The old-timers and adults that we, the children, considered important were, in certain cases, totally different from the ones immortalized in the kibbutz’s official history, in The Jubilee Book or various other commemorative projects. We already knew when we were children that on our kibbutz, Yehiam, and on all the kibbutzim from the Sea of Galilee to the Negev, there was always a rotation in the higher, desirable positions, such as secretary, work coordinator, and the like.

We didn’t notice, neither then nor later on, that there was no rotation in other occupations. No one ever asked to switch jobs with the women who did the laundry; no one ever coveted the Sisyphean work of the potato peelers, who spent decades sitting on low stools beside huge pots in the kitchen. There was never any rotation for the woman who cleaned the public showers and toilets for years. On the kibbutzim, those jobs were designated the “service branch” (to differentiate them from the profitable and productive jobs in the fields or factories), like an HQ battalion whose soldiers remain in camp to outfit tanks and prepare food for the hungry officers and troops returning from maneuvers or the battlefield.

Women working in the communa, the clothing storeroom.

Women working in the kitchen.

Rotation, one of the marvels of our system, protected the prominent members who moved from one major function to another, and turned its back on the members of the lower castes, keeping them trapped in place.

Most of the service providers were from the Workers group. The name hadn’t been chosen deliberately to be such a dazzlingly ironic contrast to the First of May group, whose members were among the founders of the kibbutz and members of the movement even before the war, in Hungary.

The members of the Workers group were Zionist refugees of the war who joined Hashomer Hatzair in Hungary after the war, and immigrated to Israel under the movement’s sponsorship. They said later: “To this day, it is not clear what had more of an effect on us: the ideological arguments or the good chocolates and cigarettes.” They arrived in Yehiam two years after it had been established, several months after the War of Independence battles that had been fought there. They were full partners in the building and development of the kibbutz.

Even after we, members of the kibbutz, left, and even after the volunteers and many members of all the other groups were gone, members of the Workers group remained. The largest percentage of those who remained in Kibbutz Yehiam at any time was from the Hungarian Workers group.

Our contact with the grown-ups was dictated by the logic of our everyday lives and included only those who played a part in them: teachers, metaplot,4 workers in the communa (the clothing storeroom), the shoe repair workshop and the dining hall—people from the service branch.

The heroes of our mythology were almost all members of the Workers group because they were the ones who worked on the kibbutz land, in the communa, in the kitchen. They were the ones who sometimes stopped beside us on the sidewalk and gave us an affectionate pat. And they were also the only ones who allowed their children to stay in their biological homes for a while after they ran away from the children’s house, and gave them candy. We didn’t know then that they were from the Workers group, and neither my brothers nor I knew that our mother was from the First of May group and that our father had come to the country earlier, in 1939, after a family council convened in Vienna and decided that all the young people would leave without delay.

After all, the past is irrelevant on kibbutzim. Everyone—whether born in a village in Hungary or in Budapest, in Vienna or Haifa—is equal in the eyes of the system.

The head of the Hungarian old-timers in the Workers group, the leader of all the old-timers, the person in first place, miles ahead of everyone else, was Pirosh. Though he did not take part in the battles with the Arabs in the War of Independence (members of the Workers group arrived in Yehiam after that war), or establish an agricultural branch, and was never appointed kibbutz secretary or work coordinator, we knew that without him, the kibbutz would collapse.

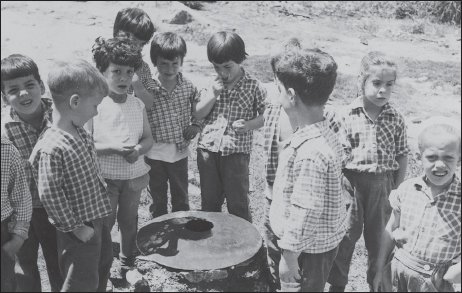

Twice a year, a line of our children, like a huge centipede, would go to the shoemaking workshop and try on the new shoes that Pirosh made for us.

Pirosh means “red” or “redhead” in Hungarian, but when we were born, he was already more bald than redheaded. Pirosh cursed whenever he wanted, gave our thighs a hard, painful slap whenever he wanted, and chose his helpers in the colbo, where we got supplies, from among the girls in the seventh grade or higher, based on the size of their breasts. He said it as if he were talking about awarding medals to the girls he described as having “large balconies.” No one on the kibbutz ever spoke like that, only Pirosh. He was the shoemaker, he chose the movies we saw and screened them, and he was in charge of the weapons storeroom and the colbo. Each of those was almost a full-time job.

The shoemaking workshop was a small shed on the edge of the kibbutz, whose walls, and especially its high, slanted ceiling, were covered with pictures of starlets—that’s what Pirosh called them—that he clipped from various magazines. All of them were glamorous women with plunging necklines, huge breasts and broad smiles. Pirosh taught us their names. We didn’t know whether that shed was really so different from other kibbutz buildings, or whether it seemed so different to us because of the starlets, the smell of leather and the shoe-stretching machines. The workshop consisted of two rooms, and Pirosh sat in the first room with his constant assistant, Meir S., an excellent professional shoemaker, who people said had also been one in Hungary. Meir S. would stop working only to smile his bashful smile and ask how we were, and he was never irritable. They sat on either side of a huge worktable that was littered with tools and shoe parts.

They worked with their entire bodies, and their mouths were always full of nails, as were all their pockets.

The other room contained the stretching machines, many boxes of shoes, and two small stools on which we would sit in front of Pirosh to try on the new line he made for us twice every year—high shoes in winter and sandals in summer. We came to choose a color: sandals in white or carrot-orange for girls, and brown for boys; shoes in red or brown for all of us. The shape was the same for all the children of the Kibbutz Artzi movement.

No one knew exactly what Pirosh’s story was. He was such a presence that questions seemed unnecessary. But we asked anyway. Pirosh was single. Sometimes our centipede, shod in red or brown, would stop near a group of old-timers and ask why Pirosh was single, why he didn’t have any children. They didn’t answer us. It was as if our question passed, like a paper plane, over the heads of those busy people rushing from place to place, without ever landing. He was single, and that was that. Once, someone told us that it was a case of unrequited love. We considered every aspect of that answer, but couldn’t remember who said it and whether he really meant it. Maybe he just wanted to get rid of us. Non-practical matters were never discussed. Nor were Pirosh’s hard, painful slaps of our thighs when he measured our new shoes and explained: “I’m measuring you thoroughly.” We laughed at his jokes, collected them and repeated them over and over again.

The Narcissus group preparing bread in the backyard.

Pirosh pronounced all the names of Hollywood actors and actresses with a Hungarian accent, and we thought that not only did he know their names, but he actually knew them. The pictures that lined the walls of the shoemaking workshop revealed to us the cleavage of Raquel Welch and company, and in that décolletage, we saw an escape, a hint that a different kind of life was possible. The idea of hanging pictures of women with their cleavage exposed was so out of the ordinary that Hashomer Hatzair did not have a clause in its rules of conduct prohibiting it. And that’s another reason we were so proud of Pirosh. In our heart of hearts, we knew that he worked an additional job for us that was much more important than all the other services he provided: For us, he symbolized the existence of other worlds—L’Hiton (an entertainment magazine), Tel Aviv, Hollywood and New York. As if he were actually a subversive one-man international commune, a clever one never seen as dangerous because it never had to declare itself. That’s why no one noticed how much Pirosh’s existence and his pictures seeped into our minds.

Pirosh’s various occupations allowed him to travel a great deal, though never at the expense of work, as he always pointed out. He merely took advantage of the hundreds of vacation days the old-timers had accumulated, the fruit of their endless labors. He went to Tel Aviv, where he saw dozens of movies. Then he brought them to us from the Movie Department.

Until the end of the sixth grade, we saw the movies with the Children’s Society. Apart from his job of choosing and screening the movies, Pirosh was also in charge of censoring them. There were no parents, metaplot or teachers at the screenings. Only we and Pirosh were there, like in the shoemaking workshop.

Every other week, he brought a movie from Tel Aviv: Annie Get Your Gun, Lassie Come Home, Winnetou, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. He didn’t censor vulgarities, only frightening scenes. When a scene he considered frightening was about to appear on the screen, Pirosh would simply order all the children in the third grade and below to leave. That’s why we never saw the Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz. Suddenly he turned on the lights and sent us out.

When we were in the seventh grade, we joined the adults on movie night, which the entire kibbutz eagerly awaited. Once a week we’d sit in rows in the large dining hall. The screening would be delayed, the way daily lectures and Friday night dinners in the dining hall were delayed, until everyone agreed on whether to open or close the windows. Those arguments were like a silent movie being shown over and over again before the main feature. First the window-closers would get up, and without a word, close them and sit down. Then the window-openers would get up, open them and sit down. The two groups operated in a sequence known only to them.

No one ever intervened, neither the children nor the adults. We all knew that this had also come from there. (Most of the Hungarians, from both The First of May and the Workers groups, came from there. And there—my mother told me once when I was sick—the Danube froze over in winter. And there—another member once told us—the Danube was red with blood because so many Jews had been shot and thrown into it all at once.) Somehow, we all accepted the explanation of the getting-up-and-opening and the getting-up-and-closing offered by one kid in our centipede to another: Anyone who was in the camps or holed up in a cramped hiding place needed to open. Anyone who was in an open area or who was set upon by dogs had to close. We would wait. For those who closed and those who opened.

After the windows issue was resolved, Pirosh would begin the screening, the first reel threaded and ready to go. Carmi, one of his constant apprentices, son of Meir S. from the shoemaking workshop and the only person Pirosh trusted, would help him. Pirosh had begun training him for the job when he was seven.

In the middle or towards the end of the second reel—because the first part of the screening was always longer than the second—Pirosh’s voice boomed as he separated the word into individual syllables: IN-TER-MI-SSION. He pronounced the word with the proper diction he’d worked hard to achieve for only that single word and had polished endlessly until it reached perfection. When the five-minute intermission was over, the screening began again with no delays or postponements. Even if the members pleaded, he never waited.

Though Pirosh insisted on good behavior, we could still hear clearly the shouts of the people in the last row who accompanied the movie with a unique soundtrack of comments and jokes.

The Movie Department of the Histadrut Labor Federation, from which all the kibbutzim and moshavim5 took the movies, was located on Sheinkin Street in Tel Aviv, three houses away from our apartment. “Our apartment” on Sheinkin in the center of Tel Aviv wasn’t exactly ours, but that’s what we, all the kibbutz members and children, called it. All the kibbutzim had apartments in the city, where we vacationed with our biological families, and where the “activists” spent nights—that’s what we called the members who worked outside the kibbutz. The nicknames we gave to people who held those positions were always as dynamic as the name of our eternally young movement, Hashomer Hatzair, the Young Guard.

Zili from Ashkelon rented the apartment to Kibbutz Yehiam at a very cheap rate. We thought that Zili was a millionaire. He wasn’t a millionaire, but his brother, Diuri, was a member of the Workers group on Kibbutz Yehiam, and he wanted to contribute and help kibbutzim.

We believed that when Pirosh went to Tel Aviv and saw fourteen movies in three days, he thought about which of them would be especially appropriate for us. We didn’t know that the decisions were made long before that by the people in the Movie Department of the Histadrut. The movies were passed from one kibbutz to the other. On all of them, just as on our kibbutz, the members gathered once a week in the dining hall—and in summer, on the lawn of the clubhouse—to watch a movie.

Due to copyright agreements, the movies were copied (from 35mm to 16mm) two or three years after their city premieres.

The French people on the kibbutz occasionally held discussions on cinema and politics and ran the Classic Cinema Club, where they discussed Eisenstein or Bertolucci. But they had difficulty finding classic films because those agreements, as well as copyright problems, required the Department to destroy the copies after five years.

On our planet, the present obliterated the past and the future. The classics were destroyed and the contemporary films had not yet been copied for us. We saw all the movies in our own particular order.

It was the Repertoire Committee of the Histadrut Movie Department that chose which movies to copy. The Movie Department had, in fact, a monopoly on 16mm films in Israel.

Not only did the Department lack a large, important part of classic cinema, but erotic movies weren’t included in the repertoire either.

The French members protested against that situation at meetings of the Classic Cinema Club. They asked: Why aren’t films like Emanuelle, The Last Tango in Paris, or What Do You Say to a Naked Lady allowed to be screened, while every karate movie is in the Department, along with every Western? Are karate movies and all the other bourgeois family movies preferable to erotic films that raise many existential questions, they wondered out loud during a discussion that preceded the screening itself.

After a few years, those movies arrived as well.

Pirosh also ran the projector at the meetings of the Classic Cinema Club. He never got involved in the discussions. He was in favor of screening all the movies in the world.