‘I do not want my house to be walled in on all sides and my windows to be stuffed. I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.’

—Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

For some, flying to the Middle East for the first time, the standard two-year contract duration may seem like a long time to spend in what is generally portrayed as a tough assignment in a tough location. For others, the prospect of life in Saudi Arabia, with no income tax, few financial responsibilities, a house provided and lots of paid holidays, may lessen the perception of Saudi Arabia as a hardship posting. For most guest workers, the assignment works out. Many find, after their arrival, that the advertised hardships of Saudi Arabia have been greatly exaggerated—that Saudi Arabia is, in fact, an easy number. In actuality for some, particularly those with high status jobs, working in Saudi Arabia is a career highlight, with luxurious living and working conditions. But for the few whose assignment, for some reason, goes off the rails, Saudi Arabia can make life tough for its guest workers.

En route to Saudi Arabia, you will probably have formed some mental image of what lies ahead. Maybe friends, who have worked in Saudi Arabia, will have recounted many a lurid tale, suitably embellished to increase your anxieties. Your mind may be gripped with ill-defined fears, particularly if you are a woman. In women’s circles, this place has definitely acquired a reputation as a male-dominated society where women are afforded little respect and few privileges. To the guest worker visiting the kingdom for the first time, Saudi Arabia may be just a little bit scary. But the chances are, your fears will prove unfounded.

The only tourist visas issued into Saudi Arabia are for approved tour groups following organised itineraries and for Muslim pilgrims intending to discharge their hajj obligations. Other than that, unless they are diplomats, travellers to Saudi Arabia are workers or dependants of workers who must be sponsored by a company or a Saudi citizen living inside the country. Providing that passports are valid for at least six months, visitors will then be issued visas after presentation of the correct paperwork prepared by their employers. Family members are entitled to visit Saudi Arabia under similar arrangements. Their visa applications will also be processed by the sponsoring company. Visas are obtained through Saudi embassies or approved travel agents in the passport holder’s country of origin.

Getting a Visa

Precise information to be submitted to support a visa application may be obtained from the Saudi embassy website at http://www.saudiembassy.net/services/visa/default.aspx. Nine types of visa relating to employment or visiting rights are listed on the website. After an extensive paper trail detailed on this website, issuing time for visas is of the order of a week. For frequent business visitors from source countries that host an Arab or Saudi Arabian Chamber of Commerce, you can ask to be admitted to a VIP list so that your visa application will be fast tracked.

On departing the country, say for R&R or a business trip, workers and their families must obtain an exit permit arranged by their employer prior to leaving and an exit/ re-entry permit if they are returning to the kingdom after their sojourn away. Employees are not normally obliged to attend immigration offices either within or outside Saudi Arabia for this process. For those planning on travelling in and out of the kingdom on a regular basis, be it for business or pleasure, there is the option of applying for a visa that allows for multiple exits and re-entries within a period of about six months. The cost of processing this visa is about US$130 (SAR 500) per passport. Care must be taken to renew the visa before its expiry time, as the ‘six months’ period is calculated based on the Islamic, not the Gregorian, calendar. The visa is a one-page document that should be attached to the passport.

Two government websites offer speedy service in aiding the visa process for foreigners: www.eserve.com.sa (click “English” option) allows you to check the validity of your current visa, and www.gdp.gov.sa gives you the option of applying for a visa through the internet and mobile phones.

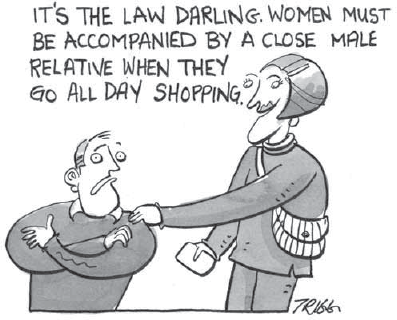

Visits to Saudi Arabia by women are subject to additional rules. To comply with local requirements that women be accompanied wherever they go in Saudi Arabia, sponsors must meet females of dependants on entry into the country otherwise they may be held at airports for long periods, possibly indefinitely. On the return journey, married women and children need their husband’s permission to leave the country.

The Paper Mill

Saudi Arabia has a large bureaucracy that has a commensurate appetite for paperwork. Once inside Saudi Arabia, you cannot be sure what documents will be needed, only that you’re likely to need plenty of them! Experienced Saudi hands assemble document packs, including many passport size photographs of each member of the family, photocopies of ID, copies of most other important documents in your CV—birth certificate, marriage certificate, ‘no objection’ letters and employment contracts—health cards, certificates of academic qualifications preferably all attested to by your country’s own embassy in Saudi Arabia.

Under Saudi law, it is no longer required for the employer to hold its employees’ passports while employees are in the kingdom. However, many companies have not yet complied with this rule and continue to hold their foreign employees’ passports. This can have a real downside if you are unfortunate enough to work for an unscrupulous employer. Without a passport, in the event of a dispute between employer and employee, there is no way for a disgruntled employee to get out of the country, unless they happen to hold double citizenship, in which case they have access to another passport. Situations in which the employee is completely at the mercy of the employer have led to occasional sad stories of employee abuse.

No one who has an Israeli visa stamp in their passport can get a visa for Saudi Arabia. Anyone who wants to visit both Israel and Saudi Arabia needs to get two passports, or make an arrangement with the Israelis for a removable visa. An extreme case of anti-Jewish sentiment in the authors’ experience was the censoring, by an over zealous censor, of the word ‘juice’ from cans of fruit juice in the local commissary. Presumably this word was too close, phonetically, to the collective noun for the Jewish race. On each can, this word was blacked out by the Saudi censor’s ubiquitous accessory—the black marker pen.

In a parallel story, a past Australian ambassador to Saudi Arabia related the story of an Australian businessman who did a little jail time on his first visit to the country after a misunderstanding with an immigration official. The Australian businessman, it seems, had a slight speech impediment. When the immigration official asked what was the businessman’s country of origin, he evidently thought he heard the reply ‘Israel’ instead of ‘Australia’. Handcuffs were duly installed and the offender was whisked off to jail without so much as an opportunity provided for the offender to present his passport.

Expats travelling to Saudi Arabia to work will also need their employer’s help in getting an “Iqama”—an ID card, which is carried on the person verifying that the holder has legal right to be in Saudi Arabia. Since most employers still hold the guest worker’s passport, the Iqama is the principal ID document a guest worker must keep on their person while in Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, when a guest worker leaves the country, the Iqama is exchanged for the passport and given back to the worker only upon his return to the kingdom.

Without an Iqama, you will be unable to open a bank account, lease or buy a car, lease rental accommodation or transact other normal day-to-day activities. You may also be harassed in the event of police checks. In theory, your employer should be taking the initiative in organising the Iqama. However since the penalties for failure to produce an Iqama on request lie with the employee, it pays guest workers to ensure that the Iqama is a) issued, and b) re-issued before 45 days from date of expiry.

The climate of Saudi Arabia, being hot and dry, is intrinsically bug-resistant. No injections are stipulated by the government as a condition for entry. Some visitors obtain a meningitis vaccination. Hepatitis A shots are recommended by many doctors. Those visiting the coastal plains of south-west Saudi Arabia—well away from most normal tour of duty areas—might be advised to take anti-malaria precautions. Those travelling near Mecca in the pilgrim season may consider taking precautions against Meningicoccal disease or meningitis that may be brought into the country by pilgrims from tropical Muslim countries.

Saudi Arabia spends about 5 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care—about one-third the rate of the United States and half that of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. Medical care is provided to Saudi citizens free of charge. Western health care workers report that Saudis tend to be on the opposite end of the health care scale to hypochondriacs. Saudis don’t visit doctors unless they feel seriously unwell, thus reducing the strain on the health care system. Given the strength of their religious beliefs, Saudis probably aren’t quite as obsessed as the typical Westerner with an ambition to prolong life as long as possible. The average lifespan of men is a modest 72 years and of women, 76 years.

Health care in Saudi Arabia is a curious mixture of rudimentary primary medical care and a few lavishly equipped Western-style hospitals. The healthcare system is largely staffed by expatriates.

Guest workers may or may not have to pay for health costs depending on their employment conditions. Many large projects employ their own doctors, with health care included in employment packages. Despite the high standard of their hospitals, primary medical care is still fairly basic. If health care is not provided in the employment package, selection of one’s health care provider is important. From an expatriate point of view, some excellent hospitals are available—along with some that are not so good.

As a guest worker in the country, how you live will depend on who you are, what you have come to do and the organisation you are working for. If you are a Western businessperson heading a major corporation, you will enjoy the same luxury appointments in Saudi Arabia that you have come to expect wherever you travel. If you are working for a branch of a large company, you will probably be given comfortable accommodation, not quite up to luxury class. If you have come to work for a Saudi company, the likely standard of your accommodation is harder to predict. Large Saudi companies house their employees in all standards of accommodation, from the opulent to the very ordinary. At the other end of the employment scale, if you are an Indian houseboy in a luxury house, you would normally have a small room, though accommodation in stairwells, cupboards and shipping containers in the back garden have also been reported. Four or five labourers from Pakistan and Yemen might typically share a room someplace and sleep on the floor.

As a Western expat worker, the most common style of accommodation in Saudi Arabia is the ‘compound’, which is essentially an expatriate enclave kept fairly separate from the Saudi Arabian mainstream community. The model for this society evolved in the first days of Saudi Arabia’s now well-established imported labour programme. Aramco was established in 1948 to develop Saudi Arabia’s first major oil strike at a favourable geological formation called the Dhahran Dome near the eastern seaboard. The area was arid and featureless. One small trading post, the now bustling town of Al Khobar, nestled nearby on the shores of the Persian Gulf. The nearest inland settlement was an oasis at Hofuf, about 150 km (90 miles) to the south. The site of the future oil wells and extraction facilities was a wide expanse of empty land. Readymade accommodation for Western visitors was non-existent.

To develop this great new oilfield, specialist expatriate workers to the Middle East, mainly US citizens, were imported to drill the wells, lay pipelines and build facilities needed to pump the oil into tankers pulling into Persian Gulf ports. To meet the need of this imported workforce for Western-style accommodation, the oil company created a typical American suburb amongst the wastes of the Dhahran desert, importing everything they required from kit homes to the grass for their sidewalks. They set up shopping facilities, banking, schools, hospitals, sports facilities and a radio station. The suburb, somewhat unimaginatively christened ‘The Aramco Compound’, was built and peopled by Americans who acted American, spoke American and might have been living in downtown Burbank.

As the nation’s oil revenues rolled in and were expended on development projects, replicas of this kit-form city were built elsewhere. At various large projects around the country, a number of Western-style towns have been constructed, initially inhabited by construction personnel, and later by Saudis. If you have come to Saudi Arabia to work on a construction site or to work in an existing industrial city, you have an excellent chance of living in a ‘compound’ that resembles the suburb of a dusty desert town, perhaps with neat streets, gardens and lawns irrigated by desalinated seawater. With increased security concerns in recent times, some compounds are now fortified settlements and are surrounded by walls and a cleared security area with high razor-wire fences patrolled by the Saudi Military. Residents of compounds tend to conduct most of their activities inside the compound’s boundaries. Likewise most Saudis tend to stay outside. Within the compound, you can probably live a similar life in Saudi Arabia to the one you left in your country of origin.

The standard of accommodation offered in compounds could be a single room ‘dog-box’, a trailer home imported fully assembled or a luxury permanent home in an established suburb. Suburbs and compounds of large cities are generally well-equipped with sporting facilities, community centres, movie theatres and shops. Some visitors may feel right at home in these facilities. Others may find that living in the company-provided accommodation of Saudi Arabia is superior to anything they have experienced back home in their countries of origin. A few might feel that compound life is artificial and yearn to pitch a tent in the desert.

If you are working in a city, instead of a compound you may live in an apartment or perhaps in a hotel. Apartments and hotels in Saudi Arabia are much the same as Westernstyle apartments and hotels anywhere else. This is no rundown country where you have to visit the well to pump water. Saudi Arabia has a developed infrastructure. Almost everywhere you will find the full suite of services—electricity, running water, sewerage and motor car access.

Those not living in company-supplied accommodation can consult estate agents dealing with rental property. Rental leases can run either for an indefinite period or a specified period. Short-term and long-term leases are available. Rental accommodation is customarily provided with basic furnishings. The cost of rental accommodation, if required, varies greatly with location. The most expensive real estate in Saudi Arabia is in Mecca during the pilgrim season. As an expat, you are unlikely to live in Mecca unless you work for a large building contracting company with a contract to construct a high-rise building to service Mecca’s construction boom. Jeddah, Riyadh and Al Khobar are more likely destinations. A website for those who wish to enquire about rental apartments and homes is:

http://www.saudiarabia.alloexpat.com/ real_estate_ saudi_arabia/agent_developers

You may also wish to contact them for more information at email: info@asinah.org.

By the standards of Asia, large cities in Saudi Arabia are reasonably user-friendly for the handicapped. Good hotels and public buildings tend to have reasonable access to ramps. But conditions of streets and sidewalks (if any exist) may be hazardous for the handicapped, particularly in the smaller towns.

The monetary unit of Saudi Arabia is the Saudi Riyal (SAR), which since May 2008 has been pegged to the US dollar at the rate of SAR 3.76 to the dollar. The highest denomination note is SAR 500 and the smallest SAR 1. Other notes of various denominations are in circulation down to the smallest value note of one riyal. The minor unit is the halalah which, at 100 to the riyal, is of nuisance value only.

Changing travellers cheques is generally more difficult in Saudi Arabia than most places. Many banks and money changers simply won’t accept travellers cheques. Others will exchange only the particular issue of travellers cheques they deal in themselves. Also, unlike most places, you will need to present your original purchase receipt when cashing your travellers cheques.

US dollar bank notes, everyone’s favourite currency, are easy to exchange. Whatever you are changing, you are likely to get a better rate of exchange from money changers than from banks.

Cash withdrawn at the local Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) linked to a home-based bank account is probably the easiest way to generate cash in the kingdom. Two advantages of ATMs, apart from convenience, is that they don’t discriminate against females or close down for prayer calls. Credit cards are also widely accepted. Whatever method you select to meet your day-to-day expenses, people working in Saudi Arabia, living in free company housing, sending their kids to free school generally enjoy a highly subsidised lifestyle and don’t need much more than petty cash when in Saudi Arabia.

Except for restrictions on females, guest workers can open accounts with Saudi banks. But generally there is no need to do so. One of the authors did open a cheque account with a local bank while in Saudi Arabia, and closed it shortly afterwards. The hassles of operating the bank account were hardly worth the effort for little advantage. Most expatriate workers get their pay cheques credited directly into the banks in their own countries or elsewhere. There are no restrictions about sending currency out of Saudi Arabia. If you do want to enquire about Saudi banks, there are many available that may or may not have links to your offshore bank.

The Saudi Arabian banking system isn’t comfortable with some of the ethics of modern commerce. The Qur’an contains provisions precluding money usury, which is alternatively defined as ‘interest’ or ‘exorbitant interest’. Whether exorbitant or not, Wahhabis aren’t keen on the notion of interest at all. By the same token, the realities of the commercial world are recognised. Since interest is the keystone of the banking system, this ideological difficulty has rather limited the opportunities for Saudi banks.

To overcome the problem, Saudi Arabia, in line with other Middle East countries, has two banking systems—Islamic and Western. Islamic banking invests only in companies that provide acceptable goods and services, develop Islamic products and conform to Shariah Law. Companies that provide social welfare services are favoured. Companies that deal in tobacco and alcohol are precluded. Some major international banks such as Cititbank and Hongkong Shanghai Banking Corporation have Islamic banking divisions operating in Saudi Arabia.

Traditionally Saudi Arabia has worked siesta hours. Commercial hours for retailing are customarily from 8:00 am–1:00 pm, then 4:00 pm–8:00 pm (some variations may occur). Government offices may skip the afternoon shift and may only be open from 7:00 am–1:00 pm. Some may stay open till 2:30 pm. These trading hours were established to suit the rigorous climate of the country. With the advent of air-conditioning, the climate is less relevant than it once was—at least inside the offices and malls. Many offices now work more normal business hours—9:00 am–5:00 pm, or something similar. These hours apply most of the year except Ramadan, when retail businesses are extensively shut during daylight hours, but are normally open in the evening.

Since Friday is the religious day, the working week is from Saturday to Wednesday. Weekends are on Thursday and Friday. Businesses and government offices are normally closed and most shops are normally opened during weekend trading hours.

As well as their regular opening and closing times, shops will also close three or four times a day for prayers. The practice of closing down for prayers can seem remarkably inconvenient to the Western shopper. Experienced shoppers time their shopping expeditions to fit in with prayer timetables. The most efficient shopping expedition is one in which prayer time is spent travelling either to or from shops. Prayer times vary according to a sliding scale depending on the times for dawn, dusk and the phases of the moon. Lists of prayer times obtainable from places like bookstores are worth getting as an aid to scheduling appointments and shopping expeditions. Prayer times are also provided in daily newspapers.

Electricity supply is reliable and power cuts are uncommon. Electric power is supplied principally at North American voltage and frequency—110 volts and 60 Hertz. But in many offices and hotels and some residential homes, a 220v/50Hz outlet is available. Voltage regulators are recommended to protect appliances from supply fluctuations. Sockets and plugs are not standardised and vary between the British, US and European types. Those travelling in Saudi Arabia are advised to take a transformer to obtain the correct voltage for their appliances, and to carry a plentiful supply of adaptors to fit the various plug types.

Saudis of quite modest means engage domestic servants from Sourtheast Asian and sub-continent countries. Guest workers in upper socio-economic groups may wish to do the same. Unless it is provided in the employment package, expatriates who wish to employ domestic help will probably enter into an informal arrangement with someone already in the kingdom working for someone else. Plenty of Third World Country employees are on the lookout for moonlighting jobs to supplement their incomes. More permanent arrangements are unlikely to be convenient since the visas for domestic employees bind employees to specific employers and no one else. Saudi Arabia expects its guest workforce to visit the kingdom for the specific purpose of undertaking an employment contract for a specific employer for a specific contract period at the end of which they are expected to leave.

Visitors with a valid driver’s licence from most countries, or an international driver’s licenses, are allowed to drive in the kingdom for up to three months. After that, foreign licenses can be converted to Saudi licenses without undergoing a local driving test—but with the usual small mountain of paperwork required in Saudi Arabia for such transactions, including a translation of the licence into Arabic, a letter from your employer, an application form, and a copy of your Iqama.

Good quality highways connect major cities. Travelling long distances in quick time is comfortable provided your car has a good air-conditioner. Petrol is cheap. Inside towns and cities, the customary traffic snarls may sometimes occur as they do anywhere. But between cities, traffic flows freely. Compared to most countries, the traffic on roads is light. In 2005, the rate of car ownership was about 420 cars per head of population—similar to western countries. A point to be noted is that over half the indigenous adult population —Saudi women—are not permitted to drive. But that hasn’t prevented Saudi women from owning cars. According to figures supplied by Aramco, 75,522 women owned 120,334 vehicles by the end of 2006—all, so far as is known, driven by male chauffeurs.

That’s the good news about driving. The bad news is that the nation’s highways and byways are downright dangerous places to be. Those who hold that the female of the species is the more dangerous one on the roads than the male will find little support for their case from the road accident statistics of Saudi Arabia. That Saudi roads are perilous places is evident merely by driving through the countryside. The nation’s highways are littered with wrecked cars that are merely dragged to the side of the road and abandoned as a silent testimony to the hazards of driving on the nation’s roads.

The Perils of Motoring

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), Saudi Arabia has the world’s highest number of deaths from road accidents. From 2008 to 2009, the kingdom saw a total number of 485,000 traffic accidents, which resulted in 6,485 deaths. Saudi Arabia fared even worse in comparison when this was measured in fatalities per vehicle. Saudi Arabia has road accidents at about three times the rate of Western countries like the USA and Britain. Various studies have also been conducted to determine the cause of Saudi Arabia’s high accident rate. According to one of many reports on the subject—an epidemiology of road traffic accidents in the Al-Ahssaa Governorate: ‘Very high speed was responsible for about 70 per cent of accidents’. (Alcohol can certainly be ruled out as a principal cause of accidents.)

Driving standards in Saudi Arabia are on a par with the worst anywhere. In the opinion of the authors and absolutely unsupported by any research that we know of, there is one particular element of Arab culture that seems to us to make driving hazardous. Science has shown that about 40 per cent of the evaporative losses from a human body labouring under a hot sun are through the top of the head. Arabs developed the appropriate headgear to deal with this problem. For camel driving across the sunny deserts of Saudi Arabia, the gutra is no doubt ideally suited to the job of providing shade and preserving bodily fluids. But this item of national apparel is not equally suited to all forms of locomotion. One aspect of gutra-wearing renders it particularly unsuited for driving cars. The fall of the material on both sides of the face obscures peripheral vision. Saudi drivers seem particularly bad at seeing other cars coming at them from the side.

In addition, a popular view among expats is that Saudi drivers bring to the roads their carefree fatalistic attitude that events on the road, and in life in general, are in the hands of a higher authority than themselves. This being the case, they might argue, what difference does it make to speed around blind corners and over crests on the wrong side of the road? What is going to happen is going to happen.

Whatever the cause of their bad driving, Saudi Arabia is a country where you should, above all things, drive defensively. When you are at the wheel, assume that the nation’s roads are likely to be peopled by semi-blind maniacs travelling towards you at high speed and not necessarily on their side of the road. Never suppose that people will stop at intersections or stop at red lights. In cities, always expect that cars may pop out in front of you from streetside parking spots. And remember that whatever the circumstances of an accident, under Shariah Law, if you hit a car driven by a Saudi, you will most likely be blamed, however blameless you consider yourself to be.

Assuming you are tolerant of religion, not mounting a crusade to topple the government and refraining from selling alcoholic drinks to the local population, the most common legal problem you are likely to encounter in Saudi Arabia is a road accident. That said, many expats do drive in Saudi Arabia and emerge from the experience unscathed. But if an accident occurs and you are involved, the Saudi authorities will dispense blame for the accident in a fairly ad hoc manner across whoever happens to be at the scene of the crime. Rough justice can be administered, with the risk that the innocent may be enmeshed in the outcome along with the guilty.

Underlying Saudi law is the concept of qisas, or retribution. Under this code, when a crime occurs, a similar level of suffering is meant to be inflicted on the perpetrator of the crime as has been inflicted on the victim. Saudi law may take the Biblical maxim of ‘an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth’ quite literally. For example, in 2000, an Egyptian expatriate worker had his eye surgically removed after he threw acid in the face of another man, causing his victim to lose an eye.

As an alternative or an addition to punishment, the Shariah Law of diya also allows the concept of blood money. As well as being punished by the state, the perpetrator of a road accident is expected to compensate the victim, or if the victim has been killed in the accident, the victim’s family. Saudi courts will prescribe the payment of blood money based not so much on the injuries inflicted but on the status of the victim and the ability of the perpetrator to pay. (The West, which has a very poor record for compensating victims of crime, might take note of this!)

Getting Third Party Insurance

(And Staying Out of Jail)

Blame for road accidents may be apportioned to innocent victims of road accidents on the grounds that if they hadn’t been at the scene of the accident, nothing would have happened. Expats can expect to fare worse in these situations than Saudis for whom a lesser burden for proof of innocence is required.

Any expat driving in Saudi Arabia must ensure they have comprehensive insurance cover, and should carry a full set of insurance and personal travel documents whenever they undertake a journey on Saudi roads. In recent years, compulsory third-party insurance has been introduced in line with what is practised in most countries. Since 2002, both resident and non-resident drivers in transit are required to apply for rukhsa— equivalent to third-party insurance in other countries—to protect drivers against personal injury claims from other drivers. Rukhsa insurance covers third party rights to diya—or blood money claims for relatives of road victims. A statement from Allied Company for Co-operative Insurance and Reinsurance provided these words by way of explaining the principle of rukhsa:

‘Rukhsa covers the blood money of a person killed. In the absence of this cover, the erring driver would remain in police custody until the blood money, a bond or a guarantee from his sponsor, was furnished.’

There are a couple of common sense rules about road accidents. In the first place, if this is someone else’s road accident—stay out of it. Saudi Arabia is not the place to discharge the role of good and dutiful citizen. If you come across a road accident, and feel a compulsion to become involved, bear in mind that when the authorities arrive, the first thing they are likely to do is throw a cordon around the scene of the crime. Anyone inside the cordon will be considered involved. The damaged cars will be dragged to the side of the road, where they may stay for a very long time and perpetrators, victims and bystanders at the scene of the accident are all likely to be taken away by the authorities for processing. Justice can operate very rapidly and inaccurately. Or the enquiry may be prolonged. Perfectly innocent bystanders might have to spend weeks in jail while enquiries are conducted regarding their degree of involvement. Once released, if the case is not concluded, witnesses might have to stay in the kingdom for months, denied exit permits while cases drag on. Only those with a hyper-acute sense of public duty are going to get involved in someone else’s road accident in this country.

If this is your own accident, things are decidedly trickier. It is easy enough to state that you should avoid an accident. But the nature of accidents is that they happen. One of the risks of driving in Saudi Arabia is to be involved in an accident in which, in your own country, you would have been considered entirely blameless. Various judges have enunciated to guest worker defendants of traffic charges the principle of Saudi law on this matter—the accident must be your fault, since if you had not been there, the accident would not have happened. One of the authors has personal experience witnessing an accident at an intersection where the Saudi driver went through a red light and collided with a car—driven by an expat—executing a left-hand turn. The expat was held guilty on the grounds that the light showing on the street he was turning into was red at the time of the accident. Besides, if he hadn’t been there, he wouldn’t have been hit. That sort of logic is hard to beat in court.

As a last word on this subject, if you do happen to end up in jail for some reason, make sure someone knows you are there. Saudi Arabia is a free enterprise economy. Jails in Saudi Arabia provide only the minimum of accommodation services. Luxury items like food, water and toilet paper are meant to be provided by friends or family of the detained.

There are two types of taxis in Saudi Arabia—coded by colour—white taxis (limousines) and yellow taxis (ordinary taxis). In most cases, limousines, which also co-ordinate with hotels, are to be preferred should the choice be available. Fares are generally reasonable. As an additional caution, unaccompanied women are advised against taking a yellow taxi due to the problems that might ensue from being caught by the religious police with a strange man in an enclosed space.

The habits of Saudi taxi drivers are similar to the habits of taxi drivers worldwide. They drive fast and they have a reputation, whether earned or not, for sharp practice. The standard of taxi-driving in Saudi Arabia is probably no better or no worse than anywhere else. In a country where the accident rate is amongst the highest in the world, you are probably safer in a taxi than with most Saudi drivers.

In taking a taxi, as in all aspects of life in Saudi Arabia, religion may influence the experience. Taxi drivers are theoretically supposed to stop whatever they are doing when prayer time is announced. (Airline pilots seem to be exempt from this requirement.) In practice, many taxi drivers may pull over during the journey and conduct their prayers at the side of a road or even in a mosque. The polite thing for you to do in this situation is to wait. Another option, if you are a man, is to catch a bus, should you be able to find one heading in your intended direction. Clerics appear to have granted bus drivers a general exemption from the obligation to pray—at least while in the act of driving the bus.

That Saudi Arabian towns generally lack street names and house numbers has restricted the Saudi Arabian postal delivery to sending mail to private mail boxes of which the country has about 700,000. Normal practice is to use a post office box number. In recent times, Saudi Post has embarked on a programme to overcome the country’s absence of a street addressing system. Initially, streets will be coded by number. Ultimately, assisted by GPS technology, each individual building will be recorded on a database using a 13-digit code, which becomes the address of the building. If successful, this will enable person-to-person mail delivery, as practiced in other countries. This programme started in Riyadh in 2006 and is expanding into other cities.

The Saudi Arabian Ministry of Information extensively scrutinises media entering the country for religious purity and political correctness. Detailed interpretation of the Qur’an during the 1970s determined that screening a film for public viewing in a cinema was against the rules, but broadcasting the same films into people’s homes on TV was permissible. In reaching this ruling, the Saudis may have objected less to the content of the films than to the cinema itself. Neither the clerics nor the authorities liked the idea of a crowd of strangers gathering in a dark place where conspiracies could be hatched, lewd acts could be performed and bombs could be exploded. This rule was cautiously relaxed in 2005. The cinema is located at Riyadh Hotel and showed foreign cartoons dubbed in Arabic. The audience was excluively women and children and sidestepped religious demands for gender segregation. In 2009, Menahi, a comedy starring Saudi actors and produced by a Saudi media company, was screened in Riyadh’s King Fahd Cultural Centre. Although only men and children were allowed to enter the centre, some religious conservatives gathered outside the centre to try to discourage people from watching the film.

Though cinemas are restricted, popular Westerns and other films are screened on TV. Government censors hack and slash content at will. Politically offensive material, such as content interpreted as pro-Israel or anti-Muslim, may be taken out. Large gaps in films when the screen goes blank (as distinct from cutting and splicing) may appear without notice, indicating that material showing physical contact between male and female has been removed. Since the dialogue also goes missing in the sequences, this can render the story line hard to follow.

If you are curious to find out what Saudi television is about and you are a non-Arabic speaker, Channel 2 broadcasts exclusively in English, except for a French-language newscast every night at 8:00 pm. Those in the Eastern Province can also receive Aramco’s TV station, Channel 3. It tends to be more up-to-date than Channel 2 and provides a film service in English.

The level of censorship can be quite informal and unpredictable and can be subject to decisions at the highest level. In one incident, at 10:00 pm one night, King Fahd telephoned the Saudi Minister of Information, Mr Ali Al Shaer, to complain about an Indian film that was being screened. The call came through on a party line and was heard by a Lebanese newspaper editor, who reported it to the wider community. “I don’t care if you are halfway through the film,” the King is alleged to have said, “stop it and put on an American film instead.”

State-owned and censored Saudi TV has come under intense competition in recent times from TV broadcasts by more liberal neighbours. Arab TV newscasting really made a hit with the world during the second Gulf War. Likewise, Al Jazeera, the Qatar-based news channel, presented a much more balanced view of the war than the likes of CNN. Al Jazeera had more correspondents on the ground in Iraq during the conflict and presented a ground-based view of the fighting. During this time, Al Jazeera claimed 35 million viewers and its reports made from within Iraq were carried by TV stations around the world. (According to documents subsequently released, George W. Bush proposed to bomb Al Jazeera in Qatar for presenting what he considered an ‘anti-American’ view of his war in Iraq. Allegedly, he was talked out of taking this action by British Prime Minister Tony Blair.)

A new station, Dubai-based Al-Arabiya, is broadcast on Jordan and Saudi state-owned TV and reaches a potential audience of 13 million, in addition to its satellite audience. Abu Dhabi TV is also well established and is second to Al Jazeera in popularity. Satellite TV is now widely available, allowing guest workers to stay in touch with developments back home and elsewhere. Theoretically, satellite TV is illegal in Saudi Arabia. The profusion of satellite dishes on roof tops and the walls of buildings bears testament that this provision is not widely enforced.

Like most of the developed world, watching TV is a favourite pastime. To maintain cultural, political and religious purity, every television set sold in Saudi Arabia has an encoded blocker which blocks incoming satellite TV signals. The highest TV viewing period is during Ramadan, when Arab TV stations launch their new programmes. This is also the busiest period for TV technicians hired by television set owners to unblock the blockers so that viewers can access racy Egyptian and Lebanese dramas the censors would prefer them not to watch.

In addition to TV, various radio stations broadcast a wide content in various languages. Radio AFRD, the US military station, The Voice of the Desert—in 1950 one of the first radio stations in the world to broadcast in FM—pioneered the idea of completely ignoring the culture of the host nation. To sooth its troops, AFRD played only a format of Western music. Radio Aramco, specialising in American country and western music like a broadcaster in backwoods Virginia, did likewise. These days, Saudi Arabia has 43 AM and 31 FM, as well as two short-wave radio stations.

Shopping is a major social activity for Saudis, particularly women, who otherwise tend to be housebound. Shopping in Saudi Arabia can be like shopping anywhere, or it can have its own distinctive flavour. Like the rest of the world, Saudi Arabia offers a choice of shopping malls, shopping plazas with Western-style supermarkets filled with familiar brand names.

In Jeddah, the Jamjoom Commercial Centre, just off the corniche, is a distinctive blue glass and chrome complex. In Riyadh, there is a profusion of swanky shopping centres, such as Kingdom Mall, Centria and Riyadh Gallery, among many others. All of these carry high fashion brands as well as a wide range of European and American merchandise. Shopping centre prices are mostly fixed, though a spot of bargaining can sometimes yield results. Merchandise on sale is not quite unlimited. The normal Saudi standards of modesty apply in malls as elsewhere. Shops in the kingdom do not stock the chic merchandise that can be seen in the neighbouring countries like the UAE or Qatar.

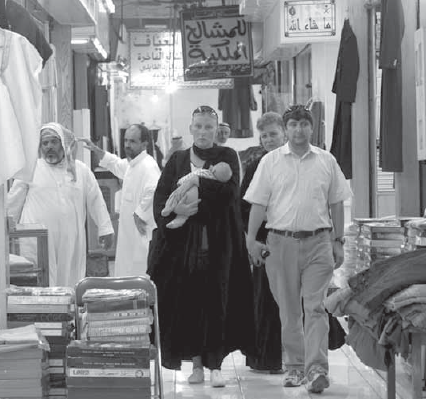

The country has also retained its souqs—markets of street stalls found in every large town where gold, fabrics, wall hangings, jewellery, brass coffee pots and bric-a-brac are on sale, and the aroma of incense and spices hangs in the air. Gold in the form of coins, small bullion bars, jewellery and ornaments is widely traded in the country.

An expatriate man accompanies his wife and mother as they go shopping in the souq.

Riyadh’s camel market is one of the largest in the world and is said to sell about 100 camels every day.

At the souq, the price of almost anything is negotiable to a point known only to the vendor. If you have the patience, you can haggle down to rock bottom prices, but the process takes time and can be hard work under the pitiless Arabian sun. Serious bargaining requires certain rituals to be conducted, including walking out on your vendor’s ‘last price’ at least a couple of times.

Feminine hygiene products do not sell well in supermarkets. Saudi women are likely to be too embarrassed to take such items to the (male) checkout ‘chick’. Instead, Saudi women source their personal hygiene needs at the souqs specialising in these products and staffed by other women. In the Kingdom Shopping Centre in Riyadh, an exclusive floor into which men may not venture is provided for ‘Ladies Only’.

If you happen to be in the market to buy a camel, the world’s largest (and allegedly smelliest) camel market is situated on the outskirts of Riyadh, about 30 km (18.6 miles) from the city centre.