9

MAMMALS

Most people think that few mammals besides rats live in cities, but that is far from true. Mice and rats are among the more successful urban species, however, so reasons for their success will be discussed. Since most of the dominant mice and rats are from Europe and Asia, I will talk about how and when they were introduced and why they are doing so well. I’ll also discuss other successful urban rodents—squirrels, chipmunks, and woodchucks—where they live, how they have survived, and why they are absent from some seemingly suitable urban habitats.

Rabbits, skunks, and bats are other mammals that do well in many densely populated regions around the country. I will explain which species do best, where they live, what they eat, how they are able to survive, and why they are doing better than other species. Cats and dogs are presented because their histories are less well known. When were they domesticated? What led to their domestication? What effects might they have on wild populations of urban species? All of these topics are dealt with.

I’ve also included some marine mammals in this chapter. Not many of them live in cities, but some migrate nearby, and for that reason they are discussed. Humphrey the Whale made headlines in 1985, as did a beluga whale that returned to Long Island Sound a couple of years in a row. Because there is widespread interest in marine mammals, they are discussed in their relation to urban areas.

COMMON HOUSE MOUSE

Many rats and mice that live in close association with people around the world are members of the same family that includes the house mouse (Mus musculus). This group has been lumped with the indigeneous New World rats and mice. Rats and mice belong to the largest mammalian order, Rodentia, which includes about 1,685 species, depending on who’s doing the counting. Many Old World murids have been introduced to other parts of the world. Some have become cosmopolitan in their distribution, living in wild areas, sparsely populated places, rural agricultural regions, and large cities.

The house mouse, originally from southern Asia, is now common throughout the world. Wooded habitats represent unlikely areas for them, but they may be found, along with mouse populations that live in field and along fence-rows, where there is enough cover and minimal environmental disturbance. Of these populations, some live outdoors during the summer and move into buildings during the winter. The forms that live with the completely “wild” populations, neither harming nor helping one another, generally have longer tails and are darker than the wild forms. There are also many domesticated varieties of Mus musculus, the most common of which is an albino. Some strains carry black-and-white patterns; others are various shades of black and gray.

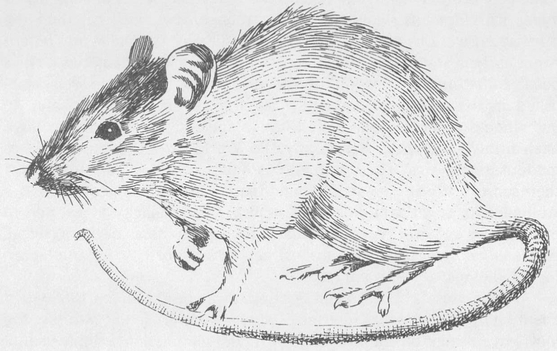

Common house mouse

Wild populations are grayish brown dorsally, with lighter tones underneath. From the tip of their nose to the beginning of their tail they measure from 3 to 3½ inches (7.6 to 8.9 cm) long; the thin scaly tail is about 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10.2 cm) long. These seemingly high-strung little animals leave their calling cards, tiny cigar-shaped black turds, everywhere they go. Adept climbers, they will crawl about on your shelves, in your cabinets, on tabletops, on top of the refrigerator, and they can even walk upright along the electrical cord.

Wild house mice that live outdoors are generally nocturnal, but it is easy to catch them in traps set during the day. While house mice that live indoors also tend to be nocturnal, they readily adapt and are active when there is the least amount of human activity. These mice are able to eat a wide range of foods, including almost any human food. If the household is exceptionally clean, the mice can subsist on some rather bizarre items, such as soap, glue, and paste. In the wild they eat seeds, roots, leaves, and stems. They will also eat insects and some meat when available.

Their nests are made of soft materials. They often make this material by shredding things with their teeth. They eat through many substances, looking for food or nesting material, and in the process can do quite a bit of damage. Considering the things they eat through, sometimes you’d swear they can smell right through plastic bags. This may well be true, considering that the arrangement of molecules in some plastics allows for the diffusion of certain odors.

House mice breed throughout the year, particularly during the warmer months, and may produce more than five litters annually, with three to twelve young per litter. House mice are hardly ever seen, but occasionally their populations increase dramatically. Such “ecological explosions” occurred in the Central Valley of California in 1926-27 and again in 1941-42. Numbers exceeding 82,000 per acre were estimated during one of the worst explosions; in time the numbers decreased to normal levels. Mice can be the hosts of typhus, spotted fever, salmonellosis, and rickettsial pox, and if food is contaminated with their urine or feces, diseases may be spread to humans. However, in most American cities where the majority of diseases carried by house mice are not a major problem, these animals are relatively harmless.

NORWAY RAT AND BLACK RAT

The Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) and the black rat (Rattus rattus), like the house mouse, are murids, members of the group of Old World rats and mice that has been lumped with the New World rats and mice. The genus Rattus contains approximately 78 species. Most live in Southeast Asia and Africa, but many have been introduced elsewhere around the world. Both Norway rats and black rats are quite common in urban areas throughout North America.

Norway rat

The Norway and black rats eat virtually anything they can get their teeth through, but when given a choice, they consume food that gives them a well-balanced diet. Because they eat through things looking for food, they cause considerable damage. Their gnawing doesn’t stop at paper and plastic bags; they will also eat through the insulation around wire and have been known to chew on lead pipes and even concrete dams. The total amount of damage these two species cause each year is estimated to amount to billions of dollars worldwide.

The black rat originally was restricted to Asia Minor and the Orient. It is thought to have been introduced into Europe during the Crusades, although there is reason to believe it may have been in Ireland as early as the 9th century. It then made the vogage to North America on ships of early settlers; one account puts the date at about 1650.

The Norway rat is probably native to eastern Asia and Japan, where it lived along stream banks, and later spread to the rice fields and canals. Unlike the black rat, the Norway rat is more or less confined to areas where the habitat is right for it to build its burrows. It wasn’t until 1553 that Norway rats were first reported in Europe, probably having arrived there on ships. They were first reported in North America around 1775.

Why have these Old World murids been so successful in urban settings? They may have had a jump on American species at adapting to living with humans. Since the house mouse, the black rat, and the Norway rat were living in towns and cities all over the Old World before America had any cities, it stands to reason that when America’s cities began to be built, they would have been the first to become well established in the new environment. They may even have been able to outcompete otherwise well-suited native species. They may also have been firmly established before any Old World rat and mouse diseases made it to America. Their omnivorous habits could account for part of their success. We’ve repeatedly found that omnivory is one of the better strategies for success in cities and suburbs. The capacity to eat and to digest many different types of available food gives these species a considerable edge when foraging on the streets of a major city, in large apartment buildings, or in city parks.

Washington, D.C., has been fighting a war on rats since 1968 when about half of the city was infested. Today, however, James Murphy, the local government official in charge of rodent elimination, estimates only about 4 percent of the city is plagued by rats. Murphy’s staff wages a constant war on the rodent populations. They search the city’s monuments, buildings, and neighborhoods looking for signs of rats, then leave poison pellets in the infested areas. They also educate the public about rat prevention, explaining the importance of storing trash in sealed containers, properly disposing of debris that rats could nest in, and cleaning up dog feces that would otherwise attract rats. The key to avoiding rats is limiting available food.

Those urban parks that have the greatest number of visitors are also likely to have the greatest density of rats. In response, parks departments often pour poison down the rat holes. After many years of this, it may or may not have dawned on park officials that the rats are still alive and well, but many of the chipmunks and other species are long gone.

Rats in some cities have been fed so much rodenticide that the survivors appear to have developed a resistance to chemicals. In New York there is evidence that the effects of some of the newer rodenticides are not altogether unpleasant to the rats. It has, in fact, been suggested that the rats now experience an agreeable high. Robert Angelone, who serves as Central Park’s unofficial rat-reduction strategist, has said it is almost like giving the rats cocaine.

Angelone started testing different rodenticides when New Yorkers complained about the strange daytime behavior of the rats. Rats normally are rather secretive and come out only at night, or when people aren’t around. But some of the chemicals intended to kill the rats were just changing their behavior. Instead of dying, the rats began calmly walking around during the day as if they owned the park. To deal with this new problem, Angelone has begun rotating different poisons; he believes this is killing many of the rats. But no matter what Angelone believes, anyone who goes for a walk in Central Park will see rats brazenly strolling around in the middle of the day.

I’m not entirely sure what all the rat-related hysteria is about. The fear of rats seems to be a learned phobia. Rats are basically just another rodent, without a bushy tail. If we could get over our fear of rats, we might not have to pour so much poison down their holes and endanger so many other animals. Keeping our parks clean would be a less expensive, more effective, and far more attractive method of rodent control.

EASTERN GRAY SQUIRREL

Eastern gray squirrel

The eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) is one of the tree squirrels, a group of about 55 species that ranges over most of Europe, much of Asia, Japan, and the New World from southern Canada to northern Argentina. These animals live in deciduous, coniferous, and tropical forests. The gray squirrel, native to eastern North America, is one of the best-known squirrels in the world. It has been successfully introduced in some cities on the Pacific Coast as well as into Great Britain and South Africa. In certain areas, introduced populations have become pests, damaging crops and trees.

Although gray squirrels are forest dwellers, they often do better in suburbs and cities than in rural forests. There is much food available to them in city parks because people like to feed them and also because people leave edible trash behind. As a result, squirrel populations often expand to densities considerably greater than would be possible in the wild. This sometimes leads to problems, as in Washington, D.C., where some people wanted large numbers of squirrels to be trapped and moved to alleviate the crowded conditions.

Certain species of tree squirrels occur in distinctly different color forms—or morphs—within the same population. A dark morph has been reported in several urban gray squirrel populations in the East, including Rochester, and Albany, New York; Princeton, New Jersey; and New York City. It is hard to understand why these melanistic squirrels have been turning up in cities in the Northeast. If the melanistic squirrel represents a new mutation, how could it have traveled so rapidly between all these cities? And why isn’t it expressed in the intervening regions? It may be that the melanistic gene was always part of the gray squirrel’s genetic repertoire in the Northeast; when it was expressed, those individuals were selected against. Now, with few predators preying on urban squirrels, the dark individuals are not culled from the population. As a result, melanistic squirrels have been increasing in numbers in several urban areas.

Because squirrels come out during the day, much of their behavior includes visual cues. Their long, bushy tails move around in ways that are significant to other squirrels in the area. Being agile and arboreal, they can avoid being run down by dogs and other animals. Squirrels in city parks will search the grass under trees for food while people walk all around them. But when a dog appears in the distance, the squirrels all move to within several feet of the nearest tree trunk, in case they have to make a run for it.

Squirrels collect nuts and bury them in caches within their well-defended territory. When you see squirrels digging through the snow, they may be trying to find the place where they stashed away some nuts during the fall. It is thought that they find these caches by smelling them. Memory may also help, but many of the nuts are never retrieved and appear to have been forgotten. This is why squirrels in the wild are credited with a significant role in reforestation: if the nuts had been left on the forest floor, they might have been consumed by other animals.

During the summer, gray squirrels build large nests of leaves and branches and nestle them into the crotches of trees. In addition to these nests they also enlarge and pad holes in the larger trees. During the winter, even though they don’t hibernate, several squirrels will often hole up together to keep one another warm, and the leaves used to pad the summer nests act as insulation. On warm sunny days during the winter the squirrels often leave their nests to eat, drink, urinate, and defecate. This overwintering behavior is not true hibernation. Animals that hibernate shut their digestive systems down for the winter because their metabolisms slow down so much and their body temperatures become so low that food would only sit inside them and possibly rot. Hibernating animals go into a very deep sleep that is actually physiologically distinct from sleeping.

Squirrels are occasionally seen vigorously chasing other squirrels. Much of this behavior is related to establishing and maintaining their social hierachy. Sometimes they leave scent markings, odors that mark the territory within which they hide their nuts. Any unwanted squirrel within that marked territory may be chased out. Sometimes the chasing is part of their behavior during mating season, which is usually during the middle of winter. It is common to see males chasing females in trees and on the ground, and the males are often seen fighting among themselves over which gets priority in male-female interactions. Winter may not seem like the most appropriate time for such behavior, but, for squirrels, it beats sleeping.

CHIPMUNK

There is only one species of chipmunk in eastern North America. It is the eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus), which lives in southeastern Canada and in most of the eastern half of the United States, except the extreme South.

There are about sixteen species of chipmunk in the West, all of them in the genus Eutamias. They are all difficult to differentiate from one another in the field as well as in the hand. The eastern chipmunk is only about 5 or 6 inches (12.7 to 15.2 cm) long; the tail adds an additional 3 to 4 inches (7.6 to 10.2 cm). They look something like a small, striped squirrel. The tail is bushy and stands straight up when they run about. They always seem slightly high-strung. Their facial stripes, as well as the stripes running the length of their body and ending at the reddish rump, distinguish them from most other species that live within their range.

Eastern chipmunk

Chipmunks are commonly found in deciduous forests with some shrubs in the understory, a few stone walls, and some dead trees. They are largely confined to the ground, but they will climb some trees in search of food. They build burrows that may be as long as 15 feet (4.6 m), extending about 3 feet (91 cm) deep, that contain storage chambers for food to be eaten during the winter when the chipmunks awaken from hibernation. In colder regions, chipmunks may store as many as three gallons of seeds and nuts for the winter. They choose items with a long shelf life. Chipmunks collect other more perishable items, such as fruits, berries, and mushrooms, but they eat them right away.

Least chipmunk

Although common in most suburbs with some woodlots, chipmunks are rarely as common as squirrels in urban areas, perhaps because they need more undergrowth than is generally available in city parks. Since most dead trees and old stone walls have also been removed, many of the important aspects of their preferred habitats are unavailable. Despite these drawbacks, populations of eastern chipmunks have persisted and even thrive in most eastern cities, but they are vulnerable to certain changes. Environmental changes may be important, as well as other factors that could bring chipmunks into direct competition with the Norway rats. In such cases, the rats may win. Another critical factor could be the extensive use of rodenticides to control rats. Pouring poisoned pellets down rodent holes may temporarily decrease the rat population while inadvertently eliminating other non-targeted species such as chipmunks; the result being that those parks with the greatest number of human visitors usually have the worst rat problems, and are now devoid of most other native rodents. One exception is Rocky Mountain National Park, where many people visit each year and leave as much of a mess as people leave anywhere. Yet the chipmunk and ground squirrel (Spermophilus spp.) populations are as healthy as ever. Perhaps the winters there are too harsh for the rats. Without the rats, the National Park Service personnel don’t lay down rodenticides, so the chipmunks around the cabins and the Park Service headquarters are safe. In most suburbs, where rat control measures are not necessary, one finds healthy chipmunk populations.

WOODCHUCK

The woodchuck (Marmota monax), also known as the groundhog, is a member of the genus Marmota, which contains about sixteen species that live in the northern hemisphere, through part of Alaska, most of Canada and the United States, western Europe, and much of Asia. This is the largest-bodied group in the squirrel family, Sciuridae. Six species live in North America; of these the woodchuck probably comes closest to being an urban dweller. It has been included here because it has done well in many areas where people have modified the landscape.

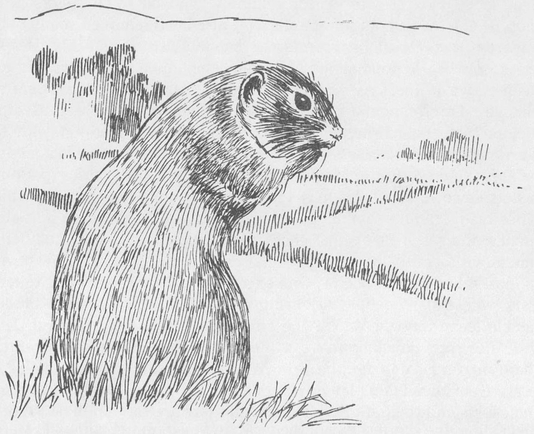

The marmots of North America tend to be western in their distribution, living on talus slopes, often at high elevations, and in valleys. The woodchuck is the only Marmota that lives in the eastern half of the United States. Its range extends into the West, but primarily through Canada. The length from the tip of its nose to the end of its body, excluding its tail, is about 16 to 20 inches (41 to 51 cm); the tail is an additional 4 to 7 inches (10 to 18 cm) long. The body is quite stocky, and the legs are short. On their back the fur is a frosted yellowish brown, the belly is slightly lighter, and the feet are dark brown or black.

Woodchuck

These animals live on the ground, where they dig tunnels that provide a refuge from predators, shelter at night, and a place to rear their young. Since woodchucks and marmots hibernate, the den is where they overwinter. In some areas hibernation can last as long as eight months. After having put on about a half-inch (1.3 cm) of fat under the fur on their backs and shoulders during the summer and fall, they retreat into their burrows, which may be as long as 45 feet (almost 14 m), extending to a depth of 3 to 6 feet (91 to 183 cm). While hibernating, they become torpid, which for woodchucks means their body temperature drops from the normal 99°F (37°C) to somewhere between 37°F and 57°F (3°C to 14°C), and their heartbeat decreases from more than 100 beats a minute to approximately 4 beats per minute. Breathing also slows down to as little as one breath every six minutes.

Woodchucks do best in meadows that have a forest nearby. They used to be found most often in the country living near farms, but now woodchucks are seen on the mowed roadsides along highways, eating the tender plants. It is this preference for young plants that often attracts them to vegetable gardens. In spite of the enmity farmers feel for woodchucks, these animals can be quite beneficial to the animal community. They provide holes and burrows that many other animals use, and their turning of the earth improves the soil structure.

There are at least four woodchucks still surviving right in the middle of Manhattan, in Central Park. The adult, known as Phyllis, raised three young during the spring of 1987. No one knows whether Phyllis is the last descendant of the woodchucks that lived there when the Europeans first arrived or if it is an old animal that escaped from the Children’s Zoo some years ago. But that shouldn’t be the real question; people should wonder where all the other woodchucks went. Considering that Central Park comprises more than 800 acres of suitable woodchuck terrain, several colonies should still be there. Were they deliberately eliminated, or have the years of rat poisons, pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides, as well as the many dogs that are allowed to run loose, all taken their toll? The current park management is quite sane with regard to the use of such toxic chemicals, and they would tolerate a few holes being dug and a little munching here and there—all of which makes me wonder if a reintroduction effort might not make sense.

An American rendition of an older European event has become what we call Groundhog Day. Each year it falls on February 2, when the earth is midway in orbit between its location during the Winter Solstice in December, the shortest day of the year, and the Spring Equinox in March, one of the two days of the year when both day and night last twelve hours. The ancient Celts called February 2 Imbolog, which meant sheep’s milk. To them it was the start of the lambing season. The Celtic tribes thought that if it was sunny, the winter was going to be long; if the day was cloudy, there would be an early spring. The Romans brought Imbolog to the rest of Europe, where the medieval church already celebrated Candlemas on the same day, the Feast of the Purification. When both merged, it used to be said:

If Candlemas be bright and clear

There’ll be two winters in the year.

The original groundhog of Groundhog Day was actually a hedgehog (Erinaceus sp.). Medieval Europeans thought the hedgehog awakened from its winter sleep, walked out of its burrow, and looked for its shadow. Then, knowing how much longer the winter was going to last, it went back to sleep. The concept was carried to North America and adapted to our groundhog. But our groundhogs usually don’t emerge from hibernation until the end of February or early March; they don’t awaken to predict the weather, and its not their shadow they’re looking for. After all those months underground, they want only two things—a meal and a mate.

VIRGINIA OPOSSUM

The Virginia opossum (Didelphis marsupialis) is doing remarkably well around cities, living in the parks and more residential sections. This species has dramatically extended its range northward during the past 100 years. It has spread through the eastern states all the way to Canada. Following its introduction in the western states in the early 20th century, it rapidly spread north and now occurs from Mexico to Canada. Some of this success is attributable to the opossum’s high fecundity, rapid growth, and early maturation. ‘Possums are doing so well, they are even found in all five boroughs of New York City.

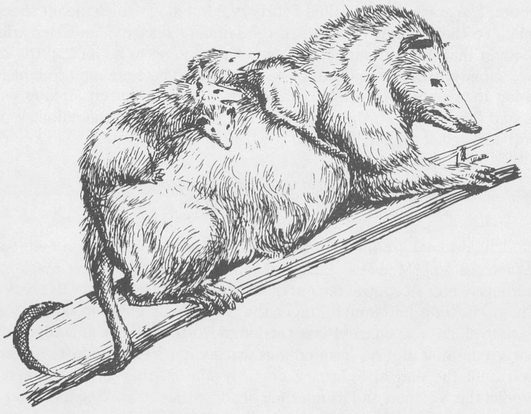

About the size of a cat, though heavier bodied, this long-haired, gray marsupial has a white face, thin black ears, a pointed snout, short legs, an opposable thumb on its hind feet, and a long, round, ratlike prehensile tail. Didelphis means two uteruses, which is a characteristic of these animals. Each uterus has its own cervix, both of which are accommodated by the male’s bifurcated penis.

Virginia opossum

Virginia opossum

Opossums don’t actually hibernate, but they do put on fat in the fall and stay in their dens for days in the winter, going out on occasion. When winter temperatures get very low, ‘possums can get frostbitten and lose the tips of their ears and the ends of their tails.

Because ‘possums are nocturnal, they aren’t seen very often unless they happen to be crossing the road when you’re driving by. In the suburbs, ‘possums are often found dead on the road. That’s partly due to their being nocturnal; many are hit before the driver sees them. It also seems that opposums may go out on the roads at night to clean up other roadkills.

These animals will eat corn, eggs, acorns, nuts, fruits, berries, and the contents of garbage cans. At night they even come up on porches to eat out of a dog’s dish. Their interest in so many types of food makes them well suited to the city and suburbs, where opportunism proves beneficial to many species.

RACCOON

Raccoons are confined to the New World. Seven species are recognized, all of them found from southern Canada to South America. Five of these species live on islands; the other two range over most of the mainland. The raccoon found in North America is Procyon lotor. Like many other mammals that do well in urban and suburban areas, the raccoon is more active at night than during the day.

Holes are important to raccoons. They need places to hole up during the day, and cities have plenty of suitable locations. Many raccoons use sewer pipes, culverts, and drainage pipes. They travel through pipes to get from one area to another. For instance, there may be a marsh on one side of the road and a woodlot on the other, so a culvert becomes their chief route back and forth. This passageway allows them to stay out of sight and to avoid the cars.

Cars are a significant predator. Few people think of them as such because they are inanimate, but cars are among the chief annihilators of wildlife in densely populated regions. Species with low reproductive rates may not be able to survive a rather high level of depredation, and therefore are usually the first to be eliminated from a region when roads are put through. While birds can fly over the cars, most mammals, reptiles, and amphibians are considerably more vulnerable. Therefore, using pipes, culverts, and sewers to get from one side of the road to another has proved extremely advantageous to certain species.

Raccoon

Raccoon

Raccoons tend to do best near a wetland. They like to patrol the water’s edge where any number of different feeding opportunities present themselves. Their omnivory allows them to eat seeds, nuts, fruit, grain, fish, frogs, and rodents. The well-known raccoon habit of washing their food before eating it is more common among captive animals than it is in the wild. Apparently they wash their prey to remove grit and to wash off the distasteful or toxic secretions that are released by some species of salamanders, frogs, and toads.

Their winter dormancy is tied to low temperatures and is relatively brief. In the North, this behavior is a valuable adaptation that does not occur among raccoons in the South. This is one of several species that do well aroung campsites throughout the country. Raccoons seem to be sufficiently opportunistic to seize the advantage of food left out overnight or tossed into trash cans. Their opportunism may account for some of their success in cities and suburbs.

RABBIT

Rabbits, hares, and pikas are all members of the mammalian order Lagomorpha. Rabbits were until recently thought to be rodents, but biochemical studies have shown that the two groups have no close relationship. Lagomorphs do have some similarities to various groups of hoofed animals, but the precise relationships need to be worked out. The two North American species of pikas—small, rabbitlike mammals with short ears—are seldom found near people, living only in remote, high elevations. Although pikas live above the timberline in inhospitable environments, they do not hibernate, which shows that some small mammals can get through a harsh winter without going into torpor.

Eastern cottontail rabbit

The other six genera of lagomorphs, including the rabbits and hares, are all in the family Leporidae. They live in a wide range of habitats on most major land masses. Members of the family have been introduced to Sumatra, New Zealand, Austrailia, and to many smaller islands around the world.

Of all the species in the rabbit and hare family in North America, the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) probably has the widest range and comes in contact with the greatest number of people. These rabbits are found throughout the eastern two-thirds of the United States, with the exception of the northernmost portion of New England. The New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis) also lives in the East, but usually at higher elevations than the eastern cottontail. The two species are virtually impossible to positively distinguish in the field and are difficult to tell apart in the hand. The eastern cottontail is the species most often found in backyards or eating the new sprouts in your vegetable garden. These rabbits do well in suburbia and are found in every borough of New York City, where they live in the parks and some of the more suburban areas. Some cottontails even live in the northern part of Central Park. In more rural areas, birds of prey probably represent their most significant predator, but in cities and suburbs cars and dogs take the largest toll.

Rabbits generally feed during the evening, any time from dusk to dawn. When crossing roads, they can be disoriented by headlights, and many are run over. Although they grow rapidly and breed continuously, producing as many as seven broods a year, with several young per litter, mortality rates are rather high, and the average lifespan is less than a year.

Eastern cottontail

A crate of a western species of hare broke open while being unloaded at Kennedy Airport in New York several years ago, and the escapees have established a successful breeding colony near the runways. To date this is the only location where hares exist in the city, and there is no reason to believe they are spreading. However, because many rabbits are kept in captivity, there have been ample opportunities for others to escape and establish new populations. The main difference is that, compared to a whole crate of rabbits, one escaped individual is rarely enough to lead to a successful population. A non-native population has become established in the Northwest, where eastern cottontail pets escaped. Their descendants now live wild in western Washington State. Another escaped population lives on San Juan Island, off the Washington coast, where the rabbits have been destructive to the habitat due to their high numbers. This species is the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Often such populations of non-native species can prove extremely detrimental, but the San Juan rabbits have been useful as prey for the local bald eagles.

SKUNK

The disagreeable substance that skunks emit from their scent glands is their primary form of protection. It is so effective that people and other animals give skunks a wide berth. As a result, they spray only on rare occasions. When they do spray, it is only after they have given ample warning, and it is never without provocation. Even then, their spray doesn’t travel very far, so you’d have to be almost on top of a skunk to get hit. Since they don’t do any harm, other than the occasional rabid skunk, and seldom spray anyone, there is little reason to fear them. Most of the skunks we smell are those that have been run over.

Several species live in North America north of Mexico. By some counts there are six, but odds are better that there are only four; a couple of species probably are only geographic variants that don’t merit status as separate species. The four distinct species fall into three groups, which are recognized as distinct genera. These are Spilogale, which is the spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius); Conepatus, the hognose skunk (Conepatus leuconotus); and Mephitis, which includes two species, the striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) and the hooded skunk (Mephitis macroura). The spotted skunk is black with a white spot on the forehead, a white spot under each ear, and four broken, irregular white stripes down the neck, back, and sides. The tip of the tail is also white. The spotted skunk is several inches shorter than the other species which range from about 12 to 19 inches (30 to 48 cm) long from the tip of the nose to the end of the body, excluding the tail, which is usually almost as long as the body. The hognose skunk has a naked, elongate snout. Its back and tail are entirely white and the lower sides, legs, and belly are black. The striped skunk has a narrow white stripe right down the middle of the forehead, and a broad white area on the back of the neck that divides into two white stripes, forming a V at the shoulders; each of these stripes goes back along the sides to the tail. The hooded skunk appears as either of two different color morphs, with intermediate variants. One is almost entirely white; the other is nearly all black except for two white stripes along the sides.

The spotted skunk is found through much of the United States from the Pacific Northwest to Pennsylvania and south to the southern tip of Florida. The striped skunk is even more widely distributed; it ranges through most of southern Canada and all of the lower 48 states. The hooded skunk is confined to southern Arizona and New Mexico and south through Mexico; the hognose skunk is also confined to the Southwest, parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

The striped skunk is most likely the species that comes into contact with the greatest number of people, although sometimes you might see a spotted skunk at night by a campsite. The varied diet of all skunks consists of fruit, berries, green plants, insects, grubs, amphibians, eggs (especially turtle eggs), young birds, small rodents, carrion, and garbage. Skunks can’t climb, and their dens are always on the ground, either in other animals’ holes or under buildings, which can bring them into contact with people. Also, since their diet is so varied, they are prime candidates for living near people, since the more omnivorous species are among those that do best around humans.

Most dogs, cats, and children know enough to give skunks the right of way, so they rarely have to bite, run, or spray. Some animals make the mistake of getting too close to a skunk, but they seldom make the same mistake a second time. Because nothing wants to bother a skunk, it is not unusual to see them walking about as if they hadn’t a worry in the world. Those that get run over may be hit because the headlights are disorienting, or the motorist may not see them until it is too late. Because skunks have such a bad reputation, however, they aren’t welcome in most densely populated areas, but many smaller cities and suburbs across the country have relatively large skunk populations.

BIG BROWN BAT

The big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) is only one of the approximately 900 bat species found throughout the world, representing nearly 25 percent of the 3,800 species of mammals. Mexico, with more than 300, has more species of bats than any other country. North of Mexico there are about 40 species. The big brown bat is probably the most widespread, though possibly not the most numerous. Another common and widespread species is the little brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus). Some cavedwelling species are so abundant at specific caves that they may outnumber other species found in the rest of the country.

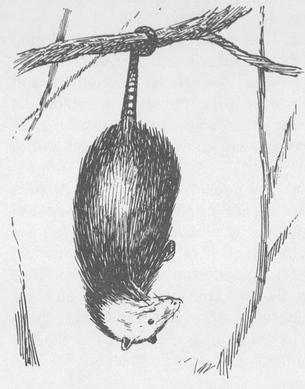

Bats are very difficult to identify on the wing, as well as in the hand, but in flight, the big brown bat can be distinguished from other native species by its relatively large size. They are 4 to 5 inches (10.2 to 12.7 cm) long and have a wingspan of about 12 inches (30 cm). Their steady, directed flight is also distinctive. This is usually the bat seen flying around street lights in cities and suburbs, where they are attracted to insects drawn by the light. Many bats that live in urban areas seek shelter nearby, roosting during the day beneath roof overhangs or in enclosed, protected areas where they are secluded from other species, particularly people.

Some species of bats fly through the woods; others fly out in the open; still others prefer to fly over streams or marshes. Some species eat nectar, fruit, blood, and frogs or fish, in addition to insects. Most of the bats found in North America feed on insects caught in flight. The big brown bat tends to feed while flying fairly high over open areas such as meadows, fields, and water.

For years, bats have been maligned or unappreciated, but a recent push to change their image came about as a result of the detrimental effects of stories about vampires, rabies, and bats getting caught in people’s hair, all of which were either blatantly false or greatly exaggerated. The image campaign seems to be helping. People are actually starting to put up bat houses, which are similar to bird houses. Evidently these people know that the number of caves and other good roosting sites has declined over the years due to development, so the bats now need man-made habitats. Bats do keep down the numbers of mosquitoes and other insects, actually consuming as many as 3,000 insects a night, so even people who aren’t particularly enlightened may feel bats are worth protecting; yet many bat species are declining in numbers to the point of being endangered. It is hoped that the innovative bat houses will take hold and prove helpful. These large wooden structures are closed on the top and the sides, but the bottom is open; the inside has crevices where the bats can hang on. Bat houses are constructed with inner slats that can be moved and arranged to suit the size of the local species. The open bottom allows bats to enter, but it keeps out other species, such as birds, mice, and squirrels, which might otherwise use the bat house as a nest box. Bat Conservation International is now selling bat houses and pushing the profits back into the organization, which has its headquarters at the University of Texas in Austin.

Little brown Myotis

Big brown bat

FOX, WOLF, COYOTE, DOG

Foxes, wolves, and coyotes are wild dogs native to North America. Each has suffered markedly from human encroachment, mostly because farms presented opportunities that were too great for the animals to pass up in terms of the relatively easy prey represented by the penned-up chickens, turkeys, ducks, goats, sheep, and other domestic animals. Coming in direct competition with farmers has never been the best way for an animal to earn a living. In most instances, if a farmer so much as suspects an animal of reducing his profits, he kills it. Hundreds of years of such run-ins have pushed some of these animals to the brink of extinction. Most have been extirpated from entire regions.

Coyote

Both the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus ) still persist in many suburbs and even in some remote parts of major cities, though they are seldom seen in New York City anymore. In London, there are areas where foxes are reported to be doing quite well. Foxes are very shy, always two steps ahead of any human in the area, but every once in a while one will be seen. A sighting usually comes as a big surprise to residents, who never dreamed that foxes lived in their area. One reason foxes are seen so infrequently is that they are active primarily at night.

The gray wolf (Canis lupus) has been almost entirely eliminated from the southern 48 states, though it is doing well in some parts of Alaska. The red wolf (Canis niger) is one of the most endangered mammals in North America. Until recently it was still seen infrequently in a few southern areas, but now the last 75 animals are all being held in captivity where they are being bred. Soon, if all goes according to schedule, breeding pairs of red wolves will be released from their holding pens in North Carolina in a first step to reintroduce this species to the East.

The coyote (Canis latrans) was once earmarked by the U.S. government for total elimination, and the results of this policy were disastrous through much of its range. Coyotes once roamed from Alaska through the western states of Mexico, though they were not present in most eastern states. Interestingly, recent accounts of coyotes from many areas in the Northeast show that this species has moved into areas where it has never lived before. Apparently the void left by the extirpation of the gray wolf opened up opportunities that the coyote has been able to exploit. Competition from wolves defending their territory probably excluded coyotes from the East until the wolves were eliminated. However, the coyote that had begun to move into the Northeast is not identical to that of several hundred years ago. All species in the Canis genus are closely related and can interbreed without difficulty. That is what has been happening in many areas where coyotes and red wolves occurred together. As a result, the differences between the two, which were slight to begin with, have become even more nebulous. Coyotes have also been mating with domestic dogs, resulting in hybrids referred to as coydogs. Coyotes and gray wolves are not nearly as tolerant of each other, however; where the two overlap, the coyote usually moves on elsewhere.

Coyotes used to be restricted to areas west of the Mississippi, but they may now be in all the eastern states. The same adaptability and opportunistic behavior that brought them into conflict with farmers has proved an asset in non-farm areas. They occur in just about every habitat this country has, from forests to deserts, and from mountains to the shore. Unlike most other North American mammals, this species seems to be able to survive almost anywhere, even in many suburbs. Positive identification is not always easy once they have lived near densely populated areas for a while, because that’s where mixing with domestic dogs becomes common. As a result, it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between a pet dog, a feral dog, a coydog, a coyote, a hybrid of a coyote, and a red wolf.

The importance of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) in urban and suburban areas should not be underestimated. While the wild dogs have suffered mercilessly from human brutality, domestic breeds have been the beneficiaries of human kindness, shelter, and companionship. In exchange, dogs give friendship and loyalty. All they require is a meal a day and an occasional romp outside. But during that romp they will, if allowed to run loose, chase down practically anything that moves, or that smells. The result is not just a lot of scared animals, but a lot of dead animals. When unleashed, man’s best friend is a powerful predator, probably one of the most destructive predators in suburbs and city parks.

Even though dogs are domesticated, they still have a substantial amount of the wild animal in them. What’s worse, unlike wild predators such as bobcats (Lynx rufus) and coyotes, unleashed dogs will chase down deer at an alarming rate, killing as many as seven or eight in a day. The problem is especially bad when spring comes to some regions where whitetail deer (Odocoileus virginianus) have made it through the winter but are hungry and weak. These deer often fall victim to packs of family pets that are allowed to run loose. In Vermont, game wardens are empowered to shoot dogs seen chasing deer, a powerful incentive for lazy owners to exercise their pets properly—by walking them on a leash.

Dogs haven’t always been domesticated. Putting a precise date on when their domestication actually began is difficult because the bones of wolves, jackals, and early domestic dogs are not easy to differentiate. There is some evidence that dogs were already domesticated by the late Paleolithic period. It is believed that domestication began when people took in pups, which were easily raised in captivity. The people soon became fond of these new pets, which were friendly and good natured. Dogs are social animals. When raised with people rather than other dogs, they develop a bond with their captors that is not unlike the bond they might have formed with individuals of their own species.

Canids may have been initially taken in, just as the young of many other species that are brought home from time to time, but given the success of these animals, generations have been raised in close contact with people. In time, the dogs came to depend on their human companions for food, and as the relationship grew, dogs began to perform tasks that made them helpful to their owners—hunting, herding, guarding, and so forth—strengthening the dog-human bond.

Domestic dogs are generally thought of as a distinct species, but it should be kept in mind that they descended from the many species of Canis that people came into contact with over a period of thousands of years. With over 55 million pet dogs in the United States, an estimated two-thirds of which are eventually abandoned, problems associated with feral dogs do not appear to be about to decline unless something is done to reduce the amount of pet mismanagement.

CAT

Unlike the dog, which has been living in association with people as a domesticated animal for as much as 12,000 years and has the distinction of being the animal with by far the longest history of domestication, the domestic cat (Felis catus) is a relative newcomer to captivity. This could be part of the reason why so many people still believe that cats are independent. Part of that misperception is more closely related to the inherent differences between animals in the dog family and those in the cat family. Social structure and behavior differ markedly.

Domestic cat

With the development of agriculture, fields of grain began to attract granivores, such as rodents. These animals in turn attracted small members of the cat family in the genus Felis. Later, grain was stored in vast quantities for use between harvests. These storage areas, too, attracted large, unwelcome rodent populations. The wild cats helped control these rodents, and for this they were valued; in some cultures, notably Egypt, they were revered.

There is evidence from 4,300 years ago that the Egyptians already had a domestic cat, but this date has not been generally agreed on. Some scientists place the date for the earliest domestication of the cat at 3,200 years ago. Cats spread from Egypt to other countries, where domestication continued. In each host country the domestic breed hybridized with the local wild cat. The European wild cat (Felis silvestris), which is found through Europe and Asia Minor, hybridized with the domestic breed when the Egyptian variety was brought north. Tame cats bred with the wild cats in each region until the breed became a mixture that appears to have races of many different species. Some breeds have considerably more of one species than another. For instance, the domesticated Persian cat is thought to contain genes from the Pallas or steppe cat (Felis manul).

In some parts of the world, cats have reverted to a more wild type after having gone feral. Many of these feral populations have been extremely detrimental to local populations of other species. For instance, many islands in the South Pacific that previously lacked any mammalian predators now have cats that thrive on birds that breed there. Only those birds that can defend their nests have been able to survive; many of the other species are no longer found breeding on any of these islands. Off New Zealand, the Stephen Island wren (Xenicus lyalli) was discovered in 1894, and during the same year the lighthouse keeper’s cat drove it to extinction.

Suburbs and cities have pet and feral cats that roam at will and play an important role in the current structure of urban ecosystems. New York City alone has approximately 300,000 pet cats. If only a small percentage of those cats escape, are released, or are allowed to come and go as they please, they could have a significant effect on the local species. If we then add in the cats that are already feral, the number of predaceous cats is even more impressive.

WHALES AND PORPOISES

The marine mammals include whales, porpoises, walruses, seals, sea lions, and sea otters. Few of these mammals live in urban areas, but because whales are occasionally seen in densely populated regions, I will briefly mention them here.

In addition to an occasional stranding near a city or town, whales and porpoises regularly pass by many urban centers during their spring and fall migrations. In some areas, small industries have grown up around whale-watching. Boatloads of whale-watchers go out of Cape Cod and Montauk, Long Island. For information, contact the Okeanos Ocean Research Foundation in Hampton Bays, New York. On the West Coast, migrating gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) have been a tourist attraction for years. People go out in boats to watch as approximately 11,000 grays migrate along the coastline between their summer feeding grounds off Alaska and their winter breeding lagoons along the shores of Baja California. During the migrations, boats regularly leave points along the coast. Some of the best towns to leave from are Mission, San Diego, Monterey Bay, San Pedro, and Redondo Beach. A good place to see whales from shore is at Point Reyes Lighthouse north of San Francisco.

Humphrey the Humpback Whale made headlines in October 1985 and drew crowds in California. Humpbacks feed in the Alaskan waters during the summer, then head south for the winter. For some reason, Humphrey left the normal course on the way south. Instead of continuing along the coast, the huge whale swam under the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco Bay. Television crews soon appeared, and Humphrey’s trip inland made the network news. Almost 70 miles from the ocean, Humphrey finally stopped at the Cache Slough, and stayed there.

Concerned citizens and scientists wanted to get Humphrey back to the Pacific. They organized a flotilla of boats, and they banged pipes trying to get Humphrey back on course. It took some work, but eventually they got the whale to swim back underneath the Cache Slough Bridge, but Humphrey stopped at the Rio Vista Bridge. Thinking the noise from the traffic might have confused the whale, the people stopped traffic, raised the drawbridge, and banged on pipes until Humphrey went under the bridge. But again the whale stopped and refused to go any farther.

Finally, some biologists brought recordings of the sounds that whales make when they are feeding. This ploy worked. The whale followed the sound equipment back to the bay and eventually out into the ocean. Then, in August 1986, Humphrey was seen again, migrating back down the coast, having survived the ordeal without making the same mistake twice. Humpbacks also migrate close to the East Coast each year and can be seen from whale-watching boats.

There was another whale rescue with a similar happy ending not too long before the Humphrey episode. About 3,000 white beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas), representing approximately 10 percent of the entire world population, got trapped in the Senyavina Strait of the Bering Sea when their escape route froze over, making it impossible for them to get out without suffocating. In time their opening in the ice was also going to freeze over, killing the belugas. The Soviet Union sent an icebreaker to cut an escape route, but the whales couldn’t be persuaded to take it until the Russians began playing recorded music full-blast from the deck. Jazz didn’t work, but classical music is said to have lured the belugas, and they followed the icebreaker to safety.

Another beluga was in the news two years in a row. During the summers of 1985 and 1986, a white beluga stayed near the Connecticut shore where people got to know it and even swam with it. Again in 1986, at the beginning of the summer, it returned along the shore, and people saw it frequently. Then one day the whale washed ashore perforated with bullet holes. Apparently some boaters had used the beluga for target practice.

For several years in a row, a beluga was sighted along Fire Island, a barrier island off the south shore of Long Island that is the home of a summer resort community.

Beluga whales are well adapted to arctic conditions, where they live and breed in great numbers. It is not known why they usually remain in more northern waters, considering that they also appear to do well in warmer waters. It may be partly because of the competition in the more southern waters from established species such as harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena), harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), and gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) in the coastal waters, and white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus), white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), pilot whales (Globicephala melaena), and other species in the offshore waters. Sharks, which are more numerous in the warmer waters, could also play a role in limiting the whales’ range to northern waters. Or maybe their pinkish color makes them more vulnerable to the stronger solar radiation in the more southern waters.