4

INSECTS AND OTHER INVERTEBRATES

Insects are the most widespread, diverse, and incredibly successful animals to ever live. They are among the most common organisms found in cities and suburbs. On the decorative plants found in corporate lobbies, for example, you’ll find mealybugs, aphids, scale, and a host of other pests that are perhaps too well known to horticulturists. Many of the species of insects living in downtown lobbies were brought to this country from the tropics and cannot live outdoors in our more northern climates, but they thrive in such well-protected microclimates.

Every urban home has a wastebasket, stove, sink, toilet, and refrigerator, and many have cases of books and stacks of papers. All these objects attract insects. Most homes have a few species. Houses with basements may have more than a few. Apartment dwellers may occasionally have to deal with a horde of immigrant insects escaping from a neighboring flat.

Many other species of insects live in urban centers, parks, streets, and riverfront areas. Most of these species are adapted to living just about anywhere. I shall not list every insect species you may find in your urban environment. Instead, as in the other chapters, I shall discuss some of the more prevalent groups and some specific species.

SPIDERS

The phylum Arthropoda contains more species than any other phylum. Probably on the order of 80 percent of all animals are members of this group. Insects are arthropods, as are the crustaceans, which include crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and their relatives. The other major class in this phylum is Arachnida, which includes the spiders, scorpions, ticks, and mites. People regularly encounter some of these species in cities. This section concerns those arachnids that people tend to find in and around their homes.

Probably the best-known spider is the daddy-long-legs, which looks like a spider with elongate, stiltlike, spindly legs. Some of these are true spiders in the family Pholcidae, while others are harvestmen, members of the family Phalangiidae. Both harvestmen and daddy-long-legs have small, rounded, compact bodies surrounded by extremely long, thin legs. Don’t worry if you have trouble distinguishing between these look-alikes. Few people can tell them apart. Generally, daddy-long-legs aren’t nearly as abundant indoors as they are outside, but because they are so distinctive, people notice them and know their name. More than 100 of these very similar species are found across North America.

Another group of spiders that urban dwellers all know is the family of comb-footed spiders, also called cobweb weavers, members of the family Theridiidae. This is a large, varied group with more than 1,500 described species, more than 200 of them found in North America north of Mexico. One of these species, the American house spider (Achaearanea tepidariorum ), is often responsible for spinning the silky cobwebs people are accustomed to finding in their homes. This spider is only about  inch (8 mm) in length, and is distinguished by streaks and patches of tan and darker brown on the sides of its spherical abdomen. Members of the cobweb weaver family are often found hanging upside down in their irregularly shaped webs. Two other genera in this family, Theridion and Steatoda, have members that cohabit with their human hosts. These spiders are called comb-footed because the last segment of their fourth leg is equipped with fine comblike bristles, used to draw silk from their spinnerets when encasing their prey.

inch (8 mm) in length, and is distinguished by streaks and patches of tan and darker brown on the sides of its spherical abdomen. Members of the cobweb weaver family are often found hanging upside down in their irregularly shaped webs. Two other genera in this family, Theridion and Steatoda, have members that cohabit with their human hosts. These spiders are called comb-footed because the last segment of their fourth leg is equipped with fine comblike bristles, used to draw silk from their spinnerets when encasing their prey.

Among the many groups with a spherical abdomen is the genus Latrodectus, or the widows. Of the cobweb weavers, these are the largest and probably the best known. All the widows are poisonous, although only the females bite. They are distinguished by an orange or reddish hourglass shape under their otherwise dark abdomen. The black widow (Latrodectus mactans) is found in warmer areas all around the world, but populations extend much farther north than most people realize. One congener—or species in the same genus—Latrodectus curacaviensis, the northern black widow, is found all the way from southern Argentina to southern Canada. Another similar species, the northern widow (Latrodectus variolus), ranges from northern Florida to southern Canada. This spider has the distinct hourglass, but it is usually broken into two parts. The northern black widow is often confused with the common black widow. Male common black widows are much smaller than the females, which are readily distinguished by that unmistakable hourglass marking underneath the abdomen. Of these species, the venom of the black widow is believed to be the most virulent. However, testing the virulence of any of the lesser known species is a task for which few people volunteer.

In North America the black widow spider ranges from Florida to Massachusetts, and west to Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Because they are most common in the South, that’s where most of the bites are reported. But in spite of its reputation, this is not a very bold spider. They usually retreat rather than stand their ground, unless guarding an egg mass. This is the job of the female, since after mating she usually eats the male, ergo the name “widow.”

The greatest number of black widows I ever saw in one place was in an otherwise fine restaurant in downtown Veracruz, Mexico. While waiting for my meal to be served, I got up to look at the view out over the water, where several people had been eaten by sharks, and I noticed cobwebs in the windows. Looking more closely I found a female black widow guarding an egg mass in each of the many corners.

Several similar species of brown spiders (family Loxoscelidae) in the genus Loxosceles are found throughout the southern United States. Many of these spiders may be poisonous, but few live in close contact with people, except for the brown recluse (Loxosceles reclusa). Most of these spiders are only about ½ inch (12 mm) long. Their coloration is dull, and their web is a nondescript sheet of sticky silk that doesn’t have any distinguishing characteristics. The brown recluse is found all through the south central United States, where it commonly lives in houses and comes out after dark. People rarely know they have them in their homes until someone is bitten. Dr. John Scherr, a physician in Atlanta, Georgia, reports that the majority of brown recluse bites occur in the garage or basement, areas that are usually dark, where there are spider webs. He says that the venom of the brown recluse is quite virulent to some people, and the painful bite can inflict a wound that sometimes stays open for weeks, occasionally even months.

The family Argiopidae, also known as the Araneidae, or orb weavers, range in size from  inch to larger than 2 inches (5 mm to 52 mm). They have a large abdomen in relation to their overall size, and their legs are strongly curved. The orb weaver constructs a vertical orb web with many concentric rings and a series of radii. In the center of the web is usually a series of zigzags, and the spider is generally nearby, waiting motionlessly, in a head-down position. Spiders in this family typically weave their vertical webs outdoors in vegetation, which is why some are known as garden spiders. Another genus in this family, Araneus, has more than 1,500 described species, and they occur all over the world.

inch to larger than 2 inches (5 mm to 52 mm). They have a large abdomen in relation to their overall size, and their legs are strongly curved. The orb weaver constructs a vertical orb web with many concentric rings and a series of radii. In the center of the web is usually a series of zigzags, and the spider is generally nearby, waiting motionlessly, in a head-down position. Spiders in this family typically weave their vertical webs outdoors in vegetation, which is why some are known as garden spiders. Another genus in this family, Araneus, has more than 1,500 described species, and they occur all over the world.

CENTIPEDES

Another class of invertebrates, the Chilopoda, or centipedes, are distinguished by flat, long, wormlike bodies with fifteen or more pairs of legs. Each body segment has just one pair of legs, unlike the millipedes (class Diplopoda), which have two pairs of legs per body segment. (All the members of the class Insecta have three body segments and a total of six legs.)

Centipedes are usually found in soil and debris, as well as under rocks and logs. There are many additional species that live in a wide range of habitats. On the first body segment just behind the head they all have appendages that look like little pincers. With these organs they insert a poison when piercing their prey. The bite of some species of centipedes can be extremely painful to humans. The house centipede (Scutigera coleoptrata) that commonly occurs in homes and apartments in the eastern United States and Canada, however, is harmless, or usually harmless. The house centipede is a member of the family Scutigeridae. Unlike most other centipede families, this has long legs and a very distinctive movement.

There are no records of scutigerids ever having bitten anyone when not provoked. The only records of bites come from people who were handling them, which is neither easy nor pleasant. You have only to touch these centipedes and their legs start to fall off. We do not know whether this is an evolutionary strategy that has helped protect them, similar to the slippery scales or hairs covering silverfish, or the tails of some species of salamanders and lizards that break off when you grab them. It could just be that these animals are amazingly fragile. Since they live in dark places where they are seldom seen, their fragility may not matter very often.

Centipedes are more common in the southern parts of the country, but with central heating, populations have been known to thrive farther north, and they are now found in buildings everywhere, usually in damp areas like bathrooms and basements. Their numbers never reach the point where they pose much of a problem. Their diet consists of small insects, such as flies and moths, so if you find any in your home, it is probably best to leave them alone. An older, well-fed centipede may reach a length ranging from 1 to 3 inches (2.5 to 7.6 cm); at that size they will even eat large roaches.

SILVERFISH

Some of today’s insects are thought to be early, primitive offshoots from the main stock. One such group is known as the Thysanura, or bristletails. Members of this wingless order of insects are somewhat different from most other wingless insects in that their lack of wings is thought to be primitive. They aren’t insects that previously had wings and lost them due to evolutionary changes. Rather they evolved and became established before any predecessors had wings—in other words, during a time when insect wings did not yet exist. This group is even more ancient than the cockroaches, with a fossil record dating back well over 300 million years.

Another characteristic that sets this group apart from most other insects is that the adults look like the young. They are known as bristletails because most have two or three long, thin, jointed appendages, like bristles, at the rear of the body. Their antennae are long, and some species have leglike structures on segments of the abdomen, which is unique among living groups of insects.

There are not many species in this group, and the entire order contains only four families. One family, Lepismatidae, is the best known because it includes some domestic species that live in buildings throughout the United States. The most widely recognized species are probably the silverfish (Lepisma saccharina) and the firebrat (Thermobia domestica). These two insects feed on all types of starchy substances and can become pests. They have been known to damage libraries, being attracted to the starch in the book bindings and labels. Starched clothing, linens, curtains, silk, and the starch in wallpaper glue all provide nourishment to these organisms. In grocery stores they will prey on any foods that contain starch.

The name silverfish was undoubtedly suggested by the tiny scales or hairs that cover the body of this insect, giving it a shiny, fishlike appearance. Silverfish are silvery white with a yellowish sheen around the antennae and legs. Lengths may vary, but they are usually less than ½ inch long (8 to 12 mm).

Firebrats resemble silverfish except that they have darker markings on the upper surface, and they are more common in warm spots around the home, especially near stoves, fireplaces, and furnaces. The firebrat has also been called the asbestos bug because it feeds on the sizing in asbestos insulation, which was used to insulate hot water and steam pipes before it was learned that asbestos is carcinogenic.

Both the silverfish and the firebrat move around in the dark and, when startled, can move very rapidly. Because of the scales on their soft bodies, when you attempt to catch them, it’s not at all unusual for them to slide right under your fingers, leaving a film of scales behind.

Should either of these species become a problem, methoxychlor, propoxur, Diazinon®, or Malathion® can be applied to cracks or places where the animals go. Since such pesticides aren’t always as safe as the labels claim, they should not be used unless your silverfish or firebrats have become really destructive.

DRAGONFLIES

The dragonflies and damselflies are insects in the order Odonata. There are thousands of species worldwide. They have two pairs of long, thin, membranous, many-veined wings. Their relatively large heads easily pivot in all directions, being flexibly connected to their long, slender bodies. With their large eyes and rotary head movement, they seem to be constantly aware of everything going on around them. Most are rather large, usually 1 to 5 inches (2.5 to 12.7 cm) long. Their antennae are very short and inconspicuous.

Dragonfly flight is currently being studied by aeronautical engineers at the University of Colorado, where it has been learned that a dragonfly generates lift amounting to seven times its body weight. Airplanes at their best generate only 1.3 times their weight in lift.

Among the superfamily Aeshnoidea, the family of darners, Aesh-nidae includes some species found around ponds and lakes in urban areas. The darners are the largest dragonflies in North America; most are 2¼ to 3¼ inches long (6.4 to 8.3 cm). They are strong and fast in flight, and are almost impossible to catch—unless you know that a startled dragonfly almost always shoots forward, up and away at a 45° angle. All one needs to do is hold a butterfly net in front of the insect, startle it, and it will fly into the net.

One relatively common dragonfly is the green darner (Anax junius). The males have a blue abdomen and no markings on the wings, with a greenish thorax. The females differ slightly; their abdomens are greenish violet and, when in a certain light, their wings are a faint golden color. These dragonflies are migratory and at times during the late summer and early autumn are seen congregating in large numbers.

Dragonfly

Species of dragonflies that migrate are known around the world, though where they’re migrating isn’t always clear. One common species regularly migrates up and down the Nile. Some species have been observed grouping together by the millions, and certain species travel as much as several hundred miles. Most of the well-documented migrations have been recorded in Europe and Africa.

In the superfamily Libelluloidea, or the skimmers, is the family Libellulidae, the common skimmers. This family includes several of the brightly colored and distinctly marked dragonflies commonly found near urban ponds. Many of these skimmers are fast and strong in flight and like other dragonflies, they are often seen stopping in midflight to hover momentarily. The eastern United States has four especially common species in this family. All are found near ponds in urban, suburban, and rural areas.

One widely recognized species is the white-tailed dragonfly (Plathemis lydia). They measure from 1 to 2 inches (4 to 5.2 cm) from the head to the end of the abdomen, with a wingspan of 2½ to 3 inches (3.8 to 7.6 cm). The males have a striking white abdomen, with a broad dark band toward the end of each of the four wings with four smaller markings closer to the abdomen, on each of the wings. The female doesn’t have any white on the abdomen. Of all the dragonflies studied, this one copulates the fastest, usually lasting 30 seconds, while 5 minutes is more common for other species.

to 2 inches (4 to 5.2 cm) from the head to the end of the abdomen, with a wingspan of 2½ to 3 inches (3.8 to 7.6 cm). The males have a striking white abdomen, with a broad dark band toward the end of each of the four wings with four smaller markings closer to the abdomen, on each of the wings. The female doesn’t have any white on the abdomen. Of all the dragonflies studied, this one copulates the fastest, usually lasting 30 seconds, while 5 minutes is more common for other species.

A smaller species that is frequently encountered in urban parks is the common amberwing (Perithemis tenera). It is a little more than an inch (about 3 cm) long from the head to the end of its abdomen, with a wingspan of about 1½ inches (3.8 cm). The wings are amber in the male while they are clear with brown spots in the female.

Another common species found around ponds throughout the eastern, central, and southern states is the blue pirate (Pachydiplax longipennis ). The wings are often tinged with a light brown, and the female’s body is usually brown with yellow markings, while the males develop a blue body after emerging. This developmental color change observed among the males of some species is known as pruinosity. The same process is involved with male white-tailed dragonflies when they develop their white abdomen. As the males of some species get their full colors, a substance emerges through the integument, which accounts for the whitish or bluish markings that appear. The substance looks powdery and feels greasy, and will come off if you rub it. Little is known about either the process or the structure. Recently it has been suggested that the function of the pruinosed colors could be related to vision in the ultraviolet spectrum, because most pruinosity is quite distinct in the ultraviolet.

The green-jacket skimmer (Erythemis simplicicollis) is another common species that is often found near ponds in urban parks. These dragonflies have a green face, and the females have a black and green body. The males are only black and green when young, and later pruinose to a blue or green that is significantly different from the green color of the female. The wings don’t have any markings. The reason most of these dragonflies are found near ponds is because the males select a site where they wait for a female to come in. After mating, the female lays eggs, and then she leaves. Because the males stay and wait while the females come in, accomplish their reproductive functions, and leave to feed elsewhere, 95 percent of the dragonflies found near ponds are usually males.

Another family well represented in urban environments is the Coenagrionidae, or the narrow-winged damselflies, which includes many genera and species that live in a variety of habitats. Most are weak fliers and, unlike the other families already mentioned, when damselflies land on something, they usually hold their wings up over the body rather than out flat. The sexes are differently colored among most of the species, the males being brighter. The family comprises the bluets, which are usually light blue with some black markings, though some are bright orange or bright red. Enallagma is the largest genus in the family, with 38 species in the United States. They are usually found around ponds, with several species occurring in suburbs as well as cities. An abundant form in the eastern United States is the common forktail (Ischnura verticalis). The males are dark with green stripes on the thorax and blue at the rear tip of the abdomen. Most of the females are bluish green, though some are brownish orange, and still others look more like the males.

Next to mosquitoes, dragonflies and damselflies are probably the best-known insects having aquatic larval stages. Their nymphs, or naiads, known to some as perch bugs, are drab colored, usually brown, and somewhat bizarre looking. They live on the bottom of ponds, lakes, streams, or rivers, usually among the muck and vegetation. They are not common in fast-moving or polluted waters. Many city parks have ponds, and these habitats have proved suitable for several species.

Odonate nymphs are carnivorous, eating aquatic insects, annelids, small crustacea, and mollusks. The very small nymphs eat protozoa. The entire life cycle takes about one year in most species, though many have aquatic stages that overwinter, extending the life cycle to two years. When the nymphs are ready to be transformed into adults, they crawl out of the water, usually onto some vegetation or onto the shore. Their exoskeleton, the supporting structure covering the outside of the body, then splits down the back, and the adult slowly works its way out. Before it can fly off, it has to remain still for about an hour until the wings dry and stiffen.

The adults are often seen mating, and the females may be seen flying near the surface of the water, touching it with her abdomen periodically as she scatters her eggs. Some species deposit their eggs on the surface of the water; others put them in floating mats of algae or in the sand, mud, or vegetation along the water’s edge. All damselflies and some true dragonflies cut holes in submerged plant stems with their specialized egg-laying apparatus, their ovipositor, and then insert their eggs. If you watch carefully, you can see these insects catching smaller insects with their feet while in flight and then transferring the prey to their mouths. To see this the light has to be perfect.

Fossils show there were dragonflies with wingspans of several feet, but the evolution of avian predators that were able to chase them down may have eliminated opportunities for all the larger odonates, forcing them to survive in the niches available for smaller odonates, where they continue to do remarkably well.

Dragonflies and damselflies recently were the center of a controversy in New York City. The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation planned to drain Belvedere Lake in Central Park, dredge the bottom, and rebuild much of the shoreline. What hadn’t been considered was the effect this would have on the nineteen species of dragonflies known to occur there. There are many species of damselflies at Belvedere Lake, too, but they have yet to be properly identifed. While there are hundreds of odonate species across the country, to find this many doing well in the middle of Manhattan is significant. In response to pressures from conservationists, environmentalists, and organizations like the Audubon Society, the Parks Department is assessing its options with regard to potential alternatives without adversely affecting the dragonflies there.

CRICKETS

The cricket family, Gryllidae, is a member of the insect order Orthoptera, which also contains the grasshoppers, walking sticks, mantids, cockroaches, and katydids. Worldwide there are over 900 described species of crickets. Their hind legs, like the grasshopper’s, are built for jumping. The antennae are long and thin; most forms are winged. The front wings are usually long, narrow, and somewhat thickened, while the hind wings are membranous, broad, and have many veins. When the cricket is not flying, its hind wings are usually folded like a fan underneath the front wings.

Cricket

Katydid

Crickets are probably best known for the sounds they produce, primarily by rubbing one part of their body against another. This process is called stridulation. Gryllids rub the sharp edge at one end of a front wing along a filelike ridge underneath the other front wing. Both front wings have a file and a scraper. When the song is produced, the front wings are elevated and can be seen moving back and forth. The sounds made are usually species-specific—that is, each species produces a distinctive sound. Recently it has been shown that some species, which were previously thought to be undifferentiated, actually differ with regard to when they make their sounds rather than by what the call sounds like. The calls are usually delivered as pulses, often produced at a regular rate. They sound like a trill, a buzz, or a chirp. Some female Orthopterans make sounds, but sound production is primarily a function of the males, who do it to attract females.

A gryllid subfamily known as the Gryllinae contains the house and field crickets. They are usually over ½ inch (1.3 cm) in length, and they vary in color from brown to black. These crickets are common in fields, along roadsides, in lawns, and sometimes in homes. One of the most abundant species in the East is the northern field cricket (Gryllus pennsylvanicus ). The house cricket (Acheta domesticus), an Old World species that was introduced into this country from Europe, was initially reported in New York State during the first quarter of the 19th century, and it subsequently spread rapidly. It could be that people helped move these crickets around because when they first arrived they were something of a novelty; their chirping was thought to be cheerful. They are now widely distributed throughout the United States.

Each year from mid-September to early October, a species of cricket becomes quite a nuisance in Austin, Texas, where the insects gather in hordes. Each morning masses of crickets are found next to the state capitol, where they seem to be attracted to the illuminated dome. They enter the building through any hole and can be found everywhere. When they die, their smell is awful, and they create a considerable maintenance problem; spraying apparently has no effect on these insects. The solution to Austin’s cricket problem seems simple: turn off the dome lights in September.

COCKROACHES

The insect order Orthoptera includes cockroaches in addition to grasshoppers, crickets, mantids, and walking sticks. Some taxonomists—scientists who classify organisms into groups and categories—place all the cockroaches in the suborder Blattaria, which other taxonomists call Blattodea, or Blattoidea. The most widely recognized family in this suborder is Blattidae.

Worldwide there may be about 3,500 species, most of them found in the tropics. It is now believed by most experts that all cockroaches are native to Africa, and have been inadvertently introduced around the world. In the United States, at last count there were 56 species, most of which are found in the South. Several species represent those that most people see, the ones that are household pests. Cockroaches carry some pathogens, and it has been demonstrated that they can transmit food poisoning, but for the most part they do not spread much disease.

As a group, the cockroaches are identified by their flattened, oval shape and downturned, concealed head, which is usually underneath the large front section known as the pronotum. These insects have long, thin antennae, and some species have well-developed wings. They eat a wide range of food, including dead animals, and the more domestic species eat food left around the kitchen. Their eggs are enclosed in a capsule.

Cockroaches prefer to come out in the dark, so when you walk into the kitchen at night and turn on the lights, you find out how much of a roach problem you have. These insects breed quickly and do well where they can scavenge the small amounts of food left around the stove, kitchen table, floor, sink, and waste basket.

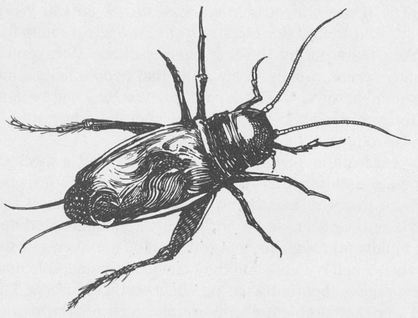

American cockroach

The smallest of the household species is the German cockroach (Blatella germanica), which is ½ to ¾ inch (13 to 20 mm) long. Actually a native of northwest Africa, it is also found throughout Europe and parts of Asia. This roach is light brown with two darker longitudinal stripes on the pronotum. The female carries her egg case until the eggs are almost ready to hatch. If you kill a roach carrying an egg case, make sure you squash the egg case as well. German cockroaches are commonly found in kitchens. In the North, they appear to pass through about three generations a year.

In the eastern United States, some people still refer to the German cockroach as the Croton bug, or water bug. These names were coined during the 1840s when huge water pipes were constructed to bring water from the Croton reservoir to New York City. The pipes served as a route of dispersal for the roaches. Croton was the first town in America where these insects were found, and they rapidly spread when the Croton aqueduct was completed in 1842. In Germany these insects are called Russian cockroaches, but in the Soviet Union they are called South European roaches. No one seems to want to accept responsibility for the origin of this invertebrate.

The larger American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) is 1¼ to 1½ inches (32 to 38 mm) long. Adults are darker and more reddish than the smaller German cockroach, with a yellowish band around the margin of the pronotum. They are more often found in warm basements of city buildings than in kitchens. It is widely believed that this cockroach originally came to North America from tropical Africa with the slave trade.

The Oriental roach (Blatta orientalis) is a relatively large, dark brown roach, normally about ¾ inch (20 to 25 mm) long. For many years people thought it was native to North America. Early writings were interpreted to mean that this insect was already a problem shortly after the Pilgrims arrived on the Mayflower. Actually, without precise descriptions, it is impossible to be sure what insects were encountered. It is more likely that this roach traveled from Africa to Asia to Europe and then to North America, arriving after the Pilgrims came here. The Oriental cockroach is now found in many of our northern cities, though it is most abundant in central and southern cities.

The brown-banded cockroach (Supella longipalpa), also known as the tropical cockroach, is light brown with mottling. The females have reddish brown wings, while the males’ wings are lighter. The adults are only about ½ inch (13 mm) long. Though more common in the South, they are found in the northern regions of the country as well, surviving in heated buildings where they usually live near kitchens and bathrooms.

There are many other cockroach species in the country, though none as widespread as the species mentioned above. Most of the species that have become household pests are found almost exclusively in densely populated areas. What may be the most recent roach arrival to join North America’s growing cockroach fauna is the flying Asian cockroach (Blatella asiana). Though currently restricted to the Tampa, Florida, area, there are fears that within a matter of years, they may spread throughout much of the East Coast and, with few restrictions, they could continue their city hopping aboard trucks and cars right across the continent.

One way to control cockroaches is to eliminate most of their food supply. Without food, they will move elsewhere. If you kill every roach you see, over time you can amount to a formidable predator. But this method will work only if your population is small enough to deal with. Centipedes, mice, rats, and cats will also prey on your roaches. If, however, your population is so large that you and your household pests and pets cannot put a dent in the overall numbers, you can use chemicals. One of the least expensive and most effective is boric acid, which can be bought as a powder in most drug stores. Boric acid is toxic and it should be used appropriately. Sprinkle the white powder in places where the insects are likely to walk—behind the sink, for example, because they go there to get water, under the waste basket, along the floor against the wall, near holes in the floor and wall, behind the stove, and along the base of the refrigerator. The roaches will walk through the boric acid and get it on their bodies. Later, when grooming themselves, they will ingest the powder, which will kill them. Many commercial roach traps and poisons are available. The insecticides Baygon®, chlorpyrifos, Diazinon®, malathion, and resmethrin are also effective. Spray the chemical along baseboards, under cupboards, under the kitchen sink, in the bathroom, and in other warm, moist places. Don’t apply these chemicals everywhere, only in places where you know the roaches hide.

No matter how many chemicals you use, if you don’t cut off the roaches’ food supply, you may be in for a long fight. Some people go so far as to rinse out cans and bottles before throwing them in the trash, and they carefully wrap all edible garbage before throwing it out in order to reduce the amount of food available to cockroaches. I even know a woman who puts her garbage in the refrigerator to keep it away from the roaches. I’d say she’s taken the fight a step too far. In the aggregate, these techniques will keep your roach problem down to a minimum. But if your neighbors harbor large roach populations, you will always have the insects migrating into your apartment, so constant vigilance will be necessary.

TERMITES

Termites feed on organic matter and sometimes completely destroy wood and books. These colonial insects—insects that live together in colonies—are in the order Isoptera. Termite colonies contain both winged and wingless forms. Their bodies are usually whitish, but the winged adults are sometimes brown or black. This order has about 2,000 described species, most of which are tropical. About 40 species occur in the United States.

Termites, sometimes called white ants, look something like ants, though the two groups are not closely related. They differ in that termites are soft-bodied and usually light-colored. In the winged forms, the front and hind wings of termites are the same size and with the same venation—that is, the same pattern of veins—while the front wings of ants are larger and have more veins than the hind wings. The termite’s abdomen broadly meets the thorax, whereas the ant’s abdomen is constructed at the base and is joined to the thorax by a narrow petiole, or stem. Many other characteristics differentiate the two groups, including differences in the antennae and the caste systems.

Some termites live in dry areas above ground, and others live in moist, underground habitats. The termites that live in moist areas eat wood that is buried or in contact with the soil. In San Francisco, where the climate is humid and temperate for much of the year, a considerable termite problem has resulted in a building code that does not allow any new buildings to be constructed with wood touching the ground.

In the United States, most termite species eat dead wood. This is largely composed of the complex carbohydrate, cellulose, which becomes nutritious when broken down in the termite’s gut. With the aid of single-celled, flagellated protozoans in the order Hypermastigida, which live in the termite’s digestive tract, these insects are able to digest wood. Some termites have bacteria, rather than protozoa, that break down cellulose. Without either of these symbiotic microorganisms, termites would starve to death.

In the tropics, many species of termites build large, exposed nests constructed from termite excrement, soil, and chewed-up wood. American species, however, build small, narrow tunnels right through wood and construct covered passages that protect them from light and the desiccating effects of the air. The most common termite species in the United States, the one that causes the greatest amount of damage, is Reticulitermes flavipes.

The best way to avoid a termite problem is to be sure that your building has no wood that comes in contact with the ground. All wood should be at least 18 inches (45 cm) above the ground. Foundations should be sealed, and any cracks that form over the years should be patched. Expansion joints used to be filled with coal-tar pitch, and the wood was treated with coal-tar creosote, the same material that was used to treat telephone poles, for the same reason. But now many of the more susceptible construction materials are pretreated with termiticides as a preventive measure.

Once termites have infested a building, controlling them can be a long, expensive battle. When possible, the colony should be located and dug up, and all the adults, larvae, and eggs should be killed or removed. It used to be that the walls containing the termites’ tunnels and the covered passages were scraped and treated with creosote. The wood containing the termites was removed and replaced with metal or cement, even if this meant replacing timbers in the main frame. The remaining, unaffected wood was treated with creosote, and, when possible, cement or metal was inserted between the ground and any wooden parts of the structure.

Such measures were complicated and expensive, and this was not a do-it-yourself job. Now, exterminators use strong insecticides that are not available to consumers because they are so dangerous. When you discover a termite problem, it is always prudent to hire an exterminator; waiting can only prove more costly. Hiring a reputable exterminator can also be important because when certain insecticides are applied incorrectly, the fumes may persist for years, creating a potentially hazardous situation.

Termite infestation occurs most often in humid, temperate areas that do not generally have severe winters, but the drier, more northern cities are not immune to such damage. Just recently, for example, in New York City, I inspected a brownstone that was being renovated. Its main beams revealed considerable termite damage, so they were all removed and replaced with metal beams.

BOOK LICE

Psocoptera represent an order of more than 1,000 species of small, soft-bodied insects. The United States has some 40 genera and nearly 150 species. Virtually no one has heard of any of them, and fewer people have ever seen any. Many species in this group live outdoors and have well-developed wings. Those that live indoors are usually wingless and are found in association with old papers and books—ergo, their name, book lice. Despite the name, however, they aren’t related to the true lice, which are all members of Anoplura, another order of insects. Unlike true lice, book lice aren’t parasitic, and few look louselike.

Trogiidae and Liposcelidae are families of book lice most commonly found indoors. The two groups are differentiated by the thickness of the femora in their hind legs; the trogiids’ hind femora are more slender than those of the liposcelids. Psocopterans feed on fungi, such as molds and mildew, as well as on starch granules, pollen, and dead insects. If book lice are present, you can see them when you open old books or papers, if you search carefully. Look for a tiny, translucent, creamy or yellowish insect rapidly moving across the page. These insects are only about a millimeter long, so you will need a magnifying glass to see that they have six legs, no wings, a well-developed head with chewing mouth parts, small compound eyes, and very thin antennae that are about one-half as long as the entire body.

Don’t be fooled into believing that book lice won’t cause much damage because they are so small. Part of my library was once damaged in a flood that left considerable fungal growth on the books. The growth of this mildew was arrested when the books were dried out, but it was at this point that I noticed all the book lice. They had probably been there all along, but the population increased considerably with the new availability of mildew, which they were feeding on. People who purchase a lot of old books have a good chance of bringing book lice into their home. The book lice eat the fungi in old books, and they probably feed on the sizing in the paper and on the paste that holds the bindings together as well, particularly older bindings. Although they do only a small amount of harm at one time, over the years they can damage an entire collection.

Book lice are difficult to eliminate. Prolonged heat and dry air will usually decrease the size of the population, but it isn’t always easy to apply this type of treatment to an entire library. Dusting or spraying a library with pesticides such as pyrethrin or malathion can also be effective. When properly applied, fumigants penetrate all porous materials, including wood and books. The best advice I can give is to keep your books in a dry, well-ventilated area. If you have book lice that you find difficult to live with, spring for a proper fumigation.

There is one other elimination method available that has been used successfully with the next group of pests, that may work with book lice. Some libraries, particularly rare book libraries, have purchased special freezers in which books are placed and left until all the eggs and insects have died.

BOOKWORMS, GRAIN BEETLES, AND MEALWORMS

The insects that eat through books and can cause considerable damage to libraries are often known as bookworms. The species that actually eat right through the pages, leaving behind nasty little tunnels, represent any of several species of bread beetles or furniture beetles. The adult beetles are usually small and dark, reaching a length of less than a quarter of an inch (6 mm).

The bread beetle that has been called the bookworm was originally a grain feeder; it will eat ground grain anywhere it is available. Having invaded a place where grain is stored, such as a warehouse or bakery, the adult beetle will eventually lay its eggs on the premises. During earlier times, when people kept grain and flour in and near their homes, these beetles presented a serious problem. If they laid their eggs on old books, the larvae would hatch and then eat through the pages. Eventually the fat grub, which is also quite small, rarely larger than the adult beetle, would pupate, metamorphose into an adult beetle, eat its way out of the book, and continue its life cycle. Luckily bookworm tunnels are seldom seen anymore.

Occasionally people still find grubs or beetles in their flour, cereal, dried fruit or vegetables, shelled nuts, chocolate, spices, candies, pet food, or birdseed. Infestation can occur in a warehouse, in transit, on a grocer’s shelf, or in your home. You may discover the insects when you open a package of flour or when you see small brown or black beetles, or their larvae or pupae, in a cupboard near stored grain products. But very few products are purchased containing beetles any longer because most grain is treated with chemicals that eliminate insect problems. Also, products are packaged so well that few can become contaminated with insects during transit or while sitting on the grocer’s shelves. Although the tendency may still be to blame the store or the manufacturer, in most cases the source of the beetle infestation is the home.

Twenty-five or more different species of insects are found from time to time in grain products used in the home. I will describe several of the most common species. The smallest is the saw-toothed grain beetle (Oryzaephilus surinamensis), which is only about  inch (2.5 mm) long. Its name comes from the ridges, or teeth, on either side of its thorax. This species is distributed worldwide. A very similar beetle in size, shape, and habits is the square-necked grain beetle (Cathartus quadricollis), which is found in the southern states.

inch (2.5 mm) long. Its name comes from the ridges, or teeth, on either side of its thorax. This species is distributed worldwide. A very similar beetle in size, shape, and habits is the square-necked grain beetle (Cathartus quadricollis), which is found in the southern states.

Probably the most common flour beetle is the confused flour beetle (Tribolium confusum), generally known among millers as the bran bug; it is only  to

to  inch (3 to 5 mm) long. This small, hard-shelled, dark brown beetle is the most serious flour pest in North America. It is more abundant in the temperate regions. The red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) is similar in size and shape and is usually reddish brown. It is common in the southern states. The key to telling these two species apart is the arrangement of the antennal segments. The antennae of the confused flour beetle gradually increase in size until they are much thicker at the outer ends than at the roots. In the red flour beetle, however, the outer segments of the antennae abruptly become markedly thicker than the inner segments.

inch (3 to 5 mm) long. This small, hard-shelled, dark brown beetle is the most serious flour pest in North America. It is more abundant in the temperate regions. The red flour beetle (Tribolium castaneum) is similar in size and shape and is usually reddish brown. It is common in the southern states. The key to telling these two species apart is the arrangement of the antennal segments. The antennae of the confused flour beetle gradually increase in size until they are much thicker at the outer ends than at the roots. In the red flour beetle, however, the outer segments of the antennae abruptly become markedly thicker than the inner segments.

Two species of mealworms are found in grain products around the world. They are the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) and the dark mealworm (Tenebrio obscurus). Both are considerably larger than the grain beetles described above. Mealworm adults are usually slightly more than ½ inch (13 to 17 mm) long. Adult yellow mealworms are reddish brown, while adult dark mealworms tend to be black. The larvae of both species are raised as food for captive animals and can be purchased in pet shops. Both species do well in a box containing oatmeal and a potato, or some other source of moisture. The larvae of these species, when just hatched from the eggs, are barely visible to the naked eye. The tiny, creamy yellow worms feed on grain and flour for a week or two until they pupate, then the adults lay hundreds of eggs and live a few years.

The best way to eliminate grain beetles and mealworms is to destroy all infested products. Store uninfested products in glass jars with tight-fitting lids. There may be unhatched eggs in some fresh products, so check the jars later and throw the grain away if you find any larvae. Thoroughly clean the infested area of your cupboard, including cracks and corners where small amounts of flour tend to accumulate. Treat the cupboard with the household formulation of malathion, known as Cythion®, or with Diazinon® or pyrethrin and piperonyl butoxide, using a paintbrush or spray can. Do not allow any of these chemicals to touch your food or utensils. Once the chemicals have thoroughly dried, cover the area with clean shelf paper, and then put everything back on the shelf. If the beetles reappear, you’ll know that either the last cleaning was inadequate or you have bought another infested package. To avoid infestations, purchase smaller amounts of meal and flour products in tightly wrapped packages.

WATER BUGS

Lay people use the word “bug” to denote many species of insects. Entomologists, however, use this word only for hemipterans, the true bugs. All members of the order Hemiptera have piercing-sucking mouthparts that form a narrow beak, and the various water bugs discussed in this chapter fall into this order. A reminder, however, at the outset: cockroaches are sometimes referred to as water bugs because they are found near pipes and faucets, but they are unrelated to the true water bugs and were discussed earlier in this chapter.

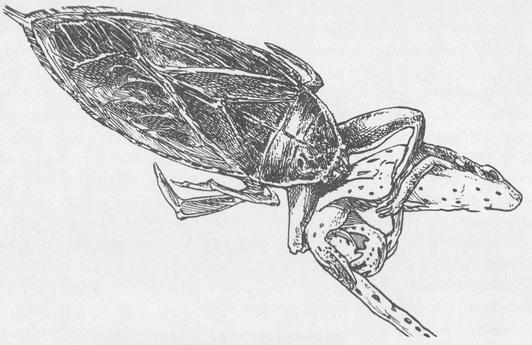

Giant waterbug eating a newt

Water boatmen, like all water bugs, are aquatic insects. These members of the Corixidae family have small, elongate, oval bodies with long hind legs that are oarlike. It takes an expert to distinguish the genera as well as the many very similar species. Most are only about ¼ to ½ inch (6 to 13 mm) long. They are grayish or brown; the upper surface usually has thin crossbands, and the two pairs of wings are concealed while the insect is in the water.

Most feed on algae and small aquatic invertebrates. Like other aquatic bugs, they don’t have gills and must come to the surface for air, though they will often take a bubble of air underwater and carry it under their wings or on the surface of the body. Water boatmen can be found in city ponds. Many other aquatic bugs bite when handled; this one cannot.

Another group of true bugs, the back swimmers, are members of the Notonectidae family. These bugs look very similar to the water boatmen except that they swim upside down—but, of course, they don’t think it’s upside down. Back swimmers feed on insects, tadpoles, and small fish. They will often attack prey considerably larger than themselves, from which they will suck the bodily juices with their sucking mouthparts. When handled, they can inflict a rather painful bite that feels like a bee sting. It seems that the pain is caused by the juices in their saliva, injected under the skin. There are two genera of back swimmers in the United States. The larger, more common species belongs to the genus Notonecta. Notonecta undulata is the species most often encountered.

The family of giant water bugs, the Belostomatidae, includes some of the largest members in the order Hemiptera. These insects reach a length of over 4 inches (10 cm), but in the United States few exceed 2½ inches (6.4 cm). They are brown, oval, and flattened; their wings are always tightly folded over their back when they are not flying. They readily leave the water and fly around, especially at night, when they are sometimes attracted to lights. Giant water bugs are frequently found in freshwater ponds and lakes where they feed on a wide range of insects, snails, tadpoles, small fish, and occasionally on salamanders, frogs, and even hatchling turtles. Be careful with these insects because they can inflict a painful bite. Three genera occur in the United States: Abedus, Belostoma, and Lethocerus, of which the latter two are more widely distributed. A giant water bug in the genus Lethocerus is illustrated on the previous page.

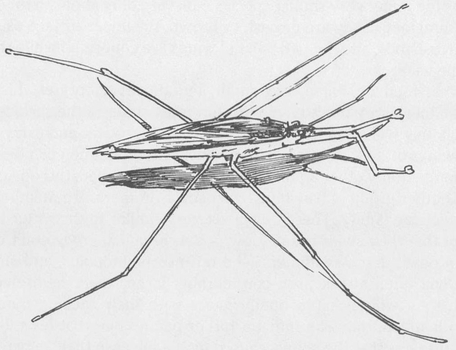

Water strider

Of all the water bugs, water striders are probably encountered most frequently. The family of water striders, Gerridae, consists of a group of slender-bodied, long-legged insects that skate about on the water’s surface where they feed on small insects, especially those that fall or get washed into the water and struggle at the surface to escape. Water striders have a dark brown body that is only about  to 1 inch (1.0 to 2.5 cm) long. Although they have three pairs of legs, because their front pair is short and the two succeeding pairs considerably longer, one might think they have only four legs. Water striders are usually found on calm waters, in coves, and protected areas where they are most likely to find struggling insects. Apparently responding to the ripples created by any small floating animal, they orient themselves and move toward their potential quarry. Water striders frequently are seen in city ponds. Winged and wingless forms occur in many species; the wings enable them to move from one isolated body of water to another. All the genera are restricted to fresh water, except one; its species all live on saltwater.

to 1 inch (1.0 to 2.5 cm) long. Although they have three pairs of legs, because their front pair is short and the two succeeding pairs considerably longer, one might think they have only four legs. Water striders are usually found on calm waters, in coves, and protected areas where they are most likely to find struggling insects. Apparently responding to the ripples created by any small floating animal, they orient themselves and move toward their potential quarry. Water striders frequently are seen in city ponds. Winged and wingless forms occur in many species; the wings enable them to move from one isolated body of water to another. All the genera are restricted to fresh water, except one; its species all live on saltwater.

BEDBUGS

Bedbugs are also true bugs in the order Hemiptera. They represent a relatively small family comprising only about 30 species worldwide, of which 8 species have been recorded in North America. They all feed by sucking the blood from birds and mammals. These flat, oval insects have tiny vestigial remnants of wings; they lost most of the structures after they took up a parasitic way of life. They are large enough to be seen quite easily, though when full-grown most are only  to ¼ inch (5 to 6 mm) long and about

to ¼ inch (5 to 6 mm) long and about  inch (3 mm) wide. Their color is usually a reddish brown.

inch (3 mm) wide. Their color is usually a reddish brown.

Some bedbugs feed only on the blood of bats. One such species is Cimex pilosellus. Other species (Oeciacus spp.) are found only on swallows and martins. Another species (Cimexopsis nyctalus) is restricted to chimney swifts. This is interesting, considering that although bats, swallows, martins, and chimney swifts are not related, most of them nest communally in dark, protected places, and all feed on aerial plankton or on insects in midair. In North and Central America, another species, Haematosiphon inodorus, is usually associated with chickens. One of the forms that feeds on humans is Cimex hemipterus, but this is a tropical species that is abundant chiefly in Africa and Asia.

The primary species that attacks humans in Europe and North America is Cimex lectularius, which is found around the world in temperate regions, having been carried everywhere that people have gone. Though it has long been well known in London and other major European seaports, the bedbug was not found in North America until the middle of the 17th century, when it was brought to New England by ship.

The thick, flat bodies of bedbugs allow them to hide deep in the cracks in wood, which was once used to make bed frames. It is here that they lay clusters of 50 to 200 small white eggs, which hatch about eight days later. The young are almost transparent, with a slightly yellowish tone. They moult, or shed their skin, five times before they reach adulthood. To grow they require warm blood, usually one meal between each moult. They are often found living in sleeping areas, typically in hiding places in the bed frames. They may also be found in other furniture, under loose wallpaper, or just about anywhere that they can hide. They feed only at night; each bug may feed only once a week or so, and they can live from four months to a whole year without ever having a meal. As a result, unoccupied houses and apartments can remain infested for long periods. When no people are around, bedbugs have been known to feed on mice or any other available mammals, which they seem to find, at least in part, by homing in on their warmth. Having once found an animal’s nest or place that it sleeps, bedbugs will continue to return each time they are hungry.

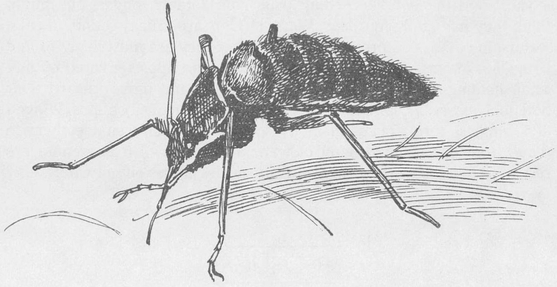

Bedbug

It takes a bedbug five to ten minutes to complete a meal. But since they suck blood during the night, usually shortly before dawn when people are in a deep sleep, their presence often goes unnoticed. They do not inject any irritating blood thinners like some other sanguivores, and many people are never aware that they have been bitten by bedbugs. On some people, however, the bitten area becomes itchy and inflamed. It is common for the large, red bedbug welts to last for days before going away. People who have been bitten by most household pests usually feel that bedbug bites are more irritating than those of fleas or lice. Unlike fleas and lice, bedbugs have never been shown to transmit diseases.

Bedbugs are thought to have originated in the Mediterranean region and subsequently to have spread their range. Some researchers suggest that bedbugs originally fed on bats, but turned to humans when they lived in caves.

For years people fought bedbugs by catching and killing them and by painting the bed frame, especially the joints and the cracks, with a mixture of oil and candleberry wax, or with bitterwood. Actually, just painting over all the cracks with turpentine or an oily substance will kill most of the bugs present. Usually a dusting with malathion or pyrethrum is quite effective, but be careful when using these substances because they are quite dangerous. Not everyone is so patient. The New Yorkers I have known who had bedbugs dealt with the problem by throwing out the furniture that was thought to be harboring the insects.

Bedbugs do not seem to be nearly as prevalent in the United States as they once were, which may be due to a combination of factors. Bed-frames are rarely made of wood anymore, so there are fewer cracks in which the bedbugs can hide, insecticides have proved quite effective in eliminating infestations, and it may be that the heat generated by radiators has proved far too confusing for the heat-seeking sensors that enable these insects to find their warm-blooded meals. Nevertheless, bedbugs are still found in most major cities, where people bring them home on old furniture and secondhand clothing. Many exterminators still advertise that they will kill termites, roaches, mice, rats, and bedbugs.

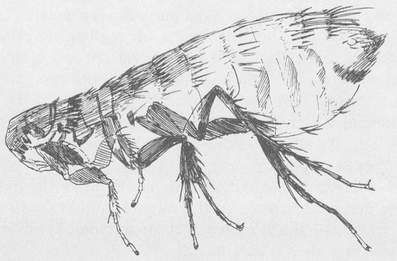

Flea

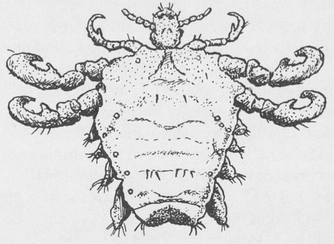

Crab louse

MONARCH BUTTERFLY

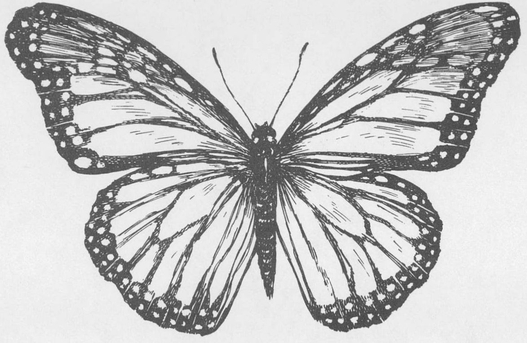

Because the unique life history of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) includes remarkable migrations, it passes through and settles in some urban areas. These large orange and black butterflies have a wingspan of 3.5 to 4 inches (8.9 to 10.2 cm). Monarchs are a member of the family Danaidae, and are known as the milkweed butterflies because each member of the family lays its eggs on milkweed plants (Asclepiadaceae), though some also lay their eggs on nightshade plants (Solanaceae). Monarch caterpillars feed on several species of milkweed (Asclepias spp.) and sometimes on dogbane (Apocynum spp.) and green milkweed (Acerates sp.). Danaids are distributed throughout the tropics and North America, where there is a vast supply of milkweeds. The monarch butterflies, like all danaids, evolved in the tropics, but they have developed a complex migratory behavior that brings them north in the spring through successive generations. Monarchs breed in the north, increasing their numbers throughout the summer, until the last generation begins to congregate toward the end of the summer. By mid-September their southern migration is well under way.

Monarch butterfly

Milkweed

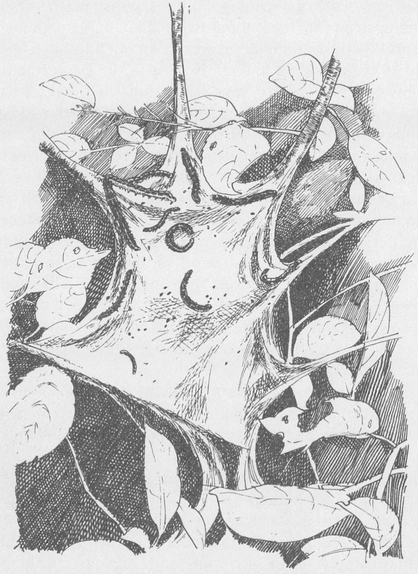

Monarch butterfly drying its wings shortly after emerging from its chrysalis

When fall approaches, the monarchs living east of the Rocky Mountains respond to the shorter, cooler days by flying south. When migration is in full swing, they can be seen gently wafting their way right through the cities that lie in their path, including midtown Manhattan. Once you become aware of their presence, you will notice monarchs floating through the air all during the autumn migration. Although several other butterflies, some moths, and numerous other insects also have mass migrations, nothing like the monarch’s journey is known. What makes these insects different is the way they settle in one spot by the millions and remain there for months. Most other species could be so vulnerable in such a situation that predators would rapidly wipe out the entire species. Monarchs, however, are not attractive to most predators. The extremely bitter and poisonous chemicals that the monarch caterpillars ingest when feeding on milkweed plants are passed on to the adult butterflies, imparting a terrible-tasting poison that protects them. Some animals have learned to ingest only the safe parts while discarding the rest of the monarch, but despite these pressures, most overwintering monarchs survive.

On their route back to the tropics, once they reach Texas and northern Mexico, they start laying down reserves of fat so that by the time they arrive at their overwintering sites in mid-November, they are 50 percent fat. They stay relatively dormant throughout the winter, becoming active only on warmer days when they fly off looking for water. In mid-March they head north again.

Some monarchs overwinter along the Florida coast and on islands in the Gulf of Mexico, but during severe winters they are all killed by heavy frosts. In the West, the monarchs fly to the coast and to the south as the weather gets colder. Each year they return to the same overwintering grounds along the California coast from San Francisco to Los Angeles. These areas include the groves of eucalyptus trees north of San Francisco, which are far enough from the ocean to be protected from the winter winds. Although there are many overwintering sites up and down the West Coast, the best known are the moist pine groves in Monterey County. Thousands of monarchs overwinter in the “butterfly trees” in the town of Pacific Grove, where they are protected by law. Their bright colors that advertise the acrid, poisonous chemicals laid down in their tissues do not protect these butterflies from the onslaught of human encroachment. Seven of the forty-five known sites where about 10 million monarchs overwintered along the California coast were recently destroyed by developers in just two years. It is essential to preserve the remaining overwintering sites and also the patches of milkweed on which the larvae feed. The Monarch Project, organized by a conservation group on the West Coast, is attempting to increase public awareness of the precarious situation faced by the monarchs in the hope that builders will avoid developing any site that could endanger monarch populations.

GYPSY MOTH AND TENT CATERPILLAR MOTH

The gypsy moth (Porthetria dispar) isn’t one of the major insects in urban areas, but it does have a significant impact on suburbs. Because of this, and also because the press periodically becomes obsessed with the species, it will be discussed here.

Gypsy moths weren’t found in North America until the late 19th century when a Harvard University researcher, Leopold Trouvelot, received a number of gypsy moth cocoons from a friend who had sent them from Europe. Trouvelot, who lived in Medford, Massachusetts, may have been interested in raising them for silk production. The project never took off, but the moths did. When the adults emerged from their cocoons, Trouvelot mounted a few and allowed the rest to escape. Unchecked by natural parasites and predators, they reproduced, and their numbers increased.

At first, no one noticed that the moths had become established in the woodlands near Medford. About twenty years later, however, the caterpillars had begun to cause considerable damage to foliage in the Boston area. By the late 1920s, gypsy moths had spread throughout the New England states and southeastern Canada, and there was a population in New Jersey. They continued their spread toward eastern New York, through New Jersey, and into eastern Pennsylvania. Today gypsy moths are found all the way from Nova Scotia to North Carolina, and west to Michigan and Illinois. Occasional specimens have been collected as far south as Florida and as far west as Missouri. One hundred years after its introduction, the species is still alive and well and continuing its move across North America.

The male moths are dark brown with small bodies and strong wings. The females are light tan with darker, irregular markings across the wings. The males have a wingspan of a little more than 1 inch (3 to 4 cm), compared with the larger females whose wingspan is slightly more than 2 inches (5.5 to 6.5 cm).

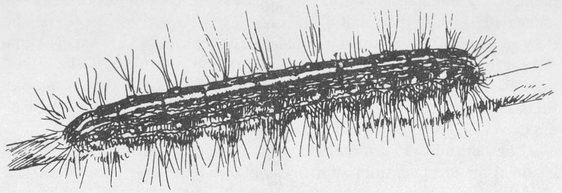

The eggs are laid during the late summer in masses from 1 to 1½ inches (2.5 to 3.8 cm) in length. Each egg mass contains anywhere from only fifteen to hundreds of eggs. The masses are covered with protective, buffy, hairy scales that originate on the female’s abdomen. They are usually laid on tree bark or stones, but can be found on any type of debris. They hatch in late April and May when the warm weather arrives. The larvae then climb up a tree, leaving a trail of silken thread. Once they reach the end of a twig, they walk off the tip and get picked up by a breeze. The thread and the long hairs on the caterpillar act as a sail, and the larvae are blown to other trees, where they climb to the top and get blown off once again. This ballooning behavior has proved to be an effective dispersal mechanism. After several trips from tree to tree, the caterpillars settle down to eating. Although they will eat the leaves from a wide range of different trees and shrubs, they seem to prefer oaks, willows, poplars, and birches. During years when there are major outbreaks of gypsy moth caterpillars and most of the preferred foliage is consumed, they will eat less favored species, such as pines, spruce, hemlock, and beech.

The older, hairy, brownish caterpillars are easily identified by the red and blue dots that appear in pairs on their back. In late June, they begin to pupate, emerging one and a half to two weeks later as moths. During the mating season that follows, the females emit a highly volatile chemical that acts as a powerful sex attractant. Downwind males detect the pheromone with their sensitive antennae, fly upwind until they find the larger females that are unable to fly, and they mate. The adult moths don’t live long after completing their reproductive function.

Like many other insects, gypsy moths have population swings. Major increases in numbers are followed by years with considerably fewer moths. During the years with low densities, predators such as some wasps, birds, mice, and various parasites keep the gypsy moth populations in check. However, it takes time to develop the checks and balances that keep populations of most native species stable. To date, though the population swings aren’t nearly as frequent as they once were, gypsy moths continue to have periodic outbreaks when their predators and parasites are unable to keep them under control; they end up eating virtually everything in sight.

After several years of declining numbers, gypsy moths again appear to be on the upswing. In 1985 about two million acres nationwide were defoliated, and twice as many acres were estimated to have been defoliated during 1986, according to John Neisess of the Department of Agriculture. Many types of control have been attempted, but all have been unsuccessful. New techniques are now being used to combat gypsy moths. One involves releasing the egg masses from specially bred gypsy moths into infested areas. The eggs hatch and grow into normal caterpillars, which then pupate and metamorphose into sterile adults. Eggs are produced as a result of matings between these moths and wild moths, but the eggs do not hatch. These carefully bred eggs can be produced in labs over a long period of time and stockpiled in cold storage until needed. The eggs are easier to handle and ship than the pupae or adults used in other sterility programs. It is hoped that this induced inherited sterility technique will suppress and contain low-density, expanding populations and thus protect highly sensitive natural areas, watersheds, and other high-risk areas. This method has been field-tested in several states, and larger applications are expected in the future.

Over the years we have learned much from the many different attempts to control the gypsy moth. One lesson is that it may not be worth the time or the expense to try to eradicate something that you haven’t a prayer of controlling anyway. Another lesson is that it is dangerous to spray entire states with chemicals that cause lethal short-and long-term effects. Although the defoliation caused by gypsy moths during the bad years is startling, forests do survive and sprout new foliage. We hate to see trees being stripped of all their leaves, but the best approach may simply be to grit your teeth and bear it. Many of the weaker trees don’t survive the defoliation, but they probably would have died anyway, though not quite so soon.

It may come as some consolation to know that many predators, competitors, and parasites are steadily incorporating these animals into their diets. Eventually the gypsy moths will be kept in check naturally.

Sometimes tent caterpillars are mistaken for gypsy moth caterpillars. The two larvae look quite similar, except that tent caterpillars have a white stripe down their back in addition to hairy bodies with blue dots. There are six species of tent caterpillar moths in the United States.

The eastern tent caterpillar moth (Malacosoma americanurn) and the western tent caterpillar moth (Malacosoma pluviale) can both be identified by the white webs or tents that they spin from silk threads in the forks of trees and shrubs during the spring (see the illustration). These caterpillars are most abundant in apple and cherry trees, to which they can do considerable damage. Tent caterpillars, native to this country, are social in nature, returning to the tents at night for protection. It has been found that the western tent caterpillars have a division of labor. Some of their larvae are leaders, moving out onto branches to look for the best areas in which to feed; others will go only where silken trails have been laid down, following the paths to active feeding areas.

Tent caterpillars and “tent”

Tent caterpillar

Their tents have an added thermoregulatory function: they act like greenhouses, warming up when the sun comes out and retaining some of that heat when the surrounding air cools. As a result, on spring mornings and afternoons, when the air is too cool for other species, the tent caterpillars are warmed up and all set to eat. They may even shuttle between the feeding spot and their tents, in order to warm up. This increases the number of hours during which they can feed. The higher temperature inside the tents may also elevate their metabolic rates and their rate of digestion, making them more efficient feeding machines. This means that the caterpillars can emerge very early in the spring when the leaves are most tender and when few predators are present as they rapidly pass through their most vulnerable stages.

Those who have an isolated population of tent caterpillar moths may find them easier to eliminate than a colony of gypsy moths, because the tent caterpillars congregate at night in their tents, where they can be readily caught and then killed. For widespread infestations, however, it may be best to take the same resigned approach that I recommended for gypsy moths.

HOUSE FLY

The flies represent one of the largest groups of insects. All these members of the order Diptera have only one pair of wings; their hind wings have been reduced to little projections that are important in maintaining equilibrium during flight. Mayflies, caddisflies, dragonflies, and sawflies carry the name “fly,” but they represent other orders, and they all have two pairs of wings instead of one. Most flies are small—some are incredibly small—and their bodies are soft and pliable. Black flies, horseflies, stable flies, punkies, and mosquitoes suck blood, and some of them are also scavengers. Of those that do not suck blood, many scavenge exclusively; these include blow flies, fruit flies, and house flies.

The house fly (Musca domestica) is now found all over the world and is one of the most common of the readily distinguishable urban flies. This fly multiplies rapidly, and populations, once established, tend to remain high. In 1911, C. F. Hodge calculated what would happen if a single pair of house flies continually bred from April to August, and all the offspring lived and reproduced, their offspring lived and reproduced, and so on. The number of flies that would exist at the end of the summer would be 191,010,000,000,000,000,000. He further calculated that these flies would cover the earth to a depth of 47 feet (14.3 m).

Obviously nature doesn’t work that way because of factors like limited resource availability, competition, predation, starvation, disease, and the weather. But when a new species is introduced to a locality where it has no natural predators or parasites, without immediate checks and balances, the population can run rampant.

I saw this happen some years ago when I arrived on the small isolated island of Mokil in the South Pacific shortly after a typhoon had carried in a new species of fly. The entire life cycle from egg to adult was completed in a matter of weeks, and several batches of 100 to 500 eggs were laid in a female’s lifetime. The island had a large supply of rotting breadfruit on which the flies could oviposit, or lay their eggs, and in a very short time the entire island was crawling and buzzing with flies.

The locals adapted with nonchalance; they didn’t seem to mind having flies constantly crawling all over them. I wasn’t nearly as complacent, being conscious that these creatures were probably carrying the pathogens of diseases to which I had built up little or no resistance. I had nicks and cuts all over my body from being knocked against a reef by the surf and from falling out of the trees I was climbing in search of eggs for use in taxonomic reseach at Yale University. Though the flies didn’t bite, they were fond of crawling all over my open sores, which never seemed to heal. Since these flies did not discriminate about crawling over me, over dead fish, or over excrement, it wasn’t long before my sores were harboring any number of staph infections.

I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the flies on Mokil, which is in the Eastern Caroline Islands in the Federated States of Micronesia, have long since come under check and are being controlled by predators and parasites. But considering how small that island is, it is difficult to say how long it could take for natural checks and balances to control this recently introduced fly.

The common house fly peaks in numbers during July and August. Another species, the lesser house fly (Fannia canicularis), which is slightly smaller and looks very similar, appears during May and June. Its larvae, known as maggots, differ from those of the common house fly in that they are flattened and have rows of spines. The flight pattern of the adult lesser house fly differs from that of the common house fly. Instead of buzzing around a room and landing on food, the lesser house flies are most often seen in the center of the room flying straight paths under a light fixture or dangling mobile. The flight is broken with erratic zigzags. Often several flies will fly together around the middle of the room. Most of these flies are males, and it is thought that the circling clusters are engaged in a behavior related to mating. Occasionally a male bolts off after a female that has been attracted to the cluster.

Another common fly is the face fly (Musca autumnalis), a new arrival to the United States. This fly is also similar to the common house fly, but it is slightly larger. It lives outdoors during most of the summer, coming inside when colder weather hits. Face flies will crawl into cracks and other small hiding places where they will overwinter, emerging on warm winter days or when spring arrives.

Other flies commonly seen in urban areas include bluebottle or greenbottle flies, which are blow flies, in the family Calliphoridae. They are distinguished by their shiny green or blue bodies, large size, and loud buzzing. It was a species of bottle fly that was blown into Mokil.

It has been shown that the common house fly is an important carrier and transmitter of over 100 disease-causing pathogens or the eggs of organisms that cause disease. These include amoebic dysentery, anthrax, cholera, gangrene, gonorrhea, salmonellosis, staphylococcus, and typhoid fever. Flies also carry the eggs of hookworm, pinworm, tapeworm, and whipworm.

Horse and human excrement are two of the preferred materials on which common house flies and lesser house flies breed. Since we now have flush toilets, and since horses are no longer common in urban areas, there are fewer flies in American cities than there were years ago. However, the eggs of house flies will hatch and the larvae will develop in many other types of organic matter, such as dead grass, rotting vegetables, and garbage. The recent advent of heavy plastic garbage bags has probably helped reduce urban fly populations. Of course, house flies are here to stay, but proper refuse disposal can substantially decrease the number of flies we have to contend with.

Horseflies, which are members of the family Tabanidae, are serious pests of humans and other animals because the females are bloodsuckers. Since horses were replaced by cars, most of the urban horseflies that inflicted painful bites have disappeared. And nobody misses them. But in affluent suburban communities where horses are kept, as well as in those cities where the police use horses and where there is a carriage industry for the tourists, as in New York, horseflies still persist, though in substantially reduced numbers.

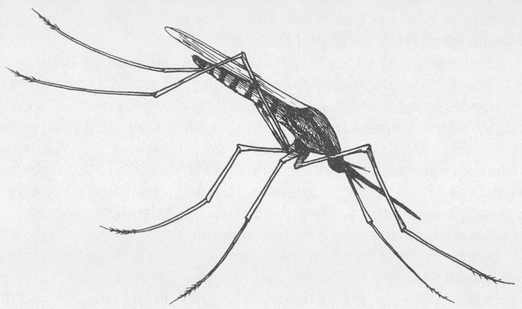

MOSQUITO

Another family of flies is the Cuculicidae, more commonly known as the mosquitoes. There are about 3,000 species of these small, widely distributed insects that are so well known they need little introduction. The adults can be distinguished from other similar dipteran families by such characteristics as the scales along the wing veins, by the specific arrangement of these veins, and by the long proboscis.

Mosquitoes lay their eggs either on the water’s surface or near the water, depending on the genus. The larvae, which are aquatic, swim by wriggling through the water, where they feed on different types of food, depending on the species. Most feed on algae and organic debris that are in suspension, floating on the surface, or lying at the bottom. Some larvae eat other mosquito larvae. Most species breathe air through a tube at the posterior end of the body, which they project through the water’s surface.