I am writing these pages in the United States, certainly the biggest producer of apocalyptic images in the world. America is the place where the genre its French fans call “apo” has flourished. You can feel it on every street corner; imagery of the end is everywhere.1

Yesterday, February 13, 2012, I bought the most recent edition of that indescribable weekly rag called Sun Magazine (not to be confused with the respectable monthly The Sun). Under the gaudy name of the newspaper, if one gets close enough to make out the small print, one can read: “God Bless America®.” But what drew my attention as I was waiting in line at the supermarket cash register (oh, the supermarket! that postapocalyptic place par excellence, the topos of survival …) was the main headline on the first page: “New Mayan Prophecies Reveal … End Times Begin On Valentine’s Day.” The apocalypse, as the reader I am is meant to deduce, is for tomorrow. Or rather, tomorrow, it will start being prepared.

This extraordinary bit of news is developed over a double- spread inside page. Under a hill in Georgia, a team of archaeologists is said to have exhumed a Mayan pyramid on a site that is said to be that of the mythic city of Yupaha, the very one the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto was looking for in 1540. Sic. I rub my eyes. But wait, that’s nothing yet: In the pyramid has been found a stone calendar that measures time in long cycles of 63,123,288 years. Nothing less. And, get ready for it, a writer and explorer by the name of Beverly Neeson, who is interviewed in the article, explains that there is a mistake: The famous apocalyptic predictions for December 21, 2012, she says, are based on an erroneous interpretation of the Mayan calendar, for the engravings in the stone indicate that the End Times will begin … starting tomorrow, February 14, 2012. At which point we will see (citing randomly) that Iraq has nuclear weapons, that tsunamis will flood Japan and other countries in Asia, that extinct volcanos will erupt all over Europe, that fires will ravage Africa, that huge tornados will streak through the United States. But in the fall, Jesus will appear throughout the world to bring all this suffering to an end with his message of hope and salvation.

I swear I have invented nothing; it’s all printed in black and white. And this kind of story populating the pages of celebrity and gossip magazines is also the matrix of blockbusters such as Roland Emmerich’s 2012, released in 2009. We need to pay particular attention to these “disaster movies,” a kind of attention they are not really paid when one stops with a gloss on the plot, the supposed ideology, distribution and reception, the box-office returns …

But before watching 2012 and other productions like it, let us lend an ear simply to that title. Let us try to hear what is housed in this date that, like so many dates, is part of the vast filmic archive of the ends of the world: To mention only films I’ll be discussing, we might think of 2001 (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) and its sequel 2010 (Peter Hyams, 1984), of Escape from L.A. (John Carpenter, 1996; French release title Los Angeles 2013), A Boy and His Dog (L. Q. Jones, 1975; French release title Apocalypse 2024).2 … How many dates will have been inscribed onto the screen if we include all the ones that, without making it into the title, are embedded into the image over the course of the narration? “Early in the 21st century” are the first words at the start of the scrolling text that opens Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982). And in the exposition that precedes the opening credits of 2012, one sees many inscriptions of place and date that note the signs from all over the globe that together announce the catastrophe: Copper mine in Naga Deng, India, 2009—Lincoln Plaza Hotel, Washington, 2009—G8 Summit, British Columbia, 2010—Cho Ming Valley, Tibet, 2010—Empire Grand Hotel, London, 2011—Louvre, Paris, 2011 … , a sequence that continues to accelerate right up until the moment when the title itself appears, 2012, but this time without any localization: 2012 is the date tout court, the nunc without hic, the fatal year. Finally, a reporter on TV explains that the huge collective suicide discovered in the ancient city of Tikal in Guatemala was motivated by faith in a Mayan prophecy that the world would end on December 12, 2012.

12–12–12: Here the date seems to be nothing more than its abyssal repetition. As we will see in a moment, a date is always carried away into its own commemorative whirlwind. This is why, in fact, a date remains essentially yet to come; it is that infinite approach to itself through which it tends to meet itself, to coincide with itself by going down in history [en faisant date].

In other words, a date is a countdown to the now it will always have been in advance. It’s a countdown apparatus like all the chronometers that measure the time that remains, starting with the Mayan calendar brought up to date through today’s fashion for the new age and ending with the Doomsday Clock, where the minutes separating us from the apocalypse—whether nuclear or otherwise—appear, and including millenarian countdowns like the one we see at the end of Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995).3

Images of a deserted city scattered here and there with cadavers, on the sidewalks, in a doorway, on the stairs. The blackboard of a community church bearing the white letters of an inscription: “The end has come.” The camera enters through the broken window of the house of Doctor Morgan (Vincent Price). The alarm goes off. The doctor stretches and gets up—it’s the beginning of the story told by a voice-over. “Another day to live through. Better get started.” After a prelude that is silent until these two phrases are pronounced, the opening credits start to roll, and the narrative also seems to shake itself awake and stretch, with difficulty, as the protagonist drags himself, bent over and tired by his job as it starts up again, by the labor that consists merely in continuing to survive.

We follow the doctor into the kitchen where he finds himself in front of the page of a calendar. “December 1965,” his voice comments, slowly. And the camera pans down the wall where we see other dates scribbled in, 1966, 1967, months, March, April, May, grids made up of squares checked off every day, day after day. “It’s only been three years,” he continues, “since I inherited the world.” Another piece of the wall. 1968, January, February.… “It feels like a hundred million years.” He crosses off the square for September 5. He takes off the plank that locks the door from the inside. And goes out.

The Last Man on Earth (Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow, 1964) is the first film adaptation of Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend. Every day in it seems like every other, each night like each night. Passing time passes only like the needle of a phonograph that, in the morning, when the vampires have disappeared, skips and gets stuck in the last empty groove of the record that the doctor, as he fell asleep, left turning around and around. “Another day,” he says to himself as he awakens yet another time, “another day to start all over again.” Every day, Robert Morgan, the last man on Earth, thus seems to put the counter back to the beginning. Every day, he does what in astronautics is called a count-up that starts from nothing. He has to start it over every time, as if the night had erased everything; he has to repeat the same ordeal of getting going again.

Every afternoon, in fact, as the evening and sunset draw closer, the doctor’s time is counted. According to a countdown that in this case threatens to be fatal, since nighttime is the realm of the contaminated who are on a search for the last healthy representative of the human species.

Yet the time of this countdown toward nightfall is also, quite precisely, cinema’s time. In the second adaptation of Matheson’s novel for the screen, The Omega Man (Boris Sagal, 1971), this is in effect the time that Colonel Robert Neville (Charlton Heston), the sole survivor of a bacteriological war, takes for himself. It is this counted time he gives or allows himself to take in a movie. After having driven through a Los Angeles that has turned into an urban desert, he thus stops at the end of the day in front of a theater that is advertising—and has been “for three straight years,” he mumbles—Woodstock, Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 documentary. He enters first into the projection room where he has to start up the electric generator and then the projector before he can enjoy the show from a seat. He knows the songs and dialogue by heart, to the point that he repeats them, murmuring and whispering them in improvised and solitary dubbing. “Great show,” he had ironically said as he entered the movie theater. And before leaving the theater to go home as long as there’s daylight, “Yeah, they sure don’t make movies like that anymore.”4

When he leaves, it’s late. We can just barely make out the last rays of a setting sun. Robert Neville has probably not seen the film all the way to the end. And it’s a good thing, too, for if he had allowed himself to be taken away by the movies, if he had entered into the world of the screen, he would have truly run the risk of being given over to the vampires, the living dead who, at nightfall, wander through L.A.

He barely escapes them on the way home. He is able to kill off a few and to defend himself from another’s assault. Going up in the elevator to his fortified apartment, he remembers. He recalls the events that led to the end of the world. And what starts this other projection—his memory’s, the film of his memories—is his finger pressing the button for the top floor. The colonel’s index finger seems both to start the projector of images from the past and to launch the missiles, the bacteriological bombs of world conflict.

It is said that the countdown was invented at the movies. By Fritz Lang in Woman in the Moon (1929).5

Before, the procedure happened in increasing order, as one sees in the famous launch staged by Jules Verne in 1865 in From the Earth to the Moon at the end of chapter XXVI called “Fire!”

Only forty more seconds, and each one of them was like a century.

At the twentieth second a quiver ran through the crowd and everyone realized that the daring explorers inside the projectile were also counting the terrible seconds. Isolated cries broke out:

“Thirty-five! … Thirty-six! … Thirty-seven! … Thirty-eight! … Thirty-nine! … Forty! … Fire!!!” …

Instantly there was a terrifying, fantastic, superhuman detonation which could not be compared to thunder or any previously known sound, not even the eruption of a volcano. An immense spout of flame shot from the bowels of the earth as from a crater. The ground heaved, and only a few people caught a brief glimpse of the projectile victoriously cleaving the air amid clouds of glowing vapor.6

As far as Fritz Lang’s film is concerned, it is placed completely under the sign of the countdown, since it opens with this epigraph: “For the human mind, there is no never—at the most a not yet” (Es gibt für den menschlichen Geist kein Niemals, höchstens ein Noch nicht). But of course it’s for the scene when the rocket takes off that the director inaugurates the procedure that will leave such a major mark on so many films, apocalyptic or not.

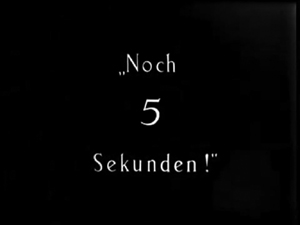

“Sixty more seconds,” announces an intertitle once everything for the launch is in place. Stretched out on their seats, the astronauts are waiting with a tense gaze, their hands ready to activate the control sticks. “Twenty more seconds,” “Ten more seconds.” … And then something incredible happens, something perhaps unique in silent film: The intertitle is animated: The frame of the sentence stays the same— “…more seconds!”—but the numbers inserted into it decrease as their size increases …

… until what we see, in huge capital letters that fill the entire screen, is absolute presence, the parousia of the cinematographic event.

“Now,” says the film—and an intertitle has no doubt never been so simply, so extremely performative, even as it does nothing more than designate the moment: this one, this photogram.

That is to say the one that will immediately follow. Because this absolute deictic, like a stretched cinematographic index finger that aims at the pure presence to itself of the image on the screen, is at the same time the filmic gap—however tiny it may be—between this image here and the other one.

But it is not only in film that, starting with Fritz Lang, we count down this way: Another countdown inhabits and haunts the history of film, the one that happens each time before the film, as its preparation. The decreasing numbers—what Americans call the “academy leader” or the “countdown footage”—measure the time remaining before the film itself properly begins.

Before the film and within the film, then, we count down. And once the end finally arrives, the parousia of the much-expected great now (jetzt) immediately collapses into deferral, into the adjournment of the image to come, the following one, the next one.

The distance that opens at the end of the countdown—but also, already, in each one of its digits, in each one of its stations—is the paradoxical time of apocalypse-cinema. The time, perhaps, of film itself, insofar as it could be said to be always on the threshold of its end.7