In this chapter, we will focus our beginner’s concepts on two topics: (1) vectors and morphology and (2) the concept of fusion. Note that both are vector related. The rest of the information in this chapter is fairly easy to understand and follow. Vector analysis, however, is often glossed over in lectures and other intermediate books. Because of the strength of vector analysis in interpreting rhythm strips, we will not be making that mistake.

Vectors and Morphology

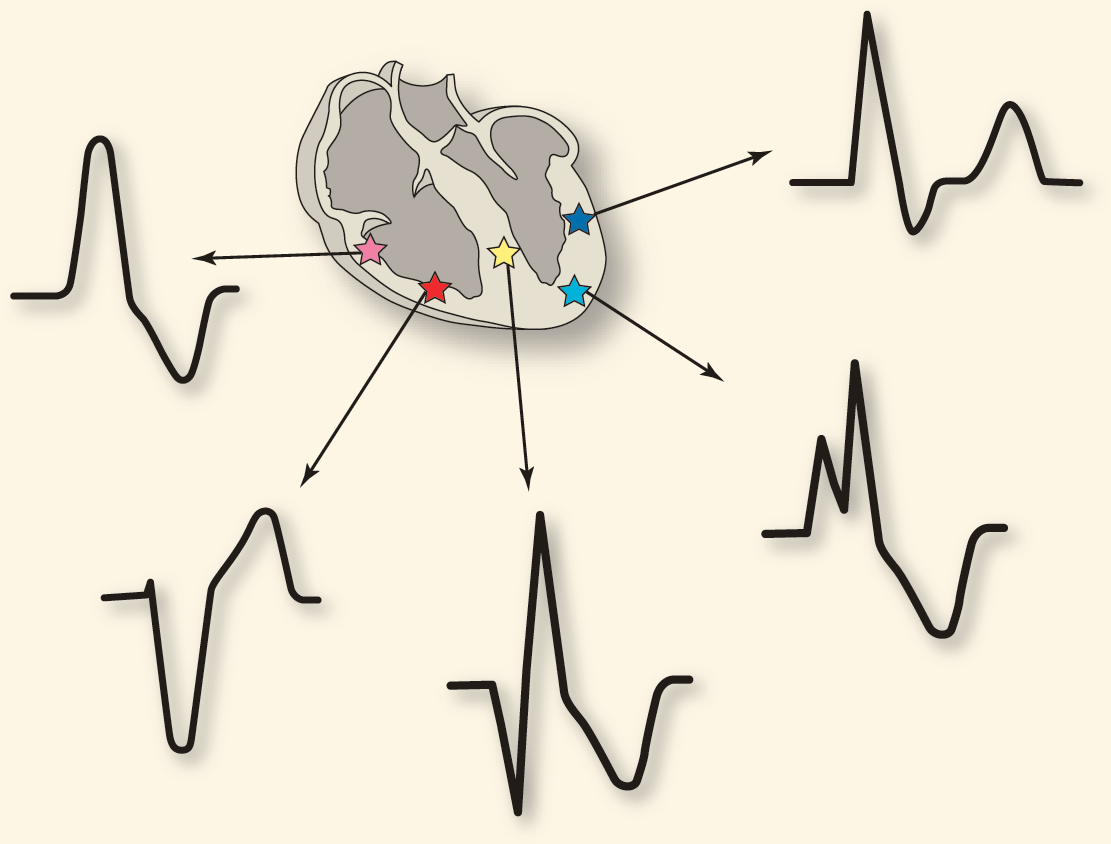

In Chapter 4, Vectors and the Basic Beat, we introduced the concept of vectors: they are the actual bioelectrical forces that are interpreted on the strip by the machine. We reviewed the appearance of sinus P waves and/or high atrial ectopic waves and saw how easily we could identify them based on their morphology and the direction of the deflection on the wave. In this chapter, we continue with this basic premise by using vectors to help identify their position. The key point to remember is that waves that are identical usually start in the same focus. Any variation in morphology means the point of origin is different or the route that the depolarization wave was forced to take was different.

Inset of Figure 6-19.

© Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Take a good solid look at Figure 6-19. This figure shows various ectopic ventricular foci and the morphologic expression of how the vectors travel to the rest of the myocardium from that one spot. Since most of those foci are in the myocardium itself, transmission does not occur through the regular conduction system. The result is that the wave is wide, representing the extra amount of time that the depolarization wave took on this slower cell-to-cell depolarization route. The morphology of the wave is also bizarre because it is not a synchronized wave but one that essentially moves from one side to the other. This lack of synchronization is a lot more than just an electrocardiographic aberrancy; it also means that the actual myocardium is contracting bizarrely. Instead of a nice squeezing action of the ventricles, the myocardium is contracting in ways that decrease or completely block the cardiac output by decreasing the amount of blood that is actually pushed out of the ventricles during systole.

Take-home point: Ectopic beats are not always benign.

Fusion Complexes

Fusion typically occurs when two impulses occur simultaneously. These two impulses cause conflicting graphical representations that reach the machine at the same time. The machine can’t print both, so it does its best to show a hybrid complex with characteristics of both impulses. This situation usually occurs when the two impulses are from different areas. An example is the P-on-T phenomenon. In this case, the P-wave morphology and contraction occur in the atria at the same time as the repolarization of the ventricles, represented by the T wave.

Fusion can be a strictly electrocardiographic hybrid or a mechanical one as well. This situation typically occurs when the waves actually cause mechanical contraction of the fibrils in the same area. In these cases, the resulting contractions can meet and cancel each other out mechanically. An example of this is when the normal transmission of an impulse occurs through the atrioventricular node and converges with an impulse from an ectopic focus in the distal myocardium that fired at the same time. These conflicting waves sum up both electrocardiographically and mechanically.

Take-home point: Always make sure you can identify what is going on in a fusion complex. It could be anywhere along the gradient from benign to life threatening. You need to figure out why and how it is occurring to avoid costly mistakes.

—Daniel J. Garcia