bottom of steep olive-covered rocks. The engine fell silent, and, as we drew alongside, the roar of millions of cicadas burst on the ear. It came from the shore in rhythmic, grating, metallic waves like the engines of an immense factory in a frenzy—the electric rattle of innumerable high-powered dynamos whirling in aimless unison. There was not a breath of wind and on the quay when we left the caique’s cool awning the sun came stampeding down to the attack. We plunged for shelter into a slovenly kapheneion awhirl with flies. Lulled by their buzz and by the ear-splitting clatter outside we lay on the sticky benches for an hour or two, till the sun should decline a little and declare a truce.

* * *

The road to the upper world was a stony way ribbed with cut blades of rock to afford purchase for the feet of mules bearing cargoes up to Areopolis from the hot little port of Limeni. Each olive tree, motionless in the still air, was turned by the insects into a giant rattle, a whirling canister of iron filings. But as the stony angles of road levered us higher the clamour fell behind and the road, swept by a cool breeze, flattened across two miles of a bare plateau, dropping abruptly to the sea on the west and soaring eastwards once more in a continuation of the Taygetus; and there ahead of us, half castellated and with its roofs topped by a tower or two and the cupola and belfry of a little cathedral—lay the capital of the Deep Mani. The narrow streets of Areopolis were all round us.

It had the airy feeling of all plateau-towns and in the direction of the Messenian Gulf the lanes ended in the sky like springboards. Inland the impending amphitheatre was fainting from its afternoon starkness into a series of softly-shadowed mauve cones. In these solemn surroundings the little capital held an aura of solitude and remoteness. But the sloping cobbled lanes were full of gregarious life as if the Maniots had herded there in flight from the cactus-haunted emptiness outside. Except for the Cypriots; they were the darkest Greeks I have ever seen. But whereas the Cypriots have soft and rather shapeless faces, the Maniots are lean and hewn-looking with blue jowls and rebellious moustaches. Their jet and densely-planted hair grows low on the forehead; it narrows their temples; and fierce bars of brow are twisted in scowling flourishes over black and wary eyes as if the brains behind them were hissing with vindictive thoughts. It was this fell glance that distinguished them, it occurred to me, from the Cretan mountaineers they might otherwise resemble. The eyes of the latter are open and filled with humour and alacrity. But, blackavized as they looked under their great hats, this cast of sternness and caution must be the atavistic physical trace of centuries of wild life, for their manners were the reverse. As we descended the cobbled streets, a murmur of greeting rose from the café tables in a quiet chorus uttered with a friendliness and grace that made one feel welcome indeed. (This is not usual in towns; even in villages it is the convention for strangers to greet first.)

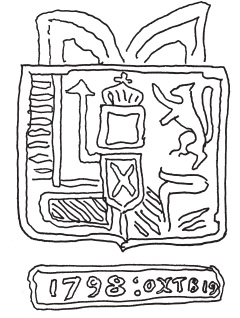

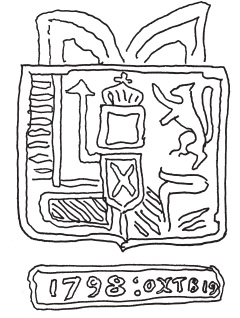

The names over the shops had all changed once more from the -eas ending of the Outer Mani to the -akos of the Deep: Kostakos, Khamodrakos, Bakakos, Xanthakos. At the bottom of the main street, a primitive cathedral, smaller than a small parish church in England, stood in a cluster of mulberry trees. It was entirely whitewashed and topped by a tiled Byzantine cupola supported on a drum of pilasters and arches and flanked by a snow-white tapering belfry. A course of moulding painted bright yellow girdled the ribbed apse. Studded with alternate pink rosettes and bright green leaves, it might have been the decoration of a Mayan Baroque church in the uplands of Gua-temala. Higher on the walls mauve pilasters supported a shallow colonnade enclosing panels of apricot, and clumsy six-winged seraphim spread their feathers in bossed and lumpy relief. Two childish sun-discs were surrounded by spiked petals adorned with currant-like eyes and wide grins, and the signs of the Zodiac sported across the whitewash in an uncouth and engaging menagerie. The decoration over the main door was a real puzzle: a large panel in the same lumpy relief was picked out in yellow and black and green. Tudor roses and leaves and rosettes and nursery-rhyme suns formed a background for two angels, one in fluted robes, the other in armour and buskins; and between them, supported by two small and primitive lions rampant, a double-headed eagle with wings displayed bore on its breast a complicated shield whose strange charges had so often been painted over that it was hard, even standing on a café chair, to make them out. The eagle’s two heads were backed by haloes, and something like the vestigial memory of a closed crown rested on the top of the shield while above the bird’s heads an imperial crown, like that of Austria-Hungary or the Russian Empire, spread its two mitre-like ribbons. A scroll underneath bore the date of 1798.

The double-headed eagle, the emblem of Byzantium and, in a sense, of the Orthodox Church, is a frequently recurring symbol in ecclesiastical decoration; the formula of its representation on the walls and floors of churches has scarcely changed since the imperial eagle of Rome grew a second head when Constantine founded the Empire of the East in 330. But the heraldic elaboration of the plaster bird over the door bore no resemblance to it. For all its uncouthness, the design—the haloes, the arrangement of wings and claws and tail—echoed the sophistication and formalism of latter-day western heraldry. I wondered if it could have been copied, quite arbitrarily, from the arms on a Maria Theresa thaler as pure decoration; but except for the fesses (or stripes) in the dexter chief which faintly resemble part of the Hungarian arms there is no similarity. Could they be inspired by the arms of Russia? It was unlikely, because of the date, which was twenty years after Orloff’s abortive campaign in the Peloponnese, which effectively discredited Russia as the protectress of Orthodoxy. The only important event in local history for 1798 is the accession of Panayioti Koumoundouros as fifth Bey of the Mani. But, great local potentates as were the Beys, I have never heard that they adopted the use of arms. These emblems, with that date attached, seemed (and still seem) as problematical as an Easter Island statue in the Hebrides. I attach a faithful copy of this half-obliterated shield in case anyone can identify it and perhaps unearth a lost chapter of Maniot history.

In the blue-green sky beyond the mulberry leaves a bright star was burning so close to the waxing crescent of the moon that it seemed to have invaded the dim perimeter, forming a celestial Turkish flag. Most unsuitably, when one remembers the Mani’s history.

* * *

Very little is known about this remote province in the rest of the country but the name of the Mani at once suggests four ideas to any Greek: the custom of the blood feud; dirges; Petrobey Mavromichalis, the leader of the Maniots in the Greek War of Independence; and the fact that the Mani, with the Sphakian mountains of Crete and, for a while, the crags of Souli in Epirus, was the only place in Greece which wrested its freedom from the Turks and maintained a precarious independence. This, too, was about the sum of my knowledge, amplified by the haze of rumours, which (as so few non-Maniot Greeks ever go to the Mani) riots unchecked beyond the Taygetus. This deviation from the main flow of Greek history has produced many divergent symptoms and, before going further into its remoter depths, it is worth looking at the things in the Mani’s past which have contributed to this idiosyncrasy.

Its geographical seclusion, locked away beyond the mountains on the confines of Sparta, and the steepness and aridity of its mountains are the key to the whole thing. Its history was one with that of Sparta until the monarchy ended at the turn of the third and second centuries B.C., when the cruelty of the tyrant Nabis decided many of the Spartans to flee beyond the Taygetus and found, with the Laconian inhabitants already established in the peninsula, a shadowy Republic of the Laco-nians. This was the first of the many flights for asylum which helped to form the present Mani. Their liberties went unmolested after the Roman conquest, which happened a few years after. Later on, Augustus, out of gratitude for Laconian help in the defeat of Mark Antony at Actium, confirmed these rights, and their history was without event until the Republic of Free Laconians was dissolved by Diocletian in his reform of the provincial administration in A.D. 297. The uneventful, orderly life continued under Byzantium, except for a new contribution of Spartans in flight from the Visigoths of Alaric in 396. The invasions of Slavs and Bulgars in the centuries which followed sent fresh waves of refugees; worse still, a savage Slav tribe, the Meligs, established themselves in the peaks of the Taygetus.

They were a terrible lot: strangers, talking a foreign tongue, who lived by brigandage. It is impossible to say how many they were, or how much they were absorbed into the Laconian stock of the Maniots. According to the only available sources, very little. Constantine Porphyrogenetus (who reigned at Constantinople at the beginning of the tenth century) mentions them in the book—a kind of geographical and diplomatic history and guide to the Empire—which he wrote for the instruction of his son Romanus. After describing them, he expressly states that the Maniots themselves are unpolluted descendants of the old pagan Greeks. St. Nikon the Penitent, who converted the area from paganism a few decades later, found these Meligs an appalling handful. Peak-wandering robbers who lived off loot, they were “led by the devil, entering houses by night like wolves...miserable and evil fiends, bloodthirsty murderers, whose feet were forever leading them into evil....” (The saint baffled them by enveloping them in snowy clouds, and once, when some had robbed a monastery, he discomfited them with two huge mastiffs. But he managed to convert them in the end.) This turbulent minority, often mentioned in the Chronicle of the Morea, with time quite lost their language and their tribal conscience and by the twelfth century they were, like the other Slavs, swallowed up without trace in the Greek Orthodox Christian world of the Peloponnese. Sealed off from outside influences by their mountains, the semi-troglodytic Maniots themselves were the last of the Greeks to be converted. They only abandoned the old religion of Greece towards the end of the ninth century. It is surprising to remember that this peninsula of rock, so near the heart of the Levant from which Chris-tianity springs, should have been baptised three whole centuries after the arrival of St. Augustine in far-away Kent.

The Frankish conquest of the Morea in the thirteenth century, when the Mani became part of the feudal fief of the Ville-hardouins, brought another swarm of refugees from Byzantine Sparta across the mountains; the falls of Constantinople and Mistra and Trebizond, yet more. Meanwhile, the pacific nature of the old Maniots had been changing—a process which began, perhaps, after the Byzantine victory over the Franks at Pelagonia[2] in 1261, when Emmanuel Palaeologus reclaimed the south-eastern Peloponnese for the Empire. The Frankish conquest had been a walkover; but, when the final disaster of Turkish invasion came, the Mani put up a stiff resistance: contact with the warlike Franks, their military training, and the late Byzantine triumphs in the empire’s twilight had turned these descendants of the Spartans, quiescent almost since Thermopylae, into implacable warriors.

Their exploits against the Turks became fabulous and their feats of arms under their Epirote leader, Korkodeilos Kladas—the first of many guerrilla heroes—are some of the most brilliant in Peloponnesian history. In fact, so formidable were the swords and guns and the rocks of the Mani that, apart from punitive inroads in strength and the construction of one or two massive fortresses in which garrisons were cooped for uncertain and dangerous sojourns, the Mani remained miraculously free. More contingents arrived in flight from other parts of the occupied Greek world; a few from Asia Minor, and, after the Turkish capture of Crete from the Venetians at the end of the long siege of Candia[3] in 1669, a heavy shower of Cretans, who founded villages with Cretan names and scattered the already complex Maniot dialect with Cretan words and constructions; so that, to the Maniot -eas and -akos surnames were now added many that ended with the Cretan -akis.[4] This steady influx of strangers and the struggle, among the rocks and cactuses, for lebensraum, launched the Maniots, old and new, on innumerable vendettas between rival villages and families and clans. A kind of tribal system grew up not unlike that of the Scottish Highlands before the ’45.

Some of these vendettas grew into miniature local wars and kept the Mani smoking with turbulence and bloodshed for centuries. For centuries, in fact, the only thing that could reconcile them was a Turkish inroad, when, suddenly, for brief idyllic periods of internal harmony, their long guns would all point the same way. Parties would leave to fight as mercenaries in the armies of the Doge. The poverty of the peninsula turned the Maniots into pirates, and their little ships were the terror of the Turkish and Venetian galleys in southern Peloponnesian waters. Their expeditions were undertaken less in search of riches than for the sober domestic need to buy wood,—fuel for lime burning for the building of tall towers in their treeless villages—and guns, with which to shoot at their neighbours through the loopholes when these were built. Many of their piratical exploits, like those of the klephts and armatoles in the mountains of the mainland, had a patriotic reason. The best known case is the destruction of part of the Ottoman fleet in Canea roads with Maniot fire-ships.

The hamlets of the Mani were scattered across the mountains like scores of hornets’ nests permanently at odds with each other, a discord which, as we have seen, only the Turks could resolve; so the Turks wisely left them alone under the rule of a Maniot holding the title of Bey of the Mani and the powers of a reigning prince; something after the style of the hospodars of Wallachia and Moldavia, with a nominal yearly tribute. But it was seldom paid. Once, I was told, a farthing was derisively tossed to the Sultan’s representative from the tip of a scimitar.

The first of these rulers, Liberakis Yerakaris, reigned in the middle of the seventeenth century. By the age of twenty he had served several years as an oarsman in the Venetian galleys and made himself the foremost pirate of the Mani. Captured by the Turks and condemned to death, he was reprieved by the Grand Vizier—the great Albanian Achmet Küprülü—on condition that he accepted the hegemony of the Mani. He undertook the office in order to avenge himself on the strong Maniot family of the Stephanopoli with which he was in feud. He at once besieged them in the fort of Vitylo and captured thirty-five of them whom he executed on the spot. For the next twenty years he used his power and his influence with the Sublime Porte to campaign all over the Peloponnese and central Greece at the head of formidable armies, siding now with the Turks, now with the Venetians, marrying the beautiful princess Anastasia, niece of a Voivode of Wallachia,[5] ending his life, after adventures comparable to anything in the annals of the Italian condottiere, as Turkish Prince of the Mani and Venetian Lord of the Roumeli and Knight of St. Mark.

The Turks did not repeat the experiment for a hundred years. After the Orloff revolt petered out in 1774, the Turks revived the rank of Bey of the Mani, thinking it was wiser to have one man responsible for the tranquillity of the district. So during the forty-five years from 1776 to 1821, when the War of In-dependence broke out, the Mani was ruled by eight successive Beys, all except one of whom played the dangerous game of maintaining the interests of the Mani and of eventual Greek freedom while trying to remain on the right side of the Turks.[6] Two were tricked on board Turkish men-of-war and executed in Constantinople: one for attempting to extend his beydom beyond the Eurotas, the other as the result of intrigues at the Sublime Porte. The third, the wealthy Zanetbey, a great tower-builder, was deposed for his collusion with the Klephts and the discovery of a secret and treasonable correspondence with Na-poleon, to whom he looked as a possible deliverer of the Mani. (He had prudently sent one of his sons to serve in the French army, another in the Russian.) He contrived to save his life by flight, continued his negotiations with the French and even persuaded them to send him boatloads of arms and ammunition which he distributed among the klephts and the kapetans. His successor was deposed for failing to put a stop to these dangerous goings-on. The fifth had a quiet reign. He organized the internal economy of the Mani, built roads, and became a member of the Philiki Hetairia, the secret revolutionary society which had begun to penetrate the whole Greek world. He was deposed for suspected collusion with his turbulent and outlawed uncle, Zanetbey, and was succeeded by his detractor, Zervobey, the only quisling. He was attacked by the family of Zanet and he only saved his life by seeking refuge in the palace at Tripoli with his friend the tyrannous and depraved Veli, Pasha of the Morea and son of no less a person than the terrible Vizier of Yannina, Ali the Lion. The career of his successor is overshadowed by that of the eighth and last of the Beys, the greatest of them all and one of the leading figures of Greek nineteenth-century history, Petrobey Mavromichalis.

After the Frankish conquest of Greece the Mani was a stormy feudal oligarchy of powerful families. Of these by far the strongest, the richest and the most numerous was the Mavromichalis clan. Various origins have been ascribed to them. There is a tradition that they were originally a Thracian family called Gregorianos which arrived here in flight when the Turks first crossed the Hellespont in 1340. It is certain that they were established in the west of the Deep Mani by the sixteenth century. In chronicles of the following centuries, the name abounds. There is a deep-rooted legend that their great physical beauty springs from the marriage of a George Mavromichalis to a mermaid; in the same way that anyone of the name of Connolly, in Celtic folklore, descends from a seal.[7] Their courage and enterprise were equal to their beauty, and Skyloyanni Mavromichalis—John the Dog—was one of the great paladins against the Turks in the eighteenth century. His son Petro was head of this vast family at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the Mavromichalis were at the acme of their prosperity and power, a position chiefly due to the strategic and mercantile importance of their hereditary stronghold in the natural fortress of Tsimova and its attendant port of Limeni. This commands the only pass leading through the Taygetus to Gytheion and the rest of Laconia; it is also the entrance to the Deep Mani. Long before he was created Bey, his territorial influence and authority far exceeded that of his pre-decessors and when the beydom devolved upon him in 1808 it was the ratification of power which was already absolute. His fine looks and dignity and gracious manners were the outward signs of an upright and honourable nature, high intelligence, diplomatic skill, generosity, patriotism, unshakable courage and strength of will: qualities suitably leavened by ambition and family pride and occasionally marred by cruelty. He too negotiated with Napoleon (to no great purpose, however, as the latter was too occupied elsewhere) and reconciled the warring clans. He imposed a truce to the feuds and conciliated the Troupakis and Grigorakis clans. These, egged on by the Turks in the hope that internal strife might soften up the Mani for invasion or at least neutralize it in the coming struggle for the liberation of Greece, were rival aspirants to the rank of Bey.

It was from the Mani that the first blow was struck. Petrobey and three thousand Maniots with Kolokotronis and a number of the great Morean klephts advanced on the Turkish garrison of Kalamata. After its surrender he issued a declaration of the Greek aspirations to the courts of Europe signed “Petrobey Mavromichalis, Prince and Commander in Chief.” The banners of freedom were going up all over Greece, and the whole peninsula burst into those flames which, after four centuries of slavery, demolished the Turkish power in the country for ever and gave rebirth to the shining phoenix of modern Greece. Petrobey, at the head of his Maniots, fought battle after battle in these ferocious years; he takes his place as one of the giants in the struggle. He soars far beyond the rocky limitations of these pages into those of modern European history. No less than forty-nine of his family were killed during this contest and his capital of Tsimova was renamed Areopolis in his honour: the town of the war-god Ares. In the tangle of conflicting ideologies which followed the liberation Mavromichalis fell out with the new leader of the State, Capodistria. When he was imprisoned in the new capital at Nauplia, the Mani rose in revolt and Petrobey escaped and fled; but he was recaptured and re-imprisoned and two of his turbulent nephews, enraged at this insult, waylaid Capodistria and assassinated him. Mavromi-chalis achieved high honours during the reign of King Otto and died, surrounded with glory, in 1848. His descendants have played a prominent part in governments and war cabinets ever since, though none of them—how could they in the Athenian world of party-politics?—have equalled the stature of their great ancestor.

The name still rings unchallenged through the Mani and at that very moment the narrow streets of Areopolis were plastered with election posters displaying photographs of Petro Mavromichalis, a great-great grandson and the present head of the family, a political figure of some prominence in the Royalist interest. His urbane, well nourished and patrician face, a monocle glinting in one eye socket, issuing from a stiff collar with a carefully knotted tie and well tailored shoulders, looked out over the broad Maniot hat-brims with a nice combination of ministerial poise and the affability of the bridge-table. It was hard to associate these polished lineaments with the shaggy yataghan-wielding chieftains of the Deep Mani; with Black Michael and John the Dog. Still less with that beautiful mermaid floundering wide-eyed in a rock pool in the gulf of Kyparissia a few centuries ago.

[1] I have been able to find no verification of this Mani slave-market though the Maniots used to be famous corsairs and were not infrequently mixed up in the trading of slaves. Once in a blue moon one comes across a villager in the Morea whose appearance is ascribed to an isolated rape, a hundred and thirty odd years ago, by the Sudanese cavalry of Ibrahim Pasha.

[2] Monastir (Bitolj), now just across the Serbian border.

[3] Herakleion.

[4] This ending is not always Cretan. The formation existed in the Mani.

[5] A member of the Duca family.

[6] They were Zanetos Koutipharis (3 years), Michaelbey Troupakis (3 years), Zanetbey Kapetanakis Grigorakis (14 years), Panayoti Koumoundouros (5 years), Antonbey Grigorakis (7 years), Zervobey (2 years), Thodorobey Zanetakis (5 years) and the Petrobey Mavromichalis (6 years).

[7] Nereids—the word used in the account of this legend—in modern Greek superstition are beautiful pale wraiths who haunt inland streams and springs. But this one is expressly stated to have been a salt-water dweller. The nereid, as opposed to the salt-water “gorgon,” is shaped like a human. The latter, the Gorgona that haunts the stormier parts of the Mediterranean, ends in two scaly and coiling tails. A Maniot grocer told me that the Mavromichalis nereid was possibly a deaf and dumb Venetian princess of the House of Morosini found sitting on a rock by the seashore.