1

URBAN ECOSYSTEMS

Just as oceans and forests and prairies are natural systems, cities and suburbs are also natural. While oceans have had hundreds of millions of years to evolve a network of interacting organisms, humans are relatively new to the planet. Cities are even more recent, the oldest having developed only about 5,000 years ago. We city inhabitants are animals who affect our surroundings in a natural manner, like any other creature. Other species have transformed the parts of the world in which they lived, but we have made by far the greatest impact.

When plants first moved from water and colonized the land, when the first vertebrates moved out of water and inhabited terrestrial environments, and when vertebrates evolved the capacity to lay shelled eggs on land, each innovation caused a major, irreversible revolution that transformed the world. The most recent transformation has resulted from the rapid growth of cities and suburbs, with entire regions greatly affected by humans.

Urban ecosystems are still in an early stage of development. For years our cities have been, and still are, built with only human needs in mind. Yet everywhere we go, we bring a similar set of variables, create a similar environment, plant the same trees, attract the same insects and rodents, and have many of the same birds. We take much of this for granted, without realizing that many of the species that live with us have not always been here. Starlings and house sparrows, for example, are abundant in every city in America, but they have been on this continent for only about 100 years.

New species continually move in, gain a foothold, and add to the diversity and complexity of the urban landscape. It is too early to predict with certainty which species will eventually adapt to, and thrive in, these new settings, but educated projections can be made. Opportunities exist for certain species in urban environments that do not exist in rural environments. Cities offer food sources, places to live, wide open spaces, species to parasitize, species to prey upon, trees to nest in, buildings to roost on, warm evening skies to catch insects in, warm polluted waters to seek refuge in, rich effluents that support aquatic ecosystems, underground sewers to breed in, and cavernous subway tunnels and hundreds of thousands of miles of pipes to move about in.

Cities have their own variables: buildings, pavement, scattered green areas, street trees, gardens, and house plants. These affect the ecosystem, as do the thousands of people who walk in the parks and compact the soil, making it difficult for rains to be absorbed, creating problems with runoff and erosion. Nutrients that flow into low areas and collect in city ponds feed the plankton and the algae so the water clarity decreases and blocks out sunlight. The plants die, fall to the bottom, and rot. The bacteria, while consuming the dead plants, also consume the oxygen, creating a deficit that is difficult for gill-breathing animals to tolerate. As a result, city ponds are generally inhabited only by species adapted to living in such an extreme environment. These aquatic ecosystems may exhibit less species diversity, that is, contain fewer numbers of species, than similar areas found outside the cities, but that’s because it takes years for those species that can live in these new, isolated, metropolitan islands to arrive and become established. More often than not, they are brought here, sometimes unintentionally.

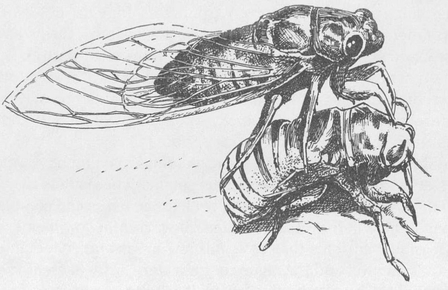

When natural areas are cleared to establish an urban landscape, most of the woodland, grassland, or desert species that once lived there will be unable to adapt to the changed environment. They must leave or die. Only a few remain and survive. One survivor may be the cicada. Years after a city has been built up in what was once a woodland, we still find cicadas each summer. These cicadas are probably descendants of populations that lived there before the city was built. Their numbers may have diminished, but in some urban parks you’d never know it. In other parks, however, where the trees have been cut and the ground has been paved, the cicadas haven’t had a chance.

Many populations of species continue to survive in cities after their natural environment has been radically altered. Some may even benefit from the changes because of reduced competition from other species. Painted turtles and snapping turtles survive in many freshwater environments, sometimes even in brackish water, after other turtles are long gone. Pumpkinseeds and bluegills—two species of freshwater fish—actually experience population explosions after their habitat becomes urbanized. Some pioneer tree species, those that move into open areas, thrive in vacant lots after an area has been cleared. They would have been significantly less numerous if the city had not been built because they do poorly among stands of mature trees. And many species of roadside plants, which never had roadsides to grow along before the people moved in, experience windfall increases in new places to live. Many of these plants thrive on alkaline soils, which are relatively scarce in the wild, while some are among the more successful species in cities because of the lime that leaches from the concrete, affecting the surrounding soil.

Cicada on empty nymphal sac

Other opportunities exist for species that can move in from surrounding areas and exploit the changed environment. For instance, chimney swifts and barn swallows, which nest in hollow trees, will sometimes nest in man-made structures instead. Because there are many more buildings than there ever were hollow trees, these species may actually increase in numbers as an area becomes more urban.

The changed microclimate of cities also affects plants and animals. Most cities are warmer than the surrounding regions because tar, concrete, and stone absorb heat and then slowly radiate that heat when the temperature drops. This allows some species to flower earlier, lay their eggs earlier, or store more food during the summer, changes so significant that some will do markedly better in cities than in the country. Other species will extend their ranges, moving from one city to another.

During recent years several southern birds and mammals, such as armadillos, opossums, mockingbirds, and cardinals, have been extending their ranges north in this way. The reasons aren’t always clear, but the range extensions are well documented. Other species moved from the Great Plains into regions where forests have been logged. These include loggerhead shrikes, brown-headed cowbirds, cliff swallows, and dickcissels.

Some species accompany people wherever they go, arriving in a region once it has been greatly affected by humans. People bring along their pets such as dogs and cats, while many other species are brought along inadvertently, such as the book lice that live in old books and the silverfish and roaches that live in human dwellings. And of course rats and mice live in just about every city. Other species that commonly accompany people are the beetles that live in our stored grain, and the plants that have escaped from our gardens. Some insects from other countries come in on fruits and vegetables. Worms, centipedes, and millipedes may arrive in imported flowerpots. New species are constantly arriving; occasionally an alien becomes established in its new environment.

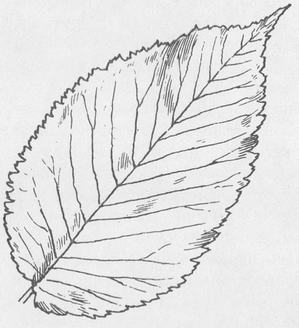

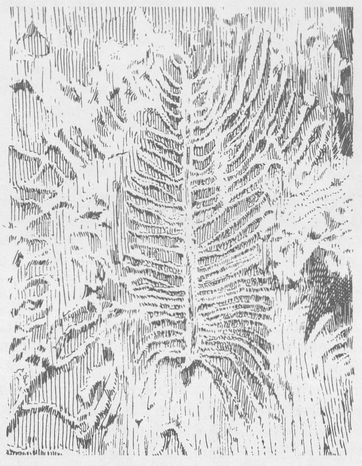

Some of these new species are seldom noticed; others become a tremendous problem. If a species has few competitors and predators, its numbers may increase dangerously. Or a plant disease may run rampant in a new area. For example, a disease that attacks chestnut trees did little damage in Europe where the trees had built up a resistance. When the disease traveled to the United States where the trees had no resistance, most of our chestnuts were dead in a matter of decades. A disease that attacks elms also managed to hop a ride to North America. It infected American elms, a favorite urban tree, and we lost hundreds of thousands of beautiful, mature trees.

American elm

Pattern left from hatched-out elm bark beetle larvae, from under the bark

If a crate of parakeets breaks when being unloaded at an airport, all the birds may fly off, soon to become established in the surrounding region. Or rabbits from the West may escape and settle in the East. Fish may be released and survive in local waters. These things tend to happen with greater frequency in places where many people live; as a result, new species are introduced into urban areas all the time. Over the years, many of the same species repeatedly colonize other cities; thus urban ecosystems around the world slowly increase in complexity while their floras and faunas survive and even flourish.

In recent years, some cities and countries have begun to try to reverse the degradation of the urban environment. People are trying to clean the air and the water, create parks and improve those already in place, plant trees, and maintain green patches. It is possible to utilize natural processes and ecological principles to revitalize degraded habitats. Intervention can take the form of attracting, introducing, or reintroducing specific species that can add to the quality of an urban environment. More effort needs to be expended to make our cities more livable, for us as well as for other organisms. One way or another, species are going to move in and live by our sides. We can make it easier for them to survive and flourish, and in doing so, we will create a better environment for ourselves.