Aphrodite, Cythera, was painted smartly across the poop of the fast and racy looking caique we boarded next morning. Indeed, everything was as bright as a pin. There was silver paint on the cleats and, along the bows, touches of grass green, ox-blood and gilding in the swirl of carved wooden foliage from which the bowsprit sprang. The mast was painted in the blue and white Greek colours in a bold barber’s pole spiral for a third of its height. A tin framed picture of St. Catherine was nailed to it and on a folded sailor’s jacket a sleek and well-fed tortoiseshell cat stretched sleepily at the pother of embarkation. The entire glittering craft, presided over by a jolly whiskered Cerigiot captain who abetted our embarkation with cheerful cries of “aidé!” and a hauling hand stretched overboard and avuncular pats on the back, was as full of livestock as Noah’s ark. There were the usual trusses of chicken, three Maniot pigs and a whole flock of goats. There was even a donkey with its foal. As though this were not enough, just as we raised anchor, a cicada, rashly flying a few yards out to sea, alighted on the gigantic white whisker of an old man who lay sleeping with his mouth open in a stertorous recurring semibreve. After a few seconds on this flimsy perch it struck up. The din, so close to the sleeper’s ear, must have sounded like an alarm clock. He broke off in mid-snore and leapt up beating his head while the insect went whirring inland to safety.

* * *

I shall fill the leisure of our journey up the gulf with a digression on cats and divers kindred themes.

Caiques often have pet cats on board and I have twice seen an important sailing held up—not that this takes much; anything suffices to postpone or expedite without warning the departure of these Bohemian barques—until the ship’s cat was hunted up among the rubbish and fishbones on the quay. A story told me by my old friend Tanty Rodocanaki[1] suggests that their presence is sometimes to be ascribed to more utilitarian reasons than pure cat-fancying. It seems that once upon a time a sea captain, distressed by the quantity of rats that infested his caique, summoned a priest and asked him to perform the special service for casting them out. The appropriate chants were intoned and the priest censed and aspersed the ship from stem to stern. Pocketing the usual fee, he assured the captain that he would have no more trouble with vermin: the rite had never failed yet. “But there’s just one point,” he said. “What’s that, Father?” The priest stooped his bearded head to the seaman’s ear and whispered: “Get a cat.” Since then the phrase “getting a cat” means, in maritime circles, making surety doubly sure.

Dogs are much less frequent members of a crew but you see them now and then. Once, during a hard winter storm between Samos and Chios, I heard barking through the thick mist. It grew louder till the mist cleared for a few seconds to reveal another caique dangerously near and lurching unsteadily among the great waves. A brown dog, with his forepaws on the bulwarks, was barking desperately into the storm. The mist soon obscured the other craft but I could hear the dog’s hallucinating protest for long seconds after it had vanished, growing fainter as the wind drowned it. Perhaps cats are better sailors.

Eastern European cats bear little resemblance to the ribboned pussies of the West. They are a completely different shape. The division runs roughly north and south through the Istrian peninsula. East of this line, their ears grow to the size, proportionately with their bodies, of bats; their bodies, their necks and their tails are longer. They are more alert, intelligent and enterprising, above all, wilder and distinctly more raffish. They are to be seen at their most disreputable in Constantinople, where the city pullulates with them. After dark these noble but sordid streets seem to move and writhe in the lamplight, an illusion induced by the criss-crossing itineraries of thousands of cats, sometimes alone, sometimes in little troops, all of them setting out on thousands of dark and questionable errands. Many of them have the air of broken-down musketeers with fractured noses, tattered ears and the equivalent of eye patches, their moth-eaten tails carried swaggeringly like long rapiers in worn-out scabbards. The Turkish attitude to dogs is one of contempt and hatred. It is well-known how they rounded up the myriads of dogs that once ran riot there and marooned them without food on an island in the Sea of Marmara until they had all eaten each other or starved to death. Their attitude to cats is different. They never kill them, nor do the Greeks, though both races expose unwanted kittens to die or to fend for themselves and survive as freebooters. So outlaw cats abound. I have heard this Turkish—or rather Moslem—forbearance attributed to a whim of Mohammed. The prophet was about to set off on a journey; rising, he found that a cat was asleep in a fold of his robe and, rather than wake it, he called for scissors, cut the cloth all round it and set off with a round hole in his cloak, leaving the cat still asleep.[2] The Greek attitude to dogs—some of the noisiest and often most frightening barkers in the world—is, like much of the Mediterranean, roughly affectionate, sometimes thoughtless and inconsiderate, seldom cruel. In some parts they have the quaint custom of calling them by enemies’ names in order to be able to speak sharply to them. I have often heard Cretans shout: “Come here, Achmet! Mustapha, be quiet! Boris—outside!” During the war they were called Mussolini, Benito, Ciano (a favourite bête noire of the Greeks), Hitler and Goebbels. Then it became Stalin, Gromyko, and Molotov. (Now, alas, perhaps Andoni or Selouin.) Cardinal Manning enjoyed scolding his butler, who was called Newman, on exactly the same principle.

The cats of Athens, like the citizens, are very intelligent. Just after the war I used to eat almost every night in an open-air ta-verna in the Plaka. One end of the garden was separated by a high wall from an outdoor cinema, and at the same moment every night, a huge black and white tom-cat stalked over the tiles to sit with his back towards us on this wall, intent and immobile except for the slow rhythmic sway of his hanging tail. After exactly five minutes he would saunter away again over the roofs. The waiter’s verdict on this procedure was obviously correct: “He comes for the Mickey Mouse every night,” he explained. “You could set your watch by him.”

In far-away islands each community develops with the centuries on slightly different lines; just as each island or isolated region puts forth various botanical species which are to be found nowhere else in the world. Crete, for instance, has over a hundred, and the small island of Hydra where I am writing these pages, two: the blue campanula tayloria which lodges in wall-crevices and the strange brown and butter-coloured Rodokanaki fritillary which grows high up the watershed. It must surely be the same with island cats, interbred for generations in steep un-cat-like habitats with only an occasional outside strain that comes to flower after the brief visit of some caique-dwelling tom. Certainly the two small animals crossing the middle distance as I write these words have little in common with any other kittens I have seen. It is not their markings—white with tabby patches like a sudden drift of mackerel sky on the face or flank—nor is it the engaging absurdity of the enormous bat-like ears, the wide kohl-rimmed eyes, the lean elegance and the bold carriage of their tails. They were found mewing desperately, their eyes just opened, and brought here to the walled and terraced seclusion of Niko Ghika’s house. Growing up without seeing or being corrupted by other cats they are Garden of Eden animals free of original sin and there is something peculiar and prelapsarian in their conduct. Stroking or fussing is uncongenial to them; they take no notice or walk away. But should one go for a walk they follow, but at a distance, as though their presence were fortuitous. The other day I found them both nibbling a cactus. The same evening I brought them the delicious remains of a red mullet wrapped in a newspaper. They sniffed the remains for a second, then went back to a slice of melon peel they had discovered somewhere; the fish remained untouched. They are as lithe as jaguars and their behaviour swings between almost lunatic activity and the loose-limbed stretching contortions of an odalisque, rolling over and over with all legs outstretched and suddenly falling asleep on their backs with their mouths open and their forearms wide apart and hanging like the flappers of capsized turtles.

Beyond the skimming gulls, the steep mountains of the coast followed each other southward with scarcely a village. I asked the captain if it was true about the seals at Egg Island, off Cythera. “Absolutely true,” he said, “tous vlépei kanéis na kánoun vengéra—na seirianízoun kai na perásoun tín óra tous”—“you see them hobnobbing and strolling about and passing the time of day.” This reminded me of a phrase I heard years ago when I asked Katsimbalis, before going there, what the Sporades were like. “Wonderful islands!” was the answer. “Skiathos! Skopelos! Skyros! The lobsters in Skopelos are the best in the world, and the biggest! They’re all over the place. Why, you see them walking up and down the streets and sitting down at tables—reading newspapers, playing tric-trac, ordering coffees and smoking narghilehs....” It was practically true. The first thing I met on landing in Skopelos was a young deacon carrying an enormous lobster under each arm, their slowly swivelling antennae covering so wide a span that they quite barred the narrow lane. But I have been unlucky with strange animals in Greece. Most of my contacts have been at one remove. I have never seen a wolf in Greece, though I arrived in Grevena years ago just after a party of Gipsies, trudging across the snow to play at a wedding, had been eaten to a man, little remaining except their boots and a hand clutching the neck of a fiddle with which its owner had obviously been laying about him as a weapon of defence. I once saw a wild boar on the Albanian border, one or two deer in Pindus, a bear never, though a few years ago, just after the civil war, an old Vlach shepherd in Samarina said to me: “Last year, when the hard fighting was going on up there,” he pointed to the surrounding peaks, “the bears all moved down into the valleys and villages. You met them everywhere. They couldn’t stand the noise, and I don’t blame them.” I think, but am not quite sure, that I have once caught a distant glimpse of an agrimi, the mad, shy, fierce, the all-but-invisible and nearly extinct ibex of the White Mountains in Crete. I have seen a landslide caused by its leap and I am deeply ashamed to say I have eaten a bit of one in the last tiny hamlet in the Samaria gorge. It was dark and gamey and incredibly good. A turtle I have seen only once, from the deck of a ship, floating languidly and then sculling steeply down into the blue-green depths between Bari and Corfu almost exactly at that point in the dotted line down the middle of the Adriatic where the filioque drops out of the Creed. I have once or twice seen the top half of their shells sliced from their base and, turned upside down, transformed into a cradle. One had a fisherman’s daughter asleep in it and very comfortable and decorative it looked. I have never seen a shark. They are extremely rare but they are, unfortunately, occasional visitors, following ships through the Suez Canal and straying into Greek waters. There was a terrible tragedy a few years ago—again, off Corfu—when a beautiful girl fell a victim to one, vanishing for ever on the eve of her marriage. But these monsters cannot be entirely due to the digging of the Canal. Solomos, the great Zantiot poet, wrote a moving elegy on the similar death of a soldier from the British garrison in those same Ionian isles. Fortunately, in spite of local scares, it no more stops people bathing than an occasional train accident stops travel. One never hears much about tunny in Greek waters; they seem to proliferate further west in the Mediterranean though their relation, the palamida, is not uncommon. In ancient times a special watchman, a thonoskopos, would keep vigil for tunny shoals on likely headlands and when his warning cry came the young men would run down to the boats with tridents and harpoons.

This journey seems vowed to zoological incident, for soon the delighted cry of “Delphinia!” went up: a school of dolphins was gambolling half a mile further out to sea. They seemed to have spotted us at the same moment, for in a second half a dozen were tearing their way towards us, all surfacing in the same parabola and plunging together as though they were in some invisible harness. Soon they were careering alongside and round the bows and under the bowsprit, glittering mussel-blue on top, fading at the sides through gun-metal dune-like markings to pure white, streamlined and gleaming from their elegant beaks to the clean-cut flukes of their tails. They were beautiful abstractions of speed, energy, power and ecstasy leaping out of the water and plunging and spiralling and vanishing like swift shadows, each soon to materialize again and sail into the air in another great loop so fast that they seemed to draw the sea after them and shake it off in mid-air, to plunge forward again tearing two great frothing bow-waves with their beaks; diving down again, falling behind and criss-crossing under the keel and deviating and returning. Sometimes they flung themselves out of the sea with the insane abandon, in reverse, of a suicide from a skyscraper; up, up, until they hung poised in mid-air shaking in a muscular convulsion from beak to tail as though resolved to abandon their element for ever. But gravity, as though hauling on an oblique fishing-line, dragged them forward and down again into their rifled and bubbling green tunnels. The headlong speed through the water filled the air with a noise of rending and searing. Each leap into the air called forth a chorus of gasps, each plunge a sigh.

These creatures bring a blessing with them. No day in which they have played a part is like other days. I first saw them at dusk, many years ago, on the way to Mount Athos. A whole troop appeared alongside the steamer, racing her and keeping us company for three-quarters of an hour. Slowly it grew darker and as night fell the phosphorescent water turned them into fishes of pale fire. White-hot flames whirled from them. When they leapt from the water they shook off a million fiery diamonds, and when they plunged, it was a fall of comets spinning down fathom after fathom—league upon league of dark sky, it seemed—in whirling incandescent vortices, always to rise again; till at last, streaming down all together as though the heavens were falling and each trailing a ribbon of blazing and feathery wake they became a far-away constellation on the sea’s floor. They suddenly turned and vanished, dying away along the abyss like ghosts. Again, four years ago, when I was sailing in a yacht with six friends through the Outer Cyclades in the late afternoon of a long and dreamlike day, there was another visitation. The music from the deck floated over the water and the first champagne cork had fired its sighting-shot over the side. The steep flank of Sikinos, tinkling with goat bells and aflutter with birds, rose up to starboard, and, close to port, the sheer cliffs of nereid-haunted Pholegandros. Islands enclosed the still sea like a lake at the end of the world. A few bars of unlikely midsummer cloud lay across the west. All at once the sun’s rim appeared blood red under the lowest bar, hemming the clouds with gold wire and sending a Japanese flag of widening sunbeams alternating with expanding spokes of deeper sky into the air for miles and spreading rose petals and sulphur green across this silk lake. Then, some distance off, a dolphin sailed into the air, summoned from the depths, perhaps, by the strains of Water Music, then another and yet another, until a small company were flying and diving and chasing each other and hovering in mid-air in static semicircles, gambolling and curvetting and almost playing leapfrog, trying to stand on tip-toe, pirouetting and jumping over the sinking sun. All we could hear was an occasional splash, and so smooth was the water that one could see spreading rings when they swooped below the surface. The sea became a meadow and these antics like the last game of children on a lawn before going to bed. Leaning spellbound over the bulwarks and in the rigging we watched them in silence. All at once, on a sudden decision, they vanished; just as they vanish from the side of the Aphrodite in this chapter, off the stern and shadowless rocks of the Mani.

“Kala einai ta delphinia,” the captain said when they had gone. “They’re good.”

Mythology and folklore are full of tales about dolphins. They all revolve round their benevolence, their love and solicitude for man. It is well-known how Taras, saved from drowning by a dolphin, lived to found the city of Tarentum: the manner of his rescue is immortalized on Tarentine coins. Between Corinth and Syracuse, Arion the lyre-player was rescued from death at the hands of predatory sailors by a troop of dolphins that had gathered round the ship to listen to his playing. There are heartrending tales of dolphins falling in love with mortals and attempting to join them on land, dying by cruel misadventure and changing, in their death throes, through all the colours of the rainbow.[3] Their passion for music was queerly illustrated a few years ago. A friend of mine, Dr. Andrea Embirikos, the psychiatrist and poet and a member of the well-known ship-owning dynasty, was rowing peacefully in a boat one afternoon off the coast of his native Andros, listening to a concert on the small portable wireless he had placed on the bench in the stern. After a few bars, half a dozen dolphins appeared from nowhere and began to swim quietly round the boat. Soon, however, carried away by the crescendo they grew more boisterous and leapt out of the water, banging the side of the boat and even attempting to join him on board. The boat rocked dangerously and Andreas hastily picked up the wireless lest it should be knocked overboard and put it under his arm—it was one of those sets that switch off automatically when the lid is closed. Almost at once the dolphins disappeared and all was calm. A few minutes later he opened the set again and an identical scene took place. Finally he was forced to row to land and finish the concert among the rocks, under the reproachful gaze—at a safe distance now—of his would-be companions.[4]

I was told, for what it is worth, another queer tale, the same year, of a sailor who fell overboard between Crete and Santorin. He was a bad swimmer, and when he was tired out and about to sink to the bottom he felt something large and smooth thrusting between his exhausted and water-treading legs: his knees were being separated by the back of a surfacing dolphin bent on saving him. Soon he was being carried along at a gentle pace by the kind mammal and after a while, afraid of losing his seat, he wrapped his arms round his saviour’s neck. But in a few seconds his mount became as stiff as a plank, and rolled over with its white belly in the air, unsaddling the sailor, who had unwittingly blocked the dolphin’s blow-hole with his forehead and killed it stone dead by suffocation. But the man’s feet touched bottom and he was saved....

Similar tales abound....

Could they have any connection with one of the most notable mentions of the species and one of the strangest scenes in mythology? Once, when Dionysus had hired a ship to carry him incognito from Icaria to Naxos, the crew, a band of conspiring Tyrrhene pirates of the same feather as Arion’s malefactors, altered course to Asia to sell the god as a slave. The god changed himself into a lion and the mast and the oars into serpents and entwined the ship with a sudden network of ivy and filled the air with the sound of flutes. Mad with terror, the pirates leapt overboard and, changed into dolphins by the god, swam bewildered away.... Could this account for their obsession with music and their age-old courtship of mankind to which, before their metamorphosis, they belonged? Their kindness to mankind might be a protracted atonement for their past harshness and impiety....I don’t think so. They seem too transparently good to have been villains in a previous life....

The captain was pleased, because they bring luck to a ship. He leant contentedly on the blue and white striped tiller flicking his tasselled chaplet of amber beads over and over between his index and middle fingers.

“They are strange fish,” he said. “Some sailors know how to summon them. If they see them swimming in the distance, they shout ‘Vasili!’ in a special way they have. The fish stop dead, standing upright in the water, looking round to see who has called. When the sailor shouts ‘Vasili’ a second time, they join him like lightning. They all have the same name.”

So they are all called Basil. Is there a link missing, a lost anterior fable that connects them with basileus, or King, from which the word derives?

“I’ve never seen it done,” the captain admitted, “but I’ve often heard of it. They have a special way of shouting....”

* * *

The watershed of the Taygetus climbed steadily, and its retreat inland indicated that the Mani was growing wider. It rose in a sierra as desolating as a dirge. Lolling satrap-like among the corn-sacks, we watched the dry ravines succeed each other above the restless jungle of goats’ horns. The captain gave an occasional shift to the tiller and shouted an order and then continued humming to himself.

* * *

Most of these orders and many maritime terms in Greece are of Italian origin, in the same way that so many English sea terms, though to a lesser degree, are Dutch. They are a legacy from the Venetian maritime empire. The same nautical lingua franca holds good, irrespective of nationality, from the Pillars of Hercules to the Red Sea and along the southern Euxine coast as far as the Caucasus. The Greek Laska! is Lascia!—“pay out rope,” or “let loose.” Founda! is “let the anchor drop to the bottom!”

Vira! is “haul in,” with the suggestion of twisting a winch. Ka-rina is keel, bastouni bowsprit, albouro mast; and so on. Time has distorted many of them. I can never hear these orders without a momentary glimpse of a many-oared galleon slave-propelled under a crimson gonfalon charged with the gold lion of St. Mark.

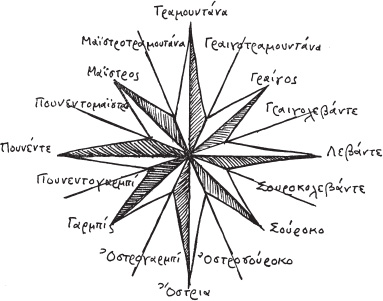

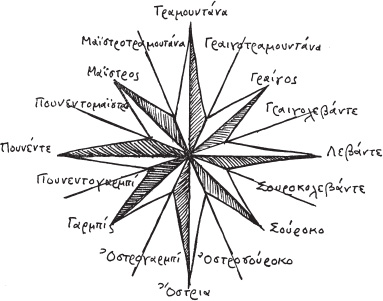

The winds have nearly all changed their names and they too whisper a garbled echo of the long-dissolved Venetian power. The north wind is the Tramountana, though the ancient Boreas, one of the very few of the winds that Odysseus kept tied in a bag, still survives as well. Ostria, the south, in the Latin Auster, though the ancient Notos is still sometimes used. Levante is the east wind and Pounente the west. N.E. is Grego, the Greek wind, S.E. the African Souróko, S.W. the Arabian Garbís, and N.W. the Mäistro, or Mistral. The heart of this wind-rose seems to be somewhere off Sicily, the heart of the Mediterranean in fact. The subdivisions—N.N.E., E.N.E., E.S.E., S.S.E., and so on—are a string of euphonious composite words: Gregotramountána, Gregolevánte, Sourokolevánte, Ostrosoúroko, Ostrogarbí, Pounentogarbí, Pounentomäistro, and Mäistrotramountána. The words Euros—sometimes called Vulturnus by the Latins, the wind that oppressed the banished Ovid in the Tristia—and Zephyros can still be used in the high-flown language to designate the east and the west winds, and the ancient Lips, the south-westerly Libyan wind, survives as Livas. Homer only mentioned the four cardinal winds. The four beastlike winds—Typhon, Echidna, Chimaera and the Harpies[5]—have decamped from the Greek air for good. Mpátis (from embainein, to enter) is a cool breeze coming in from the sea, drawn there at midday by the growing heat of the earth and rocks to fill the void of the rising hot air. Apógeios—quite literally “off shore,” or rather “off land”—is the opposite phenomenon. The liquid sea warms and cools more slowly than the mineral land—like tea and teaspoon—and so between sunset and about ten at night, the track of the morning Mpátis is reversed. It blows for a few night hours until the temperature of earth and sea are equal; then the vagrant airs are still. The ancient Etesian winds which blow through the summer months can be a blessing or a curse: they cool the archipelago but drive caiques off their course or lock them in harbour. They are a Mpátis on a giant scale, a wind that rushes south across the Mediterranean to fill the airless ovens of the Egyptian and African deserts; which repay them, now and then, with a long dragon’s breath of sirocco. This wind is now called the Meltém which philologists derive from the Venetian bel tempo because it only blows in summer. When the Meltémi blows hard the inhabitants of the island of Spetzai called it Trapezókairos—“table weather”—because one gust of it will capsize all the café tables along the harbour. Except that it was too late in the year, this could have been the “tempestuous wind called Euroclydon” that gave St. Paul’s ship such a rough time south of Crete, when the last chapters of The Acts turn into an Odyssey. But “neither sun nor stars in many days appeared,” so it was winter. Euroclydon is called Euraquilo in the Vulgate, a north-easter. It was Notos, the south wind (Auster in St. Jerome’s text), which till then had been blowing so softly. How well I remember, during the war, gazing from caves on Mount Ida to “the island called Clauda” under which they ran so close (it is Klauda or Kauda in the Greek testament, Gavdos in modern Greek). The only Western traveller to describe this islet in recent times is an old friend and brother-in-arms from those peculiar years.[6] Anyone who has tried to land on that coast from a small boat will appreciate the apostle’s difficulties. The Levanter, the strong east wind that blows across the Adriatic, had a deep influence on ancient Greek history. Rather than confront the fierce weather that lay further up the long gulf, Greek emigrants avoided the Adriatic coasts. Following the prevailing wind, they were scattered like grain over southern Italy, Sicily, the coasts of Provence and even southern Spain, and flourishing Greek colonies sprang up there while the coasts north of Epirus and Illyria, so much nearer home, remained practically unknown.

Caique sailors are for ever peering at the surface of the sea like joiners studying the grain of a piece of wood to see what ripples or markings the wind makes and murmuring “garbis,” “maïstro,” or “sourokolevánte,” and predicting bonatza, fair weather, or, with gravely shaking heads, phourtoúna, a storm. (In Crete, foul weather is called cheimonas—winter—even if the season is midsummer.) The air in Greece is not merely a negative void between solids; the sea itself, the houses and rocks and trees, on which it presses like a jelly mould, are embedded in it; it is alive and positive and volatile and one is as aware of its contact as if it could have pierced hearts scrawled on it with diamond rings or be grasped in handfuls, tapped for electricity, bottled, used for blasting, set fire to, sliced into sparkling cubes and rhomboids with a pair of shears, be timed with a stop watch, strung with pearls, plucked like a lute string or tolled like a bell, swum in, be set with rungs and climbed like a rope ladder or have saints assumed through it in flaming chariots; as though it could be harangued into faction, or eavesdropped, pounded down with pestle and mortar for cocaine, drunk from a ballet shoe, or spun, woven and worn on solemn feasts; or cut into discs for lenses, minted for currency or blown, with infinite care, into globes. On top of this, all the nautical wind-talk and scrutiny of the elements fills it with innumerable unseen coilings and influences and cross currents and comings and goings. It is no wonder that the Greek word for wind—anemos—should have produced the Latin word anima, for soul; that pneuma[7] and spiritus should mean spirit and breath and wind in both languages. Perhaps it is not strange that the age-old Greek war-cry—the equivalent of St. George!, Montjoy-Saint Denys!, and Santiago!—should be the single word Aera! which means both wind and air.

There is, in fact, more in the air than meets the eye. The element is further complicated by the presence of ta aërika, the spirits of the air. They have cropped up earlier on in these pages. They are less of a problem to present-day sailors than they used to be a few decades ago. But there is a subdivision of the species of daemons, or genii, of the air which has an immediate relevance to sailors. They are known as ta telonia: the customs offices and, by extension, officers. Popular fancy has created a whole hierarchy of hovering excisemen through which the soul has to pass on its way to Paradise or to Hades. Soaring souls are examined by invisible douaniers who scrutinize their psychic luggage for unatoned sins, both deadly and venial. Tradition has degraded them from their severe but benign status to the rank of evil harm-wreaking spirits whom the corpses—or their flying spirits—can placate with a coin that may, alternatively, have been placed in their mouths either to placate Charon or to block, with their metal barrier, the ingress to other evil spirits. Shooting stars, comets and other celestial portents are considered manifestations of ta telonia. These affect—or used to affect—all mortals; but the customs-phenomenon most dangerously and specifically aimed at sailors is St. Elmo’s Fire. This sinister light flickering and shuddering about the mast and the yards of a caique foretells with certainty the onslaught of these baleful air-denizens. Exorcism and incantation used to be effective antidotes, but the surest way of all—like the remedy against the Lamia of the Sea when she appears in the form of a waterspout—is to stick a black-handled knife into the mast, if possible after it has been used for cutting an onion. The reek aroints the air. In ancient times, two such airy manifestations were considered propitious; they were the Gemini, protectors of seamen. A single flame, however, betokened their sister Helen whose fatal beauty wrecked towns and ships and lives.

Seamen peer into the sky at night not only to steer by the stars but to prognosticate the future from the tilt of the crescent or decrescent moon. “Orthio to phengári,” they say, “xaploménos o kapetánios’: if the moon is upright, the captain can lie down. If the incomplete moon is lying on its back, the captain stands to the helm; it foretells phourtoúna: “Xaploméno to phengári,” in fact, “orthios o kapetánios.” They are great ones for steering by their fingers—holding up a hand at arm’s length to measure off one, two, or three fingers’ breadth from a cape or a rock and moving the rudder accordingly. I once heard an old ocean-going sailor describing, only half in fun, between puffs at his narghileh, how to sail from the Piraeus to London entirely in such terms. “When you get to Cape Malea,” he said, “aim three fingers to port of Matapan, a finger to starboard south of Sicily, two to port at Cape Spaptiventi in Sardinia, one to starboard at Gibraltar, three at Cape St. Vincent, two at Finisterre, two more at Ushant...why a baby could do it... Then four to port at Margate, follow the Thames upstream, drop anchor at Tower Bridge, then go ashore and order a beef-steak. Na!...”

We rounded a small cape. A valley full of scarcely believable green trees appeared and a mile or so up the mountain, a towered village. A busy little port sheltered half a dozen caiques. “We’ve arrived,” the captain said. “Kotronas,” he announced and then, pointing uphill at the towers, “Phlomochori.” Alongside the mole a few minutes later we heard his voice cry “founda!” and down went the anchor with a clatter and a splash.

[1] Alas, he died last year, a sad loss to his friends everywhere.

[2] I have heard, on equally uncertain authority, that the Turks have a superstition about storks and never shoot them. They are now jealously preserved in Greece, but apparently it was not always so. Many thousands of storks spend the spring and summer in Greece, but none of them nest south of a line running south of Epirus and Thessaly from the Ambracian Gulf to the Gulf of Volo. This was roughly the Greek-Turkish frontier until the first Balkan War in 1912, when the Greeks captured and retained all of northern Greece which is now the storks’ chief habitat. It must have been about then that the laws protecting them came in. Storks have proverbially long memories, but (if this story is true) I hope they will let bygones be bygones and return to their old haunts in Roumeli and the Peloponnese; old prints show that they were common in Turkish-occupied Athens at the beginning of the last century. They are unknown there now. Their nests and their graceful flight ennoble the humblest village. A strange example of traditional fear among migrating birds comes into Alan Moorhead’s Gallipoli. A vast column of duck and other birds flew over the Dardanelles at a moment of total deadlock in 1916. Exasperated by inaction, the two entrenched armies opened upon them with all they had. It was a massacre and the birds avoided the baleful straits for many years after.

[3] See Norman Douglas, Siren Lands, and Lord Kinross’s Europa Minor.

[4] This happened in Batsí Bay, off the western shore of the island.

[5] The harpies have settled in the two desert islets of the Strophades. I shall have much to say of these bird-winds in another book. See the Æneid, bk. III.

[6] See The Stronghold, by Xan Fielding (Secker and Warburg).

[7] The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola can be exactly paraphrased as Pneumatic Drill.