The song was preceded by a countdown from ten to one, which sometimes began at the quarry junction and sometimes on the Gaaton turn-off. We don’t remember who counted or gave the signal to start the countdown that preceded the song. We weren’t strictly observant about the kibbutz anthem; we didn’t even call it that. If there was a countdown—we sang. If there wasn’t—we continued to sing canons that had no special meaning and went on forever, like, “Hey, a long and winding way, green grass and weeds the live long day. (Second voice): Li lo li lo lay, green grass and weeds the live long day.”

We rode in a GMC back and forth to doctors in Nahariya or to Yehiam’s fields in the Kabri Valley, bouncing along in the hope that the moment we were called to work would be delayed, that the ear-nose-and-throat doctor in the Nahariya clinic would get in the way of a Katyusha rocket before we arrived. We stared at the most mysterious sign of our childhood, which stated: “Please Do Not Throw Out/Cigarettes and Matches in the Pail.” Each of us wracked our brains trying to find an answer to the riddle: How could the sentence be punctuated to avoid contradictions, and could it possibly be suggesting that cigarettes and matches should be thrown outside and not inside the pail? And where was the pail anyway?

The song about Yehiam wasn’t a typical kibbutz song. It didn’t have any particular choreography to go with it, or even a real melody. We kind of recited it, with the “hey hey hey” coming out of nowhere, the way it does in a shepherd’s song. As if whoever wrote it had spent only half a day on it, then had gone back to work in the fields.

Every few years, Yaakov R. was reelected kibbutz secretary, and when he held the office, he gave a speech and made a toast on Rosh Hashana and Passover. His holiday speeches were filled with the mention of crops, as were all the secretaries’ speeches, but they always had an undertone of subtle sarcasm, a sort of second voice like the one in the two-part harmony sung by the choir that was waiting to perform when he finished. “L’Haim, comrades,” the secretary said loudly, raising his eyes from the pages of crop statistics and waving his glass in the air, after he’d described how the bananas had been pounded by a barrage of hailstones and the avocados had been killed by frost. The “L’haim, comrades” was repeated a moment later, after he described the political reversal that left us, the political left, without a hope. And so it went, one blow after another, until he raised his glass again, and in a bitter voice totally unsuited to his holiday toast, repeated the words as if they were the chorus of a lament: “L’haim, comrades.”

Yaakov R.’s sarcasm and irony expressed neither despair nor scorn. They were part of the efforts he made to illuminate the various issues he raised. Yaakov had unique control over his words: He would juggle his arguments in the air, twist them around when they were up there, stop them for a moment in mid-air so the entire kibbutz could stand beneath them and see their other side, then he’d lower them slowly until they landed on the ground.

Since he was a man of action who also knew how to speak more eloquently than anyone else on the kibbutz (his speech wasn’t flowery, but rather almost lyrical), he’d been elected right from the beginning, as if out of nowhere, to lead, to formulate that leadership. He was the one who wrote and read aloud the Djedin scroll, in which the kibbutz members had sworn a blood oath to the place, at night, before they began their climb to Yehiam. Later, he represented the kibbutz in its dealings with the various institutions. During the War of Independence and the siege of Yehiam, he risked life and limb on his many urgent trips to Haifa, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem. He had to find a way to supply Yehiam with everything it didn’t have—land, food, water, ammunition, ways of earning money, cigarettes, and everything necessary to life.

During a fateful kibbutz meeting that took place during the war, on May 15, 1948, when the kibbutz was still split between Kiryat Haim and Yehiam, Yaakov posed the question that had been hovering over Yehiam from the moment it was created on a rocky, isolated hill, and later, when the Partition map placed it inside the borders of the Arab state, and it was engaged in heavy fighting and under ongoing siege:

Is there any chance that we can live in that place, he asked? And who should man the forward post—the kibbutz or the army?

The actual issue under discussion was whether they should stay or leave Yehiam. “Our purpose,” Yaakov said, “is the purpose of every kibbutz, first and foremost to become a cohesive group and prepare ourselves to build a functioning settlement. I asked the powers that be why they don’t take us out of Yehiam. All the answers were only strategic. They do not see us as a settlement, but rather as a position that will defend the Western Galilee. And we cannot take risks. The military knows that only a kibbutz, not army troops alone, can hold the place. They did not tell us what the political considerations of the Kibbutz Ha’artzi are, so I am not sure that the Kibbutz Ha’artzi can go to the institutions with such a demand, but that should be our purpose.”

At the end of that discussion, it was decided that Yaakov and Abush would tell the powers that be, including Yosef Weitz, what had been discussed and what was happening in the kibbutz.

On May 18, 1948, three days after that discussion on the kibbutz, Yosef Weitz wrote in his diary:

The Western Galilee was liberated yesterday, after we took all of Acre, but the problem of Yehiam has yet to be solved. Abush and Yaakov, members of Yehiam, came to see me. The mood there is very dark: Very little food, water is sparse, the place is under fire by snipers almost day and night. All the airdropped items do not reach them, only about a third or a quarter, and the people there ask: What is it all for? If Yehiam is in the Arab state, then it will not be built, and why have people given their lives? And our country’s leaders say over and over again that we will not take more than the United Nations has allocated us. I found it difficult to give them an answer, since I do not share our leaders’ view. We must conquer the entire Western Galilee, for we have shed blood over it. But I agree that the members should leave, and if the commander considers it important militarily, he should send army people there and not rely on settlers. This must be clarified with the Haifa commander.

I am enclosing pages from Yediot, published by the secretariat of the Kibbutz Ha’artzi Hashomer Hatzair, in which there is a description of the attack on Yehiam. The writer is also no longer among the living…

He was referring to the piece written by Rafael, of the Meadow group, about the first attack on Yehiam in January 1948. Rafael was killed two months later, in March, in the Yehiam convoy.

When the war ended, the kibbutz received land in Gaaton Valley and Kabri Valley. At noon, all the members gathered for a meeting with the settlement and Kibbutz Haartzi institutions. The question was, once again, whether to leave the kibbutz, only this time, they discussed the issue from the civilian, agricultural settlement point of view: Should the kibbutz be moved closer to its new lands, or remain where it was, at the foot of the fortress in Djedin-Yehiam, where there was almost no agricultural land?

During the discussion, opposing views, both emotional and practical, were voiced. All the speakers said that so many near and dear ones had sacrificed their lives so the others could live in this place. “How can we leave now?” they asked at the meeting.

In the end, the majority of the members voted in favor of keeping the kibbutz where it was. They didn’t want to leave because of the beauty and wildness of the place, because of the living and the dead, and so the fields remained separate and far away from the kibbutz.

The separation between the fields and the kibbutz that was created in Yehiam was extremely unusual in the structure and agricultural-social-economic concept of kibbutzim. Based on that concept, the link and proximity to the fields were at the very heart of the kibbutz vision of the new, productive, creative man. Work was not a means or a tool for personal profit; it was perceived as an entity in and of itself, and a source of interest and renewal.

The geographical conditions of a mountain kibbutz cut people off from their fields, as if a mountain and a valley of hardships have been placed between them and the work they do.

Though the physical distance between Yehiam and its fields created economic and transportation problems, it did not adversely affect the connection between the members and the fields. As in all kibbutzim, the fields were the focal point of our conscience and everything we reported about ourselves revolved around them. They were the place where records were constantly being broken.

The first paved road to the kibbutz,

a cause for celebration because work could begin.

Nothing interrupted the old-timers’ work, not quotas that were already filled, not holidays or Saturdays, not even children or rest. As if they were in a huge, boundless laboratory of space and time, they immersed themselves in work and saw the fruit of their labors come to life in the growth of the kibbutz.

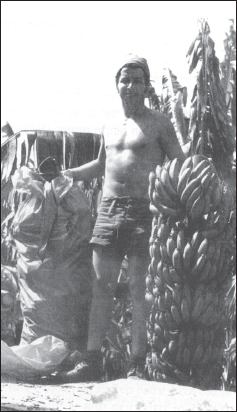

Dov P. said the early years of establishing banana growing as a profitable branch of the kibbutz, from the time he completed his training in 1954, were the happiest years of his life. At night, he waited for morning to come; he had no patience for the night, which interrupted everything, and he would get up and smoke (or smoke and get up) and think about the bananas in the valley, about what each member of his crew would do. Fifteen or eighteen sweaty, drenched members picked thirty tons of bananas in the rain. The record was seventy tons on a single Saturday. They came home dog-tired, but happy. Within four or five years, Yehiam had the largest banana plantation in the area.

The old-timers were happy in their work. Their reward was their work, and vice versa. We all eagerly followed the yield much the way you follow a drama taking place right in front of your eyes. Breaking agricultural work records was the only possible compensation. There were no salaries or other material benefits. The reward was sweeter than anything material; it was sweet, like art, like the joy of doing for its own sake, as its own reward, like a harvest, like an annona or a banana picked straight from the tree.

New records for each season were reported in the newsletter: For example, the season’s largest cluster of bananas (42 kilograms); the average weight of largest clusters to the end of February (24.3 kilograms).

Harvesting bananas.

New inventions, improvements and innovations in agriculture were most highly praised, since they combined several greatly valued principles: creativity, productivity, and industriousness. Zvi Gershon, along with Yoskeh, invented weapons during the siege. (They made mines and bombs with a pliers, a screwdriver and a hammer. With the additional help of a hand drill, they produced dozens of explosive devices that they spread along the fences, and land mines that they buried on the roads leading to Yehiam.) After the war, Zvi Gershon continued to devise agricultural innovations that increased production. For example, he discovered that by dragging four corn seeders hooked up to the back of a tractor, seeding capacity could be doubled. The newsletter said that people flocked from all the agricultural settlements in the area to see the innovation and copy it for themselves.

Thanks to the hybridization carried out by Yair Argaman in the orchards, the entire country’s production record for miniature fruit trees was doubled. “Two and a half years after he planted the miniature orchard, we were producing two tons of fruit per dunam7 of land, which is double the normal crop in Israel for trees that age. A crop that size in this kind of orchard is a national record.”

The newsletter said that scientists, instructors and fruit growers from the four corners of the country came to see that achievement with their own eyes.

Yaakov R. and Yehuda Harari thought about work all the time, even when the working day was over. They thought about it as they walked, hands clasped behind their backs, as if their bodies had twisted physically into questions and thoughts, and now they were thinking back and forth, plowing their thoughts.

Even in the children’s houses, when they came for fifteen minutes to tell us bedtime stories before we went to sleep, if they had an idea, they would pace in the corridor, or even in the room itself, which was only about four meters long. They would pace, stop, turn, then start pacing again. They thought about work, became immersed in their thoughts about it, contemplated various ideas, problems and solutions.

Yaakov R. was the most eloquent speaker on the kibbutz. He didn’t use flowery words, but rather words of action, of persuasion. However, since he was a man of work, he had an occasional attack of hatred toward his own powers of persuasion and refused to speak. And then, like the tug-of-war game played on the Shavuot holiday, the entire kibbutz moved to the other side of the rope and fought Yaakov to make him speak. That’s how it was from the beginning, at the kibbutz meeting on May 20, 1947, which discussed the road-paving holiday. The kibbutz was still split, and the members up in Yehiam wanted to celebrate a great holiday—the paving of a section of the road to Yehiam. The following was said at the meeting:

“We’ve come up against the problem of the speech to be given at the celebration. The fact that Yaakov is going away for a seminar doesn’t change anything. He can come back for two days to be at the party. Yaakov told the secretariat that he was opposed, and now he has to convince the kibbutz.”

Yaakov stood up at the meeting and said:

“I cannot say anything at that celebration because I have nothing to say. Giving a speech is, in some ways, like art. Just as a person cannot write a poem simply because someone has decided that he must, so it is that I cannot give a speech at this celebration.”

The decision: To compel Yaakov to speak.

In favor—20. Against—5.

The magic of Yaakov’s speeches did not carry over to his writing; nor was he one of the people on the kibbutz who wrote manifestoes, aspired to be a Knesset member or anything else that would utilize his skills. His art lay in his ability to formulate the relationship with the community; his art was bound up with action. When he spoke about something, we could see the various sides of yes and no as if they were the sides of a cube. He once said to us:

There was only a superficial understanding of the individual-collective dichotomy. The idea was actually that the individual was very important, and it was believed that the more devoted the individual was and the more he did for the community, the more he would develop.

That was the philosophy, and we accepted it totally. There were always some members who did not contribute very much to the collective—we, who contributed, felt much happier, much more complete, much more satisfied than they did. And to a great extent, we were. They were bitter, and we felt that we were building a world. That is to say, it was not a matter of the individual sacrificing for the collective, but rather it was a matter of the individual developing through the collective.

There can be no doubt that this perception has not stood the test of reality, the test of time, and today, it is anachronistic. We must not return to it.

He always contradicted what he’d said, or blunted it, as if he’d packed his perception into a suitcase, and now others had to come along and offer their merchandise. He needed other proposals in order to practice his powers of persuasion.

Yaakov’s words caused us to go back and forth from thought to reality. When they hit their target, they were like the agricultural innovations—setting new records of reality—or like Ari’s matchstick models.

Ari had a special status. He wasn’t one of the old-timers; he wasn’t an original core group member, nor had he been added to one later. He was born in the kibbutz, a child in Grove, the kibbutz’s second group, and our groupmate Zohar’s older brother. Since he was twelve the newsletter had been reporting on his handiwork the way it reported on the orchard and banana crops. Ari knew how to build anything with matchsticks. The entire kibbutz eagerly followed the new records he set, which he himself broke every year. The new model was exhibited on the kibbutz holiday. In 1963, after the seventeenth one, the newsletter reported:

Without any doubt, Ari’s matchstick creations—the Eiffel Tower, the railroad train, the ship bridge—were the greatest attraction. In order to give an idea of the amount of work he invested in them, suffice it to say that the ship was made of 37,280 matches glued together, which is almost 980 boxes.

Later on, Ari made exact models of the kibbutz houses and the silo.

When we, the kibbutz members, stood in front of Ari’s scale models, which were displayed on tables, and leaned toward them to see every detail better, we were overwhelmed by the sheer number of them. Sometimes forgetting that they were only models, we entered and walked around in them in our minds, and when we remembered that we had to return to reality—we suddenly froze in place with fear. For a moment, everything was topsy-turvy: We were afraid that the kibbutz itself was only a scale model of something much larger, whose creation had snagged in the middle, and that in fact, all our work was in vain, no one was walking behind us to expand the kibbutz enterprise, and what we heard was the sound of our own work shoes clacking on the stone sidewalk. We were afraid that our kibbutzim, like Ari’s scale models, like buildings we’d constructed with temporary beams, were only decoration, the physical embodiment of Yaakov R.’s arguments, an image. As if all the kibbutzim were meant from the beginning to be only the setting for puppets that had escaped from a puppet show and were wandering everywhere on the kibbutz, in the cow barn and the animal pens.

Ari’s models filled us with a strange intoxication, just as Yaakov’s speeches did, as if both were ladders on which we climbed from reality to the rarified air of the loftiest peaks where records were so phenomenal that they verged on fantasy, and for a moment, we were able to live inside the tower of the dream of justice, equality and truth that we had built in the air.