5

FISH

Many people fish for recreation at one time or another. Some go to a remote lake in the country and others go deep-sea fishing, but there’s a good deal of excellent fishing going on in most urban areas, too. It is not always wise to eat the fish, but they’re still fun to catch.

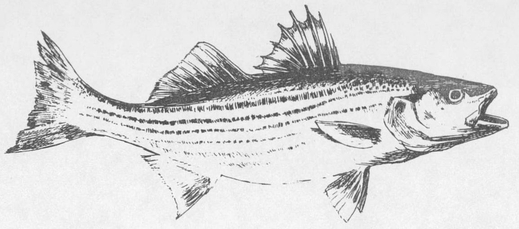

Some species of fish thrive in city ponds. Among them are pumpkinseeds, bluegills, bullheads, carp, goldfish, and largemouth bass. Other species feed, spawn, or migrate through the brackish or salty waters that surround coastal cities. Still other fish can be found in urban rivers. For example, the striped bass (Morone saxatilis), which has been declining in numbers along the East Coast, is known to frequent the old pilings on the Manhattan side of the Hudson River. Or when specific species are running, you will see city people fishing off bridges, from docks, or in the surf.

In this chapter I shall describe the more common fresh water species, and explain why they do well in urban environments while other species can’t compete. Some management problems are presented, along with solutions that have been tried with varying degrees of success.

COMMON CARP, GRASS CARP, AND GOLDFISH

City ponds are usually murky, turbid affairs, but they offer aesthetic appeal to city dwellers. They also provide valuable habitats to the species able to survive such conditions. We repeatedly find the same species turning up in these urban ponds.

Striped bass

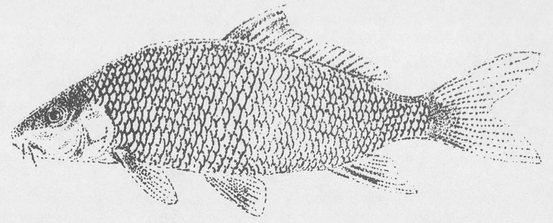

One of the most widespread city fish is the common carp, also known as the German carp (Cyprinus carpio). This good-sized fish reaches lengths of 1 to 2 feet (30 to 61 cm). It has large, conspicuous scales, and two pairs of barbels—beardlike projections that hang from the sides of the mouth. The carp is brownish on the back and sides, grading to yellow on the lower sides and belly; the fins usually have a reddish tint.

The carp and minnow species represent a very large family of fishes that inhabit fresh waters of Europe and North America. The family Cyprinidae contains about 200 genera and more than 1,000 species, of which about 225 are found in North America. This family has more species of freshwater fishes than any other.

Some people regard the common carp as the fishy equivalent of a weed. Since most disturbed freshwater habitats have sizable carp populations, it has become one of the more abundant species in urban lakes, ponds, and rivers across the United States. The carp’s tolerance of conditions that often accompany dense human populations has helped make it an urban success story, for fish. The fact that most other species cannot survive in urban waters partially explains why the carp has done so well.

The original range of the common carp encompassed the basins of the Black, Caspian, and Aral seas and may have included western Europe, the Volga River, the rivers flowing into the Pacific, and eastern Asia from the Amur River south to Burma. Carp were domesticated long ago in China, probably sometime between 800 and 300 B.C. They were an excellent choice for pond culture because they survived well under conditions that killed most other species, and they stayed alive when transported to market in tanks. Even now many fish markets carry live carp in cramped tanks, where they are ready to be pulled out and prepared fresh to a customer’s order.

Common carp

Around the first century A.D., the Romans independently discovered the merits of carp culture, obtaining their stock from the westernmost border of the species’ range, probably from the Danube River. Carp culture was primarily confined to monastery ponds at first; the escaped specimens helped increase their range during the Middle Ages. By the 16th century, carp were present almost everywhere on the European continent and were almost a staple in the diet of many Europeans. So it is not surprising to learn that they were brought to the United States and cultured in New York by the 1830s, when some were introduced into the Hudson River. In 1872, Julius Poppe, an early aquacultural entrepreneur, brought five carp from Reinfeldt, Germany, to the Sonoma Valley in northern California. From these original fish he bred enough to distribute their offspring through the western states, Hawaii, and Central America.

In 1876, a Professor S.F. Baird, U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries, hired a German fish culturist, Dr. Rudolph Hessel, to bring the best European fish to America. After several unsuccessful attempts, Dr. Hessel in 1877 introduced 345 young carp to ponds in Baltimore, Maryland. A year later, over 100 were removed and put into the ponds built at the base of the Washington Monument. In 1879, congressmen began sending carp home to their respective states. Demand for the fish peaked in 1883 when 260,000 carp were sent to 298 out of 301 congressional districts. The carp program ended in 1897. By then carp were so numerous that additional introductions were unnecessary, although they continued.

Since large females can lay up to two million eggs per season, the numbers of carp increased dramatically. In addition, carp often travel long distances and can survive an incredibly wide range of different conditions, including warm, shallow, muddy waters, clear mountain lakes, small streams, rivers, ponds, reservoirs, and even brackish estuaries. It has been estimated that carp may now be the most abundant fish species inhabiting the inland waters of North America.

As their numbers increased, the American public’s respect for the species decreased. Things got so bad that in 1962, when state and federal biologists attempted to rid a 450-mile stretch of the Colorado and Green rivers in Utah and Wyoming of all nongame fish, carp were one of the primary fishes targeted. The waters were treated with the piscicide rotenone (a chemical that kills fish), and the rivers were restocked with the desired game fish. Despite such drastic—and environmentally unsound—measures, most of the nongame fish populations recovered. Three species that were targets of the poisoning are now on the federal list of endangered species and are currently being raised in a fish hatchery where there is hope of ultimately restocking the rivers with them. They are the bonytail (Gila robusta jordani), the Colorado squawfish (Ptychocheilus lucius), and the razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus). Meanwhile, the carp is as common as ever. In fact, the use of the piscicide seems to have given them an edge over other fish in becoming reestablished.

For hundreds of years the Japanese have been breeding the common carp, selecting for a wide range of exotic colors and patterns, which now include beautiful hues of red, orange, yellow, blue, white, and black. Many of these fish are very costly, sometimes bringing as much as $1,000. The popularity of these fish has extended beyond Japan, and the exports currently amount to over $100 million per year. These Koi carp, as they are called, are put into ponds, indoors or outdoors, and are usually given excellent care, including the best water filtration, purification, and special foods, including brine shrimp, daphnia, worms, and trout pellets. Some of these fish have escaped and are mixing with wild populations. Soon, it may not be unusual for the occasional angler to pull in a strikingly colored carp.

Another cyprinid has been recently introduced. This one is the grass carp, also known as the white amur (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Since it is primarily herbivorous, it was brought here in order to evaluate its potential as a biological control agent for rampant aquatic plants. These fish were credited with much success in Russia, where 246,000 grass carp were introduced into the Kara-Kum Canal. The waterway had become choked with freshwater plants that impeded the flow of water needed to irrigate the cotton fields. The grass carp efficiently cleared the canal, and test trials have begun in other countries.

The introduction of this fish to North America presents certain ecological dangers, however. Grass carp are large, fecund, and adaptable, much like common carp, and they possess the potential to destroy aquatic plant beds that now provide cover for native species. Since grass carp are already widespread in the Mississippi River and many of its tributaries and have been collected in 35 states, it is only a matter of time until we know more about their effects on native communities. At this time we still don’t know whether they are breeding in the wild.

Recently I was asked to evaluate this species as a possible solution to the aquatic weed problems that New York City has in many of its park ponds. I recommended alternative solutions, such as erosion control to prevent runoff. It is runoff that fertilizes the water and causes the rich aquatic environments that feed large blooms of aquatic vegetation.

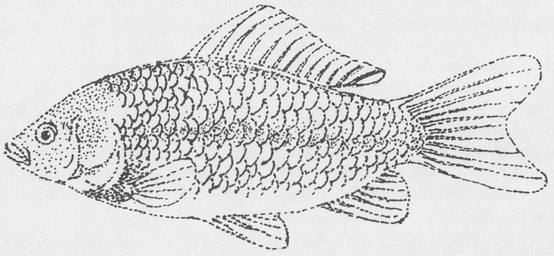

The goldfish (Carassius auratus) is a cyprinid that is native to the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, southern Manchuria, and Korea. It was known to range from the Lean River of eastern Europe to the Amur Basin and the Tym and Poronai rivers of Sakhalin. This was probably the first exotic fish species to be introduced into North America, brought here in the late 17th century. It has been collected in all of the 48 contiguous states, though there do not appear to be self-sustaining populations in Maine, Vermont, Florida, West Virginia, or Utah. This is one of the species found in most city ponds, released there by aquarists, ornamental pond fish hobbyists, and fishermen discarding excess live bait. Some goldfish may also have escaped from state and federal hatcheries where they are used to feed different species of game fish. Goldfish reach a length of about 1 foot (30 cm) and are as adept as the common carp at surviving in shallow, murky water, where both the goldfish and the carp will hybridize. Goldfish retain their bright orange color after being released into the wild, though they tend to revert to their natural brown or olive coloration after several generations.

Goldfish

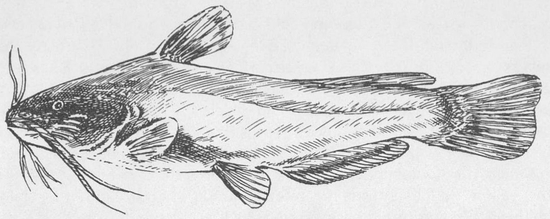

Bullhead

BULLHEAD AND CATFISH

The North American freshwater catfish are members of the family Ictaluridae. They are known as catfish because of their whiskers, or barbels, which are thin soft appendages extending from their lips (two nasal, two maxillary, four chin). Their skin is naked—that is, they have no scales—and all the species occurring in the United States and Canada have a spine on the leading edge of their dorsal (back) and pectoral (side) fins. There are several genera in the family. The members of one group of species in the genus Ictalurus are generally known as bullheads, but they are also called catfish and horned pout in different regions of the country.

Bullheads are rather stout in body shape, with a head that is large and wide. There are several species in the United States. Bullheads were once found in virtually every pond and slow stream in the eastern half of the country. Now, due to introductions, they are also abundant on the Pacific Coast. These species vary in appearance and are not easily differentiated. Distinguishing characteristics include the number and length of anal rays, whether or not the lower jaw protrudes, and the length of the pectoral spine. Bullhead species were hard to tell apart to begin with, but now that these fish have been introduced all over the country, the entire group is a mess. To add to the confusion, much of the older literature calls the bullheads Ameiurus, but that genus has recently been subsumed by the genus Ictalurus.

The common bullhead, or brown bullhead (Ictalurus nebulosus) ranges from Maine westward through the Great Lakes to North Dakota and south to Florida and Texas. It is also abundant in the West where it has been introduced and is now well established. Because this species naturally thrives in slow rivers and weedy ponds and lakes, they do well in city ponds, which are often murky and overgrown with algae and other aquatic plant life. Common bullheads will reach about a foot (30 cm) in length, though larger ones have been recorded. They are among the several species of fish that state fisheries usually dump into lakes and ponds when they stock an area. This accounts for the bullheads having been introduced everywhere. Sometimes a closely related species may be used in place of a fishery species that is in short supply. The result has been that yellow bullheads (Ictalurus natalis) and black bullheads (Ictalurus melas) are found in many places alongside the brown bullhead. While the yellow bullheads usually prefer clear, flowing streams, the black bullhead tolerates turbid backwaters as well as city ponds from New York to Tennessee, west to North Dakota, and south to Colorado.

Bullheads breed during mid- to late spring and early summer when the water temperature reaches about 70°F (21°C). The male selects and clears a shallow depression, usually sheltered by rocks, logs, or vegetation. The female then drops her eggs, which stick together in firm, cream-colored, jellylike clusters. The eggs, which are about  inch (3 mm) in diameter, are fertilized as they are laid. Afterward the male stays with the eggs to keep away predators and to fluff or fan the eggs, which he does with his pelvic fins. Sometimes the males are observed sucking the eggs in and out of their mouths. All this motion keeps the water in constant circulation over the eggs, which is important for their development.

inch (3 mm) in diameter, are fertilized as they are laid. Afterward the male stays with the eggs to keep away predators and to fluff or fan the eggs, which he does with his pelvic fins. Sometimes the males are observed sucking the eggs in and out of their mouths. All this motion keeps the water in constant circulation over the eggs, which is important for their development.

The eggs hatch in about five days when the water is around 77°F (30.5°C). The jet black young are about ½ inch (13 mm) long when they hatch, and are attended by the adults until they reach twice that size. The young school together during the first summer, usually hidden in vegetation or under objects near shore. One reason they are sometimes found under floating boards or boats may be because the young and adults are largely nocturnal; they seek dark areas during the day. As it gets darker each evening, their activity increases. Fishermen report catching the adults at night, often in deep water, where the bullheads tend to spend much of their time right next to the bottom. Being bottom feeders, they eat a range of material including plants, worms, insects, mollusks, and occasionally even other fish.

The barbels appear to be useful when the fish feed in dark, murky waters. They are often thought of as feelers, but that does not appear to be their only purpose. It has been shown that each bullhead has tens of thousands of taste buds all over its body, and the tips of the barbels contain the greatest concentration of taste buds. Fish, like other vertebrates, smell and taste through two separate channels. Each channel responds to a different kind of stimulus, though there does tend to be some overlap. The fish’s taste capabilities, like ours, are restricted to sweet, salty, sour, and bitter compounds.

The chemicals that fish smell belong to a variety of substances that are very volatile. It has been found that bullheads are able to recognize one another as individuals, and it is primarily the nose, and therefore the sense of smell, that mediates such recognition. Experiments have shown that bullheads smell the dilute concentrations of slime produced by the mucous glands in their skin. When this mucus is dissolved in the water to even very weak concentrations, it is still recognizable by other bullheads. It is interesting that each fish has its own chemical signature that is probably the result of a combination of several different chemicals. With such keen senses, bullheads are able to identify and locate food without having to see it. The more visually oriented species, such as bass, pickerel, and trout, do not have this ability.

The spines in the dorsal and pectoral fins appear to be formidable weapons when bullheads are dealing with predators. Any animal attempting to swallow a whole bullhead finds the painful spines sticking in its throat or gut a powerful incentive to disgorge the fish and avoid making a similar mistake in the future. Some catfish species have poison glands in their spines, but in the common bullhead such glands are either not present or are rudimentary.

Bullheads are able to survive for hours out of water without lasting detrimental effects. They have accessory breathing structures that allow them to use their air bladders as something akin to a lung, thereby breathing atmospheric air rather than just air that is dissolved in water. A few other American fish have such a capacity. They are the bowfin (Amia calva), the common carp (Cyprinus carpio), the common eel (Anguilla rostrata), and the tench (Tinca tinca). These breathing structures may be part of the reason bullheads and carp are able to survive the deoxygenated condition of many city ponds, particularly during late summer when bacteria, digesting the rotting plants and algae, consume much of the available dissolved oxygen. Conditions become very stressful then for many aquatic animals, including fish and tadpoles. This is when you see these species coming to the surface to take gulps of air. There are even reports that bullheads are able to survive for several weeks encased in mud when ponds dry up.

Some catfish, especially the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) are kept in ponds where they are fed and grown as a valuable crop. Yields on such a project can be as high as 2,000 pounds per acre. The brown bullhead is also used in aquaculture. In 1984, some 470 million pounds of cultured fish and shellfish were raised in the United States—12 percent of the total fish and shellfish produced in this country. Of the catfish commercially sold annually, 95 percent are grown on fish farms.

Several years ago newspapers were full of reports about walking catfish (Clarias batrachus), which had been introduced to Florida and were taking to land, moving from one body of water to the next. This species, a member of the family of air-breathing catfish, Clariidae, is found in fresh and brackish waters in Sri Lanka, eastern India, Bangladesh, Burma, the Malay Archipelago, Syria, and much of Africa. Albino juveniles of this species were first imported to Florida during the early 1960s from Bangkok, Thailand, and were sold in pet shops. Later, adults were brought over for breeding. Some of these walking catfish escaped or were released from culture facilities. As of 1968 they were found in only three Florida counties, but by 1978 they had spread to twenty counties in the southern half of peninsular Florida, and their range is still expanding, though at present the cooler regions to the north are thought to be confining their population growth.

Aquarists may be interested to know that at least three species of suckermouth catfish, all in the genus Hypostoma, family Loricariidae, are now established in this country as well. The genus is native to South America, from the Rio de la Plata system north to Panama and Costa Rica. One population has been reported in Six Mile Creek near Eureka Springs, Florida. Another species is established in Indian Spring, Nevada, and the third population is in the San Antonio River in Bexar County, Texas. The Florida population is probably the result of released aquarium fish; in Texas the population stems from the San Antonio Zoological Gardens.

PERCH

Another family, the Percidae, or perch, has members distributed through much of the northern hemisphere. These fish naturally occur in North America east of the Rocky Mountains, extend well into northern Canada, and have been introduced to the Pacific slope. Members are also found in England and most of Europe, and as far as western and northern Asia. The family contains 9 genera and 146 described species, though there are several others that have yet to be described. Most species are quite small, but some members of the family, such as the walleye (Stizostedion vitreum), will grow as long as 3 feet (91 cm).

The family, though diverse, is identified by two dorsal (back) fins, which are either separate or narrowly joined, one or two anal spines, five to eight branchiostegal rays (the long curved skull bones just below the operculum that support the gill membranes), and thirty-two to fifty vertebrae, as well as other characteristics. Only the yellow perch (Perca flavescens) commonly occurs in urban and suburban ponds and lakes in the United States; most of the other species are less well known or rarely live in heavily populated regions.

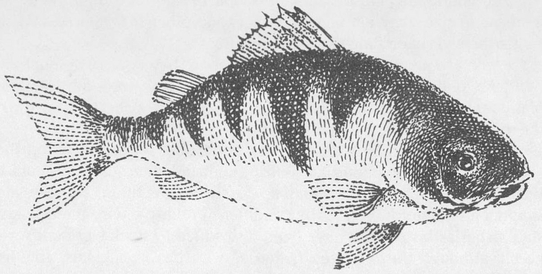

Perch

For comparative purposes, it’s helpful to know that perch have two dorsal fins, whereas sunfish have just one. The dorsal fins of pike, salmon, and trout are short and lack the support of stiff, bony spines. While the anal fin—the fin on the underside of the body, toward the tail—of the perch contains one or two thin, weak spines, that of the sunfish has three or more obvious spines toward the front. The pike, salmon, and trout never have any spines in front of this fin. Also, no member of the perch family ever has a dark spot on the gill like the ear spots or ear flaps found among the sunfish. Some of the perch are nearly as flat and platelike as are many of the sunfish.

The yellow perch rarely gets more than 6 to 10 inches (15 to 25 cm) long. Its weight ranges from ¼ to ¾ pounds (114 to 341 gm), though larger specimens are caught from time to time. It has an olive back, yellowish sides with six or eight distinct, dark vertical bars interrupting the lighter colors. The lower fins are usually reddish orange, especially in the spring. Spawning takes place when the water reaches 45 to 50°F (7.2 to 10°C).

As many as a dozen males will follow the female, fertilizing the strings of eggs as they are laid. Each string of eggs may be several feet long and can contain 10,000 to 50,000 eggs. The eggs are laid in shallow water, either on submerged stones, branches, and roots, or on the dense growths of aquatic vegetation that often occur in city ponds. In these environments yellow perch often lay their eggs on plants such as elodea (Anacharis spp.), water milfoil (Myriophyllum spp.), water buttercup (Ranunculus spp.), water marigold (Bidens spp.), coontail (Ceratophyllum spp.), water nymph (Najas spp.), and fanwort (Cabomba carolinia). The adults do not guard the eggs, which will hatch in about three weeks.

The young feed mostly on microscopic organisms at first. As the fry increase in size, they eat aquatic insects and other invertebrates. When larger they will eat minnows and other fish.

Perch are popular among anglers, though they don’t give much of a fight. Anyone can catch them anytime, since they strike all year long. Many feel that, among freshwater fish, this has the sweetest flesh and is the most delicious.

Perch can often be found in park ponds, but for some reason they are not nearly as common as sunfish, bullheads, and carp. It could be that yellow perch cannot stand up to the competition, or they may simply be unable to tolerate the conditions in these environments. Also, state fisheries historically have been disinclined to stock city ponds with perch, although they’ve been generous with bass, bullheads, and sunfish. Where perch have been introduced, they tend to reproduce in such numbers that they overpopulate the ponds, and their size becomes stunted. It would seem that they are not sufficiently cannibalistic to control their own numbers when stocked alone, and if they occur with other fish that aren’t piscivorous, the competition may not be enough to control their numbers.

SUNFISH AND BASS

Sunfish are members of the largest vertebrate order of all, the Perciformes. This is the most diverse of the fish orders. It is the dominant group of oceangoing vertebrates as well as the dominant fish group in many tropical and subtropical fresh waters. The family Centrarchidae, or sunfish, is a freshwater group found in most of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. One species, the Sacramento perch (Archoplites interruptus), is native west of the Rocky Mountains.

Several characteristics identify the members of this family. These fish are unique in that they have three or more anal spines, a small, concealed pseudobranch, or false gill, and five to seven branchiostegal rays (the bones that support the gill membranes), as well as separate gill membranes. Most sunfish are nest builders, and they range in size from less than 2 inches (4 cm) to almost 3 feet (91 cm), the record for the largest largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides).

Sunnies, bluegills, pumpkinseeds, sunfish, and crappies are all members of this group, which includes nine genera and thirty species. Other members of the family include largemouth and smallmouth bass and rock bass. One or more of these species live in almost every part of every state east of the Rockies.

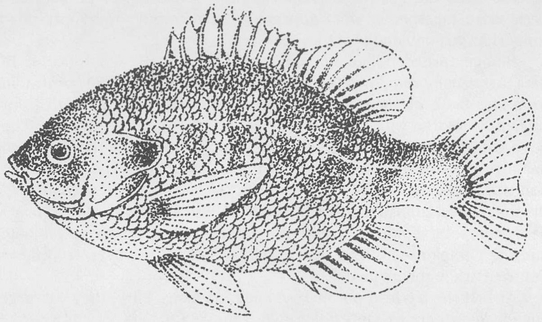

Bluegill

Sunfish are known to nearly everyone. They are the bold little fish that you see near the shores of streams, ponds, and lakes, in clear water as well as in most of the murkier city ponds. They are a beginner’s fish; children fishing at the water’s edge usually catch sunfish before catching anything else. And since sunfish are drawn to a wide variety of live bait and artificial lures they are also a good sports fish.

Sunfish are diurnal; that is, they are active during the day. They feed on insects, small crustaceans, snails, and sometimes on smaller fish. They find food primarily by sight. Their jawbones and muscles are extremely versatile, enabling them to inhale their food whole. Upon approaching prey, a sunfish thrusts its jaws forward and out, increasing the amount of space inside its mouth, which is then filled by water and whatever prey may be at hand. The size of a fish’s mouth and stomach will limit the size of the prey it can take. Some of the largemouth bass and the green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus) can take prey up to half their size.

In early spring, most members of this family leave the deeper, cooler water where they overwinter and move into shallow, warmer waters along the shore. The males select and clear the nest sites, using their fins to fan away the silt until the gravel, sand, or clay bottom is exposed. They usually make their nests out in the open without any overhanging logs or rocks and without any nearby aquatic vegetation. You can easily observe these cleared areas from shore. They look like circular, light-colored patches, usually with a male standing guard nearby. Bluegills (Lepomis macrochirus) and pumpkinseeds (Lepomis gibbosus) often prepare their nests close together in what appears to be a colony. Many city ponds support large populations of these species.

Bluegills are identified by their light blue to slightly reddish color, the bars that usually run down their sides, and the dark “ear spot” protruding from the back of their gills. Pumpkinseeds, or common sunfish, are brilliantly colored with tinges of yellow, orange, and brownish red. They have a distinctive dark ear spot or ear flap; in the adults, this protrusion has a bright orange, red, or scarlet tip. Other species recorded in city ponds include the black-banded sunfish (Mesogonistius chaetodon) and the long-eared sunfish (Lepomis auritus). These species do not appear to be as competitive and well suited to city park ponds as are the bluegill and the pumpkinseed. As a result, neither species has been recorded in Central Park in recent years.

At first the fry feed on microscopic organisms; later, they eat larger aquatic invertebrates. Only full-grown crappies and bass are known to eat other fish. The growth rates largely depend on food availability. In city ponds, which are often crowded, a large number of sunfish will be abnormally small. Part of this stunting may be a result of the species composition. In healthier, cleaner ponds and lakes, where a wide range of species exists, the larger, more predaceous species feed on the smaller fish. But in city ponds the number of species is often quite limited. As a result, the large numbers of each species may have the effect of reducing the overall size of the individuals. Also, since smaller individuals can survive and breed, the gene pool may actually shift to favor the smaller fish.

In North America, bass are among the best freshwater game fish. Only warm water species—those that do well in water that remains above 74°F (23°C) all summer—will be found in urban ponds and lakes. Smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieui) and spotted bass (Micropterus punctulatus ), which naturally inhabit clear streams, have been introduced to some lakes and reservoirs, where they do pretty well. But only the largemouth bass has taken well to the shallower, warmer, and murkier urban and suburban lakes, ponds, and impoundments. However, like the other species in this family, bass locate their food visually, so the water cannot be too turbid. Largemouth bass are identified by a longitudinal stripe down each side, a greenish back, and a whitish belly. Unlike the smaller sunfish, some bass reach 5 to 10 pounds (2.3 to 4.5 kg), and occasionally even larger. The record bass, caught in Florida during the 1930s, weighed 22 pounds (10 kg).

In ponds that are overpopulated with stunted sunfish, the tiger muskellunge has been introduced. This fish, a cross between the northern pike (Esox lucius) and the muskellunge (Esox masquinongy), is sterile. When tiger muskellunges are stocked in a pond, they will thin out the stunted fish, providing a better fishery. The surviving sunfish grow larger, and the largemouth bass no longer have to contend with sunfish constantly raiding their nests. Since the tiger muskie does not breed, it never has a detrimental effect on the numbers of bass. Both the northern pike and the muskellunge are members of the pike family, Esocidae. These fish can be recognized by the duck-bill shape of the front of the head. Because they require clear, cool, weedy waters that don’t fluctuate much in level, they have difficulty breeding in the warmer ponds typically found in urban and suburban areas.