Actually, the story of our creation, the creation of the new world, never happened. Maybe that was why we told it to ourselves over and over again. We didn’t have a written language or one that we could use to translate our lives for the city people.

We thought that multitudes would join us. Groups from Hashomer Hatzair, volunteers from overseas, workers of the world. We didn’t know that, in 1960, we were born to a star whose light had long since died and it was now on its way to the sea. We didn’t know that the kibbutz movement had been at the height of its prestige during the Wall-and-Tower period in the 1930s, and that before the establishment of the state in 1947, the kibbutz population was the highest it would ever be—7% of the entire Jewish population. In ’48, we were already decreasing, and in the ’70s, we were only 3.3% of the entire population.

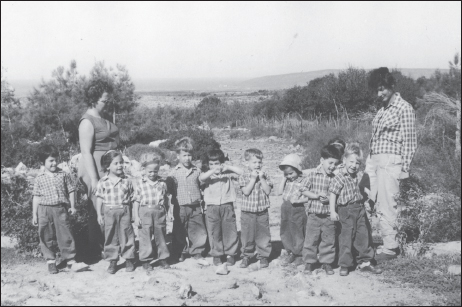

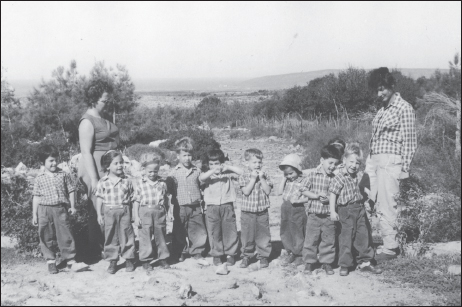

The Narcissus group on an excursion;

Yael pictured fifth from right, the smallest child wearing the hat.

We didn’t know that our star illuminated only itself. We thought that we were growing and building.

We were born in 1960 on Kibbutz Yehiam, the most beautiful kibbutz in the world—green with pines, purple with Judas trees, yellow with broom plants—founded in 1946 on a hill below a Crusader fortress. We were born to the Narcissus Group. We were sixteen children in Narcissus, eight boys and eight girls. We were a gentle group, most of us born to older parents, the Hungarian founders of the kibbutz who built it together with an Israeli group of Hashomer Hatzair.

We said the names of the children in our group quickly, all strung together, in order of age. There was also the alphabetical order of surnames, the bourgeois order that could only be used by strangers who didn’t know anything, or by doctors, when, for instance, we were waiting our turn to see the dentist who came from Nahariya or the Krayot near Haifa. In an indifferent tone, he used to dictate to Miriam Ron, who was in charge of the clinic, the bad news that was repeated every year: seven cavities, or nine, or twelve. We had so many cavities and so few sweets. And we all wore braces made for us by the orthodontist. We also waited on line for him until Miriam called us in the alphabetical order of our surnames, and he too came from Nahariya or the Krayot.

We hadn’t exactly chosen the name Narcissus, even though we did ultimately vote for it, unanimously, in the first grade. The group’s name went with us everywhere—it hung on the bulletin board and was written on the name tag sewed onto our clothes in the communa, the clothing supply room. Every group had its own color and its own Roman numeral. We were brown and our number was X.

When we chose the name, we still weren’t familiar with the rules. We didn’t understand that we had to have the names of flowers or something else in nature. When we were born, there were already about 120 children on the kibbutz, divided into groups by age. And although the groups before us were called Rock, Grove, Cyclamen, Pomegranate, Pine, Oak and Terebinth, we still didn’t understand. We never noticed.

We suggested a variety of names, most of them ending with “Gang.” “The Explosion Gang,” “The Forest Gang,” and all the other adventurous sounding names. The metapelet directed us, at first gently, then more firmly to the world of flowers until we fell into line and chose Narcissus. I don’t remember the name of the other flower we were considering; I think we already realized that it didn’t matter if we were Narcissus, Anemone or Chrysanthemum—the names given to the groups that came after us. We understood that it was like choosing white or carrot-orange sandals that had the same shape.

Other kibbutzim like ours throughout the country, from the Galilee to the Negev, chose the same names. And we all dreamed about Noriko-san, the little girl from Japan.

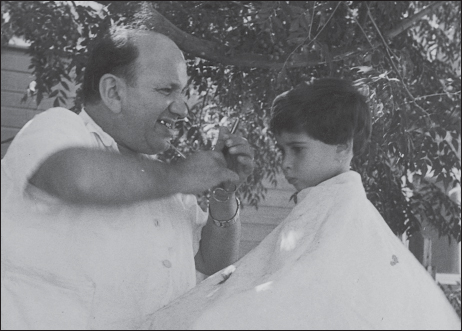

Fishel from Nahariya was the kibbutz barber.

Every once in a while, at intervals that we could not understand, he would come to us, the Narcissus Group. Amongst ourselves, we called him Dr. Fishel, maybe because of Dr. Zuriel, the kibbutz doctor, who also came from Nahariya, and Dr. Pollack, his replacement who also came from Nahariya, and Dr. Lieber, the dentist. We thought that maybe everyone in Nahariya was a doctor. But Fishel wasn’t a doctor; nor was he one of the Naharyia Yekkim, the Jews of German descent who lived in that city. He was Fishel the Barber, and he lived in the transit camp next to the Nahariya hospital.

Fishel, the kibbutz barber, at work.

We hated having our hair cut, but we suffered mainly from Fishel’s lies. It never occurred to us that you could lie without blinking an eye and even repeat the same lies over and over again. We sat in regular chairs for our haircuts. There were no adults around and we really didn’t understand the order in which we were called. Whenever it was another child’s turn, the sheet was flapped around his shoulders like a bib, quickly, and there wasn’t a lot of time to be afraid. It was clear that after he left us, Fishel moved on with his equipment to cut other children’s hair. Only much later did we learn, almost by chance, that all the professionals—the barbers, doctors, dentists—worked not only with the children, but with all the kibbutz members. They came, worked for a flat rate, and left.

As he worked, Fishel asked each child what he wanted: Balloons? Candy? Then he memorized each answer (or so we thought) and promised to bring balloons or candy on his next visit. That’s how it was every time. And he never brought anything. But we believed him each time and cried with disappointment when no gifts arrived the next time either. Fishel, after all, came from Nahariya, a city that was all candy and chocolate-coated bananas in the stores and rolls and butter in Hans and Gila’s café. Enchanting coaches drawn by horses rolled along Haga’aton Boulevard, whisking passengers from one place to another. All the best things in the world were there, and he probably never gave us a thought as he walked past all the display windows.

But Fishel must have hated us much more than we hated him, and he certainly didn’t have the money to buy us presents. We didn’t even know whether he had children of his own. We didn’t know a thing about the homes of our dentists in Haifa and the Krayot; we thought that all the city people were rich. We didn’t know that they worked at a flat rate and lived in transit camps.

We drowned in a sea of our own sweat. The sounds of the recorders, mandolins and cymbals deafened us. We were burned by the banner of letters that were doused in kerosene and set aflame: “For Zionism, Socialism and the Brotherhood Amongst Nations,” like the slogan of the newspaper Al Hamishmar that was put in our parents’ mailboxes everyday. But we never connected that to our neighbors in Yanuh, the Druze village visible at the edge of the horizon on the eastern side of the fortress. We used to go hiking there with our teacher, crossing our wadi, the Yehiam stream, hearing about the arbutus and Judas trees, and, in a demonstration of the brotherhood amongst nations, walked up to Yanuh’s enormous school for a visit. There, they always gave us brightly-colored candy and invited us to see their classes. We reciprocated by inviting them to visit us. When they came, we gave them wafers. We played soccer. We beat them by so much, 13:1 or 12:0, that we were dizzy with victory for days.

We didn’t know that thousands of people lived in Yanuh, that the town had no infrastructure, that they had to study Bialik, the Hebrew poet. They told us, but we didn’t study Bialik, so we didn’t understand what that meant. We knew nothing. Neither Hebrew nor Arabic. Yanuh was two kilometers away, but light-years separated us.

And we knew nothing about our neighbors in the development town of Ma’alot, except that, starting in the seventh grade, we had to help them with their homework once a week for two hours. We knew nothing about Lebanon on the other side of the border.

We knew nothing about Kabri either, the kibbutz we had to pass on the way to see the doctors in the Kupat Holim clinic in Nahariya. Because Kabri wasn’t in Hashomer Hatzair.

We walked around like fakirs,3 both children and adults, on the surface of a moon nobody wanted to discover. We believed that we would pluck stars and the stars, like fireworks, would light up the skies over all the countries in the world. And workers would march by their light as if they were torches, and equality and justice would descend upon the world. Our legs hurt so much from the effort that we could focus only on the march itself. We forgot who we were bringing equality to, who we were forging peace with and who deserved justice. We drank our sweat and helped no one.

Volunteers used to come to us from all over the world. They came on their school vacations, filled with enthusiasm about what was called “lending a hand,” helping us with our work. We played volleyball with them, spoke our broken English, played guitars, tried lying on a waterbed. Look, the world is coming to us, so blond, fair and polite. They worked, took an interest in our lives and then went back overseas. We went on with our lives.