3

TREES

Trees grow in cities all across this country. Street trees that are planted along sidewalks are carefully chosen for their urban-tolerant characteristics. Trees planted in lawns and parks are selected for their beautiful foliage or flowers. But in alleys and along the edges of parking lots, in waste areas and beside railroad tracks, in overgrown fields, woodlots, and the wild areas of larger parks, you will find trees that have seeded in on their own and have grown to maturity without any help from humans. It is interesting to observe these species. What kind of trees are they? How might they have been brought to the cities? What will their future be?

Cities have polluted air, so urban trees have to be ozone tolerant, capable of surviving air that has much more sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide than would be found anywhere else, except perhaps next to a volcano. Northern cities have the added problem of salt, which is spread on the streets and sidewalks to melt snow during the winter. Salt-tolerant species are often among the trees found in these cities. Varieties, cultivars, and specific hybrids are constantly being developed for characteristics that make them more suitable to a particular aesthetic taste or environment. Rapid growth might be a desirable characteristic for street trees, for example, since a low tree is likely to have its branches knocked off or severely bruised by passing trucks. Early-blooming or disease-resistant trees might be suitable in some cities, perhaps a variety that never fruits and therefore doesn’t drop anything that has to be cleaned up. Any of these characteristics bred into a specific strain might make it more likely to be widely used in urban areas.

It is especially important for a street tree to be able to survive periods of drought, because these trees seldom receive any care; their cramped conditions and overly packed soils mean that little water or nutrients ever reaches their roots.

Adaptations to dry conditions include anything that conserves water or increases the tree’s chance of gathering as much water as possible when it is available. Taproots help when a plant needs to penetrate deep into the soil before it reaches water; thick fleshy roots that store water for future dry periods are common among plants adapted to arid climates. Thick hairy leaves or leaves with dense, waxy cuticles conserve water during the heat of the summer by reducing evaporative loss. It is interesting to note that many drought-tolerant species have compound leaves, and that several of the more popular street trees also have compound leaves.

Nowadays, tree species are being transplanted, propagated, and moved around the country, often the world. As a result, it can be difficult to identify certain species found in cities. In rural areas you can usually count on encountering species indigenous to that area, and only those species, but in urban areas you never know what to expect. Many forestry, highway, and parks departments restrict species that may be planted along streets, but restrictions are generally much looser in parks. Because there are parks that have existed for well over 100 years, generations of different administrations have planted species that are rarely documented in files. Since few of the people working for these cities know much about trees, you are usually on your own when trying to identify a species. Your best bet is to start with the most abundant species. Therefore, I will discuss only common species in this chapter—trees you will almost certainly encounter—rather than providing a long catalog of species you might encounter. By knowing a handful of species in each appropriate group, you can become quite well versed on the subject of urban trees.

LONDON PLANE

The London plane tree is a hybrid between two closely related plane trees, the American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) and the Oriental plane tree (Plantanus orientalis). While both trees are prized for their beauty, neither does particularly well in the harsh urban environment. The hybrid between both species, however, possesses a vigor that surpasses that of the original plane trees. For genetic reasons, this is true of many hybrids; it is known as hybrid vigor. Because the Platanus hybrid was unknown during the lifetime of Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of so many 19th-century American parks, those early parks were filled with American sycamores and Oriental plane trees, but neither species thrived. In cities, the American sycamore was prone to sycamore anthracnose, a disease that attacks the leaves and twigs. (A closely related fungus attacks many oak species in cities. It seems that the weakened trees in urban environments are subject to such diseases.)

The hybrid, or London plane tree, often designated Platanus x acerifolia, started to come into its own when Robert Moses, Commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, developed something of a love affair with the species and planted them throughout the city. Before long, the London plane had become virtually synonymous with crowded cities.

The trees have large, simple leaves that grow 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 cm) wide, arranged alternatively on the stems. They are palmately lobed, which means they look very much like the typical maple leaf. In fact, the symbol used by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation of a leaf in a circle, thought by most people to be a maple, similar to that on the Canadian flag, is actually a sycamore. I say sycamore; I’d be slightly dishonest if I said a London plane because the leaves are virtually identical. Their one characteristic that is unlike all other trees planted along sidewalks is the hollow petiole base that covers a bud. Underneath the point where the stem of the leaf attaches to the twig, you’ll find the bud. I hate to put this in writing because I don’t want to be responsible for tens of thousands of London plane leaves, as well as those of other trees with palmately lobed leaves, being periodically plucked in an attempt to expose the hollow petiole and bud beneath, but somehow I think I can live with that on my conscience. Pluck sparingly.

The distinctive bark of the London plane tree is smooth, with thin, brittle flakes exfoliating, exposing a greenish or brownish color underneath that creates a mottled effect. The seed heads, or seedballs, of the London plane occur singly and in doublets, triplets, and quadruplets. This tree grows rapidly, reaching heights of 80 to 100 feet (25 to 35 m). In fact, among those species that do well in cities, only the cottonwood (Populus spp.) and the silver maple (Acer saccharinurn) seem to grow faster.

The wood of the London plane is relatively strong, hard, and heavy. Because it is hard to split, it has been used to make veneer, flooring, boxes, barrels, crates, and butcher blocks. When exposed to moisture and bacteria, however, it readily rots, which is why many of the older specimens are hollow inside.

The London plane has been planted along roads, highways, and city streets all across the country, and it has the capacity to grow almost anywhere. It is fairly tolerant of ozone and sulfur dioxide pollution, and it can survive considerable concentrations of salt. In addition, though this tree does best on moist, well-drained soils with a pH ranging from 6.5 to 7.5, it is adaptable and can withstand wet conditions, drought, and other pHs.

Although the London plane tree has been believed to be resistant to the anthracnose fungus (Gnomonia platani) that attacks the American sycamore, it has been losing its edge. In New York City an early leaf blight each spring can kill the young leaves and result in partial or even complete defoliation. Another type of damage can be seen in the small to large brown blotches that appear along the midribs and lateral veins of mature leaves; these can result in some defoliation. To control this disease, which weakens the trees but seldom kills them outright, it helps to prune the diseased leaves and to water the trees during droughts. It is also helpful to fertilize the trees properly, which is best left to a private arborist. Communities often raise money for professional tree care, with permission from the local parks department or the city agency that oversees street trees. The contractor fertilizes the trees with a very long injection needle, directing a water-soluble fertilizer about 8 inches (20 cm) deep to get below the compacted surface layer. The degree of reinfection can be reduced by thinning the dense canopies, pruning the deadwood, and removing leaves and twigs shortly after they fall. Local citizens often pressure their local parks department to use chemicals to control anthracnose, but there is no reason to believe that such care has any long-term benefits.

TREE OF HEAVEN

The unplanned and untended woodlands in and around cities are constantly regenerating themselves. Many of these woodlands have trees that seeded in on their own; when they die, they will be replaced by other trees that grow without human help. Here you will find some species of trees that would not have been found in such a region 100 or 200 years ago. Some of the newer species were brought in for planting; later they proved capable of moving into open areas, where they successfully competed with the local species, regenerated themselves, and have become a part of the urban landscape.

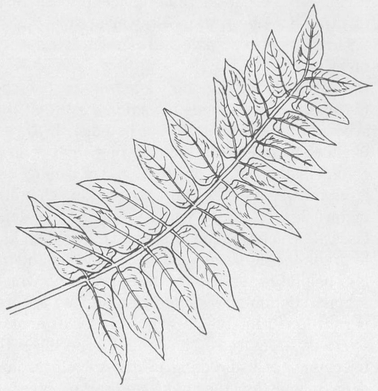

One of the most amazing self-regenerating species is the tree of heaven, or what some call the tree that grows in Brooklyn, Ailanthus altissima. This tree was transported from China to England in the 1750s, then introduced to the United States in 1784. Frederick Law Olmsted used it in New York City’s Central Park because he liked the tree’s tropical appearance. It is one of the last trees to sprout its leaves in the spring, but finally its large buds swell, developing into long, pinnately compound leaves that often reach a foot or two or even three feet in length. At first the leaves are yellowish green, but in time they darken to a rich, dark green; by June the trees begin to blossom. These trees are dioecious—that is, the male and female reproductive organs are borne on different plants. The male trees grow foul-smelling, stamen-bearing flowers, while the female trees sprout greenish white pistil-bearing flowers. The pistillate flowers later develop into fruits, each bearing one seed, somewhat similar to those of the ash, elm, and maple. These reddish green and reddish brown seeds are called samaras, and they appear in clusters.

Tree of heaven

When in seed, some of these trees are absolutely stunning. Many people will strenuously disagree, of course, since it has become fashionable to grumble about this species, but that attitude is largely a response to the popular view that this tree has gotten out of control and now seems to be growing practically everywhere. Actually, the tree of heaven doesn’t grow “practically everywhere.” It doesn’t compete at all well with native species on rich, undisturbed soils. But in cities, where rich, undisturbed soils are hard to come by, this tree does tend to crop up in unlikely places.

In the fall, when the thin, light, twisted samaras have dried out and turned brown, thousands are simultaneously picked up by big gusts of wind. Becoming lodged in cracks in the sidewalk, in crevices along the edge of a building, or in vacant lots or alleys, they set root. Indeed, these trees sprout up in cities like weeds, but what differentiates them from most herbaceous weeds is that they don’t die back each year; in fact, they are next to impossible to kill. The more you cut them back, the better they seem to like it. As it turns out, while most plant species put a large portion of their effort into the part of the plant that extends above the ground’s surface, Ailanthus invests a large percent of its resources in its roots. As a result, by the time you cut the tree down, it has so much energy stored underground that it will have no problem sprouting up again and again. Storing vast reserves appears to be a powerfully adaptive attribute for any plant that has to survive hard times, especially if these reserves are not vulnerable to herbivores. Cacti store most of their reserves above ground in their large, fleshy tissues: trees of heaven store much of their reserves underground, beyond the reach of virtually everything. This tree was the major symbol of life and survival in Betty Smith’s 1943 novel, A Tree Crows in Brooklyn.

Ailanthus grows faster than almost any other city tree. But like many other rapidly growing species, it has weak, brittle wood that is easily damaged and broken by wind and ice. This causes a problem in cities, because no municipal government wants to be accused of planting dangerous trees that crack and fall on people. However, to my knowledge, no one has ever been killed by a tree of heaven, at least not intentionally.

The common name, tree of heaven, appears to be attributable to the fast growth and eventual heights reached. The average height is probably 40 to 60 feet (12 to 18 m), but many specimens, growing in favorable conditions, attain heights of 90 to 100 feet (27 to 30 m). The scientific name, Ailanthus altissima, means “tallest of the trees of heaven.” It was probably chosen because this species is the largest in its genus.

This tree, as I indicated earlier, suffers from a bad public relations problem. Its human enemies regard it as a weed that will sprout up anywhere. But that seems to be a good thing, not something to complain about. Given half a chance, a few Ailanthus trees will transform a scruffy block into a classy area with shade trees that look as if they were planted long ago. And what if they are the much-maligned “trashy weed trees” that are practically impossible to kill? More power to them.

GINKGO

As a member of an ancient group, all of whose species except one are extinct, the ginkgo is credited with being a living fossil. This is one of the oldest of all living trees, with a fossil record that extends back 100 million years virtually unchanged. It has been said that city dwellers who walk by a ginkgo should be as surprised as if they were walking by a crocodile. I’m not sure the analogy is valid, but I like it. The ginkgo came to this country from Japan, which imported it from China. It is widely planted as an ornamental and a street tree, but it is almost unknown in the wild. Other species have been bred in captivity when they became totally extirpated from their native region, but this is a unique situation. The ginkgo tree is now planted all over the world, but it does not seem to grow in China, Japan, Europe, or the United States beyond the spots where it has been planted. No one knows why.

Ginkgo

This species, Ginkgo biloba, gets its name, ginkgo, from the Chinese gin-yo or gin-go, which means silver apricot, a fair description of the fruit, though it is smaller than an apricot. The ginkgo is also known as the maidenhair tree because its parallel-veined, fan-shaped leaves look like those of some maidenhair ferns. I don’t find the name very helpful because, of the many species of maidenhair ferns, few look similar to the ginkgo. One species of maidenhair fern, however, that is currently very popular in plant stores in New York City has leaves that do look almost exactly like the ginkgo’s.

Besides having fan-shaped, parallel-veined leaves with irregular lobes at the end and an indentation in the middle of the fan, the ginkgo’s rather small leaves are usually only a few inches (5 to 8 cm) across, somewhat leathery in texture, and don’t have a midrib.

There is a chance that the name maidenhair fern was adopted for this species when plant taxonomists thought the ginkgo was a close relative of the ferns. More recently though, rather than being grouped with the ferns, it has been ascertained that it should be assigned to its own class, Ginkgoae, even though other plant taxonomists only place it in its own order, Ginkgoales. Nevertheless, it is a member of the gymnosperms, which also include the cycads and the conifers. Unlike the ferns, these are all seed plants, or spermopsids. The gymnosperms are among the most successful plants in the world; pine, spruce, and fir trees constitute about one-third of all the existing forested areas of the world.

The seed plants, Spermopsida, represent one of the several subdivisions within the Tracheophyta, or vascular plants. More primitive vascular plants include the ferns, horsetails, and club mosses. The conifers and the flowering plants represent the more recent and currently most successful seed plants.

One of the main advances of the pines over the ferns was that they no longer had flagellated sperm cells. The pollen of the cycads and ginkgoes is carried by the wind to the ovules, but their pollen tubes still produce flagellated sperm cells that swim a short distance to reach the egg cells. This primitive characteristic is retained from their ancestors.

In 1900 the ginkgo was just becoming popular in Washington, D.C., and New York City, though it was still far from abundant. Because of the tree’s beauty, as well as its ability to survive the gamma radiation, sulfur dioxide, and ozone pollution of the cities, it soon became one of the more widely planted trees in cities across the country. Given the right conditions, such as good soil in a city park, a ginkgo will grow as tall as 60 to 100 feet (18 to 30 m). As a street tree, though tolerant of dry conditions, it does better when the soil is kept moist rather than wet. Care should be taken not to let too much residue from winter saltings reach them, however, because these trees are not particularly salt tolerant. The soils in sidewalk tree pits often become compacted from foot traffic, but the ginkgo is able to tolerate this stress.

When the trees were first planted in American cities, males and females were used at random. In time, however, people tired of the odor and mess created by the ripe and overripe fruit of the female; today many parks departments avoid planting females. But in some older parks, where large female specimens still thrive, it is not unusual to find Chinese people collecting the fruit in the fall and early winter. The small, plumlike fruit is edible, but the flavor is both disgusting and pleasant, if that is possible. This is a bizarre fruit: you won’t know what I mean until you taste one. It isn’t the malodorous outer husk that the Chinese are after, however. Inside this covering is a silvery white kernel. People don’t eat these kernels raw because they taste like rancid butter, but when boiled in a soup for a long time, they impart a rich flavor. The kernels are also roasted like nuts. Ginkgo fruits are sold at high prices in Chinatown in New York City. The Chinese also use the raw seeds to treat cancer, but great care is taken because the uncooked seeds can prove fatal.

In the autumn ginkgo leaves turn golden yellow and fall off. Because the trees can tolerate hot, dry summers as well as winter temperatures that drop as low as — 10°F (—23°C), they have been successfully grown throughout the United States, except in the coldest areas of New England, the Great Plains, and parts of the Great Lakes area. Ginkgoes do not suffer from any serious pest problems, perhaps because the waxy cuticular layer of the leaves is resistant to most common pathogens.

HONEY LOCUST

The honey locust (Cleditsia triacanthos) became popular in this country in the 1940s. At that time, American elms (Ulmus americana), which were very common street trees in the East, were hard hit by Dutch elm disease. Cities lost row upon row of beautiful old elms that had grown up along with the communities they adorned. The elms had to be cut down as soon as they showed signs of the disease; otherwise it would spread to the trees nearby. The honey locust became popular as a replacement.

Probably originally occurring along rivers and streams in the wild, the honey locust was the beneficiary of widespread agriculture. As areas were opened up for farming, cattle ate the sweet seedpods. When the seeds passed through the animals’ digestive systems, gastric juices softened the hard outer seed coat, facilitating germination. As a result, honey locusts rapidly spread through pastures from central Pennsylvania, south to Alabama, west to Texas, and as far north as southeastern South Dakota.

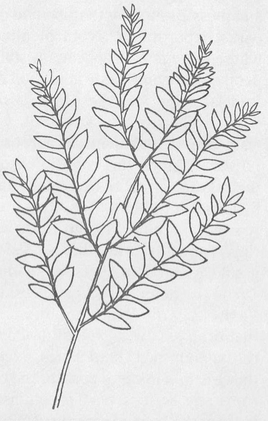

Honey locust

When Frederick Law Olmsted was seeking tree species for the many city parks he designed, he would bring in new species to a city if he thought they would suit the area aesthetically, and could survive there. He planted several clusters of honey locusts in Central Park, where they quickly grew into fine specimens; after that, the tree was well on its way to being planted elsewhere.

The honey locust has pinnately compound leaves, which means there are leaflets arranged on both sides of the midrib. If you look closely, however, you will see that it also has bipinnately compound leaves on the same tree, usually on the same branch. Bipinnately compound leaves are doubly or twice pinnate, meaning that the main axis is also branched, as illustrated. The black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) has pinnately compound leaves as well, but unlike the honey locust, Robinia has showy, fragrant flowers. Another street tree with bipinnately compound leaves that is popular in some cities is the Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioica).

The minute, hardly noticeable flowers of the honey locust rapidly ripen into long pods, which you cannot miss. While the pods are still young, they are soft and green, and their pulp is sugary sweet, which accounts for the “honey” part of the tree’s name. The name “locust” has a more circuitous origin. According to the New Testament, when Saint John went into the wilderness, he lived on “honey and locusts.” The locusts were actually the long, sweet pods from the carob tree, Ceratonia siliqua. When ripe, the hard seeds inside the pods rattled like locusts, thus the confusion in names. Even though the honey locust is unrelated to the carob, because of its long, dark pods, it came to be called a locust, too. Actually these trees have had many names, but honey locust is now by far the most widely used. Some honey locust trees have thorns, and for a brief period they were called Confederate pin trees, because the thorns were used to pin together the torn uniforms of Confederate soldiers during the Civil War. The long spines of these trees act as a deterrent to any animal wishing to climb the tree to eat the young pods. Squirrels never climb these thorned trees. The pods develop their sweet taste so that when they ripen and fall to the ground, they will be eaten. This effective dispersal mechanism is used by many pod-bearing trees, however for the honey locusts, it did not take effect until they became a popular replacement for elms. Their widespread use led to the development of a thornless variety (Gleditsia triacanthos inermis), which is rapidly becoming predominant in urban areas in the East.

The honey locust is popular in eastern cities, probably for several reasons. For one, it tolerates a wide range of climate conditions, very wet to very dry. Its popularity may also be related to the way light filters through the compound leaves, creating a pleasant mottled effect on city streets. This tree’s spreading branches and open, rounded crown also make it look attractive along city streets. Remember, too, that street trees are sometimes damaged by trucks pulling up to the curb or by kids locking their bicycles to the trunk. Such abuse can damage the way a tree grows and the shape it develops, but the honey locust’s spreading, random shape somehow allows it to compensate for any imbalance stemming from an injury, and to still mature into an attractive tree. It should be added that in the autumn, when the leaves of other trees are turning brown, honey locusts brighten up, turning a golden brown or, if you prefer, a honey color. When cold weather arrives, the leaflets blow away, leaving the long, twisted, dark brown seedpods hanging on the bare branches; the pods then fall during the winter.

In addition to the trees discussed above, there are other urban species with compound leaves. They include the green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), the Japanese pagoda tree (Sophora japonica), the golden rain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata), and the mimosa, or silk tree (Albizia julibrissin). These trees may not be that drought tolerant or disease resistant; they may have been chosen as street trees because people find them attractive or because their leaflets are small and easy to clean up in the autumn.

PIN OAK

Another tree that has been widely planted in suburbs and cities is the pin oak (Quercus palustris). This native American species was originally restricted to an area ranging from Vermont and Massachusetts south to Virginia and Tennessee, west to eastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma. It was not a fashionable tree in this country, but it has been popular in Europe since the early 19th century. About 100 years later, it finally began to catch on in the United States. After being planted first in Washington, D.C., and parts of New York City, especially in Queens, it slowly became one of the most popular street trees in this country.

Pin oaks grow relatively rapidly. They rarely attain the size and age of many of the other oaks, but they are more likely to thrive in urban conditions. The pin oak’s main trunk usually runs straight up, like a conifer’s, almost to the top, where it branches into many slender boughs. The wood is strong and resistant to wind and ice damage, though the lower branches, instead of falling off, typically stay attached and droop downward. This deadwood seems to encourage decay, which attracts wood borers and damages the value of the wood, but since pin oaks are primarily planted for their tolerance of urban conditions, this isn’t a drawback.

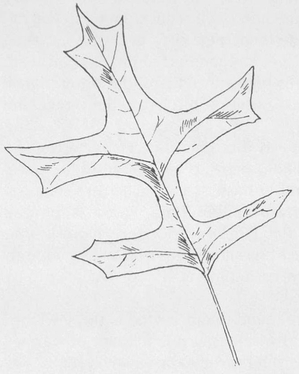

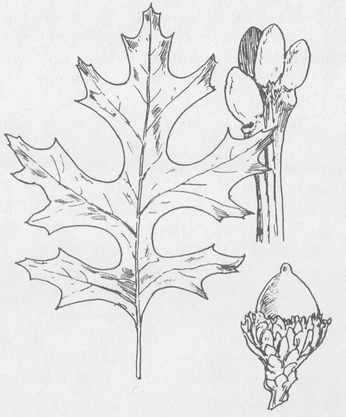

Pin oak leaves usually have five lobes, though they may have seven or even nine. They are oblong, 3 to 6 inches long (7.6 to 15.3 cm), with slender petioles that are 1½ to 2 inches long (3.5 to 5.1 cm). The lobes are bristle-tipped with rounded notches, and both sides of the leaves are bright green. Pin oak acorns are only about ½ inch (1.3 cm) long and a ½ inch (1.3 cm) in diameter. The shallow cup at the base of the acorn is saucer-shaped with thin, small, reddish brown scales. On the trunk the bark is grayish brown and slightly furrowed, while the bark on the upper parts of the tree is smooth, light gray, and often striped like that of the red oak (Quercus rubra). Some of the pin oaks planted as street trees are hybrids between pin oaks and red oaks.

Pin oak

The pin oak gets its name from the distinctive pinlike or spur-shaped branchlets on the main branches. In outline the pin oak is a single, mastlike trunk that ascends straight up through the center of the tree. Many pin oaks turn a yellowish brown in the autumn. Others turn from reddish brown to purplish red, or even brilliant red.

Recently the horned oak gall has become a problem where pin oaks are planted in large numbers, as in New York and other cities. This gall is caused by a tiny black wasp, Callirrhytis cornigera, which lays its eggs in pin oak twigs. These eggs slowly develop into galls. Almost two years later, tiny, parthenogenic female wasps emerge from the twig galls. They fly to the tree’s foliage and, without having to mate with males, deposit their eggs in the leaf veins. The larvae cause vein galls to form; in midsummer both male and female wasps emerge again, and another life cycle is complete.

Horned oak gall quickly spreads to all the nearby pin oaks until all trees in the area are infected. The ugly galls make the trees look terrible, and the trees may die before their time. When the infestations aren’t very bad, the diseased limbs can be pruned; this will reduce the wasp population, but it will not entirely eliminate them. Few city agencies concerned with trees bother to prune the galls off all the infected pin oaks. Instead, they recommend that infected trees be fertilized and, during droughts, watered. This strengthens the trees so they can tolerate the weakening effects of the gall.

The pin oak also is susceptible to iron chlorosis, characterized by leaves that turn yellow. This condition seems to be a result of the tree’s inability to absorb iron from neutral or basic soils. Usually the chlorosis only detracts from the overall appearance, but it also weakens the tree and may eventually prove fatal. To counter the effects of chlorosis, you can spray the foliage with a soluble iron salt, such as iron sulfate, an iron solution can be injected into the tree, or, better yet, an iron chelate can be put into the soil around the tree.

Many other species of oaks are found in cities. One is the sawtooth oak (Quercus acutissima), an import from Asia. It is tolerant of warmer climates and does well in harsh sites, but has yet to be widely tested.

The white oak (Quercus alba), though beautiful, long-lived, and popular, is not used often in cities, mainly because it is difficult to transplant.

Black oak leaf, buds, and acorn

Because high success ratios are imperative when hefty fees are paid to have trees dug up and transplanted, any tree that does poorly rarely becomes a favorite. Where white oaks have survived transplantation, they usually do well. Generally they are confined to larger parks, however, rather than along city streets.

The swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor) isn’t often found in cities, but it is seen in the wild, doing quite well under conditions that few other species could survive—including poorly aerated, compacted soils with high clay contents. With this in mind, it might be worth looking into this species as an urban candidate.

In the Midwest, the shingle oak (Quercus imbricaria) has been used extensively, but it is still largely restricted to this area.

A tree that was thought of as a southern species, the willow oak (Quercus phellos), has been widely used in southern cities as a street tree for years. More recently this oak has been found to do remarkably well also in northern cities. Because of its narrow, willowlike leaves, it adds variety to the urban landscape and should be used and appreciated. However, keep this important advice in mind if you plan to take seeds from any species for propagation: if the species has a southern range and you are interested in bringing it farther north, you should take seeds from the northernmost part of its range. Otherwise, the mix of genes that you get may not be able to tolerate the harsh northern winters. This advice also works in reverse, in case you plan to move a northern species to a location farther south.

The English oak (Quercus robur) is native to Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia. It has been successfully used as a street tree in Philadelphia, but there have been problems with it in the Boston area. Since there is wide variation among individuals of this species, it may be that the appropriate seeds were not used in Boston.

The scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea) is very similar in appearance to the pin oak, having a straight trunk and elliptical leaves, with five to nine narrow, toothed, pointed lobes. This tree can be counted on for excellent red foliage in the fall. Also, it appears to be less susceptible than the pin oak to iron chlorosis.

As you walk around wild, wooded areas in the larger city parks observing the species of trees that are regenerating, you will notice that while many of the older trees may be white oaks (Quercus alba), black oaks (Quercus velutina), or red oaks (Quercus rubra), which were often there before the city was built up around them, the most common oak species among the new trees that is replacing the old tends to be the pin oak. This is especially apparent in cities where pin oaks were never common until they were brought in and planted in the parks and on the streets.

WHITE MULBERRY

The mulberry was known thousands of years ago in China, where it was cultivated as a food source for silkworm caterpillars. In 1623, King James I had mulberry trees and silkworms’ moth eggs sent to the Virginia colony in the hope that a silk industry would take hold there. Thirty years later, to provide a greater incentive to farmers, a law was enacted requiring every planter who hadn’t raised at least 10 mulberry trees for every 100 acres to pay a fine of 10 pounds of tobacco. At the same time, 5,000 pounds of tobacco were promised to anyone who produced 1,000 pounds of silk in a single year. In response to this legislation, a member of the Virginia legislature planted 70,000 mulberry trees on his estate by 1664. In 1666 the law was repealed when it appeared that the silk industry had taken off, but the industry soon dissolved because new immigrants had considerable overhead and preferred to turn an immediate profit. So the culture of rice and indigo was introduced. Unlike silk culture, these crops did not require several years of start-up time; they brought in money almost from the beginning.

White mulberry

During the 1820s, the U.S. silk industry again showed signs of life. William Prince, who owned a nursery in Flushing, New York, was importing different varieties of mulberry trees from all over the world, but multicaulis, a cultivar of the white mulberry (Morus alba) brought over from the south of France, was one of the most sought-after breeds. The tree caught on rapidly among those attempting to get in on the ground floor of the revived silkworm industry. Prince plowed a substantial investment into propagating these trees, and while he was filling orders as fast as he could get them out the door, he was also gambling much of his fortune on raising silkworms himself. Prince, as it turned out, was one of the few who succeeded in the venture. In spite of extensive efforts, all hope of establishing a silk industry in this country had been abandoned by 1900.

Although the American silk industry is now only a paragraph in the history books, it did serve to introduce a decorative and urban-tolerant tree to this country. That tree was the white mulberry. It was brought to the United States from Europe, but it is a native of China. Some 1,500 species of mulberries are found around the world, most of them in the tropics. Of those that will live in more temperate climates, the white mulberry was found to be a better host species than its American relatives, which include the red mulberry (Morus rubra), found from Massachusetts to southeastern Minnesota, south to southern Florida, and west to central Texas.

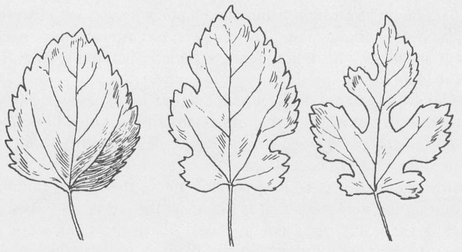

The leaves of the white mulberry can be either lobed or unlobed, as illustrated, with both types usually present on the same tree. White mulberry fruits look a bit like blackberries, but they vary in sweetness and in color, ranging from white to red or purple. The fruits are eagerly taken by birds and small animals. The seeds deposited in their feces have helped spread the trees through many habitats, and now the white mulberry tree is considered almost a weed species, sprouting up practically everywhere. It is a fast grower when young, and it can tolerate a wide range of conditions. This tree does well on a range of soils with different levels of compaction, in moist as well as dry conditions, and in the presence of salt. It does best on soils that vary in pH from 6.5 to 7.5. In spite of these advantages, the white mulberry is rarely planted along sidewalks because its fruit, when it drops, causes too much of a mess. There are, however, several nonfruiting cultivars, including the kingan, maple leaf, and stribling, which are often planted in public areas where the fruits would be an inconvenience.

The red mulberry tree is often confused with the white mulberry, but it is not difficult to distinguish between the two species. The leaves of the red mulberry are much larger, with hairy surfaces and long pointed tips. Do not count on being able to tell the two trees apart by the color of their fruit, however, since the white mulberry’s fruit, as I said earlier, varies widely in color.

COTTONWOOD, POPLAR, AND ASPEN

The willow family contains both the poplar (Populus) and the willow (Salix) genera, which in turn contain about 350 species between them, though the willows are far more numerous than the poplars. Cottonwoods, poplars, and aspens are all in the genus Populus. These trees are found around the world, but are most common in northern temperate and arctic regions. The family has about 60 native shrubs in North America, about 35 native trees, and another 5 or so trees that have been introduced and are now reproducing on their own. By some counts, there are 15 native Populus species in North America.

Cottonwood

All members of this family have alternate, simple leaves, which are usually toothed. Paired glands or stipules appear at the base of each leaf. The male staminate flowers and the female pistillate flowers appear on separate plants. The flowers are very small and are bunched together along narrow catkins. The members of the willow family are often associated with moist and wet soils because that is where the seeds germinate best. When they land on the water, they are blown or washed to the shore, often to moist, suitable soils. However, when they land on dry soils, the seeds rapidly dry up and are unable to germinate. Although they grow wild in wet areas, these trees usually do rather well when planted on drier soils.

The seeds are very small with long cottony hairs. The tree’s common name is derived from the appearance of bunches of these seeds that look like cotton when they clump together.

The eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides) is common in eastern cities and suburbs. Its large-toothed leaves are simple, alternate, and are shaped like triangles, with two corners rounded off and a third corner that comes to a long point. The shape is a cross between a triangle and a semicircle, with toothed edges. The leaves are thick and coarsely veined, 3 to 7 inches (7.5 to 18 cm) in length, often as broad as they are long. They are bright green and shiny above, paler below, with a light yellow midrib. The stalks are slightly flattened, often with a reddish tinge, and with small glands near the tip. The bark of the young trees is thin, smooth, and a greenish light gray color; it becomes more uniformly gray and deeply furrowed on the older specimens. Mature cottonwoods commonly reach heights of 80 to 100 feet (24 to 30 m), and can attain diameters of 3 to 4 feet (1 to 1.3 m). Most of the larger cottonwoods can live 75 years; on occasion, they even reach an age of 200 years. Early on, farmers began to plant cottonwoods widely because they grow very rapidly. Young specimens will grow from 2 to 5 feet (.6 to 1.5 m) a year on rich, moist, well-drained soils. Mature trees have a broad, spreading crown. This is one of the best shade trees when rapid growth is of primary importance.

Farther west, the plains cottonwood (Populus sargentii) is found in the prairie country of west central Canada and the United States. It has more ovate leaves. The narrowleaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) has narrow, willowlike leaves from 2 to 4 inches (5.2 to 10.4 cm) long, and from ½ to 1 inch (1.3 to 2.5 cm) wide. It is found most commonly through the western mountain states, usually along streams at altitudes of 5,000 to 10,000 feet (1,500 to 3,050 m). Narrowleaf cottonwoods are frequently planted as street trees in the Rocky Mountain region.

The Lombardy poplar (Populus nigra var. italica), a variety of black poplar (Populus nigra), is native to Europe and western Asia. Most people have seen this tall, spirelike tree. It, too, is planted for its rapid growth. Its compact crown makes it popular among those who wish to have a leafy border that blocks the view and breaks the wind. The Lombardy poplar seldom lives more than 50 years. These trees are often blown down during severe windstorms. The columnar look is so much admired that similar looking varieties of other species have been developed. They include varieties of crab apple, elm, ginkgo, locust, maple, mountain ash, oak, and pine. These varieties usually have such names as columnaris, erecta, fastigiata, or pyramidalis

Another closely related species—a native of Eurasia that was from Europe—is the white poplar (Populus alba). It has toothed leaves, usually with three to five lobes, which are dark green on one side and whitish and woolly on the reverse side. White poplars, unlike other trees in this family, often have several trunks. These trees have taken quite well to some of the wilder areas in urban parks, where their seeds have germinated, taken root, and grown, allowing the trees to become naturalized.

Quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) is another species in this familiar genus. This tree’s leaves quiver, shake, rustle, and quake almost all the time. It isn’t the only Populus with trembling leaves, though. Cottonwood, bigtooth aspen (Populus grandidentata), and several others have leaf stalks that are long and flattened, especially at the base near the petiole, and this architecture is what perpetuates the leaves’ constant motion. This peculiar adaptation may keep the contents of the leaves’ cells moving around, increasing their photosynthetic efficiency, or it may give the trees a distinct appearance that attracts birds and insects which may benefit the tree in some way. The quaking motion may even shake eggs or insects off the foliage to prevent them from eating the leaves.

The quaking aspen’s leaves flutter more easily and gracefully than those of the other quaking trees. This tree has a wider range than any other North American tree; it is native from New England and Labrador across to Alaska, and south along the Rocky Mountains to Mexico. But it is absent from most southern states east of the Rocky Mountains. The leaves are nearly round in outline, with 20 to 40 small teeth on each side. They are 1½ to 3 inches (3.8 to 7.6 cm) in diameter, thin, and firm, and they turn a distinctive golden yellow in autumn. This is a common roadside tree in disturbed areas. Quaking aspens are a little different in the West, where the leaves are thinner and rounder; these turn a paler lemon yellow in the fall.

The bigtooth aspen’s leaves are slightly larger than those of the quaking aspen. These leaves also have fewer teeth, only about five to fifteen on each side. This species grows faster, gets a little larger, and appears to be more resistant to disease, but its range is more restricted; it is native from Nova Scotia south to North Carolina, west to Missouri, and north to Minnesota.

Many of the species in this genus, including both of these aspens and the eastern cottonwood, are thought of as pioneer species because their small seeds are easily blown by the wind to wide-open spaces where they will readily germinate and rapidly form large clones from shoots off the roots. After aspens move in, seedlings of conifers, hickories, maples, and oaks, all of which are more shade tolerant, readily grow beneath them. Within 100 years or less, only a few aspens will remain; the forest will be dominated by other species. However, in some environments other species do not displace the aspens. Several aspen clones have been aged, and one was believed to be approximately 10,000 years old.

In urban and suburban areas, land is constantly being disturbed, leaving open areas that are perfect for pioneer species to move into. Much work needs to be done to determine just what it takes for species to germinate in cracks in the pavement, along roadsides, in hot gravel, and so on. It would appear that the seeds and the seedlings need to be able to tolerate rapidly fluctuating temperatures, including the extreme heat of the summer. They also need to tolerate different moisture conditions, varying pH levels, and what for other species might be inadequate nutrients. Repeatedly we find the same characteristic species growing along roadsides and in abandoned parking lots and old fields; it shouldn’t take too much work to find out what allows these species, to the exclusion of others, to move in and flourish, while most species are relegated to rural areas.

Hybrid poplars are very widespread in parts of Europe, where they are used in parks and lawns and along streets. They are favored for their beauty, their rapid growth, the relative ease with which they may be transplanted, and their hardiness in urban environments. Few can be seen in American cities, though, partly because they constantly drop dead twigs, which can become a maintenance problem, and because the females produce prodigious numbers of the cottonlike seeds, which blow everywhere. For these reasons, and because they are short-lived, they have yet to catch on as a street tree in many U.S. cities. However, advertisements appear regularly for these poplar hybrids, with accompanying promises of growth rates of 6 feet (1.8 m) a year. It’s true that these trees grow rapidly, but they require optimal conditions and care, and as a result many who plant them never realize the advertised promises. One that has a narrow oval shape and grows fast is a hybrid between Populus maximowiczii and Populus trichocarpa. This hybrid is unusually tolerant to different soil conditions. Another fast-growing hybrid with a columnar shape is a blend of Populus charkoviensis and Populus incrassata. One columnar hybrid, which has small leaves and many small branches, is a mixture of Populus deltoides and Populus caudina.

Because so many different species and hybrids have been planted in cities and suburbs, it is not at all unusual to find poplars hybridizing on their own. Hybrids have been found in Central Park, where both Lombardy poplars and eastern cottonwoods were planted. The cross between these two species is known as Populus x canadensis.

WILLOWS

Although poplars, cottonwoods, and aspens, all in the genus Populus, are members of the willow family, the willows in the genus Salix are far more numerous. There may, in fact, be as many as 70 to 100 different willow species in North America.

Most willows are found in low, wet areas in rural regions. Those species that grow in built-up areas are sometimes difficult to identify because of the readiness with which they hybridize with one another. This problem is compounded by the similarity of so many of the species to begin with. Most have long, narrow, finely toothed leaves. The buds, arranged alternately and often right next to the twig, are usually small and single-scaled. The twigs tend to be long and thin and are often brightly colored.

The most familiar tree in this genus is the weeping willow, but this common name actually refers to a group of closely related species and hybrids, all of which have narrow, lance-shaped leaves, and long, thin, hanging branches. The most common is Salix babylonica, which is native to China. Because it doesn’t do very well in the northern United States, it has been crossed with the crack willow (Salix fragilis) to produce a cold-tolerant hybrid.

The crack willow was initially brought over from Eurasia during colonial times and is now widely distributed from Newfoundland south to Virginia, west to Kansas, and north to North Dakota. Its wood was used to make the charcoal used in gunpowder. The tree spread rapidly, being planted for its shade and beauty. One of its problems, however, is that the brittle branches crack off during high winds, strong rain, heavy snow, or ice. This is a problem to varying degrees with most members of the willow family, and because the twigs tend to clog sewers, causing a significant maintenance problem, city officials usually avoid planting them along streets and highways.

One of the more widely planted hybrids of crack willow and weeping willow is the Wisconsin, or Niobe weeping willow (Salix x blanda), which is especially popular in the Midwest. Another popular hybrid is the golden weeping willow (Salix alba var. tristis [var. vitellina pendula]). This is a variety of the white willow (Salix alba), a Eurasian species that is easily recognized by its bright yellow twigs, but its leaves are very shiny, and the twigs are much longer. It is thought to have been derived from another cross between Salix fragilis and Salix babylonica. Weeping willows and the black willow (Salix nigra), a native of the eastern United States, are commonly planted in low, wet areas in city parks and backyards.

The pussy willow (Salix discolor) is known by many for its fuzzy catkins, which appear during the spring. With the warmer weather they expand, revealing the tiny flowers that were concealed in the buds located underneath all the fuzz throughout the winter. Usually found in wet areas, they seldom exceed a height of 25 feet (7.6 m), and are most often only 10 to 20 feet (3 to 6 m) tall. The pussy willow belongs to a group of shrubby willows that are highly variable and very difficult to identify. Although few of these willows have wood that is useful, they are appreciated for their rapid growth and their ability to sop up water and thrive in areas few other trees could tolerate.

The bitter bark of the willows contains salicin, which was used during the 18th century to treat rheumatism and diseases of a periodic nature, such as malaria. Salicin is a bitter phenolic glycoside that is distasteful to many insects. While it protects willows from insect attack, it has beneficial physiological effects on humans, which explains its use in acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin. The drug is now manufactured synthetically.