Kibbutz Yehiam stands on an isolated hill at the foot of a Crusader fortress whose beauty can be seen from far and wide.

In his book 1967, Tom Segev describes the founding of our kibbutz, Kibbutz Yehiam, quoting from the diary kept by Yosef Weitz, a leader of the Jewish National Fund, whose son, Yehiam, was killed in a Palmach operation in 1946:

Three months after the Night of the Bridges, Yosef Weitz traveled to the Arab village of ‘Zib, north of Acre, and from a distance observed the place where Yehiam had been killed. “I couldn’t go right there and prostrate myself and search for the drops of blood which the earth had soaked up,” he wrote. Looking east, he saw the remnants of Qala’at Djedin, or the Heroes’ Fortress, an impressively tall stone tower built by the Crusaders that had become a stronghold of the Galilee ruler Daher el’Omar. The sun was setting, the tower “glimmered and lit up the entire area, all the way to Haifa.” And then Weitz knew; he swore that this would be where Yehiam’s monument would rise. A new Jewish pioneering settlement had to be built here, in this place, for defense, for forestation, and for agriculture. “The fortress shall be renewed and it shall be ours,” he wrote, “and above it shall fly the name of Yehiam, a token of innocence and dedication and sacrifice, and by its side an eternal flame shall send light into the distance.” This endeavor, Weitz told his wife, Ruhama, would be their solace. Thus Kibbutz Yehiam was founded.

Every Independence Day eve, we stood on the lawn in front of the dining hall in the U-shaped formation that allowed everyone to see everyone else, and we all wore white shirts with yizkor (memorial) pins that had a picture of the Red Everlasting flower on them. Gilad gave the signal with his trumpet from the dining hall roof, where he stood near the flag that had been flying at half mast for Memorial Day and then raised for Independence Day. On the lawn below, a bass voice cried out: “Kibbutz, attention!” And then: “Kibbutz, at ease!” Then we all went up to the fortress along a path lined with torches.

Standing in the large open area beneath the fortress, we raised our heads to look up into the sea of flames. Words made up of huge letters that had been strung along iron wires were set aflame. Every year, we were surprised once again by the fireworks that lit up the sky, some of which were made from weapons and grenades that had been collected all year, developed and improved especially for that night.

The entire history of the fortress, from the time of the Crusaders in the twelfth century to the Independence Day battles, was written on the blue Nature and Parks Authority placards placed in front of the fortress and inside it.

Our silo, the silo of a Hashomer Hatzair kibbutz, and yes, our pigsty, were built at the foot of the fortress, similar to the way the Christians or Muslims, in a newly conquered land, build a church or mosque near an older church of a different denomination, or on the ruins of a mosque they have vanquished. But the Crusader fortress remained standing under the sky, on the top of the hill, looking out over the entire breadth of the landscape, its existence revealing history—a beautiful, imposing presence that continued to exist in parallel to our own religion, which was aimed at creating a future different from anything humanity had ever known before, and destroying the past.

The members took advantage of every opportunity to tell themselves and us the story of how the kibbutz was built. Sometimes they danced or sang it, sometimes they sat on the stage and recounted it to one and all. As if the story about us, that we told to ourselves all the time, on kibbutz holidays, on quiet evenings, in newsletters, in letters, in end-of-year plays, expanded our brief history, thickening it, justifying it, adding meaning to our existence.

We loved the plays and songs more than the reality of our daily lives, but if they lectured the history to us, we didn’t understand a thing. The events didn’t seem to connect to each other. The continuity was broken. We couldn’t connect the Holocaust with the War of Independence, and with the fact that it all happened to our parents. When exactly, where exactly. They showed us the places in the fortress where they had been entrenched, and the scorched bullet holes.

The story that the old-timers loved to tell the most, as if they had to tell it, was about the early days of the kibbutz. They told it to us on Saturdays, or when they were at work or walking through the fortress with us. They told it to each other on kibbutz holidays and in newsletters.

It began in Kiryat Haim, where the old-timers lived in May ’46. There were about ninety members, most of them in their twenties, on a plot of land that had a single building and tents on it. They were called Kibbutz Hasela (“the rock”) then.

Hasela consisted of two totally different core groups: the Meadow group of the Israeli movement, and the First of May group, made up of former members of the Hashomer Hatzair movement from Hungary and Slovakia.

As was customary in all Hashomer Hatzair kibbutzim, while the members were preparing to settle in their permanent home, they worked outside the kibbutz: in the port, in the Naaman factory, in the Mivreshet factory, in bourgeois city homes as cleaners and laundresses, and doing any other odd jobs they could find that would earn money for the kibbutz.

Later on, everything happened quickly: the members of the various groups still hadn’t had time to bridge the huge gaps between them—they included former members of the Hashomer Hatzair group of Rehovot and the Ben Shemen boarding school, as well as the Hungarians and the Slovakians, who had arrived only a few months earlier from the hell of World War II. They were six months into their year-long training period, learning to cohere into a well-functioning group, when senior delegates from the Kibbutz Artzi Economic and Settlement Committee arrived at Kibbutz Hasela in Kiryat Haim with news: they would have to move to a new destination and settle there urgently.

The new destination—Djedin—was surprising, as was the urgency of the move. The Kibbutz Artzi spokesmen said that they would not paint a pretty picture of their new home: none of what they needed to survive could be found in Djedin. There was no water, no land, no food, no weapons, no way to support themselves there. It was a true wilderness in the heart of a hostile population.

They said they knew that the groups had not been together long enough to cohere into a true kibbutz. They said that there were severe problems with the water supply to that particular point, that under such conditions the army should be posted there, at the foot of a fortress with no land, but a Hashomer Hatzair kibbutz was preferable to any military unit. And the more time they spent describing the overwhelming difficulties and the beauty of the fortress, the more attached the members grew to the place, even before they saw it. After the kibbutz held marathon discussions, during which Avraham Herzfeld, Yaakov Hazan and Yosef Weitz spoke, a decision was taken to move to Yehiam, which still bore the name of the ancient fortress, Djedin. At week’s end, a large majority of the members of Kibbutz Hasela voted in favor of the Kibbutz Artzi proposal: an urgent move to Djedin in the Western Galilee.

It was decided that the children and most of the women would remain in Kiryat Haim, in Kibbutz Hasela, until basic conditions for housing had been established at the foot of the fortress.

On November 27, 1946, only one week after those marathon discussions, the men climbed up to Djedin, carrying all their equipment on their backs.

The members of Hasela changed the name of the kibbutz to Yehiam, after Yehiam Weitz.

Everyone in the Yishuv (the Jewish population of Israel prior to the establishment of the state) knew of the Weitz family. Yosef Weitz was one of the heads of the Jewish National Fund and had been involved in establishing many settlements, including kibbutzim in the Western Galilee and the Jerusalem neighborhood of Beit Hakerem, where he lived with his family.

On Yehiam, we called him the father of the kibbutz. The old-timers sent him radishes, packed in a shoebox, from the first crop planted at the foot of the fortress, and we, the Narcissus children, celebrated his eightieth birthday, the very same year we celebrated our tenth. It was then that our teacher taught us the meaning of the word gevurot, which literally means “strength” or “might,” but has come to represent anyone who reaches the age of eighty.

If “aristocracy” hadn’t been such an ignominious term in Hashomer Hatzair, Yehiam Weitz, Yosef Weitz’s son, could be called the personification of the Eretz Israeli aristocracy. He was the son of parents who came from prominent families (Weitz, on his father’s side, Altschuler on his mother’s), and the brother of Professor Raanan Weitz, one of the leaders of the settlement movement and the Chairman of the Jewish Agency Settlement Department.

Yehiam was born in Yavniel, grew up in Beit Hakerem, attended the Gymnasia Ivrit in Rehavia, and was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. He worked in Kibbutz Mishmar Haemek before he left for the University of London to study botany and chemistry. He graduated with honors and was accepted by the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. When World War II broke out, he left his studies and, as one of the first company commanders of the Palmach, became one of the models for the iconic image of the Palmach soldier.

In 1946, on the night between June 16th and 17th, the Night of the Bridges operation was carried out, in which Palmach units went out to blow up eleven iron bridges, roads and train tracks at eight locations in the country, in order to cut off the access of troops from neighboring countries. Yehiam Weitz’s unit came under attack by Arabs guarding the bridges. He was the first to be hit, and died immediately, while the other thirteen soldiers were killed when bullets hit the explosive materials they were carrying and the railway bridge collapsed on them after they took shelter between its columns.

He was twenty-eight when he was killed, married to the singer Rema Samsonov. No one had been named Yehiam before him. Many, including Kibbutz Yehiam itself, were called Yehiam after him.

Tom Segev describes his extraordinary funeral:

He was buried just as he had lived, as the son of his father, a prominent figure in a very small society: almost everyone knew everyone and many were related. “Jewish Jerusalem in their thousands yesterday accompanied Yehiam, the son of Yosef Weitz, to his final resting place,” reported the daily newspaper Davar. The national flag was draped over the body. Thirteen men had been killed with Yehiam that night, but their bodies had been shattered, thus his funeral stood for theirs, too. The public was called to take part: in Haifa, where the funeral procession began, all work came to a halt, transportation stood still, schools were closed, In Jerusalem, the procession could hardly make its way through the crowds. Yehiam was buried on the Mount of Olives.

The newspapers continued to follow avidly the heroic story of the Yehiam settlers, and Rafael, a member of Yehiam’s Meadow group wrote in his diary:

When we arrived in Yehiam, we divided the kibbutz into two: one part, in Yehiam, consists mainly of men, and is a proud place that stars in the newspapers, a mecca, where all hardships are endured with love. The other part is in Kiryat Haim. Mainly women. They work at odd jobs, earn money for the kibbutz, take care of the few children and yearn for the day they can come to Yehiam.

Yehiam did not have a battle tradition; we were not forced to know about the battles it had fought, nor did we learn its history in an organized manner. We tried to listen again each time it was mentioned because we wanted to know, but we never understood. Sometimes, we felt that, for a brief moment, we had suddenly grasped what preceded what, but over and over again, we lost hold of that understanding. It was as if it sank into the fortress cisterns, like the stone used to demonstrate gravitational force for us: it fell and fell until it landed on the bottom of the cistern with the dull sound we waited for expectantly so we could estimate the depth.

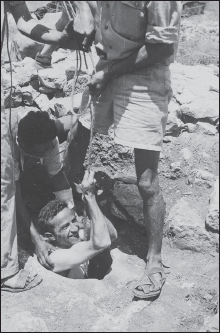

Zvi Gershon and Natan Flesh told us that in the beginning, the members who came to Yehiam lived in the fortress. The water they managed to collect in its ancient cisterns was brown, moldy, and rife with mosquito eggs. In order to purify it for drinking, Natan Flesh poured airplane fuel into the cisterns and ignited it. Sometimes, if they used the wrong amount of fuel, all the drinking water, sparse to begin with, was lost. Sometimes the members lost consciousness, one after the other, when they went down into the ancient cisterns to clean them.

Kibbutz members cleaning old water cisterns in the fortress.

There was no other water, neither in the fortress cisterns nor anywhere else on the kibbutz land. Transporting it was difficult and complicated, and it was done on the backs of donkeys. A member would send a Morse code signal from the top of the fortress to Kiryat Haim, where the rest of the members were, telling them how much water to bring. Then they would calculate how many people were needed to carry the container from the van, which could come only as far as Hagaaton Valley, but couldn’t remain there for long because of the gunfire. From there, they had to carry everything on foot, and every day, they had to deal with the question of how many people there were to carry it all on their backs, and how many donkeys would have to help them.

They told us that the kibbutz was isolated and cut off, and the road leading to it hadn’t been paved yet. Cars drove to Hagaaton Valley, and people, donkeys and mules walked from the valley to Yehiam along an overgrown path that became negotiable because of constant use. In winter, on rainy days, walking required great effort. The split between Kiryat Haim and Yehiam separated families, members, friends and even the members of various committees. The two parts of the kibbutz communicated through signals sent mainly at night. There was a machine in Yehiam that threw shafts of light to a distance of forty kilometers, but only if the weather was calm and the air bright and clear, with no rain or fog. Morse code was used to communicate, and generating the electric current needed to signal was complicated. They used car batteries, which they had to charge every few weeks. That was how they sent their regards, personal messages and requests for supplies. Coded messages regarding security matters were sent on wireless radios.

At 1:30 AM on November 29, 1947, one year and two days after the first members arrived at Yehiam, the signal station in the fortress received a telegram from Kibbutz Hasela in Kiryat Haim:

From that night on, as a result of the partition plan adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, the borders of the Hebrew state had been drawn south of Acre (on the banks of the Naaman), and Yehiam was therefore inside the Arab state.

Tom Segev writes in 1967:

At the end of 1947, war broke out. It resulted in the establishment of the State of Israel, and its territory included Yehiam as well as West Jerusalem and other areas not intended for it under the partition plan. Yosef Weitz believed that the success of the Zionist enterprise necessitated the removal of the Arab population from Palestine. During and after the war, he was involved in deporting Arabs from territories conquered by the IDF, preventing refugees from returning, and forcibly transferring Arabs within the state. In the 1950s he was instrumental in attempts to encourage Israeli Arabs to leave the country. He continued to believe in the “transfer” of Arabs to the end of his days.

Every now and then, we went up to the fortress, and one of the old-timers would retell the story of the War of Independence battles for us or someone else he was showing around, and bits and pieces of what he said stayed in our minds. Sometimes, we managed to grab hold of the beginning of the plot, other times it melted in our ears as soon as we heard it, or it was only the end that we grasped. The cisterns, the malaria, the shooting; in which convoy had the members been killed, the one to Yehiam or the one to Keziv; was it an attack on Yehiam, or in the Auschwitz camps. One convoy merged with another; an armored vehicle with a train.

At the outpost during the Independence War, 1948.

Zvi Gershon, who was chosen from the members of Yehiam to be commander, ordered all the others to sleep with their shoes on and guns cocked from that night on. He told us that everyone knew it was only a matter of time before Yehiam—a small, isolated, mountain settlement accessed by only a single road that wound through Arab villages—would come under attack. Blowing up one bridge over the Gaaton River would be enough to cut it off.

About a month and a half after the night of the Partition, on January 11, 1948, Yosef Weitz wrote in his diary:

From the morning on, I met with representatives of the settlements in the area. I am especially concerned for Yehiam. The sparse rainfall has not brought water to the cisterns, and to this day, the members endanger themselves by transporting water from Nahariya. It is essential to level and pave the road, which will require a budget of 15,000 liras. And more buildings and work are needed. They are isolated and alone. Can they endure? And for what? This question troubles me from time to time, shaking the unshakeable view I held before the United Nations decision that it is good for us to have agricultural settlements in the Arab state. Has there been a weakening in my faith that the day is approaching when the Western Galilee will be ours? For without that faith, there is no point in sacrificing and investing. I would like to do something for this place, but I fear the objections of others. Especially of the Settlement Department. And the young men here are so nice and good, and they never hesitate.

Nine days later came the attack that surprised everyone with its intensity: At dawn on January 20, 1948, the kibbutz was attacked by a regiment of the Arab Liberation Army, under the supreme command of Qawuqji. Troops from neighboring Arab countries had been mobilized into that regiment by Adib Shishkali in Lebanon. The attack raged for six hours, as the regiment attempted to invade and conquer Yehiam.

During the attack, the bridge over the Gaaton River was blown up. Yehiam was inundated by rifle, machine gun and mortar fire for the entire six hours.

From Tree Hill, where we used to take walks almost every week with Rivka, our teacher, the members of Yehiam recognized Adib Shishkali, the well-known military leader, who later became the president of Syria. He sat astride a white horse, commanding his troops. That attack on Yehiam, the first one of such magnitude in the War of Independence, is considered an extraordinary one to this very day. The attacking army was repulsed after many of its number were killed and wounded. In Yehiam, four were killed and six wounded. Also killed were six guards traveling in the armored van that accompanied the water transport to Yehiam. It came under attack on the road and burned.

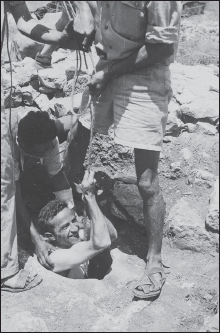

Zvi Gershon said that, in addition to attempts to airdrop supplies to the kibbutz from light planes, a supply convoy was occasionally sent from the coast.

On March 27, 1948, one such convoy, an especially large one that included ninety soldiers, set out from Nahariya on its way to Yehiam. Halfway there, it was ambushed by the people of the adjacent village, al-Kabri.

In Yehiam, they heard the noise and saw the columns of smoke, but did not know what was happening. Nor did they know exactly how many people there were in the convoy and which members of the kibbutz had joined it. (Members who had managed to get away from the kibbutz to arrange things and organize supplies, or those who were coming from Kiryat Haim for a short visit, always joined the convoy because that was their only way of getting to and from Yehiam.)

Zvi Gerson relates that the first armored vehicle, fitted with a barricade breaker, reached Yehiam. There were fourteen fighters inside it, including the company commander, Eitan Zeid, who was killed, the severely wounded armored vehicle driver, and another wounded man. The fighters who managed to reach the kibbutz didn’t know how the rest of the convoy was faring. Neither coded nor uncoded communications reached the members in Yehiam with further information about the fate of the people who were in the other vehicles.

Forty-seven of the fighters and passengers in the convoy were killed. The old-timers always said that, of all the terrible nights Yehiam had experienced, that one was the worst.

After the convoy was wiped out, Yehiam came under total siege. A large number of all the weapons in the entire Western Galilee had been destroyed in the convoy, and no one knew how long the supplies and arms in Yehiam would last.

In a letter written by Avri Sela on April 2nd, less than a week after the convoy disaster, he described the situation in Yehiam: the failed attempts to prepare a landing strip that would make airdrops of food easier; the endless barrages of bullets being fired at them; the shortage of weapons and their feeling of apprehension in the face of Qawuqji’s large army, which was concentrated on Tree Hill, 1,452 meters from the fortress. He wrote about the bereavement:

Shall I write to you about our mood? It must surely be clear to you. There’s Haim Drori, the soul of the kibbutz, work scheduler, purchase coordinator, janitor, alert to everything going on in the kibbutz. He was so alive before that it’s difficult for me to talk about our lives without complaining that Haim didn’t do this or that the way it should be done. And Laki—only three weeks ago he came with the new car, smiling as usual. He was so good, so devoted. And Rafael, tall, wild Rafael, always writing. Such a deep thinker. We have lost three dear members in a single day. It is difficult to imagine life without them.

Two days later, on April 4th, Qawuqji’s troops attacked Yehiam again. They opened fire just as the plane was dropping supplies and kept at it for several hours, but made no attempt to invade the kibbutz.

Shosh Shoresh, the wireless operator and one of the few women in Yehiam during the war, said that it wasn’t until Tarshicha and the Western Galilee were conquered in the Hiram Operation on October 30, 1948, that the war in Yehiam ended. On that day, she sent the last two telegrams to Nahariya: “At 7:05, the white flag was raised on the Tarshicha mosque,” and “I’m closing the station until further notice.”

When we were in the third grade, every Tuesday evening we would sit in our classroom with Hencha, who brought stenciled songbooks with her and taught us the songs in them. On those evenings, we didn’t sing about the Budyonny Regiment riding into battle, but we sang slower, sadder songs, like “The Fisherman’s Daughter.” We also learned new words from the song “aflutter” and “incomparable.”

An airplane dropping supplies for Yehiam,

when it was under siege by Arab fighters.

Hencha would occasionally stop the singing and tell us about the first children on the kibbutz. She was those children’s first metapelet, back when the kibbutz was still in Kiryat Haim and was called Hasela. She told us that one of the things that set the kibbutz apart from its very beginning was the fact that it had children older than the kibbutz itself. And the four of them were allocated a place in the only building on the plot of land in Kiryat Haim that the members had at their disposal at the time. The first group of children was called The Rock (Hasela), the same name as the kibbutz when it was founded, before it was changed to Yehiam.

She told us that when the War of Independence ended, they began the actual work of building the kibbutz from the ground up. The siege and the gunfire had almost completely prevented them from building the kibbutz during the war, and after it, they continued with the rock demolition up in Yehiam, in search of water sources.

All of that took almost a year, during which the women and children remained in Kiryat Haim. When you are building a kibbutz, a year is an eternity, Hencha said. For the women who stayed down below in the Kirya, it was the very worst time. Their numbers decreased, every day something else was dismantled and someone else went up to Yehiam, and only they stayed behind. They couldn’t take part in building the kibbutz, and had to make do with hearing reports and an occasional visit.

They were so sick of it, she said. They didn’t even have a kitchen anymore and had to eat at Kibbutz Hahotrim, whose members lived on the adjacent plot of land. It was as if they belonged to that kibbutz, not Yehiam, and they couldn’t have any social interaction of their own there.

The first farmer and plow in Yehiam, protected by an armed guard.

One day in early June, 1949, a taxi arrived at the Kirya, and Eliezer got out of it and ran straight to the chicks that were waiting there to be transported up to Yehiam. But Hencha had had enough; she was angry that everything and everyone else came before the children, even the chickens, as if no one up there in the fortress even remembered that they had children. That was after she had warned them again and again that the women were about to come with the children, and no one had listened to her.

She told Eliezer that the taxi would take the children to Yehiam and his chicks could wait. She snatched the taxi right out from under him. They arrived and announced—we’re here. No one was waiting for them in Yehiam, and nothing was ready. But despite the difficulties, or maybe because of them, Hencha said, the metaplot, the members and the children were very happy that they were all together again after the long, two-and-a-half-year separation that began when the members first went up to Yehiam and the kibbutz was divided into two.

On June 12th, one week after Hencha and the children left Kiryat Haim, the first baby was born on Yehiam itself. That was Ofer, my oldest brother, and my mother said on one of the kibbutz celebrations, or in the fiftieth anniversary film, that everyone was ecstatic. Like in fairy tales, my parents’ little shack seemed to be covered with sweets and goodies. And that was my mother’s most intense experience of togetherness, of how it is possible to fully share a joyful experience.

Filled with happiness, everyone rushed to their house to congratulate them. Ofer was in the Grove group, the kibbutz’s second group.

The first children on the Yehiam kibbutz,

with the Crusader fortress in the background.

When the winter of the children’s first year in Yehiam arrived at the end of 1949, Hencha thought that they might actually have made a serious mistake by taking them there. They couldn’t do anything with the children that winter. The entire kibbutz consisted of a small tin shed that housed the metalworking workshop and another shed where the carpentry workshop was, near the fortress, and the bakery. Everyone lived in small sheds like the shoemaking workshop, and the rain leaked in. You couldn’t wash clothes or dry out shoes. There were no paths or sidewalks, and there was a great deal of mud. The rain didn’t let up for two weeks.

Hencha sometimes told us about the children who were on Yehiam when it first began, and then we’d go back to singing. The evening we learned “The Fisherman’s Daughter” was especially cold, and frightening claps of thunder boomed right above us. We were so deeply immersed in Hencha’s stories of the first children, the harsh winter of the kibbutz’s early days, and the new song we were learning that when we started singing again, the mountain farm blended with the seashore of the fisherman’s daughter. Even after Hencha said goodnight, closed the door and left, we kept on singing the new song we’d just learned, as if it were a prayer:

Across the water a fisherman sailed

Out to the deep sea afar

A gray-eyed young maiden stood watching

And sent out a prayer from her heart

Dear Lord, watch over the ocean

And safeguard the watery ways

For like me, boys and girls stand ashore

And fishermen’s children are they

Into the distance the fisherman vanished

The wind gusted over the water

Back on land in the darkness she stood

All aflutter, the fisherman’s daughter

Dear Lord, watch over the ocean

And safeguard the watery ways

For like me, boys and girls stand ashore

And fishermen’s children are they

Back to land did the fisherman row

From wave to wave with his oar

While she, the incomparable maiden,

Still whispered to sea from shore

Dear Lord, watch over the ocean

And safeguard the watery ways

For like me, boys and girls stand ashore

And fishermen’s children are they

—Lyrics by Binyamin Avigal, music by Miriam Avigal