Chapter 2

The Rebirth of Ruins

What is the antique in Rome if not a great book whose pages have been destroyed or ripped out by time, in which each day modern research fills in the blanks and bridges the gaps?

—Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy

At the beginning of his account of the Peloponnesian Wars, in a remarkable moment of prolepsis, Thucydides warns that if one day we were to compare the ruins of Sparta and Athens, the viewer would falsely deem Athens to be twice as powerful because of her splendid temples and public edifices. Monumental architecture is not always a reliable guide to a city’s true power: “the greatness of cities,” the Greek historian writes, “should be estimated by their real power and not by appearances.”1 Thucydides believes his work—an ergon—will give a more accurate account of Athens’s rise and fall, more complete and truthful than any physical monuments.2 Along with his predecessor Herodotus, he inaugurated the idea of history as lasting for all time—aei—so that generations might be edified by the lessons of the past.

Reprising the monumentality of written history, Livy remarks in his preface that the Roman past should “be set in illustrious monument,” in inlustri posita monumentum (1.10–11). Like the architectural achievements of Augustus, Livy’s work will be a reminder to future ages of the noble deeds of the Romans. The imperial reconstruction project created an urban topography in which the built environment—palaces, temples, fora, baths, obelisks, inscriptions, statues, trophies, gardens—were the material coordinates that instantiated the ideology of power.3 In Livy’s work too cityscape, narrative, mental topography, and enargeia intersect to form the ideology of his text.4 The Roman historian in this sense creates a reality of the text by amplifying, reducing, and crystallizing the reality of the city.

Ruins sometimes lie, but not those of Rome; she occupies a singular locus in our cultural memory, for the city and her ruins are coextensive. Ovid went so far as to claim that “the land of other nations has a fixed boundary, but the space of the city of Rome is the space of the world” (Fasti 2.684). If ancient historians had their moments of prolepsis, imagining their cities in ruins, Renaissance humanists had many moments of analepsis, imagining Rome in her complete glory. “How Rome was, her ruins themselves teach,” Roma quanta fuit, ipsa ruina docet, was a Renaissance commonplace (to be discussed later). In chapter 1 we saw how the poetics of ruins emerged in the Renaissance from the millennium-long desire for immortality and how it was expressed in the transmigration of languages from antiquity to the sixteenth century. Writers thought that their craft was superior to monuments of mere stone and marble, so they turned their documents into monuments.5 We now move from the study of words to the study of things in order to consider the physicality of ruins—how monuments turned to documents. In this chapter I argue that the idea that material ruins could be objects of empirical knowledge not only was born in the Renaissance, but it defined the period as such. We will also see how Rome, the proverbial palimpsestic city, came to be written and rewritten upon. The identity of the Eternal City perdured in its temporal mutations and representations, surviving multiple displacements and spoliations. In this way the Renaissance became the Ruin-naissance.

The Beauty of Ruins

The revival of antiquity that began in full force in the late fourteenth century was concomitant with a new understanding of the ruins of Rome. Jacob Burckhardt writes that the dilapidated city “awakened not only archaeological zeal and patriotic enthusiasm, but an elegiac or sentimental melancholy.”6 The broken monuments underscored with haunting pathos the vast gulf between the time of humanism and antiquity and made observers realize just how irretrievably lost the classical past was.7 In 1398 Pier Paolo Vergerio lamented, “Rome, once the center of the world, is now nothing but a name and a legend.”8 Manuel Chrysoloras wrote to the Byzantine emperor in 1411, “Even these ruins and heaps of stones show what great things once existed, and how enormous and beautiful were the original constructions. For what in Rome was not beautiful?”9 So too Alberto degli Alberti to Giovanni de’ Medici in 1443: “The modern things here are in a very sorry state, the things that have fallen are Rome’s beauty.”10 For the first time in the postclassical world, the ruins of antiquity were seen as beautiful, an aesthetic phenomenon, something deserving of wonder.

In his letter Vergerio reported, “It is often said, and with some foundation in truth, that in ruined cities—those which have been destroyed by some violent act, or those that have been gnawed away by old age—the air is not healthy.”11 The intermingling of urban trash and architectural collapse gave rise to the popular belief that the city was pervaded by a noxious miasma. In 1420, when Pope Martin V returned to Rome after a long exile in Avignon, “he found it so dilapidated and deserted,” according to Bartolomeo Platina in Lives of the Popes (1479), “that it bore hardly any resemblance to a city. Houses had fallen into ruins, churches had collapsed, whole quarters were abandoned and the town was neglected and oppressed by famine and poverty.”12 The population lived in dwellings little better than huts; the Pantheon was a stockyard, the Forum a pig market; horses ambled around the Column of Trajan; sheep roamed over at least four of the Seven Hills; and the Tiber flooded during the seasonal rains. It was little more than a provincial village, with barely twenty thousand residents, whereas at its greatest, in the late imperial period, the caput mundi had had a population of more than one and a half million.13

So writes Cristoforo Landino (1424–98):

Et cunctis rebus instant sua fata creatis

Et, quod Roma doces, omnia tempus edit.

Roma doces olim tectis miranda superbis,

At nunc sub tanta diruta mole iaces.

Heu, quid tam Magno, praeter sua nomina, Circo

Restat, ubi Exquilias sola capella colit?

Nec sua Tarpeium servarunt numina montem,

Nec Capitolinas Iuppiter ipse domos.

Quid Mario, Caesar, deiecta trophaea reponis,

Si quod Sylla fuit, hoc sibi tempus erit?

alta quid ad coelum, Tite, surrigis amphitheatra?

Ista olim in calcem marmora pulchra ruent.

Nauta Palatini Phoebi cantaverat aedes,

Dic tua, dic Phoebe, nuc ubi templa manent?

Heu, puduit statuas Scopae spectare refractas,

Haec caput, ista pedes, perdidit illa manus.

Nec te, Praxiteles, potuit defendere nomen,

Quominus ah, putris herma, tegaris humo;

Hanc nec Phidiaca vivos ostendere vultus

Arte iuvat: doctus Mentor ubique perit.

Quin etiam Augusto Stygias remeare paludes

Si licet et vita rurus in orbe frui,

Inquirens totam quamvis percursitet urbem,

Nulla videre sui iam monumenta queat.14

Fate weighs down on all things created, Rome, you teach how time devours all things. Rome, you teach how once you were renowned for your high roofs, and now you lie underneath a great pile of ruins. O what remains of the Circus Maximus, except in name, when only a lone she-goat pays homage to the Esquiline? No longer is the Tarpeian Rock guarded by her gods, nor does Jupiter dwell in the Capitoline. Why Caesar, do you take up Marius’s cast-off trophies, now that time will be for him [the enemy that] Sulla once was? Why, Titus, do you build your high amphitheater up to the skies? Those once-beautiful marbles are melted down into lime. The sailors once sung of Apollo’s Palatine Temple. Tell me, Apollo, where is your temple now? Oh, it was shameful to see the broken statues of Scopas—one has lost its head, this one its feet, that one its hands. Scarcely, Praxiteles, could your name defend you, so that oh, you putrid herm, would no longer be covered with earth. Nor does Phidian art help him show living faces; Learned Mentor everywhere perishes. Even if Augustus could come back from the shores of the Styx, even if he could return to earth to live again, if he goes searching over the city he would not find any of his own monuments.

To the humanist, the monuments of Rome—dilapidated and neglected—presented themselves as the illegible remnants and hidden repositories of the ancient world. Landino’s catalogue of pleading questions underscores a commonplace of the period: the difference between the Rome that was and the Rome of now only heightens the inexorable course of history and the decay of time. From inert rubble the ruin is elevated from lowly mass to lofty metaphysics, its stony silence aspiring to a sublime philosophy of history. In its material substance and allegorical significance, the ruin became a true “symbol.” This word—from syn (together) and bole (a throwing, a casting, the stroke of a missile, bolt, beam)—originally meant “a pact,” “an agreement,” or “a token torn in two.”15 The ruin is such a sundered object. In 1796 the French archaeologist Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy would ask, “What is the antique in Rome if not a great book whose pages have been destroyed or ripped out by time, in which each day modern research fills in the blanks and bridges the gaps?”16 But already, at the dawn of humanism, the vestiges of the classical city had been figured as a network of effaced signs, a text that was alternately legible or indecipherable.

Spolia

As scholars from Rodolfo Lanciani to Salvatore Settis to Maria Fabricius Hansen have argued, the ruins of Rome were the result not of foreign invasion but of spolia, the practice of exploiting older structures for building materials.17 Since ruins evoked little nostalgia in medieval discourse, their constitutive parts—columns, capitals, entablatures, friezes, doors—could be wrested from their original whole, transposed to any building, and made to inhabit new identities. Participating in a living trade that circulated the old amid the new, marmorarii (marble cutters) and calcararii (lime burners) flourished as they pillaged the city’s material remains. From at least the first to the seventeenth century much of Roman architecture was constructed from recycled marbles. The heads of classical statues were replaced with those of Christian saints; sarcophagi were disinterred for Christian burial; ancient cinerary urns were turned into stoups for holy water in churches.

Certainly spoliation happened for pragmatic reasons; the quality of ancient materials was very high. But theologically builders literalized Augustine’s metaphor in De doctrina christiana: “Just as the Egyptians had not only idols and graven images which the people of Israel detested and avoided, so also they had vases and ornaments of gold and silver and clothing which the Israelites took with them secretly when they fled, as if to put them to a better use.”18 As the Old Testament “prefigured” the New, so did the marble of classical culture analogically pave the way for Christianity. Spolia is a material and metaphorical translatio—a transfer from one place to another as well as one discourse (pagan) to another (Christian). One can see how this is a material analogue to the literary practice of imitation, citation, and allusion. As fragments of ancient texts were incorporated into the new textual body, architectural parts from old temples and pagan monuments found new life in ecclesiastical buildings. The fragments of defunct pagan temples are to be submitted to the edifice of the new religion, so that a consecrated house of God becomes the spatial realm in which the sundry materials of the saeculum are united into the mighty architectonics of faith.

Almost two centuries after Augustine, Pope Gregory (ca. 540–604) boldly transposes Augustine’s appropriation. He instructs the missionaries to Britain, “The idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed with holy water, altars set up in them, and relics deposited there. . . . We hope that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may abandon their error and, flocking more readily to their accustomed resorts may come to know and adore the true God.”19 Though the legends of Gregory consigning the Palatine library to flames and abolishing antique statues in Rome itself were wildly exaggerated, these myths were perpetuated polemically by humanists from Boccaccio to Ghiberti to Vasari.20 The material remains of antiquity became the ground of contentions twice over; first the early Christians considered them to be idols and thus wanted them destroyed, then Renaissance humanists valued them and mourned their obliteration. Tommaso Laureti’s 1585 Triumph of Christianity in the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican perfectly illustrates this cultural ambivalence; a muscular classical statue, beheaded and dismembered, falls prostrate at the feet of a smaller crucifix (Plate 2). Though the idol has been laid low, the entire action takes place in a richly marbled classical interior, as if the Counter-Reformation builders had followed Gregory’s directive to cleanse and consecrate the space to the glory of God.

Because ancient remnants were used primarily for instrumental purposes, before the Renaissance they were rarely studied on their own terms. Arnaldo Momigliano, in his classic “Ancient History and the Antiquarian,” writes, “The Middle Ages did not lose the classical interest in inscriptions and archeological remains. Inscriptions were occasionally collected. Monuments were noticed. What was lost, notwithstanding the reminder contained in St. Augustine’s Civitas Dei, was the Varronian idea of ‘antiquitates’—the idea of a civilization recovered by systematic collection of all the relics of the past.”21 The genre of medieval guidebooks to Rome, mirabilia, confirms Momigliano’s insight. These travel itineraries were interested in the surviving monuments not as documents of history but as sites of pilgrimage. The steady flow of pilgrims to the Holy City created a need for reliable itineraries to the main churches and famous sites. Instead of presenting “the idea of a civilization recovered by systematic collection of all the relics of the past,” the guidebooks presented the idea of faith as experienced by the systematic visiting of all Roman churches that contained the relics of the saints. The anonymous author of the twelfth-century Mirabilia urbis Romae does record their surviving inscriptions and archaeological remains but is more interested in the material riches of sites: “How great was their beauty in gold, silver, brass, ivory, and precious stones.”22

Enigma

How is knowledge through Rome’s physical monuments possible? Armando Petrucci’s masterful study Public Lettering examines the way Rome, the epitome of the “written city,” embodied its ideology and civic memory in the inscriptions on its busts, bas-reliefs, colonnades, triumphal arches, baths, circuses, theaters, and imperial residences.23 But throughout the millennia, especially in the Middle Ages, weathering, neglect, and vandalism made many monuments virtually impossible to decipher. Monumental epigraphy, Petrucci notes, had all but ceased in medieval Rome; the art of the elegant incised Latin capitals was lost.

Master Gregorius’s twelfth-century Narracio de mirabilibus urbis Romae is a case in point. Discovered in 1917, it survives as a single manuscript in St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge. The work is important because it stands between the tradition of mirabilia, medieval guidebooks on Rome for pilgrims, and the more accurate humanist treatises. Master Gregorius describes what he sees, supplemented by knowledge drawn from history and local authorities (he has a fairly good working knowledge of Lucan and Virgil, quoting them ten times), but on the whole his accounts lean toward the fanciful and legendary. He makes some attempts at awareness of historical accuracy, acknowledging that much has been lost. In the final lines the contingencies of form and content merge: “On this tablet I read much, but understood little, for they were aphorisms, and the reader has to supply most of the words.”24 Even so, the remainder of the folio page is cut off: there is only a small slip at the top. The verso is blank.

Gregorius’s confession underscores the hermeneutic difficulty of deciphering material monuments. The enigma of inscriptions is also present eight hundred years earlier in a late antique poem of Ausonius (ca. 310–395):

Lucius una quidem, geminis sed dissita punctis

Littera: praenomen sic nota sola facit.

Post M incisum est: puto sic non tota videtur;

Dissiluit saxi fragmine laesus apex.

Nec quisquam, Marius, seu Marcius, anne Metellus

Hic iaceat, certis noverit indiciis.

Truncatis convulsa iacent elementa figuris,

Omnia confusis interiere notis.

[Miremur periisse homines? monumenta fatiscunt,

Mors etiam saxis nominibusque venit.]

Lucius is one letter, but it is separated by twin points: in this way a single sign indicates the praenomen. After an “M” is inscribed, at least I think [it] is—it is not all visible. The top has been damaged by the stone breaking and has fallen off, nor could anyone know through certain clues whether a Marius, a Marcius, or a Metellus lies here. The letters lie disturbed with their shapes truncated, all have perished in a confusion of signs. [Are we surprised that men die? Monuments gape apart, death comes even to stones and names.]25

These verses are remarkable for they present the uncertain process of epigraphic decipherment as the shape of the poem itself. It begins with the specific problem of textual decipherment—the weight of a single letter, “M”—and expands to a general gnōmē on the transitory nature of all things: “death comes even to stones and names.” The visible and the invisible intersect while the weathered monument maintains a minimal legibility. Reading its scripts becomes a matter of conjecture, moving from the perceived (the “M”) to the imagined (“a Marius, a Marcius, or a Metellus”).

The poem’s Nachleben too mirrors its message. Don Fowler notes that modern editors differ in the placement of the last two lines, since the last four verses appear as a separate poem in some manuscripts, whereas in the oldest it is part of a preceding epitaph.26 This is most ironic, for the very lines that lament the erasure of stones and names themselves have been ravaged. The difficulty of deciphering inscriptions in Ausonius and Master Gregorius raises an epistemological problem that would later become fundamental to the humanists: How much of the past is really knowable?

This aporia is also expressed in one of the earliest extant Anglo-Saxon poems, “The Ruin,” where all signs of inscriptions have been erased, leaving only inscrutable detritus. Since this poem is preserved in the so-called Exeter manuscript within the genre of riddles, it leaves the reader to construct meaning out of enigmas:

Wondrous is this stone-wall, wrecked by fate;

The city-buildings crumble, the works of the giants decay.

Roofs have caved in, towers collapsed,

Barred gates are broken, hoar frost clings to the mortar,

Houses are gaping, tottering and fallen,

Undermined by age. The earth’s embrace,

Its fierce grip, holds the mighty craftsmen;

They are perished and gone. This wall, grey with lichen

And red of hue, outlives kingdom after kingdom,

Withstands tempests; its tall gate succumbed.

The city still moulders, gashed by storms.27

Scholars conjecture that the site described is Bath. At the time of the poem’s composition, circa 975, the Romans had been gone from England for three hundred years already.28 Thus to the anonymous author of this poem that vanished culture was but a dim myth.

In his 1911 essay “The Ruin,” Georg Simmel writes that architecture illustrates the struggle between “the soul in its upward striving and nature in its gravity.” The ruin is a result of “collaboration” between human and the world: “Nature has transformed the work of art into material for her own expression as she had previously served as material for art.”29 A thousand years separate the Old English poem and the German sociologist’s insight, but they both share a concern with how ruins embody a dialectic between art and nature.30 The unknown tenth-century author devotes as much time to describing the works of nature as to describing the works of man, observing the inevitable dissolution of artifacts to their biological and geological origins. Imagining the bright days when the “mead-hall was filled with delights,” he laments that the ingenuity of these unknown makers, crafting the impressive “well-wrought” walls, “showershield,” and “high arch,” are finally overcome by the humble persistence of “the earth’s embrace,” “grey with lichen, red of hue.” Unlike his Renaissance successors, this anonymous writer does not proclaim the power of poetry to transcend the ravages of time. The fact that the manuscript itself is a badly damaged fragment—seared by a diagonal burn mark—only underscores the poet’s message of mortal futility.

What is striking about Master Gregorius, Ausonius, and the author of “The Ruin” is that their very message about loss and erasure is mirrored in their fragmentary material form. Thus they might serve as coordinate points on which we can map the late antique and medieval ways of grappling with the instability of material inscriptions. Let me add an intriguing cross-cultural analogue. There is a traditional Chinese hanging scroll that beautifully resonates with these examples. I am thinking of Master Li Cheng’s (919–67 CE) famed Reading the Stele (Plate 3). The scene depicts a desolate landscape with a faded stele (bei), framed by an enormous grove of trees painted in the “dragon claw” style, their branches contorting, twisting, in a struggle against the sky for their survival, along with two small figures, an elderly gentleman on horseback and his attendant holding a staff. Like Simmel and the Exeter “Ruin,” Li’s composition establishes a set of proportions between man, art, and nature: the stele towers over the diminutive humans, and the tree branches encroach on and overwhelm the stele. Sinologists have long debated the painter’s intention: Does it represent a particular object, a particular figure, a particular historical event?31 What is inscribed on the stele has also prompted much discussion. From the men’s facial expressions, the stele presents an utter enigma. Yet unlike Master Gregorius or Ausonius, reading is not just difficult, it is impossible, for there is no inscription at all—the stele is wordless, completely blank. The art historian Wu Hung compellingly argues that its empty surface is intentional, for it dramatizes the travelers’ alienation in encountering an anonymous past.32 Thus from a Chinese vantage Reading the Stele offers a compression of the Roman problems of erasure, memory, and representation into the cipher of a blank tablet.

Before and After

Let us return to Europe. To understand the emergence of the ruin as a distinct category of discourse, we risk reifying two historical periods—the medieval and the Renaissance—as autonomous cultural systems. Of course the fourteenth- and fifteenth-century humanists’ distinctions between themselves and their predecessors have been replicated in many ways by those who study them today.33 In the past generation there has been much scholarly debate about whether such periodization expresses a definite break or masks a continuity.34 The ruin, denoting persistence and rupture, perhaps becomes a cipher of both.

Though depictions of ruins were, to be sure, not completely absent in the medieval period, as the examples above demonstrate, they were less common and differed in emphasis. In Dante ruina merely means “landslide” (Inf. 23.137). When ruins do appear in the visual tradition, they usually teach lessons of morality. Maso di Banco’s Life of St. Sylvester (ca. 1341, Church of Santa Croce, Florence) depicts the taming of a dragon in the Roman Forum (fig. 2). The fresco contains clear depictions of collapsed walls and rubble, but, with the exception of one lone Ionic column, there is no classicizing impulse or nostalgia for what has been destroyed. Likewise Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government (ca. 1338–40, Palazzo Publico, Siena) juxtaposes a flourishing city with a desolate one, but the message the painting conveys is that this city has been rightfully destroyed and there is no desire for recovery (Plate 4).35 The aftermath does not really matter; the important thing is the destruction itself. Or consider the scenes of ruination in illuminated manuscripts: the fall of cities such as Babylon or Jericho is depicted at the moment of collapse, with tumbling men, beasts, and stones suspended in midair (fig. 3). Medieval scribes were much more interested in rendering ruins as spectacles of present destruction than as retrospective scenes of destruction’s aftermath.

Figure 2. Maso di Banco, from The Life of St. Sylvester, , ca. 1341. Fresco, Bardi di Vernio Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence. Scala/Art Resource, New York.

With the perils of periodization firmly in mind, we can nevertheless say that the European fascination with ruins came into being near the beginning of what we now call the Renaissance. Perhaps no other genre illustrates the stark differences between medieval and Renaissance perceptions of the ruin more than its emergence in Quattrocento Adoration and Nativity paintings.36 In early Trecento examples, such as the Nativity panel of Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà altarpiece in Siena (ca. 1308–11), there is little emphasis on architectural features (fig. 4). Mary and the infant Jesus are enveloped within an inconspicuous manger, itself enfolded in a grotto, the former a typical motif of the Northern European Gothic style and the latter found in Byzantine manuscript illuminations.37 In contrast, Sandro Botticelli’s late Quattrocento The Adoration of the Magi (ca. 1478–82) demonstrates a renewed interest in antiquity with the unmistakable prominence of a classical structure in its perspectival center (Plate 5).38 No longer housed in a cave, the once humble manger is transformed into an impressive Doric structure of three rows of smooth rectilinear columns bearing a broken entablature on which a gabled wooden roof rests, all in accordance with the rules of axial symmetry. A broken brick wall stands behind the Holy Family. In the background, barely visible and slightly off center, the bluish-gray spires and dome of a Gothic church protrude; in the foreground rest scattered pieces of rocks, the leftover shards, perhaps, of some catastrophe; on the sides are structures in various stages of decomposition with vegetation sprouting around them.

The temporalities of nature and artifact are intertwined in the painting; the ruins signify the collapse of pagan culture while also foreshadowing the death of Christ. The scene in some ways resembles a cantiere, a construction site. The cycle of architectural works in progress and works in ruins corresponds to the various stages of nature in the painting: the ruins on the left are covered in dead branches and twigs; on the right there is flourishing verdant growth. The wooden roof in the center suggests either a scaffold or a frame for the permanent structure to come; the stones on the ground suggest potential building materials. In these distinct architectural and seasonal units we see the entire trajectory of architectural life, from the elements of nature that serve as raw construction materials to architecture’s humble beginnings in wood, from noble marble edifices to, finally, their reversion to their origins. The painting thus circulates from purpose to obsolescence, from design to destruction. All these elements can be interpreted as the history of Christianity allegorically mapped onto the history of architecture—a history, as Joseph Ryk-wert argues, that is a slow progress from the primitive hut of Adam and Vitruvius to an unfinished triumphant classical structure that is now used as a sacred edifice.39

Figure 3. Anonymous, Daniel Burckhardt-Wildt Apocalypse miniatures, ca. 1290–99. Fol. 40v, lot 60b, no. 2v, Cleveland Art Museum. Index of Christian Art, Princeton University.

Old temples had to die before new ones could be born; a myth persisted well into the Renaissance that the Temple of Peace in Rome was shattered the night Christ was born because a prophecy said that it would stand until a virgin gave birth.40 To illustrate the inexorable arc of Christianity, Renaissance painters made the once pastoral manger into a rich, multilayered site announcing the fate of paganism as well as celebrating the architectonics of the Church as a vessel of Christ within universal history. Renaissance painters turned the graves of antiquity and Judaism into the birthplace of their redeemer.

Figure 4. Duccio di Buoninsegna, Maestà, Nativity panel, ca. 1308–11. Tempura, altarpiece in Siena. Wikimedia Commons.

Allegorically the juxtaposition of the rude manger against the proud classical structures is significant for the emergence of the Renaissance because the death and resurrection of Christ is conflated with the period’s own conception of the death and resurrection of classical culture. The appearance of the ruin in these paintings therefore suggests the conflation of two historical propositions: first, classical culture was surpassed at the moment of Christ’s birth; second, classical culture had subsequently been dead up to the point of the Renaissance. By conjuring the ruin, the Renaissance delivered, in a single stroke, a fantasy of antiquity’s death and its resurrection.

By inventing the ruin, the Renaissance also invented itself as a self-conscious age. Broadly speaking, the Middle Ages did not see the ruin as a ruin but only as a remnant of a lost civilization or a foreign symbol. As Erwin Panofsky argues, scholars in the Middle Ages did not envisage classical antiquity as wholly different from their own time; therefore it was not necessary to preserve or venerate its material remains. In Panofsky’s eloquent formulation, “the Middle Ages had left antiquity unburied and alternately galvanized and exorcised its corpse. The Renaissance stood weeping at its grave and tried to resurrect its soul.”41 More recently scholars have complicated the art historian’s grand distinction between the medieval and Renaissance intellectual worldviews; for instance, Silvia Ferretti argues that Panofsky’s notion of the Renaissance artwork was temporally “antinomic,” occupying two incompatible schemata simultaneously.42 On the one hand, the artwork was fixed within a historical and immanent time; on the other, it inhabited an ideal and transtemporal order constructed by the artistic imagination. Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood have studied how both medieval and Renaissance works of art situate themselves in a dense network of temporalities, pointing backward to a remote ancestral origin, sideways to other replicas and citations, and forward toward a promise of its future remembrance.43 In short, all works of art exist as ruins in potentia.

Old and New

It is with the rebuilding of Rome in the mid-fifteenth century that ruins finally came to be imbued with a pervasive energy. After the return of the papacy for good in 1443, the efflorescence of culture and economy in Rome is inextricable from the changing perception and new appreciation of ruins.44 The ruins of Rome became the discursive signs and the raw materials of a true renovatio, constitutive of the very self-definition of the Renaissance. There arose a dense network of industries around the fallen monuments. In a collective effort to reassemble the past, popes, cardinals, architects, craftsmen, engineers, merchants, antiquarians, printers, numismatists, philologists, and poets all collaborated in the preservation, lamentation, and celebration of ruins.

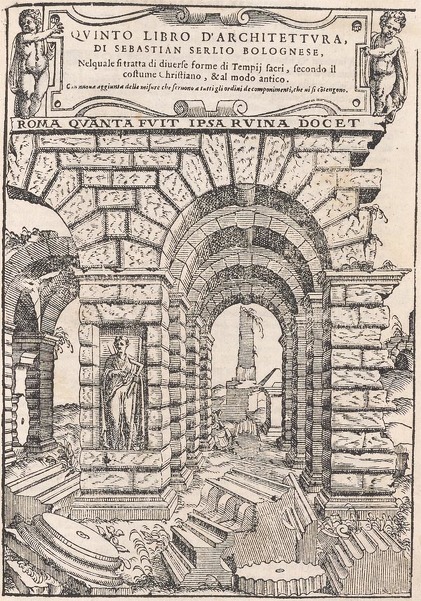

When the humanists saw ruins, what did they see? What did they want to see? The lapidary phrase Roma quanta fuit, ipsa ruina docet, “How Rome was, her ruins themselves teach,” epitomizes their didactic value.45 First recorded in Francesco Albertini’s 1510 Opusculum de mirabilibus novae et veteris urbis romae and made prominent in the frontispiece of the third book of Sebastiano Serlio’s 1537 Tutte l’opere d’architettura, et prospetiva, every word of this epigram carries weight (fig. 5). The contrasting tenses of fuit and docet underscore continuity and rupture between time past and time present. Quanta is about the magnitude, the distance between now and then. The pronoun ipsa as the intensifier stresses the evidentiary power of the ruin and the coextension between Rome as a totality and its materiality. In medieval thought the ruin has the power to teach (docere), but only as a moral lesson on the vanity of all things. For the early humanists the ruin teaches because it has real empirical value. It demonstrates the achievements of a past age and embodies recoverable knowledge.

The leading humanists strove to make rational order out of the ruin’s irrationality. In 1481 Leonardo writes to the Works Department of the Milan Duomo, hoping to get a commission: “I shall show what is the first law of weight and what and how many are the causes that bring ruin to buildings and what is the condition of their stability and permanence.”46 Almost every notable architect at some point used Rome as a classroom to study its lessons. Baldassare Peruzzi, Leon Battista Alberti, Sebastiano Serlio, and Andrea Palladio measured the broken remains of buildings and scrutinized the text of Vitruvius to deduce an ideal form all’antico.47

Others were not content with only recovering the epistemology of the material. They desired to use the ruin as a foundation to restore the totality of Rome. The titles of Flavio Biondo’s works are telling—De Roma instaurata (1444–48), Italia illustrata (1448, 1458, 1474), De Roma triumphante (1479)—for they trace the arc of his ambition, an enterprise to uncover Rome’s hidden physical, political, mythological, and architectonic structures so that they might become the foundations of nothing less than a complete restoration of ancient Rome. His contemporary, the antiquarian Cyriac of Ancona (1391–1453 or 1455), undertook adventures across southern Italy, Dalmatia, Egypt, Chios, Rhodes, Anatolia, and Constantinople, recording ruins and inscriptions in his Commentarii.48 In 1551 Leonardo Bufalini produced an extraordinary map of the Eternal City. Spanning six feet by six feet, it was “a horizontal ground plan based on survey[s] and made to scale—the first orthogonal representation of Rome since antiquity.”49 Pirro Ligorio, a man of immense energy, produced an enormous set of collated maps called Antiquae urbis imago (1561), showing the Rome that was. His goal, as he himself described it, was to “revive and conserve the memory of ancient things and satisfy those who take pleasure in them.” Accordingly this led him “to study, with enormous effort, every place and portion” of ancient remains, “not leaving a bit of wall, however small it was, without seeing it and examining it minutely: always accompanying this with the reading of . . . authors and . . . often having recourse to conjectures where the ruins were lacking.”50

Figure 5. Sebastiano Serlio, frontispiece of book 3 of Tutte l’opere d’architettura. Lyon, 1537. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Dozens of treatises on and view books, sketches, and prints of Rome were issued in the years following Albertini’s Opusculum (1510).51 Made mostly by foreigners, such as Antoine Lafréry, Étienne du Pérac, Hieronymus Cock, and Maarten van Heemskerck, these illustrations juxtapose the ruin as it is with the shining monument that it was imagined to be.52 In their voluminous virtuosity all these works transfer the material remains of the past to the textual record of the present. By doing so they become double monuments: the ruins testify to the achievements of antiquity, and, in preserving them, the modern documents are themselves impressive monuments of cultural productions.

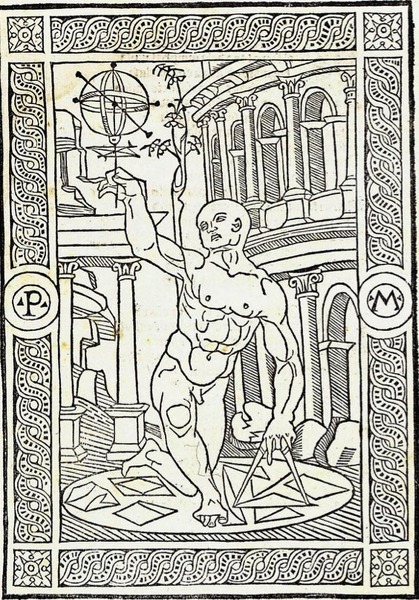

As representative of the newfound power of the humanist, consider the frontispiece of the anonymous Antiquarie prospettiche romane (ca. 1499–1500), a short humorous poem about the ruins and rediscovered statues of Rome (fig. 6).53 The image anticipates William Blake’s depiction of Newton: a muscular nude man kneels in the center, enclosed in a circle, drawing geometric figures on the ground with a compass in one hand while holding aloft an astronomical sphere in the other. In the background the Colosseum and some generic ruins split the frame. There is a clear parallel between the nudity of the man and the ruins, since ruins are in fact “naked” architecture—the human body and buildings reduced to their purest, unadorned state. His chiseled anatomy mirrors the lineaments of the crumbling monuments. Geometry and ruins hover between the concrete and the abstract, the mathematical and the material. In the erudite domain of the humanist, the study of the ruin is made into a branch of the lofty Vitruvian liberal arts, since to decipher its foundations one must know history, geometry, mechanics, and physiognomy.

Figure 6. Authorship uncertain, frontispiece of the Antiquarie prospettiche Romane, ca. 1499–1500. British Library.

Building by Destroying

Many of the central events in the Roman Renaissance involved ruins: the almost daily unearthing of statues, the rebuilding of St. Peter’s, the discovery of Domus Aurea around 1480, the Sack of Rome in 1527, and the discovery of the catacombs in 1578. As Leonard Barkan remarks, “The glories of new Rome were built on the ruination of old Rome.”54 Yet the exuberant rebirth of Rome came at a price: there was almost no edifice in Rome from the fifteenth century whose erection or renovation did not simultaneously cause the mutilation of some ancient structure. Conservation and destruction existed side by side. Though the enormously erudite Pope Nicholas V (r. 1447–55) founded the Vatican library, reinforced the city’s fortifications, cleaned and paved the main streets, and restored the water supply, he also permitted his architects to strip marbles from abandoned churches in order to adorn the cosmatesque pavement of St. John the Lateran and to despoil other churches and palaces.55 Sixtus IV (r. 1471–84), who reconstructed nearly forty churches and founded seven new ones, launched the symbolic program of the Capitoline Hill with a gift of recently unearthed statues, and built the first modern bridge over the Tiber, also used the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, and the temple of Venus and Jupiter as giant quarries.56 One contractor, Giovanni Paglia Lombardo, reportedly removed 2,522 cartloads of travertine from the Colosseum in a period of nine months.57

There were a few official attempts at preservation. Before he became Pope Pius II in 1457, Aeneas Piccolomini wrote admiringly of Nicholas V’s constructions, which rivaled those of the Roman emperors, he “deplored their immense unfinished masses which only added more ruins to the scene.”58 In his Commentaries he writes touchingly on the nostalgic sentiments that the ruins of Ostia, the Alban hills, and Hadrian’s villa evoked in him.59 Here is one of his verses:

Oblectat me, Roma, tuas spectare ruinas

Ex cuius lapsu Gloria prisca patet.

Sed tuus hic populus, muris defossa vetustis

Calcis in obsequium, Marmora dura coquit.

Impia ter centum si sic gens egerit annos,

Nullum hic indicium nobilitatis erit.60

It delights me, Rome, to gaze upon your ruins: from your fall the glory of the old is displayed. But now your people dig out the hard marble from the ancient walls and bake it in the service of lime. If this impious race continues thus another three hundred years, no vestiges of nobility will remain.

As pope he turned poetry into public policy by issuing a bull in 1462 proclaiming the prohibition of the destruction of architectural patrimony:

Since we desire that our Mother city remain in its dignity and splendor, we need to show all vigilant care that the basilicas and churches of the city and its holy and sacred places, in which are kept many relics of the saints, be maintained and preserved in their splendid buildings, but also that the antique and early buildings and their relics remain for future generations. . . . Thus, under pain of excommunication and of financial penalties expressed in this statute, which those who contravene it may incur forthwith, by our aforesaid authority and capacity we formally forbid all and singular, ecclesiastical as well as secular, of whatever eminence, dignity, rank, order or condition, even if of Pontifical eminence or of any other ecclesiastical or worldly dignity, to dare to demolish, destroy, reduce, break down or use as if a quarry, by any means, directly or indirectly, publicly or secretly, any ancient public building or the remains of any public building above ground in the said City or its district.61

Edicts of such sort had been periodically promulgated, but they had been only half observed and most of the time were ignored by the papacy itself for reasons of expediency and eminent domain.62

Indeed fifty years later Raphael and Castiglione in their 1515 letter to Leo X continue to lament that Roman palaces and churches were less harmed by the “Goths, Vandals and other perfidious enemies” than by those who mined their foundations for mortar and limestone. They urged the Papal See to establish a more robust program of civic preservation:

This is something that gives me simultaneously enormous pleasure—from the intellectual appreciation of such an excellent matter—and extreme pain—at the sight of what you could call the corpse of this great, noble city, once queen of the world, so cruelly butchered. . . . Thus those celebrated buildings that would today have been in the full flower of their beauty were burnt and destroyed by the evil wrath and pitiless violence of criminal men—or should I say beasts—although the destruction is not entire, for the framework survives almost intact, but without the ornaments; you could almost describe this as the bones of a body without the flesh.63

Conscious of the fact that the beautiful structures and ornaments of churches and palaces are built from the recycled mortar of ancient marbles, Raphael and Castiglione go on to inveigh against the popes who allowed these antiquities to fall prey to ruin and spoliation. David Karmon has recently offered a major correction to the accepted view that the worst devastation of the Roman Forum occurred during the fifteenth to sixteenth century, arguing that Renaissance popes did indeed develop a comprehensive program of conservation and preservation.64 Still it is undeniable that the leading humanists used strong polemics against the city’s systematic plunder.

When Castiglione does reflect on the surviving ruins of Rome, however, it is only to lament the work of that ultimate destroyer, Time:

Superbi colli, e voi sacre ruine,

Che ‘l nome sol di Roma anchor tenete,

Ahi che reliquie miserande avete

Di tante anime, eccelse e pellegrine!

Colossi, archi, theatri, opre divine

Triomfal pompe gloriose e liete,

In poco cener pur converse siete

E fatte al vulgo vil favola al fine.

Cosi se ben un tempo al tempo guerra

Fanno l’opre famose, a passo lento

E l’opre e i nomi il tempo invido atterra.

Vivrò dunque fra’ miei martir contento,

Che se’l tempo da fine a ciò ch’è in terra,

Darà forsi anchor fine al mio tormento.65

Proud hills and you sacred ruins

Who only keep the name of Rome

Ah, what miserable relics you hold

Of so many exalted, extraordinary souls!

Colossi, arches, theaters, divine works,

Triumphal pomp, glorious and happy,

You have turned into a bit of ash

And finally become a cheap fable for the vulgar.

Thus, if for a time the famous works

Make war on time, slow-paced time

Enviously brings down both works and names.

So I shall live happily among my martyrs:

For if time brings an end to what is one earth,

It may yet bring an end to my torment.

Francesco Orlando, in his magisterial Obsolete Objects in the Literary Imagination, writes that this Petrarchan sonnet is a prime example of the category of the “solemn-admonitory . . . a lesson in human transience, proffered, however, by a profane historical event, with the impressiveness of its unrestorable remains.”66 In a lofty, brooding tone, the author of Il Cortigiano enumerates many of the well-rehearsed topoi surrounding Roman ruins: the pleading vocatives to the overwhelming monuments, the disparity between the name of Rome and its immaterial substance (something Du Bellay will reiterate), the battle between a temporality that corrodes and an artifice that endures, the yawning disparities between spiritual permanence and architectural transience. After the catalogue of direct addresses—voi, tenete, avete, sete—the energy of the first three quatrains converges on the emphatic vivrò of the last, “I shall live,” as if taunting the fallen monuments. The author hopes that temporal equity will bring moral restitution (se’l tempo da fine . . . Darà forsi anchor fine); if all things end, his torments too shall be extinguished by time.67

A visual counterpart to Castiglione’s poem might be Herman Posthumus’s Landscape with Ancient Ruins (1536), which illustrates the antiquarian fantasy of accumulation (Plate 6).68 The imaginary landscape seems both haphazard and artfully arranged: the shattered artworks—busts, tombs, reclining figures, columbaria, arches, columns, friezes—demonstrate how much of antiquity has been lost, yet their copious quantity suggests that much remains. Amid such abundance a diminutive figure measures a gigantic broken base inscribed with a passage from the Metamorphoses: TEMPVS EDAX RERVM TVQVE INVIDIOSA VESTVSTAS O[MN]IA DESTRVITIS, “Oh, most voracious Time, and you, envious Age, you destroy everything” (15.234–36). Yet surely not everything is gone, for by filling his canvas with an excess of surviving treasures, the painter ironically defies such Ovidian despair. An obvious way of reading the painting’s message is that it is about the melancholy of lost time. Another way can be instead a translatio imperii; the victor surveys the open-air market filled with spoils from the vanquished that are ready to adorn a discerning patron’s palace.

The notion of architectural fragments as leftovers is explored in the episode of Astolfo’s voyage to the moon in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (1516–32). On a quest to retrieve the lost wits of Orlando, Astolfo is given instruction to ascend to the silvery orb of night, where all things that are lost on earth can be retrieved. This lunarscape is, one might say, the ultimate antiruin. By following an imaginative interplanetary law of conservation, the moon serves as an excellent permanent storage facility for all things, halting their disintegration on a scale unavailable even to the most resourceful antiquarian. Yet it is just a cosmic garbage dump. Parodying the connoisseur’s excesses, Ariosto fills the moon with random things—swollen bladders, golden and silver fish hooks, talons:

Ruine di cittadi e di castella

stavan con gran tesor quivi sozzopra.

Domanda, e sa che son trattati, e quella

congiura che sì mal par che si cuopra.

Vide serpi con faccia di donzella,

di monetieri e di ladroni l’opra:

poi vide bocce rotte di più sorti,

ch’era il servir de le misere corti. (34.79)

Ruins of cities and of fortresses

Lay scattered all about, with precious stores,

Plots ill-contrived, broken alliances,

Feuds and vendettas and abortive wars,

Serpents whose faces had the semblances

Of thieves and coiners and seductive whores.

Phials lay broken—he saw many sorts—

The futile service of ungrateful courts.69

As David Quint has argued, this episode of the moon reverses the Dantean principle of allegory according to which the scattered signs on earth serve as vectors of divine things above.70 In Ariosto’s fiction the ascent yields only a messier version of Posthumus’s Roman ruins. By refusing to weave the bric-a-brac of the quotidian into a providential order, Ariosto signals the collapse of epic teleology.

Finished Architecture

Ruins, of course, need not be seen as tragic reminders of the past; they are a natural part of the life cycle of a building, in which the building exists in the intention of its creator, comes into material being at a specific site, matures, and eventually disappears. In Buildings Must Die Stephen Cairns and Jane M. Jacobs argue that architectural theory and practice must be aware of a building’s juvenescence and senescence.71 We usually think of time as blemishing the integrity of a work, but as Mohsen Mostafavi and David Leatherbarrow remark in On Weathering, staining and erosion actually contribute to a building’s identity, since architecture is an accumulation of experienced history. “Finishing ends construction,” they write; “weathering constructs finishes.”72 Enmeshed in the very fabric of the city and social life itself, buildings are constantly altered not only by nature but also by their occupants, changing the architect’s noetic intention to accord with the inhabitants’ daily needs.

As such, there is never an ideal state of perfection in a building, no such thing as an un-ruin. Indeed all constructions in premodern Europe took place in the longue durée, taking multiple decades, generations, or even centuries. Marvin Trachtenberg characterizes the “premodern regime of architecture” as having “a slow velocity of the time of the building; a high inertial endurance of the resulting structure and a relatively high speed of the life-world.”73 The great, unfinished projects of the medieval cathedrals of Siena, Bologna, and Florence exist as beautiful counterpoints to the Roman aesthetics of ruins, all residing in a palimpsestic locus of urban mutability.

For Trachtenberg, Leon Battista Alberti definitively changed the Romanesque and Gothic way of architectural construction by inventing what he calls the “Building-outside-Time” as a bulwark against ruinous contingency. Rejecting an earlier practice that integrated material duration into the identity of monumental architecture, Alberti sought to efface all temporal measures of mutability in order to establish a permanent, spatial representation of the ideal. The polymath writes in De re aedificatoria (1485), “I sometimes cannot stomach it when I see with what negligence, or to put it more crudely, by what avarice they allow the ruin of things that because of their great nobility the barbarians, the raging enemy have spared.”74 Alberti thus aspires to construct a classical building that would be a powerful agent against contemporary disorder, a material reflection of the virtuous magnificence of antiquity. Since a key Albertian principle is that “harmony is a perfection of the parts within a whole,” the slow, collective method of medieval architecture was now unacceptable because additions and renovations would always spoil the original intentions of the singular architect. Thus he aspired to create a building “out of time,” impervious to the forces of contamination.

Alberti’s preference for fixed abstraction over the messy fluidity of time is displayed in his Descriptio urbis romae (ca. 1444), the first Roman survey to record the quantitative coordinates of its boundary in respect to the relative distances of the monuments. According to Mario Carpo, the Descriptio transforms the topography of Rome into “a system of points designated only by polar coordinates, without any other form of graphical documentation.”75 Carpo argues that, instead of drawing actual monuments, Alberti invented the digital image, in the literal sense of images translated into a sequence of numbers, so that the decaying sites of Rome abstract themselves into mathematical coordinates. The spirit of Albertian mathematics thus arises to annihilate once and for all the ghosts of classical ruins by reducing their corpses to pure numbers.

The contrast between the fixed, singular monument and the slowly accrued, multigenerational monument is important to my thinking about the temporality of the work of art. Renaissance artists—whether they used things or words—hoped that their work would transcend its temporal and spatial horizons; at the same time they knew their work lived in the material world, where it faced the possibility of being recycled, spoliated, cited, and transformed by its successors. These two axes—one timeless, the other temporal—drive much of the discourse surrounding ruins.

Mechanical Reproduction: Doubles

In the Renaissance construction looks like ruins and ruins look like constructions. The popes envisioned St. Peter’s as the earthly representation of the Kingdom of God. Yet the rebuilding of the great basilica was a controversy from the time of Nicholas V, spanned no fewer than eighteen popes and twelve architects, and for over a century resembled an enormous construction site in disrepair.76 Donato Bramante (1444–1514), the primary architect under Julius II, was dubbed “Il Ruinante” because of the massive destruction he caused.77 In order to realize his unprecedented plans, Bramante ordered the demolition of the area behind the apse and the removal of the Probus mausoleum as well as large parts of the transept and the western half of the nave.78 At multiple points construction came to a halt; a temporary roof covered the basilica’s half-finished walls for decades. Vasari’s Paul III Farnese Directing the Continuance of St. Peter’s in the Palazzo della Cancelleria (1544, fig. 7) shows the disorganized state of affairs: the patrons, planners, and workers all teem about confusedly. In the background it is difficult to tell whether the marble half-rotunda in front of the old Constantine basilica is rising or falling.

According to Christof Thoenes, for the draughtsman no basic difference exists between new construction and an antique ruin.79 The Netherlandish artist Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574) drew St. Peter’s from multiple perspectives, capturing the ambivalence of its building process and the porosity between exterior and interior space (figs. 8 and 9). One shows the interior from the east with Bramante’s tegurio. In 1513 Bramante built an improvised shelter on the tomb of Peter and the altar above it. The small Doric arcaded structure was intended to preserve the sacred site’s identity, serving as a transition between the destruction of the old building and the construction of the new. Its style was classical, but it was made of poor peperino stone and was meant to serve only as a temporary facility. Interestingly, Nagel and Wood point out that Vitruvius uses the word tugurium for the primitive huts that are the origins of architecture. In their reading, Heemskerck’s reinvented tegurio pays homage to its humble architectural ancestors and gestures toward its sacred origins, as a memory of the tabernacle in the desert and the hut-as-manger motif in the Nativity paintings.80

Figure 7. Giorgio Vasari, Paul III Farnese Directing the Continuance of St Peter’s, 1546. Fresco, Palazzo della Cancellaria, Rome. Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Susan Stewart insightfully observes that the activity of printmaking shares a close kinship with ruination, since it works by the process of erasure.81 The printmaker’s instruments (etching needles, burins, and rollers) and printmaking’s chemical processes (using acids, water, and ink) literally ruin the plate by “biting” it. Thus the production of the image depends on the destruction of its original incision. Indeed the technical execution and its subject of ruins converse in an appropriate dialectic: the effects of weather and water stains, the geological strata intruding on the urban landscape, and the profusion of greenery twined over decrepit buildings are all represented on the surface of the paper made from wood pulp. Yet the very act of depicting them encloses them as artifacts, thus calling attention to their fragile conditions as well as remonumentalizing them as precious objects to behold and preserve through the medium of print.

The surplus of ruins in Rome is mirrored by the very multiplicity of its representations. These range from pocket travel guides, scrapbooks, postcard albums, miscellanies, and architectural treatises to huge antiquarian folios. Blaise de Vigenère in 1579 lambasted the printers who, “in order to make up a book quickly, snatch, borrow, and steal wholesale and haphazardly from ancient authors, just as in the exploitation of the Colosseum, the Antonine baths and of other exquisite buildings in Rome, others have barbarously hastened their decline by making out of them small figures, wretched huts and other appendages.”82 Antoine Lafréry’s Speculum romanae magnificentiae (ca. 1540), reprinted multiple times, is a case in point: assembled from his three-decade-long career as a printer in Rome, the largest collection contains some 994 engraved maps, portraits, and subjects historical, biblical, and mythological.83 Tourists and other collectors would make their own selections and have them bound to their own tastes. If travertine was salvaged for church foundations, why couldn’t prints be reframed for new purposes? Broadly disseminated, reused, copied, prints reflected the bricolage nature of their subject.84

One of the most impressive—and enigmatic—prints of ruins is a collaboration between Bramante and Bernardo Prevedari. As the largest surviving fifteenth-century engraving made from a single plate, Ruined Temple (1481, 28 x 20 inches) presents a scene split between the interior of a highly ornamented church and an exposed side falling into disrepair (fig. 10). Many details are obscure: in the foreground the kneeling monk’s shadow is reduced to a skinny triangle, with its apex pointing to the decorated column; a gigantic candlestick conceals a pagan idol with a minuscule cross atop; friezes on the cupola show an ox-drawn cult procession bearing a small statue of Cupid; centaurs cavorting and nude men wrestling line the wall of the apse; the circular opening above the apse shows the back of a bust; hairline cracks run across the stone pavement; shattered debris lingers. With meticulous incised lines and stippling, Bramante creates the illusion of depth, shadow, and mystery. The image gives the aesthetic effect of estrangement and misrecognition: Is it a converted pagan temple? Is the man lapsing into idolatry? Is old religion really defunct? Whereas much of Renaissance design labored to transfigure the space of the church into a capacious vessel in which the incompatible and the anachronistic were subsumed into a sweeping architectonic whole and theological unity, Bramante’s composition seems to revel in its ambivalence and heterogeneity.85

Figure 8. Maarten van Heemskerck, pillar of the crossing of new St. Peter’s Basilica, 1532–36. Pen and brown ink. From Römischen Skizzenbücher I, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Art Resource, New York.

Palimpsest and Paper

“Palimpsest” is the commonplace that describes the ever-changing Rome as an overdetermined site in the classical tradition. It is worthwhile to point out that the palimpsest is, above all, an invention of the Middle Ages. As the former skin of an animal—the protective layer that surrounds its body—it is repurposed for human use as the medium for the preservation of memory. The script on a page, like scars on a beast, marks the record of the creaturely experience. The parchment’s unique feature, of course, is its ability to be erased, to be reinscribed by different hands; all the while its traces are buried on the surface, visible upon close inspection. Thus the palimpsest is a good metaphor and metonym to describe what is at stake in the medieval relationship between words, objects, and Rome: a pagan past upon which Christianity was inscribed. Though there is much erasure, much remains.

Figure 9. Maarten van Heemskerck, interior view of the nave of old St. Peter’s Basilica, ca. 1532–36. Pen and brown ink, wash. From Römischen Skizzenbücher II, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Art Resource, New York.

As palimpsest is to the Middle Ages, so paper is to the Renaissance. Parchment bears the qualities of the medieval era: it is singular, unique, and laborious. Mechanical print, however, is replicable, cheap, and prodigious. Above all, it meant a wide diffusion. It is no accident that some of the most popular incunabula were Petrarchan poetry and guidebooks to Roman ruins. With their various copies, editions, and sizes, poetic collections and illustrations of ruin proliferated thanks to the agent of mechanical reproduction. This is the material condition in which the Renaissance poetics and pictorials of ruins were able to survive, expand, and flourish.

Figure 10. Donato Bramante and Bernardo Prevedari, Ruined Temple, 1481. Engraving. The Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource, New York.

With the advent of mechanical reproduction, historical monuments have secondary lives as mediated images. They survive and multiply in cultural memory by means of readily available, reproducible images, whether visual or verbal. For the foreigner the power of Roman ruins resides in their distance—the gap between source and destination—and their images come to stand in for the “original.” In other words, the aura of the monument lies in its remoteness, its inaccessibility, its inhabitation of another time and land. The image, on the other hand, lives in its “here-ness”—something to be grasped with one’s hands in the comfort of one’s home, tangible and portable. Sooner or later the very proliferation of the ruin’s representations (including literary ones) may well supplant the yearning to recover an image’s origin, so that we eventually prefer the image to the imagined, nonexistent original, whether it be the ruined Colosseum that still exists today or the perfect one in the time of Vespasian. In the famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility” (1936), Walter Benjamin claims that reproduction not only contributed to originality; it preceded it: an art object became authentic only in its afterlife, not at the moment of its inception.86 In his autobiography Goethe confesses that when he saw Rome for the first time late in life, he was disappointed, because his childhood imagination was conditioned by his father’s prints of Piranesi, which were more impressive than the actual sites.87 In antiquity’s absence the white arena of the printed paper becomes the new space of the imagination.

As a dismembered body stubbornly fixed to its geographical habitus, the ruin lost its use-value long ago, yet it assumes a new monument-function as a sign of its former glory; all the while its specter is ubiquitous, haunting the cultural imagination far and wide. In the massive, encyclopedic wreckage that is Benjamin’s Arcades Project (1927–40), one slip in his Konvolut J records:

It’s not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation. In other words, image is dialectics at a standstill. For while the relation of the present to the past is a purely temporal, continuous one, the relation of what-has-been to the now is dialectical: is not progression but image, suddenly emergent.—Only dialectical images are genuine images (that is, not archaic); and the place where one encounters them is language. [] Awakening. []88

In this sense a dialectic image is the ruin and its representation doubled: the flash of past and present as well as the flash between the original and its representation. As I have noted, the ruin refers back to a monument that might not even have been finished. It is not a representation, but it is not the thing itself either. This is the first derivative: a lapsed identity. The second: the drawing of a ruin poses another paradox, existing as a mimesis of a mimesis, a copy of a shadow. Third, the engraved plate of a drawing, as Stewart argues, is a ruin. Fourth, in the age of mechanical technology, the engraving reproduces multiple copies that occupy multiple spaces simultaneously. Thus the representation of the ruin moves between singular and multiple ontologies, coexisting in overlapping temporalities, projecting lines of futurity beyond itself, much like the Shakespearean promise of literary repetition in “states unborn and accents yet unknown.”

Babel Visualized

Recall how chapter 1 began with the dual etiologies of the births of linguistic fragmentation and ars memoriae, one from scripture and the other from classical rhetoric. We see these two discourses coalesce in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1563 Tower of Babel (plate 7). In one image the Dutch artist conflates the allegory of human pride in the Bible with the largest amphitheater of ancient Rome. There are numerous ironies: the construction of the Colosseum begun under Vespasian is funded by the spoils from the Second Temple in Jerusalem; Northern Reformation polemic often referred to Rome as the Whore of Babylon, but the town at the base of the Tower resembles Bruegel’s native Antwerp. In the foreground, where heaps of chiseled stone lie, masons genuflect before Nimrod and his retinue, thus reversing the biblical material of construction (“And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar”; Genesis 11:3). The bottom half represents either a geological crag from which the tower is being quarried, or the collapsed edifice itself. The top half, resembling a gigantic wound, exposes the inside of the Tower, which duplicates its outer shape. A closer look reveals a significant detail: its rings are not parallel to the ground; rather the form is in the shape of a spiral. The cyclical form is replicated in diminishing proportion from top to bottom. The mirroring of the inside to the outside induces feelings of both harmony and confusion, as if the dizzying structural sameness is reflective of the builders’ ingenuity, as if in the labyrinthine levels man was so confident of his cleverness that he began to dupe himself. The confusion of logos—coherent architectonic system—seems to both defy and explain the structure.

There were many depictions of the Tower of Babel in the early modern period. Bruegel and his son painted at least three.89 It is no surprise that the Tower of Babel, whose very story is about linguistic dispersal and failed architecture, would find so many pictorial representations in this era, for the story marks the mythic origins of cultural differences, the folly of human enterprise, and the ruinous foundations of all art—all problems with which Renaissance thinkers were preoccupied. Thus Bruegel’s painting serves as a fitting final image for this chapter, the purpose of which was to demonstrate that the identity of the Eternal City underwent innumerable metamorphoses through her architectural renovations and innovations. The representations of the Eternal City likewise underwent myriad shifts in texts and images and moved from the singularity of the medieval palimpsest to the multiplicity of the early modern print. As a building’s constituent parts—pediments, cornices, shafts and bases of columns—were ripped from its original site and transported across the city and beyond, guidebooks, prints, récits de voyage, mirabilia, and other memorabilia carried Roman images far and wide. Poetry, then, offers a verbal response to such diverse assemblages. In the chapters that follow, we shall see how Petrarch, Colonna, Du Bellay, and Spenser, each in his own way, wrested poetic order from the chaos of material and linguistic ruins.