‘Travel expands the behind.’

—Sir David Frost, BBC commentator, Surviving the Climate

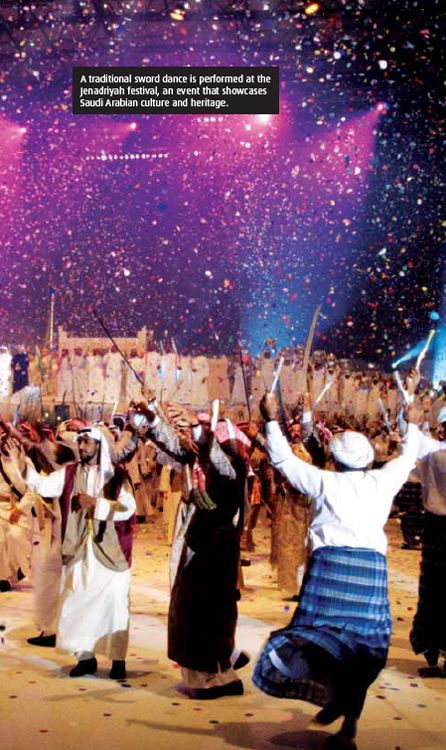

To a potential visitor, the image of Saudi Arabia is a country of endless desert and blistering heat. Perhaps this is an exaggeration. The daytime temperature over most of the country is ferocious in summer and most of the country is desert. But from about November to February, the weather in the area is quite pleasant. In fact, in parts of the country, nights and early mornings can even become quite cold. Inland, in winter, the minimum temperature can drop below 0°C.

Come Spend Your Next Holiday in Saudi Arabia

An imaginary tourist brochure might advertise the charms of the Persian Gulf and Red Sea settlements in words such as these:

‘... spend winter in the country where the sun shines all day long. You can book a pleasant room in a seaside hotel, take a stroll along the esplanade in the warm winter sunshine, and breathe in the exciting flavours of the east. The sea is warm, calm, clear and inviting. The beaches are sandy. The temperature outside is just right. The fresh northern breezes blowing down the Gulf cool your skin. Shopping in the souqs of the crowded marketplace is exotic and tantalising. Gold is cheap. Myrrh and frankincense are available in gallon jars. You can buy shimmering fabrics, elaborate coffee pots and the most fantastic range of jewellery. Down the road, the minarets glint in the early morning sunshine. Out on the peaceful waters of the Arabian Gulf, you can take a trip on an authentic Arabian dhow, just the way it was when these ships used to sail to the East to return with the fabled products of the Indies...

What a place for a holiday!’

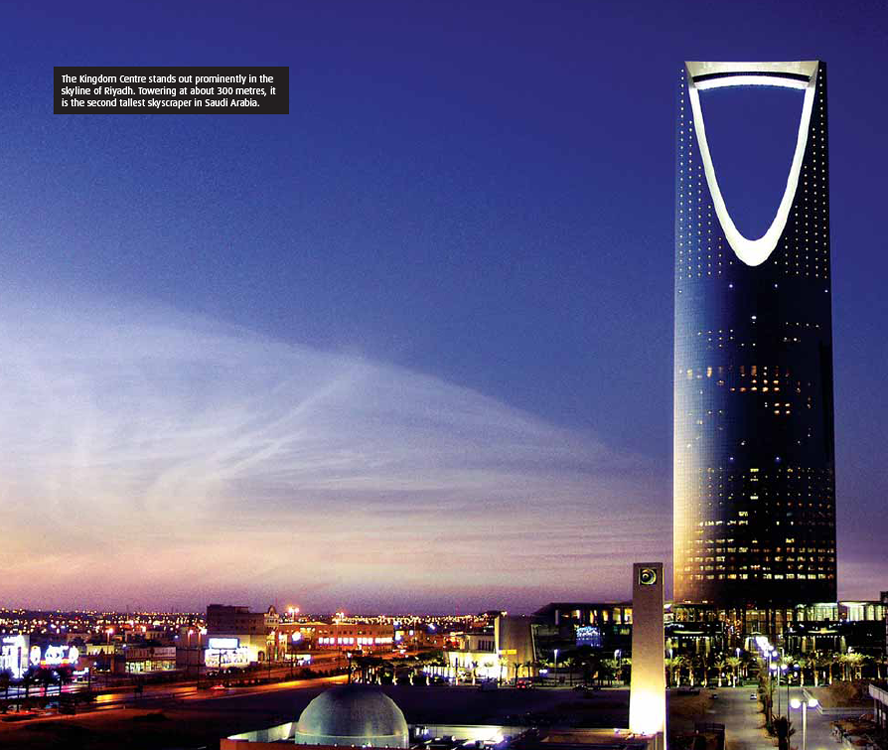

It has to be said, few tourists are tempted by this splendid vista of mild winter weather and sparkling blue waters for the very good reason that visas are not offered to tourists except under most exceptional circumstances. Other than for pilgrims and the most intrepid adventurers, Saudi Arabia has yet to make a significant impact on the tourist map. But for guest workers, the pleasant winter conditions are there to be enjoyed, hot summer weather notwithstanding.

While the country is generally arid, it does rain occasionally. Riyadh, the capital, averages 81 mm (about 3 inches) annual rainfall. Jeddah, on the Red Sea coast averages 50 mm (about 2 inches). What rain there is falls as brief winter downpours that disappear rapidly into the thirsty sands which, a few days later, may display a tinge of green. Life in the desert is nothing if not tenacious.

In paved areas, storm drainage systems range from inadequate to non-existent. Many buildings have been built below street level. For a day or so, passing clouds that stray from their normal flight paths can turn arid Arabian towns into quagmires. After a cloudburst, traders patiently bail out their stores and wait for normal weather conditions to return. So before setting off for Saudi Arabia, don’t forget to pack your umbrella! This item is not readily available within the kingdom for the few days when it is needed.

For visitors from more temperate climes, the sight of rain may be a reminder of an event they never thought they’d miss. The noonday sun is not the only climatic phenomenon into which mad dogs and Englishmen venture. English expats working in Saudi Arabia to escape from the weather back home have been known to immerse themselves into these brief and occasional storms, to perform a dance of gratitude to the rain god.

The other distinctive climate feature in Saudi Arabia is wind. The prevailing wind, the north-westerly shammal, rises in the mountains of Turkey and blows down the axis of the Arabian Peninsula. A less frequent wind, the qaw, sometimes blows with equal force from the opposite direction. When winds blowing across deserts reach a certain strength, they start to pick up sand. Shammal has become Saudi Arabia’s generic term for a full on sandstorm, from whichever direction it blows.

Walking around in a shammal in daylight hours is an eerie experience. Your world is suddenly reduced to monochromatic orange. No features are visible. The sun is blotted out and complete disorientation is but a step away but for one thing—you can navigate by the direction of the wind. Shammals can last for periods ranging from a few hours to days. Millions of tonnes of desert migrate this way and that in a swirling sand curtain that may extend one hundred feet into the air. Sand settles everywhere and anywhere. It gets into your house through the smallest crack. Possessions inside and outside buildings get covered with a fine grit. If the winds are high, painted objects like cars may be sandblasted back to bare metal. In coping with shammals, the ancient rule of the Bedouins still applies: during a shammal, rug up and stay inside.

At certain times of the year, figuring out the date may be a little more difficult in Saudi Arabia than in other places. The basic units of time—the second, the hour, the day and the seven-day week—originated thousands of years ago by the early Sumerians, are the same in the kingdom as they are elsewhere. To measure the span of its years, Saudi Arabia has adopted the Islamic lunar calendar with a starting date in AD 622, the year the Prophet Muhammad fled Mecca for Medina, an event known as the Hejira. Islamic years are denoted as ‘AH’ or Anno Hejira, just as ‘AD’ means ‘Anno Domino’, the Latin phrase meaning years since the birth of Christ.

Based on the lunar cycle of the moon’s orbit of 29.53 days, the Islamic calendar alternates 29- and 30-day months. The Islamic year has 354.36 days—the time taken by the moon to make 12 earthly revolutions. The fractional day is accommodated with a leap year of 355 days at three-year intervals to synchronise the orbital period of the moon with the rotational period of the earth. Further, finer adjustments to align the third and fourth decimal points of the lunar and solar orbits are made at longer periods. This is similar to the one-day adjustment made to the Gregorian calendar every 400 years.

Because the Islamic year is shorter than the Gregorian year, Islamic months occur either ten or 11 days earlier in the solar year than they were the year before. The entire cycle of days between the two calendars takes about 32.5 solar years (33.5 lunar years) to complete.

Another effect of the shorter lunar year is that the gap between the two calendars is narrowing. The year 2003 on the Gregorian calendar was the year 1424 on the Muslim calendar (or most of it was!). The original difference between the two calendar years has narrowed from 622 at the start to 579 at present. The gap will continue to close. Years showing on the two calendars will momentarily coincide on the first day of May in the year AD 20,874 which will also be the first day of the fifth month (Jumada al-awwal) of the year 20,874 AH on the Islamic calendar. After that, the Islamic calendar will show more years than the Gregorian. Or perhaps by then, both calendars will have ceased to exist.

For those who need to know what day it is, Saudi Arabian timekeeping has an additional complication. In line with ancient practices, the official start of the new month is determined by the sighting of the new moon rather than by the number of days that have elapsed since the month started. For a new month to start, the crescent sliver has to be observed not merely by some ordinary mortal but the particular mullah in a particular observatory.

Sighting the New Moon

Until the official eye has observed the new moon and broadcast this news to the community, no new month can start. Words from the website of Dr Monzur describe the drawbacks of this method:

‘Islamic months begin at sunset on the day of visual sighting of the lunar crescent. Even though visual sighting is necessary to determine the start of a month, it is useful to accurately predict when a crescent is likely to be visible in order to produce lunar calendars in advance. Although it is possible to calculate the position of the moon in the sky with high precision, it is often difficult to predict if a crescent will be visible from a particular location. Visibility depends on a large number of factors including weather conditions, the altitude of the moon at sunset, the closeness of the moon to the sun at sunset, the interval between sunset and moonset, atmospheric pollution, the quality of the eyesight of the observer, use of optical aids etc. Since ancient times, many civilisations and astronomers have tried to predict the likelihood of visualising the new moon using different ‘minimum visibility criteria’. However, all these criteria are subject to varying degrees of uncertainty.’

As official literature on the subject describes, the new month may not begin on time for a hundred different reasons: the skies above the official astronomer may be cloudy, the telescope could be out of action, the official astronomer may have mislaid his glasses, and so on. Months may start a day or two behind schedule, which can play havoc with schedules of all sorts.

The problem is felt most acutely during Ramadan, the month everyone wants to end at the earliest possible moment. Without the official observation from the official observer, Ramadan continues, and Eid-el-Fitr—the holidays of feasting–cannot begin. This unpredictability of the religious culture plays its minor havoc in the modern world, particularly at airports. Though airports operate on the Gregorian calendar, support services may not. Day one of Eid-el-Fitr is not a good date to plan your exit from the country.

The 12 lunar month Muslim calendar runs as follows.

First Month |

Muharram |

Second Month |

Safar |

Third Month |

Rabi’al-awwal (Rabi’ I) |

Fourth Month |

Rabi’al thani (Rabi’II) |

Fifth Month |

Jumada al-awwal (Jumada I) |

Sixth Month |

Jumada al-thani (Jumada II) |

Seventh Month |

Rajab |

Eighth Month |

Sha’aban |

Ninth Month |

Ramadan |

Tenth Month |

Shawwal |

Eleventh Month |

Dhu al-Qi’dah |

Twelfth Month |

Dhu al-Hijjah |

All but one of the holidays in Saudi Arabia are observed on specific days of the Muslim calendar. The exception is Saudi National Day which is observed on a specific day of the Gregorian calendar (23 September).

Public Holidays in Saudi Arabia

1 Muharram |

Islamic New Year (First day of Muslim Calendar) |

12 Rabi’al-awwal |

Birthday of Prophet Muhammad |

1 Shawwal |

Eid-el Fitr (Feasting at end of Ramadan) |

Variable date |

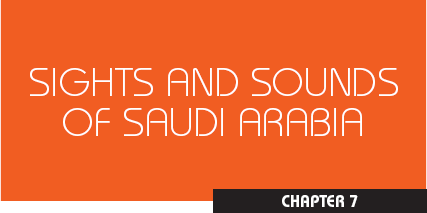

Jenadriyah National Festival (Festival lasts about ten days and celebrates the founding of Saudi Arabia by King Ibn Saud) |

23 September |

Saudi National Day |

19 Dhu al’Hijjah |

Eid al-Adha (Feasting day celebrating the pilgrimage to Mecca and the sacrifice by Abraham of his son) |

Since the Islamic calendar is based on the 354/355-day year, from one year to the next, on the Gregorian calendar each of these holidays (except Saudi National Day) is either ten or 11 days earlier than the year before on the Gregorian calendar.

The austerity of the Arabian Peninsula contrasts with the splendours that history supplied on the other side of the Red Sea. Despite Egypt’s proximity, no one built pyramids in Arabia. Nothing was built to compare with the Hanging Gardens of Babylon just over the northern border. With no administrative focal point in the region and little permanent agriculture, the nomads of Arabia lived on the move, leaving only limited physical evidence on the landscape to mark their passage. Nevertheless, with the antiquity of its civilisation and the incessant travelling of the Bedouin, pottery remnants are commonplace across the desert sands. A fossicking trip into the desert often yields something of historical interest.

Likewise the conquerors of the Arabian Peninsula who came and went left behind them only a few physical structures. Of the foreign invaders, the Turks established permanent footholds that have lasted through to the present day. The low forts and houses they built had thick walls and slits for windows to deal with the heat. On both coastlines, coral was the principal building material and usually coated with a hard lime plaster. Further inland, mud brick buildings are found in the central Nejd Plateau. Buildings up in the mountainous regions, where rainfall is higher, are built with stone plastered over with mud or lime. Only a few major stone buildings, of which the Grand Mosque of Mecca and the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina are the standout examples, bear testament to the splendours of Arabia’s finest hour—the Islamic empire of the Middle Ages.

At the beginning of the 20th century, only a few trading posts dotted the gulf coastline. Jeddah, Mecca and Medina were the settlements of the west. Riyadh was an oasis township surrounded by low mud brick walls.

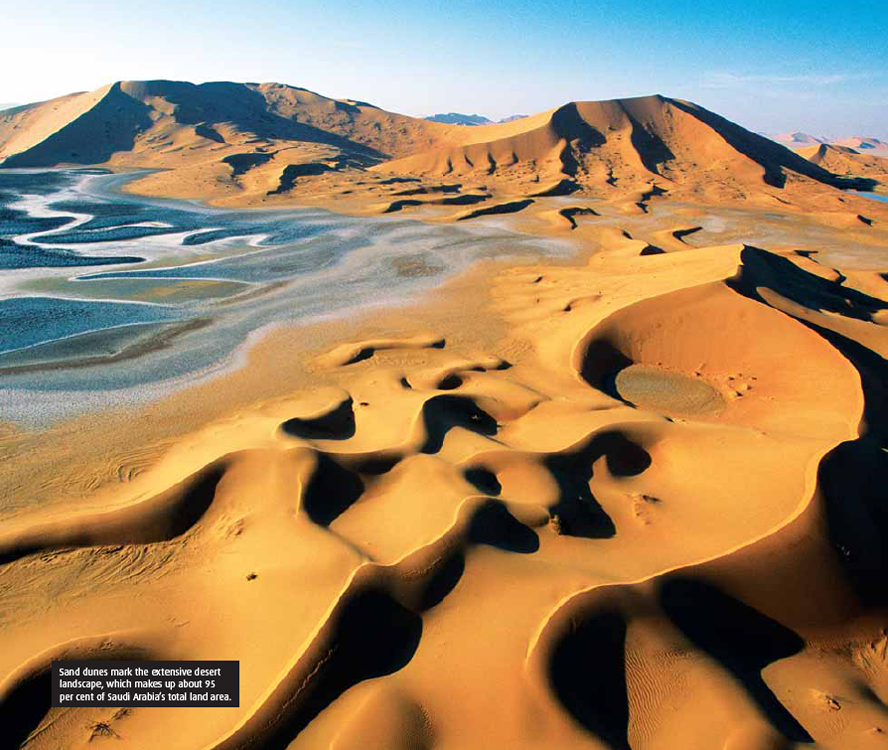

Most of the infrastructure of Saudi Arabia has been built in the last 50 years. With the globalisation of architectural standards, the downtown parts of Saudi cities—made up of high-rise buildings—may remind you of any place you have ever been. Yet, architectural design elements that are distinctly eastern convey an Arabic flavour that reminds you where you really are. Saudi Arabia has some spectacularly graceful buildings combining spires, minarets, domes, and highly decorated arches that are all unmistakeably Arabic. Stylised arabesque calligraphy and intricate geometric carvings are worked onto external surfaces. Domes in striking blue, green, yellow or gold make interesting features. Ochre renderings in red mixed with brown and white complement the austere desert surroundings and soften the harsh desert light.

The past and the present. The remnant mud-dwellings (left) in the city of Dir’iyyah, the first Saudi capital, is a far cry from the modern architecture (right) that can now be seen in the kingdom’s current capital of Riyadh.

Amongst buildings worth seeing in Saudi Arabia are the King Khaled International Airport, the Ministry of the Interior building the Kingdom Tower and the Al Faisaliah Tower in Riyadh, and the Humane Heritage Museum in Jeddah. Various mosques built along traditional lines, with minarets and slender towers, are also lovely buildings. The finest mosque of all—the Grand Mosque of Mecca—is unfortunately off limits to all but card-carrying Muslims.

The country is not known for its antiquities since so few permanent structures were built. The largely nomadic ancestors didn’t leave a lot of physical remains behind to mark their passage through life. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia does have a few museums of good standard. Principal among them is the Riyadh National Museum in the Department of Antiquities office. Displays at the Riyadh Museum are the history and archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula from the beginnings of settlement through to the golden age of Islam. Jeddah also has a couple of museums worth visiting if you are in the area—the Municipality Museum and the Museum of Abdul Raouf Hasan Khalil. The former is in a restored traditional house and is the only surviving building of the early 20th century British Legation in Jeddah. (In 1917, T E Lawrence, aka Lawrence of Arabia stayed at the Legation.) The Museum of Abdul Raouf Hassan Khalil is a private museum and has over 10,000 items displayed in four houses.

Some time in the 8th century, paper made its way from China to Baghdad and from there to the rest of Arabia. A paper mill was built in Baghdad around this time. Later, the Arabs introduced paper to Europe, trading it for scarce metals. In the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, the printing and publishing of the Qur’an and other religious and philosophical books were important industries that serviced the period when the Arab dominions led the world in science, mathematics, astronomy and medicine.

The Mongol conquest in the 13th century started the decline of Arab literature. Later during the Ottoman conquest, Arab literature took flight in Egypt and Lebanon. Reverting to its Bedouin ways, Saudi Arabia lost its culture of literacy. Nomadic Bedouins travelled light, relying on oral traditions of storytellers reciting tales. Paper did not return into Saudi Arabia in significant quantities until the 20th century. Though the kingdom is not noted for an enormous volume of literature, arguably its best known publication, the Qur’an, is the most influential book of all time. Outside Medina, the government runs a giant press printing around 10 million Qur’ans each year in 40 languages. The books are distributed free throughout the world.

In recent times, novelists writing about life inside contemporary Saudi Arabia are bound by the same strictures as the rest of society. Saudi Arabia is not a country where critics of the system fare well. In the case of popular Saudi novelist Abdelrahman Munif, not only was his Cities of Salt trilogy banned for being critical of the House of Saud, but the author was stripped of his Saudi nationality as well!

Like literature, other outlets for artistic expression are also controlled. In a country run by clerics, it probably comes as no surprise that the clergy determines the rules of painting. Once more the Qur’an has something to say on this subject. Images of real objects are not favoured. You will see no pictures of sweeping desert scenes hanging in Saudi houses. Saudi custom prohibits the painting of what are loosely described as naturally occurring objects—people, animals, or scenery in general. Saudi art is restricted to calligraphy and its extensions, of which there are some fine examples. In Arabic, letters and geometrical shapes that look like letters weave intricate patterns that are unmistakably Middle Eastern. Saudi art with its geometrical patterns tends to resemble Eastern carpets and vice versa. Such art is liberally applied to many surfaces—plates, canvases, plaques, tiles, textiles, sculptures and wall hangings.

The rules of the clerics also fashion the performing arts. It hardly needs to be said that female dance is prohibited in Saudi Arabia. The Royal Ballet never books Riyadh on its tours of the world. No performance of Hair is ever likely to be staged in the kingdom. However, performance of Saudi Arabia’s traditional dance, the ardha, is allowed. This dance has military origins and features barefooted males clad in their normal street clothes of thobe and gutra jumping up and down mostly in one spot while wielding swords. Parents be warned! This is not a dance that should be performed by your own children in your own home.

Music is not banned in the kingdom. On the other hand, no visiting rock band has been known to perform in Saudi Arabia. But the dictates of the Qur’an do allow some forms of traditional music to be performed. Arabian music is probably an acquired taste. The traditional musical instruments of Saudi Arabia are those of the Bedouin—the tambourine (rigg), drum and stringed instruments—the oud and the rebaba, which muster four strings between them. Another interesting traditional song and dance known as the al-mizmar is performed in Mecca, Medina and Jeddah. The dance features the music of the al-mizmar, a woodwind instrument bearing the same name as the dance and similar to the oboe.

Saudis making music with traditional instruments.

Since tourist facilities are underdeveloped in most Saudi cities, finding your way to a building you have not visited before is not easy. Streets are poorly sign-posted if at all, and addresses are not well numbered. Street directories are nonexistent for most places, though street maps may be available for the larger cities. Even if street maps are available, many of the minor streets and alleys will not be marked. Since street names are poorly marked and difficult to read with poor language skills, a common sort of direction from the person you are visiting is likely to be: “I live in such and such street opposite such and such a landmark.” Before setting out on a journey you haven’t made before, it’s a good idea to make your own map if you can, including marking on it some prominent landmarks by which to navigate. GPS systems are very helpful though not always infallible.

Not all that many guest workers bother to go sightseeing when in Saudi Arabia. Many never journey further astray than the road between their compounds and the nearest airport. If they travel within the country at all, they usually do so by air.

However, driving over the nation’s highways is an entirely practical adventure. Saudi Arabia is a large country and sparsely populated between its major cities. Travel by car is swift. Motel-style accommodation is reasonably available. Failing that, more adventurous spirits can camp under the stars, which are spectacular away from the towns.

The countryside has its own austere charm, but the normal precautions of desert travel apply. Don’t stray far off major roads. Preferably, travel in convoys of at least two vehicles in case of accidents. Take spare parts such as fan belts, engine oil, petrol and water. In case you get stranded, take food rations plus plenty of drinking water. Take some warm clothes too—the desert airs can get chilly at night. And take plenty of documentation that will testify who you are.

Except for off-limit religious areas like Mecca, you are free to travel wherever you wish, though you are meant to carry appropriate documentation. On your travels you should carry your Iqama plus a letter from you employer authorising your travel and authenticated by an immigration official or a Chamber of Commerce office. If driving, also carry a full set of insurance documents for yourself and your vehicle.

Rules are always changing (and may do so while you are in transit!). People who want to travel should ascertain the appropriate travel documentation before commencing their journey. In theory at least, those who get caught without the appropriate paperwork and can’t convince the arresting officer to take a lenient view, are liable to Saudi Arabia’s customary punishment—imprisonment for an unspecified period.

Once en route to your destination, you pass through countryside that holds few surprises. You are picked up from, say, King Fahd Airport in Damman in the Eastern Province. In the town itself, a few eucalypts—now the world’s most ubiquitous tree—line the sidewalks. (Eucalypts seem to be the tree in general global use for areas in which no other tree will grow.)

If you happen to be driving through the heat of the day, the light is intense. Passing out of town, you drive past rock formations that may well remind you of pictures beamed from the Sea of Tranquillity by Apollo astronauts: geologically interesting and quite appropriate as a moonscape; but for earthbound mortals, starkly austere. Further out of town, bare rock gives way to deserts of small dunes. The eastern side of the country is flat and monotonous.

From Damman, you can head up the eastern highway north towards Kuwait, through Jubail and Ras’al Khafji. The other choices of highways from Dhahran are south through the oasis town of Al Hufuf towards the UAE, or west through Riyadh to the Red Sea coast.

Roads in Saudi Arabia are elevated to prevent sand building up on the bitumen surface. The surface is high enough that the sand is blown across the road instead of being deposited. Incidentally, driving through a sandstorm is not advised. Not only is visibility reduced to near zero, but the wind-driven sand can eat up your paintwork very rapidly.

Whichever way you are travelling, the initial scenery is similar. In the first part of the journey, the road passes through the coastal plain, low dunes that are flat and featureless. The black road snakes ahead over a pale orange landscape. Perhaps you will see an occasional palm tree or perhaps the low dunes may sport sparse tufts of marram grass. Here and there amongst dunes, the flared gas of an oil well shoots a tongue of red flame and a contrail of dirty gas into the sky. But mostly the vista is endless sand in various shades of yellow, orange and red.

The most interesting landscapes as well as the major historical icons are to be found in the western half of the country, in particular the south-west. As you head west, the landscape crinkles into the ranges that run along the western seaboard. Towards the Yemen border, the road winds through high hills and relatively fertile valleys atypical of the rest of the country. To the north, the highway heads up to the Jordan border, sometimes through rolling arid countryside, sometimes along the coastal plain.

Riyadh is the capital of Saudi Arabia with a population of nearly 5 million. Riyadh took over from Jeddah as Saudi Arabia’s most important and largest city in the 1970s. The city is a stronghold of religious zeal. Wahhabism had its origins in this area. The Committee for the Preservation of Virtue and for the Prevention of Vice, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and the Mutawa’een have their headquarters here.

The city sits in a basin surrounded by barren mountain ranges. It is sited on one of Saudi Arabia’s largest oases formed at the confluence of three underground rivers, called wadis. In past eras, desert travellers sought Riyadh as a welcome staging post of trees, gardens and parks in the centre of a vast desert. Desert travellers could trade their wares for dates and other fruit from Riyadh’s ample gardens. Today, the city is still known for its greenery, though not enough underground water is now available to sustain either its population or its vegetation. Riyadh is supplied by desalinated water piped from Jubail, 400 km (290 miles) to the east, through one of the world’s largest water pipeline systems.

One hundred years ago, Riyadh—surrounded by low sandstone walls—was a city small enough to be conquered by King Ibn Saud and his 40 stalwarts armed with the best in breech-loading rifles the British arsenal could supply. Today, remnants of the old city walls remain as a tourist attraction. But the modern city has sprawled well beyond its original boundaries. It is a modern city, having been substantially built from the 1960s. From an oasis in the more traditional sense, Riyadh has become an oasis of high-rise. The infrastructure and standard of accommodation and facilities is good. Being near the centre of the Arabian Desert, the city is hot in summer and cold in winter, and subject to a wide temperature range between day and night. Sand storms are prevalent in the spring.

Jeddah (alternatively spelt as Jiddah) is the commercial capital of Saudi Arabia and the country’s second largest city with a population of over 2.8 million. Jeddah is the kingdom’s major seaport and dates from pre-Islamic times as a fishing settlement which later became a transit point for the spice trade and a gateway to Mecca. During the centuries of occupation by the Ottoman Turks, Jeddah became a fortified walled town. Fragments of the original city remain, though 20th century developers demolished most of the historical structures as a source of building materials.

Jeddah’s most famous landmark is the floodlit corniche that separates the main commercial area from the Red Sea coast. The city also features what is claimed to be the world’s tallest fountain and some bizarre sculptures that are worth seeing including a giant steel fist mounted on a granite block, a penny farthing bicycle as high as a four-storey building and crashed Cadillacs sticking out of a three-storey high building and featuring tail lights that illuminate at night.

As Saudi Arabia’s most cosmopolitan city, trade through Jeddah has, to a degree, eroded the religious strictures of Saudi Arabian theocracy. Jeddah is about as free and easy as it gets in Saudi Arabia.

Taif, Saudi Arabia’s ‘summer capital’ is located in the Hijaz Mountains, a spectacular two-hour drive from Jeddah. Standing at about 2,000 metres (6,000 ft) elevation, Taif has a pleasant year-round climate with mild summers (25–30°C / 64–90°F) and cool winters that sometimes get below freezing. The normal population of Taif is around 400,000. Population doubles during summer with an influx of vacationers escaping the heat elsewhere in the country. Taif is a typical Saudi Arabian city of contrasting old and new. Glass-clad modern buildings, several stories high, rise cheek by jowl with the old mud plastered stone structures with wooden louvred windows and carved wooden doors. The city is located in the high rainfall area of Saudi Arabia (around 400 mm or 16 inches annual precipitation). As a result, the surrounding countryside is less barren and supports agriculture, in particular vegetable gardens. The traditional Bedouin souqs are well known amongst collectors of Bedouin wares such as pottery, jewellery and carpets.

Mecca, Islam’s holy city with a population of 1.5 million, is a jumble of high-rise buildings. Fast growth in religious tourism from overseas pilgrims who can afford airfares into Saudi Arabia has propelled land prices in Mecca to amongst the highest in the world.

Mecca is the major tourist attraction to the Muslims allowed to go there. In developing Mecca, the Saudi municipal authorities have not been particularly fussy about preserving their antiquities. On the hill of Ajyad district, an 18th century Ottoman Fort—built as a defence against Wahhab maurauders—has been demolished to make way for seven apartment towers, six huge hotels and a four-storey shopping centre. In the Mount of Omar District, developers plan to clear many of the old buildings and build 120 residential towers, each 20 stories high and able to accommodate a total of 100,000 people. A further five massive development projects, if completed, will add 50 per cent capacity to Mecca’s housing market. Facing the gate of the Grand Mosque, Saudi bin Laden, Saudi Arabia’s largest construction company, has built the Abraj Al Bait Towers, a building complex that houses the Mecca Royal Hotel Clock Tower, the kingdom’s tallest building.

Medina, with a population of around 1.3 million, is Saudi Arabia’s other holy city. Situated about 400 km (250 miles) north of Mecca, Medina is the city to which the Prophet Muhammad retreated after he was persecuted by the establishment at Mecca, and which later became his burial place. For that reason, it is an important destination for religious tourists. The city is situated on a plateau, about 700 metres (2,300 feet) in elevation, in the low mountain range that runs along the western seaboard of the country. Medina’s most important building is the Prophet’s Mosque. South of Medina and worth a visit for historical interest are the plains of Badr, the battlefield where Muhammad fought his most successful campaign against the army of his Meccan enemies.

Dammam and Al Khobar are separate townships that have joined at the edges. The third adjacent town, Dhahran—the site of the first of the country’s oilfields—was built mostly by Aramco as accommodation for the oil workers who developed the oil installations on the country’s Eastern Province. Dammam, Al Khobar and, to a lesser extent, Dhahran can be regarded as a single settlement. The cities, built on the Persian Gulf shore, have a long history as trading posts. They are an interesting mixture of the old and the new, with souqs and crumbling mud-brick structures giving way to shopping malls and high-rise.

Most hotels in Saudi Arabia are in the mid- to expensive range. Hotels in Riyadh are usually slightly less expensive than those found in many major European cities. Budget hotels can also be found in Saudi Arabia but, generally speaking, the bottom end of the hotel market is not well served. This is not a country to which backpackers flock in droves. The best information to be had for the low end of the market is to be found in publications like the Lonely Planet series. Hotel information for those making hajj and umrah pilgrimages may be obtained from tour operators specialising in this business or at websites such as http://www.islamic-travel.ch/. For more general information on all classes of hotel accommodation, try:

http://asiatravel.com/saudi/index.html

http://asiatravel.com/saudi/index.html

http://www.hotelstravel.com/saudi.html

http://www.hotelstravel.com/saudi.html

By the time Saudi Arabia got around to developing its infrastructure, air travel was well established over most of the planet. Having made the great leap forward from the 10th century to the 20th century in a single bound, and jumping right over the 19th century in the process, Saudi Arabia never got around to developing a rail system of any consequence. Instead, they built roads and airports.

The total length of rail in the country is less than 2,000 km. The major railway line is that between Riyadh and Dammam which is used almost exclusively for freight. But that could change in years to come if the government carries through its rail development plan by building new lines. On the drawing board is a cross-country rail network with links between Riyadh and Jeddah (945 km or 587 miles); Dammam and Jubail (115 km or 71 miles); Riyadh and the Hudaitha border post with Jordan (610 km or 379 miles); and Mecca and Medina (425 km or 264 miles).

A site of interest for Lawrence of Arabia enthusiasts is the Hijaz railway built by the Ottomans that connected Damascus in Syria to Medina. Lawrence and his troop of Bedouins blew it up during World War I on the Jordanian side of the border. The event was famously depicted in the 1962 movie, Lawrence of Arabia. Remnants of the railway, opened in 1901 and shut down in 1915, are still visible on the Saudi side.

According to the CIA website (which provides the most easily accessible statistical thumbnail sketches of the countries of the world), in the year 2010, Saudi Arabia had 217 airports, including military airports. Of these, three are international airports, located at Riyadh, Damman and Jeddah.

The national airline of Saudi Arabia is Saudi Arabian Airlines (Saudia), which operates both domestic and international services. In its earlier days, Saudia earned a reputation for eccentricity within the industry. In the 1960s and 1970s, it suffered a rash of minor but newsworthy accidents. Stories, possibly apocryphal, circulated of travelling Bedouins attempting to barbecue their own meals in the aisles while the planes were airborne and pilots taking their hands off the controls during electrical storms and leaving things to fate. Since those days, the safety statistics of Saudia have been excellent. The airline has earned itself a Rating 1 on the US Federal Airports Authority’s safety assessment programme.

Local Rules on Flying

Saudia still maintains its reputation as an anachronistic airline. No alcohol is served on Saudia flights, either within Saudi Arabian airspace or internationally. During the daylight hours of Ramadan, packaged food is handed out, but cannot be eaten. The cabin crew advises passengers to take the food off the plane and eat it after dark. In addition to the normal pre-take off safety features announcements, after the safety features are identified and prior to take-off, a video is screened offering prayers for a safe trip. The policy seems to be working. No planes have crashed in recent times.

Air travel within the country on Saudia is configured for business passengers rather than the economy class tourist industry that is more common in other parts of the world. Other than conveying Muslims to their religious destinations, demand for tourism class airflight within Saudi Arabia is limited. Flying around Saudi Arabia by Saudia is considered expensive by international standards. According to one account, one reason for this is that minor Saudi princes have developed a practice of flying liberally within the kingdom, displaying their royal credentials to booking staff, rather than buying a ticket. The revenue shortfall from this act of royal self-indulgence is recovered as a ‘royalty’ levy from less distinguished passengers. This is supposed to be one reason for the higher ticket prices.

The principal industry in Saudi Arabia is oil. A trivial pursuit question guaranteed to stump all but the most inveterate Middle Eastern buffs is the identity of the country’s second biggest industry.

The answer is—tourism.

One hundred years ago, Saudi Arabia was among the least visited countries on the planet. Apart from the Turkish conquerors in residence at the time, there was only one strong reason for anyone to visit this featureless piece of desert roamed by some of the world’s poorest people. That was the annual pilgrimage to Islam’s holy shrine of Mecca—the month of Dhu al-Hijjah, the last month of the Islamic calendar and the month from which the hajj gets its name. One of the five pillars of Islam, the hajj stipulates that believers, both local and from foreign lands, should participate in this once-in-a-lifetime voyage. Non-Muslims, in contrast, are banned from Mecca on pain of death.

The Hajj Business

In recent years, businesses associated with the hajj pilgrimage have become the fastest growing sector of the economy, employing four times as many employees as the oil industry. The number of hajj pilgrims was about 2.5 million in 2011. As this number is expected to rise in the coming years, the governments of Mecca and Medina are gearing up for this by increasing building projects in the holy cities. Since Islam is now a global phenomenon, and with the easy availability of air travel, the yearly influx of pilgrims has expanded past anything that could have been envisaged by Islam’s founder. With outgoing Saudi tourists taking less extensive and expensive trips outside the kingdom, tourism became a net positive industry on Saudi Arabia’s national balance sheet in 2002. A study published in 2007 estimated that the revenue from hajj and umrah could jump to 18 billion SAR (about US$ 5 billion) in the next ten years.

Like many of its ideas, Islam adopted the hajj from older religions. Pilgrimage to Mecca is an ancient rite and long a mainstay of the Meccan economy, extending well into pre-Islam days. The star attraction then (as it is today) was Islam’s most sacred icon, the Hajar ul Aswad, the black stone of Mecca.

A hajj pilgrimage is quite unlike most people’s idea of a holiday. Each pilgrim must perform a series of most intricate rituals performed in strict chronological order, and at certain days of the holy month. Pilgrimage is hot, tiring and hazardous work. Mandatory pilgrim activities include hours of walking, a great deal of praying, much queuing and incessant crowds.

Pilgrims are required to perform a number of rituals during the hajj, largely symbolic of Abraham’s journey in the desert. Pilgrims must cut their hair at the appropriate time and to the appropriate length. They must throw pebbles at the Jamrah— three stone pillars—a certain number in the correct order and at particular times. (The stone pillars are meant to be symbols of evil. Bombarding them with pebbles is thought to purge the stone thrower of whatever evil resides in the pilgrim’s soul.) Pilgrims must also touch the sacred Hajar ul Aswad and walk around its containing structure, the Ka’abah, a prescribed number of times in certain directions. Live animals must be sacrificed according to methods specified by the Prophet. (Saudi Arabia imports six million live sheep each year to be slaughtered at Mecca for this purpose.) Between these activities is interposed a great deal of praying. The entire process takes up to two weeks, with the result that Mecca gets pretty crowded during the pilgrim season.

Throughout history, merchants around Mecca have made a living from the once-yearly influx of tourists. Local commercial tradition seems to demand that pilgrims are fleeced in one way or another while on their pilgrimages. Non-Arab pilgrims from countries like Pakistan, Malaysia or Indonesia— foreigners who are unfamiliar with local customs and prices—are particularly targeted since they can be overcharged with little resistance. More indirect means are also applied to relieving pilgrims of their money and their possessions. One of the requirements of the pilgrimage is that pilgrims must leave their possessions behind in a camp somewhere on making the final leg into the Grand Mosque. This is an opportunity for pilfering (though the more savvy pilgrims discretely wear money belts around their bodies).

As well as that, during a pilgrimage, the pilgrim faces a number of physical hazards to life and limb. For example, the pillars of evil, the Jamrah, are contained in a pit surrounded by a low stone wall that can be approached, and stoned, from all points of compass. On occasions, poor aim and overzealous throwing have taken out a number of fellow pilgrims standing on the opposite side of the pit. Another risk is being crushed by crowds of excited individuals pressing forward against the circular wall in which the Jamrah resides. Over the years, large numbers of pilgrims have been crushed or stoned at this site with fatal results.

The gathering of tribes with historical enmities also raises tensions. Pilgrims from within Arabia itself may come from other tribes with whom the natives of Hijaz are traditionally not on speaking terms. Shi’ite pilgrims from countries like Iran are denounced as heretics by the extreme elements of Saudi clergy. Many Shi’ites have been officially executed over the years as a result of their pilgrimages, and others have been killed more casually. In 1991, the Saudi papers quoted Abdallah bin Jibreen, King Fahd’s appointment in clerical ideology, describing Shia believers as ‘idolaters who deserve to be killed’. In making their pilgrimages, Shi’ites are venturing into enemy territory.

Open warfare had broken out on occasions. In November 1979, after the Shia inspired revolution in Iran, a force of about 300 Wahhabi fanatics led by religious activist, Juhayman Otteibi stormed the Grand Mosque of Mecca in a bid to overthrow the Saudi Royal Family and start an Islamic revolution. The dissidents charged that corruption and close ties to the West had cost the Al Saud regime its legitimacy to govern. The fanatics held the mosque for ten days despite attempts by the Saudi military to recapture it. The situation was becoming internationally embarrassing and the Saudis called in overseas support. French paratroopers regained control, first by flooding the Grand Mosque, then by electrifying the water. More than 100 fanatics and 127 Saudi police died in a shoot-out. Surviving dissidents and suspected dissidents were later publicly beheaded throughout the cities and towns of Saudi Arabia. For the benefit of those unable to attend these beheadings in person, executions were broadcast live on Saudi TV.

In July 1987 Iranian Shi’ite pilgrims to Mecca clashed with Saudi police and the casualty list from the engagement numbered 400 killed with many more injured. After a further riot of Shia pilgrims in 1989, Saudi Arabia cut off diplomatic relations with Iran.

Some pilgrims to Mecca escaped death at the hand of man only to succumb to the hand of God. In 1990, a tunnel packed with pilgrims collapsed resulting in a total death toll of around 1,400. A further 270 pilgrims died in 1994, crushed in an accidental stampede. In 1997, about 340 Muslim pilgrims were burned to death when their campsite near Mecca caught fire. Two more stampedes during the stoning ritual in 1998 and 2001 saw a further 150 pilgrims killed.

In view of the recurring high casualty rate, Muslims from countries outside Saudi Arabia have queried whether Saudi Arabia has the infrastructure and organisational skills to host the annual influx of pilgrims. But the pilgrimages continue. Despite the hazards, the number of pilgrims increases each year. Some travel agents in Islamic countries outside the kingdom specialise in hajj tourism. Kuala Lumpur, for example, has a multi-storey building dedicated to arranging hajj tours for its pilgrims. Travel agents offer their Muslim clients a full 14-day Mecca/Medina experience, including detailed guides on how to discharge their hajj obligations. Package tours offer the obligatory rituals at Mecca along with side trips, such as visiting Muhammad’s tomb at Medina. Guided tours take the pilgrims to the various religious sites at the appropriate times.

With the hajj now a major industry involving millions of customers, far more people arrive to perform their hajj obligations than the holy icons at Mecca can easily accommodate. Given the overwhelming demand for the hajj from rapidly expanding Muslim populations across the globe, the intricate rituals that pilgrims undertake at various sacred icons have become bottlenecks. Management studies have been conducted to investigate ways of speeding up pilgrim throughput. Saudi authorities have encouraged religious scholars to be more flexible in interpreting pilgrims’ religious obligations.

One obvious measure that could be taken is to extend the pilgrim season. The basis for this idea is the umrah, which is a simplified version of the hajj. While the umrah incorporates many of the elements of the hajj, it is not accepted as the full substitute. But the umrah has great advantage over the hajj in that it can be performed during the entire year. According to The Economist, umrah travel is now growing at 10 per cent annually with three-quarters of a million umrah pilgrims coming from Egypt to visit the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

To expand facilities for pilgrims and ease the burdens of pilgrimage, the Saudi government has spent more than US$ 35 billion since the mid-1960s in improving infrastructure at Mecca. Despite these improvements the government has been forced to restrict the number of tourist visas it issues. Each Muslim nation has a quota of about one hajj visa for every 1,000 Muslim citizens, meaning that during the course of their lives, Muslims have only a 4 per cent chance of fulfilling one of the pillars of their faith. Despite the difficulties, the risks and the costs, the demand for pilgrimages exceeds the availability of visas. Not only is the hajj one of the five pillars of faith, becoming a hajji, the term for a pilgrim who has successfully performed the hajj obligation, is also a badge of honour.

While demand for Muslim pilgrimage has reached saturation point, the same cannot be said for inward tourism more generally. In fact, by making things difficult for its visitors, Saudi Arabia has ensured only the most dedicated non-Muslim tourists are likely to visit the kingdom. Entry qualifications are stringent. You need to find someone inside the kingdom to sponsor you. Your travel plans must be ‘approved’. Only approved destinations can be visited. Your travel will be chaperoned to some degree. The paper chase of visas and permissions prior to your trip will be exacting and laborious. But assuming success, you may then make an officially sanctioned trip to the kingdom, to be taken on an (expensive), controlled, but nonetheless interesting, ‘approved’ tour.

One of the great cultural contributions the USA has made to the world has been the invention of R&R (Rest and Recreation) leave. For Western expatriates, most employment contracts in Saudi Arabia will have an R&R component. Typically, two R&R leave entitlements of about 10–14 days are allowed each year, in addition to annual leave. Under most employment contracts, R&R must be taken outside Saudi Arabia. Within reasonable limits, the company gives you an air ticket to the destination of your choice. This is a terrific opportunity to see some interesting parts of the world at someone else’s expense.

Saudi Arabia happens to be very centrally situated to many attractive and interesting R&R destinations. It is also within range of places that make an intriguing weekend away. Cairo, Beirut, Damascus, the history-packed islands of the Mediterranean, Cyprus, Crete and Rhodes are all within easy reach. Most of South-east Asia, most of Africa, all of Europe, the other countries of the Middle East and Russia are within a chronological diameter of nine hours flying time. In terms of travelling to somewhere else, Saudi Arabia is central. Though North America is a little out of reach, non-stop flights are available to east coast cities.

The easiest country of all to get to from Saudi Arabia is Bahrain, which is now connected to the kingdom at Dammam by a 25-km causeway. Taking a holiday in Bahrain may not sound all that exciting to some, but attractions are relative. Many on the east coast make the journey to partake of two of Saudi Arabia’s forbidden fruits—pork and alcohol.

But the Saudi immigration authorities have also heard of the availability of pork and alcohol in Bahrain. They are diligent in ensuring these prohibited items do not make the return journey across the causeway. At the checkpoint between Saudi Arabia and Bahrain on the causeway connecting the two, immigration authorities customarily perform rigorous checks of all vehicles inbound into Saudi Arabia. Standard procedure is to use mirrors to check the underside of the car for packages bolted to the underside of the body pan.

Such has been the influx of Saudis into Bahrain after the causeway was completed, and such has been the attendant collateral damage by single alcohol-impaired Saudi men, that for a while five-star hotels in Bahrain restricted its bookings to Saudi families only. The worst time to travel to Bahrain via the causeway is Thursday morning when long delays at the border crossing points can be expected from Saudi weekenders heading for their rest and relaxation activities in Bahrain. For the same reason, the return trip on Friday evening also tends to be congested.

Paying Attention at the Border

As in all things in the kingdom, a greater than normal level of care can keep you out of trouble. But lapses of concentration are human nature. A British sales executive of ‘African and Eastern’ (one of the three authorised distributors of alcoholic beverages in Bahrain) had a sideline business in soft drinks inside Saudi Arabia. To service this business, he would drive his own car across the causeway into Saudi Arabia. While in Bahrain, he customarily carried a sample of his company’s products—a case of beer—in the boot of the car. One day, he travelled to the kingdom at short notice and forgot about his samples. At the border, Saudi immigration officials found the beer. The sales executive was first jailed, then fired from his job, and finally deported.

Further down the coast from Bahrain, is the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a coalition of seven emirates, the main three of which are Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Sharjah. By car or by taxi, any of the emirates is accessible from any of the others. Modern and progressive, the UAE, about a two-hour flight from east coast airports, is well worth a visit. As a base for a tour into the area, Sharjah or Dubai are probably the best places to stay. Both are very modern, attractive Arab-style city-states.

For the guest worker and dependents, air travel around the Middle East on regional airlines may involve an extra degree of uncertainty. The fact that you hold a confirmed booking may not guarantee you a seat on the flight. If an Arab passenger decides at the last minute that he wants your seat on one of the Middle East airlines like Gulf Air or Saudia, the chances are he will get it. You may be ‘bumped’ off the flight, a practice that is not entirely unknown in other parts of the world, but particularly prevalent in the Middle East.

One of the authors has had a personal experience at being bumped off a flight from Bahrain to Cyprus and, as a result, enduring a near-death experience from freezing in Bahrain’s extravagantly air-conditioned airport during a 24-hour wait for a ticket out on the next available flight. Expatriates tend to be bumped off flights in the reverse order of the Middle East racial hierarchy. Those with the least status, Asian and sub-continent nationals from Third World countries, will find themselves ‘bumped’ ahead of Westerners. On one Kuwait Air flight taken by one of the authors, the flight crew read out the names of four Filipinos who were asked to identify themselves as the flight, which had already been loaded, awaited to take off. Everyone knew what was going on. Not a soul admitted to their identities, but the individuals were identified from the passenger manifest, extracted from their seats and bundled off the plane to be replaced by four Arabs. Filipinos stick together. After the extraction was completed, the atmosphere in the plane crackled with resentment. A near riot broke out when the plane landed in Dubai, its next stop.

Saudis are sensitive about photo taking. If you do take photos, you may also be taking a risk. People, including one of the photographers for this book, have been thrown into jail for snapping pictures without holding the proper permits. Others have been jailed and held overnight just for carrying a camera. Yet others have taken all the photos they wanted and nothing happened. The law of the land is this: photo taking without a permit is against the rules and the source of permits that allow photos to be taken is not entirely clear. The only photo taking that is entirely legal is within someone’s home.

Some of the photo subjects that would cause particular offence are obvious enough. Saudi Arabia is sensitive to its strategic position in the world. You would not be well advised, for example, to photograph military facilities. Taking photos of potential industrial targets such as oil refineries and port facilities will not be well regarded. Religious icons are off limits too—Saudis are sensitive about their religious beliefs. Whatever might be interpreted as showing the country in a bad light are risky photographic subjects. Snapping of abayaclad women in the street is not recommended. Saudis know that the outside world views their treatment of women as regressive. There is an argument, too, that taking pictures of people or even scenery may violate provisions of the Qur’an concerned with recording images. Saudi art, which limits its subjects entirely to calligraphy, certainly seems to confirm that rendering natural objects as pictures is off limits. The safest photographic subjects are the country’s most splendid non-strategic structures such as soaring city skylines. Street scenes inside expatriate compounds are acceptable subjects. So are the natural landscapes and subjects like camels. Whatever the subject, picture taking shouldn’t be too overt.

Entertainment in Saudi Arabia is more restricted than in most countries. Activities such as gambling, drinking, a wide range of literature, card playing, socialising with the opposite sex (other than family) and various sporting activities that display too much skin, are, in theory at least, all off limits. Saudis rule makers regard life as a very serious business with a stringent behaviour code.

It was once said that the Puritans (a Christian sect prevalent in the 19th century in Europe) objected to bear baiting ‘not because it gave pain to the bear, but because it gave pleasure to the spectators’. Likewise of the laws of Saudi Arabia might seem, to Westerners, targeted at banishing pleasure as distinct from advancing social justice. Measures that seem to take the fun out of life for no obvious reason include banning music played over telephones that are on hold and jingles on mobile phones, banning sending of flowers by friends and relatives to patients in hospital and banning the children’s game Pokemon. Even chess is considered a questionable activity because of the possibly idolatrous nature of the pieces.

According to one interpretation, the Prophet declared all forms of entertainment off limits for a Muslim except breaking a horse, drawing a bow, and amusing himself with his wives. Perhaps this is the reason for the prohibition on seemingly innocent pastimes, though it has to be said the Prophet was silent on the matter of Saudi Arabia’s current favourite form of recreation—watching the national soccer team on TV.

Camel racing is probably the only uniquely Saudi Arabian sport whose mass popularity has survived into modern times. For thousands of years the camel has been the sine qua non of desert life: the source of transportation, milk, meat, leather, wool, shade, shade-cloth as well as sport. Camels are one of the few animals that can keep hale and hearty on the meagre offerings of the desert. Though domestic camels show preference for more exotic foodstuffs, camels can survive on anything that is even remotely suggestive of being vegetable fare, such as spinifex and thorn bush.

Though Saudi Arabia still contains plenty of camels living a traditional life as pack animals of Bedouin tribes, the country is now in the camel importing business. Some consider the best camels are those roaming in the wild over Australian deserts. These are the descendents of camels, originally from Arabia, that were brought to Australia in the 19th century to serve as pack animals to supply Australia’s outback settlements. According to Australian folklore, only the most robust and healthy camels survived the long sea journey, thus culling the weak from the genetic strain. When road and rail displaced camel trains in Australia, the animals were released, thriving to become the largest camel population in the world, and the only significant herd that runs wild with no human owner. Being isolated on an island, this herd may also be the most disease-free. Australian camels have been imported for racing in Saudi Arabia along with Australian know-how of improved husbandry and training methods.

The ship of the desert.

Camel racetracks have been built in most of the kingdom’s major centres. Races for prize money are held many weekends throughout the winter months. In the manner of racehorses, top dollar is paid for camels with breeding pedigree. Like horses, camels go faster with lightweights on their backs. Sad to say, Saudis have been known to engage jockeys as young as four years old, obtained from underprivileged countries like Bangladesh.

Horses, now raced for sport, have also played a key part in Arabian history. Horses were first thought to have been domesticated in about 4,000 BC, in the area of present-day Ukraine. One Bedouin legend offers an alternative account, claiming that the Arabian horse was God’s gift to Ismael, son of Abraham, as a reward for his faith. Whatever their source, after they were domesticated, horses later spread throughout Arabia, Central Asia and Europe. Civilisations became dependent on their horses for agriculture, transport and military activity.

Bedouins greatly treasured their horses, treating them as members of their household, thus ingraining in their horses a strong sense of loyalty towards their owners. Mares were especially prized because they were considered less temperamental than stallions and made less noise (thus not alerting the enemy during raids).

Arabian horses were bred for their fine features, speed and endurance, whereas the heavier European horses were developed for strength and carrying capacity. The Arabian horse was an essential aid to the spread of the Islamic Empire. With superior speed and endurance over other strains, Arabian horses have become the basis of the bloodstock industry worldwide.

Falconry, another sport with long traditions, is still enjoyed in the kingdom today. The apparently empty deserts offer sufficient small animals and birds to serve as prey, though overgrazing has reduced falcon populations in Saudi Arabia. Most falcons are now imported from neighbouring countries or further afield in Asia.

Originally falconry served as a way for Bedouins to supplement their diet with wild game. As in the past, today’s young falcons are taken from their nests, with the trainer becoming the surrogate mother. Once grown, the falcon is trained to perch on its trainer’s arm. Since they make better hunters, female falcons are favoured over males. Female falcons are bigger and stronger than males, are more patient and less temperamental, and are thought to have better eyesight. Falcons can live up to 15 years.

With the influx of guest workers into the kingdom came sports some of which have made and impact on the Saudi scene and some of which haven’t. The most popular imported sport is soccer, the world’s most popular ball game, which has well and truly caught the imagination of the Saudi public. Like many countries, Saudi Arabia has spent plenty of money developing its national soccer team, arguably the strongest in the region. The Saudi national team has reached four consecutive World Cup finals in soccer—1994, 1998, 2002 and 2006. The team did not qualify in 2010, and hopes were dashed again for the 2014 World Cup to be held in Brazil.

At the falcon market in Riyadh, pure-bred falcons can be traded for millions of riyals.

Basketball, introduced in the 1950s by guest workers from the United States is another imported sport. Though the game did not catch on for decades, basketball increased in popularity after the introduction of a government programme encouraging participation among schoolchildren and the construction of hundreds of courts.

Despite these programmes, participant sport is still not all that popular in Saudi Arabia. One possible reason is the climate. Another is the traditional clothing that Arabs wear. While registered sportspeople, like the Saudi football team, wear regulation equipment for their sport, casual players are often seen attempting to play sports in their street clothes— which are spectacularly unsuited to just about every sport ever invented. Injuries are commonplace amongst those who trip over the hems of their thobes while attempting to knock a ball around.

The Saudi Arabian national team before their qualifying game for the 2006 World Cup.

Clothing is even more of a problem for Saudis interested in beach sports. Despite a hot climate and warm water, Saudis are not known for their inclination to take a cooling dip. On beaches, normal Saudi dress code applies—a rule that sometimes leads to tragic consequences. A few years back, three Saudi women, who could not swim, drowned after getting into trouble at a beach north of Jubail. The women had entered the water fully clothed. They got out of their depth and were dragged down by their abayas, while their menfolk, similarly impeded, looked on helplessly from the beach.

The heat, the restrictions on displays of public enjoyment and the restrictions on dress code in public do limit the pastimes in which Saudis get involved. Since the Saudis are sociable people with strong family ties, a principal form of recreation for Saudi nationals is visiting friends and relatives and having family picnics. Bedouins leading urban lives take this idea a step further in maintaining their links with their traditional haunts. Families take vacations in the desert, setting up tents and spending a week or two reliving something close to the life of their parents or grandparents.

Guest workers who enjoy participant sports will find plenty of opportunities to show their talents in Saudi Arabia, particularly if they live in compounds. Sporting facilities in guest workers’ accommodations in places like Jubail, Yanbu and Dhahran are excellent. The full range of sports are catered for—playing fields (usually with a fine gravel surface), running tracks, tennis, squash and racquetball courts, swimming pools and gymnasiums.

Uniquely Middle Eastern-style golf courses can also be found in the kingdom. One of the authors was a member of the Whispering Sands club (logo: a camel with a golf club clenched between its teeth). This layout was constructed by an earthmoving contractor who turned an otherwise unused desert area into an 18-hole golf course. Facilities at the club were exceptionally basic. Greens were areas of the desert smeared with a bitumen solution. Tees were raised areas equipped with driving mats. Fairways were sand dunes that had been levelled. The rough was sand dune country left pristine.

Course architecture of this type has advantages and disadvantages from a player’s point of view. The courses play long and, under the hot desert sun, arduously. An essential piece of equipment carried by golfers playing the sand belt courses of Saudi Arabia is a square piece of AstroTurf off which the ball is played wherever it lands. The principal advantage is that playing every shot on AstroTurf certainly improves the lies. One of the curiosities in playing golf in the sand pits of Saudi Arabia is that there are no bunker shots!

Not all golf courses in the Middle East are quite like the Whispering Sands. Championship courses, of which there are a few, particularly in the UAE, offer completely irrigated grass layouts of a standard you would find anywhere. Saudi Arabia has one—the Riyadh Golf Club.

Waters of both the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea are suitable for swimming—though on the Gulf side of the country, the beaches tend to shoal very gradually. Despite the volume of oil being extracted and shipped, waters and beaches on both sides of the country are reasonably clean. Beaches are segregated into family beaches and men-only beaches. No women-only beaches are known to exist. Single men must not use family beaches. Women can only use family beaches. Both sexes should take care to establish the status of the beach they are intending to use.

Water sports other than swimming are also available. The Red Sea coast has a number of good dive sites where diving can be conducted hassle-free from the auhorities. Dive boats are available for hire. According to government websites, nautical activities such as sailing, windsurfing and waterskiing are permitted. But in the authors’ experience, what is actually allowed may depend on the rules of the day as interpreted by local authorities. One of the concerns the authorities have about people messing about in boats is the opportunity for espionage.

The moral aspect, too, must be borne in mind. An enterprising Dutch guest worker at a job site in Jubail once started an off-the-beach yacht club at a secluded beach. After a few successful meets, the club attracted a visit from the Mutawa’een. The objection of the religious police was not that the sailing club represented a threat to national security, but more that the Dutch girls on the beach and in the boats were, in their view, indecently clad. The club was raided, disassembled and closed down. By contrast, other sailing clubs, on both coasts, have remained open for many years. What gets shut down and what remains open is at the whim of individuals of the Saudi regulatory authorities responsible for community virtue.