2

GRASSES AND WILDFLOWERS

Plants include fungi, algae, grasses, sedges, rushes, forbs, vines, shrubs, and trees. Since a full discussion of all plant forms that appear in cities would fill several volumes, I will deal only with those species of grasses, wildflowers, and trees that are very well represented in U.S. cities. In this chapter I’ll discuss the most frequently seen urban grasses first, then talk about some important wildflowers in more detail. Trees are the subject of Chapter 3.

GRASSES

Of the 250,000 species of plants, over 10,000 are grasses. They include many of the economically most important plants. Species such as barley (Hordeum vulgare), bamboo (Bambusa spp., Dendrocalamus spp., and allied genera), corn (Zea mays), millet (Setaria italica), oats (Avena sativa), rice (Oryza sativa), rye (Secale cereale), sorghum (Sorghum vulgare ), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), and wheat (Triticum spp.) are some of the most useful plants in the world. Once some 42 percent of the land area of the earth used to be grasses, that has now declined to about 25 percent. Grasses grow well in rich soils, but many species will thrive in less favorable locations. Some, in fact, flourish along roadsides or grow in the cracks in sidewalks and in other urban places where nothing else will grow.

Most of the prairie in much of the Midwest was once covered with grasses, legumes (plants in the pea family, Leguminosae), and forbs (flowering plants that aren’t grasses, aren’t grasslike, and aren’t woody). In the East, the colonists cleared the forests and planted English grasses to feed their cattle, species such as timothy (Phleum pratense), a coarse grass with cylindrical spikes; Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis); and fescue (Festuca spp.). These grasses still grow in cultivated hay meadows, but are a diminishing part of our landscape. When the settlers moved farther west, clearing the forest as they went, western prairie grasses and other associated species moved east, taking advantage of the new open habitat. In the East, where many of the meadows have been left unmowed and where no cattle graze, the species composition seems to favor, along with many of the wildflowers, some of the coarser grasses, such as the little bluestem (Andropogon scoparius). The next step for these old fields would be the invasion of woody plants, but this can be averted by having controlled burns. The dried grass readily burns off, hardly singeing the soil, leaving the extensive root systems unharmed. The bark of the woody species burns, destroying the cambium layer or exposing it to insects and pathogens that kill the trees, allowing the grasses to grow back even more vigorously afterward.

In suburban areas, by far the most widespread grassland is the lawn. Left alone, lawns would become meadows, but social pressure keeps them carefully manicured. The social mores are sufficiently powerful to stimulate homeowners to spend more time, energy, and expense maintaining their lawns than it takes to maintain equal areas of corn or tobacco. The total acreage of American lawns amounts to 20 million acres, almost 2 percent of the entire country. In each part of the country these weed-free lawns usually harbor at least another 30 species of plants and 100 species of insects. As many as 10 to 15 species of birds often inhabit these communities, as well as several associated species of mammals. The importance of these habitats should not be underestimated.

Another grassland found near many coastal urban areas is the salt marsh. Only about one-half of America’s original salt marshes survive. The others have been filled in and used for other purposes. However, the existing marshes are now recognized for their major ecological contributions, and many of them are protected by law. Of course, developers will often try to circumvent the laws, but with the recent proliferation of grass-roots environmental organizations, it usually takes a considerable fight to overtly destroy a salt marsh today. Many developers have learned that the occasional victory is rarely worth the expense and bad publicity.

The lush green salt marshes are flooded twice each day with the incoming tides. The salt-tolerant species of cordgrass in the genus Spartina tend to dominate these habitats.

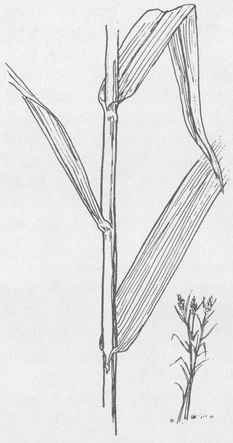

Another well-known grass is Phragmites, the common reed, which is often found along the drier edges of the salt marshes. Until recently called Phragmites communis but now called Phragmites australis, this species is found around the world, in temperate climates. It grows in a wide range of habitats and is very much on the increase in urban environments. These reeds create a thick, tall mass of growth along the edges of marshes, especially those that have been disturbed. They often reach 6 to 9 feet (2 to 3 m) in height, creating a dense barrier that looks like a fence, which is what the Greek word phragma means.

Phragmites

Because this plant rapidly invades disturbed areas, doing especially well in low, wet regions, it finds many opportunities for growth in cities and suburbs, where the land is often disturbed. Phragmites moves in and outcompetes the other vegetation, creating what appears to be a monoculture, or a stand of just one species. Actually if you walk through a stand of Phragmites and carefully evaluate its value in terms of other species living there, you will find that the Phragmites may radically alter a habitat once it has moved in, but it doesn’t totally destroy the habitat. And in cities, where disturbed areas are often replaced by meadows of Phragmites, the beauty is unassailable. The cover for birds and other species is also valuable, and these meadows are better than no meadows. This species is not everyone’s favorite. Some people consider Phragmites opportunistic, aggressive, invasive, and impossible to get rid of. But the grass is to be commended for its ability to move in and take advantage of the damage humans leave in their wake. If we don’t want Phragmites, we should treat the soil with more care.

Once the land is disturbed, it’s usually only a matter of time before Phragmites moves in to fill the void. Its large, feathery tops contain small, umbrellalike seeds that fill the air in the fall. Most people never notice the seeds, but on a good and windy day they are absolutely everywhere, millions blowing in from nearby Phragmites meadows, which may be miles away. Those that land on the water wash to shore where they germinate; those that land on suitable soil grow and in time make their presence known.

Some of the more remote, wild urban parks have large stands of Phragmites, and fires are common among the dead, dry standing canes. Most of these fires are thought to be a result of arson. Like it or not, arsonists may be as hard to control as Phragmites, so the frequent burns in urban stands of Phragmites might as well be viewed as a natural part of the ecosystem. Some of the fires can be traced to lightning; the dead vegetation seems to lend itself to ignition, as if waiting for lightning to strike. Some researchers have even suggested that the dead material may be capable of self-ignition, but that has never been shown. At any rate, these fires appear to be beneficial, as evidenced by the rapid increase in biomass (weight of living material, usually expressed as dry weight per unit area) after a fire. The fires seem to burn off the old, dead biomass, creating new hollows in the old wetlands and rejuvenating the habitat for the Phragmites and other wetland-dwelling species. Without such fires, the rapid buildup of dead canes would fill in the low areas, creating higher, drier ground where Phragmites would eventually be replaced by highland vegetation. So the fires tend to preserve the Phragmites populations.

Few people bother, but much of the Phragmites plant is fine to eat. Before trying it, be sure you have the right species. Look for the key characteristic—plumelike flower and, later, the puff of seeds at the top of the plant. The flower has a light purplish hue and is quite attractive. Another identifying feature is its extreme height: few grasses in North America get as tall as this species. The young shoots can be boiled, just like asparagus. They may be eaten warm, cooled, and served as a salad, or even pickled. Also, the young green stems can be taken while still fleshy. After they have been dried out, they can be pounded into a flour. Add water to this powder to form a dough. You can roast a wad of dough like a marshmallow, and it is quite good. The rhizome—the thick, horizontal, fleshy root—can be boiled and eaten like a potato. And the seeds can be ground into a flour, then mixed with water or milk and boiled to make a gruel.

Another grass that is easy to identify is one that grows along the shore in sandy areas. Known as beach grass, Ammophila breviligulata can survive drought, fire, and frequent burial by shifting sands. It can also tolerate being flooded with saltwater during storms. This grass holds the sand down with its roots, and the leaves and stems catch blowing sand and help build dunes. Where people and off-road vehicles are allowed to trample the beach grass, it may well be that the dunes will blow away.

You will find several other common species of grasses along the streets and sidewalks in urban and suburban areas. Few people ever learn to identify these plants, even though most are relatively easy to recognize. Part of the problem is that no adequate field guide has been available. Another part of the problem is that grasses do not have characteristics that attract people’s attention. They do have flowers, but they rarely develop showy blossoms because they take advantage of the wind for pollination. This means that they don’t have to attract insects with large, bright petals that would advertise the sugary nectar that they don’t have, since the wind works for free, without being lured by sweet, colorful incentives.

One of the more common roadside grasses is crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis), a worldwide species that is quite familiar. It grows in lawns, usually in patches where nothing else grows. It is also seen among the weeds along sidewalks or under street trees. Crabgrass, which was introduced from Europe, does very well in lawns because its seeds are set very close to the ground, so lawnmowers are ineffective at controlling its growth. Keep in mind that crabgrass does very poorly in the shade. You can partially control it by allowing your grass to grow a little higher than usual until it shades the crabgrass out. Some weed-killers sold over-the-counter will kill crabgrass, but who knows what damage these products will do to other organisms?

Another roadside plant is yellow foxtail grass (Setaria viridis), which is widespread as a weed throughout North America. Sometimes called wild millet, this grass is in the same genus as millet and looks quite similar, though the seed heads are considerably smaller. All of the seeds, which are clustered at the end of the stems, have yellowish brown bristles; they look like a yellowish foxtail—thus the other common name.

Other common grass species include perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne ), goose grass (Eleusine indica), panic grass (Panicum clandestinum), switch grass (Panicum virgatum), barnyard grass (Echinochloa crus-galli), early chess (Bromus tectorum), and orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata). After you have learned these, you will find it easy to identify many other species. From there you can move on to rushes and sedges, which are grasslike herbs.

In addition to the numerous grasses that grow in urban and suburban areas, many species of wildflowers can be found growing in parks and woodlots, in empty lots, and along roadsides. A few urban wildflowers are valuable for their showy beauty. Many others have less spectacular blossoms, but are useful in some other way. And many others are just there, useful or not. In any case, they’re all interesting.

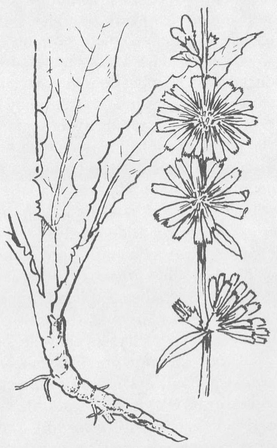

CHICORY

Chicory (Cichorium intybus) tends to grow among weeds along roadsides and in areas with poor, sandy, disturbed soils. This plant would probably do much better on rich soils, but it doesn’t always compete well with native species, and seed distribution may limit the places where it is found. It is amazingly widespread in this country, considering it isn’t native. It was brought over from Europe, where it has a history going back to the times of the ancient Greeks and Romans, who found many uses for it.

Chicory

Chicory can be easily identified during the summer by its light blue, dandelion-like blossoms on either side of a long, stiff stalk that usually reaches a height of about 3 feet (90 cm). A member of the daisy family, Compositae, its flowers differ from other daisies in that they are composites of many ray flowers—the flat, long flowers usually thought of as the petals—and, also unlike other daisies, it does not have a tight center cluster of small, tubelike disk flowers.

Although its flowers are very pretty, chicory is a poor choice for bouquets. The flowers don’t all open at the same time; the lower ones blossom before those higher up on the same stem. After each flower has opened, it will close while the seeds mature inside; these flowers aren’t particularly attractive. An added disadvantage is that the blossoming of the flowers is staggered from June right through October, so there is no single time when you can go out and pick a stalk with many beautiful flowers on it. In addition, the flowers don’t stay open all day. They tend to open very early in the morning on sunny days and somewhat later on cloudy days; most of the flowers are already shut by noon. This isn’t a feature peculiar to chicory alone; many flowers open for a short time during the day, or even during the night, and then shut. The cycle seems to depend on their pollinating insects. Flowers that are pollinated by moths, for example, often open during the night. They have flowers that reflect as much light as possible, so they therefore tend to be white; or they have a powerful fragrance to pull in the pollinators that might otherwise have trouble finding the flowers. It seems to be more efficient for chicory to open during the early hours of the day, get pollinated, and then shut. Even if the flowers were not pollinated, they will shut anyway, and then open again the next day, thereby protecting their delicate structures from the hottest, most destructive part of the day.

Unlike dandelions, chicory seeds do not have little parachutes that carry them aloft, acting as a distribution mechanism. This makes it all the more amazing that this species has become so widespread since its introduction to this country. The chicory plant was probably brought here for its edible parts. The leaves taste best during the early spring when they haven’t laid down the bitter chemicals that protect them against herbivorous insects. Again in the fall, after the weather gets cold, the raw leaves become quite mild and pleasant. In the spring, the toothed, elongated leaves, which are similar to those of the dandelion, grow in a tight circle, or rosette, close to the ground before the long stalk shoots up. No species with leaves like these are poisonous, so you shouldn’t feel that foraging for chicory can prove dangerous. In Europe, especially in France, people dig up the long taproots, which resemble those of the dandelion, and plant them indoors. They pick off the young leaves during the winter for use as a vegetable.

A relative of chicory is Cichorium endivia, the cultivated endive, which is in the same genus. This, too, is picked when the leaves are young and is eaten raw in salads. Many consider it a delicacy. Some people, however, dislike the bitter taste of chicory, endive, and dandelion greens. These close relatives contain a chemical that is agreeable to some palates and offensive to others.

The roots of the chicory plant also have some uses. You can clean the taproots and then bake them in a 300° F (149° C) oven until they turn dark brown, dry out, and become crunchy and fragrant. Then you can grind them up and use the grinds just like regular coffee. They may be used alone to make a pure chicory brew, or added to coffee for a fuller, richer flavor. Unlike coffee, chicory contains no caffeine. It is also free from the many chemicals found in decaffeinated coffee, leftover residues from the decaffeination process. Next time there’s a sharp rise in coffee prices, collect chicory roots. And if you need a reason to dig up the dandelions (Taraxacum officinale) in your yard, use their taproots, too. When prepared in the same manner, their flavor is similar to, though not quite as good as, chicory.

MUGWORT

There are about one hundred North American species in the genus Artemisia. Most are called mugwort, wormwood, or sage. Many of these were brought over from Europe where wormwood has been known and appreciated for years. In the United States, as an urban weed, mugwort has received little attention, but that does not mean it is insignificant. This is a major weed, and in many cities, it is to disturbed soils what goldenrod (Solidago spp.) is to old fields in the country. The major differences between mugwort and goldenrod are that mugwort isn’t native, it thrives on disturbed soils, and it doesn’t have a showy flower. Goldenrod, of course, has a lot of enemies because of the belief that its pollen causes hay fever. Actually, the pollen is quite harmless; it is the pollen of other, less conspicuous species, such as ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), that causes most allergy problems when the plants are blossoming in the late summer and fall.

Like ragweed, mugwort has inconspicuous flowers, which explains why it is not widely recognized. For the same reason, few people know the grasses, sedges, and rushes. People are more likely to notice showy flowers—the big pretties—and ignore the rest. Most observers don’t even have the vocabulary to describe many of these species, and some of the popular field guides don’t bother to include wildflowers having small greenish flowers.

Mugwort

Our urban mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) is a relative of the native sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), which is common throughout much of the arid West. Reaching heights of several feet (1 to 2 m), mugwort’s alternate leaves are deeply cut and jagged. Every leaf is different, and adjacent plants also often look considerably different. Unlike sagebrush, which has silvery leaves, mugwort’s leaves are usually dark green above and lighter, almost silvery, and slightly hairy beneath. The upper leaves usually sprout from the plant without much of a stem, while the lower leaves have longer petioles (the slender stems that support the leaves). Later on in the year, the tops of the branches develop heads of small, greenish yellow flowers that are either in rounded bunches or in spikelike heads. The flowers are disc-shaped, with a narrow base and a crown of tiny bristles at the tip. The stems are erect; the branches create a rather woody plant that stands during the entire winter.

A less common relative of mugwort that looks quite similar is the biennial wormwood (Artemisia biennis), another introduced species that does well in open, disturbed areas. Mugwort, however, has clusters of flowers toward the end of the stalk; biennial wormwood has leaves interspersed among the flowers, which are clustered next to the main stem.

The leaves of members of this genus have a powerful odor and a taste that is usually bitter and quite pungent. Some species that live in Israel are mentioned in the Bible. Solomon spoke to his son of “The lips of a strange woman as a honeycomb . . . but her end is as bitter as wormwood.” The desert wormwood (Artemisia herba-alba) is very common on dry soils around Jerusalem. Its odor is strong, distinctive, and actually rather pleasant. The Judean wormwood (Artemisia judaica) has very bitter leaves and stalks, but the smell is even more pleasant than that of the desert wormwood. When a small amount of wormwood sap is added to wine, the bitter taste creates a new flavor, and this mixture is referred to in the Talmud as vermouth wine, or the “bitter absinthium wine.”

Artemisia absinthium was used as a vermifuge, a medicine to kill intestinal worms, hence the name wormwood. Pieces of the dried plant were placed in cupboards to keep insects away. When tea made from the leaves is sprinkled on the ground during the spring and fall, it has been observed to reduce the number of slugs and beetles that might otherwise be there. Some of these uses were discovered in Europe hundreds of years ago, but they are just as valid today. Some people still crush the leaves and rub the juices on their clothes as an insect repellent. When you walk through a field of mugwort, you will notice that very few insect species live in it. This could be because the chemicals in the mugwort act as a natural repellent to many invertebrates, which may account for its bitter taste and odor. Or the fact that few species of insects live on mugwort could be because the plant tends to grow in urban areas where the insect fauna is generally sparse. Or, perhaps, in the short amount of time since mugwort was introduced to North America, very few native insects have had a chance to adapt to this peculiar plant.

Most stands of mugwort are rather uniform, composed primarily of this species. Other plants live among mugwort, but they are relatively insignificant in total ground cover. Because it competes so effectively against other species on dry, disturbed soils, mugwort is not popular with urban dwellers. This seems unfair, since mugwort is certainly preferable to many of the alternatives. It can even be mowed and kept short and neat. However, when kept short it looks ragged and uninteresting. But cutting a stand once a year, or once every other year, might allow other species to invade and compete effectively.

We do not completely understand why some plants thrive on disturbed soils when just a few miles out of town these species are virtually nonexistent. Factors such as the number of seeds, mode of seed dispersal, seed dormancy, time of germination, growth rates, energy allocated to reproductive effort, length of time from germination until flowering, mode of pollination, and when the plant sets its seeds may all be important. Species like mugwort, while phenomenally successful in the New York metropolitan area, are almost unknown upstate. Today mugwort is found primarily in the Northeast, but it is spreading and now grows in many cities of the West.

PLANTAIN

The plantain family (Plantaginaceae) does not contain the bananalike plantains. This is a family of small plants that have leaves crowded into a tight rosette, and small flowers, which are characteristically located on the end of a long, erect stalk. The genus Plantago comprises more than 200 species. Two of them are very common, occurring on disturbed sites, especially roadsides, lawns, ball fields, and similar habitats throughout much of Asia, Europe, and North America. Having been introduced to North America during colonial times, probably with grains used for planting, both the English plantain, or the narrow-leaved plantain (Plantago lanceolata), and the common plantain, or broad-leaved plantain (Plantago major), are now found throughout the United States and Canada. These low plants are usually only about 6 inches (15 cm) tall, but they sometimes reach a height of 1 to 2 feet (30 to 60 cm) in unmowed areas.

Plantain

The English plantain has narrow leaves containing three veins. When flowering, it sends out a long, grooved stalk with a bushy little flower head at the end. The common plantain has broad, more rounded leaves, all tightly clustered together near the ground. Its flowers blossom along much of the long, hairy stalk instead of in a tight cluster at the tip.

Plantain pollen has been found in archaeological digs at European sites dating from the Paleolithic period. This tells us that weeds moved in thousands of years ago when these areas were cleared for human habitation. Among those weeds were some of the same species still associated with human habitation, including plantain. It was noticed long ago that wherever people moved, plantain went with them. Native Americans noticed it when Europeans first came to America. The Indians, who had never seen Plantago major before the white men arrived, noticed that it grew only where Europeans had been, so they called the plant Englishman’s foot, or white man’s foot.

Throughout history, plantain has been used as a remedy for ailments. Shakespeare mentions it in Love’s Labour’s Lost: III. 1.71, where Costard says, “No salve, sir, but a plantain,” and in Romeo and Juliet: I. 2.51, when Benvolio has a broken shin, Romeo says that “plantain leaf is excellent for that.” It seems that the leaves were pounded into a paste and applied to open sores or to inflamed areas to help bring down the swelling. The juice from crushed leaves can still be applied to skin irritations and insect bites, but for anything more serious, see a doctor.

The leaves of both of these species taste fine in salads, as do those of the seaside plantain (Plantago juncoides). This plant is similar to the English plantain except that its leaves are fleshier, like those of many seaside plants. Also, instead of three veins, the leaves usually have only one vein. The flower stalk of the seaside plantain is generally shorter than that of the other plantains, and the flowering portion is usually longer. The smallest and youngest leaves taste best in salads; the veins in the older ones become tough and stringy.

The leaves of most plantain species can be cooked and eaten as a vegetable. People who want to eliminate plantains from their lawns can go out in the spring while the leaves are still soft and tasty, pull them up, and serve them for dinner. Plantain roots aren’t very deep, and they aren’t nearly as hard to pull up as species with deeper roots, like chicory and dandelion.

Several other common Plantago species grow in North American cities and suburbs, usually as weeds. Plantago aristata, known as bracted plantain or rat-tail plantain, is found in habitats similar to those where English and common plantains thrive. The leaves are much like those of the English plantain, except that they branch right off the stem instead of forming a rosette at the base of the plant. This species is native to the Midwest, where the plants grow on rather dry soils, in meadows, pastures, lawns, and waste areas. Populations are also found locally in eastern and western states.

Another Plantago found in lawns and waste places in the eastern United States, having been introduced from Eurasia, is the hoary plantain, Plantago media. This is similar to Plantago lanceolata, but its leaves are broader, more ovate, coarsely toothed, and whitish.

A few more species are found in urban areas around the country, but they are not included in most field guides. One of these is Plantago purshii, known as Pursh’s or woolly plantain. Its leaves grow in a whorl at the base of the plant. They are narrow, with three veins, and have winged petioles; the main stems are woolly. This plantain is native to the Midwest, most common from Illinois to Ontario, but it has been introduced farther south and to the east.

Rugel’s plantain (Plantago rugelii) is similar to the broad-leaved plantain, except that it’s less hairy, the edges of the leaves have wavy teeth, and the petioles are purplish. This species is native to the East and has been introduced locally west of the Mississippi Valley.

The whorled plantain (Plantago indica), or sandwort plantain, has branched, linear, very slender leaves. This plantain was introduced from Europe and is now found in cities and towns in the eastern and northern states.

PURSLANE

The purslane family, Portulacaceae, has over 100 species in the genus Portulaca, of which only about a dozen are found in North America. The most common of these is a weed called purslane (Portulaca oleracea), an alien from Europe. Although purslane is cultivated in many parts of Europe and Asia, it grows wild throughout much of North America. It is found from Canada to the southern tip of South America. In the United States it can be found from coast to coast. American relatives in the genus Claytonia are the spring beauties. Unlike purslane, which has small yellow flowers, spring beauties have larger, more delicate pink or white flowers, and they grow on richer soils in the woods.

The small yellowish flowers have five petals; they bloom during mid-to late summer and will only open when the sun is out. The plants reproduce by seeds, and they are found growing in fields and waste places, though the soil they grow on is often quite good.

Like most members of the genus, purslane has thick, succulent leaves and stems. They often grow in large patches that lie close to the ground. The leaves are alternate, though they sometimes occur in bunches. Purslane leaves and stems can be eaten in salads or soups, or they can be served as a cooked vegetable. For thousands of years purslane has been consumed in India and Iran, and throughout Europe and Asia, where many different varieties have been developed. Purslane has a rather mild flavor; it lacks the bitterness of many other wild species. Some people dislike its mucilaginous, or gooey, texture, but this quality makes it valuable as a thickener in soups and stews, where it can be used in place of cornstarch or flour. Also, its thick leaves and stems can be pickled like cucumbers. In addition to these uses, you can collect the seeds and grind them into a flour to make gruel, bread, or pancakes. Or boil the plants briefly, pack them in plastic bags, and freeze them for future use.

Purslane

Purslane is native to dry regions of India and Iran. The thick stems and leaves, which conserved water in those lands, have probably proved a worthwhile preadaptation for the urban environments. In arid areas where the sun and the wind can be fierce, plants tend to grow near the ground and have hairy or thick vegetation that protects them from evaporative water loss. As it turns out, water is scarce in many urban environments because of the heat as well as the run-off due to the soil compaction and concrete. Many weedy plants that thrive in arid places also show the capacity to survive and sometimes even thrive, in cities. Purslane is such a plant.

CLOVER

Clovers are members of a very large worldwide family, the Leguminosae, also known as the legume or pea family. All the peas and beans are cultivated varieties of plants in this family, having been selected for the taste of their seedpods or the value of the seeds within. The legume family has representatives ranging from small plants like the clover to shrubs, trees, and vines. The key characteristic that ties the entire family together is the distinctive five-petaled flower. The two lower petals are fused into a keel, which is bordered by two other petals forming wings, with a larger petal behind all of them like a backboard. The clovers usually have heads of small flowers, but when you look carefully you will see that each tiny flower has this general architecture. When most flowers in this family go to seed, they form a simple pea pod. The leaves are usually alternate, compound, and have stipules (leaflike appendages) at their base, although some species have tendrils or thorns instead of stipules.

Red clover

There are almost 100 different species of clovers, and most live in western North America. Some clovers are very well known, being found in lawns everywhere. Their leaves are usually palmately compound, and most leaves have three leaflets. The flowers grow at the end of the stem, where they usually occur in clusters as a head or a spike. They may be white, pink, red, or yellow, depending on the species.

Of the three common white clovers, two are very similar. They are the low, white clovers that are found in lawns. Both of these species were introduced from Europe. They flower from late May until fall and are distinguished by their leaves. The white clover (Trifolium repens) has a light, triangular mark on each leaflet, which the alsike clover (Trifolium hybridum) lacks. The third common white clover is the white sweet clover (Melilotus alba), which is a member of another genus. It is a tall plant, growing several feet high, usually along roadsides and in fields. Its flowers grow in long spikes rather than in tight clusters like the members of the Trifolium genus. It, too, is an alien species.

Another common clover is yellow sweet clover (Melilotus officialanis ), which is very similar to white sweet clover. The other yellow clovers have small, tight clusters of flowers. These are the hop clover (Trifolium agrarium); the smaller hop clover (Trifolium procumbens), which is distinguished by its stalked terminal, or middle leaflet, meaning it has a little stem; and the least hop clover (Trifolium dubium), which has a tiny flower head, much smaller than that of the other two hop clovers.

Red clover (Trifolium pratense) is also an introduced species that is now found throughout the country. This is the common pinkish clover found in fields, along roadsides, and on lawns everywhere. The leaves have pale triangles, similar to those on white clover.

The sweet white and sweet yellow clovers have a distinctive, rich, sweet smell, advertising their blossoms to pollinating insects. Clover nectar, in fact, contains approximately 40 percent sugar. Just to put this in proper perspective, the old Coca-Cola® (now called the Original Formula Classic Coca-Cola©) contains 10.9 percent sugar, and the new Coca-Cola ®, which is sweeter, is 11.9 percent sugar.

As soon as the flowers are pollinated, they droop and turn brown. The young shoots of both the sweet white and sweet yellow clovers can be boiled and eaten like asparagus. The small pealike fruits can be added to soups and stews. Clover flowers and clover leaves, especially the young ones, may be put into salads. Some people dip the blossoms in batter and fry them, making clover fritters.

Most of these clover species can make a major contribution to the soil. Symbiotic bacteria live in small nodules in their roots. These bacteria are able to transform atmospheric nitrogen into a form that is useful and necessary to plants. Farmers have learned to plant clovers in their fields, reducing their need for expensive nitrogen fertilizers.

Besides the clovers, the legume family contains other well-known species and species groups. One such species is alfalfa (Medicago sativa), which has a purplish blue flower. It was introduced to this country from Eurasia and is now widespread everywhere except in the Southwest. It is planted as a forage species. The name comes from the Arabic, al-fasfasah , which means “the best kind of fodder.”

Another member of this family that has been widely written about during recent years is kudzu (Pueraria lobata). This Asian species is well known in the southeastern United States. It has spread like wildfire and now extends as far west as Texas and as far north as Tennessee, though there are reports that populations survive even into Pennsylvania. This vine grows over everything. It is common along roadsides, where it climbs over the trees, growing as high as 100 feet (30 m), using all of the sunlight, and killing the trees. It hasn’t been one of the most popular species in the Southeast, but people are learning to live with it. Acacia and mimosa trees are also members of this family.

PURPLE LOOSESTRIFE

When in bloom, purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is a beautiful plant that makes low, wet areas absolutely gorgeous. After a while, however, those who appreciate the subtle beauty of a wetland may miss the diversity that existed before the marsh was besieged with this alien.

Like many other species that have been naturalized from Europe, purple loosestrife is a plant about which little is known. It is thought to have arrived here during the early 19th century, when settlers probably brought it over to plant in gardens in the Northeast. As with most introduced weeds, little accurate information about its spread has been recorded, which is unfortunate. It appears that purple loosestrife rapidly colonized new areas, but this observation may have been made only because it is such an obvious plant. Its purple blaze is so overpowering that people can’t help noticing it. Other weed species often grow in waste areas or on dry, trampled, urban patches, but this plant moves right into some of the best wetlands and takes over, outcompeting many native species. Because purple loosestrife grows in dense patches, choking out other vegetation, it can have a major impact on a habitat. There are some good qualities about this species, foremost of which may be its colorful beauty. Like it or not, purple loosestrife is here to stay.

Purple loosestrife reaches heights of several feet (1 to 2 m). The stems are stout, woody, and thick; on the larger specimens they will get as thick as ¼ to ½ inch (.5 to 1 cm). The leaves occur oppositely, on both sides of the stem, as well as in whorls of threes. They are sessile, that is, without stems, long and narrow, from 1 to 4 inches long (2.5 to 10 cm). The leaves are usually hairy. The flowers occur in a long terminal spike, each flower having six petals and twice as many stamens.

Naturalists don’t know much about the movement of alien plant species after they have been introduced to this country, but we assume that different plants become established in different patterns. Purple loosestrife, for instance, seems to move rapidly along wet roadside ditches and into adjacent wetlands, where it takes over. Because new plants sometimes appear miles from the nearest established populations, it is likely that the seeds pass through waterfowl, then germinate elsewhere. It is also possible, of course, that some plants are transplanted by well-intentioned people. This may account for several plants that I saw flowering during the summer of 1986 in Central Park in Manhattan.

During the past fifteen years, purple loosestrife has expanded its range throughout the Northeast at a remarkable rate, but instead of starting in a city and then spreading out, like most weeds, this species started in rural communities and is spreading to urban areas. It is now found in all five boroughs of New York City—Staten Island, Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx—but so far it is common only in Staten Island. Presumably it is only a matter of time before its numbers increase in suitable habitats elsewhere. Its color will almost certainly be a worthwhile addition to the urban landscape.

Purple loosestrife, like Phragmites, is a plant that alters a habitat. Once it moves in and takes hold, a wetland may never be the same. Because wetlands attract a wide range of species, it is important that we preserve them. But we can go only so far as caretakers. We can prevent our ponds from filling in and keep our lawns from turning into fields, but we cannot control all the individual species. Such a task is impossible.

Currently, Phragmites is one of the most dominant plant species associated with disturbed urban freshwater wetlands, so any newcomer that increases the diversity should be welcome. People have been complaining for years that Phragmites doesn’t supply enough food and worthwhile material to the wild communities. With a little bit of luck, purple loosestrife may change that in some areas. The drawback will be that shallow wetlands may be overrun by Lythrum. This will only increase the need to cut down old reeds, pull out the canes by the roots, increase the level of the water table, use chemicals to control the plants, or go in and dredge. All these options are expensive, and none offers a permanent solution.

Lythrum, a perennial herb, dies back each year, leaving tall hexagonal stems with a whorled branching pattern. Each node usually contains three or four smaller branches, along with small remnants from the tight clusters of dead flowers. Lythrum is still most common in the Northeast and the North Central states, but it has been found in the Northwest, and it is expected to continue its rapid advance right through the South and across the country, wherever available habitats permit. It is also found in most of Europe and central Asia, and it is spreading in Australia.

Purple loosestrife

Another introduced loosestrife, Lythrum virgatum, also called purple loosestrife, doesn’t have hairy leaves like L. salicaria and is still restricted to a relatively small area in New England.

Three native species in this genus are found on the East Coast. They aren’t as aggressive as L. salicaria, and their flowers aren’t nearly as showy. They are the winged, or wing-angled loosestrife (Lythrum alatum ), which has a four-angled stem that is sometimes winged; hyssop-leaved loosestrife (Lythrum hyssopifolia), which has narrow, alternate leaves and grows in salt marshes; and narrow-leaved loosestrife (Lythrum lineare), which is similar to the hyssop-leaved loosestrife, except that its leaves are even narrower and have an opposite rather than alternate arrangement along the stem. The narrow-leaved loosestrife is also found in salt marshes in the East.

Another related species in the loosestrife family is swamp loosestrife, or water-willow, Decodon verticillatus, that, like the purple loosestrife, is tall, grows in wet areas, and has lavender flowers. The flowers have five petals, are bell-shaped, and occur in bunches in the upper leaf axils. The leaves aren’t hairy.

Other loosestrifes in this country are members of the primrose family, Primulaceae, and of the genus Lysimachia. These species look something like Lythrum, but their flowers are usually yellow rather than pink or purple, and they grow on longer stems. Of these species, few ever occur in urban or suburban settings; they are more often restricted to places yet to be affected by people.

LAMB’S-QUARTERS

Beets (Beta vulgaris) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) are both che-nopodiaceous plants—that is, they are members of the goosefoot family, Chenopodiaceae.

This family contains some 550 species worldwide. One of the genera, Chenopodium (the pigweeds), has about 60 species, 20 of which are found in the United States. Goosefoot, pigweed, lamb’s-quarters, and Mexican tea are the most common members of this group in North America. Probably the most widespread species is Chenopodium album, or lamb’s-quarters. This plant grows as a weed along roadsides and in gardens, fields, disturbed sites, and waste places throughout the country. Small green flowers are common to all members of this genus. The flowers are crowded on spiked clusters originating from the leaf. The plants can attain a height of about 5 feet (almost 2 m) by late summer. The leaves are alternate, simple, and commonly vary slightly with respect to the pattern shown in the illustration.

Lamb’s-quarters are edible. Pick only the young plants, found from mid-spring until autumn. The young shoots grow less than 1 foot (30 cm) high and taste fine raw. If cooked, they taste very similar to spinach. The foliage can be dried out and used in soups or stews. The seeds may be shaken off and fed to birds, along with the seeds of plantain (Plantago spp.), ragweed (Ambrosia spp.), smartweed and knotweed (Polygonum spp.). I’ve also heard that Chenopodium seeds are an antihelminthic, which means they expel intestinal worms, at least for some species of birds. As many as 75,000 seeds are produced by just one mature plant. Native Americans used the seeds extensively, boiling them to make gruel or grinding them into flour. It is interesting to note that when lamb’squarters seeds were taken out from under old buildings in Europe, some still germinated, even after having been there for more than 1,500 years.

Lamb’s-quarters came from Europe and rapidly spread across North America. Mexican tea (Chenopodium ambrosioides), introduced from tropical America, was once confined to the southern states. It now has invaded the middle Atlantic states and is doing well in cities as far north as New York and beyond. Perennial goosefoot (Chenopodium bonus-henricus ), originally brought to North America from Europe to be used as a potherb, has spread through many eastern cities and towns. Unlike the lanceolate shape of Mexican tea leaves, this species has triangular leaves. Another species brought over from Europe, now widespread across America, is Jerusalem oak (Chenopodium botrys). Its leaves are hairy and strongly scented. Strawberry pigweed (Chenopodium capitatum), a North American native, is found in the Northeast, the mountain states, Canada, and Alaska. Its leaves are triangular with wavy teeth. Oak-leaved goosefoot (Chenopodium glaucum) was introduced from Europe and now occurs in the northern United States and south and west to Virginia, Missouri, and Nebraska. The maple-leaved goosefoot (Chenopodium hybridum), nettle-leaved goosefoot (Chenopodium murale), pigweed (Chenopodium paganum), many-seeded goosefoot (Chenopodium polyspermum ), red goosefoot (Chenopodium rubrum), and goosefoot (Chenopodium urbicum) are other closely allied representatives of this genus that are found in urban areas across America.

Lamb’s-quarters