7

REPTILES

The fact that any reptiles at all can live in cities is remarkable. Like birds, most reptiles lay large, conspicuous, shelled eggs. That works out all right for many urban bird species because most are able to nest up off the ground, where their eggs are far less vunerable to predation. But a city is a terrible place to live if, like the reptiles, you have to lay your eggs on the ground. Certain birds have been able to do this with some success—the pheasant may be the best example—but most ground-nesting urban birds now lay their eggs on flat roofs. Unfortunately, reptiles have to bury their eggs, so they don’t have the luxury of laying them on roofs, and most reptiles couldn’t climb a building anyway. As a result, we have a relatively depauperate urban reptile fauna.

Reptiles found in cities fall into several categories. One is composed of pet turtles that have been released in ponds and lakes. Though these turtles may do well, most species cannot reproduce themselves. Some have been released in the wrong part of the country, others can’t find a mate, and still others can’t find a suitable place to lay their eggs. The eggs or the young might not survive very long anyway, given the many rodents and other obstacles they have to overcome. Yet, as it turns out, turtles actually do survive and even reproduce in many city ponds, and they are discussed in this chapter.

The second group of urban reptiles is the lizards. Because most lizards live in warm climates, we don’t find many species in the urban areas of the north, but the exceptions are discussed. Urban lizards are found in the most southern portions of this country. There are many lizards living in the Miami area, and information about each of them is offered, along with facts about lizards in other cities around the country.

Snakes make up the third group of urban reptiles. Snakes aren’t the most beloved of animals, of course, so it stands to reason that there aren’t many of them in most cities. Even those snakes that have been able to survive in cities and suburbs are not doing well, for the most part. Generally, these populations are relictual and probably won’t survive much longer. But there are some exceptions, and these species are discussed.

SEA TURTLES

Seven species of sea turtles live in the coastal waters of the United States. Four of them—the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), the loggerhead (Caretta caretta), the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), and the hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata)—live in both the Atlantic and the Pacific. Recently the Pacific subspecies of green turtle (Chelonia mydas agassazi) was elevated to its own specific status, Chelonia depressa, the flatback turtle. The names of the other two species—the Atlantic ridley (Lepidochelys kempi) and the Pacific ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea)—will tell you where they live.

Usually sea turtles are thought to inhabit remote, tropical regions, far from human disturbance. In part, this perception is true, but largely it is a reflection of how poorly we understand these animals, all of which are endangered. Over 99 percent of sea turtle research focuses on nesting behavior, egg incubation, and hatchling emergence, even though this represents less than 1 percent of their life history. We know little else because it is difficult to study these turtles during their extended migrations, often more than 1,250 miles (2,000 km), to remote feeding areas and nesting beaches. The only time most researchers find it feasible to study them is when the turtles congregate at their nesting beaches. As a result, we are left with a very lopsided understanding of sea turtle biology. This may explain why it comes as such a surprise to learn that although sea turtles tend to return to the same tropical beaches to lay their eggs, they travel far and wide at other times, sometimes feeding in the waters near major coastal cities.

For years the Atlantic leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea coriacea) was thought to be rare off the East Coast. However, an artifact of our times has revealed the presence of more leatherbacks than we suspected. Dead leatherbacks weighing from 700 to 1,000 pounds (318 to 455 kg) now regularly wash ashore along the New York and New Jersey coastlines. A leading cause of these deaths seems to be an important component of their diet: they eat jellyfish—or what they think are jellyfish. The garbage being flushed and dumped into our coastal waters includes many plastic bags. In the water these bags look much like jellyfish, and they are being consumed by unsuspecting leatherbacks. The plastic then clogs the turtles’ alimentary canal and eventually kills them. Boat propeller damage also takes a large toll. It is difficult to tell if the turtles get hit by boat propellers because they are not wary of fishermen, or if the turtles, already dying, are spotted, then run over by curious boaters.

The leatherback turtle is easily distinguished from all other sea turtles by the twelve ridges on its leathery shell, five above, five below, and one on each side. The older leatherbacks can grow up to 8 feet (2.5 m) long, and can weigh as much as 1,600 pounds (726 kg).

Recently loggerhead sea turtles have been turning up in unlikely places, leading some people to believe that they are regular visitors to urban marine waters. For years it has been occasionally reported in the Northeast that a loggerhead has been hooked by anglers from the shore. This sea turtle was known to be a regular summer visitor as far north as Cape Cod and Long Island, frequently entering inlets. I have substantial reason to believe that loggerheads have always frequented these coasts. Dead specimens have washed ashore in Queens and Brooklyn, and Don Riepe, who works at the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, reports having seen turtles fitting the description of loggerheads in Jamaica Bay, New York City. Despite the considerable pollution in these waters, horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) are still doing quite well; each year they come into shallow water to mate and lay their eggs. It could be that these breeding aggregations lure in the loggerheads, which are known to eat a wide range of foods, including such hard-shelled animals as horseshoe crabs. One of the dead loggerheads that washed ashore in New York City during the summer of 1979 was opened up by Matthew Lerman, a high school teacher in Rockaway Park, Queens. He found remains of horseshoe crabs in the digestive tract.

Loggerheads are identified by their five or more lateral laminae, the plates on each side of their carapace, which is the shell on their back. Also, they have two pairs of scutes, thin, horny, shields, in contact with each other on the top of their head between their eyes. The old ones can get as large as 7 feet (2.13 m) and weigh as much as 1,200 pounds (544 kg).

Another sea turtle, the Kemp’s ridley, also known as the Atlantic ridley, has three ridges running down the top of the shell, and five lateral laminae on each side of the carapace. They only grow 2½ feet (76 cm) long, weighing about 100 pounds (45 kg). This species has also been found to frequent the waters of some unlikely urban areas. It is the most endangered of all the sea turtles. Like the loggerhead, the ridley lives in shallow coastal waters where it feeds on crustaceans, gastropods, echinoderms, and some marine plants. Both species, along with some hawksbills, are being drowned in fishing nets and shrimp trawls in the waters off the southeast coast. The sea turtles get caught in the nets and, unable to surface for air, expire. It would help the turtles considerably if fishermen were forced to trawl farther offshore where they will catch fewer turtles and, in the process, preserve a greater portion of the shrimp spawning grounds. Nets have been redesigned to avoid drowning of turtles, but of the more than 6,000 vessels towing more than 20,000 shrimp nets in southeastern U.S. waters, no more than 300 vessels are using the new turtle-excluder device.

Sea turtles occasionally become stranded in urban or suburban waters. The New York Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Stranding Network, operated by the Okeanos Ocean Research Foundation, began recording data on sea turtle strandings in 1977. From 1977 to 1984 they averaged 24 turtles a year. The most numerous were leatherbacks; only a fraction were loggerheads, Kemp’s ridleys, and green turtles. Then in late 1985 and early 1986, 52 stranded sea turtles were recovered from the New York shores of Long Island Sound. Most of the turtles were found washed ashore or floating in the surf along the north shore of Long Island. Among the 52 turtles recovered were three different species: Kemp’s ridleys, green turtles, and loggerheads. It was thought that all were stunned by severely cold temperatures. Thirty-nine of the turtles were positively identified as ridleys, and two more were probably ridleys. All of them were nearly the same length, between 9 and 13 inches (23 to 33 cm) measured from notch to notch along the carapace. Ridleys this size are all immatures. These cold-stunned turtles have led researchers to question whether Long Island Sound has always been part of their normal, but previously unrecognized, habitat during this stage of their life. It has also been suggested that this was an anomalous event caused by a change in the Gulf Stream, the major northward flowing current in the western Atlantic, and that the turtles may have followed eddies of warm water that led into Long Island Sound. However, Sam Sadove, program coordinator for the Stranding Network and research director for the Okeanos Foundation, suggests that the waters of Long Island Sound may serve as an important habitat for developing juvenile Kemp’s ridleys.

Green turtles, though found in our coastal waters from Massachusetts to Mexico, and from southern California to Chile, are uncommon almost everywhere throughout their range except in the Caribbean and around the Galapagos Islands. The adults tend to be extremely rare in the more northern waters, but the juveniles appear to tolerate cooler temperatures, and they range farther north. This species, like the hawksbill, has four lateral laminae. Unlike the loggerhead and the hawksbill turtles, the green turtle does not have two pairs of scutes touching each other on the top of the head between the eyes.

Green turtles are uncommon in most of their range, and they are seldom seen near urban areas, but where conditions are right and where there are beds of turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum) to graze on, they will come in near shore, even near people and constant motorboat traffic, and feed at their leisure in large groups. I have seen this during summers in Bermuda, where hundreds of juvenile green turtles feed. They readily graze on stands of turtle grass in Castle Harbor, which is near the island’s busy airport, some of its largest hotels, and considerable boat traffic.

I know of no true urban areas where hawksbills are common. These turtles, which grow only about 3 feet (91 cm) long and 280 pounds (127 kg) in weight, range in the western Atlantic from Brazil to Massachusetts, and in the eastern Pacific from the California coast to Peru; they seem to be rare throughout. At one time they were relatively common in the waters along the southeastern United States, but now they are found only on occasion off North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. There may be more hawksbills farther off the coast than is currently recognized, because from time to time they are seen in the waters off most tropical islands. This turtle has the best shell for “tortoise shell,” causing severe pressure on them throughout their range. In the tropics, especially, the natives supply a bountiful trade, kept lively by droves of tourists. Even though real tortoise shell is an illegal import, as long as there’s a market, and insufficient numbers of people hired to enforce the laws, hawksbills will risk paying the supreme price, extinction.

PAINTED TURTLES

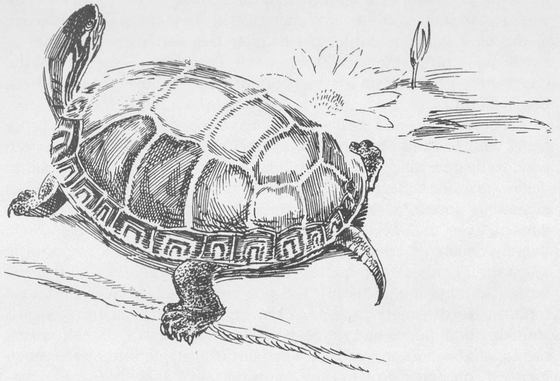

The painted turtle is probably one of the most numerous turtles in North America. This turtle thrives in conditions where few other animals survive. Four subspecies in the United States have an aggregate range extending over the East, Midwest, and Northwest. Painted turtles have stripes of uniform width along the neck, beginning red and becoming yellow farther out on the head. The length of the shell rarely exceeds 6 inches (15 cm). The background color of the carapace is quite dark, while the scutes along the margins are black, red, and yellow, and the scutes along the sides and back are bordered with yellow. The bottom shell, the plastron, is usually yellow.

The eastern painted turtle (Chrysemys picta picta) is distributed from Nova Scotia to Alabama, overlapping considerably from Maine to Pennsylvania with the midland painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata), which has some dark markings in the middle of the plastron. The midland subspecies appears to be better adapted to the cooler temperatures of the upland, while the eastern painted turtles, which are distinguished by their pure yellow plastrons, are better adapted to the warm coastal plain of the Atlantic Coast. Some populations of midland turtles colonized coastal land masses when the last glaciation ended and the glacier receded northward. As the glacier melted, the sea level rose, isolating many areas, which became islands. When the climate warmed, eastern painted turtles moved north and mixed with the midland stock, but they couldn’t mix with the stock that had become established on the coastal islands because painted turtles avoid salt water.

Painted turtle

The southern painted turtle (Chrysemys picta dorsalis) has the most restricted range of the four subspecies. It is found in a strip of territory extending from southern Illinois and Missouri south along the east and west banks of the Mississippi to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana. Their range also includes an eastward extension through northern Mississippi and Alabama. There is also a relictual population in southeastern Oklahoma. This subspecies is distinguished from the others by a prominent red or yellow stripe that runs right down the middle of its back.

The western painted turtle is the only painted turtle with a reticulate carapacial pattern, that is, a netlike design on its top shell that is not part of the sutures, or seams, between the scutes, or plates, that cover the shell. It ranges from western Ontario through southern Canada to British Columbia, south to Missouri, and west through most of Kansas, then diagonally northwest to northern Oregon. There are other isolated populations in Colorado, New Mexico, and Chihuahua, Mexico. In the Northwest, where reptiles are less common than in warmer regions, this is one of the most common turtle species after the western pond turtle, or Pacific pond turtle (Clemmys marmorata). The latter ranges west of the Cascade-Sierra crest from southwestern British Columbia to northwestern Baja California.

The western pond turtle doesn’t have the red and yellow stripes along the neck and head that the painted turtles have, and the western pond turtle’s carapace is a uniform, dark color without any bright red or yellow markings. Because the western pond turtle is aquatic, and is commonly found in ponds, marshes, streams, rivers, and irrigation ditches, even in brackish coastal waters, it is far more numerous in densely populated areas than are its eastern relatives, the wood turtle (Clemmys insculpta), the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata), and the bog turtle (Clemmys muhlenbergi). The bog turtle is often called the rarest turtle in North America. Each of the eastern species in this genus is shrinking in numbers and range, perhaps because much of their critical habitat has been destroyed. The wood turtle, characterized by the superimposed concentric growth rings on its dorsal laminae, has several specific habitat requirements; if one is not met, the turtles are unable to maintain their numbers in the area. The spotted turtle, which rarely exceeds 5 inches (12.7 cm) in length, is recognized by the bright yellow spots on the almost black shell. And the bog turtle, a small brown turtle with yellowish orange blotches on each side of the neck, cannot live long without adequate acreage of wetlands and with an adjacent upland area in which to lay its eggs.

The painted turtle and western pond turtle thrive because they do well in the ponds that are distributed in areas where people live. But without well-targeted conservation efforts, all three of the other species related to the western pond turtle could continue their decline until only a few, protected, isolated populations survive.

SNAPPING TURTLES

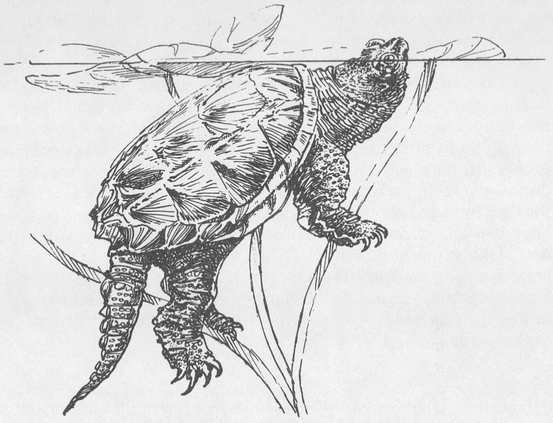

The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina serpentina) has a range that extends from southern Canada to northern Florida and west to the Rocky Mountains. Some people regard the Florida snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) as a subspecies of the snapping turtle. Others have elevated it to a species (Chelydra osceola). This turtle, at any rate, ranges from northern to southern Florida. These snapping turtles spend most of their time in aquatic habitats, including streams, marshes, and ponds. In many coastal areas they live in brackish habitats, and on occasion are found in pure saltwater. Their capacity to thrive in a variety of aquatic habitats may have some bearing on their ability to survive where most other amphibians and reptiles were extirpated long ago, including urban and suburban ponds. This is a turtle with endurance. Seldom seen by most people, the snapping turtle spends much of its adult life resting on or moving along muddy and weedy water bottoms, eating whatever animal matter is available.

Snapping turtle

For a freshwater turtle, this species is rather large. The shell (carapace) of older adults often reaches a length of a foot (30 cm) or more. The carapace is dark brown to black and becomes quite smooth with age. The head is large and pointed, and when the mouth is opened, the turtle looks fierce, which it is. The yellowish plastron is small and cruciform in shape, leaving much soft skin exposed. The skin along the neck has dark tubercles on it, and the especially long tail is equipped with a considerable amount of armor.

Many people are afraid of snapping turtles. They think the turtles pose a significant threat to bathers. Actually, these people have little to worry about. It is true that snappers can leave a nasty wound, but they bite only when they are out of the water being bothered. As far as I know, no one has ever claimed to have been bitten underwater. The turtles mind their own business and are very willing to leave people alone. People should take the hint.

Unlike most turtles that have a problem finding safe places to lay their eggs in urban settings, snapping turtles often locate suitable nesting sites quite close to the urban ponds in which they thrive. Since people are often afraid to enter city parks at night, the turtles have many hours to accomplish their egg-laying tasks after dark without being noticed or disturbed, except perhaps by raccoons and other animals. Urban turtles usually lay their eggs during overcast, cloudy, or rainy weather, or at dusk, dawn, or during the night. Nocturnal egg laying appears to be the norm with snapping turtles, which are sometimes caught in the act by joggers out for an early morning run around the city pond. Even in Manhattan, snappers have occasionally been found methodically completing their time-honored egg-laying ritual just before or just after the sun comes up.

MUSK TURTLES

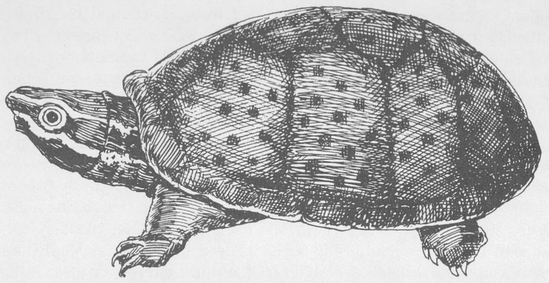

Four species of musk turtles in the genus Sternotherus can be found in the United States, some of them in city and suburban parks. The group gets its name from the foul-smelling secretion emitted by their musk glands. All are limited to the eastern part of the country. These are small, inconspicuous turtles with carapacial lengths ranging from about 3½ to 5½ inches (9 to 14 cm). The most common musk turtle, known as the stinkpot (Sternotherus odoratus), inhabits clear, shallow ponds and lakes as well as rivers in most eastern states. Indigenous to a large area, this species ranges from Maine’s coastal region to the southern tip of Florida, west to Wisconsin, and south to the Gulf Coast. The carapace may be light to dark brown, with or without spots, and is often covered with a green algal growth. The plastron is a light cream or yellow color, while the head and soft parts are all quite dark. Small, narrow, and roughly cruciform, the plastron is more like that of the snapping turtle than most of the other freshwater turtles. Unlike the snapping turtle, the shell is domed, the size is always small, and the tail is short.

The stinkpot has been eliminated from many of its former localities. During the decades when DDT and other pesticides and herbicides were being used widely, many detrimental effects were set in motion. It took years before people noticed that animals at the top of the food chain, such as ospreys (Pandion haliaetus), peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus), and bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), were decreasing in numbers. And it was even longer before the government finally got around to banning the use of the worst of these chemicals. In the meantime, the poisons accumulated in the groundwater and sediments, as well as in the tissues of organisms throughout the ecosystem, and their effects continued to ripple through the environment. Substantially less conspicuous animals, such as amphibians and reptiles, tended to be overlooked by the press and the government, not to mention the scientific community, but their numbers, too, decreased dramatically. Evidence that I have gathered from a region in Long Island, New York, indicates that many of the species of lower vertebrates that lived in agricultural areas treated with DDT were killed off, and few have ever returned.

Stinkpot

The absence of amphibians and reptiles at many sites reveals how poorly we understand the disappearance and lack of recolonization of salamanders, toads, frogs, snakes, and turtles. Being extremely vulnerable to human disturbance, many of these species are among the first to disappear from altered areas, though they are rarely the first to be noticed. When pollutants break down or are flushed out of the environment, plants, invertebrates, birds, and mammals may readily reinhabit previously disturbed areas, largely because of their relatively rapid dispersal rates. Amphibians and reptiles, however, are at a disadvantage when it comes to repopulating areas where they have been eliminated.

Those animals that live in urban areas where the few remaining ponds and woodlots are widely dispersed have been reduced to small, isolated, vulnerable populations. Once extirpated, they have little chance of being reestablished.

Ponds in city parks, for example, are isolated within large urban buffers where they have been protected from agricultural chemicals. Although pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides were widely used in cities in the past, their usage is in decline because of costs and environmental sensitivity. Some cities still use these chemicals, of course, but urban amphibians and reptiles that are able to survive just about anything have managed to survive.

Few species of turtles do well under these conditions, however, and it has come as a surprise to find adult stinkpots and hatchlings in Belvedere Lake in Manhattan’s Central Park. This is the first indication that there might be an urban stinkpot population in the Northeast. One reason musk turtles were always absent from Manhattan is that the island is surrounded by deep water on all sides. They couldn’t get to Manhattan Island because it would have taken far too much energy for these little-legged turtles to continually paddle all the way to the surface for a breath of air. During such a long swim they would have tired and drowned. In some areas, musk turtles will take to deeper water in cold weather, and they will remain on the bottom for months without ever surfacing for air—but not in the Hudson, Harlem, and East rivers. Manhattan’s waterways are largely brackish, and they flow with powerful currents. The turtles couldn’t cross such formidable barriers.

The salt tolerance of local populations of eastern mud turtles (Kinosternon subrubrum) explains their presence in some salt marshes along the East Coast. There are even some in Staten Island, but most urban and suburban populations are doing very poorly.

The stinkpot, like most urban species, is brought into cities such as Manhattan by humans, and then they either escape or are eventually released. Most of the animals that are released in an urban environment do the best they can under the circumstances, but they don’t last long. Few attain their natural life expectancy, and even fewer find others of the same species, mate, and establish a population. In Belvedere Lake, however, the stinkpots seem to have beaten the odds.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation has been considering dredging and expanding Belvedere Lake. Such a move could have a major impact on the musk turtles. Urban ponds are prone to silting in much more rapidly than most ponds and lakes because of the runoff caused by nearby erosion. In this case, the common reed (Phragmites australis) has been invading the shallow waters along the shore and is shading out the new plantings on the bank. By draining the lake and bulldozing the bottom sediments, the park workers would make the lake deeper, temporarily solving the Phragmites problem. In my opinion, it would make more sense to leave the Phragmites alone. The plant is attractive, it provides cover for nesting birds, including red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), and it isn’t bothering anyone. Should the time come when the reed really needs to be controlled, it would be less destructive and possibly more cost-effective to cut it by hand.

In other regions, especially in the South, related species of musk and mud turtles have been maintaining relatively stable populations in man-made bodies of water. In southern Florida the stinkpot, the eastern mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum), and the striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) are doing quite well in a number of urban ponds.

URBAN LIZARDS

Few of the urban lizards in this country are native. The ruin lizard (Podarcis sicula), native to southern Italy, Sicily, and the Lipari Islands, escaped in the 1960s in West Hempstead, Long Island, New York, and is now breeding and established in several Nassau County suburbs, most notably Garden City South, West Hempstead, and Franklin Square. The ruin lizard’s range appears to be restricted to a square kilometer surrounding its initial point of release. The length from the tip of the snout to the end of the tail is almost 10 inches (25 cm). This oviparous (egg-laying) insect-eater is narrow, elongate, and greenish on top.

No one is predicting a rapid increase in numbers of this lizard. Similar cases have not led to rapid range extensions when only a small number of lizards have been released or have escaped. A small population of Podarcis sicula lasted at least 28 years in Philadelphia, though. And in Topeka, Kansas, a small population of green lizards (Lacerta viridis) is still surviving in a busy suburban part of town near a shopping center. These individuals are descendants of lizards that escaped over 30 years ago. The larger specimens get as long as 15 inches (38 cm). The adults are greenish above and whitish below, while the juveniles are brownish with two to four light longitudinal stripes.

Each of these lacertid populations was established by a small number of escaped individuals, but other lizards have been purposely introduced. In 1942, for example, Carl Kauffeld, who was the Curator of Reptiles at the Staten Island Zoo, released 29 fence lizards (Sceloporus undulatus hyacinthus) on Staten Island, in New York City. The lizards had been caught in the Rossville area of the New Jersey pine barrens. By 1960 their numbers had increased, and their range had expanded. This population is now common in several areas of Staten Island, especially where pines are growing on sandy soil. I have heard that additional fence lizards were added later by other collectors; this may have contributed to the overall diversity of the population’s gene pool and increased their chances of survival.

The eastern fence lizard is a member of the largest genus of lizards in North America. There are sixteen species of Sceloporus north of Mexico. This oviparous spiny lizard rarely gets much larger than 8 inches (20 cm) from the snout to the end of the tail. The back is a brownish gray, and each side of the male’s belly has a large patch of blue.

The genus Anolis has more than 300 species living in North America, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America. This is an exceedingly complex assemblage of lizards, and the taxonomy is far from settled. Several different genera have been proposed, but since things are still in flux, I will proceed, using Anolis when referring to species in this group. Only one member, the green anole (Anolis carolinensis), is definitely native to the United States, inhabiting much of the Southeast. Several other species in this “genus” have been introduced to southern Florida where they are now well established and where many of them live in urban areas. The green anole is about 8 inches (20 cm) long, can change colors with its physiological state from green to brown and back again, and has small, almost granular scales. It has a dewlap, or throat fan, which can be extended to reveal the pink color, although some are gray or bluish.

The South American ground lizard (Ameiva ameiva)—a member of the family, Teiidae, which includes 225 species that all live in the Americas—has been introduced to the Miami area, where it is doing well. Ameivas thrive in urban and suburban areas in warmer climates because they are amazingly brazen, quick, and adept at finding and eating just about anything that looks or smells like food. Unlike most other lizards, ameivas readily take foods as wide-ranging as insects, dead fish and mammals, dog food, cat food, and scraps put out for the chickens. The backyards of many homes offer endless opportunities to a small scavenger that comes out in the heat of the day, so the ameiva may have a future in southern Florida where at least two subspecies have been introduced. Both are native to South America.

Southern Florida seems to be one of the major hot spots for introduced lizards in North America. During the past several decades many lizards have become established in Florida’s suburban and urban areas, and some are moving into the more rural areas. For the most part, however, the lizards that are doing well there are those that are more or less confined to human-related habitats. One is the bark anole (Anolis distichus), which was probably introduced from the Bahamas. This anole has a yellow dewlap.

A native lizard that is doing well in some urban areas in southern Florida is the reef gecko (Sphaerodactylus notatus). Like the anoles, geckos have very small, granular scales, but they don’t have a dewlap. The reef gecko grows only 2½ inches (6.4 cm) long. They are brownish to reddish brown, with darker spots that sometimes align in rows.

Living with these species are many others that have been introduced in different ways. The Jamaican giant anole (Anolis garmani), the Puerto Rican lizard (Anolis cristatellus), and the curly-tailed lizard (Leiocephalus carinatus) probably arrived in Florida as stowaways. The Mexican spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura pectinata) probably came in with the animal trade. Lizards that arrived on ships with produce or plants include the green bark anole (Anolis distichus), the brown anole (Anolis sagrei), the yellow-headed gecko (Gonatodes albogularis), the Indo-Pacific gecko (Sphaerodactylus argus), and the ashy gecko (Sphaerodactylus elegans). Lizards that were released by animal dealers or pet owners include the South American ground lizards in both the Hialeah and Suniland populations, the brown basilisk (Basiliscus vittatus), the rainbow lizard (Cnemidophorus lemniscatus), the tokay gecko (Gekko gecko), the green iguana (Iguana iguana) in the airport population, and the Hispaniolan curly-tailed lizard (Leiocephalus schreibersi). Species that were introduced by people not associated with the animal trade are the large-headed anole (Anolis cybotes), the knight anole (Anolis equestris), the curly-tailed lizards (Leiocephalus carinatus) in the Paim Beach population, and the Indo-Pacific gecko (Hemidactylus garnoti) in the South Miami and Coconut Grove populations. The Key Biscayne populations of both the South American ground lizard and the green iguana escaped from the zoo exhibits there, and the Virginia Key population of curly-tailed lizards originated from the exhibits in that city’s zoo.

Native populations of some lizards have been severely reduced in urban areas in southern Florida, although these species are still doing fine in undisturbed areas. These lizards include the six-lined racerunner (Cnemidophorus sexlineatus) and the ground skink (Scincella lateralis). Native species that are widespread in both natural and urban-agricultural areas in southern Florida include the southeastern five-lined skink (Eumeces inexpectatus) and the island glass lizard (Ophisaurus compressus). Exotic species that are doing well in urban and agricultural areas in southern Florida include the knight anole, the Indo-Pacific gecko, the Mediterranean gecko (Hemidactylus turcicus), and the ashy gecko.

The Mediterranean gecko has moved from town to town as a stowaway and is now established in the Gulf states, Texas, Oklahoma, Arizona, and parts of Mexico, as well as on many islands in the Caribbean. These geckos are most often seen on buildings. Another gecko, Mabuya mabouya, which has been very adept at establishing new populations throughout the Caribbean, apparently made the jump to the mainland United States recently. Gregory Pregill, curator of herpetology at the San Diego Natural History Museum, told me that some have been found in trash piles in southern San Diego. There is still no evidence that they are breeding there.

Since most lizards do better in warmer climates, most of the species that have been introduced to the United States are in the southernmost part of the country. It is interesting that southern Florida has a disproportionate number of introduced species. This is probably attributable to several factors. First of all, much of the trade between South America, the Caribbean, and the United States uses ships that pull into ports in southern Florida. Also, Florida has a large Hispanic population. These people travel back and forth between their homes in America and the homes of their friends and family in South America and the Caribbean. And third, because the state is so close to the Bahamas and the Caribbean islands, it is common for vacationers in Florida to take quick trips to the islands. Often people bring “souvenirs” back to Florida, many of which eventually escape or are released. Almost anywhere else in the country these animals’ chances wouldn’t be very good, but southern Florida has a very hospitable climate, and many of the lizards survive. Those that have established populations farther north are all species that live in cooler environments around the world, but these are the exceptions.

Now that so many populations of lizards are found in southern Florida, it may be just a matter of time before some of the lizards travel as stowaways, or by some other means, to additional cities and towns in the South, where they will again escape, or be released, and establish satellite populations. They won’t necessarily spread as rapidly as some introduced species of birds or fish, but in several more decades we may find added diversity in this country’s urban herpetofauna.

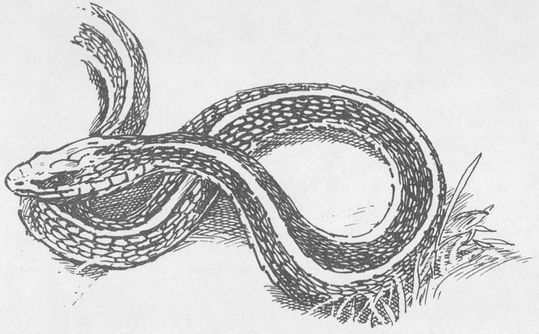

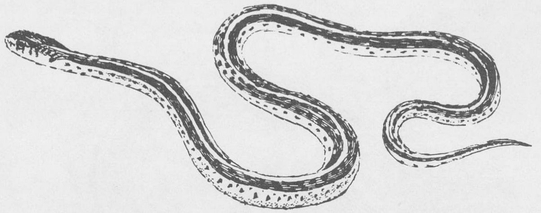

GARTER SNAKE AND BROWN SNAKE

Garter snakes (Thamnophis spp.) range through the northern United States and southern Canada from coast to coast. They comprise some of the most common and numerous snakes in North America. There are thirteen species in this genus in the United States. All have keeled scales, that is, the scales along the back have a ridge down the middle. Most garter snakes have stripes and are variations on shades of brown, yellow, and orange. Populations occupy a wide range of habitats including arid areas, fields, woods, marshes, and stream and river banks. Their ecological versatility is probably related to their widespread occurrence. However, this accounts for only part of the reason that they persist in many densely populated regions where other snakes have not been able to survive. Life history streamlining also appears to account for this persistence. Most reptile populations decline when they are surrounded on all sides by an environment that is difficult to move about in—parking lots, buildings, roads, sidewalks, and other inhospitable structures. For aquatic animals, a body of water can provide a refuge that filters out cars and people. As long as the aquatic species can accomplish all or almost all that is necessary in that body of water, possibly utilizing some adjacent property some of the time as well, they may be able to survive. But terrestrial animals don’t have any barrier between them and us. As a result, they are extremely vulnerable in cities. Most snakes are terrestrial, and few have been able to do well in densely populated regions. Some species have proved to be exceptions, however, the garter snakes among them.

Garter snake

The single most significant preadaptation that appears to account for garter snakes’ ability to survive in urban environments is viviparity: garter snakes do not lay eggs; rather, they bear their young live. This eliminates many complications. Just eliminating the need to find a place to lay their eggs is significant. Cities present formidable obstacles to egg-laying animals, especially those laying eggs on the ground; due to trampling, much urban soil has been compacted over the years so that its bulk density is often greater than that of concrete; the layer of humus is reduced in depth by erosion; and large numbers of rodents patrol the parklands, scavenging anything edible. But viviparity allows the garter snakes to live in such a habitat. If the population can survive on a relatively small plot of land—just large enough for them to feed, mate, overwinter, and bear their young—there is a chance that the snakes will survive.

Young garter snake

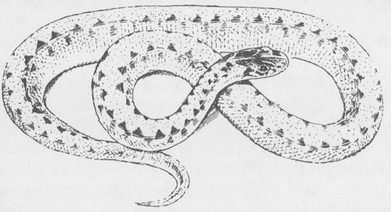

Brown snake

More secretive snakes, those that live under things and those that are small, also seem to have a better chance of surviving in urban environments. One species that fits this description is the brown snake, or DeKay snake (Storeria dekayi), which is small, secretive, doesn’t move much, can maintain a population in a relatively small area, and is viviparous. This is one of the few species that actually does well in some suburbs and even in some cities. Believe it or not, the brown snake is alive and well in New York City. There are enough parks and vacant lots with the right habitat requirements to allow brown snakes to thrive. The food they eat is small and abundant, and they seem to survive being moved around by dump trucks that remove earth and debris—which often contains these small, inconspicuous snakes—from one part of the city, dumping it in another.

Brown snakes are much smaller than garter snakes. The largest brown snake is in the neighborhood of 20 inches (51 cm), though most are considerably smaller. The largest garter snakes can reach a length of 50 inches (127 cm), but most are less that 3 feet (91 cm). The brown snake is usually light brown; some have dots or stripes; and the young have a light ring around the neck. They are sometimes called DeKay snakes because they were named for James DeKay, a 19th-century zoologist.

WATER SNAKE

The northern water snake (Nerodia sipedon) ranges throughout much of the eastern portion of the United States, all the way to the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and south through Kansas to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the East Coast, it is distributed south to North Carolina, where its range continues south, but only inland, through western South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Along the coastal plain from central North Carolina south, this species is replaced by other species of water snakes.

The genus is Nerodia rather than Natrix now, in the more recent parlance of herpetologists (those who study reptiles and amphibians). Depending on the northern water snake subspecies, some have alternating light and dark brown lateral bars along the dorsal surface; others have an indistinct pattern. In many coastal areas the water snake will go into brackish and saltwater, at least temporarily, and will eat any number of different food items, such as fish, frogs, and salamanders. But this snake lives almost exclusively in freshwater habitats in most of its range.

Like the garter snake, this species is widespread and has persisted longer than most other species of snakes in suburbs and some smaller cities; unlike the garter snake, this species seems to have narrower habitat requirements. This may explain why it is not more common in larger cities. It seems that the more urban an area gets, the fewer opportunities exist for species other than a few preadapted, opportunistic animals. Among snakes, this continues to hold true. The water snake, too, is viviparous, which probably is not mere coincidence. Any factor that complicates the life history of an animal will be a strike against its chances for survival in the urban habitats that are available and otherwise suitable.

BRAHMINY BLIND SNAKE

Unlike lizards, which have many established non-native species living throughout the country, only one introduced species of snake is now well established. This is a small worm snake, the Brahminy blind snake (Ramphotyphlops bramina). As a stowaway it has moved to and become established in Australia, Japan, Southeast Asia, Hawaii, and other islands in the Pacific. It is now doing well in suburban Miami.

Because it has moved from port to port with such ease, probably in dirt and packing material, it is difficult to establish its original range, but the Brahminy blind snake is definitely an Old World species. Julian Lee, a professor at the University of Miami, told me that there has been speculation that some of these snakes in Miami may be parthenogenetic, which means that the females do not need males in order to reproduce, and their offspring are all females. If this is so, establishing new populations will be facilitated, since only one individual is needed. Each snake can reproduce on its own, greatly increasing its reproductive capacity. Should it turn out that this species is in fact parthenogenetic, that will be a first for snakes. We know about many invertebrates that can reproduce in such a manner, as well as some fish, amphibians, and lizards; but until now, no snakes are known to have this ability.

Often living submerged in the ground or under things, these small snakes have some of the qualities of the brown snake that preadapt them to survive in urban areas. They eat small amounts of small food items, do not require large spaces, are easily transported unintentionally in earth and debris, and may well expand their range throughout more southern cities and suburbs in this country.