“Doom!” exclaims D. H. Lawrence when he finishes his mad reading of Melville’s novel Moby-Dick.1 The word returns two, three, four times in a row, like a death-knell for a drowned world:

Doom! Doom! Doom! Something seems to whisper it in the very dark trees of America. Doom! (153)

To read doom as loss, condemnation, or ruin would not be enough. The end of the world (doomsday) resonates in this dismal word: It’s the apocalypse. “Doom of what?” asks Lawrence. What is condemned? What is this world that is in the midst of finishing and being swallowed up by the whirlpool where the whaling ship is sinking in the epilogue to the chase for the white whale?

The vessel that sinks through its bottom, carried away by the hunting madness of Captain Ahab, the Pequod, is a kind of prefiguration of the Titanic.

The Pequod went down. And the Pequod was the ship of the white American soul. She sank, taking with her negro and Indian and Polynesian, Asiatic and Quaker and good, business-like Yankees and Ishmael; she sank all the lot of them. (147)

Beyond the vocabulary of races and types that have become intolerable to our ears today (Lawrence’s text was written between 1918 and 1923), one must understand that what is sinking here is the West, launched at a frantic pace into a mad quest for self and taking the whole world away with it. What then, Lawrence wonders, is Moby-Dick? What is this whale as white as what he calls the “white race”? It is “us,” he answers:

In this maniacal conscious hunt of ourselves we get dark races and pale to help us, red, yellow, and black, east and west, Quaker and fire-worshipper, we get them all to help us in this ghastly maniacal hunt which is our doom and our suicide. (146)

“Boom!” exclaims Lawrence, as if he were punctuating his description of the general shipwreck with an onomatopoeic deformation of the end of the world (“doom”). It’s all over and consummated (“consummatum est!” he writes in Latin), it is all consumed; the only things left are a few scattered remains:

Moby Dick was first published in 1851. If the Great White Whale sank the ship of the Great White Soul in 1851, what’s been happening ever since? Post-mortem effects, presumably.

It has, therefore, already taken place, this apocalypse to which Lawrence, before dying, will devote a posthumously published study in 1931.2 It has already happened. And we, whoever we are, are its fallout.

This is a gripping vision, which nonetheless misses a crucial aspect of the end of the novel, and for good reason: The edition of Moby-Dick Lawrence seems to have used omitted the epilogue. That is, the moment when, in the overall wreck of the ship-West, in the maelstrom that takes everything and everyone away, a bubble is created, a bubble as black as ink (“black bubble,” writes Melville), which by bursting liberates the buoy-coffin thanks to which the narrator Ishmael will, like someone living dead, be able to survive and start to tell the story at the very moment it ends.3

In short, the final catastrophe of Moby-Dick is, in the same double blow, both apocalyptic and postapocalyptic: What there is after the end of the world (of the book) is still and more than ever before part of the book (of the world); the bubble of ink for which room is made in the writing bursts by opening onto an outside that is within, which is only a swelling, an internal bulging within the great whale-text. Whose world does not lead to any backworld or otherworld: Rather, it is constantly making room within itself for bubbling interworlds.

Alongside John Huston’s 1956 adaptation, Moby-Dick does make several one-time appearances in the margins of apocalyptic films. I’m thinking in particular of 2012, where we get a glimpse of the book placed facedown to keep it open to the right page on the sofa in the room where Jackson Curtis wakes up late to go get the children, while the world starts to feel the first seismic tremors announcing the end. In the same way, in Deep Impact (yet another variation on the theme of interplanetary collision orchestrated by Mimi Leder in 1998), the astronauts charged with the task of making the comet explode on its way to the Earth fail in their mission and, having lost all contact with our planet, pass the time by reading the famous incipit to Melville’s story (“Call me Ishmael”).

But you will have understood that it is not a matter of hunting down the literal occurrences of the novel on screen. The question that awaits us is, instead, what is the status of the bubble in film? Is there a cinematic place for this enclave that takes on the form of an internal swelling? In other words, even as the cineworld sinks itself, does it not reserve within itself a space where its end might be said, shown, and filmed?

In English, a “blob” is a synonym for a “bubble.” And this old onomatopoeic word—which according to the Oxford English Dictionary appeared in the fifteenth century to express the action of lips that produce a bubble—is also the title of a cult film that was followed by two remakes: The Blob (Irvin Yeaworth, 1958), Beware! The Blob (Larry Hagman, 1972), and The Blob (Chuck Russell, 1988). The blob in question is a substance of extraterrestrial origin that develops, spreads, and grows by absorbing the living earthly beings whose path it crosses. It ends up being contained when the terrorized inhabitants of the little town where it started to run rampant discover that it cannot tolerate low temperatures. Add to this the fact that its gelatinous matter becomes increasingly red as it swallows a growing number of good Americans and you have all the ingredients to conclude that the plot is a metaphor for communism and its containment by the so-called Cold War.4 Whatever its necessity may be, it is not a socio-historical reading like this one that will retain us here. What interests me is rather that, in the successive versions of its expansion, the blob always ends up happening, quite literally, to the movies.

In the 1958 film, when Steve (Steve McQueen) and Jane (Aneta Corsaut) decide to ask for help in order to try to capture the formless monster that has just swallowed several of their fellow citizens, they go to find their friends in a local theater where the movie Daughter of Horror is playing (the abridged version of Dementia, directed by John Parker in 1953). The small group leaves the showing and sets off on a quest for the evil substance. After several twists of plot, including a memorable scene among the pieces of meat hanging in a supermarket freezer, the blob finds itself in the projection booth where the projectionist is reading while the projector hums. Through the air grates, we glimpse something glowing, something moving. And then the viscous red paste is disgorging and slowly pouring itself out into the room, while the audience is having fun, captivated by the horror flick that keeps playing.

The poor projectionist is swallowed up, and the reel stops. Perplexed, the spectators see a few strips of film and then find themselves facing a white screen while the substance now seeps through the booth’s windows and little by little invades the theater. A sea of humanity then rushes out of the movie theater screaming with terror, soon followed by the blob itself, growing ever redder. And ever more engulfing.5

In the 1988 remake, the blob—which this time is presented as a mutant virus, the fruit of an experiment in bacteriological warfare carried out by the United States in extraterrestrial space to ensure its military superiority over the Russians—also invades the movie theater where an (uncredited) horror film is playing. Here too, it infiltrates through the channels of the air-conditioning system, devours the projectionist, and spreads from the booth into the theater. Screams emerge from all over; we no longer know if the shrieks come from the spectators or from the characters in the film within the film. Then the sound stops; the reel seems to be covered with white blisters before turning completely red. Once again, what the blob engulfs is cinema itself.

Irvin Yeaworth, dir., The Blob, 1958

The 1958 version ended with a traditional THE END, whose white letters were nevertheless deformed to compose a menacing question mark, leaving doubt as to its veritable conclusion. To Lieutenant Dave (Earl Rowe), who was explaining that the Thing was going to be sent to the North Pole and that it would be contained there even if it could not be eliminated, Steve had effectively just answered, “As long as the Arctic stays cold.” This is indeed the starting point for the 1972 remake, which, therefore, presents itself more as a sequel, since everything starts over again when a worker on an oil pipeline in a polar region returns home to Los Angeles with a sample of permafrost he is supposed to keep cold. He allows it to defrost, and here we go again: The blob is back; it snacks on a fly, a kitten, and then the negligent worker himself, while on television he is watching … the 1958 version of the film. It is the young Bobby (Robert Walker Jr.), who, at the end, will once again be able to contain the gelatinous expansion by activating the refrigeration mechanism of the ice-skating rink where he finds himself trapped. But when the local sheriff, posing triumphantly on the frozen blob, gives an interview to a television crew, the spotlight lighting the filming inadvertently heats up part of the snowy mass. A red trickle starts to ooze toward the boot of the one proudly speaking to the camera: “If we hadn’t stopped it, this blob could have devoured America, maybe even the whole planet,” he says, before the same fateful question from 1958 is displayed on the screen—THE END?

This is indeed what is at stake: It is indeed its end that, once again, cinema is interrogating by staging this matter whose consistency so resembles the melted reels of a film. Awakened from its numbness by the shooting lights, the blobulous bubble promises to engulf everything, to emblob the film itself. It is like a blister or swelling of the film, a vesicle secreted by the cineworld which, in return, threatens to cover it up, to enclose it by including it. In sum, the blob is this overflow, this too-much of cinema that is unleashed in the movies where it appears like the excess of itself that prepares the blinding fusion of a general fade to red.

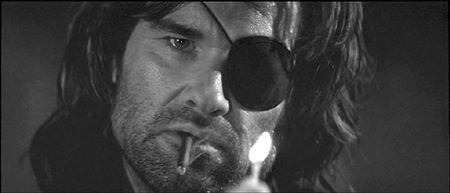

If one looks closely enough, it is also a cinebubble, the same one but another, that is formed and bursts at the end of John Carpenter’s Escape from L.A. In the year 2000, recounts the off-screen voice of the prologue, an earthquake of unprecedented magnitude has separated L.A. from the rest of the continent, thus transforming what the American president (Cliff Robertson) describes as the “city of sin” into an island to which criminals are being deported. Sixteen years after his heroic intervention in Escape from New York—to which Escape from L.A. thus provides a sequel—Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), described as the most famous outlaw in the history of the United States, receives a proposal for a pact that looks like blackmail: His crimes will be pardoned and he will escape certain death if he is able to find the remote control seized by a terrorist organization that is preparing to activate the satellite defense system, allowing for the extinction of all the planet’s sources of energy. The exposition of the plot, the moment of the contract with the hero, comes dangerously—or ironically—close here to the worst jargon of futurist war, both naïve and tortuous.

But this is not what is important. What must instead give us pause is first of all the role holograms play in the film. When the president and the officers from the army present Plissken with the terms of his mission’s contract, which he will not be able to refuse, they do so in effect through the intermediary of their holographic projections. The hero notices this when he tries to attack them: He goes right through them, barely disturbing the emission of the video signal. But the holographics that protect the blackmailers will also protect Plissken, who finds himself bestowed with a camera with which he will be able to generate an image of himself. It can be used only once, he is told, so he will have to save his hologram of himself for the moment when he really needs it.

After all these long preparations, Plissken is propelled into L.A. in a one-man submarine, a kind of filmic capsule in which he enters the cinema-city par excellence. After many adventures that are often open confrontations with the film industry,6 the hero ends up recovering the apocalypse’s remote control, the object capable of taking the Earth back several centuries, to before the invention of electricity. And of course also before the invention of holography or cinematography.

To escape his execution by the president and his men (who apparently have no intention of respecting their contract), Plissken activates, for the first and last time, his hologram. And during the respite provided by this filmic double of himself, he starts up the apparatus that will bring the planet back to the Middle Ages. “He did it!” exclaims the president’s daughter; “he shut down the Earth!” Plissken’s hologram also shuts down, and everything is plunged into darkness. But before the end of the cineworld, the hero allows himself one last cigarette (brand: American Spirit). He lights it with a good old match, which becomes something like the last glint, a fragile light to guide us in the eternity of acinema.

John Carpenter, dir., Escape from L.A., 1996

A close-up of the voluptuously exhaled smoke that emerges from his mouth and nose. Plissken looks at the flame. Looks at the camera. And breathes out. And now it’s dark.

One might undertake the task of systematically noting and describing all the bubbles of light that, like the ones in Escape from L.A., hover for a moment between general darkness and final extinction. All these enclaves of time and space where the cinema, barely surviving itself, exceeding itself, or engulfing itself within itself, reserves the possibility of filming, in extremis, its apocalypse.

To mention only one further and very beautiful one, remember how, in Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), it all keeps rolling even though everything is empty and shut down on earth. It all keeps on rolling on board the submarine of Captain Dwight Towers (Gregory Peck), which is roaming the seas of a planet devastated by the Third World War. We do indeed get the impression that the two periscopes of the submersible traveling near San Francisco are cameras that are shooting a film of the deserted city from the ephemeral point of view of the survivors of the nuclear holocaust. Overwhelming images of a world no one inhabits any more, seen through the equipped eyes of those who are contained in this air pocket that, for a little while longer still, protects them.

In the epilogue, as mortal radiation draws close to Australia, the inhabitants of the last spared continent are now also getting ready to die. Captain Towers then decides to board ship with his men, who want to end their lives at home, in America. Staying alone on the shore, his girlfriend Moira Davidson (Ava Gardner) watches the submarine go underwater. The camera also dives down, the image goes blurry from all the bubbles and, thanks to a gripping fade-out, we go from the bubbling sea to a sheet of newspaper as it flies away, taken up by the wind in Melbourne’s depopulated streets.

All these bubble structures—the blob, the hologram, and the match, the submarine, but also the camera that falls to the ground and continues to film at the end of Cloverfield or (we are getting there) the “magic cave” of the last moments of Melancholia: We see and read them on two levels at once. On the one hand, they appear in one form or another within the continuity of the plot. And, on the other hand, they constitute fragile filmic enclaves within acinema, ephemeral shelters in the general explosion of the cineworld.

When these two levels intersect, is it then a matter of seeing the replay in an apocalyptic mode of what Jacques Rancière has described as a “thwarted fable”?7 Is it a matter of watching the spectacle of a cinema that, by narrating the end of the world, tries to grasp itself as the cinema that it is?

Cinema is, of course, constantly narrating itself and staging itself through the stories it tells. As Rancière also says, it is constantly “making a fable with another” and “making a film on the body of another” (5). And we have in effect explored the negative versions of these allegories or tautegories of cinema in cinema, those moments when the film seeks to abolish itself as if to get a better sense of its contours or its borders: the countdown, the freeze-frame, the cinepotlatch and pyrotechnics, the foliations of the flip-book, the archi-fade-out to black or white, x-rays, and heliographics, without forgetting the blob that covers the movie up with its emblobbing and self-consuming film.

But by narrating and auscultating itself from the perspective of its disappearance, cinema touches on a limit that is different from the one that would place the image and the fable in opposition within it. At stake is what we have called its cinefication: in other words the constitution of the cinema and of its signs propped up on or dependent on the ultimate reference of its cineration, its becoming ash. In other words: Cinema attempts to grasp itself not—or not only—by thwarting the stories it has to tell, but rather from the perspective of the end of film in general, in other words from the perspective of the radical finitude of the cineworld.

Yet this finitude is not that of a mundus that disappears in order to reveal (apokaluptein) a backworld or an other (cine) world [outre-cinémonde]. No such beyond exists. Taking up a famous and often misunderstood formulation by Derrida, we could say that there is nothing outside the film. There is nothing outside the film because the real to which we might want to oppose it already also has the structure of the cinema. This is in fact what the very concept of cineworld indicates: The world, “our world,” already counts the cinema “as one of its conditions of possibility.”8

In other words, the cinema is an “existential.” Or yet again, paraphrasing a certain Deckard, it’s because I am a film that I am.

Apocalypse-cinema, we were saying, is, each time unique, the end of the world and the end of the film, both the one and the other [l’une comme l’autre], the one in the guise of the other. Yet since neither the one nor the other unveils a revealed otherworld, they thus open the world onto itself by bringing bubbles, fractures, and fissures to emerge within it. Blobs and “cracks in the world,” in sum.

This is in fact why cinema is not Plato’s cave and acinema’s blinding heliography is not that of ideas, the copies of whose copies we would see on screen.9 And if the cineworld has the structure of a cave, it is much more that of the “magic cave” that Lars von Trier magnificently evokes in Melancholia.

What in effect is this magic cave that is constantly coming up in the film’s dialogue before it bursts as its last bubble? What is this bubbling katechon that holds the ending back, but just barely, that defers and suspends it, but hardly at all?

The cave is first mentioned in the first part of the diptych called “Justine,” which is devoted to the marriage of the eponymous character played by Kirsten Dunst. When her nephew, the little Leo (Cameron Spurr), starts to get sleepy during the party, Justine insists on putting him to bed herself. She cajoles him, makes sure he is comfortably settled in, while he asks her, “When are we going to build caves together?” They are going to build “lots of caves,” she answers, “just not tonight.”

At the beginning of the second section called “Claire” (which is the name of Justine’s sister, played by Charlotte Gainsbourg), the little Leo recalls the promise of his aunt, who has just got out of the cab: “When are we going to build those caves?” he asks her. But Justine, prostrate and plunged into a deep depression, remains mute. It’s Leo’s father, John (Kiefer Sutherland), who answers: “Not now, we’ll do it a little later on.”

While the construction of the cave is being deferred like this, the planet Melancholia is drawing closer to the Earth. John, who refuses to believe in a collision, is nonetheless gathering provisions just in case the star does really come very close. And in fact, Melancholia is becoming an obsessive presence in the sky, with its blue halo of a gaseous giant to which Justine, ever more invigorated, exposes her nude body for nocturnal light bathing.

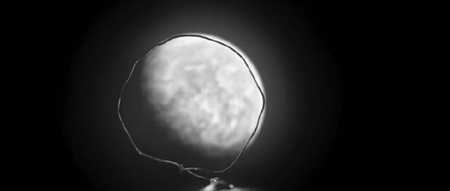

For want of caverns, the little Leo has in the meantime built an observation instrument: He has put together a kind of viewfinder made out of an iron wire twisted into a circle and hanging from the end of a stick so as to measure Melancholia’s approach with the naked eye. Without his yet knowing it, the child holds in his hands an apparatus for counting down the time that remains: By framing the threatening planet with this rudimentary, apprentice astronomer’s toy, he creates a visual enclave within the film’s field, where the cause of the coming end of the world is contained and enclosed. But the image in the hoop—that gigantic celestial sphere surrounded by a ridiculous skinny enclosure—will continue to grow, over-flowing this frame within the frame where it is encircled.

Lars von Trier, dir., Melancholia, 2011

In other words, the astral globe’s blob swells up and bloats like an on-screen tumor. And it will pursue its dilation until the final explosion. Until its luminescence, unfurling beyond every limit and every framing, produces a general fade to white followed by the darkness of the cineworld’s extinction.

John cannot bear the discovery that Melancholia continues to draw closer this way, unlike the optimistic predictions of science. Before the apocalypse, anticipating the end, he kills himself, and the two sisters are alone as they wait with little Leo. Justine is calm, while Claire panics. She tries to run away with her son, but to go where? There are electric arcs that rise toward the sky from the roadside poles. It is hailing.

While Claire sobs, Justine comforts little Leo. “I’m scared the planet is going to hit us anyway,” he mumbles in his aunt’s arms. “Dad says there’s nothing to be done, nowhere to hide.” And Justine answers him: “If your father said that, it’s because he forgot something. He forgot the magic cave.”

Here it is, then, the last bubble, more ridiculous and more moving than ever before. Because the famous “magic cave,” this insignificant katechon, so pathetic in the face of the approaching cosmic power, is more or less nothing: a handful of branches gathered in a rush in the surrounding woods, propped up against one another to make the cone of a tepee. Leo, Justine, and Claire are sitting in it holding hands.

And it’s a tepee without a canvas, without a wall.

This tent is so different from all the ones we usually see at the movies. To stay within the apocalyptic repertoire, I am thinking in particular of the one in The Road, a shelter that was thrown together with random pieces of fabric under whose roof, in the evening, the father reads a story to his son by the trembling light of a gas lamp. Seen from the outside, the tent looks like a veil where the silhouette of the man bent over the book and turning the pages is projected. In another genre, I am also thinking of The Lost World, the first sequel to Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg in 1997: Inside her tent, the paleontologist Sarah Harding (Julianne Moore), awakened by the thundering steps of a tyrannosaurus, sees the beast’s profile and jaw drawn in negative on the tent’s lining like a huge shadow puppet.

In short, whether filmed from one side or the other, from the inside or the outside, the tent’s canvas is generally staged as a screen that is reinscribed on screen.10 But in Melancholia, the tepee has no projection surface, as if it were the very apparatus of cinema that was dematerializing. Here, this magic cave, like the wire put together by Leo, is nothing other than the pure differential function of a frame that lasts long enough to make an image among the images, on the edge of acinema.

Lars von Trier, dir., Melancholia, 2011

Melancholia is so close now. Everything is bathing in its light, including the meager woody structure that stands out like a skeleton in the increasingly blinding whiteness.

“Close your eyes,” Justine tells Leo. And while the insistent sound of cellos rises from the depths of Wagner’s prelude, as the low noise of the coming star rumbles, they wait among the branches in this shelter that shelters nothing but the mere bubble form of a possible cineworld, suspended on the limit of its end.

Then the dazzling clarity comes.