[New Zealand Canoes, Houses, etc.]

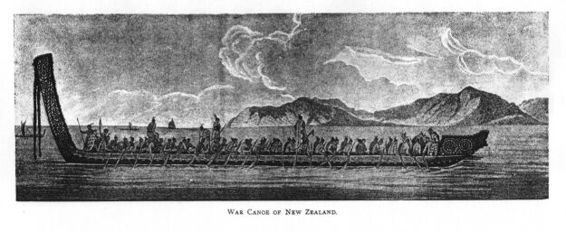

The people shew great ingenuity and good workmanship in the building and framing their boats or Canoes. They are long and Narrow, and shaped very much like a New England Whale boat. Their large Canoes are, I believe, built wholy for war, and will carry from 40 to 80 or 100 Men with their Arms, etc. I shall give the Dimensions of one which I measured that lay ashore at Tolago. Length 68 1/2 feet, breadth 5 feet, and Depths 3 1/2, the bottom sharp, inclining to a wedge, and was made of 3 pieces hollow'd out to about 2 Inches or an Inch and a half thick, and well fastned together with strong platting. Each side consisted of one Plank only, which was 63 feet long and 10 or 12 Inches broad, and about 1 1/4 Inch thick, and these were well fitted and lashed to the bottom part. There were a number of Thwarts laid a Cross and Lashed to each Gunwale as a strengthening to the boat. The head Ornament projected 5 or 6 feet without the body of the Boat, and was 4 feet high; the Stern Ornament was 14 feet high, about 2 feet broad, and about 1 1/2 inch thick; it was fixed upon the Stern of the Canoe like the Stern post of a Ship upon her Keel. The Ornaments of both head and Stern and the 2 side boards were of Carved Work, and, in my opinion, neither ill design'd nor executed. All their Canoes are built after this plan, and few are less than 20 feet long. Some of the small ones we have seen with Outriggers, but this is not Common. In their War Canoes they generally have a quantity of Birds' feathers hung in Strings, and tied about the Head and stern as Additional Ornament. They are as various in the heads of their Canoes as we are in those of our Shipping; but what is most Common is an odd Design'd Figure of a man, with as ugly a face as can be conceived, a very large Tongue sticking out of his Mouth, and Large white Eyes made of the Shells of Sea Ears. Their paddles are small, light, and neatly made; they hardly ever make use of sails, at least that we saw, and those they have are but ill contrived, being generally a piece of netting spread between 2 poles, which serve for both Masts and Yards.

The Houses of these People are better calculated for a Cold than a Hot Climate; they are built low, and in the form of an oblong square. The framing is of wood or small sticks, and the sides and Covering of thatch made of long Grass. The door is generally at one end, and no bigger than to admit of a man to Creep in and out; just within the door is the fire place, and over the door, or on one side, is a small hole to let out the Smoke. These houses are 20 or 30 feet long, others not above half as long; this depends upon the largeness of the Family they are to contain, for I believe few familys are without such a House as these, altho' they do not always live in them, especially in the summer season, when many of them live dispers'd up and down in little Temporary Hutts, that are not sufficient to shelter them from the weather.

The Tools which they work with in building their Canoes, Houses, etc., are adzes or Axes, some made of a hard black stone, and others of green Talk. They have Chiszels made of the same, but these are more commonly made of Human Bones. In working small work and carving I believe they use mostly peices of Jasper, breaking small pieces from a large Lump they have for that purpose; as soon as the small peice is blunted they throw it away and take another. To till or turn up the ground they have wooden spades (if I may so call them), made like stout pickets, with a piece of wood tied a Cross near the lower end, to put the foot upon to force them into the Ground. These Green Talk Axes that are whole and good they set much Value upon, and never would part with them for anything we could offer.* (* The weapons of greenstone, found in the South Islands, were much prized. This hard material required years to shape into a mere, or short club, and these were handed down from father to son as a most valuable possession.) I offer'd one day for one, One of the best Axes I had in the Ship, besides a number of Other things, but nothing would induce the owner to part with it; from this I infer'd that good ones were scarce among them.

Diversions and Musical instruments they have but few; the latter Consists of 2 or 3 sorts of Trumpets and a small Pipe or Whistle, and the former in singing and Dancing. Their songs are Harmonious enough, but very doleful to a European ear. In most of their dances they appear like mad men, Jumping and Stamping with their feet, making strange Contorsions with every part of the body, and a hideous noise at the same time; and if they happen to be in their Canoes they flourish with great Agility their Paddles, Pattoo Pattoos, various ways, in the doing of which, if there are ever so many boats and People, they all keep time and Motion together to a surprizing degree. It was in this manner that they work themselves to a proper Pitch of Courage before they used to attack us; and it was only from their after behaviour that we could tell whether they were in jest or in Earnest when they gave these Heivas, as they call them, of their own accord, especially at our first coming into a place. Their signs of Friendship is the waving the hand or a piece of Cloth, etc.

We were never able to learn with any degree of certainty in what manner they bury their dead; we were generally told that they put them in the ground; if so it must be in some secret or by place, for we never saw the least signs of a burying place in the whole Country.* (* The burying places were kept secret. The body was temporarily buried, and after some time exhumed; the bones were cleaned, and hidden in some cave or cleft in the rocks. As bones were used by enemies to make implements, it was a point to keep these depositories secret, to prevent such desecration.) Their Custom of mourning for a friend or relation is by cutting and Scarifying their bodys, particularly their Arms and breasts, in such a manner that the Scars remain indelible, and, I believe, have some signification such as to shew how near related the deceased was to them.

[Maori and Tahiti Words.]

With respect to religion, I believe these people trouble themselves very little about it; they, however, believe that there is one Supream God, whom they call Tawney,* (* Probably Tane-mahuta, the creator of animal and vegetable life. The Maori does not pray.) and likewise a number of other inferior deities; but whether or no they worship or Pray to either one or the other we know not with any degree of certainty. It is reasonable to suppose that they do, and I believe it; yet I never saw the least Action or thing among them that tended to prove it. They have the same Notions of the Creation of the World, Mankind, etc., as the people of the South Sea Islands have; indeed, many of their notions and Customs are the very same. But nothing is so great a proof of their all having had one Source as their Language, which differ but in a very few words the one from the other, as will appear from the following specimens, which I had from Mr. Banks, who understands their Language as well, or better than, any one on board.

[Speculations on a Southern Continent.]

There are some small differance in the Language spoke by the Aeheinomoweans and those of Tovy Poenammu; but this differance seem'd to me to be only in the pronunciation, and is no more than what we find between one part of England and another. What is here inserted as a Specimen is that spoke by the People of Aeheinomouwe. What is meant by the South Sea Islands are those Islands we ourselves Touched at; but I gave it that title because we have always been told that the same Language is universally spoke by all the Islanders, and that this is a Sufficient proof that both they and the New Zelanders have had one Origin or Source, but where this is even time perhaps may never discover.

It certainly is neither to the Southward nor Eastward, for I cannot perswaide myself that ever they came from America; and as to a Southern Continent, I do not believe any such thing exist, unless in a high Latitude. But as the Contrary opinion hath for many Years prevail'd, and may yet prevail, it is necessary I should say something in support of mine more than what will be directly pointed out by the Track of this Ship in those Seas; for from that alone it will evidently appear that there is a large space extending quite to the Tropick in which we were not, or any other before us that we can ever learn for certain. In our route to the Northward, after doubling Cape Horn, when in the Latitude of 40 degrees, we were in the Longitude of 110 degrees; and in our return to the Southward, after leaving Ulietea, when in the same Latitude, we were in the Longitude of 145 degrees; the differance in this Latitude is 35 degrees of Longitude. In the Latitude of 30 degrees the differance of the 2 Tracks is 21 degrees, and that differance continues as low as 20 degrees; but a view of the Chart will best illustrate this.

Here is now room enough for the North Cape of the Southern Continent to extend to the Northward, even to a pretty low Latitude. But what foundation have we for such a supposition? None, that I know of, but this, that it must either be here or no where. Geographers have indeed laid down part of Quiros' discoveries in this Longitude, and have told us that he had these signs of a Continent, a part of which they have Actually laid down in the Maps; but by what Authority I know not. Quiros, in the Latitude of 25 or 26 degrees South, discover'd 2 Islands, which, I suppose, may lay between the Longitude of 130 and 140 degrees West. Dalrymple lays them down in 146 degrees West, and says that Quiros saw to the Southward very large hanging Clouds and a very thick Horizon, with other known signs of a Continent. Other accounts of their Voyage says not a word about this; but supposing this to be true, hanging Clouds and a thick Horizon are certainly no signs of a Continent--I have had many proofs to the Contrary in the Course of this Voyage; neither do I believe that Quiros looked upon such things as known signs of land, for if he had he certainly would have stood to the Southward, in order to have satisfied himself before he had gone to the Northward, for no man seems to have had discoveries more at heart than he had. Besides this, this was the ultimate object of his Voyage.* (* It is conjectured that what Quiros saw was Tahiti, but his track on this voyage is very vague. There are certainly no islands in the latitude given except Pitcairn.) If Quiros was in the Latitude of 26 degrees and Longitude 146 degrees West, then I am certain that no part of the Southern Continent can no where extend so far to the Northward as the above mentioned Latitude. But the Voyage which seems to thrust it farthest back in the Longitude I am speaking of, viz., between 130 and 150 degrees West, is that of Admiral Roggeween, a Dutchman, made in 1722, who, after leaving Juan Fernandes, went in search of Davis's Island; but not finding it, he ran 12 degrees more to the West, and in the Latitude of 28 1/2 degrees discover'd Easter Island. Dalrymple and some others have laid it down in 27 degrees South and 106 degrees 30 minutes West, and supposes it to be the same as Davis's Isle, which I think cannot be from the Circumstance of the Voyage; on the other hand Mr. Pingre, in his Treatise concerning the Transit of Venus, gives an extract of Roggeween's Voyage and a map of the South Seas, wherein he places Easter Island in the Latitude of 28 1/2 degrees South, and in the Longitude of 123 degrees West* (* Easter Island is in longitude 110 degrees West, and is considered identical with Davis' Island.) his reason for so doing may be seen at large in the said Treatise. He likewise lays down Roggeween's rout through those South Seas very different from any other Author I have seen; for after leaving Easter Island he makes him to steer South-West to the height of 34 degrees South, and afterwards West-North-West. If Roggeween really took this rout, then it is not probable that there is any Main land to the Northward of 35 degrees South. However, Mr. Dalrymple and some Geographers have laid down Roggeween's track very different from Mr. Pingre. From Easter Isle they have laid down his Track to the North-West, and afterwards very little different from that of La Maire; and this I think is not probable, that a man who, at his own request, was sent to discover the Southern Continent should take the same rout thro' these Seas as others had done before who had the same thing in View; by so doing he must be Morally certain of not finding what he was in search of, and of course must fail as they had done. Be this as it may, it is a point that cannot be clear'd up from the published accounts of the Voyage, which, so far from taking proper notice of their Longitude, have not even mentioned the Latitude of several of the Islands they discover'd, so that I find it impossible to lay down Roggeween's rout with the least degree of accuracy.* (* Roggeween's track is still unknown.)

But to return to our own Voyage, which must be allowed to have set aside the most, if not all, the Arguments and proofs that have been advanced by different Authors to prove that there must be a Southern Continent; I mean to the Northward of 40 degrees South, for what may lie to the Southward of that Latitude I know not. Certain it is that we saw no Visible signs of Land, according to my Opinion, neither in our rout to the Northward, Southward, or Westward, until a few days before we made the Coast of New Zeland. It is true we have often seen large flocks of Birds, but they were generally such as are always seen at a very great distance from land; we likewise saw frequently peices of Sea or Rock Weed, but how is one to know how far this may drive to Sea. I am told, and that from undoubted Authority, that there is Yearly thrown up upon the Coast of Ireland and Scotland a sort of Beans called Oxe Eyes, which are known to grow no where but in the West Indies; and yet these 2 places are not less than 1200 Leagues asunder. Was such things found floating upon the Water in the South Seas one would hardly be perswaided that one was even out of sight of Land, so apt are we to Catch at everything that may at least point out to us the favourite Object we are in persuit of; and yet experiance shews that we may be as far from it as ever.

Thus I have given my Opinion freely and without prejudice, not with any View to discourage any future attempts being made towards discovering the Southern Continent; on the Contrary, as I think this Voyage will evidently make it appear that there is left but a small space to the Northward of 40 degrees where the grand object can lay. I think it would be a great pity that this thing, which at times has been the Object of many Ages and Nations, should not now be wholy be clear'd up; which might very Easily be done in one Voyage without either much trouble or danger or fear of Miscarrying, as the Navigator would know where to go to look for it; but if, after all, no Continent was to be found, then he might turn his thoughts towards the discovery of those Multitude of Islands which, we are told, lay within the Tropical regions to the South of the Line, and this we have from very good Authority, as I have before hinted. This he will always have in his power; for, unless he be directed to search for the Southern lands in a high Latitude, he will not, as we were, be obliged to go farther to the Westward in the Latitude of 40 degrees than 140 or 145 degrees West, and therefore will always have it in his power to go to George's Island, where he will be sure of meeting with refreshments to recruit his people before he sets out upon the discovery of the Islands.* (* Cook carried out this programme in his second voyage, when he set at rest for ever the speculation regarding the Southern Continent.) But should it be thought proper to send a Ship out upon this Service while Tupia lives, and he to come out in her, in that case she would have a prodidgious Advantage over every ship that hath been upon discoveries in those Seas before; for by means of Tupia, supposing he did not accompany you himself, you would always get people to direct you from Island to Island, and would be sure of meeting with a friendly reception and refreshment at every Island you came to. This would enable the Navigator to make his discoveries the more perfect and Compleat; at least it would give him time so to do, for he would not be Obliged to hurry through those Seas thro' any apprehentions of wanting Provisions.

[Tupia's List of Islands.]

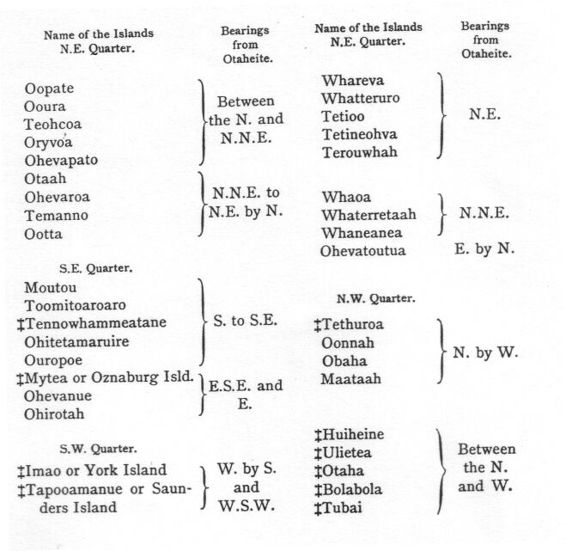

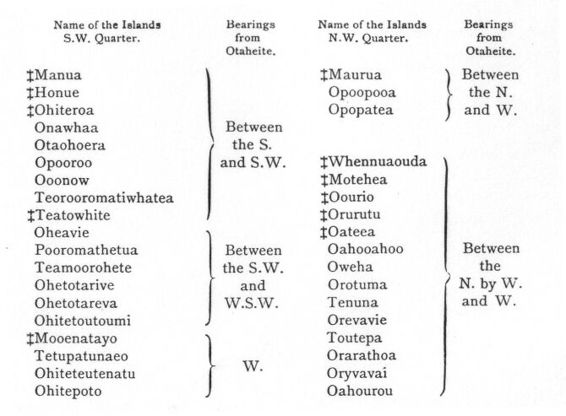

I shall now add a list of those Islands which Tupia and Several others have given us an account of, and Endeavour to point out the respective Situations from Otaheite, or George's Island; but this, with respect to many of them, cannot be depended upon. Those marked thus (*) Tupia himself has been at, and we have no reason to doubt his Veracity in this, by which it will appear that his Geographical knowledge of those Seas is pretty Extensive; and yet I must observe that before he came with us he hardly had an Idea of any land being larger than Otaheite.

The above list* was taken from a Chart of the Islands drawn by Tupia's own hands. (* This list is hopeless. With the exception of the Society Group (Huiheine, and the names that follow), Imao (Eimeo), Tapooamanuo, Tethuroa, and Ohiteroa, all lying near Tahiti, none can be recognised. Those north and east are no doubt names of the Paumotu Group, low coral islands, disposed in rings round lagoons, whose innumerable names are very little known to this day, and very probably the Tahitians had their own names for them.) He at one time gave us an account of near 130 Islands, but in his Chart he laid down only 74; and this is about the number that some others of the Natives of Otaheite gave us an account of; but the account taken by and from different people differ sencibly one from another both in names and numbers. The first is owing to the want of rightly knowing how to pronounce the names of the Islands after them; but be this as it may, it is very certain that there are these number of Islands, and very Probably a great many more, laying some where in the Great South Sea, the greatest part of which have never been seen by any European.

[Historical Notes on New Zealand.]

NOTES ON NEW ZEALAND.

As already stated by Cook in the Journal, New Zealand was first discovered by Abel Tasman, a Dutch navigator, in the year 1642. Sailing from Tasmania, he sighted the northern part of the Middle island, and anchored a little east of Cape Farewell in Massacre (Golden) Bay, so called by him because the Maoris cut off one of his boats, and killed three of the crew.

Tasman never landed anywhere, but coasted from Massacre Bay along the western side of the North Island to the north point. He passed outside the Three Kings, and thence away into the Pacific, to discover the Friendly Group.

No European eye again sighted New Zealand until Cook circumnavigated and mapped the islands.

The warlike character of the natives is well shown in this Journal. On nearly every occasion they either made, or attempted to make, an attack, even on the ships, and in self-defence firearms had constantly to be used. Nevertheless, Cook's judgment enabled him to inaugurate friendly relations in most places where he stopped long enough to enable the natives to become acquainted with the strangers.

It was not so with other voyagers. De Surville, a Frenchman, who called at Doubtless Bay very shortly after Cook left it, destroyed a village, and carried off a chief. Marion de Fresne was, in 1772, in the Bay of Islands, killed by the natives, with sixteen of his people, and eaten, for violation of some of their customs, and illtreatment of some individuals.

Other outrages followed, committed on both sides, and it is no wonder that, though Cook represented the advantages of the island for colonization, it was not considered a desirable place in which to settle. The cannibalism of the Maoris especially made people shy of the country.

Intermittent communication took place between New Zealand and the new Colony of New South Wales, and at last, in 1814, Samuel Marsden, a clergyman of the Church of England, who had seen Maoris in New South Wales, landed in the Bay of Islands with other missionaries. This fearless and noble-minded man obtained the confidence of the Maoris, and a commencement of colonization was made.

It was not, however, until 1840 that the New Zealand Company was formed to definitely colonize. They made their station at Wellington.

In the same year Captain Hobson, R.N., was sent as Lieutenant-Governor. Landing first at the Bay of Islands, he transferred his headquarters to the Hauraki Gulf in September 1840, where he founded Auckland, which remained the capital until 1876, when the seat of Government was transferred to Wellington.

The North Island, in which all these occurrences took place, contained by far the greater number of the natives, and it seems strange now that the first efforts to settle were not made in the Middle Island, which has proved equally suitable for Europeans, and where the difficulties of settlement, from the existence of a less numerous native population, were not so great. It is not necessary here to follow the complicated history of New Zealand in later years, which unfortunately comprises several bloody wars with the Maoris.

The present prosperous condition of this great colony is well known, but it has not been effected without the rapid diminution of the natives, who have met with the fate of most aborigines in contact with Europeans, especially when the former were naturally bold and warlike.

The Maoris have retained the tradition of the original arrival of their race in a fleet of canoes from a country called Hawaiki, which is by some supposed to be Hawaii in the Sandwich Group. As we have seen, the language was practically the same as that of Tahiti, and there is no doubt that they came from some of the Polynesian islands. The date of the immigration is supposed to be the fifteenth century.

Each canoe's crew settled in different parts of the North Island, and were the founders of the different great tribes into which the New Zealanders were divided. The more celebrated canoes were the Arawa, Tainui, Aotea, Kuruhaupo, Takitumu, and others.

The Arawa claimed the first landing, and the principal idols came in her. One of these is now in the possession of Sir George Grey. A large tribe on the east coast still bears the name of Arawa, and her name, that of the Tainui, and other of the canoes, are now borne by some of the great steamships that run to New Zealand.

Cook, in the voyage with which we have to deal, completely examined the whole group. His pertinacity and determination to follow the whole coast is a fine instance of his thoroughness in exploration. No weather nor delay daunted him, and the accuracy with which he depicted the main features of the outline of the islands is far beyond any of the similar work of other voyagers. It is true that he missed in the south island many of the fine harbours that have played such an important part in the prosperity of the Colony; but when we consider the narrowness of their entrances, and the enormous extent of the coast line which he laid down in such a short time, this is not astonishing.

His observations on the natives and on the country display great acuteness of observation, and had the settlers displayed the same spirit of fair treatment and respect for the customs of the natives, much of the bloody warfare that has stained the annals of the Colony might have been averted; though it is scarcely possible that with such a high-spirited race the occupation of the islands, especially the North island, where the majority of the Maoris were, could have taken place without some disturbances.

New Zealand now contains 630,000 Europeans, and 41,000 Maoris. Its exports are valued at 10,000,000 pounds, and the imports at 6,250,000 pounds. There are 2000 miles of railways open. Such is the result of fifty years of colonization in a fertile and rich island, the climate of which may be described as that of a genial England.