Chapter 6

Spenser’s Moniment and the Allegory of Ruins

Allegories are, in the realm of thoughts, what ruins are in the realm of things.

—Walter Benjamin

The earliest surviving definition of monumentum comes from the first-century Latin lexicographer Varro’s De lingua latina:

Meminisse, “to remember,” comes from memoria, “memory” since there is once again movement back to that which has stayed in the mind; this may have been derived from manere “to remain,” like manimoria. And this the Salii when they sing “O Mamurius Veturius” signify a memoria, “memory.” From the same word comes monere, “remind,” because he who reminds is just like memory; so are derived monimenta, “memorials,” which are in burial places and for that reason are situated along the road, so that they can remind those who are passing by that they themselves existed and that the passersby are mortal. From this use other things that are written or produced for the sake of memory are called monimenta, “reminders.” (6.4)1

Varro’s gloss of the monument underscores the affinity between places and memory, remembrance and projection, tombs and writing. Roman necropoli were located on the exit roads of cities, separating the residences of the living and the cultic sites of burial.2 The Via Appia, punctuated by reminders of death, not only measures the distance traversed from one geographical point to another but also maps the larger itinerary of life, acting as a hinge in which the past and future are in the hic et nunc. Proleptic and analeptic, a tombstone interrupts the quotidian activity of walking, seizes the pedestrian’s imagination, and pitches his thoughts toward mortality.

Spenser’s career, punctuated in an analogous way by the word moniment, measures the distance his writings have traversed and maps a larger itinerary of his poetic project, which engages in a fundamental rethinking of the activities of monument making and its dialectical other, ruination. In his poems monuments and ruins function as allegorical signifiers that shape both the content and the form of his work.

Within the moral topography of Spenser’s world a ruin is usually a false monument, a sign of our postlapsarian state. The destruction of Roman temples in A Theatre for Voluptuous Worldings (1569) or The Ruines of Rome (1591) is a sort of righteous disenchantment. In the attempt to turn a ruin back into a monument, idolatry threatens to reemerge, as in The Ruines of Time (1591). Monuments in The Faerie Queene (1590, 1596) are supposed to instruct, yet more often than not they are on the verge of catastrophe. For Spenser true, lasting monuments—whether Britons monuments in Book II or the text of The Faerie Queene writ large—are those that spur the mind to action. A true monument, more than a thing to be passively gazed at, must be decoded, interpreted, and interrogated.

An earlier generation of Spenserians—Northrop Frye, Harry Berger Jr., Angus Fletcher, James Nohrnberg, Judith H. Anderson, and more recently Kenneth Gross and Gordon Teskey—are particularly attuned to the English poet’s allegorical imagination and engagement with the mythopoeic strains of the classical tradition. A younger generation—Andrew Escobedo, Andrew Hadfield, Willy Maley, Rebeca Helfer—are more concerned with the local textures, historical complexities, and struggles of national formation in the 1590s. They read monuments and ruins as the aftermath of Reformation iconoclasm and the dissolution of the monasteries. My critical position pivots between these two spheres in order to argue that Spenserian ruins are both a rupture caused by a failure of the allegorical imagination to yoke together the ideal and the apparent, and a material instantiation of the iconoclastic upheavals of late sixteenth-century England.

Because allegory in essence traffics between two worlds—the earthly and the eternal—it is a particularly apt method to understand the dialectic between the monument and the ruin. This dialectic turns out to be symptomatic of a host of other important frictions in Spenser’s work: paganism and Christianity, concealment and revelation, iconoclasm and idolatry, degeneration and consummation, fragments and totality, accidents and teleology. These tensions—highly unstable, always on the brink of chaos—constitute the very structure of meaning in his poetry. Allegory as a means of subsuming all these elements is therefore put under enormous pressure. Thus a Spenserian poetics is always in danger of fragmentation. His poetic monuments, then, are as much about the allegory of ruins as the ruins of allegory. That is to say, ruins are allegorized, but allegory itself is ruined in this antagonistic struggle between poetic making and interpretative disorder.

In the previous chapters I examined authors who tenuously traced the shadows of the past through the melancholic science of a philological poetics (Petrarch), oneiric inventions of architectural follies (Colonna), and a nationalist zeal for creative destruction (Du Bellay). Here we have an English poet whose imagination is invested in allegory in its most intense form. If vestigium (the trace) is form without matter, and cendre (ash) pure matter without form, then moniment is supposed to be the coalescence of form and matter into a well-wrought artifact of allegory. We shall see how fragile this artifact is.

Ruinous Beginnings

The Italian Renaissance, as we have seen, drew its inspiration from the mighty obsolescence of ancient Rome. The landscape of England, however, was dotted with not only Roman remains—the diffusion of roads, walls, fortifications, and baths throughout the region—but also the faint traces of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman cultures. To this palimpsestic landscape the sixteenth century added many more ruined sites, wrought by the Suppression Acts that dissolved churches, monasteries, and other religious property.3 The Royal Injunctions of 1559 stated that all “tables, candlesticks, trindles, and rolls of wax, pictures, paintings all monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry, and superstition” of Catholic institutionalization must be destroyed.4 Iconoclasm is the practice that cleanses such millennial accretion to reveal the true meanings of the faith. In the Protestant imagination a true monument is supposed to transmit spiritual radiance to the world of earthly decay. As James Simpson observes, “The official programmes of iconoclasm between 1536 and 1550 seek to distance the past from the present as rapidly and decisively as possible either by demolishing the medieval, or more enduringly perhaps, by creating the very concept of the medieval as a site of ruin.”5

The English countryside was indeed filled with Shakespeare’s “bare ruined choirs where late the sweet birds sang” (Sonnet 73). Yet as Alexandra Walsham has explored in her important The Reformation of the Landscape, iconoclasm was prolonged and contentious, not the definitive eradication of sacred sites that earlier scholars had claimed.6 Landscapes still retained traces of the sacred. Popular belief considered wells, trees, stones, rivers, wayside crosses, and ecclesiastical buildings to exude supernatural qualities. Shrines and places of pilgrimage continued to exert their centrifugal pull. Ruined abbeys, such as the chapels of Glastonbury and Cornwall, glowed with the aura of the numinous. The initial spasms of Henry VIII’s despoliation prompted a nostalgic desire to preserve the relics of the past—even if they were by the Druids, Saxons, Celts, or Danes.7

It is not surprising, then, that scenes of ruination occupy an ambivalent place in Spenser’s work: are the ruins to be mourned, or were they the victorious signs of divinely sanctioned punishment? His first publication, in 1569, at seventeen, was his translation of Jan Van Der Noot’s Theatre for Voluptuous Worldlings, containing visions of apocalyptic destructions; in the 1590 Faerie Queene there is the despoiling done by Kirkrapine in Book I, the violence wrought upon the Bower of Bliss in Book II, and the conflagration of Busyrane’s castle in Book III. The Complaints, published as a collection in 1591, begins with the Ruines of Time; at its center is a translation of Du Bellay’s Ruines of Rome; it concludes with Visions of the Worlds Vanitie, The Visions of Bellay, and The Visions of Petrarch, all of which are reworkings of the Theatre translation. There are countless moments of destruction in the 1596 Faerie Queene: Book V takes as its central theme the use of violence in pursuit of the good; and finally the entropic force of the Blatant Beast concludes Book VI. Throughout, the razing of buildings testifies to the self-defeating hubris of human ingenuity. Within the moral universe of Spenser’s poetry, an effort to create something physically permanent merely hastens the hour of doom.

Spenser’s personal life too was dominated by real forms of the ruin. After his employment as private secretary to Lord Grey of Wilton, the lord deputy of Ireland in 1580, the poet inhabited a series of appropriated Irish properties, including a dissolved monastery at New Ross until 1584. He also leased a house in Dublin and a ruined Franciscan monastery called New Abbey, near Kilcullen in the County Kildare. In 1586 he was assigned 3,028 acres in Cork, which included Kilcolman Castle, his principal residence until it was sacked by rebels in 1598.8 Thus as he was composing The Faerie Queene he was literally living in the shadow of Irish ruins.

These individual encounters with ruins were, of course, all part of a much larger project of ruination with which Spenser was actively involved. England’s colonialist enterprise in Ireland was a project that, like the dissolution itself, entailed the eradication of a culture that in Elizabethan terms was theologically pagan and politically barbarous. Spenser’s prose dialogue, A View of the Present State of Ireland (written in 1596, published posthumously in 1633), advocates for the English subjugation of Ireland. As scholars have noted, in light of the View’s radical policies Henry VIII’s abolishment of monasticism was but a prelude to a much more devastating solution to the Irish problem.9 His plan—to convert the country from the rule of oppressive, warring regional chieftains to the rule of the oppressive, warring, centralized English Crown—was to repair Ireland by ruining it.10

Even Spenser’s language can be considered a self-fashioned ruin. With his penchant for obscure puns and archaizing orthography, the famous strangeness of the Spenserian style bespeaks his larger project of reforming the English language by excavating its various dialects as well as Anglo-Saxon, continental, and classical roots.11 In his desire to lend prestige to his style, Spenser invents an archaic tongue that takes on a vintage patina. He rummages through the relics and remains of these antiquated lexicons, at times restoring them, at times distancing them. The unusual orthography of moniment reflects this: as a variant form of monumentum that more audibly evokes the root monēre, “to warn,” it resembles a self-fashioned dusty artifact. In other words, the signifying sense of the word is venerable and the word as a sign itself appears old.

In the epistle to The Shepheardes Calender (1579), E.K. declares:

I am of opinion, and eke the best learned are of the lyke, that those auncient solemne wordes are a great ornament both in the one and in the other; the one labouring to set forth in hys worke an eternall image of antiquitie, and the other carefully discoursing matters of gravitite and importaunce. For if my memory fayle not, Tullie in that booke, wherein he endevoureth to set forth the paterne of a perfect Oratour, sayth that ofttimes an auncient worde maketh the style seeme grave, and as it were reverend: no otherwise then we honour and reverence gray heares for a certein religious regard, which we have of old age. yet nether every where must old words be stuffed in, nor the commen Dialecte and maner of speaking so corrupted therby, that as in old buildings it seme disorderly and ruinous. But all as in most exquiste pictures they use to blaze and portraict not onely the daintie lineaments of beautye, but also rounde about it to shadow the rude thickets and craggy clifts, that by the baseness of such parts, more excellency may accrew to the principall; for oftimes we fynde ourselves, I knowe not how, singularly delighted with the shewe of such naturall rudenesse, and take great pleasure in that disorderly order. (15–16)12

Spenser here carefully spells out his theory of linguistic archaism. Invoking the authority of Cicero, he advocates for ornamenting a text with “naturall rudenesse” and “disorderly order” so that it imparts the prestige of seeming “grave” and “reverend.” This aesthetics of purposeful rustication is part of his greater program of the reformation of language. In recuperating old words, the author of The Faerie Queene recovers the sedimented layers of the antique and tries to civilize a rude tongue through rhetorical invention. As one critic has noted, “Just as the universe appeared to Spenser to have decayed visibly since antiquity, so words had decayed; and the consequent mismatch between words and things was an index of moral confusion. To retrieve the etymons would be to repair the original bond between words and things on which are predicated epistemological distinctions between truth and falsehood and moral distinctions between good and evil.”13 Traces of an earlier epoch and culture are underscored on the surface of his texts, and Spenserian language builds into itself as part of its alienating effect an index of conflicting temporalities. As such, there is a “double historicity” in Spenser’s unusual style: the poet’s self-exegesis and lexical choices are ways of staking his claim that he belongs to an earlier time and temperament as well as ways of signaling his oblique participation in current Elizabethan politics through the dissembling guise of allegory. His use of “moniments” and “ruines” is one way of constructing his aesthetics and ethics of decay.

“Grauen” Images

But before all that the young Spenser’s first publication was A Theatre for Voluptuous Worldings (1569), which partakes in the iconoclastic and apocalyptic energy of the Reformation. Lawrence Manley suggests that the true beginning of Spenser’s career “rests not in Arcadia, but in the urban ruins of antiquity.”14 Between his education at Merchant Taylor’s School in London and his entrance into Cambridge, Spenser published a translation from the French of Jan van der Noot’s Dutch Het theatre oft toon-neel.15 It comprises three blocks of texts: a translation of the visions of Petrarch after the death of Laura in Rerum vulgarium fragmenta 323, Du Bellay’s Songes, and four sonnets by van der Noot based on St. John’s visions in the Book of Revelation. A Theatre, reworked in the hands of Spenser, essentially contains in nuce his idea of monuments as moral warnings: all material artifacts are transitory; they must be supplanted by verbal ones that reveal their inconstant nature.

According to van der Noot, the purpose of A Theatre for Worldlings is “to settle the vanitie and inconstancie of worldly and transitorie thyngs, the liuelier before your eyes, I have broughte in here twentie sights or vysions, & caused them to be grauen, to the ended al men may see that with their eyes, which I go aboute to expresse by writing, to the delight and plesure of the eye and eares.”16 Notice the irony—whether intended or unintended—of “grauen.” Clearly it means “printed” here, but it is a small semantic step from the Mosaic prohibition of graven images or idols. For Calvin the nature of man is “a perpetual factory of idols” such that he “conceives an unreality and an empty appearance as God,” leading him to express this phantom in the manufacture of actual idols.17 A mid-sixteenth-century preacher warned his congregation, “Good friends, you must by science and cunning, learnedly speak of Images and Idols, and not to confound the words, or the things signified by them, taking one for another.”18 When images such as those depicted in A Theatre for Worldlings are valued too much, they turn into idols.

Whereas the exterminating agent of monuments in sixteenth-century England is the Reformer’s hand, in A Theatre for Worldlings it is the divine will, expressed through the force of natural calamity, that provides the destruction: wind, thunder, earthquake, and fire. The destroyed things in the poems—human constructions, such as a ship, a temple, an obelisk, and a triumphal arch, as well as things of the natural world, such as deer, a spring, a tree—are thus instantiations of the transience of all earthly things. Drawing from the fervor of Protestant millennial anticipations, apocalyptic destruction in Spenser’s verses goes hand in hand with the impulse of iconoclasm, for both operate under the guise of purification. Ruins in Worldlings constantly point to the temporal limits of material things. Hence the language they speak is that of the Apocalypse, an unveiling that cleanses the world of physical dross.19

Spenser thus turns the trope of the ruin from a humanist exercise of remembrance of things past into a Christian anticipation of time’s end. Indicative of the Reformation’s privileging of word over image, the movement generally preferred textual monuments—scriptural or poetic—to physical ones.20 Martin Luther’s translation of the Old Testament was called the Denkmal, German for “monument.” Similar to the etymology of monimenta, “to remind,” a Denkmal, with the root of denken, “to think,” is clearly meant to provoke reflection.21 Spenser’s textual practice also harks back to the operations of the mind: through the activity of reading, the materiality of the poet’s letters dissolves into the discursive space of his words. This operation is completed with the use of emblem poetry, in which an image is juxtaposed with explicatory verses. Careful exegesis disentangles true images from empty idols.

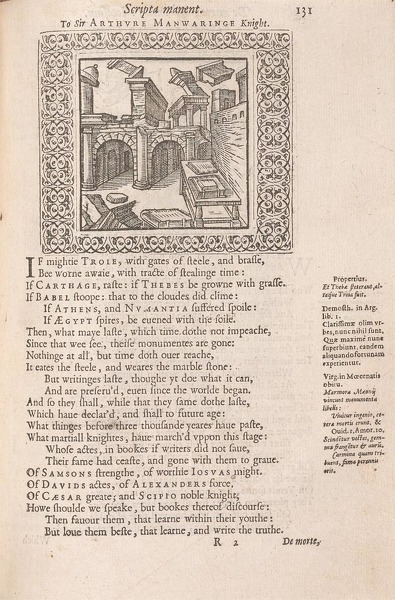

Figure 13. Edmund Spenser, Sonnet 3, Theatre for Worldings (London, 1591). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The best example of a false monument becoming a ruin is the illustration of the obelisk in the third sonnet (fig. 13). In Renaissance Europe there was a craze for all things Egyptian, especially obelisks. They encapsulate multiple ambitions of power throughout the ages: in Egypt they were a demonstration of the pharaoh’s divine mandate; in imperial Rome they were booty that represented the triumph of Rome over Egypt; in the Renaissance the indecipherable hieroglyphs enchanted humanists as sources of hermetic mysteries.22 In the Worldlings an ornamented obelisk inscribed with hieroglyphs, containing “the ashes of a mightie Emperour,” is destroyed. The poet describes his vision in the concluding couplet: Je vy du ciel la tempeste descendre, / Et fouldroyer ce brave monument (Songe, 3.13–14), “A sodaine tempest from the heaven, I saw, with flushe stroke downe this noble monument.” Later Spenser would revise the lines in “Visions of Bellay” into “I saw a tempest from heaven descend, / Which this brave monument with flash did rend.” The “flushe stroke” and “with flash did rend” indicate the singularity of the event, an immediate destruction rather than a gradual decay. Alois Riegl, in his 1908 essay “The Modern Cult of Monuments,” distinguishes “intentional” and “unintentional” monuments: the first are artifices meant for perpetuity; the second’s meaning is determined not by their makers but by our modern valorization of them.23 In Riegl’s terminology Spenser’s “flash” renders the “intentional” monument an “unintentional” one. In other words, the moral insight offered by lyric fiction turns the public commemoration of a supposedly great man into a divine admonishment of human vanity.

Through allegory, physical destruction is reduced to moral exemplum; matter is converted into words. The effect is to preserve all the monitory power of the physical monument, while shrinking its grandeur and vanity to the less dangerous size of a few inches, where they can be duly chastised in an adjoining text.24 In this way the image, so distrusted in early Protestant art, is rendered harmless, even profitable; its pretensions are exposed, and its diminished attractions are made to serve the moral interests of the reader, who learns to be wary of fair exteriors.

In his first efforts at versification through translation, Spenser thus negotiates the mortality of all things through Protestant eschatology, crafting enduring verbal monuments about the ephemerality of physical ones. The juxtaposition of images and words illustrates the vanity of the phenomenal world; in fourteen lines the beginning stanzas narrate the destruction, and its moral principle is concentrated into a simple sententia, the “unveiling” of a truth about the world, such as in the sixth epigram: “Alas in earth so nothing doth endure / But bitter griefe that dothe our hearts anoy.” Spenser’s poetry, with the explicit goal of “delight and plesure of the eye and eares,” disenchants the false monuments, and by purifying the carnal senses replaces vain images with edifying, wholesome words.

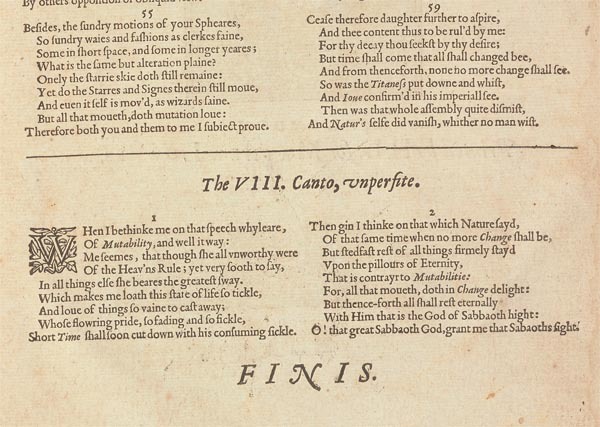

Figure 14. Geoffrey Whitney, Choice of Emblems (London, 1568). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Exegi Monumentum?

All physical monuments will decay or be destroyed; that is the commonplace wisdom in A Theatre for Voluptuous Worldings. Yet poetry itself is a mortal thing; writing too will someday disintegrate, its letters dissolving into the elements of the cosmos. This problem can be expressed in terms of what I call the antinomy of lyric hope: poetic creation is meant to endure, yet all human artifice will perish. The poet’s paradoxical response to destruction is to claim that his verses will outlast the material things in the world, even though poetry is a human artifice. We see this clearly expressed in Geoffrey Whitney’s celebrated Choice of Emblems (1586, fig. 14):

Scripta manent

If mightie Troie, with gates of stelle, and brasse,

Be worne awaie, with tracte of stealinge time:

If Carthage, raste: if Thebes be growne with grasse,

If Babel stoope: that to the cloudes did clime:

If Athens, and Numantia suffered spoile:

If Aegypt spires, be euened with the soile.

Then, what maye laste, which time dothe not impeache.

Since that wee see, theire monumentes are gone:

Nothing at all, but time doth ouer reache,

It eates the steele, and weares the marble stone:

But writings laste, thoughe it doe what it can,

And are preserv’d, euen since the worlde began.25

The main claim of this sonnet—textual endurance—is succinctly captured in the last two lines. In this perennial locus communis there is irony and tautology in its boasting of immortality as well as pathos in the impossible distance between its wish function and its realization for, interestingly, the sonnet does not go on to list all the great authors from Troy, Carthage, Babel, or Numantia. After all, we don’t have any that survive.

Seen from the vantage point of Christian doctrine, the poetics of immortality can be read as a hindrance to the “true immortality” of the eternal world, nothing but the vanity of writers. Spenser endeavors to escape this trap by skillfully deploying Neoplatonic allegory to imbue his lyrics with cyclical patterns of timelessness. A Spenserian moniment, then, is an artifice that mediates temporality and immortality, illusion and reality. Sonnet 51 of the Amoretti begins with the question:

Doe I not see that fairest ymages

Of hardest Marble are of purpose made?

For that they should endure through many ages,

Ne let theyr famous moniments to fade.

Why then doe I, untrained in lovers trade,

Her hardnes blame which I should more commend?

The passage opens with an image of material durability, but only to introduce a nobler, spiritual durability, the “hardnes” of his beloved. As in the Worldlings, the poet is able to abstract what he needs from material monuments—the “hard” metaphor—while at the same time draw a contrast between their slow-decaying deadness and the true, living immortality of the spirit, happily enshrined in verse. Praising a mortal beloved, no matter how pure or true, is ultimately a category mistake because it tries to impart timelessness to something that is inherently subject to time. But since love is a force of conjugation in the world, it can inspire the poet to celebrate its unifying powers with his worthy monuments.

“A Sonnet is a moment’s monument, / memorial from the Soul’s eternity / To one dead deathless hour,” Dante Gabriel Rossetti once quipped.26 The Pre-Raphaelite’s precious description illustrates the disproportion between an enormous monument, the brevity of time, and the miniature size of the sonnet. Amoretti 57 strikes a similar balance:

The famous warriores of the antike world,

Used Trophees to erect in stately wize:

in which they would the records have enrold,

of theyr great deeds and valarous emprise.

The poet’s response is to create something even better: “This verse vowd to eternity / shall be thereof immortall moniment / and tell her prayse to all posterity.” This metaphysical insistence on poetic durability must be read alongside the more transient “leaves, lines, and rymes” in the first sonnet.27 Since poetry is experienced in time, verse finds its fluid permanence in its sonic repetition and its written stasis. By investing the poem with a wish of timelessness, Spenser posits a paradox between the temporality of art and its ontology as an “immortall monument.” The poet’s creation thus counteracts the corrosive agent of time and is immune to the charges of idolatry, for the Amoretti precisely celebrate the sacrament of marriage.

True moniments for Spenser are supremely nonmaterial. Yet the poet expresses some anxiety about such possibility, for example, in Sonnet 75:

One day I wrote her name vpon the strand,

But came the waues and washed it away:

Agayne I wrote it with a second hand,

But came the tyde, and made my paynes his pray.

Vayne man, sayd she, that doest in vaine assay,

a mortall thing so to immortalize,

for I my selue shall lyke to this decay,

and eek my name bee wiped out lykewize. (1–8)

The beloved’s rebuke in the Amoretti calls to attention the fragility of Spenser’s poetic composition and the hyperbole of his wish. The poem additionally underscores the futility of repetition (“Agayne I wrote it with a second hand”), as well as the sameness of all mortal finitude (“I myselue shall lyke to this decay”; “my name bee wiped out lykewize”). The poet’s response at the end is “My verse your vertues rare shall eternize, and in the hevens wryte your glorious name” (11–12). But these conflicting metaphors—writing on sand and writing in the heavens—are surely signs of the ambiguity of writing, since the poet is literally writing on neither. The lyric thus stages its own anxieties of permanence by celebrating the instability of its inscription.

The relationship between material finitude and poetic permanence culminates in the last line of Spenser’s Epithalamion, where the poem itself is described as “for short time an endlesse moniment” (433). For Alastair Fowler and A. Kent Hieatt this phrase captures the quintessence of Elizabethan numerological symbolism.28 In an exquisitely crafted poem filled with precise prosodic, semantic, and phonic patterns, “for short time an endlesse moniment” mirrors the circular structure of a text that celebrates the constancy of diurnal and astral change, since the paradoxical juxtaposition of “short” and “endless” reinstates the chiastic relationship between transience and durability, natural time and artistic creation. The use of “endless” here instead of “timeless” is intriguing, for “endless” denotes a nonfinitude that is within rather than without time. In fact the specific day the poem commemorates is St. Barnabas’s Day, 11 June, which, according to the Elizabethan calendar, is the summer solstice, the most “endlesse” day of the year.

Spenser cleaves to the view that faced with the decay of all material things, the poet’s task is to craft immortal words that will survive the eventual destruction of the physical. This is articulated most fully at the end of The Shepheardes Calender:

The meaning wherof is that all thinges perish and come to

Theyr last end, but workes of learned wits and

Monuments of Poetry abide for ever. And therefore

Horace of his Odes a work though ful indede of great

Wit and learning, yet of no so great weight

and importaunce boldly sayth.

Exegi monimentum aere perennius,

Quod nec imber nec aquilo vorax etc.

Therefore let not be envied, that this Poete in his

Epilogue sayth he hath made a Calendar, that shall

Endure as long as time etc. folowing the ensample of

Horace and Ovid in the like.

Grande opus exegi quod nec Iovis ira nec ignis,

Nec ferum poterit nec edax abolere vetustas etc.

Loe I have made a Calender for every yeare,

That steele in strength, and time in durance shall outweare:

And if I marked well the starres revolution,

It shall continewe till the worlds dissolution.

The logic of these lines is clear: by means of his poetry the poet ensures his posthumous life. Yet it is certainly ironic that a work proclaiming precisely the changes of the seasons should have hopes of escaping the ravages of which it sings. Whereas earthly time is governed by the rotation of the sun, cosmic chronology is measured by the planetary revolution and the fixed stars, beyond which is the primum mobile, perpetual in its duration. While paying due homage to Ovid and Horace, Spenser subtly reframes this poetics of immortality in the Protestant apocalyptic mode. The crucial word here is “till”: “It shall continewe till the worlds dissolution.” Shakespeare too deploys this preposition in a grammar of resurrection: “So, till the judgment that yourself arise, / You live in this, and dwell in lovers’ eyes” (Sonnet 55). Spenser’s calendar and Shakespeare’s verse shall endure only up to the point of the world’s dissolution. After that presumably neither calendars nor poetry will be needed.

Against Antiquarianism: The Ruines of Time

If The Theatre for Worldlings is about material monuments turning into ruins, and the Amoretti about poetry wanting to become immaterial monuments, The Ruines of Time is about material ruins wanting to become verbal monuments. The ruin is Verlame, the personification of the historical Verulamium, a fallen city in Roman Britain. Although not even a “little moniment” of hers remains, she wants to be mourned and remembered in verse. Spenser praises the antiquarian William Camden for preserving in the medium of writing what has been lost in England. But since the objective of antiquarianism is to catalogue the material remains of the past, this project is problematic, since in the end time will “all moniments obscure” (Ruines of Time, 174). Ultimately the material preservation of antiquities is futile. Similarly the immortality topos, which classical poetics indulges, is here rejected as empty hubris. Poetry’s aspiration toward immortality is rectified by a series of apocalyptic visions that demonstrate the vanity of mortal ambitions: allegory thus trumps antiquarianism.

The poem begins by reflecting on how Verlame has utterly disappeared:

It chaunced me on a day beside the shore

Of silver streaming Thamesis to bee,

Nigh where the goodly Verlame stood of yore,

Of which there now remaines no memorie,

Nor anie little moniment to see,

By which the travailer, that fares that way,

This once was she, may warned be to say. (1–7)

Historically Verulamium represents an England under Roman control.29 For a national poet such as Spenser, she is the anti-London, a competing ideological voice that he will need to displace in order to establish English independence. As Verlame says, speaking to the mother city, Rome, “Of the whole world as thou wast the Empress, / So I of this small Northerne world was Princesse” (83–84). Verlame represents a pagan aesthetics that treats poetry as a means of ensuring personal and civic immortality. Clearly Verlame’s physical monuments have failed her; they have perished, and without them, her memory has perished as well, except in the mind of the poet. She is a name without an entity, a verbum without res.

She mourns for two things—the fact that all things in the world perish and the fact that these things are forgotten:

They all are gone, and all with them is gone,

Ne ought to me remaines, but to lament

My long decay, which no man els doth mone

and mourne my fall with dolefull dreriment. (155–58)

Verlame wants to be mourned, but she cannot be mourned until she is remembered. Yet this is highly problematic for Spenser, who believes that Verlame’s fall was just. Rebeca Helfer insightfully argues that Spenser’s view of the Roman Empire is more Augustinian than Virgilian, for he believed it was founded on pagan pride rather than providential grace; thus there should be no mourning for its righteous destruction.30 Verlame’s case for the “eternizing” power of poetry underscores the fantasy of her wish fulfillment. She holds up learning and poetry as means of “restoring the ruines” of the past but fails to make the case for why her ruins ought to be restored.

Though Verlame cannot be remembered in the way she wishes, it still behooves posterity to take some notice of her. For this reason Camden’s antiquarian efforts have not been in vain:

Cambden the nourice of antiquitie,

And lanterne unto late succeeding age,

To see the light of simple veritie,

Buried in ruines, through the great outrage

Of her owne people, led with warlike rage;

Cambden, though Time all moniments obscure,

Yet thy iust labours euer shall endure. (169–75)

The use of moniments here refers back to the opening lines in which Verlame as a physical entity no longer exists: “Of which there now remaines no memorie, / Nor anie little moniment to see.” What survives, according to these lines, is Camden’s record of them, not the monuments themselves. His “iust labor” is not so much that of an antiques dealer, who preserves only the physical objects of the past (which anyway will ultimately decay), but the project of writing that is more enduring, historical, and thus didactic.

Recent scholarship has amply shown how antiquarian research into England’s past contributed to a defined sense of nationhood in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.31 Indeed the stated goal of Camden’s Britannia (1577) was “to restore Britain to its Antiquities, and its Antiquities to Britain, to renew the memory of what was old, illustrate what was obscure, and settle what was doubtful, and to recover some certainty in our affairs.”32 For Spenser there must be a continuum between the interest in material ruins of Camden and his contemporaries John Leland, John Stow, and John Weever and the idea or moral of ruins point back to the fall of empires and forward to Christian eschatology. Pure antiquarianism, in contrast, was in love with the thingness of things—collecting and preserving indiscriminately. Bacon in The Advancement of Learning (1605) distinguishes between the antiquities, memorials, and perfect histories, and calls antiquities a “Historie defaced, or some remnants of History, which haue casually escaped the shipwrack of time.” (Incidentally Bacon was created baron of Verulam by King James I in 1618.) Though Bacon praises the antiquarians in their skills of “exact and scrupulous diligence and observation” in saving records and evidence from “the deluge of time,” their knowledge is by nature only partial and accidental.33 Spenser’s critique of antiquarianism too concerns its epistemological uncertainty:

High towers, farie temples, goodly theatres,

Strong walls, rich porches, princelie pallaces,

Large streetes, brave hourses, sacred sepulchers,

Sure gates, sweete gardes, stately galleries,

Wrought with faire pillours, and fine imageries,

All those (o pitie) now are turnd to dust,

And overgrowen with blacke oblivions rust. (92–98)

Since his role as “poet historical” strives toward a moral didactic end, he is suspicious of not only of the hubris behind monuments but also the obsessive campaign to preserve them. The desire for physical memorials is in fact a sort of vanity:

In vaine doo earthly Princes then, in vaine

Seeke with Pyramides, to heaven aspired;

Or huge Colosses, built with costlie paine;

Or brazen Pillours, never to be fired,

Or Shrines, made of the mettall most desired;

To make their memories for ever live:

For how can mortall immortalitie give? (407–13)

The answer to this question is poetry, specifically Spenser’s. Given that the material has vanished, what can one do except rely on poets to perpetuate what the material cannot? True immortality on earth is bestowed on those who have followed the paths of virtue:

All such vaine monuments of earthlie masse,

Devour’d of Time, in time to nought doo passe.

But fame with golden wings aloft doth flie,

Above the reach of ruinous decay,

And with brave plumes doth beate the azure skie,

Admir’d of base-borne men from farre away:

Then who so will with virtuous deeds assay

To mount to heaven, on Pegasus must ride,

And with sweete Poets verse be glorifide. (419–27)

Instead of immortalizing the dead, both a futile and a prideful endeavor, monuments should simply help us remember them, and in a way that puts timeless, ethical principles ahead of gaudy display. Spenser’s insistent message is that any attempt to achieve permanence within a fallen world is not only doomed but fraught with moral peril. Negotiating the pulls of preservation and critique, his lyrics are able to reject both material monuments and the “pagan” promise of the everlasting in favor of a Christian promise of true eternity, sweetened by the “Poets verse.”

Allegorical Architecture in The Faerie Queene

What is a monument and what is a ruin in Spenser’s magnum opus, The Faerie Queene? There are two levels of discourse: the content of the poem and the form of the poem. Things inside the narrative appear in various states of edification, deformation, and ruination: the landscape of Faerieland is filled with buildings on the edge of collapse; characters are often described with architectural analogies; and knights often become makers of ruins. The text itself is famously incomplete; Spenser envisioned twenty-four books but died having published only six, and the incomplete seventh was published posthumously.34 As Gordon Teskey has it, “Considered architectonically, within the well-established conventions of the epic poem, The Faerie Queene stands before us as a ruin, one that might have been completed but was not.”35 To bring posthumous apocrypha to compositional history, there circulated a legend in the eighteenth and nineteenth century that the concluding six books of The Faerie Queene were destroyed in a fire that consumed Kilcolman in 1598.36 It is as if the incompleteness of the poem and the fantasy of some lost totality are telescoped in its reception history. In other words, there are ruinous sites in The Faerie Queene, and then there is the monumental ruin that is The Faerie Queene itself.

The polysemy of moniment in the poem has an intriguing relationship to the definitions of Varro and later grammarians. In Isidore of Seville’s seventh-century Etymologiae, “monument” is defined thus:

A monument (monumentum) is so named because it “admonishes the mind” (mentem monere) to remember the deceased person. Indeed, when you don’t see a monument, it is as what is written (Psalm 30:13): “I have slipped from the heart as one who is dead.” But when you see it, it admonishes the mind and brings you back to mindfulness so that you remember the dead person. Thus both “monument” and “memory” (memoria) are so called from “the admonition of the mind” (mentis admonitio).37

By conflating psychic and physical memory, Isidore underscores the porous boundaries between the material and the mental. His citation of the Psalms further underscores the work of memory in the ethics of Christian charity. For Isidore the function of the monument as a memorial is not simply to provide a lasting record but to keep in living consciousness a constant devotion to what is no longer there so as to bring absentia into praesentia.

In the sixteenth century, however, monuments tended to be understood and defined simply as memorials. In Thomas Elyot’s Bibliotheca (1548), monumentum is defined as “a remembrance of some notable act, sepulchres, images, great stones, inscriptions, bookes.”38 In Thomas Cooper’s Thesaurus (1565), it is almost verbatim: “a remembrance of some notable art: as sepulchers, books, images, a memoriall, a token, a testimonie, A token pledge of love, chronicles, histories of antiquie.”39 Moniment is sometimes confused with muniment, “a document, such as a title deed, charter, etc., preserved as evidence of rights or privileges; an archival document” (OED), though both words span text and object. A monument defends (munire) by remembering (monēre).

John Weever states in Ancient Funeral Monuments (1609):

A monument is a thing erected, made, or written, for a memoriall of some remarkable action, fit to be transferred to future posterities and thus generally taken, all religious foundations, all sumptuous and magnificent Structures, Cities, Townes, Towers, Castles, Pillars, Pyramides, Crosses, Obeliskes, Amphitheaters, Statues, and the like, as well as Tombes and Sepulchres, are called Monuments. Now above all remembrances (by which men have endevoured, even in despight of death to give unto their Fames eternitie) for worthinesse and continuance, bookes, or writings, have ever had the preheminence.40

These words begin his massive nine-hundred-page tome—a collection of inscriptions from England and parts of the Continent—and are appropriately all-encompassing. The martyrologist John Foxe (ca. 1516–87) wrote an even more massive collection, Actes and Monumentes, a text reprinted many times and as influential as the Book of Common Prayer. Foxe insists that the most lasting monuments are not things but the deeds of Protestant Christians persecuted for the faith. Nearly four times the length of the Bible, the fourth edition of 1583 is itself a monument, having been called the “most physically imposing, complicated, and technically demanding English book of its era.”41

Varro’s manimoria, Isidore’s mentis admonitio, Weever’s “remarkable action,” and Cooper’s “notable art” are all about resisting the tilt of human memory toward forgetting. Foxe’s Actes and Monumentes is about commemorating the persecuted Christian community. What unites all these examples is an emphasis on the monument’s ethical demands and its physical durability. The history of the word in the longue durée of European consciousness represents an attempt to bring together materiality and memory in the movement from the local to the universal, from the here and now to the past or future, from the individual to the exemplary, from the tombstones that line the Via Appia to the Protestant martyrs who died for their faith.

Spenser, like Foxe, is suspicious of the physical sign as a stable carrier of meaningful memory, and trusts narrative more. The first appearance of moniment in The Faerie Queene occurs when the body of Hippolytus is described thus: “His goodly corps . . . Was quite dismembred, and his members chast / Scattered on euery mountaine, as he went, / That of Hippolytus was lefte no moniment” (I.v.38).42 The beginning of Book II has Sir Guyon encountering a dying woman and her child by a fountain: “That as a sacred Symbole it may dwell / In her sonnes flesh, to mind revengement / And be for all chast Dames an endlesse moniment” (II.ii.10.7–9). These two examples point to how, in William N. West’s words, “in the emergent idea of a ‘moniment,’ what is remembered is not merely imagined but really appears in the external world, only to be abandoned to a future that lacks the key to interpreting it.” Indeed of the almost fifty uses of moniment in Spenser’s poetry, the majority of them, West notes, are counterfactual; “that is, the word signals the absence of a suitable monument or even its erasure.”43 Nearly a third of the word’s occurrences point to the absence of a moniment, and another third are moniments of disaster or failure. Spenser’s monuments—physical or not—tend to lapse into ruin.

Taking note of Spenser’s rich play of words, I posit that in The Faerie Queene monuments and ruins represent the inner states of characters in the poem, characters who are always on the way to moral edification or ruination. In other words, monuments and ruins are not only material objects in the exterior landscape but also represent the individual characters’ moral standing. Through their actions (reminding, forgetting, preserving, eradicating), individuals claim their allegorical attributes, whether they be moralizing monuments or ruinous disasters. In the epic the monuments and ruins as actions and artifice coalesce. Beyond a poetics of ruins, then, there is also an allegory of ruins.

In Christian doctrine, since we are all fallen, we were ruins before we became monuments. This theme is explicit in Donne’s First Anniversary (1611):

We are born ruinous: poor mothers crie

That children come not right, nor orderly;

Except they headlong come and fall upon

An ominous precipitation.

How witty’s ruine?44

Donne puns on the Latinate meaning of “ruin” with “headlong come and fall upon” by explicitly acknowledging the already fallen state of human nativity. These sentiments are close to Spenser’s, for whom there is a close correlation between moral failings and forms of ruination. He uses “ruin” and its variants (“ruinate,” “ruined,” “ruinous,” “ruins”) eighteen times in The Faerie Queene; in almost every instance the word refers to people, not buildings. Already in verse three of Book I, Spenser underscores the broken nature of mortals. Redcrosse, the very first character we meet, is described as “ycladd in mightie armes and siluer shielde, / wherein old dints of deepe woundes did remaine, / the cruel markes of many a bloody fielde / yet armes till that time never did he wield” (I.i.1). Too young to have lost a battle, Redcrosse is already marked by the inheritance of original sin. Although born a ruin, he will become a monument of holiness. The telos of the central characters is to personify the “ensamples,” or moniment of their virtues. As Milton would say in On Education (1644), “The end then of learning is to repair the ruines of our first parents.”45

Spenser sees a close correlation between moral failings and forms of ruination. Indeed similes between people and structures are common:

Or as a Castle reared high and round,

By subtile engins and malitious slight

Is vndermined from the lowest ground,

And her foundation forst, and feebled quight,

At last downe falles, and with her heaped hight,

Her hastie ruine does more heauie make,

And yields it selfe vnto the victours might;

Such was this Gyaunts fall, that seemd to shake

The stedfast globe of earth, as it for feare did quake. (I.viii.23)

In Book V a collapse is described:

Like as a ship, whom cruell tempest driues

Vpon a rocke with horrible dismay . . .

So downe the cliffe the wretched Gyant tumbled;

His battred ballances in peeces lay,

His timbered bones all broken rudely rumbled,

So was the high aspyring with huge ruine humbled. (V.ii.50)

Interestingly the poem never uses “ruin” or its variants to refer to remnants, only to moments of ruination. (I will explain later why its annihilation leaves no traces.) And these moments of destruction are certainly pervasive: the House of Pride is built on a shaky foundation; Alma’s castle is besieged; Malbecco’s castle is on fire; the House of Busirane simply vanishes. Close to the beginning and ending of the poem are the figures of Kirkrapine and the Blatant Beast, the entropic forces at the margins that seek to unravel the entire fabric of the text. Imminent destruction is the basic condition of existence in Spenser’s world.

In other words, all architectural constructions in The Faerie Queene are unstable: they exist as potential ruins, poised precariously between the prelapsarian garden and eventual apocalyptic clearance. As Faerieland is the earthly setting of a fallen world that encompasses both good and bad places, would-be ruins exist between order and chaos. Morally corrupted places are not ruins in the usual sense; they are much more insidious, always inhabited, deceptively whole on the outside, gaudily ornamented inside, teetering toward ruin rather than already ruined. Dangerous places in the poem are simulacra, like the duplicitous figures of Archimago, Duessa, and the False Florimell, providing opportunities to the protagonist to exercise his or her powers of moral insight.

Part of the training Spenser’s knights undergo is hermeneutic: that of learning to read corruption beneath beguiling architectonic surfaces. Tellingly the word “architect” is a hapax in the poem. In the opening line of Book II, Archimago is described as the “cunning architect of cankred guile” (II.i.1). “Architect” surely means schemer, and the adjective “cunning” underscores Archimago’s deceptive nature, as manifested in his misleading appearance. In examining such shimmering illusions, the crucial interpretative move is the ability to distinguish the modes of seeming.

This ability is crucial in Book I, and nowhere more so than in the House of Pride, first introduced as “a goodly building brauely garnished, / The house of mightie Prince it seemd to be” (iv.2) and given a lavish description:

A stately Pallace built of squared bricke,

Which cunningly was without morter laid,

Whose wals were high, but nothing strong, nor thick

And golden foile all ouer them displaid,

That purest skye with brightnesse they dismaid:

High lifted vp were many loftie towres,

And goodly galleries far ouer laid,

Full of faire windowes, and delightful bowres,

And on the top a Diall told the timely howres.

It was a goodly heape for to behould,

And spake the praises of the workmans witt;

But full great pittie, that so faire a mould

Did on so weake foundation euer sitt:

For on a sandie hill, that still did flitt,

And fall away, it mounted was full hie,

That euery breath of heauen shaked itt:

And all the hinder partes, that few could spie,

Were ruinous and old, but painted cunningly. (I.iv.4–5)

The adverb “cunningly” in line 2 anticipates the “cunning architect” Archimago. The reality of the House of Pride is revealed in the contrast between its façade (“golden foile . . . loftie lowres”) and substratum (“weake foundation . . . sandie hill”). “On the top a Diall told the timely howres” reminds us that even this seemingly opulent building is subject to mortality, though its inhabitants may arrogantly suppose otherwise.

Interred in its underground dungeon is a gallery of fallen mighty princes:

All these together in one heape were throwne,

Like carkases of beastes in butchers stall.

And in another corner wide were strowne

The Antique ruins of the Romanes fall;

Great Romulus the Grandsyre of them all,

Proud Tarquin, and too lordly Lentulus,

Stout Scipio, and stubborne Hanniball,

Ambitious Sylla, and sterne Marius,

High Caesar, great Pompey, and fiers Antonius. (I.v.49)

The interior of the House of Pride is less a temple in ruins than a set of temples dedicated to ruins. Seeing this exquisitely curated antimonumental collection of ruins, the dwarf, “made ensample of their mournfull sight,” discovers the dungeon and tells Redcrosse that they must flee. Only in the last stanza do they discover that strewn about the castle is a “donghill of dead carkases.” And consonant with the theme of reality and deception, the very name “house of Pryde” is withheld until the last line of canto v. Gleaming externally but festering internally, the House of Pride is what Rosalie Colie would call an “anamorphic” image with no single, natural point of view.46 The “cunning architect” deforms images, and it is incumbent upon the reader to correct them, not with the faculty of sense perception but with that of the intellect.

The House of Ate in Book IV is another site where ruins are instructively displayed. The walls are hung “with ragged monuments of times forepast . . . of all which ruines there some relicks did remain” (IV.i.21). It is a museum of the fallen, displaying “signes” of the vanished empires of “antique” Babylon, “fatall” Thebes, Rome “that raigned long,” “sacred” Jerusalem, and “sad” Ilion. Whereas in their natural condition ruins rush toward irresistible decay, the House of Ate preserves ruins qua ruins and sets into a theological narrative the bric-a-brac of history. “Spectors, great cities ransackt, and strong castles rast” are curated into “ragged monuments of times forepast.” The human ruins of The Faerie Queene—the once-proud Tarquin, Caesar, Pompey and Antony—stand out as types of their reduced essences, much like the sequence of the prideful fallen in Dante’s Purgatorio 12. In Spenser they are made into an intentional museum, suspended in their ripe ruinous fixity, a collection of fragments conserved in a coherent, exemplary order. In Reformation Germany Protestant churches sometimes housed a Götzenkammer, “idol chamber,” in a parody of Catholic collections of reliquaries of saint’s bones and other remains.47 Spenser’s catalogue of the fallen empires is his “idol chamber”: “Of all which ruines there some relicks did remain . . . The monuments whereof there byding beene” (IV.i.24).

Constructing Monuments

Having looked at all these negative images of monuments, let us turn to a more positive episode. Of the forty-six times Spenser uses moniment or its plural in the poem, its richest occurrence, eleven times, is in Canto X of Book II, when Arthur reads from the Moniments of Briton.48 It is here that Spenser articulates most fully his vision of a true, enduring monument. Spenser’s poetics of the moniment, instead of seeking to escape the ravages of temporality (what Shakespeare in the Sonnets calls “sluttish time”), actually reinserts itself back into temporality, presenting what I call an ethics of the monument. By retrieving the etymological roots of monēre Spenser recasts moniment into an ethical mandate of memory. Since ruins make us think about mortality, they make us think about what it means to live. His monuments—instead of being funerary—serve a living moral purpose. In other words, his monuments are things of the past that are still firmly grounded in the present, always geared toward moral admonishment and self-reflection.

Scholars such as Judith H. Anderson, Bart van Es, Andrew Escobedo, and Rebeca Helfer have seen this episode as paradigmatic of Spenser’s articulation of the work of memory.49 Jennifer Summit argues that the scene of the library is Spenser’s response to the destruction of texts wrought by the Reformation.50 John Speed in his 1611 History of Great Britaine laments that during this time monastic buildings were “laid open to the general deluge of Time, whose stream bore down the walles of all those foundations, carrying away the shrines of the dead, and defacing the Libraries of their ancient records.”51 This inspired a generation of antiquarians who attempted to salvage the textual remains of the past. In a 1568 letter to Matthew Parker, the Privy Council ordered him to survey all surviving medieval books: “such historical matters and monuments of antiquity, both for the state ecclesiastical and civil government.”52 During the reign of Mary Tudor, John Dee pleaded for a foundation of a “Library Royall” so as to preserve “all the famose & worthy Monuments that are in the notablyest libraryes, beyond the sea as in Vaticana of Rome [and] S. Marc of Venise.”53 Though this proposal was ignored, it was repeated by a group of antiquarians who urged Elizabeth to “preserve divers old books concernynge matter of hystorye of this Realm [such as] original charters and monuments.”54 But as Summit points out, their plans of restitution were highly selective, for there is a difference between the “monuments of antiquity” that they preserved and the “monuments of superstition”—the breviaries, Psalters, mass books, Catholic prayer manuals, and legends of the saints—that they suppressed.

I would add to the status of textual monuments the importance of actual funerary monuments in early modern England, the lavish tombs erected in thousands of churches. Exquisitely composed of sculpted forms, architectural ornaments, painted heraldry, and inscriptions, the tombs celebrated the worthy and virtuous lives of noblemen.55 When Spenser saw monuments, these were their most ostentatious examples. Prior to the Reformation, Erwin Panofsky argues, funeral monuments were prospective objects in which the living interceded with God and the saints on behalf of the dead for mercy and remembrance. The Protestant conviction that the salvation of the dead could not be altered forced tomb construction merely to prolong their glory on earth and display their family’s prominence.56

In this episode of Briton moniments, I see Spenser’s allegory negotiating these three different forms of monumentalizations: the archives of the library, the tombs of the nobility, and the classical tradition of poetic immortality. Instead of physical residuum, Spenser’s moniments are an allegorical reduction of one’s moral essence in which individual signs become universally legible.

Arthur reads the Moniments of Briton in the library of Eumnestes, which serves as an allegory of the human brain. Eumnestes (“good memory”) is endowed with “infinite remembraunce” and possesses “old records from auncient times” in his sprawling library of “antique Regesters.” He is “halfe blind, / And all decrepit in his feeble corse, / Yet liuely vigour rested in his mind” (II.ix.55.5–7). Embodying the duality that is the nature of Alma’s castle, Eumnestes himself is a combination of infinite memory and finite record; his records are “incorrupted” yet “all worm-eaten, and full of canker holes” (II.ix.56.7, 57.9).

Briton moniments is thus also a muniment; by defending (munire), it remembers (monēre). Here we have a realization of the antiquarian’s fantasy—the totality of the past carefully documented and collected in a single room. Yet how does one represent the encyclopedia of memory, Eumnestes’s “infinite remembraunce,” in a finite canto of sixty-eight stanzas? David Lee Miller notes that “Eumnestes lacks a principle of elimination.”57 “Tossing and turning” his records “withouten end” (II.ix.58), he keeps on writing and writing:

And things foregone through many ages held,

Which he recorded still, as they did pas,

Ne suffred them to perish through long eld,

As all things els, the which this world doth weld,

But laid them vp in his immortall scrine,

Where they for euer incorrupted dweld. (II.ix.56)

But to what purpose? Outside this archival utopia, how does the scribe determine what to write about and what to leave out? The slippage between event, memory, and representation occurs in all media: in the moniments of historians such as Holinshed, Stow, and Leland; in the monuments left in the landscape, such as Stonehenge and Ludgate; in Spenser’s own conceit of Eumnestes’s scrolls.

Spenser’s solution is that as a redactor, he himself prunes the total memory of Eumnestes into a finite, morally useful shape. Spenser, “poet historical,” is the redactor between the library’s “immortall scrine” and the reader. Beginning with ethical acts that are then translated into ethical memory, the poet’s task is to pick from the interminable sequence of kings and knights those shining exemplars, or what he calls “brave ensample,” that one can emulate. They should be distilled into monuments. In the catalogue proper, he does this by adding two further meanings of “monuments” that are both prior to and broader than the textual or architectural sense: first, progeny are described as monuments to their parents; second, great deeds themselves are described as monuments to their doers. Instead of immortal “timeless” monuments, Spenser offers us mortal “endless” monuments, echoing Epithalamion’s “for short time an endlesse moniment.” On the legacy of Lud, Spenser writes:

He had two sonnes, whose eldest called Lud

Left of his life most famous memory,

And endlesse monuments of his great good:

The ruin’d wals he did reaedifye

Of Troynouant, gainst force of enimy,

And built that gate, which of his name is hight,

By which he lyes entombed solemnly. (II.x.46)

The poet conflates two meanings of “monument” in one: Lud’s gate (the westernmost gate of London Wall) is his tomb, hence his magnificent physical monument, yet it is also the memorial to his great deed of expelling the enemies’ forces. Spenser suggests that true moniments are the records of the exemplary actions of an individual, which constitute the real patrimony that is bestowed on future generations, not an impressive entrance to the great city, or even the lavish splendor of a Westminster Abbey or a St. Paul’s, what Shakespeare calls “the rich proud cost of outworn buried age” (Sonnet 64) and Spenser himself terms “such vaine monuments of earthlie masse” (The Ruines of Time).

The use of monument in the ethical sense turns its meaning from memory to action, from the past to the present. We see another example of this when Guyon reads the story of Elfinor, a descendant of Constantine in the “Antiquitee of Faerie lond”:

He left three sonnes, the which in order raynd,

And all their Ofspring, in their dew descents,

Euen seuen hundred Princes, which maintaynd

With mightie deedes their sondry gouernments;

That were too long their infinite contents

Here to record, ne much materiall:

Yet should they be most famous moniments,

And braue ensample, both of martiall,

And ciuil rule to kinges and states imperiall. (II.x.74)

This stanza suggests an almost biblical blessing in the correlation between good deeds and the generation of children. The grammatical construction here, “That were too long their infinite contents / Here to record, ne much materiall: / Yet should they be most famous moniments,” puts the question of monument and the question of the poet’s efforts into an intriguingly subjunctive relationship. Even after gathering the ruins of antiquity into an archive, the task of sorting through them is impossible because of their “infinite content.” Hence poetic remembrance is a process of distillation, to the point that monuments actually, and appropriately, lose their individuality and merge into the larger moral fabric of the poem, so that they become “famous moniments” or “braue ensample.” Neither the antiquarian, solely preoccupied with preserving everything without discrimination, nor the royal historian, prejudiced in favor of recording only things that serve to glorify the dynastic past, have the poet’s gift of discernment.

Briton moniments situates Spenser in the tradition of John Foxe, who uses “monuments” in the title of Actes and Monumentes. For Foxe monuments are not the tombs of mighty personages but rather the deeds of the numerous Reformation martyrs who would have been forgotten had he himself not preserved them. Foxe’s monumentalization of their acts has a didactic purpose, for the actions of the martyrs are precisely those worthy of memory and emulation. This notion has a long legacy: even in archaic Greek commemorative poetry, the true monument of a fallen warrior is not the physical marker over his body but the exemplum he leaves behind.58 Similarly for Spenser lasting fame is derived from noble deeds.

This hermeneutical tension between life and the recording of it is exposed when Prince Arthur is reading the prophetic Moniments of Briton. Arriving at his own life, he abruptly stops. In a moment of perfect mise-en-abyme the reader and the read converge:

After him Vther, which Pendragon hight,

Succeeding There abruptly it did end,

Without full point, or other Cesure right,

As if the rest some wicked hand did rend,

Or th’Author selfe could not at least attend

To finish it: that so vntimely breach

The Prince him selfe halfe seemed to offend,

Yet secret pleasure did offence empeach,

And wonder of antiquity long stopt his speech. (II.x.68)

These lines mark a vanishing point, a rupture in the text. As Van Es observes, “Spenser’s wording—Succeeding There—matches the grammatical oddity described in the text Arthur is reading. Nowhere else in The Faerie Queene do we find a capitalized adverb not preceded by a full stop.”59 In other words, the Moniments of Briton and Spenser’s textual monument come to a screeching halt in the face of life. As Arthur finishes the register, he finds himself on its edge; it is incumbent on him to continue what “th’Authour selfe” cannot. “The Authour self could not at least attend / to finish it” because Arthur’s life is not finished, and he is supposed to be, in this irresistible pun, his own Authour. And as all of Britain’s history is a preparation to his anointed arrival, it is he himself who must read these moniments and fashion his own moniment.

As we have seen, the most common monuments in Book II are the deeds of worthy individuals. There is, however, a notable instance of an actual architectural monument. In the final section of the chronicle, between Caesar’s arrival and Pendragon’s reign, there is a reference to Stonehenge, “whose dolefull moniments who list to rew, / Th’eternall markes of treason may at Stonheng vew” (II.x.66.8–9). The origins of these stony monoliths are as dark and murky as the origins of Faerieland. Although Spenser asserts that Stonehenge marks the treacherous slaughter of Vortigern’s men and the mass grave containing the victims of Saxon treachery (“Soone after which, three hundred Lordes he slew / Of British bloud, all sitting at his bord” [II.x.66.9]), antiquarians generally held this story to be questionable. Camden reports the story in his Britannia but concludes, “About these points I am not curious to argue and dispute, but rather to lament with much griefe that the Authors of so notable a monument are buried in oblivion.”60 Spenser, however, need not let his moral be bound by facts. Whereas antiquarianism falls silent in the absence of physical evidence, its ignorance exposed, the poet’s imagination can invent its own etiology.

The moral of Stonehenge and the divergent accounts of its origins demonstrate that monuments offer competing and contradictory accounts of national history: for the victorious the ruins are the totem of the enemy’s destruction; for the defeated, an ignominious reminder of shame. Stonehenge, at once a surviving structure, a grave, and an imprint of the “eternall markes of treason,” constitutes the irony of a perfect countermonument: the Neolithic formations have survived, but their message to posterity is a famous mystery. The anonymous Stonehenge is an inversion of Lucan’s dictum that I discussed in chapter 3: “Even the ruins have perished,” Etiam periere ruinae (9.969) and “Every stone has a story,” Nullum est sine nomine saxum (9.973), for here is an abiding ruin, utterly mysterious to all. Whereas the ruins of Troy and Rome are overly determined with meaning, the enigma of Stonehenge mocks us with its impenetrable silence. In this case Spenser imagines a future in which remembrance does not recuperate the past and offers a way to recognize that a physical monument (with a u) without ethical moniment (with an i) is nothing but an orphaned sign seeking signification.

Erasing Monuments

Stonehenge is a unique example of a monument without a story. Stories without monuments, however, occur frequently. Having looked at the construction of monuments, let us turn to their destruction. Kenneth Gross suggests that the most intriguing moments in the poem are those that grapple with iconoclasm: “Spenser always multiplies and opposes perspectives in his poem, always sets one mode of imagination against another—not for the sake of rhetorical display but to keep his ideals from turning into idols, his tropes into traps.”61 The iconoclast, after all, often intentionally leaves traces of what he has destroyed: a statue is decapitated, but the body remains; the face of an icon is obliterated, but the icon still hangs in the vestibule. The ancient precedent is the Roman practice of damnatio memoriae—what remains is as important as what was destroyed.62 Spenserian iconoclasm, however, is usually complete and wholesale; no physical traces of the monument survive, only textual traces, that is, Spenser’s own writing.

The destruction of the Bower of Bliss is perhaps one of the most memorable moments of ruin making in the poem and has attracted many prominent readers. As medieval and renaissance gardens responded to what Terry Comito calls a “deep desire for a mythic potency of space, for possessing an original and timeless point of reality,” the Bower is at once a garden and a future ruin.63 And the monument that precedes its ruination is, not surprisingly by now, not ostentatious at all: it is but a tiny piece of the knight Verdant’s equipment, no longer visible:

His warlike armes, the idel instruments

Of sleeping praise, were hong vpon a tree,

And his braue shield, full of old moniments,

Was fowly ra’st, that none the signes might see,

Ne for them, ne for honour cared hee,

Ne ought, that did to his aduauncement tend. (II.xii.80)

In this instance it is clear that “monument” does not mean a showy tomb or sepulcher. In fact the OED cites this as the first attestation of the definition: “A thing that serves as identification; a mark, sign. Also: a thing that gives warning; a portent.” The erased monuments on Verdant’s shield represent not only historical but moral amnesia; literally these moniments are a record of Verdant’s knightly deeds, but they also suggest a warning in the etymological sense of monēre. This is Christian imagery, originating in Paul’s catalogue of the armor of God in the Letter to the Ephesians. The shield is meant to represent faith, with which the believer extinguishes the fiery darts of temptation hurled at him (Eph. 6:16). But now the shield, faded and disused, has lost both the power to defend and the power to warn. Ignored by its sole audience, it has become a symbol of the utter laxness of his moral attention.

The description of Verdant’s “braue shield” bears comparison to two striking moments of ekphrasis in Latin epics, the death of Turnus in Virgil and the petrification of Phineus in Ovid, for in divergent ways all three cases deal with the various stages of monuments and ethical action. At the close of the Aeneid, Aeneas must decide the fate of Turnus. Until this point Aeneas hesitates to punish his enemy, but the sudden sight of his friend Pallas’s stolen belt fills him with rage: “Aeneas, as soon as his eyes drank in the trophy, that memorial of cruel grief, ablaze with fury and terrible in his wrath,” Ille, oculis postquam saevi monimenta doloris / Exuviasque hausit, furiis accensus et ira /Terribilis (12.944–47). The use of monimenta here is remarkable for the word does not so much denote the material sense of a fixed enduring object as retain a sense of didactic warning. Pallas’s monimenta, like Verdant’s, are portable, part of a warrior’s necessary wardrobe. In the Aeneid visual spectacle does what speech cannot: the belt, depicting the slaughter of forty-nine of the fifty sons of Aegyptus by the daughters of Danaus on their marriage night, motivates Aeneas for revenge. The pictorial image on the stolen armor serves as a typological justification of Aeneas’s ethically problematic decision; as the daughters slew the sons of Aegyptus, so Aeneas exacts vengeance on Turnus. The belt as a tiny monument is a catalyst for action, bringing the poem to its shuddering conclusion.64

Whereas Aeneas slays Turnus because of a monumental reminder, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses the hero Perseus turns his adversary into a literal stony monument. Perseus’s contest with Phineus, the former fiancé of Andromeda, is an Ovidian rewriting of the Virgilian duel. The Greek hero says to his suppliant:

Quin etiam mansura dabo monimenta per aeuum,

Inque domo soceri semper spectabere nostri

Ut mea se sponsi soletur imagine coniunx. (5.227–28)

But I will make of you a monument that shall endure for ages; and in the house of my father-in-law you shall always stand on view, that so my wife may find solace in the statue of her promised lord.

Ovid plays on the poetic immortality topos by putting this grim taunt into Perseus’s mouth; the petrified Phineus will be a monument remembered for all time. In this case, though, it is the victim rather than the victor who is caught by the power of sight, and rather than inspiring action, the sight of Medusa’s head puts a permanent end to action. Here the everlasting monument is the person himself; nonmimetic art and life are encased in the same stony material. Phineus’s afterlife is metamorphosed into an ever-fixed stillness.

Like Aeneas, and unlike the weak Verdant or the hapless Phineus, Guyon turns seeing into doing. Stephen Greenblatt calls iconoclasm “the principle of regenerative violence” whereby the “act of tearing down is the act of fashioning.”65 In the final stage of his moral education Guyon must resist being a ruin by becoming a maker of ruins:

But all those pleasaunt bowres and Pallace braue,

Guyon broke downe, with rigour pittilesse;

Ne ought their goodly workmanship might saue

Them from the tempest of his wrathfulnesse,

But that their blisse he turn’d to balefulnesse:

Their groues he feld, their gardens did deface,

Their arbers spoyle, their Cabinets suppresse,

Their banket houses burne, their buildings race,

And of the fairest late, now made the fowlest place. (II.xii.83)

Spenser describes an act of violence that is almost as perfectly symmetrical and orderly as the syntax in which it is narrated. The use of “race” here suggests that it is the just corrective to “fowly ra’st” moniments of Verdant. Similarly “deface” echoes Verdant’s “certes it great pittie was to see / Him his nobilitie so foule deface” (II.xii.79).

A skeptical reader might wonder what these epic moments have to do with ruins and monuments beyond their lexical coincidence, but they are important to the chapter’s argument for they reach back to the etymological meaning of monēre in the ethical sense at critical moments of epic action. Physical deformation coincides with moral judgment. Materiality gives way to allegory. In Virgil art inspires slaying; looking at a monument, the belt of his dead friend, inspires Aeneas to kill Turnus. In Ovid the slain becomes art; Perseus kills Phineus by turning him into a statue. In Spenser moniments are erased and are in need of recall by an external agent—here the Knight of Temperance. Read in the light of the classical tradition, the episode in the Bower of Bliss puts the making, breaking, and interpreting of monuments front and center: Guyon must destroy the Bower lest he be destroyed by it.

“Lefte No Monument”

Guyon’s clearing of the Bower is complete—wounds in Spenser’s world leave no scars behind. As such, ruination in the poem is always the activity itself rather than the aftermath, similar to the destruction in the Complaints. In the expansive landscape of The Faerie Queene we find no desolate tombs, broken Roman triumphal arches, or fallen cities as we do in The Ruines of Time. Nor are there the echo-haunted cemeteries of the Duchess of Malfi or the anachronistic monasteries of Titus Andronicus, to point out just two notable ekphrastic instances of ruins on the early modern English stage.66 Why?

First, there is a generic reason why a Bury St. Edmond filled with damaged sacramental fonts would be an impossibility in Faerieland. Because the poem hews closely to the conventions of romance, in which topography and temporality are malleable, places do not provide any sense of fixity. Furthermore ruins would be quite incongruous in Faerieland, since as ciphers of a dismembered past they signal a historicity that posits a rupture between time then and time now. There seems to be no pastness of the past in Faerieland, no disjuncture between antiquity and the present. Freed from the burden of a specific reality, characters within the poem seem not to suffer from the nostalgia of historicity. While the extradiegetic voice of the narrator is often tinged with nostalgia for a golden age, within the diegetic narrative the frequent use of the temporal markers “whilome” and “antique” or allusions to mythological figures serve not so much to distance history as to flatten it. Razed castles and disenchanted palaces cast a retrospective shadow not for the characters, who are usually going forward, but for the reader, always interpreting backward.

As I mentioned earlier, the targets of the English iconoclasts were never completely destroyed: the hands and feet of the Apostles are chipped off a choir screen, but their effigies remain. In Elizabeth’s reign a Marian rood was covered with canvas and the royal arms painted over it. An indulgence prayer book for the dead was still used, but every mention of the pope’s name was meticulously blackened. The name of St. Thomas Becket was deleted from an antiphonal with the slenderest of pen strokes.67 What is lost can still be seen and touched; hence its capacity to summon nostalgia or fear of return is greater than its utter disappearance. Far from annihilating them, the iconoclast damages idols with aesthetic care. In this sense his conscious decision to leave objects in their injured state is a deeper mockery than complete erasure, for it taunts their former status as efficacious artifacts worthy of adoration. A fallen idol thus becomes its own mocking monument.