‘An intelligent deaf-mute is better than an ignorant person who can speak.’

—Arab Proverb

Arabic, a Semitic language related to Hebrew and Aramaic, is spoken by over 180 million people in North Africa, and most of the Middle East as their first language. As the language of the Qur’an it is studied by many millions more Muslims globally.

Arabic is thought by some Westerners to be a difficult language because it is written in an unfamiliar script and some of the sounds are made at the back of the mouth and throat (the glottals). But it has its redeeming features. For instance, it is a stress/timed language making its rhythm predictable and regular, whereas English reduces and blends sounds together to fit its stress patterns. Intonation patterns of English and Arabic are similar: for example, questions are posed with a rising intonation.

The earliest copies of the Qur’an were written in a heavy monumental script known as Kufic but around AD 1000 this was replaced by Naskhi, a lighter cursive script joining letters together and widely used in Saudi Arabia today. Modern Arabic is not all that unlike other written languages. It has an alphabet and rules of grammar. The Arabic alphabet probably came into existence in the 4th century AD; it has 28 letters—22 consonants and six vowels. There are eight vowel sounds, including dipthongs, compared to 22 in English.

|

like the vowel in the word hat |

|

like the vowel in the word hit |

|

like the vowel in the word put |

The short vowels are not written because they occur in predictable patterns, although encoding words into script when script is being translated from English into Arabic can cause confusion, especially when your name is being translated into Arabic.

The five long vowels are:

|

as the vowel in father |

|

like the vowel in keen |

|

like the vowel in food |

|

like the vowel in home except the lips are rounder and tenser |

|

like the vowel in may but with the lips more tensely spread |

The consonants b, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, m, n, s, t, v, w, y and z are virtually identical to their English counterparts.

Pronunciation Guide

As nicely summed up by Lawrence of Arabia himself, transliteration of Arabic words is fraught with difficulties. Some letters in the Arabic alphabet do not have an equivalent in the English language. Here is a brief explanation of the pronunciation of the letters as they appear in transliterated text

Most of the 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet have similar sounds to those in English but Westerners often have difficulty in making some sounds. Some words like la meaning ‘no’ in Arabic require the speaker to make a sudden stoppage of breath at the conclusion of the word so that it sounds like ‘la-huh’. Other words like a’reed, meaning ‘I want’ in English, require the a to be pronounced as ah far back in the throat. The greeting phrase SabaHel Khair meaning ‘good morning’ requires the H to be pronounced similar to the h in English but far back in the throat. The Arabic word for the numeral five, khamseh, requires the kh to be a guttural sound like the Scottish ch in loch or the German ch in nacht. The metric weight gram is ghram in Arabic and the gh is as a guttural sound far back in the throat as the French pronounce the letter r in Parisian.

Arabic is read from right to left with the exception of the numbers which are read from left to right. Numbers in English are borrowed from the Arabic numeral system using one symbol each for 0 through to 9 and then adding new place values for tens, hundreds, thousands, and so on. A list of numbers in Arabic is found in the Glossary.

Arabic contains many references to God plus expressions of piety, courtesy and sociability. Bedouins infuse spoken Arabic with richness and emotion. The language has literary elegance, and a wide range of subtle meanings suit Arabic to poetry—a leisure activity of many Saudis. Formal poetry, prose and oratory play a key role in Saudi culture. Bedouin poets passed on their history to following generations, recounting in their poems ideals of manliness, gallantry, bravery, loyalty, generosity and independence of spirit.

Reflections of a Bedouin

Sandra Mackey in her book The Saudis recounts the story of an old Bedouin man suffering from a chronic disease who launched into a perfectly constructed poem after being examined by an American doctor at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital. In his poem, he praised Allah for being allowed to come to this famous hospital but, in verse after verse, lamented the fact that he was not yet cured.

Non-technical business communications within the kingdom are most likely to be in Arabic, with English communications fairly widespread. Technical subjects are mostly in English. With the advent of computers, the written aspects of business tend to be conducted in English, with perhaps an Arabic translation. Since Arabic is an alphabeticised language, it can be typed on a normal ‘qwerty’ style keyboard. Word processing software usually incorporates a switch facility on the standard keyboard so that bilingual typists can switch from one language to the other.

Legal contracts tend to be written in English, or maybe both languages. Somewhat oddly, if the contracts are drafted in English, then translated into Arabic, the laws of the land require that in the event of conflict between the English and Arabic version, Arabic prevails; thus preserving any translation errors that have been made in the final agreement!

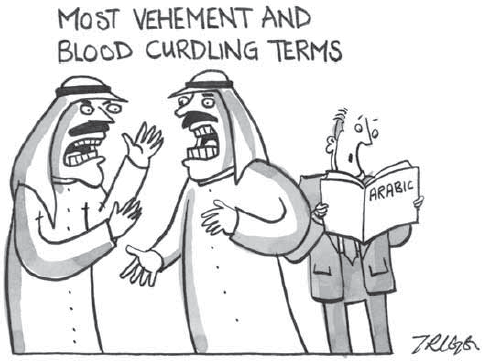

Saudis also use language, rather than physical fighting, as a means of aggression. When Saudis communicate in Arabic or English, they often do with exaggerated flattery. Threats are conveyed with a similar level of exaggeration. Through their love of language, Saudis are swayed more by words rather than ideas and more by ideas than facts.

As you go about your business, you will encounter shouting matches at incidents like motor vehicle collisions where the crowd of spectators become participants, waving their hands around and making a great deal of noise. In the parking lot like the one at the Safeway Supermarket in Damman, you may see a Saudi sitting in his car blocking someone else who wants to get his car out. The blocking Saudi will not move until he has completed his argument with the other driver, or until assembled spectators to the disagreement force him to move his car.

Despite such shouting matches, it is most unusual to see a Saudi strike another Saudi. This carries through to the government who, for example, regularly condemns the State of Israel in the most vehement and bloodcurdling terms but rarely takes action.

Saudi commoners expect their princes to use poetic language in announcements to other nations. Western commentators may have trouble decoding the real message behind the words. Take for example the simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’. To an American or another English-speaking Westerner, this is a definitive statement. Not so in the case of a Saudi. Because Saudis use flowery language and are accustomed to exaggeration and over-assertion, they find it difficult to respond to a brief simple statement. So when you hear a Saudi say ‘yes’ to a business proposition, you have to keep in mind that chances are he really means ‘maybe’.

Like most languages, Arabic has regional variations, but not enough to prevent citizens throughout the Arab world from understanding each other. Classical Arabic and Gulf Arabic are the two main variants that are spoken in Saudi Arabia although there are five major dialects.

Classical Arabic spoken in Egypt is generally held to be Arabic’s most prestigious form and is readily understood in most of the Middle East because of the massive export of popular Arab culture in the form of films, TV soaps and popular songs. Its grammar is more complex than dialect Arabic. Classical Arabic is usually spoken in formal discussions, speeches and news broadcasts, and is the only form of written Arabic.

Gulf Arabic is spoken by nationals in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Yemen, and is generally understood by Arabs living in Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Sudan and Syria. Gulf Arabic is less understood by Arabs living in North Africa and Iraq, although one of the authors had few problems when he spoke Gulf Arabic in Baghdad.

Arabic grammar is different from English grammar in quite a number of ways. In Arabic, verbs precede subjects. Adding laa or maa to a word makes it negative, rather in the same way as the English prefix un. Pronouns can be prefixed or suffixed to a verb which is always gender specific. Participles can be added to the beginning or end of words and can also be infixed or placed in the middle.

For those that are interested in learning it, Arabic is an interesting language. Those who make the effort to tackle the alphabet and acquire a basic vocabulary are likely to get more out of their visit to the Middle East than those that don’t. For anyone wanting to try learning Arabic, plenty of tutorial classes are available.

One point to note: those who take the trouble to learn Arabic will need to exercise their Arabic language skills judiciously. If you know enough Arabic to understand a conversation in the language, you ought to do one of two things: either keep your language skills to yourself or announce them at the earliest possible opportunity. Arabs will generally assume that non-Arab expatriates don’t speak a word of Arabic. Arabs are accustomed to speaking among themselves in front of Westerners, confident that they are having a private conversation that cannot be understood. If they subsequently learn this assumption hasn’t worked out, they may feel you have eavesdropped on their conversation.

The second language in Saudi Arabia, like most places is American English, which is taught in all schools and widely spoken throughout the kingdom. Signage around the countryside is in Arabic and English. In addition, English tends to be the second language of the guest workers from non-English speaking countries and over time, has crept into every day Saudi speech. For example Saudis are inclined to answer the telephone with a Saudi corruption of ‘hello-hallas’ and concluding their conversation with the Arabic word yella meaning ‘let’s go’ and then say in English ‘bye-bye’. English words that have crept into everyday Arabic speech include sandwich, bus and radio.

Saudi body language tends to be fairly forgiving. In fact, perhaps as you face your Saudi boss across the office desk and observe that under his desk, he has removed his sandals and is sitting on his foot placed on the seat of his chair, you may feel that in the area of bodily behaviour, anything goes. Like most places, Saudi Arabia does have a few prohibitions, though Saudis are not too pernickety in the unacceptable body language area.

But there are a few gestures that are considered insulting. Amongst these are the upward raising of a single finger, excessive pointing, fist clenching and clapping an open palm over a closed fist. One thing Saudis do not like to see is the soles of your feet. This is not a culture where you would put your feet up on your desk, or even use a footrest. Exposing the soles of the feet to another person is considered a mild insult. You should be careful how you arrange your limbs and try not to cross your legs.