CESARE arrived back in Rome on 5 September, and spent the night in the monastery of his titular church, Santa Maria Nuova. The next day he rode to the Vatican to be solemnly received by the Pope. The formality of his reception by Alexander, who silently bestowed on him the ceremonial kiss, has been interpreted as indicating that the Pope knew that Cesare was responsible for Juan’s murder, and could not bring himself to speak to him. In fact his reception on the 6th was a purely ceremonial occasion; Cesare had already reported to his father the previous day.

Father and son must have had important matters to discuss. In the six hectic weeks which followed the discovery of Juan’s mutilated body in the Tiber, the Borgias had been obliged to rethink their entire dynastic scheme. Juan was dead. Jofre, not yet sixteen, was too young to play a part in either war or politics. Furthermore it was openly rumoured in Rome that he had not consummated his marriage with Sancia, while there were no doubts as to his elder brother’s virility, especially where Sancia was concerned. Clearly, hopes for the establishment of a Borgia dynasty rested with Cesare, but he was a cardinal, and as such was not permitted to marry. The Borgia solution to the dilemma was immediate and simple: if Cesare as a, cardinal could not marry, then he must renounce the cardinalate (an unheard-of step), and a wife and state must be found for him.

This project had clearly been discussed even before Cesare left for Naples; on 20 August Ascanio reported in cipher to Ludovico that there was talk of secularizing Cesare and marrying him to Sancia, while Jofre in compensation was to become a cardinal and to exchange his wife for Cesare’s benefices. By late September rumours of the Borgias’ new plans had reached Venice. Sanuto wrote: ‘It was rumoured throughout Rome that Cardinal Valencia, called Cesar, son of the pontiff, who had benefices of circa 35,000 ducats a year, and was the second richest cardinal in terms of revenues, how, desirous of exercising himself in warlike undertakings, wanted to renounce the cardinalate and his other benefices … The Pope would make him Captain of the Church.’ The Borgias looked to Naples to provide a wife and state for Cesare. The Aragonese dynasty was insecure, faced with internal dissension and the omnipresent external threat from France. In the circumstances it was not surprising that they thought that by turning the screws on the helpless Federigo they could obtain what they wanted in return for their support. They were after bigger game than Sancia, who was only an illegitimate daughter of the house of Aragon. Cesare and Alexander had fixed their eyes on the kingdom of Naples for Cesare, and marriage to Federigo’s legitimate daughter Carlotta as a necessary step towards the throne. A Neapolitan marriage for Lucrezia was designed to prepare the ground for Cesare, the first move in a Borgia takeover of the Kingdom. Before either of these projects could be realized, it was essential that Cesare should renounce his cardinal’s hat, and Lucrezia her husband, Giovanni Sforza.

Lucrezia’s divorce, and the Borgias’ obsessive pursuit of the matter, became something of a cause célèbre in the summer and autumn of 1497. Even in the tragic days following Gandia’s death, annulment had been in the forefront of their minds. At the consistory on 19 June, Alexander had announced his intention of starting proceedings on the basis of non-consummation, and had pursued the matter in his long conversation with Ascanio Sforza on the 21st, while Cesare separately told Ascanio that neither of them would rest until the divorce was concluded. The atmosphere surrounding the case rapidly became extremely unsavoury as the Borgias used Ascanio and Ludovico to put pressure on Giovanni Sforza to swear to his own impotence and thus gain an annulment on the grounds that he had been unable to consummate the marriage. When Giovanni, whose first wife died in childbirth, angrily denied the charge of impotence, his uncle Ludovico cynically suggested he should refute it by a public demonstration of his virility. The Ferrarese envoy quoted Giovanni as asserting ‘that he had known his wife an infinity of times, but that the Pope had taken her from him for no other purpose than to sleep with her himself. However, neither Ascanio nor Ludovico was prepared to sacrifice the Pope’s friendship for the sake of their expendable nephew, and was the second richest cardinal in terms of revenues, now, desirous was forced to give in. He signed a paper attesting to his non-consummation of the marriage which also obliged him to return Lucrezia’s dowry of 31,000 ducats. The divorce was officially promulgated in the Vatican on 20 December, but by the end of September the commission appointed by Alexander to examine the matter had already concluded that the marriage had never been consummated, and that Lucrezia was still a virgin. ‘A conclusion,’ wrote the Perugian chronicler Matarazzo, ‘that set all Italy laughing … it was common knowledge that she had been and was then the greatest whore there ever was in Rome.’

Lucrezia’s reputation was to come into question again within less than two months of the divorce, with the mysterious disappearance of one of the Pope’s favourite Spanish chamberlains, Pedro Calderon, known as Perotto. Early in February 1498 Cristoforo Poggio, agent of the Bentivoglio family, wrote from Rome to Mantua that Perotto had vanished, and was thought to be in prison, ‘for having got His Holiness’ daughter, Lucrezia, with child’. On 14 February Burchard noted dryly in his diary: ‘Perotto, who last Thursday, the 8th of this month, fell not of his own will into the Tiber, was fished up today in that river, concerning which affair there are many rumours running through Rome.’ Just nine months before, on 19 June 1497, Donato Aretino had reported: ‘Madonna Lucrezia has left the palace, where she was no longer welcome, and gone to a convent known as San Sisto … Some say she will turn nun, while others say many other things which one cannot entrust to a letter.’ Lucrezia’s exile to the chaste atmosphere of a convent may well have been caused by the discovery of her affair with Perotto, at the very time when her father and brother were anxious to establish her virginity for the purposes of her divorce. There were reports that Perotto’s body was found with that of one of Lucrezia’s women, Pantasilea, and his death was probably not only an act of vengeance but also the removal of evidence of Lucrezia’s misconduct at a time when negotiations for her remarriage were being carried on. Perotto’s death was later attributed to Cesare in the most melodramatic fashion, and it is not unlikely that he had a hand in it. Nothing would have been allowed to stand in the way of his plans for Lucrezia, which were so intimately allied with his own. In March 1498 an isolated report from the Ferrarese envoy to the Duke of Ferrara alleged that Lucrezia had given birth to a child, and the whole affair was complicated by the undoubted birth at the same time of the mysterious Giovanni Borgia, known as the ‘Infans Romanus’, whose paternity was first attributed to Cesare, but later in a secret bull of September 1502 admitted to be Alexander’s, possibly by Giulia Farnese. As with so many stories about the Borgias, the truth, concealed beneath a web of gossip, intrigue and deception, is impossible to discover.

Meanwhile, with the matter of his sister’s divorce successfully concluded, Cesare was energetically cooperating with his father in the plan for his secularization and marriage. On Christmas Eve Ascanio reported to Ludovico a long conversation he had had with the Pope on the subject, lasting four hours: ‘The principal content was briefly as follows: Cesare is working every day harder to put off the purple. The Pope is of the opinion that, if it does come to pass, it must do so with the least possible scandal, under the most decorous pretext possible.’ For Alexander and Cesare, however, the fabrication of a decorous pretext for putting off the purple was of less moment than ensuring that it would be worth his while to do so. He could not take the irrevocable step of renouncing his great ecclesiastical position and the 35,000 ducats in yearly revenue which it brought him, without being sure of a secular position with at least an equivalent income, and a wife to enable him to found a dynasty.

Somewhat to their surprise, the Borgias found King Federigo to be a major stumbling-block to their ambitions. Federigo, who knew both the Borgias well, recognized their takeover plan for what it was. Although he was prepared to sacrifice an illegitimate member of his house to the Borgia bull, and offered Sancia’s brother Alfonso, with the title of Duke of Bisceglie, as a second husband for Lucrezia, dynastic pride and political common sense made him obdurate in his refusal of his legitimate daughter for Cesare. Behind Federigo stood his powerful patron Ferdinand of Aragon, who had absolutely no intention of allowing the Borgias to annex the kingdom of Naples, which he meant to regain for the Aragonese crown. By mid-June the Venetian ambassador in Rome reported that there was no more talk of marriage between Cesare and Carlotta, since King Federigo had said publicly: ‘It seems to me that the Pope’s son, the Cardinal, is not in a condition for me to give him my daughter to wife, even if he is the son of the Pope,’ adding: ‘Make a cardinal who can marry and take off the hat, and then I will give him my daughter.’

As a sop to the Borgias, whom he bitterly described as ‘insatiable’, Federigo sent Alfonso to Rome to marry Lucrezia. His arrival on 15 July was supposed to be secret, but Ascanio wrote dryly to his brother that ‘the secret of the Duke’s presence here is known all over Rome’, noting that Cesare’s reception of his new brother-in-law was especially cordial and affectionate. Cesare had every reason to be kind to Alfonso, whose wedding to Lucrezia was generally regarded as a stepping-stone towards the greater object of his own marriage to Carlotta of Aragon.

Lucrezia herself was delighted with her new bridegroom, a handsome boy who charmed everyone who met him, and it was soon obvious that the young couple were genuinely in love. The wedding, celebrated in the Vatican on 21 July, was a family affair. The ambassadors, who were not invited, were naturally avid to pick up any titbits of information about the festivities which they could retail to their masters. As usual the Borgias did not disappoint them; the Mantuan envoy reported that an unseemly brawl between Cesare’s and Sancia’s servants marred the happy occasion. Swords were drawn in the presence of the Pope in the room outside the chapel where refreshments were to be served before the wedding breakfast, and two bishops exchanged fisticuffs. The scuffle caused such confusion that the servitors were unable to bring in the traditional sweetmeats and sugared almonds. When the turmoil eventually died down, the family party were able to sit down to a breakfast that lasted three hours until dusk. In the tableaux presented during the course of the feast, Cesare himself appeared in the strangely inapposite role of a Unicorn, the symbol of Chastity!

As he danced behind the horned mask at his sister’s wedding, Cesare’s thoughts must have turned optimistically to his own marriage projects. Despite King Federigo’s continuing obstinacy, the Borgias had found a new and powerful ally. In fact the summer of 1498 marked a dramatic reorientation of Borgia policy, as Alexander, in his search for a state and a wife for his son, turned away from his traditional friendship with Ferdinand of Aragon towards alliance with France. As spring passed into summer it had become increasingly apparent that Ferdinand represented the main obstacle to the plans for Cesare. Not only did he support Federigo, who was now entirely dependent upon him, in his obstinacy over the Neapolitan marriage, but he had expressed his strong opposition, and that of Isabella, to Cesare’s proposed renunciation of the cardinalate, and had adamantly refused to consider the Borgias’ demands that Gandia’s estates should be transferred to him to compensate for the loss of his ecclesiastical revenues. On 2 March Cristoforo Poggio reported: ‘I hear also that the Cardinal of Valencia will not put off the cloth, because he has not received the answer he wanted concerning the state of the late Duke of Gandia, which the King and Queen intend to go to his son, and as catholics are against such a deposition.’ Three weeks later he wrote that ‘the Most Reverend Valencia’ intended to pursue his plan to renounce that cardinalate, despite the opposition of the King and Queen of Spain and their refusal to grant him Gandia’s estates, since he was hoping to get what he wanted from Federigo.

The disparity between the two reports is indicative of the hesitations which Cesare felt at the prospect of crossing his personal Rubicon from the safe niche of the cardinalate to the uncertain shore of a secular future. Since the beginning of the year he had been seen more often in the practice of arms than in the exercise of his ecclesiastical duties. ‘Monsignor of Valencia every day exercises the practice of arms, and seems resolved to be a gallant soldier,’ Poggio wrote to Mantua on 19 January. His appearances in church were so rare as to cause Burchard to note with surprise on 21 April: ‘Cardinal Valentino attended the solemn mass in the papal chapel, he has not been seen since Passion Sunday.’ It was to be his last appearance: from then on he no longer attended ecclesiastical functions, nor wore the robes of a churchman. But at one point in the summer of 1498 the difficulties raised by Ferdinand and Federigo seem to have made him lose heart and wish to draw back. He was only driven on by the will of his forceful father. In June Ascanio wrote to Ludovico that Alexander was ‘every hour more ardent in his desire that this Valentino should change the habit; although Valentino does not want to, His Holiness has decided that he will do so …’

For the relentless Alexander had found a new avenue which he hoped would lead to a brilliant future for his son. Already in March, faced with Ferdinand’s antagonistic attitude, he had sent a friendly mission to Charles VIII of France. Charles made accommodating noises, but negotiations were interrupted by his sudden death at Amboise on 7 April 1498. Charles’ demise was a stroke of good fortune for Alexander: his successor, Louis XII, the former Duke of Orleans, had pressing domestic and external reasons for seeking the Pope’s friendship. First, he wanted to divorce his wife, Jeanne de France, in order to marry Charles’ widow, Anne of Brittany, so as to keep Brittany as an appanage of the French crown, and for this he urgently needed a dispensation from the Pope. Secondly, he had inherited not only the Angevin claims to Naples but also the Orleanist rights to Milan, and his assumption of both titles on his accession made it abundantly clear that he intended to assert them, in which case the Pope’s blessing on his enterprise would be essential to him.

Alexander was not slow to see the advantages which could be extracted from this new situation. As Machiavelli wrote: ‘The times served him well, since he found a king who, to separate himself from his old wife, promised and gave him more than any other.’ Although contemporaries like Machiavelli saw Alexander’s increasingly pro-French stance as motivated solely by his ambitions for Cesare, this was an oversimplification. Alexander was essentially a pragmatist, his policies always adapted to the realities of the Italian and international situation. By 1498 the League that had chased Charles VIII out of Italy lay in ruins. Within three months of Fornovo, in October 1495, Ludovico had hastened to make his separate peace with Charles at Vercelli, a typically turncoat reaction which did not endear him to his former allies. Venice, now violently anti-Milanese, was moving ever closer towards France; Naples, shattered and impoverished, was totally dependent on the arms and support of Spain; while Florence, debilitated and now hardly to be counted as a major power, was equally reliant on France for existence. It was clear to anyone as experienced in international politics as Alexander not only that another French invasion was imminent, but that from henceforward the physical presence in Italy of two foreign powers, France and Spain, was equally inevitable. For Alexander to oppose the French this time as he had in 1494 would have been unrealistic, to do so would have been to place the Papacy squarely in the arms of Ferdinand of Aragon. His aim was to increase the power and influence of the Papacy by playing the two powers off against each other, meanwhile extracting the greatest advantages for himself from either side. In 1498 it was obvious that there was nothing to be gained from Ferdinand, while an alliance with Louis offered a wide range of interesting possibilities.

In June Louis and Alexander exchanged missions. The French envoys were charged by their master to ask for dissolution of his marriage to Jeanne de France on the grounds of his having been constrained to it against his will by Louis XI, and that due to his wife’s deformity he had been unable to consummate it. In the last days of the month Alexander’s secret envoy, Francisco d’Almeida, Bishop of Ceuta, left Rome for France, where he arrived at court on 21 July. On 29 July, as a token of his goodwill, the Pope signed a rescript constituting the tribunal to examine the case for nullification of the King’s marriage. The outcome of d’Almeida’s mission is revealed in a document found in the archives at Pau, the text of a secret agreement under which Louis promised to support Cesare’s Neapolitan marriage project, and made several important undertakings in his favour:

1 The grant of the counties of Valence and Diois, the former to be raised to the rank of duchy, and the revenues of these estates to be made up to 20,000 gold francs.

2 The appointment of Cesare to the command of a corps of 100 lances fournies, to be maintained at the King’s expense at Cesare’s orders in Italy or elsewhere; this corps to be increased at the King’s option to 200 or 300 lances – an army of nearly 2000 heavy cavalry.

3 A personal subsidy to Cesare from the crown of 20,000 gold francs per annum.

4 Upon the conquest of Milan Cesare was to be invested with the feudal lordship of Asti.

5 Cesare would be invested with the collar of the Order of St Michael.

Cesare was to go to France, where Carlotta of Aragon was residing at the French court, for the marriage. To compensate the Pope for the loss of his presence, Louis promised to place at Alexander’s disposal in Rome a force of a thousand men, or alternatively 4000 ducats a month to pay for them, a proposal which indicated the extent to which Alexander already relied upon Cesare for security at Rome, especially in face of the renewed hostility from the Roman barons which manifested itself in July 1498.

This document is a significant illustration of Borgia aims and policy in the summer of 1498. Beyond the Neapolitan marriage and the provision of a high secular state and revenues for Cesare, he was to be launched on a career of military conquest in command of a significant body of troops. In return, Alexander tacitly abandoned Milan, Naples and his former friendship with Ferdinand, and held out to Louis the almost certain prospect of the dissolution of his marriage. In August d’Almeida returned to Rome with the news that Louis was sending an envoy, Monsieur de Trans, to Rome with the patents investing Cesare with Valence and Diois, and ships to escort him to France.

For Cesare, the die was cast. On Friday, 17 August 1498, he publicly announced his decision to put off the purple. Burchard reported:

There was a secret consistory, in which the Cardinal Valentino declared that from his early years he was always, with all his spirit, inclined to the secular condition; but that the Holy Father had wished absolutely that he should give himself to the ecclesiastical state, and he had not believed he should oppose his will. But since his mind and his desire and his inclination were still for the secular life, he besought His Holiness Our Lord, that he should condescend, with special clemency, to give him a dispensation, so that, having put off the robe and ecclesiastical dignity, he might be permitted to return to the secular estate and contract matrimony; and that he now prayed the most reverend lord cardinals to willingly give their consent to such a dispensation.

Cesare made his dramatic announcement to a half-empty house. Many of the cardinals, foreseeing an unpleasant confrontation with their consciences or their allegiances (the Spanish cardinals in particular), had absented themselves from Rome on the excuse of villeggiatura, the annual escape to the country from the heat and pestilence of the city. Relentlessly, Alexander rounded them up to give the stamp of their consent to this unprecedented step. He arranged for a further consistory to be held on 23 August, and, as the Venetian envoy reported, ‘wrote to all the cardinals who were in the neighbourhood of Rome, that they must come to the city, because matters were to be discussed touching the good of the Church and Christianity!’ Browbeaten thus by the Pope, the cardinals yielded. ‘The Pope,’ wrote the same envoy two days later, ‘with all the cardinals’ votes, has given licence that the Cardinal of Valencia, son of the Pope, could put off the hat and make himself a soldier and get himself a wife.’ The news caused scandal in Italy, France and Spain, but Cesare cared little for the world’s opinions. On the day of the consistory on the 17th, the French King’s envoy, de Trans, Baron de Villeneuve, arrived in Rome bearing the letters patent that would entitle the former Cardinal of Valencia to call himself duc de Valentinois. For Italians, the two foreign titles sounded almost the same; and ‘Valencia’ became ‘il Valentino’.

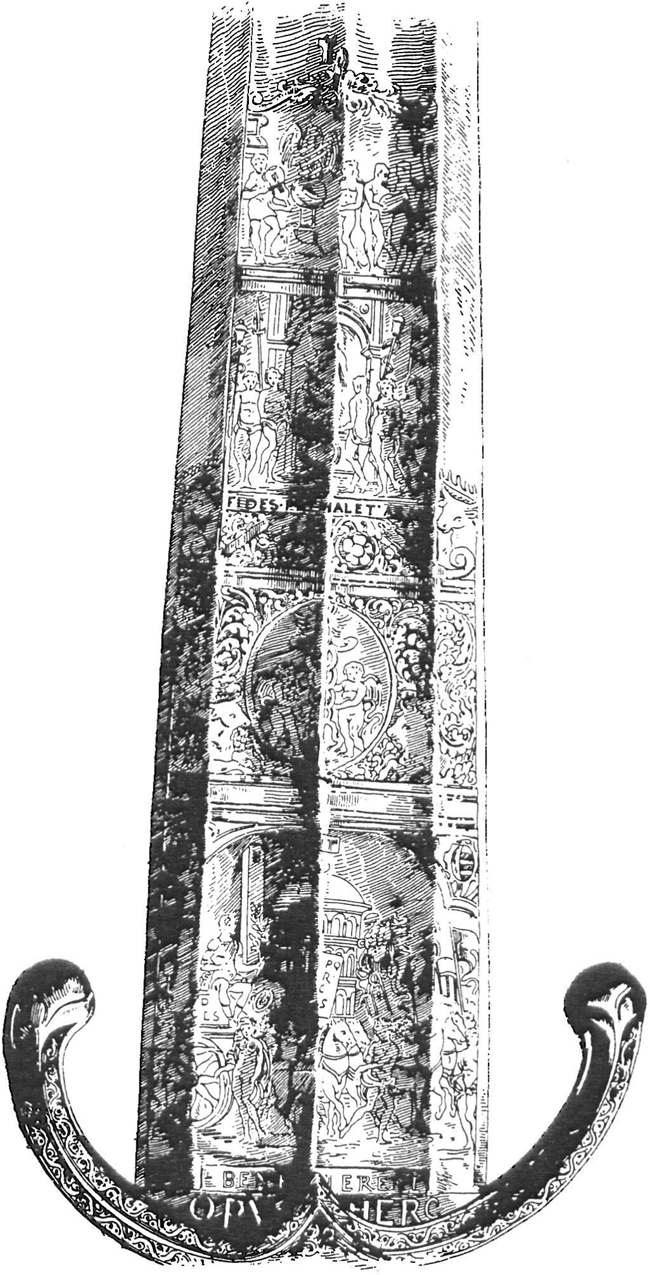

The parade sword made for Cesare Borgia in 1498

Cesare, at twenty-three, had crossed his Rubicon. His own consciousness of the importance of the step he was taking and its implications are embodied in the design of a magnificent parade sword made for him during the summer of 1498. The sword is decorated with Borgia emblems, bulls, and the downward-pointing rays, with the name CESAR arranged as a monogram, and its central theme is illustrated in six classical scenes engraved on the blade. The first represents the worship or sacrifice of a bull, standing on an altar inscribed ‘D.O.M. Hostia’ – Deo Optimo maximo hostia: ‘a sacrifice to the most high god’; underneath it runs the significant inscription: ‘Cum Numine Caesaris Omen’, ‘a favourable omen with Caesar’s divine good will’. The second shows Caesar crossing the Rubicon and inscribed beneath it his famous comment, ‘Jacta est Alea’, ‘the die is cast’. The third depicts the triumphs of Caesar, riding in a chariot inscribed D. Cesar (‘Divus Caesar’, ‘Divine Caesar’, which could also be a reference to Cesare’s own Spanish name and title, Don Cesar); beneath runs the motto ‘Benemerent’, to the well-deserving’. The other three vignettes represent Faith, the Roman Peace, and the worship of Love, frequently used as a symbol in Borgia decoration; while on the equally elaborate leather scabbard made for the sword (but never used) there is a scene representing the worship of Venus, who as a planet goddess was associated with the zodiac sign of Taurus, and thus with the Borgia emblem. Classical imagery as used in the Renaissance was never meaningless decoration; the scenes representing Caesar’s life were clearly of great personal significance to Cesare, symbolizing his own renunciation of the cardinalate and his hoped-for triumph in the secular world. For him, as for Caesar, arms would be the road to power. And with the motto ‘Cum Numine Caesaris Omen’, Cesare invoked his great namesake’s protection and help in his new career.

He now concentrated on preparing himself physically for his future as a man of action. His preparations included bullfighting on horseback, a Spanish sport which amazed contemporary Italians. Cattaneo reported on 18 August, the day after the consistory in which he had announced his decision to lay down the cardinalate: ‘In these days Valencia, armed as a janissary, with another fourteen men, gave many blows and proofs of strength in killing eight bulls in the presence of Don Alfonso, Donna Lucretia and “his Princess” [Sancia], in Monsignor Ascanio’s park where he had taken them remote from the crowd for greater privacy. In a few days’ time I hope to see him fully armed on the piazza.’ On at least one occasion, however, his physical exercises ended less gloriously; Cattaneo reported on 29 August that the previous evening Cesare had been practising in the gardens of the Pope’s vigna (the Belvedere in the Vatican garden) leaping astride horses and mules in one bound without touching the harness. He then ‘tried to leap in that manner onto a somewhat taller mule and when he was in the air, the mule took fright and gave him a couple of kicks in the ribs, one on the right shoulder, and the other on the back of his head. He was unconscious for more than half an hour.’

While this violent physical exercise was designed to keep his athletic body in trim, Cesare was seriously worried by his appearance. At this critical moment in his life, when he wished above all to impress the French court and a new bride with his splendid looks, the signs of secondary syphilis began to manifest themselves on his body, and, disastrously for him, on his face. Cattaneo remarked on his departure from Rome: ‘He is well enough in countenance at present, although he has his face blotched beneath the skin as is usual with the great pox.’ One can imagine the demoralizing shock suffered by a handsome young man of twenty-three at this inopportune reappearance of a disease of which he must have thought himself cured. Syphilis was a new phenomenon at that time, and relatively little was known about it; Cesare would not have known that the unsightly brown rash and dry skin which marked its secondary stage would clear up of itself within two or three months, and he must have been worried about its effect on his matrimonial prospects and his reception at court. The inner doubts and uncertainties which he felt at this testing moment in his life were outwardly revealed by his continuing to sign himself ‘Cardinal Valentinus’, as if he could not bring himself wholeheartedly to believe in his secular future. As Cattaneo wrote after his departure for France: ‘Valencia has certainly left in lay clothes, and having made his preparations as duke, nonetheless he signed himself up to the last moment as Cesar, Card. Valentino … and this perhaps as a precaution if things did not come out out as he wished or that perhaps, because of that face of his, spoiled by the French disease, his wife might refuse him.’

Cesare was well aware that if his crossing of the Rubicon could lead, as it had for Caesar, to fame and power, it could equally lead to ignominious failure. In turning their backs on the powerful King Ferdinand, and gambling on Louis for Cesare’s future, the Borgias were playing a dangerous game. ‘The King of Spain [is] extremely displeased with these ways of the Pope and Valencia,’ commented Cattaneo. ‘… However the Pope will disregard this, knowing that anyway there will be a rupture between them for this or for another cause.’ Alexander, he reported, said that he cared little for the children of the Duke of Gandia because they were more closely related to the King of Spain than to himself. This declaration of indifference to the children of his beloved Juan indicated the total abandonment of his Spanish dynastic policy and single-minded concentration of all his hopes upon Cesare’s future through France. Observers who were less daring and less involved than Alexander warned him of the dangers of his high game, not the least of which could be that Louis might use Cesare’s presence at court as a hostage to bend his father to his will. Cattaneo reported that when the Pope boasted to a great cardinal of Louis’ desire to have Cesare in his service, the cardinal replied:

It is true that Valencia is a dexterous man and has practised much in the exercise of arms, horses, and leaping, and uses his physical capacities to the full … but, believe me, Holy Father, that the King wants him because he doesn’t trust you, and Your Holiness is content in order to execute your own designs, but beware that you do not aim so high that, you or he falling, you will break too many bones …

But the Borgias were gamblers by nature; having weighed up the odds, they considered the prize worth the risk. No doubt Alexander, with his immense skill and experience in the game of high politics, thought that he would be able to handle Louis as easily as he had outmanoeuvred Charles.

Whatever the outcome might prove to be, Alexander and Cesare were determined to astound the French court with the splendour of the Papacy and the family. In an anxious desire to impress, Cesare spent wildly in the months before his departure from Rome. Two hundred thousand ducats had been raised for his expenses, partly from the confiscated goods of Pedro de Aranda, Bishop of Calahorra, who had lately been condemned for heresy, and partly, it was said, from the possessions of three hundred Jews. The money was spent on buying rich stuffs, Jewels, gold and silverware to such an extent that the Mantuan envoy reported that Roman supplies were exhausted, and additional luxuries had to be imported from Venice and elsewhere. Cesare wrote to Francesco Gonzaga, asking him to send him horses from his famous stud – ‘We find ourselves absolutely destitute of fine coursers suitable to us in such a journey’ – and a few days later to Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, requesting ‘a courser not unworthy of French esteem’, following it up with a demand for musicians. He went to the extremes of extravagance in his determination to bedazzle the French; the Gonzaga coursers were to be shod with silver, while Cattaneo reported that he took with him a most princely travelling privy ‘covered with gold brocade without and scarlet within, with silver vessels within the silver urinals …’

Thus magnificently equipped, Cesare took formal leave of his father on 1 October, and received from him letters of recommendation to Louis filled with expressions of the most extravagant paternal love: ‘We send Your Majesty our heart, that is to say our beloved son, Duke Valentino, who to us is the dearest of all …’ Alexander remained at a window of the Vatican watching Cesare until he was out of sight. Burchard, who continued to refer to him as ‘Cardinalis Valentinus’, wrote that he departed ‘secretly and without pomp’. This was true only in the sense that there was no official procession. Cesare’s progress from the Vatican to the Banchi, where he was to embark for Ostia, must have caused a considerable stir. He was dressed in a white brocade tunic, with a mantle of black velvet thrown over his shoulders (the first reported instance of his penchant for dressing in black velvet), a matching cap blazing with large rubies, and boots sewn with gold chains and pearls. Even his bay horse was draped in red silk and gold brocade, the colours of the royal house of France to which Cesare now belonged as Duke of Valentinois, while its shoes and harness were of silver. He was accompanied by Gaspare Torella, his personal physician, his confidential secretary Agapito Geraldini da Amelia, and the Spanish master of his household, Ramiro. de Lorqua, later notorious as the ferocious governor of the Romagna, plus a hundred pages, squires and grooms in crimson velvet halved with yellow silk, twelve baggage carts, fifty baggage mules, and a string of gianette, Spanish riding horses; the heavier chargers, corsieri had silver harness with silver bells – shades of Gandia – tinkling at their necks. A large suite of Spanish and Roman noblemen embarked with him: the Spaniards were soberly dressed in their national style; the thirty Romans, who included Giangiordano Orsini, son of Virginio, were as flamboyant as their leader in cloth of silver and gold, and had spent a thousand ducats apiece on their wardrobes for the expedition.

While Burchard, used to Italian ways, could describe Cesare’s departure as ‘without pomp’, the ostentation of his dress and equipment was to disgust the French court, accustomed to plainer northern customs. In Renaissance Italy the magnificence of a person’s outward appearance was considered an essential manifestation of his standing and importance. Cesare, though half-Spanish, was Italian enough to regard far bella figura, ‘cutting a fine figure’, as of prime importance. But it may be too that his over-ostentation betrayed an inner lack of self-confidence. Later, at the height of his power, he dressed in plain black velvet. The peacock splendour of his attire belongs to this early, uncertain phase of his career. And there was a physical reason for his flashy appearance at this time – the desire to enhance his superb athletic body to distract attention from his diseased face, natural in a young man bitterly conscious that his beauty had been marred, and who had not yet found success to bolster his self-esteem. Torn between the high ambitions expressed on his magnificent sword, and the doubts and uncertainties concealed beneath his splendid clothes and self-confident bearing, Cesare launched himself on his new career, embarking symbolically in a French ship.

His potential as a man to be watched, as distinct from his father the Pope, was now beginning to be recognized by observers at the Roman court. ‘All the principal fortresses are at Valencia’s disposal by the Pope’s will,’ the Mantuan envoy wrote ominously on 3 October. ‘Above all the castellans are Valencia’s men rather than the Pope’s …’ The wary envoys who haunted the Vatican antechambers, political reporters avid for significant news, were becoming aware of the nature of the Borgias, father and son, and of the scale of their ambitions. The significance of Cesare’s departure upon a French ship, destined for a military career, was not lost upon them. As Cattaneo wrote with wry foreboding on the day Cesare left Rome: ‘The ruin of Italy is confirmed … given the plans which father and son have made: but many believe the Holy Spirit has no part in them …’